Abstract

BACKGROUND

The objective of this clinical trial was to assess the effects of probiotic soy milk and soy milk on anthropometric measures and blood pressure (BP) in type 2 diabetic (T2D) patients.

METHODS

A total of 40 patients with T2D, 35-68 years old, were assigned to two groups in this randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial. The patients in the intervention group consumed 200 ml/day of probiotic soy milk containing Lactobacillus planetarium A7 and those in control group consumed 200 ml/day of soy milk for 8 weeks. Anthropometric and BP measurements were performed according to standard protocols. For detecting within-group differences paired-sample t-tests was used and analysis of covariance was used for determining any differences between two groups. (The trial has been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, identifier: IRCT: IRCT201405265062N8).

RESULTS

In this study, we failed to find any significant changes between probiotic soy milk and soy milk in term of body mass index (26.65 ± 0.68 vs. 26.33 ± 0.74, P = 0.300) and waist to hip ratio (1.49 ± 0.08 vs. 1.54 ± 0.1, P = 0.170). Although soy milk did not have any effect on BP, probiotic soymilk significantly decreased systolic (14.7 ± 0.48 vs. 13.05 ± 0.16, P = 0.001) and diastolic BP (10 ± 0.7 vs. 9.1 ± 1, P = 0.031).

CONCLUSION

In our study, probiotic soy milk in comparing with soy milk did not have any beneficial effects on anthropometric measures in these patients. We need more clinical trial for confirming the effect of probiotic foods on anthropometric measure in diabetic patients. However, probiotic soy milk decreased systolic and diastolic BP significantly.

Keywords: Probiotics, Obesity, Diabetes Mellitus, Soy Milk, Blood Pressure

Introduction

The proportion of individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) has increased rapidly in worldwide.1 Moderate weight reduction in obese patients with T2D causes a decrease in insulin resistance, glycemic parameters, and diabetic complications.2 Thus, anti-obesity agents may be useful as treatment for obese patients with diabetes.

Recent research has documented a significant impact of gut microbiota on body weight.3 Intestinal microbiota has been suggested to impact energy balance in animals and humans4 by contributing to energy metabolism from components of the diet and playing a role in energy storing and expending.4,5 Probiotics are of interest because it is shown that can alter the composition of the gut bacterial community and differentiate food intake and appetite.6,7 Dietary non-digestible carbohydrates can be fermented by probiotics and resulting in the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate and butyrate. SCFAs play a role in energy metabolism and adipose tissue expansion.7

In human and animal studies co-administration of probiotics with other interventions like herbal drugs or weight reduction diet could reduce anthropometric measures,8-11 and to our knowledge no reports are available indicating the effects of probiotic supplements alone especially this strain of probiotics. Furthermore, previous studies have mostly been done in animal models and limited data of the effects on humans are available.

Obesity and insulin resistance increase blood pressure (BP) in diabetic patients. Previous human studies have found some beneficial effects of Lactobacillus species in reducing BP in patients with hypertension.12 Scientists believe that probiotics can reduce BP by decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and intestinal permeability so resulting in splanchnic vasodilation and deceasing BP in patients with hypertension.13 To our knowledge, there is not any study about the effect of Lactobacillus planetarium A7 on BP among diabetic patients. New evidence proposed probiotics can ferment soy phytoestrogen and increase the amount of SCFA produced by probiotics, therefore; soy foods are able to strengthen the useful effect of these bacteria.14,15 Hence in this study, we fortified soy milk with L. planetarium A7 and assessed the effect of daily consumption of probiotic soy milk on anthropometrics measure and BP in patients with T2D.

Materials and Methods

This randomized double-blinded parallel-group controlled clinical trial was carried out in Isfahan, Iran. Subjects were recruited from Endocrine and Metabolism Research Center, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, during their annual health assessment. Our subjects were T2D patients with fasting blood glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, blood sugar (2 h postprandial sugar) ≥ 200, aged from 25 to 65 years, and having diabetes for more than 1-year. Subjects were excluded if they have a history of inflammatory bowel disease, infection, liver disease, rheumatoid arthritis, smoking, alcoholism, recent antibiotic therapy, and daily intake of multivitamin and mineral. Each participant was assigned an order number and was randomly assigned by permuted blocks randomization of size two to one of two 8-week intervention groups. The allocation sequence was concealed from the researchers who enrolled and assessed participants. Allocation concealment will be ensured, as the service will not release the randomization code until the end of trial, which takes place after all baseline measurements have been completed and outcomes were measured. The conventional or probiotic soy milk were provided for the participants every 3 days. Each day, the subjects received, in a double-blinded fashion, probiotic soymilk or soy milk to supplement their usual diet. The probiotic soy milk and soy milk were identically packed and coded by the producer to guarantee blinding. The 8-weeks probiotic intervention consisted 200 ml soy milk/day. All subjects were included in a 2-weeks run-in period during this time they had to stop taking any probiotic food or probiotic supplements. A total of 48 patients (22 males and 26 females) with T2D and age range 35-68 years old were recruited into the study they were randomly assigned to receive either probiotic soy milk (n = 24, i.e., 12 males and 12 females) as intervention group or the soy milk (n = 24, i.e. 10 males and 14 females) as placebo group for 8 weeks. All subjects had to have stable dietary habit, physical activity (PA), and medication during intervention and consume milk instead of yogurt and any other fermented dairy products. Compliance with the soymilk and dairy product consumption was monitored by the use of 24 h diet recall completed every 2 weeks throughout the study. Information on PA levels and micro and macronutrients intakes were gathered at beginning of study and every 2 weeks throughout the study by International PA Questionnaires 16 and a 24 h diet recall respectively. Subjects who intended to change their dietary habits, PA, body weight, and consume fermented product except probiotic soymilk during the intervention period were excluded from the study. The Ethical Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences approved the study, and informed written consent was taken from all participants. (The trial has been registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials, identifier: IRCT: IRCT201405265062N8 available at: http://www.irct.ir).

The probiotic soy milks were enriched with L. plantarum A7. Conventional soy milk and probiotic soy milk were produced by Isfahan Soy Milk Company every 3 days and distributed to the participants. At the time of production and after 3 days refrigerating at 4 °C probiotic soy milks were sampled and microbiologically analyzed every 2 weeks. We used MRS Broth (MRS agar: Merck, Darmstadt, Germany and bile: Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., Reyde, USA) and pour plate method for counting L. plantarum A7. Microbiological analyses of probiotic soy milk approved the probiotic soymilk had that the average colony counts of L. plantarum A7 on day 1 and day 3 about 2 × 107 therefore; bacteria indicated a steady survival rate in soy milk during 3 days storage time.

Weight was recorded by digital scale (Seca, Germany) with an accuracy of 100 g and standing height was recorded by non-stretchable tape (Seca, Germany) with an accuracy of 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was obtained by dividing weight by the square of height. Waist and hip circumference was measured using a flexible measuring tape. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the lower ribs and the iliac crest. Hip circumference was measured horizontal at the largest circumference of the hip. BP was measured using mercury sphygmomanometer after the participants had been seated quietly for 5 min and the right arm supported at heart level. A cuff bladder encircling at least 80% of the arm was used to ensure accuracy. Two readings were obtained with a 1-min interval. A third BP was measured if more than 5 mmHg difference in SBP between the two readings was noted, and the mean of the two closest was taken as the valid BP.17

To ensure the normal distribution of variables, histogram and Kolmogrove-Smirnov test were applied. For non-normally distributed variables, log-transformation was applied. Means ± standard error of means for general characteristics of the study participants were reported. Data on dietary intakes were compared by paired t-test and independent samples test. For comparing PA and sex in two groups we used chi-square test and the duration of disease and age were compared using independent t-test. For detecting within-group differences in anthropometric measures paired-sample t-tests were used and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used for determining any differences between two groups and was adjusted by baseline values and confounding factors. Possible confounding factors were calorie and carbohydrate intake and baseline values. P < 0.050 was defined to be statistical significance and all experimental data were analysis by using the SPSS for Windows (version 20, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

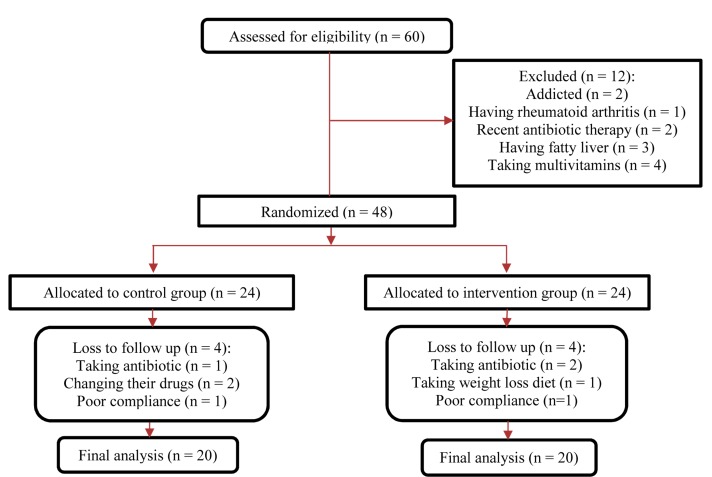

This study was carried out from November 2013 to February 2014, and 48 diabetic patients participated in this study. Among individuals in the placebo group, 4 patients (need for antibiotic treatment, n = 1; changing drug, n = 2; poor compliance, n = 1) were excluded. Four patients in probiotic soy milk group were excluded (need for antibiotic treatment, n = 2; changing diet, n = 1; poor compliance, n = 1). Finally, 40 subjects (soy milk, n = 20; probiotic soy milk, n = 20) completed the trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summary of patient flow

No serious adverse reactions were reported following the consumption of multispecies probiotic supplements in patients throughout the study. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants in the two groups. The two groups were similar in their initial characteristics and there was not any significant difference in the number of male and female (P = 0.750) and PA levels (P = 0.280) in both groups. At the beginning of the study, no significant differences were found between the two groups in terms of dietary intakes except for carbohydrate (P < 0.001), furthermore; statistically significant difference was found between the two groups for dietary intakes of energy and carbohydrate at throughout of study. Comparing the dietary intakes at the beginning of study and throughout the study separately in each group, showed any significant differences (Table 2). There were not any significant differences in terms of BMI (P = 0.920) and waist to hip ratio (WHR) (P = 0.610) at the beginning of study between two groups, but after intervention in probiotic soy milk a significant within group reduction was found in BMI (P < 0.010) and WHR (P < 0.050). But we did not find a significant difference between two groups after adjusting by baseline values, confounding factors with ANCOVA (Table 3). There were any significant difference for systolic (P = 0.310) and diastolic BP (P = 0.280) in both group at the beginning of study. However, probiotic soy milk significantly reduced systolic (P < 0.001) and diastolic BP (P < 0.050) even after adjusting by cofounding factors and baseline values with ANCOVA (P < 0.001), but systolic and diastolic BP didn’t show any significant changes in soy milk group (P = 0.120 and 0.670, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| Variables | Intervention (n = 20) | Placebo (n = 20) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year)* | 56.90 ± 1.81 | 53.60 ± 1.60 | 0.182*** |

| The duration of disease* | 8.70 ± 2.10 | 6.90 ± 4.90 | 0.467*** |

| Height (cm)* | 162.95 ± 1.47 | 163.60 ± 1.35 | 0.747*** |

| Sex (F/M) (%)** | 11/9 (55/45) | 10/10(50/50) | 0.752€ |

| PA (low/moderate) (%)** | 16/4(80/20) | 13/7** (65/35) | 0.288€ |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 26.68 ± 0.71 | 26.58 ± 0.73 | 0.925*** |

| WHR* | 1.52 ± 0.09 | 1.59 ± 0.11 | 0.610*** |

| Weight (kg)* | 70.84 ± 2.41 | 71.61 ± 2.55 | 0.828*** |

| Systolic BP* | 14.70 ± 0.48 | 14.30 ± 0.71 | 0.310*** |

| Diastolic BP* | 10.00 ± 0.70 | 10.70 ± 0.90 | 0.281*** |

Data are based on mean ± standard error;

Percent, or frequency;

Obtained from independent t-test;

Obtained from chi-square test;

BP: Blood pressure; PA: Physical activity; BMI: Body mass index; WHR: Waist to hip ratio

Table 2.

Reported nutrient intake of participants on probiotic soy milk and soy milk at baseline and throughout the study

| Variables | Intervention | Placebo | P** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | Throughout the study€ | P* | Before | Throughout the study | P* | ||

| Carbohydrate (g/day) | 275.50 ± 5.53 | 269.00 ± 5.01 | 0.349 | 309.70 ± 6.54 | 307.72 ± 5.75 | 0.663 | < 0.001 |

| Protein (g/day) | 61.60 ± 1.80 | 62.42 ± 1.33 | 0.457 | 62.22 ± 1.19 | 63.13 ± 0.98 | 0.419 | 0.777 |

| Fat (g/day) | 90.55 ± 1.92 | 90.60 ± 1.95 | 0.980 | 92.89 ± 2.59 | 92.23 ± 2.18 | 0.699 | 0.473 |

| Calorie (Kcal/day) | 2105.85 ± 33.48 | 2095.19 ± 20.09 | 0.790 | 2173.45 ± 32.11 | 2182.65 ± 30.95 | 0.727 | 0.023 |

| Calcium (mg/day) | 1147.00 ± 10.01 | 1168.63 ± 9.25 | 0.359 | 1089.06 ± 11.14 | 1127.61 ± 9.21 | 0.582 | 0.331 |

| Magnesium (mg/day) | 340.75 ± 7.32 | 319.32 ± 5.10 | 0.406 | 312.16 ± 4.19 | 329.67 ± 8.30 | 0.214 | 0.521 |

| Potassium (g/day) | 4.20 ± 0.47 | 4.10 ± 0.22 | 0.361 | 4.38 ± 0.54 | 4.40 ± 0.36 | 0.601 | 0.311 |

Data are means ± standard error;

Obtained from a paired t-test;

Obtained from independent sample t-test for the comparison of dietary intakes throughout the study between the two groups;

The means of all 24 h food recall that was gathered every 2 weeks at throughout study

Table 3.

Anthropometrics measures at baseline and after 8 weeks of study

| Variables | Intervention (n = 20) | Placebo (n = 20) | P** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | P* | Before | After | P* | ||

| Weight (kg) | 70.84 ± 2.41 | 70.40 ± 2.33 | 0.018 | 71.61 ± 2.55 | 71.21 ± 2.56 | < 0.001 | 0.964 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.68 ± 0.71 | 26.65 ± 0.68 | 0.003 | 26.58 ± 0.73 | 26.33 ± 0.74 | < 0.001 | 0.309 |

| WHR | 1.52 ± 0.09 | 1.49 ± 0.08 | 0.019 | 1.59 ± 0.11 | 1.54 ± 0.10 | 0.070 | 0.175 |

| Systolic BP | 14.70 ± 0.48 | 13.05 ± 0.16 | 0.001 | 14.30 ± 0.71 | 14.40 ± 0.23 | 0.120 | 0.002 |

| Diastolic BP | 10.00 ± 0.70 | 9.10 ± 1.00 | 0.031 | 10.70 ± 0.90 | 10.50 ± 0.12 | 0.670 | < 0.001 |

Data are means ± standard error;

Obtained from a paired t test;

Obtained from ANCOVA after adjusted with calorie and carbohydrate intake and baseline values;

BMI: Body mass index; WHR: Waist to hip ratio; BP: Blood pressure

Discussion

Our study revealed that the consumption of probiotics soy milk and soy milk for 8 weeks among patients with T2D decreased BP and anthropometric measures, however; we did not find any significant differences between two groups in term of anthropometric measures after adjusting with covariates.

Recently, researchers have found that polyphenols played an important role in the treatment of obesity, through a mechanism involving the anti-oxidative function and scavenging of free radicals.18 Polyphenols promote the transport of unsaturated fatty acids (FA), which increases the gene expression of enzymes that related to thermogenesis, adipogenesis or FA oxidation and causing weight loss.19 In one cross-sectional study by Wang et al. indicated that people with low frequency of soybean intake had significantly higher risk to overweight and obesity.20 Hu et al. reported that soy fiber had favorable effects on anthropometric measures, and fasting low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults.21 Keshavarz et al. showed that soy milk can play an important role in reducing waist circumference among over weight and obese patients.22 Similar our results were shown in one study by Kadooka et al.23 They indicated Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in fermented milk did not reduce abdominal obesity in adult, after 24 weeks, mean weight loss did not show significant difference between the probiotic and placebo groups; however, in one study by Sharafedtinov et al., the probiotic L. plantarum TENSIA significantly reduced BMI in the probiotic cheese group versus the control cheese group.11 Difference in findings of these studies can be described by distinction between probiotic strain and dosage or differences between participants.24 In our study, probiotic soy milk significantly reduced anthropometric measures in compared with the beginning of study but there were not any differences between two groups after adjusting by covariates. Therefore, we fail to show significant reduction in term of anthropometric measures by soy milk fortified with L. planetarium A7. It should note that the properties of different probiotic species vary and can be strain-specific. Therefore, the effects of one probiotic strain should not be generalized to others without confirmation in separate studies. It was for the first time that the effect of L. planetarium A7 was studied on human and it is possible that this strain of probiotics does not have any effect on anthropometric measures.

Our study revealed that probiotic soy milk can reduce BP in diabetic patients. Numerous randomized clinical trials of Lactobacillus helveticus have indicated that supplementation with this species has antihypertensive effects in human.25-27 It is not surprising that other studies with different probiotic strains and species found different results, because the effect of probiotic bacteria is highly strain specific.28 Although other studies indicated that soy milk reduces BP,29,30 but in our study, soy milk did not reduce BP in diabetic patients.

Short duration of intervention, the absence of control group that consumed no soy milk, and 24 h diet recall instead of 3-day food record were our limitations in this study that must be considered while interpreting the results. Therefore for confirming the positive effects of probiotics soy milk on the anthropometric measures among diabetes patients more investigations with longer duration and control group without soy milk should be done.

Studies have been published before suggested that probiotics reduced anthropometric measures in humans. However, those studies used another species of probiotics and enrolled participants with higher BMI in comparing with our participants. In our randomized controlled trial, L. planetarium A7 could not reduce anthropometric measures among diabetic patients, and like other studies we indicated that this kind of probiotics can reduce BP.

Conclusion

As the intervention was implemented for both sexes and all ages among diabetic patients, results indicate that diabetic patients may benefit from using probiotic soy milk for decreasing BP. However, we need more studies for determine the effect of this strain of probiotic on anthropometric measures.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Isfahan soy milk company that provided soy milk products for the present study. We would like to express our special thanks to all patients that participate in our study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors have no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morikawa H. American Association of Diabetes Educators, the current DSME (diabetes self-management education) standards. Nihon Rinsho. 2012;70(Suppl 5):617–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bervoets L, Van HK, Kortleven I, Van NC, Hens N, Vael C, et al. Differences in gut microbiota composition between obese and lean children: a cross-sectional study. Gut Pathog. 2013;5(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turnbaugh PJ, Gordon JI. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J Physiol. 2009;587(Pt 17):4153–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delzenne NM, Cani PD. Interaction between obesity and the gut microbiota: relevance in nutrition. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:15–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piche T, des Varannes SB, Sacher-Huvelin S, Holst JJ, Cuber JC, Galmiche JP. Colonic fermentation influences lower esophageal sphincter function in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(4):894–902. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cani PD, Bibiloni R, Knauf C, Waget A, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM, et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 2008;57(6):1470–81. doi: 10.2337/db07-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruijschop RMAJ, Boelrijk AEM, te Giffel MC. Satiety effects of a dairy beverage fermented with propionic acid bacteria. International Dairy Journal. 2008;18(9):945–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park DY, Ahn YT, Park SH, Huh CS, Yoo SR, Yu R, et al. Supplementation of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032 in diet-induced obese mice is associated with gut microbial changes and reduction in obesity. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee SJ, Bose S, Seo JG, Chung WS, Lim CY, Kim H. The effects of co-administration of probiotics with herbal medicine on obesity, metabolic endotoxemia and dysbiosis: a randomized double-blind controlled clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(6):973–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharafedtinov KK, Plotnikova OA, Alexeeva RI, Sentsova TB, Songisepp E, Stsepetova J, et al. Hypocaloric diet supplemented with probiotic cheese improves body mass index and blood pressure indices of obese hypertensive patients--a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Nutr J. 2013;12:138. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jauhiainen T, Ronnback M, Vapaatalo H, Wuolle K, Kautiainen H, Groop PH, et al. Long-term intervention with Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk reduces augmentation index in hypertensive subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(4):424–31. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tandon P, Moncrief K, Madsen K, Arrieta MC, Owen RJ, Bain VG, et al. Effects of probiotic therapy on portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis: a pilot study. Liver Int. 2009;29(7):1110–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zielinska D, Kolozyn-Krajewska D, Goryl A, Motyl I. Predictive modelling of Lactobacillus casei KN291 survival in fermented soy beverage. J Microbiol. 2014;52(2):169–78. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-3045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teh SS, Ahmad R, Wan-Abdullah WN, Liong MT. Enhanced growth of lactobacilli in soymilk upon immobilization on agrowastes. J Food Sci. 2010;75(3):M155–M164. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasheghani-Farahani A, Tahmasbi M, Asheri H, Ashraf H, Nedjat S, Kordi R. The Persian, last 7-day, long form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire: translation and validation study. Asian J Sports Med. 2011;2(2):106–16. doi: 10.5812/asjsm.34781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–52. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin J, Zhang H, Ye J. Traditional chinese medicine in treatment of metabolic syndrome. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2008;8(2):99–111. doi: 10.2174/187153008784534330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuan J, Zheng PY. Probiotics and traditional Chinese medicines for the improvement of obesity: research progress. Chinese Journal of Microecology, 2013;(2):233–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JW, Tang X, Li N, Wu YQ, Li S, Li J, et al. The impact of lipid-metabolizing genetic polymorphisms on body mass index and their interactions with soybean food intake: a study in a Chinese population. Biomed Environ Sci. 2014;27(3):176–85. doi: 10.3967/bes2014.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu X, Gao J, Zhang Q, Fu Y, Li K, Zhu S, et al. Soy fiber improves weight loss and lipid profile in overweight and obese adults: a randomized controlled trial. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57(12):2147–54. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshavarz SA, Nourieh Z, Attar MJ, Azadbakht L. Effect of Soymilk Consumption on Waist Circumference and Cardiovascular Risks among Overweight and Obese Female Adults. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(11):798–805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadooka Y, Sato M, Ogawa A, Miyoshi M, Uenishi H, Ogawa H, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in fermented milk on abdominal adiposity in adults in a randomised controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2013;110(9):1696–703. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyle RJ, Robins-Browne RM, Tang ML. Probiotic use in clinical practice: what are the risks? Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1256–64. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hata Y, Yamamoto M, Ohni M, Nakajima K, Nakamura Y, Takano T. A placebo-controlled study of the effect of sour milk on blood pressure in hypertensive subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;64(5):767–71. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.5.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauhiainen T, Vapaatalo H, Poussa T, Kyronpalo S, Rasmussen M, Korpela R. Lactobacillus helveticus fermented milk lowers blood pressure in hypertensive subjects in 24-h ambulatory blood pressure measurement. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(12 Pt 1):1600–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zarrati M, Shidfar F, Nourijelyani K, Mofid V, Hossein zadeh-Attar MJ, Bidad K, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium BB12, and Lactobacillus casei DN001 modulate gene expression of subset specific transcription factors and cytokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of obese and overweight people. Biofactors. 2013;39(6):633–43. doi: 10.1002/biof.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahboobi S, Iraj B, Maghsoudi Z, Feizi A, Ghiasvand R, Askari G, et al. The effects of probiotic supplementation on markers of blood lipids, and blood pressure in patients with prediabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5(10):1239–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miraghajani MS, Najafabadi MM, Surkan PJ, Esmaillzadeh A, Mirlohi M, Azadbakht L. Soy milk consumption and blood pressure among type 2 diabetic patients with nephropathy. J Ren Nutr. 2013;23(4):277–82. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azadbakht L, Nurbakhsh S. Effect of soy drink replacement in a weight reducing diet on anthropometric values and blood pressure among overweight and obese female youths. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2011;20(3):383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]