Abstract

Context

Pediatric palliative care randomized controlled trials (PPC-RCTs) are uncommon.

Objectives

To evaluate the feasibility of conducting a PPC-RCT in pediatric cancer patients.

Methods

This was a cohort study embedded in the Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) Study (NCT01838564). This multicenter PPC-RCT evaluated an electronic patient-reported-outcomes system. Children ≥2-years-old, with advanced cancer, and potentially eligible for the study were included. Outcomes included: pre-inclusion attrition (patients not approached, refusals); post-inclusion attrition (drop-out, elimination, death, and intermittent attrition (IA; missing surveys) over 9 months of follow-up); child/teenager self-report rates; and, reasons to enroll/participate.

Results

Over five years, of the 339 identified patients, 231 were eligible (in 22 we could not verify eligibility); 84 eligible patients were not approached and 43 declined participation. Patients not approached were more likely to die or have brain tumors. We enrolled 104 patients. Average enrollment rate was one patient/site/month; shortening follow-up from nine to three months (with optional re-enrollment) increased recruitment by 20%. Eighty-seven patients completed the study (24 died) and 17 dropped out. Median intermittent attrition was 41% in the first 20 weeks of follow-up, and over 60% in the eight weeks preceding death. Child/teenager self-report was 94%. Helping others, low burden procedures, incentives, and staff attitude were frequent reasons to enroll/ participate.

Conclusion

A PPC-RCT in children with advanced cancer was feasible, post-inclusion retention adequate; many families participated for altruistic reasons. Strategies that may further PPC-RCT feasibility include: increasing target population through large multicenter studies, approaching sicker patients, preventing exclusion of certain patient groups, and improving data collection at end of life.

Keywords: pediatrics, pediatric oncology, supportive care, feasibility, attrition, end-of-life care, patient-reported outcomes, randomized controlled trial, palliative care

Introduction

Although the need for high quality intervention research in pediatric palliative care has long been recognized as a priority (1-4), such studies are uncommon and difficult to accomplish (5). Research in children with advanced illness entails dealing with small and heterogeneous populations, highly sensitive topics, and complex outcomes measurement (i.e., developmentally adapted and inclusive of parents) (6, 7). These requirements add to the barriers to palliative care investigations (8).

Systematic reviews have identified accrual, patient retention, and valid outcome measurement as the leading obstacles to adult palliative care randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (9-11). Reasons for the low enrollment rates include patients being either too overwhelmed or dying before accrual, and caregivers’ or clinicians’ beliefs that the ill patient cannot withstand participation or that study procedures are too burdensome or not worth the patient's time (12-15). Furthermore, palliative care studies inevitably have high attrition rates (8). Participation deterrents include death, illness progression, and drop-out or intermittent missing data because of patient or family request, change in treatment facility or clinician, or overwhelmed caregivers (14, 16-18). Despite these challenges, a recent systematic review found that participation in end-of-life care research is a positive experience, with most participants reporting direct benefits or comfort, and viewing participation as a means to contribute to care improvement (19).

Pediatric palliative care (PPC) RCTs are scarce. Four studies were identified; three evaluated telemedicine interventions (5, 20, 21), two of which were not completed because of low accrual, and the remaining one assessed an advanced care planning intervention (22). Even though RCTs are needed to increase the field's evidence base, guidance on how to effectively conduct them is scant (23).

We sought to assess the feasibility of conducting a PPC RCT in children with cancer that advanced beyond initial treatment. The Pediatric QUality of life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) Study evaluated the effect of an electronic patient- reported outcomes system on child distress(24). Feasibility was concurrently appraised. We describe the different sources of data loss, or attrition, from the moment patients were identified through the end of follow-up, and families’ views on participation at study entry and exit.

Methods

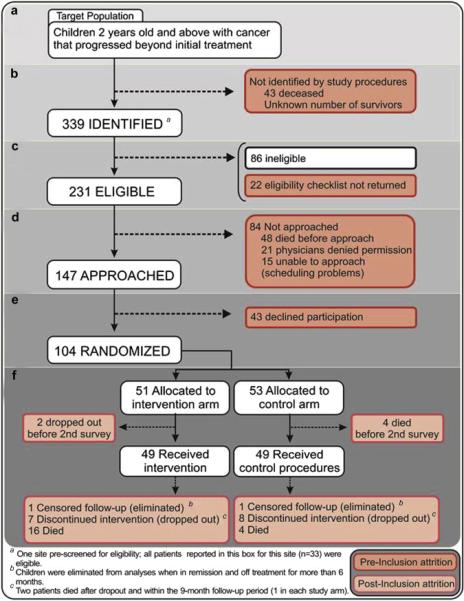

The PediQUEST Study was a pilot parallel 1:1 RCT conducted at three large U.S. pediatric cancer centers from December 2004 to December 2009. Methods described below pertain to the feasibility study. RCT methods have been described elsewhere (24) and are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Methods used in the Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) Study – RCT Methods (adapted from Wolfe J et al.24). 1The PediQUEST-Survey (PQ-Survey) is an electronic survey that includes the adapted PediQUEST-Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (PQ-MSAS, which evaluates symptom burden) and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL4.0™, which evaluates quality of life).

Design and Participants

This was a cohort study embedded in the PediQUEST pilot RCT. All children identified as potentially eligible for the PediQUEST Study were included regardless of their participation status. The study was approved by the institutional review boards (IRBs) of participating sites.

Study Procedures

Attrition was defined following Howard (25) as “any data loss occurring during the study” and classified as: 1) pre-inclusion attrition, i.e., data loss before randomization, including patients missed by study procedures, identified but not approached, and those who declined enrollment; and 2) post-inclusion attrition, or after randomization data loss, consisting of drop-out, elimination, death, and intermittent attrition (missing PediQUEST survey [PQ-survey] opportunities during follow-up).

To study pre-inclusion attrition, we: 1) screened all cancer deaths that occurred during the study period to detect patients who would have met eligibility criteria but were not identified through study procedures; 2) abstracted demographic and illness characteristics from medical records of all eligible patients; 3) tracked time from identification to enrollment/refusal; and 4) explored reasons for enrolling or declining through a paper-and-pencil “Consent Survey” administered on site or sent by mail to parents/legal guardians of all approached subjects immediately following initial contact. This 44-item survey, adapted from Tait et al. (26), assessed perceived appropriateness of the child's inclusion, decisional effectiveness, privacy and time needed to make the decision, perceived study burden, and parent's trust in the health care system and sense of altruism. Non-consenters received an abridged version. Consent documentation was waived. Families received a small non-monetary incentive.

Post-inclusion attrition is reported for nine months, the original proposed follow-up. Specifically, we: 1) tracked drop-out, elimination (patients off treatment and in remission for six months), and death among enrollees; 2) explored reasons for staying (or not) in the study and satisfaction with participation using a paper-and-pencil 28-item “Participation Survey”, adapted from Janson et al. (27), and administered upon study completion, drop-out, or at least four months after the child's death; 3) calculated intermittent attrition (IA) as number of PQ-surveys not administered over total number of eligible PQ-survey administration opportunities (eligible PQ opportunities) overall and per month, and explored reasons for intermittent participation. Eligible PQ opportunities were identified through administrative records and defined, based on study procedures (Fig. 1), as any scheduled clinic appointment with the oncologist, or any day during an admission, that was at least one week apart from the prior PQ-survey or eligible PQ opportunity. Patients who had no appointment or admission for over one month were assigned a monthly eligible PQ opportunity. Research staff recorded reasons for not administering a survey; an eligible PQ opportunity that was inadvertently missed was classified as a “missed opportunity.” To further inform the feasibility of routinely collecting patient-reported outcomes, we tracked respondent (patient/parent), completion time, and survey completeness.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics including frequencies and means or medians were used to summarize pre- and post-inclusion attrition. We explored whether gender, study arm, type of tumor, age, and survival were associated with attrition. We compared approached to not approached subjects and enrolled to non-enrolled subjects for pre-inclusion attrition; and dropout subjects to those who completed the study for post-inclusion attrition. Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum or t-test for numerical variables. We explored the relationship of IA with the covariates mentioned above, location (clinic visit, inpatient, home), and dropout status through univariate analysis. We also examined monthly variation of IA, aiming to identify an optimal follow-up time. We defined 40% IA as a recommended threshold following Judson et al. (28). Finally, we explored IA at end of life by analyzing eligible PQ opportunities during the last 12 weeks of life. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Reasons to enroll and remain in the study were analyzed using qualitative methodology. Specifically, quantitative and qualitative data from the consent and participation surveys were combined into seldom convergence coding matrixes and used to conduct thematic coding and content analysis (29).

Results

Pre-Inclusion Attrition

Using methods described in Fig. 1, we identified a total of 339 potentially eligible subjects over the five years the study was open (Fig. 2, Level B). Forty-three additional children who would have been eligible were identified through review of cancer deaths, representing the lower boundary for those missed by study procedures. Sixty-eight percent of identified patients were eligible; in 6%, we could not verify eligibility (Level C). Sensitive to patients’ clinical status, we agreed with primary providers on the timing to invite a family to participate in the study. Of the 231 eligible patients, 64% were approached (Level D). The most frequent reason for not making contact with families was that the child had died after being identified, but prior to contact. Seventy-one percent of those approached enrolled in the study (Level E) at an average rate of one patient per site per month. Median time from eligibility to enrollment was 39 (interquartile range [IQR] 20-90) days. After 4.5 years of accrual, enrollment was closed at 104 patients before reaching the target sample of 120 because we concluded that the cost of enrolling 16 additional patients outweighed the information these patients would contribute. The reduction in proposed follow-up from nine to three months with re-enrollment opportunities, as explained in Fig. 1, significantly increased recruitment rates from 58% to 77% (P=0.0147). This strategy did not increase the approach rate among patients who were going to die by nine months (after being identified), but their refusal rate, once approached, was lower (nine of 17 and one of 13, respectively).

Fig. 2.

The Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology (PediQUEST) Study flow diagram at nine months of follow-up. The Figure shows the sampling process and disposition at nine months of follow-up. Indicators used to study pre- and post-inclusion attrition are shown. Level A shows the target population; Level B: subjects missed and identified by study procedures; Level C: ineligible and eligible subjects; Level D: not approached and approached subjects; Level E: refused and enrolled; Level F: disposition at nine months of follow-up.

Table 1 shows characteristics of all identified and eligible patients. No significant differences were observed between enrolled and not enrolled patients. Those approached for enrollment were similar to those “not approached” in all but two characteristics: type of cancer and survival. Patients not approached were less likely to have a hematological malignancy and more likely to have brain tumors (P=0.0051), and to die at three or six months after being identified (P<0.0001). Notably, the six-month death incidence of the 21 patients whose provider denied permission to approach was not significantly different to that of those approached (19% and 12%, respectively, P=0.3321). The 43 patients missed by study procedures (Fig. 2, Level B) had a mortality rate that was similar to that of the non-approached (21% and 52% at three and six months), and a larger prevalence of brain tumors (60%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 231 children with advanced cancer identified and eligible for the PediQUEST Randomized Controlled Study, by disposition status.

| Approached for Enrollment (n=147) |

Not approached (n=84) |

p valueb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (n=104) | Not enrolled (n=43) | p valuea | All (n=147) | ||||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||||

| Female | 51 | 49 | 18 | 42 | 0.4276 | 69 | 47 | 29 | 35 | 0.0663 | |

| Non-Hispanic White Race | 92 | 88 | 33 | 77 | 0.0700 | 125 | 85 | 65 | 80 | 0.3533 | |

| Child's age (by groups) | |||||||||||

| 2-4 year-olds | 16 | 15 | 3 | 7 | 19 | 13 | 15 | 18 | |||

| 5-7 year-olds | 15 | 15 | 9 | 21 | 0.5175 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 10 | 0.3734 | |

| 8-12 year-olds | 23 | 22 | 9 | 21 | 32 | 22 | 17 | 20 | |||

| ≥13 year-olds | 50 | 48 | 22 | 51 | 72 | 49 | 44 | 52 | |||

| Diagnosis | |||||||||||

| Hematological malignancies | 36 | 34 | 14 | 33 | 50 | 34 | 18 | 22 | |||

| Brain Tumors | 10 | 10 | 6 | 14 | 0.7436 | 16 | 11 | 22 | 26 | 0.0051 | |

| Solid Tumors | 58 | 56 | 23 | 53 | 81 | 55 | 44 | 52 | |||

| Deaths | |||||||||||

| At 3 months from eligibility | 4 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 0.1231c | 9 | 6 | 30 | 36 | <0.0001 | |

| At 6 months from eligibility | 11 | 11 | 6 | 14 | 0.5774 | 17 | 12 | 46 | 55 | <0.0001 | |

Chi2 tests (unless otherwise indicated) comparing enrolled vs. non-enrolled

Chi2 tests comparing approached vs. non-approached

Fisher's exact test

Reasons to Enroll in or Decline the PediQUEST Study

The consent survey was answered by 95 of 147 (65%) approached patients including 83 of 104 (80%) enrolled subjects and 12 of 43 (28%) non-enrolled; 90% were parents (mostly mothers), 8% patients 18 years old or older, and 2% grandparents. Among those enrolled, respondents and non-respondents were comparable. Non-enrollee response rates varied highly by site (7%, 20%, and 88%), suggesting there were differences in administration strategies. Fig. 3, panel A presents respondents’ answers to selected items and reveals differences in how enrolled and non-enrolled respondents understood the study, and perceived enrollment processes. Enrolled respondents mostly reported that quality of life studies were important, and their child was a good candidate for the study; they enrolled to help other families and give back to the institution. Qualitative analysis identified the following themes behind families’ decisions (Fig. 3, panel B): enrollees reported enrolling because of the desire to “help other cancer patients and their families” (n=43), “improve care” (n=17), and “child's wish to participate” (n=12); whereas non-enrollees most frequently cited that the “study involved too much time or effort” (n=6), and that the “child was not interested” (n=4).

Fig. 3.

Families’ perceptions, values, and reasons to enroll in or decline the PediQUEST Study. Panel A shows perceptions of enrolled (83/104) and non-enrolled (12/43) families regarding study's consent and decision-making processes, as well as values and reasons underlying their participation decision. Non-enrollees responded to an abridged survey version. Given the low non-enrolled response rate, no statistical testing was conducted. Only items with fewer than 10% missing values are graphed. Panel B presents reasons to enroll or not in the PediQUEST Study as reported in open-ended questions (or quantitative items in the five surveys where comments were not provided). Over a third of respondents provided more than one reason. Representative quotes from enrolled and non-enrolled respondents are shown.

Post-Inclusion Attrition

Median duration of participation was 4.8 (IQR 2.7-9.0) months. Over nine months, 87 of 104 patients completed study requirements; of these, two were eliminated and 24 died. Fig. 2, Level F shows censoring across study arms and Fig. 4, the number of subjects at each time point by type of censoring. The higher death incidence in the intervention arm (Fig. 2-F) was unforeseen and likely related to chance (24).

Fig. 4.

Disposition of patients enrolled in the PediQUEST Study over nine months of follow-up and feasibility of longitudinal assessment of electronic patient-reported outcomes. Line graph (top): number of study subjects available per week after censoring for: death (red line); death, drop-out, and elimination (green line); death, drop-out, elimination, and administrative censoring (black line). Area graph (bottom): number of eligible PQ opportunities at each time point and the number that resulted in: an administered survey (green area), a not administered survey (purple) where reason for no administration was known; or a missed opportunity (light purple), i.e. opportunities that were inadvertently missed by research staff.

Seventeen patients dropped out; their median follow-up was 3.8 (IQR 1.8-5.9) months. Reasons for drop-out included: 1) patient not wanting to continue because in remission and off-treatment (but not meeting elimination criteria) (n=6), 2) transfer of care to another institution (n=3); and 3) no reason stated (n=8). Two drop-out patients died by nine months. There were no significant differences between drop-outs and those who completed the study.

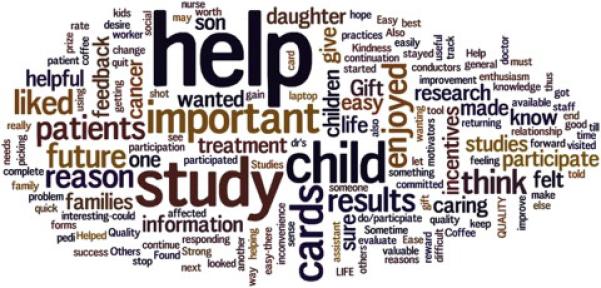

Reasons to Stay in the PediQUEST Study

Of the 104 enrolled patients, 45% completed the participation survey. All but two respondents were more than satisfied with participation. Lack of time (n=9) and child not having energy to fill-out the surveys (n=9) were the most commonly reported issues that challenged participation. When asked about the main factor that kept families enrolled in the study, the themes that emerged were “study was easy, no reason to stop” (n=14), “to help others” (n=13), “children enjoyed incentives” (n=10), and “study was relevant” (n=7). Respondents’ answers are also graphically summarized in Fig. 5 as a word cloud, i.e., a proportional representation of all open-ended responses obtained. When asked about researchers’ actions that helped participation, flexible study procedures and staff pleasantness were most frequently cited.

Fig. 5.

Reasons to stay enrolled in the PediQUEST randomized controlled study. This “word cloud” provides a proportional representation of all open-ended responses to the question “Which was the main factor that kept you in the (PediQUEST) study all the way?” Word size relates to the number of times the word appears. Graph built online using wordle.com application.

Intermittent Attrition

During the nine-month follow-up, 1669 eligible PQ opportunities were identified. Fig. 4 area graph shows number of eligible PQ opportunities and survey administration status over time. Table 2 presents details of eligible PQ opportunities including administered and not administered surveys, and intermitent attrition. PediQUEST was administered 920 times (55%), a median of eight times per patient (IQR 4-12). Surveys were more likely to be administered when eligible PQ opportunities occurred in clinic (61%) than on the ward (40%), or home (13%) (P<0.0001). Only 2% of surveys were incomplete. Patients self-reported 94% of the time (adolescents 99%). Most “not administered” surveys were missed opportunities; when patients declined to answer surveys it was because of feeling ill (8%) or not being interested (7%). Monthly IA showed a two-phase plateau pattern: around 41% up to 20 weeks, jumping to 58% thereafter. IA was unrelated to gender, age, study arm, type of cancer, or drop-out.

Table 2.

Feasibility of longitudinal measurement of electronic patient reported outcomes in children enrolled in the PediQUEST Randomized Controlled Trial during 9-month follow-up and at end-of-life.

| Eligible Opportunities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (n=1669) | In last 12 weeks of life (n=165) | |||

| Location | No. | % | No. | % |

| Clinic | 1364 | 82 | 99 | 60 |

| In-patient facilities | 211 | 13 | 54 | 33 |

| Home | 94 | 5 | 12 | 7 |

| Administered surveys | 920 | 55 | 64 | 39 |

| Location | ||||

| Clinic | 832 | 90 | 48 | 75 |

| In-patient facilities | 84 | 9 | 14 | 22 |

| Home | 12 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Incomplete surveys | 18 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| Administration time, in min | ||||

| Median | 9.3 | 9.5 | ||

| IQR | (6.0,15.4) | (7.1, 17.8) | ||

| Child self-report | ||||

| All children | 777/826 | 94 | 49/55 | 89 |

| 5-12 years old | 321/367 | 88 | 16/23 | 70 |

| 13 years old and over | 456/459 | 99 | 31/32 | 97 |

| Not Administered surveys | 749 | 45 | 101 | 61 |

| Reasons for no administration | ||||

| Missed opportunities | 465 | 62 | 60 | 59 |

| Patient not available/unreachable | 133 | 18 | 20 | 20 |

| Patient feeling too ill or upset | 59 | 8 | 14 | 14 |

| Patient not interested | 49 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| Staff missed patient | 37 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Technical problems | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Intermittent Attritiona | ||||

| All patients (weeks from study entry) | ||||

| Weeks 1-20 | ||||

| Median | 41 | |||

| IQR | (36, 45) | |||

| Weeks 21-39 | ||||

| Median | 58 | |||

| (55, 62) | ||||

| At end of life (weeks before death) | ||||

| Weeks 12-9 | ||||

| Median | 45 | |||

| IQR | (38, 51) | |||

| Weeks 8-5 | ||||

| Median | 65 | |||

| IQR | (60, 73) | |||

| Weeks 4-1 | ||||

| Median | 73 | |||

| IQR | (58, 88) | |||

Intermittent attrition: Proportion of PQ-surveys not administered over total number of PQ-survey administration opportunities that occurred during the indicated period. IQR: Interquartile range

Regarding IA at end of life, of the 26 deaths, 25 patients completed at least one survey in the last 12 weeks of life and had 165 eligible PQ opportunities over the nine-month period (Table 2). Sixty-four surveys were administered (39%). Surveys were also more likely to be administered if the patient was in clinic. Reasons for not administering surveys (n=101) were similar to the whole sample. Median IA was 58% (IQR 50-80%) and increased as death approached. Half of the patients completed their last survey five weeks or less before death (IQR 2-9).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report on the feasibility of conducting a multicenter longitudinal PPC RCT in children with advanced cancer. Although requiring enrollment to continue for five years, our results demonstrate that such RCTs are feasible: we reached a sufficient sample and were able to retain 84% of subjects; families welcomed the opportunity to participate and did so for altruistic reasons; children/teenagers were willing to self-report and longitudinal measurement showed acceptable intermittent attrition for up to 20 weeks of follow-up. Strategies that helped us meet our goals included shortening the proposed follow-up (with optional re-enrollment), low burden study procedures, use of incentives, and research staff's pleasantness and flexibility. Amidst this success, some challenges remain: not unlike those reported among adults (8, 11), pre-inclusion attrition was high and introduced selection bias; enrollment rate was low (one patient per site per month); and adherence with longitudinal data collection could be improved, especially at end of life.

This was a pilot study with a limited target sample (n=120). Even so, and despite using (as suggested in the literature (30)) comprehensive identification procedures and sensitive enrollment strategies, enrolling 104 patients took almost five years at three high-volume sites. Considering that most palliative care interventions have moderate effect sizes, an increase in enrollment capacity is imperative. Our results suggest that higher and faster enrollment could be achieved, at least partly, by devising strategies to increase the number of sicker patients approached, prevent exclusion of certain patient groups, and limit family refusals.

About 20% of identified eligible patients (n=48) were clinically unstable and died a few months after being identified; at least a similar number (n=43) were missed by study procedures. Our recruitment procedures, which lead to a median of 39 days between eligibility and enrollment, may have limited sicker patients’ families’ opportunities to choose to participate. Expert opinion suggests that preventing participation of this relevant population might be unethical (8). In our study, and consistent with a recent systematic review (19), participating families agreed that research was not burdensome or intrusive, and many reported they appreciated the opportunity to express their altruism. We observed that shortening the proposed follow-up improved accrual but not the approach of sicker patients. Approaching these patients can be difficult for research staff and be deemed inappropriate for IRBs and primary providers (8, 15). Strategies that may help recruit sicker patients include appropriate research staff training, using clinicians as recruiters, or using an advanced consent process, obtained at early stages of disease progression and put into effect later when the patient fully meets eligibility (15).

Although overt provider gatekeeping was low (9%) and not associated with the patient's clinical status, the fact that patients with specific diagnoses were less likely to be identified or approached, and difficulties in verifying eligibility, suggest subtle gatekeeping behaviors that could account for up to 30% of pre-inclusion attrition. We did not explore providers’ reasons, but the literature suggests providers have reservations about palliative care research (15, 19). Gatekeeping may be reduced by educating providers about families’ perceptions of research participation, combined with department policies and professional associations’ statements(31) supporting palliative and supportive care research.

Family refusals accounted for 16% of pre-inclusion attrition and seemed to be driven by parents’ views on the study and their child's preference, and not related to illness. The low response rate among non-enrollees to the "Consent survey" precluded further analysis of their reasons for declining participation. Drivers of refusal need to be better understood to devise more effective recruitment strategies.

Even if all these attrition sources were overcome, and assuming sicker patients may enroll at a lower rate, enrollment at most would have been increased to two patients per month per site, underscoring the necessity of multicenter efforts to increase the evidence base of PPC.

Post-inclusion attrition was well within the expected range, below what has been previously reported (9, 15), and did not seem to introduce bias, but rather reflected typical paths in a palliative care study (8). Early enrollment has been proposed as a way of ensuring retention at end of life (30) and may have helped our high retention rates.

Intermittent attrition up to the twentieth week of enrollment was around the recommended 40% threshold (28), possibly indicating an optimal follow-up period. Most of this attrition, even at end of life, resulted from potentially reversible causes such as missed opportunities or other human factors, and occurred more when patients were at home or admitted. Web-based applications, which would allow for ubiquitous and flexible administration, may increase adherence and provide an ideal platform for multicenter studies. Research on the utility and implementation (32) of web tools may further increase feasibility of these RCTs.

In conclusion, rigorous PPC research in children with advanced cancer is feasible, and most families are willing to participate, often for altruistic reasons. This study informs future research by providing estimates of enrollment and attrition and identifying successful recruitment and retention strategies. Successful PPC intervention studies in children with advanced cancer require, however, large multicenter studies. Research efforts and funding should move in this direction.

Acknowledgments

The PediQUEST study (Evaluation of Pediatric Quality of Life and Evaluation of Symptoms Technology in Children with Cancer) was supported by grants NIH/NCI 1K07 CA096746-01, Charles H. Hood Foundation Child Health Research Award, and American Cancer Society Pilot and Exploratory Project Award in Palliative Care of Cancer Patients and Their Families. Funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, analysis of the data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Drs. Wolfe and Dussel had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of data analysis.

The authors are grateful to the families for their willingness to participate in the study; to Sarah Aldridge, CPNP-AC, CPHON, Lindsay Teittinen, ARNP, Janis Rice, MPH, Karen Carroll, BS, and Karina Bloom, BS, for their exceptional work on enrollment, data collection, and administrative support; to Bridget Neville, MPH for her assistance in data management and coding; and Laura Requena, Sociologist, for her help with qualitative analysis. Each named individual was compensated for his or her contribution as part of grant support. We thank the DFCI Clinical Research Informatics team lead by Jomol Mathew, PhD, and members of the Pediatric Palliative Care Research Network for their dedicated efforts toward the completion of the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01838564

Disclosures

All authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care . Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. National Consensus Project; Pittsburgh, PA: 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute . The NCI strategic plan for leading the nation to eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer. U.S.Department of Health And Human Services; 2007. Available at: http://strategicplan.nci.nih.gov/pdf/nci_2007_strategic_plan.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die : improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. Institute of Medicine Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hinds PS, Pritchard M, Harper J. End-of-life research as a priority for pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21:175–179. doi: 10.1177/1043454204264386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bensink ME, Armfield NR, Pinkerton R, et al. Using videotelephony to support paediatric oncology-related palliative care in the home: from abandoned RCT to acceptability study. Palliat Med. 2009;23:228–237. doi: 10.1177/0269216308100251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds PS, Brandon J, Allen C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in end-of-life research in pediatric oncology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1079–1088. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hinds PS, Burghen EA, Pritchard M. Conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology. West J Nurs Res. 2007;29:448–465. doi: 10.1177/0193945906295533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande G, et al. Evaluating complex interventions in end of life care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11:111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinck GC, van den Bos GA, Kleijnen J, et al. Methodologic issues in effectiveness research on palliative cancer care: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1697–707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gysels M, Higginson IJ. Improving supportive and palliative care for adults with cancer: Research evidence manual. National Institute of Clinical Excellence; London, U.K.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ. ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat Med. 2013;27:885–898. doi: 10.1177/0269216312467489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westcombe AM, Gambles MA, Wilkinson SM, et al. Learning the hard way! Setting up an RCT of aromatherapy massage for patients with advanced cancer. Palliat Med. 2003;17:300–307. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm769rr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh K, Jones L, Tookman A, et al. Reducing emotional distress in people caring for patients receiving specialist palliative care. Randomised trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:142–147. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kutner J, Smith M, Mellis K, et al. Methodological challenges in conducting a multi-site randomized clinical trial of massage therapy in hospice. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:739–744. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Wurzelmann J, et al. Enhancing enrollment in palliative care trials: key insights from a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:139–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:3027–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLachlan SA, Allenby A, Matthews J, et al. Randomized trial of coordinated psychosocial interventions based on patient self-assessments versus standard care to improve the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4117–4125. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.21.4117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMillan SC, Weitzner MA. Methodologic issues in collecting data from debilitated patients with cancer near the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:123–129. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gysels MH, Evans C, Higginson IJ. Patient, caregiver, health professional and researcher views and experiences of participating in research at the end of life: a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan GJ, Craig B, Grant B, et al. Home videoconferencing for patients with severe congential heart disease following discharge. Congenit Heart Dis. 2008;3:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0803.2008.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gibson F. The ASyMS©-YG Study: Final Report. 2011 Available at: http://www.londoncancer.org/media/59987/asyms-study-2011.pdf.

- 22.Lyon ME, Jacobs S, Briggs L, Cheng YI, Wang J. A longitudinal, randomized, controlled trial of advance care planning for teens with cancer: anxiety, depression, quality of life, advance directives, spirituality. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:710–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.10.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanhoff D, Hesser T, Kelly KP, et al. Facilitating accrual to cancer control and supportive care trials: the clinical research associate perspective. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1119–1126. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Howard KI, Cox WM, Saunders SM. Attrition in substance abuse comparative treatment research: the illusion of randomization. NIDA Res Monogr. 1990;104:66–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tait AR, Voepel-Lewis T, Malviya S. Participation of children in clinical research: factors that influence a parent's decision to consent. Anesthesiology. 2003;99:819–825. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janson SL, Alioto ME, Boushey HA. Attrition and retention of ethnically diverse subjects in a multicenter randomized controlled research trial. Control Clin Trials. 2001;22:236S–243S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(01)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Judson TJ, Bennett AV, Rogak LJ, et al. Feasibility of long-term patient self-reporting of toxicities from home via the Internet during routine chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2580–2585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.6804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzocato C, Sweeney C, Bruera E. Clinical research in palliative care: patient populations, symptoms, interventions and endpoints. Palliat Med. 2001;15:163–168. doi: 10.1191/026921601668441770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Razzak M. Palliative care: ASCO provisional clinical opinion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:189. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bradford N, Armfield NR, Young J, Smith AC. The case for home based telehealth in pediatric palliative care: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]