Abstract

Introduction

Suicide rates have risen considerably in recent years. National workplace suicide trends have not been well documented. The aim of this study is to describe suicides occurring in U.S. workplaces and compare them to suicides occurring outside of the workplace between 2003 and 2010.

Methods

Suicide data originated from the Census of Fatal Occupational Injury database and the Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. Suicide rates were calculated using denominators from the 2013 Current Population Survey and 2000 U.S. population census. Suicide rates were compared among demographic groups with rate ratios and 95% CIs. Suicide rates were calculated and compared among occupations. Linear regression, adjusting for serial correlation, was used to analyze temporal trends. Analyses were conducted in 2013–2014.

Results

Between 2003 and 2010, a total of 1,719 people died by suicide in the workplace. Workplace suicide rates generally decreased until 2007 and then sharply increased (p=0.035). This is in contrast with non-workplace suicides, which increased over the study period (p=0.025). Workplace suicide rates were highest for men (2.7 per 1,000,000); workers aged 65–74 years (2.4 per 1,000,000); those in protective service occupations (5.3 per 1,000,000); and those in farming, fishing, and forestry (5.1 per 1,000,000).

Conclusions

The upward trend of suicides in the workplace underscores the need for additional research to understand occupation-specific risk factors and develop evidence-based programs that can be implemented in the workplace.

Introduction

Suicide remains a serious concern, both in the U.S. and globally.1 Suicide is responsible for nearly one million deaths annually, including more than 36,000 Americans.2,3 Suicide rates have risen considerably in the U.S., and in 2009, suicides surpassed motor vehicle crashes as the leading cause of injury mortality.4 Besides the devastating emotional impacts on the victim’s family and friends, suicides are costly. On average, suicides result in an estimated $45 billion in worker loss and medical costs every year in the U.S.5 Even though these are substantial numbers, there are several interventions and approaches that have been shown to significantly impact suicide rates. These include educating physicians to screen and recognize clinical depression, restricting access to lethal means, and educating important “gatekeepers” who have contact with potentially vulnerable populations.6

Many sociodemographic, medical, and economic factors have been examined in relation to suicide risk. The literature on occupation and suicide, albeit somewhat limited, has consistently identified several occupations to be at high risk for suicide: farmers,7–10 medical doctors,11,12 law enforcement officers,13–16 and soldiers.17–19 One hypothesis that may explain the increased suicide risk among specific occupations is the availability and access to lethal means, such as drugs for medical doctors and firearms for law enforcement officers.20 Workplace stressors and economic factors have also been found to be linked with suicide in these occupations.21

Although the literature on occupation and suicide is limited, there is even less research examining suicides that occur in U.S. workplaces. There are several reasons why an individual may consider suicide in the workplace. For example, attempting suicide in the workplace would protect family and friends from discovering the deceased individual in a home environment. Recent literature has shown that the 2008 global economic crisis is linked with increased suicide rates in European and North American countries, and it is important to ascertain if these suicide trends extend into the workplace.22 Therefore, the purpose of this article is to enumerate suicides occurring in U.S. workplaces between 2003 and 2010 and compare workplace trends to suicides occurring outside of the workplace using nationally representative data sources.

Methods

Data Sources

Suicides occurring in U.S. workplaces between 2003 and 2010 were obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injury (CFOI) database. The CFOI compiles data on all fatal work-related injuries occurring to non-institutionalized people on the premises of their employer or working off-site. In addition to death certificate data, the CFOI uses multiple administrative and public records, including workers’ compensation reports, Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) investigation reports, medical examiner reports, news media, and police reports. These data originated from restricted access research files under a memorandum of agreement between BLS and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Annual denominator data for rate calculations were extracted from the 2013 BLS Current Population Survey (CPS). The CPS includes data on 60,000 civilians aged ≥15 years who are non-institutionalized wage and salary workers, the self-employed, part-time workers, or unpaid workers in family enterprises in order to create nationally representative workforce estimates.23 Workers aged ≤15 years were removed from the CPS and CFOI prior to analysis. This research project was exempt from IRB because it involved decedents.

Prior to analyses, military occupations (Standard Occupational Classification Code 55) were removed. This was done because the CPS does not include military personnel, so rates could not be calculated. Also, inclusion criteria for the CFOI is different from those for Department of Defense (DoD) or Veterans Affairs (VA) databases that are used to track military fatalities. CFOI does not include fatalities on foreign soil or suicides that occur while individuals are not on duty. Therefore, it is likely that the number of CFOI military suicides is an underestimate. Because of this uncertainty in both the numerator and denominator, this occupational group was excluded.

Suicides occurring outside of the workplace were obtained from CDC’s Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting Systems (WISQARS) database.24 These were termed “non-workplace” suicides. WISQARS data are compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) using national death certificate data from the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS).25 The online WISQARS database also contains population counts based on U.S. census data, which were used for rate calculations.26 Suicides and suicide rates were obtained for age, race, sex, year, and cause of injury categories.26 Prior to analysis, counts of CFOI workplace suicides were removed from WISQARS counts to avoid double-counting fatalities. Also, suicides among those aged r15 years were removed. Because specific age ranges were used, suicide rates were not age adjusted.

Definitions

The CFOI uses Occupational Injury and Illness Classifıcation System (OIICS) codes to classify the nature of injury, body part affected, source of injury, and injury event.27 Workplace suicides were selected using the following event codes: 6200, self-inflicted injury, unspecified; 6210, suicide, attempted suicide; and 6220, self-inflicted injury/fatality, intent unknown. Additionally, all non-classifiable events (codes 9000) were manually examined to include missed or misclassified suicides. No additional cases were added. Major and minor occupational groups were defined using the 2000 Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system, which classifies occupations based on performed work, education, training, and credentials.28 A list of the 2000 SOC codes can be found here: www.bls.gov/soc/2000/socguide.htm#LINK2.

Non-workplace suicides were selected from WISQARS using the intent/manner of injury variable. Cause-of-death data were based on information from death certificates completed by attending physicians, medical examiners, or coroners.24 These were precoded using the ICD-10 (X60.0–X84.9, Y87.0, and U03).29

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed in 2013–2014. Workplace suicide rates for 2003–2010 were calculated as the total number of suicides divided by the estimated number of workers and expressed as the number of fatalities per 1,000,000 workers per year. Non-workplace suicide rates were calculated using population-level census data as the denominator. Sociodemographics of the decedent (age, race, and ethnicity) were compared with rate ratios (RRs) and 95% CIs. Suicide rates were calculated and compared between major and minor occupations. Autoregressive models were used to assess trends of suicide rates and account for serial correlation inherent with time series data. A first-order autoregressive error structure, AR(1), was assumed for the autoregressive models. Durbin–Watson statistics using the residuals of the fitted models were evaluated to ensure that serial correlation was sufficiently accounted for in the AR(1) model. As the Durbin–Watson statistic for all trend models evaluated with an AR(1) error structure were non-significant, no higher-order autoregressive models were considered. Linear and quadratic models were assessed to determine the best fit to the workplace and non-workplace suicide data. The p-value of the quadratic parameter for year was evaluated to determine if it provided a better fit for the trend analysis than a linear parameter. All trend analyses were performed with the Proc Autoreg function in SAS, version 9.3, and all autoregressive models were estimated employing the Yule–Walker method.

Results

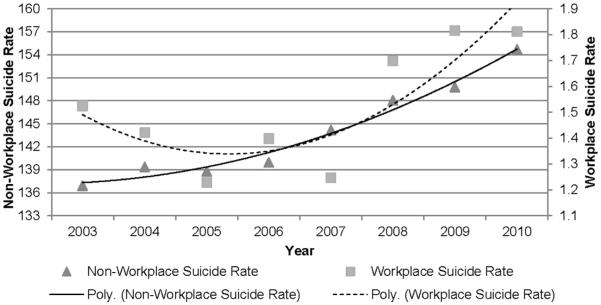

Slightly more than 1,700 people died by suicide in the workplace between 2003 and 2010 in the U.S., for an overall rate of 1.5 per 1,000,000 workers (Table 1). Between 2003 and 2010, a significant quadratic trend in workplace suicides was observed (p=0.035). Workplace suicides decreased between 2003 and 2007 and then sharply increased (Figure 1). During the study period, 270,500 people died by suicide outside of the workplace, for an overall rate of 144.1 per 1,000,000 people. A significant quadratic trend was also observed for non-workplace suicides (p=0.025). Non-workplace suicides increased over the study period; however, the year-to-year increase became larger toward the end of this time period.

Table 1.

Number and Rate of Suicides Occurring in the Workplace and Non-workplace: CFOI and WISQARS, 2003–2010

| Year | Workplacea | Non-Workplaceb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Suicides | Denominator (CPS) |

Rate per 1,000,000 |

Suicides | Denominator (census) |

Rate per 1,000,000 |

|

| 2003 | 210 | 137,735,800 | 1.5 | 30,846 | 225,306,629 | 136.9 |

| 2004 | 198 | 139,252,000 | 1.4 | 31,761 | 227,888,633 | 139.4 |

| 2005 | 174 | 141,729,600 | 1.2 | 31,990 | 230,540,584 | 138.8 |

| 2006 | 202 | 144,427,100 | 1.4 | 32,674 | 233,456,688 | 140.0 |

| 2007 | 182 | 146,046,500 | 1.2 | 34,054 | 236,185,097 | 144.2 |

| 2008 | 247 | 145,362,400 | 1.7 | 35,371 | 238,867,600 | 148.1 |

| 2009 | 254 | 139,877,500 | 1.8 | 36,165 | 241,424,041 | 149.8 |

| 2010 | 252 | 139,064,000 | 1.8 | 37,639 | 243,275,505 | 154.7 |

| Total | 1,719 | 1,133,494,800 | 1.5 | 270,500 | 1,876,944,777 | 144.1 |

Note: Suicide totals and rates were generated by the authors with restricted access to CFOI microdata.

83 military and 2 “unknown” age suicides removed from the total workplace suicides.

Total non-workplace suicides from WISQARS excludes the total counts of workplace suicides from CFOI (1,719) plus the 83 military cases from CFOI.

CPS, Current Population Survey; CFOI, Census of Fatal Occupational Injury; WISQARS, Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting Systems.

Figure 1.

Rates per 1,000,000 for suicides occurring in the workplace and non-workplace by year: CFOI and WISQARS, 2003–2010.

Note: Suicide rates were generated by the authors with restricted access to CFOI microdata. “Poly” refers to the use of a quadratic term in the suicide rate model.

CFOI, Census of Fatal Occupational Injury; WISQARS, Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting Systems.

Table 2 displays suicides and rates by age, gender, and race. For both non-workplace and workplace suicides, men had signifıcantly higher rates compared to women (RR=4.0, 95% CI=4.0, 4.0, and RR=15.3, 95% CI=12.1, 18.5 , respectively). Generally, as age increased, so did workplace suicide rates until age 75 years. Those aged between 65 and 74 years had the highest suicide rate of all ages (2.4 per 1,000,000). Non-workplace suicide rates increased with age until age 55 years, when rates decreased until age 75 years. Among non-workplace suicides, the highest rates were found among those aged 45–54 years (175.2 per 1,000,000). Eighty-nine percent of workplace suicides occurred among whites; however, people with an unknown or “other” (includes those of multiple races) race had the highest workplace suicide rates (2.1 per 1,000,000). Whites had the highest non-workplace suicide rate (160.8 per 1,000,000).

Table 2.

Rates per 1,000,000 and Rate Ratios of Workplace and Non-workplace Suicides by Demographics: 2003–2010

| Workplace | Non-Workplace | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Suicides (%) |

Total no. of workers |

Rate per 1,000,000 |

RR (95% CI) |

Suicides (%) |

Population | Rate per 1,000,000 |

RR (95% CI) |

|

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 1,626 (95) | 604,099, 800 | 2.7 |

15.3

(12.1, 18.5) |

213,916 (79) |

911,917,479 | 234.6 |

4.0

(4.0, 4.0) |

| Female | 93 (5) | 529,395,100 | 0.2 | 1 | 56,584 (21) | 965,027,298 | 58.6 | 1 |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| 16–24 | 100 (6) | 152,546,200 | 0.7 | 1 | 32,534 (12) | 307,880,355 | 105.7 | 1 |

| 25–34 | 225 (13) | 245,748,800 | 0.9 |

1.4

(1.1, 1.7) |

41,503 (15) | 318,872,403 | 130.2 |

1.2

(1.2, 1.2) |

| 35–44 | 425 (25) | 268,597,200 | 1.6 |

2.4

(1.9, 2.9) |

52,619 (20) | 342,250,953 | 153.7 |

1.5

(1.4, 1.5) |

| 45–54 | 560 (33) | 267,538,300 | 2.1 |

3.2

(2.5, 3.9) |

60,703 (22) | 346,506,137 | 175.2 |

1.7

(1.6, 1.7) |

| 55–64 | 307 (18) | 155,243,100 | 2.0 |

3.0

(2.3, 3.7) |

39,066 (14) | 259,059,685 | 150.8 |

1.4

(1.4, 1.4) |

| 65–74 | 85 (5) | 34,999,800 | 2.4 |

3.7

(2.6, 4.8) |

20,388 (8) | 158,404,106 | 128.7 |

1.2

(1.2, 1.2) |

| ≥75 | 17 (1) | 8,821,500 | 1.9 |

2.9

(1.4, 4.5) |

23,687 (9) | 143,971,138 | 164.5 |

1.6

(1.5, 1.6) |

| Racea | ||||||||

| White | 1,524 (89) | 933,337,200 | 1.6 |

2.5

(1.9, 3.1) |

245,174 (91) | 1,524,346,842 | 160.8 |

2.4

(2.4, 2.5) |

| Black | 80 (5) | 122,764,200 | 0.7 | 1 | 15,645 (6) | 235,449,985 | 66.4 | 1 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander, American Indian, Alaskan Native |

84 (5) | 62,526,000 | 1.3 |

2.1

(1.5, 2.6) |

9,681 (3) | 117,147,950 | 83.7 |

1.3

(1.2, 1.3) |

| Other, Unknown | 31 (2) | 14,867,500 | 2.1 |

3.2

(1.9, 4.0) |

– | – | – | – |

| Total | 1,719 (100) |

1,133,494,800 | 1.5 | – | 270,500 (100) |

1,876,944,777 | 144.1 | – |

Note: Boldface indicates statistical significance of rate ratios (p<0.05). Suicide totals and rates were generated by the authors with restricted access to CFOI microdata.

Original race categories for the CFOI: white; black or African American; American Indian or Alaskan Native; Asian; Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; other (includes persons of multiple races); not reported or unknown. Original race categories for WISQARS: white; black; American Indian/Alaskan Native; Asian/Pacific Islander; and other.

CFOI, Census of Fatal Occupational Injury; RR, rate ratio; WISQARS, Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting Systems.

The major occupation with the highest workplace suicide rate was Protective Service Occupations (5.3 per 1,000,000) (Table 3). This major occupation included supervisors of protective service workers, firefighting and prevention workers, law enforcement workers, and other protective service workers (animal control workers, private detectives and investigators, and miscellaneous protective service workers). All occupations within this group had rates in excess of the national average of 1.5 per 1,000,000. Those in Farming, Fishing, and Forestry occupations had the next highest rate (5.1 per 1,000,000). Those in Installation, Maintenance, and Repair occupations also had high workplace suicide rates (3.3 per 1,000,000). Overall, firearms were used in 48% of work-place suicides (n=828), but this differed by occupation. Among Building and Grounds Cleaning occupations, 29% of suicides involved firearms, and among those in protective services, 84% were committed using a firearm (n=108). Among those in Farming, Fishing, and Forestry, 50% of suicides involved a firearm and 50% were due to other causes, primarily strangulation.

Table 3.

Rate per 1,000,000 of suicides occurring in the workplace by selected major occupation: CFOI, 2003–2010

| Occupation | Total no. of workers | Gunshot (%) | All other (%) | Totala (%) | Rate per 1,000,000 workers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33-Protective service occupations | 23,976,400 | 108 (84) | 20 (16) | 128 (7) | 5.3 |

| Supervisors of protective service workers, firefighting & prevention workers, law enforcement workers, other protective service workers (animal control workers, private detectives & investigators, miscellaneous protective service workers) |

17,054,100 | 80 (92) | 7 (8) | 87 (5) | 5.1 |

| Security guards and gaming surveillance officers | 6,922,300 | 28 (68) | 13 (32) | 41 (2) | 5.9 |

| 45-Farming, fishing, & forestry occupations | 7,839,600 | 20 (50) | 20 (50) | 40 (2) | 5.1 |

| 49-Installation, maintenance, & repair occupations | 40,963,400 | 58 (42) | 79 (58) | 137 (8) | 3.3 |

| Automotive body/service repairers and technicians | 8,325,500 | 22 (42) | 30 (58) | 52 (3) | 6.2 |

| 1st line supervisors/managers of mechanics, installers, repairers | 2,690,800 | 11 (58) | 8 (42) | 19 (1) | 7.1 |

| Maintenance and repair workers general | 3,100,500 | 9 (41) | 13 (59) | 22 (1) | 7.1 |

| All other | 26,846,700 | 16 (36) | 28 (64) | 44 (3) | 1.6 |

| 53-Transportation & material moving occupations | 68,402,400 | 55 (33) | 110 (67) | 165 (10) | 2.4 |

| Truck drivers | 26,401,000 | 34 (42) | 47 (58) | 81 (5) | 3.1 |

| Laborers and freight stock and material movers hand | 14,423,700 | 5 (16) | 26 (84) | 31 (2) | 2.1 |

| All other | 27,577,800 | 16 (29) | 37 (70) | 53 (3) | 1.9 |

| 11-13 Management occupations, business, & financial operations occupations |

167,954,600 | 189 (58) | 139 (42) | 328 (19) | 2.0 |

| Farmers and ranchers | 6,189,700 | 37 (60) | 25 (40) | 62 (4) | 10.0 |

| Food service managers | 7,623,300 | 20 (59) | 14 (41) | 34 (2) | 4.5 |

| Construction managers | 8,024,400 | 16 (62) | 10 (38) | 26 (2) | 3.2 |

| All other | 146,117,200 | 116 (56) | 90 (44) | 206 (12) | 1.4 |

| 37-Building & grounds cleaning & maintenance occupations | 42,346,600 | 25 (29) | 60 (71) | 85 (5) | 2.0 |

| Janitors and cleaners | 16,715,400 | 7 (19) | 29 (81) | 36 (2) | 2.2 |

| Landscaping and grounds keeping workers | 9,828,700 | 8 (33) | 16 (66) | 24 (1) | 2.4 |

| All other | 15,802,500 | 10 (40) | 15 (60) | 25 (1) | 1.6 |

| Other/Unknown | 782,011,800 | 373 (44) | 463 (55) | 836 (49) | 1.1 |

| Total | 1,133,494,800 | 828(48) | 891 (52) | 1,719 (100) |

1.5 |

Note: Suicide totals and rates were generated by the authors with restricted access to CFOI microdata.

denotes column percentage

CFOI, Census of Fatal Occupational Injury

Discussion

This research provides a national description of work-place suicides using a well-established occupational surveillance system spanning many years. Also, by comparing these to non-workplace suicides, trends and risk factors could be described and compared. Trends in workplace and non-workplace suicides differed across the 8-year period. Workplace suicides decreased until 2007, when a large increase was found. Comparatively, non-workplace suicides gradually increased throughout the study period. There were differences between workplace and non-workplace suicides in relation to sociodemographics. Racial minorities appear to be at a greater risk for workplace suicide compared to non-workplace suicides. Finally, this research confirmed that those in farming and protective service occupations had high workplace suicide rates. This research revealed a relatively new finding that those in automotive repair and installation occupations also had high workplace suicide rates. Finally, this study also appears to support the hypothesis that access to lethal means is linked with method-specific suicides in certain occupations, such as firearm-related deaths among those in protective services.

This study identified workers of “other” (including those of multiple races) and “unknown” race as having the highest workplace suicide rates. This was an unexpected finding, as previous research30,31 reported higher workplace suicide rates for whites compared to blacks only. Also, these findings differ from other work32 demonstrating disparities in work-related unintentional fatalities and homicides among racial minorities. Many potential reasons for this disparity, beyond that of racial discrimination, exist. First, although differences in unsafe or unhealthy occupational tasks and exposures by race may exist, the etiology of suicide involves a complicated process that cannot simply be explained by unsafe work tasks and exposures.33 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis34 has suggested that education, income, and employment status warrant inclusion in research investigating work-related suicide. Without inclusion of these factors, workplace suicide rates among race may be confounded by these socioeconomic variables. These variables are not normally collected in national fatality databases, and we could not control for them in our study. Therefore, racial disparities in suicide risk found here could still be in large part due to education, income, and employment status, as these factors remain strongly tied to race. Proposed conceptual models guiding suicide research should include both race/ethnicity and class (income, education, occupation, and employment status) to achieve progress in better understanding workplace suicides.

The workplace suicide rate for protective service occupations was 3.5 times greater than the overall U.S. worker rate, and 84% of these suicides involved firearms. These findings are consistent with other studies using different methodologies and databases.13–16,35–37 Contributing factors for the high suicide rate among protective service occupations include increased access to lethal means, shiftwork, and high-stress work experiences.13–16,35–37 Details concerning firearm ownership (service issued or privately owned) are not available in the CFOI, but prior research has shown that access to lethal means and socialization of officers to firearms may increase their suicide risk.15 Violanti et al.35 found increased suicide ideations among male police officers who worked midnight shifts, potentially due to isolation from fellow officers during late night shifts. Another risk factor for suicide among protective service workers is the high-stress situations that are often part of their normal duties.15,35,36 Exposure to high-stress events can lead to negative mental health outcomes such as post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety disorders, and depression.15,36 Many protective service workers do not seek counseling for these issues because of the fear of being stigmatized.15,16,36 Left untreated, these conditions may lead to higher suicide ideation.15,36

This and other studies7,9,38–40 have documented high suicide rates among those in Farming, Fishery, and Forestry occupations—particularly farmers. Factors that may contribute to this risk include the potential for financial losses, chronic physical illness, social isolation, work–home imbalance, depression due to chronic pesticide exposure, and barriers and unwillingness to seek mental health treatment.7,9,10,38,41,42 Farmers may also have a higher workplace suicide risk because of increased access to lethal means.7,9,20,39,40,43 This study, as well as others,7,9,20,39,40,43 have shown that firearms and strangulation by hanging are the two leading methods of suicide in this occupation. Also, access to mental health services can be limited in rural locations, and finding time to leave the farm to receive medical care is challenging.39 Studies7,9,20,39 have suggested that farmers diagnosed with depression or other mental health conditions should be provided timely and accessible care to mental health services.

Another occupational group with high workplace suicide rates was Installation, Maintenance, and Repair. Workers in this occupation had workplace suicide rates that were more than twice as high as the national rate. This finding corresponds with limited prior research44–46 demonstrating an elevated suicide risk among automotive workers. This increased risk has been attributed to solvent exposure with known neurotoxic effects.44 Chronic and long-term solvent exposure can result in memory impairment, irritability, depressive symptoms, emotional instability, and brain damage.44 Recommendations to reduce solvent exposure include thorough and frequent hand cleansing, installation of vapor recovery systems, personal protective equipment, and discontinuing the practice of siphoning solvents by the mouth.44 It is not clear why other occupations that are exposed to similar solvents do not experience high workplace suicide rates.

Implementation of suicide prevention programs in workplaces could not only provide counseling and education to workers and their families but also help to increase suicide awareness in high-risk occupations. The 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention47 encourages community-based settings, such as workplaces, to implement programs that promote wellness and prevent suicide-related behaviors. Although scientific evaluations of workplace suicide prevention programs are rare, Mishara and Martin48 found that a comprehensive workplace suicide prevention program resulted in a significant 79% decrease in suicides among a law enforcement cohort. The three components of the program included a half day–long training session for all officers, a telephone helpline, and a day-long training for supervisors and union representatives.48 A key element suggested for workplace suicide prevention programs is training managers on risk and protective factors and steps to take when risk is identified.49 The WHO report on suicide in the workplace also suggested that a comprehensive workplace approach would involve preventing and reducing job stress, increasing and raising awareness, early detection of mental health difficulties, and intervention and treatment through employee health and assistance programs.50

Limitations

There are limitations to these data. First, using cause-of-death data to categorize suicides can lead to misclassification errors and underestimates of the true count.14,51 Because the CFOI and WISQAR use cause-of-death data, this is an important limitation to note. Second, workplace and non-workplace suicides originated from two different databases. Although we removed workplace suicide counts from WISQARS to avoid double-counting, there is no way to tell if this approach was successful or if CFOI suicides were present in WISQARS to begin with. Third, CFOI only includes suicides that occur at the work site, and CFOI counts may not be a complete census of work-related suicide.52 Suicides occurring outside of the workplace or not on work time may or may not be included, depending on the evidence in the source documents.53 Fourth, workplace suicides were defined by the decedent’s location at the time of the event. Therefore, it is important to point out that workplace suicides may or may not be motivated by work-related exposures or factors.53 Fifth, although excluding military occupations was necessary given the data issues, this is a limitation given the high suicide rates of returning soldiers and veterans. Finally, this analysis is limited to decedents and does not consider workers who have attempted suicide or had suicidal ideations; therefore, it does not capture the full spectrum of workplace suicidal behavior.

Conclusions

Occupation can largely define a person’s identity and psychological risk factors for suicide, such as depression and stress, can be affected by the workplace. Also, as the lines between home and work continue to blur, personal issues creep into the workplace and work problems often find their way into employees’ personal lives. A more comprehensive view of work life, public health, and work safety could enable a better understanding of suicide risk factors and how to address them. Suicide is a multi-factorial outcome and therefore multiple opportunities to intervene in an individual’s life—including the workplace—should be considered. A method that may reduce the burden of suicide suggested by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention Research Prioritization Task Force was increasing the number of people trained for suicide assessment and risk management.54 Implementing effective and evidence-based programs for the training of these individuals is pivotal.55 The workplace should be considered a potential site to implement such programs and train managers in the detection of suicidal behavior, especially among the high-risk occupations identified in this paper.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.WHO . Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/131056/1/9789241564779_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . Public health action for the prevention of suicide: a framework. Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. www.who.int/mental_health/publications/prevention_suicide_2012/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . National Survey on Drug Utilization and Health. USDHHS; Rockville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockett IR, Regier MD, Kapusta ND, et al. Leading causes of unintentional and intentional injury mortality: United States, 2000– 2009. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(11):84–92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300960. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC . Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS): cost of injury reports. Atlanta, GA: http://wisqars.cdc.gov:8080/costT/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher LM, Kliem C, Beautrais AL, Stallones L. Suicide and occupation in New Zealand, 2001-2005. J Occup Environ Health. 2008;14(1):45–50. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2008.14.1.45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2008.14.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stallones L, Doenges T, Dik BJ, Valley MA. Occupation and suicide: Colorado, 2004-2006. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56(11):1290–1295. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Browning SR, Westneat SC, McKnight RH. Suicides among farmers in three southeastern states, 1990-1998. J Agric Saf Health. 2008;14(4):461–472. doi: 10.13031/2013.25282. http://dx.doi.org/10.13031/2013.25282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dongre AR, Deshmukh PR. Farmers' suicides in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra, India: a qualitative exploration of their causes. J Inj Violence Res. 2012;4(1):2–6. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v4i1.68. http://dx.doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v4i1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, et al. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic, and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1131–1140. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707000487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawton K, Agerbo E, Simkin S, et al. Risk of suicide in medical and related occupational groups: a national study based on Danish case population-based register. J Affect Disord. 2011;134(1-3):320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.044. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vena JE, Violanti JM, Marshall J, Fiedler RC. Mortality of a municipal worker cohort: III—police officers. Am J Ind Med. 1986;10:383–397. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700100406. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.4700100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Violanti JM. Suicide or undetermined? A national assessment of police suicide death classification. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2010;12(2):89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Hara AF, Violanti JM. Police suicide—a web surveillance of national data. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2009;11(1):17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Violanti JM, Vena JE, Marshall JR, Petralia MS. A comparative evaluation of police suicide rate validity. Suicide Threat Behav. 1996;26(1):79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyman J, Ireland R, Frost L, Cottrell L. Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty U.S. military population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S138–S146. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300484. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former U.S. military personnel. JAMA. 2013;10(5):496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.65164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bossarte RM, Knox KL, Piegari R, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of suicide ideation and attempts among active military and veteran participants in a national health survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S38–S40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300487. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Skegg K, Firth H, Gray A, Cox B. Suicide by occupation: does access to means increase the risk? Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(5):429–434. doi: 10.3109/00048670903487191. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00048670903487191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kposowa AJ. Suicide mortality in the United States: differentials by industrial and occupational groups. Am J Ind Med. 1999;36(6):645–652. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199912)36:6<645::aid-ajim7>3.0.co;2-t. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199912)36:6o645::AID-AJIM743.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang SS, Stuckler D, Yip P, Gunnell D. Impact of 2008 global economic crisis on suicide: time trend study in 54 countries. BMJ. 2012;347:1–15. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bureau of Labor Statistics . Chapter 1: Labor Force Data received from the Current Population Survey. U.S Department of Labor; Washington, DC: BLS Handbook of Methods. www.bls.gov/opub/hom/homch1_a.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 24.CDC . Web-based injury statistics query and reporting systems: fatal injury reports. Atlanta, GA: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/fatal_injury_reports.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Kockanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final Data for 2007. USDHHS, CDC, National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. www.cdc.gov/NCHS/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_19.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CDC . Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) Atlanta, GA: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bureau of Labor Statistics . Occupational injury and illness classifıcation manual. U.S. Department of Labor; Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Office of the President, Office of Management and Budget . Standard Occupational Classification Manual. Bernan Associates; Lanham, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.WHO . International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva, Switzerland: 1992. 10th revision. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boxer PA, Burnett C, Swanson N. Suicide and occupation: a review of the literature. J Occup Env Med. 1995;37(4):442–452. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199504000-00016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00043764-199504000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conroy C. Suicide in the workplace: incidence, victim characteristics, and external cause of death. J Occup Med. 1989;31(10):847–851. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198910000-00011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198910000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron S, Steege A, Marsh S, Chaumont Menéndez C, Myers J. Examining occupational health and safety disparities using national data: a cause for continuing concern. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:527–538. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22297. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.22297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray LR. Sick and tired of being sick and tired: scientific evidence, methods, and research implications for racial and ethnic disparities in occupational health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):221–226. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.221. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.2.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milner A, Spittal MJ, Pirkis J, LaMontagne AD. Suicide by occupation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203:409–416. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128405. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.128405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Violanti JM, Charles LE, Hartley TA, et al. Shift-work and suicide ideation among police officers. Am J Ind Med. 2008;51(10):758–768. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20629. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Violanti JM, Mnatsakanova A, Burchfiel CM, et al. Police suicide in small departments: a comparative analysis. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2012;14(3):157–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aamodt MG, Stalnaker NA. Police Officer Suicide: Frequency and Officer Profiles. In: Shehan DC, Warren JI, editors. Suicide and Law Enforcement. Federal Bureau of Investigation; Washington, DC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Judd F, Jackson H, Fraser C, et al. Understanding suicide in Australian farmers. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(1):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0007-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-005-0007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Routley VH, Ozanne-Smith JE. Work-related suicide in Victoria, Australia: a broad perspective. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19(2):131–134. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2011.635209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2011.635209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersen K, Hawgood J, Klieve H, et al. Suicide in selected occupations in Queensland: evidence from the state suicide register. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(3):243–249. doi: 10.3109/00048670903487142. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00048670903487142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stark C, Gibbs D, Hopkins P, et al. Suicide in farmers in Scotland. Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(1):509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stallones L, Beseler C. Pesticide poisoning and depressive symptoms among farm residents. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(6):389–394. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00298-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1047-2797(01)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawton K, Fagg J, Simkin S, et al. Methods used for suicide by farmers in England and Wales. The contribution of availability and its relevance to prevention. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:320–324. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.4.320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.173.4.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz E. Proportionate mortality ratio analysis of automobile mechanic and gasoline service station workers in New Hamphsire. Am J Ind Med. 1985;12(1):91–99. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700120110. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ajim.4700120110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson GR, Milham S. Occupational Mortality in the State of California 1959-1961. USDHHS, CDC; Cincinnati, OH: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guralnick L. Mortality by occupation and cause of death among men 20 to 64 years of age, United States, 1950. U.S. Department of Health Education and Welfare, Public Health Service; Washington, DC: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 47.USDHHS. Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention . National strategy for suicide prevention: goals and objectives for action. Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mishara BL, Martin N. Effects of a comprehensive police suicide prevention program. Crisis. 2012;33(3):162–168. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910/a000125. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paul R, Jones E. Suicide prevention: leveraging the workplace. EAP Digest. 2009;29(1):18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO . Preventing Suicide: a resource at work. Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraus JF, Schaffeer K, Chu L, Rice T. Suicides at work: misclassification and prevention implications. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2005;11(3):246–253. doi: 10.1179/107735205800245984. http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2005.11.3.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bureau of Labor Statistics Occupational suicide: census of fatal occupational injuries fact sheet. www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/cfoi/osar0010.pdf.

- 53.Pegula SM. An analysis of workpalce suicides; 1992-2001. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Compensation and Working Conditions. 2004 www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/cwc/an-analysis-of-workplace-suicides-1992-2001.pdf.

- 54.National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention: Research Prioritization Task Force . A Prioritized Research Agenda for Suicide Prevention: An Action Plan to Save Lives. National Institute of Mental Health and Research Prioritization Task Force; Rockville, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Osteen PJ, Frey JJ, Ko J. Advancing training to identify, intervene, and follow up with individuals at risk for suicide. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 suppl 2):S216–S221. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]