Abstract

Background

Eliminating health disparities in racial ethnic minority and underserved populations requires a paradigm shift from disease-focused biomedical approaches to a health equity framework that aims to achieve optimal health for all by targeting social and structural determinants of health.

Methods

We describe the concepts and parallel approaches that underpin an integrative population health equity framework. Using a case study approach we present the experience of the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) in applying the framework to guide its work.

Results

This framework is central to CSAAH’s efforts moving towards a population health equity vision for Asian Americans.

Discussion

Advancing the health of underserved populations requires community engagement and an understanding of the multilevel contextual factors that influence health. Applying an integrative framework has allowed us to advance health equity for Asian American communities and may serve as a useful framework for other underserved populations.

Health inequalities and health inequities are terms often used interchangeably for describing a disproportionate burden of disease in some communities and the factors that affect both population health and disparities. However, both of these terms represent two distinct dimensions along the continuum of improving health outcomes for all populations—sharing common themes of addressing the social determinants of health. Research on addressing health inequalities, often referred to as health disparities research, implies targeted efforts on closing gaps in health status experienced by disadvantaged populations. In contrast, the shift to addressing health inequities employs a social justice lens that requires a deeper focus on engaging communities, employing a life course perspective, and tackling the structural determinants that produce social and health inequalities. Interventions to ameliorate health disparities have been targeted and tailored to reach special populations, accounting for the social and environmental context by which health disparities emerge but often are limited in their impact to affect structural determinants. Health inequities research, on the other hand, seeks to affect change in underserved and disparity populations by focusing on structural determinants, such as policies and systems that improve access to care or environmental interventions to improve the built-in environment, as well as incorporating the life course approach through early intervention programs for at-risk communities.

Recently, the call for advancing a national health equity agenda1 reflects a nuanced shift to achieving the highest attainment of health for all, thus simultaneously moving towards the vision of improving total population health and reducing health inequities in underserved and minority communities. While existing research has focused primarily on documenting health disparities, there is limited work on developing strategies to address the multiple levels and complexity of influence that are needed to achieve health equity. Greater attention is needed in three areas: 1) Developing targeted interventions for addressing disparities through increased awareness, education, and behavioral change targeting all perspectives and stakeholder groups; 2) Working with multiple health and non-health sectors for health improvement of all populations, with a focus on health disparity communities; and 3) Developing targeted strategies that address structural determinants related to health inequities that are rooted in social position, racism and discrimination, and access to social and health resources.

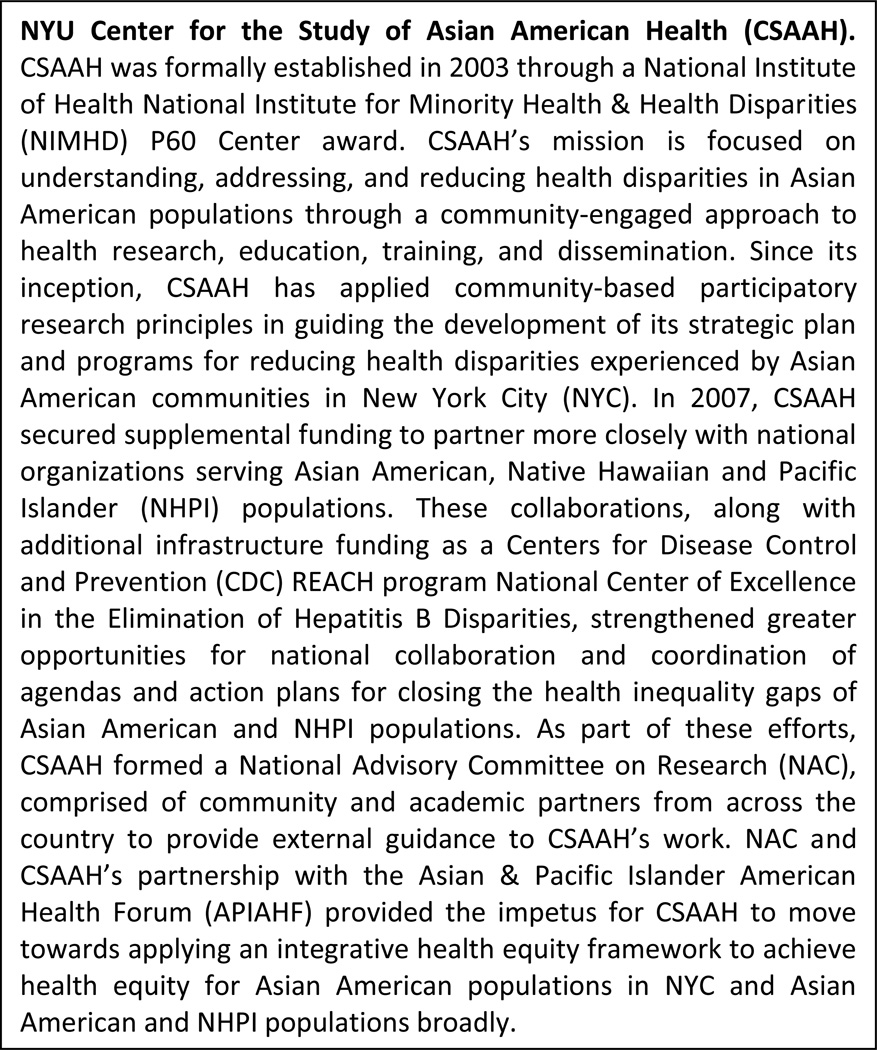

Population health interventions are often policy, systems and environmental (PSE) level in nature, focused on upstream interventions for reaching the wider population and yielding broad improvements in net outcomes. Often these strategies and interventions are based on research conducted in the majority dominant population—largely white and middle-class—and not representative of health disparity populations. Thus, in some cases, population-wide strategies have made little impact on eliminating the gradients in health and have widened the health disparities gap on a community-level. Strategies to bridge these frameworks call for a coherent and integrated paradigm for advancing both population health and health equity. We propose an integrative population health equity framework that draws upon and incorporates several approaches for advancing health equity. We define the different models and approaches, and present examples from the experience of the New York University Center for the Study of Asian American Health (CSAAH) in identifying and understanding the nature of inequalities and inequities in New York City (NYC) Asian American populations (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health

Methods

Using examples from our research, we describe the concepts and parallel approaches that have been applied in shaping an integrative population health equity framework. This framework, largely informed by community partners serving Asian Americans, has been central to guiding CSAAH’s work in moving towards a population health equity vision for Asian American populations.

Definitions and Implications: Health Inequality, Health Inequity, Health Equity, and Population Health

Several major concepts of health inequality, health inequity, health equity, and population health have informed our work and are defined below.

Health Inequalities and Health Inequities

Health inequality refers to a known disparity in health status or access to care that characterizes a disproportionate burden of disease or utility of services among persons or groups within a population.2 In contrast, a health inequity reflects the social justice lens of defining a disparity that is avoidable, unjust, and unfair. In essence, a moral value judgment is attached to the drivers of health inequities. Although health inequalities and health inequities are distinct and nuanced, both terms have been used interchangeably with the discourse commonly infused with concepts related to social structure, institutional and environmental racism, and neighborhood disadvantage.

Health inequities are best understood within a complex, multi-level framework that incorporates determinants that are both social—including the impact of normative and cultural values—and structural—including those policies that influence social position, access to quality education, and residential segregation. Addressing health inequities begins, then, with understanding the challenges that often occur at birth, that continue on in early childhood and adolescence, and evolve into greater likelihoods of pervasive social and health disadvantages in adulthood and in future generations of children born into this cycle. Critical to understanding the confluence of these factors on each other and on future generations of children requires a life course perspective. This approach relies on the strength of partnership building, community mobilizing, and developing shared goals and initiatives with non-health sectors and policymakers to systematically address and eliminate social and structural inequities across the life span.

In our own work at CSAAH, we perceive substantial overlap in the scope of health inequalities and health inequities, while understanding them to reflect slightly different facets of the challenges our research approach seeks to address. Reducing health inequalities requires contextualizing interventions at the individual, organizational, and community levels to ensure improved and sustainable behavioral change and access to care. For many Asian American communities which reflect a largely immigrant population, there is an added complexity of understanding the role of migration experiences, acculturative stress, and familial obligations from their home countries on social position and health. For instance, our efforts to reduce health inequalities are focused on closing current gaps in health status experienced by disadvantaged populations, through community health worker interventions that seek to improve positive health contexts, behaviors, and outcomes at the individual and family level while recognizing the role of global factors on local Asian American communities, many of whom have extended ancestral and familial roots in their countries of origin.3–10

In contrast, reducing health inequities requires a targeted focus on tackling social determinants of health that are structural in nature at the PSE level and influence the life course trajectories of risk for individuals and their communities. For example, CSAAH supports advocacy and policy change efforts that support improved access to basic healthcare, education, and other social programs (such as early childhood) for socially disadvantaged and immigrant populations. These efforts are rooted in a worldview towards altering the conditions and risks that occur across the lifespan and that engender social and health inequities for entire communities and future generations of children.

Health Equity and Population Health

Health equity aims at achieving the highest attainment of health for all populations. The population health approach recognizes that there are multiple determinants of health.11 Kindig and Stoddart define population health as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within a group,” at its core however, the concept of population health is varied.12 Central to both health equity and population health frameworks are that they underscore the significance of understanding and addressing the social (and structural) determinants of access to care, health status and health inequities through community-engaged and multi-sectorial approaches. Secondly, both frameworks promote the use of models that bridge the interface between socially disadvantaged and medically underserved communities with complex health care delivery systems—emphasizing the need to streamline linkages between medicine and public health.13

The Health Impact Pyramid: A population health equity strategy

Thomas Frieden, MD, MPH, Director of the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), outlines a five-tier health impact pyramid demonstrating the impacts of varying types of public health interventions—moving from high population impact and low individual effort at the base of the pyramid, to lower population impact and increasing individual effort at the top.14 Although addressing socioeconomic factors and PSE levels have the greatest potential population impact, Frieden notes that these types of efforts often have significant barriers, particularly in political commitment and will. In addition, different types of interventions may be the most effective or feasible in any given context and for different public health issues. Frieden therefore recommends implementing interventions at each of the levels to maximize synergy, public health impact, and long-term success.14 Moreover the CDC’s Division of Community Health,2 formed under Dr. Frieden’s leadership, includes a population-wide approach to achieve health equity as one of its three core principles and recognizes the need for the use of a ‘twin’ approach that encompasses both targeted interventions for socially disadvantaged and medically underserved communities and population-wide interventions using a health equity lens to maximize health impact.15–17 The other two core principles are focused on maximizing public health impact and the use and expansion of the evidence base.18

Approaches applied in the integrative population health equity framework

The integrative population health equity framework draws on six main approaches and models: the social determinants of health, the life course perspective, community-based participatory research (CBPR), social marketing, health in all policies, and bridging clinical practice and community-based health promotion.

Social determinants approach

This perspective recognizes that the conditions in which people live, work and play are primary drivers of health inequalities and inequities.19 Social determinants include socioeconomic status, social structure, social position, racism and discrimination as well as factors such as housing, transportation, political environment and cultural beliefs and norms. These individual and socioeconomic contextual factors interact to influence the health of populations.

NYC is home to the largest Asian American population in the US. There are more than one million Asian Americans in NYC, making up 13% of the total population.20 The largest Asian subgroups are Chinese (48%), followed by Asian Indian (19%), Korean (8%), and Filipino (6%). Asian Americans in NYC experience a binomial distribution when it comes to economic and educational indicators. Approximately 25% of Asian Americans in NYC have no high school diploma, while 41% hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, and an additional 10% have a graduate or professional degree.21 While median household income is $53,384, nearly one quarter (23%) of families with children under 18 years of age live in poverty. Additionally, there are unique cultural and language barriers that impede access to healthcare and adherence to provider recommendations for disease prevention and management.21 Over 71% of the Asian American population in NYC is foreign born, while 81% of Asian Americans in NYC speak a language other than English at home. Nearly half of Asian Americans in NYC have limited English proficiency (47%), nationally the Census reports that less than 50% of those who spoke Korean, Chinese, or Vietnamese spoke English “very well.”22,23 NYC’s Asian senior population has more than doubled in the last decade and statewide has grown by 75%, representing the fast growing senior citizen population in the city.21

In many respects, the study of Asian Americans in NYC and nationally is the study of the health of immigrant populations. A substantial proportion of Asian Americans are first- and second-generation immigrants (66%) are foreign born overall in the U.S).22 Moreover, immigrants and their children now comprise over 24% of the US population.24 Thus a cross-national social determinants framework for immigrant health25 can provide understanding of how and why disparities occur and persist in Asian American and other immigrant populations. A cross-national lens that integrates both a social determinants and life course perspective recognizes the distinct and interacting contextual factors that shape and influence health that are rooted in the context of both source and destination countries, taking into account the layered complexity of the immigrant experience, including migration context and processes.

Life Course Perspective Approach

The life course perspective is the study of long term effects that risk and cumulative exposures have on health over the lifespan.26 Underlying a life course perspective is the worldview of the inherent role of social position and social structure on health over time. The cumulative effects of negative exposures on health imply an increasing vulnerability to such influences on health outcomes that differs across age groups.27 For example, the very young and older populations experience increased vulnerability compared to middle-aged adults. A life course approach provides an important opportunity to explore health and disease both vertically (downstream vs. upstream determinants) and horizontally (impact on individuals and communities over time). Moreover, for immigrant populations, it allows for the important consideration of socioeconomic status in source and destination countries. The socioeconomic conditions as well as the infectious and environmental exposures experienced in an immigrant child’s source country may influence the health of the immigrant adult in destination country.

CSAAH’s community partnerships and coalitions that guide the research reflect diverse community perspectives allowing us to consider factors such as nativity and immigration history that inform life course perspectives, as well as including intergenerational approaches, to health promotion and disease prevention. For example, in our diabetes management initiative in the Bangladeshi community,5 we have found that engaging a diverse range of stakeholders has been an important means of ensuring the project represents both first and second generation immigrant concerns and needs. The project coalition has worked closely with traditional partners such as faith-based organizations and ethnic media outlets to engage largely first generation immigrant communities, but also partners with student associations and ethnic sport leagues (such as cricket leagues) to support an intergenerational approach that reaches a wide spectrum of Bangladeshi men and women at different ages. These partnerships have been particularly important in engaging the community around diabetes prevention and management of the disease in younger populations, as well as promoting family-based intervention models and dialogues around diabetes.

Community-based Participatory Research

Paralleling the emergence of population health frameworks is the recognition that there is an enormous time gulf from the development and validation of evidence-based therapies, dissemination of recommended guidelines for prevention and treatment, and finally their adoption and uptake in clinical and community settings. The emergence of translational research reflects this concern and the importance of engaging communities in the research process in order to improve the development of relevant interventions and, ultimately, more effective adoption of evidence-based interventions. Often, interventions found to be effective in rigorously controlled clinical trials fail in the uptake, practice, and adoption in real world community and clinical settings because these trials often to do not account for the contextual factors that regulate or mediate behavior, health status, and access to care. As a consequence, community engagement and the practice of CBPR is increasingly viewed as a vital part of translational research science, as well for efforts to improve population health, eliminate health inequalities, and achieve health equity.

The lack of data disaggregated by Asian ethnic sub-group is a critical and persistent gap in understanding, addressing, and advocating for funding and resources that support identified community needs. Disaggregated data is needed to identify the most prevalent disparities, the sub-groups that are experiencing them, the nature of why they exist and persist, and the best strategies for mitigating them given limited resources. To address this gap, CSAAH developed and implemented two rounds (2004 and 2014) of a large-scale Community Health Resource and Needs Assessments (CHRNA) in diverse, low-income Asian American communities in NYC using a participatory and community venue-based approach to assess existing health issues, available resources, and best approaches to meet community needs. The CHRNA survey was developed through the adaptation of existing surveys, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), in partnership with key community leaders and community-based organizations who identified and prioritized health topic areas for survey inclusion, and guided and review the translation to ensure comprehension and cultural relevancy into multiple Asian languages, including Vietnamese, Khmer, Korean, Tibetan, Bengali, Nepali, and Chinese. Partnering with community groups, surveys are administered in-language at community venues during cultural events, community meetings, and faith-based gatherings. This method ensures that underserved and hard-to-reach immigrant populations are surveyed. Importantly, the second round of surveys will allow CSAAH to assess population health improvements, changes in risk and protective factors, and population changes in the last decade, including newly arriving communities such as the Bhutanese and Burmese, thereby filling a large gap in our understanding of the health needs and priorities of emerging Asian communities.

Social Marketing Approach

Healthy People 2020 identifies health information communication as an important concept for improving the health of all Americans and includes “Increase social marketing in health promotion and disease prevention” as one of its developmental objectives28 and the CDC includes social marketing as a key framework in the dissemination of evidence-based health promotion practices.29 Social marketing is the application of principles drawn from the commercial sector to influence a target audience to engage in beneficial behavioral change for the promotion of health and well-being.30 Social marketing principles are especially well-suited for translating complex educational messages and behavior change techniques into concepts and products that will be received and acted upon by a specific segment of the audience.31 A meta-analysis of tailored health behavior change interventions reported a significant effect for using tailored health messages over a generic "one-size-fits-all" approach.32 The application of social marketing principles have been a key CSAAH strategy in culturally tailoring health education and outreach materials and intervention strategies across health initiatives including hepatitis B, mammography screening campaigns, and PSE protocols and strategies. It has also informed all CSAAH dissemination activities to ensure that research and intervention findings and outcomes are being presented in a meaningful and user-friendly way for real world application.

Health in All Policies Approach

The complexity of social and health inequities indicate that a trans-sectorial approach is needed for improved population health and reduction of health disparities and health inequities. Essentially, a health in all policies approach is a collaborative approach that recognizes that health and prevention are impacted by policies that are managed by non-health government and non-government entities. This approach recognizes that while health is not an outcome of social policies, social policies indeed exert direct and indirect influences on health. Integration of health objectives in social and other public planning can ultimately have far greater impact on advancing both population health and health equity for socially disadvantaged populations. In that vein, CSAAH leadership has participated on the New York State Department of Health Medicaid Redesign Team to provide feedback and guidance on policies that influence Medicaid delivery and reimbursement and have implications for reducing health disparities and improving access to care for minority and medically underserved communities. Efforts have included improved disaggregated health data collection for racial and ethnic minority communities, strategies to integrate community health workers in strengthening community-clinical linkages, workforce development, and stable housing for health disparity and vulnerable populations.

CSAAH is also active with Project CHARGE (Coalition for Health Access to Reach Greater Equity), a health collaborative founded in 2007 by the Coalition for Asian American Children and Families (CACF) consisting of 16 community partners that work together to address health access for Asian Pacific Americans in New York City.33 Through participation in the Coalition, CSAAH has been able to educate city and state elected officials on the needs of Asian American communities, and advocate for data disaggregation, language access, health care access, and targeted health outreach and education. Through our relationship with CACF and Project CHARGE, CSAAH and 8 additional community-based organizations serving Asian American communities across the city have received funding to serve as In-Person Assistors (IPAs)/Navigators for the NY State of Health insurance marketplace, providing culturally competent, linguistically appropriate, in-person enrollment assistance to individuals, families, small businesses and their employees.

Bridging Clinical Practice and Community-based Health Promotion

A key research priority for CSAAH is to develop interventions that improve access to health care for prevention and better management of health disparity conditions. Community health worker (CHW) approaches are central to many of CSAAH’s protocols and resonate for communities served by CSAAH. CHWs play a critical role in bridging clinical practice and community-based health promotion for many underserved and immigrant populations, including Asian American communities. We have seen in our own work the efficacy and effectiveness of CHW interventions in the community.4,5,7 We are now moving towards better integration and sustainability of CHWs in clinical care teams and care coordination models.34 For example, through the recently funded NYU-City University of New York Prevention Research Center (NYU-CUNY PRC), we are implementing an integrated CHW-electronic health record intervention to address hypertension management in South Asian populations, working closely with a range of health systems partners, including payer organizations, state and local departments of health, and provider networks, with the ultimate goal of enhancing sustainability and scalability of the CHW model (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Integrative framework for population health equity: NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health

Results

Application of the integrative population health equity framework

Hepatitis B is the largest health disparity experienced by Asian Americans. While less than 0.5% of the US population is infected with hepatitis B, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis B infection among Asian Americans is estimated to be between 9 and 15%, and may be as high as 25% in select subgroups of recent immigrants.35–39 Hepatitis B is endemic in Asian countries and exposure is largely due to transmission during childbirth and passed from mother to child. In the late 1990s, Asian American-serving community based organizations, community health clinics, advocates, hospitals, physician associations and community leaders came together to address the substantial disparities in hepatitis B infection and disease outcomes in Asian immigrant communities in NYC. This community driven coalition then reached out to two additional stakeholders to create a multi-sectorial coalition, a local policy maker on the City Council of New York and CSAAH, an academic research center. By 2003, the Asian American Hepatitis B Coalition (AAHBP) was formalized and with funding from the NYC Council was transformed from a series of unaffiliated, sporadic community-based hepatitis B screening programs into a community-based comprehensive hepatitis B screening, vaccination, and treatment program that enabled the establishment of a centralized, epidemiological hepatitis B data registry.40 Data collected was informed using a social determinants of health lens to understand social, economic, cultural, and migration factors that influence access to care.

AAHBP is an example of a community-clinical linkage model reaching underserved communities through trusted community-based organizations for outreach and recruitment in community settings for education and screening and using community health workers and navigators.41 Due to the program’s success, the AAHBP Coalition, with CSAAH as the lead agency, were awarded a 5 year CDC grant from 2007–2012 to serve as a national research center of excellence: B Free CEED.42 As its mission, B free CEED had a multi-pronged strategy to address hepatitis B disparities: 1) Identify and build the evidence-base on understanding hepatitis B-related health disparities; 2) Develop and assess scalable model programs; 3) Raise awareness and tailor education to diverse stakeholder groups; and 4) Train and build capacity at the community and provider level.

Applying an integrative population health equity framework has been used to implement these strategies. For example, B Free CEED worked to compile and analyze existing data to inform local and national policy-level efforts in support of best practices to address hepatitis B-related disparities. For example, after several years of advocacy, in May 2014 the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated their prior 2004 guidance issuing a “B” grade for hepatitis B screening of populations at high risk for infection, including foreign-born individuals from countries with a 2% or higher HBV prevalence rate.43 A “B” grade USPSTF recommendation ensures healthcare providers will increase hepatitis B screening in Asian immigrant and other high-risk populations and that insurance plans will reimburse for the testing which had previously not been a reimbursable screening test. B Free CEED partner organizations also advocated for the inclusion of hepatitis-B related issues on other policy-related issues including data collection and disaggregation and allocation of funds and services for children and family issues.

B Free CEED also undertook a comprehensive evaluation of our community-clinical linkage model thus highlighting the importance of contextual factors in determining the true burden of hepatitis B prevalence and disease burden.40 For example, we determined that the burden of hepatitis B and its complications is expected to be higher in areas populated by Asians emigrating from countries and specific geographic areas with higher hepatitis prevalence. Thus, migration history and pattern likely explains the large variation in hepatitis B prevalence that has been reported in studies conducted in Asian immigrant communities across the US and that future studies and efforts to estimate hepatitis B prevalence need to take into consideration contextual factors including the country and geographic area of birth among immigrant populations.

Social marketing principles and a CBPR approach was used by B Free CEED to develop and implement the Be Certain Campaign targeted to high-risk Korean and Chinese immigrants to screen for hepatitis B. The campaign includes messaging and visuals that are meaningful and relevant to the community and empowers and builds on community-based assets and strengths. Formative data was collected to understand existing knowledge and socio-cultural contextual information on the target community. These data were shared with an agency focused on the Asian American market and through a consensus process the campaign elements were chosen, pilot tested and refined. Formative data also informed the channels and optimal community-based locations for the dissemination of the campaign. Using a convenience sample of 112 Chinese and Korean target community members, a campaign assessment indicated that before seeing the campaign, the majority of respondents reported high levels of stigma and discrimination related to hepatitis B. After viewing the campaign, over 90% reported feeling “somewhat” or “very comfortable” discussing hepatitis B. Furthermore, 96% of Korean and 60% of Chinese participants reported that they were “likely” or “very likely” to get tested or urge others to test for hepatitis B (p=0.001). From September 28, 2013 – April 25, 2014, the campaign was chosen for inclusion in the “Health is a Human Right: Race and Place in America” exhibit at the David J. Sencer Centers for Disease and Control Museum (See Figure 3).44

Figure 3.

Be Certain Get Tested Campaign at the “Health is a Human Right: Race and Place in America" Exhibit David J. Sencer Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Museum September 28, 2013 - April 25, 2014

Image Source: David J. Sencer Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Museum44

The capacity of community-based organizations was also built and fostered the implementation of community-specific tailored strategies to address hepatitis B health disparities through the Legacy Pilot Program. Small, one-year grant awards along with technical assistance and training were provided to community-based organizations across the US. In total, $500,000 was allocated over 5-years to fund 21 Legacy projects across the US. The goal of these Legacy projects was to build a national community network of organizations, agencies, and coalitions conducting evidence-based, community-based activities to address hepatitis B-related health disparities in the Asian American communities.

Discussion

To date, little progress has been made in advancing health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority populations. We propose an integrative population health equity framework that includes advocacy, translation of research findings through communication and adaptation and meaningful implementation of culturally relevant strategies and policies that address the complex and multilevel challenges of health promotion for underserved, culturally diverse populations. This integrative approach has allowed us to advance health equity for Asian American communities in NYC and may serve as a useful framework for other underserved racial and ethnic minority populations.

Health disparities and inequities facing Asian Americans are complex, multilevel, and tightly entrenched within larger social, political, historical and economic constructs. The case examples explored suggest that the integrated and applied framework we developed has been a useful guide in creating a shared vision and strategies for reaching the vision of health equity within an academic-community partnership. Applying various lenses and approaches has encouraged us to address larger political, social, cultural and economic forces that impact health outcomes, moving away from a biomedical approach to one that is social determinant in nature and disease-agnostic in its emphasis, and has informed the development, implementation, and dissemination of sustainable strategies and programming within the communities that we serve.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants: P60MD000538 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities; 1U48DP001904, 1U48DP005008-01, and U58DP004685 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and UL1TR000038 from the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding organizations.

The authors would also like to thank the following individuals and organizations for their guidance and support on CSAAH and this manuscript: Mariano J. Rey, MD at the NYU School of Medicine and S. Darius Tandon, PhD at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine for their support in addressing Asian American health disparities through participatory approaches; Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum and the National Advisory Committee for Health Disparities Research for their leadership and guidance in moving towards a health equity agenda for Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander populations; Chandak Ghosh, MD MPH at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Health Resources and Services Administration Stella Yi, PhD, Julie Kranick, MS, and Shilpa Patel, MPH at the NYU School of Medicine and Nancy Van Devanter, DrPH RN at the NYU College of Nursing for their review and suggestions on the manuscript; and the numerous community and academic partners and student interns and volunteers that offered their time and assistance throughout the NYU Center for the Study of Asian American Health’s development.

Contributor Information

Chau Trinh-Shevrin, Email: chau.trinh@nyumc.org.

Smiti Nadkarni, Email: smiti.nadkarni@nymc.org.

Rebecca Park, Email: rebecca.park@nyumc.org.

Nadia Islam, Email: nadia.islam@nyumc.org.

Simona C. Kwon, Email: simona.kwon@nyumc.org.

References

- 1.Srinivasan S, Williams SD. Transitioning from health disparities to a health equity research agenda: the time is now. Public health reports (Washington, D.C. :1974) 2014 Jan-Feb;129(Suppl 2):71–76. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) Division of Community Health (DCH): Making Healthy Living Easier. 2014 http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/.

- 3.Islam NS, Zanowiak JM, Wyatt LC, et al. Diabetes prevention in the New York City Sikh Asian Indian community: a pilot study. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2014 May;11(5):5462–5486. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110505462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ursua RA, Aguilar DE, Wyatt LC, et al. A community health worker intervention to improve management of hypertension among Filipino Americans in New York and New Jersey: a pilot study. Ethnicity & disease. 2014 Winter;24(1):67–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islam N, Riley L, Wyatt L, et al. Protocol for the DREAM Project (Diabetes Research, Education, and Action for Minorities): a randomized trial of a community health worker intervention to improve diabetic management and control among Bangladeshi adults in NYC. BMC public health. 2014;14(1):177. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Islam NS, Zanowiak JM, Wyatt LC, et al. A randomized-controlled, pilot intervention on diabetes prevention and healthy lifestyles in the New York City Korean community. Journal of community health. 2013 Dec;38(6):1030–1041. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9711-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Islam NS, Wyatt LC, Patel SD, et al. Evaluation of a community health worker pilot intervention to improve diabetes management in Bangladeshi immigrants with type 2 diabetes in New York City. The Diabetes educator. 2013 Jul-Aug;39(4):478–493. doi: 10.1177/0145721713491438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Islam NS, Tandon D, Mukherji R, et al. Understanding barriers to and facilitators of diabetes control and prevention in the New York City Bangladeshi community: a mixed-methods approach. American journal of public health. 2012 Mar;102(3):486–490. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ursua R, Aguilar D, Wyatt L, et al. Awareness, treatment and control of hypertension among filipino immigrants. Journal of general internal medicine. 2014 Mar;29(3):455–462. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2629-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braveman P. What is health equity: and how does a life-course approach take us further toward it? Maternal and child health journal. 2014 Feb;18(2):366–372. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kindig D, Asada Y, Booske B. A population health framework for setting national and state health goals. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2081–2083. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kindig D, Stoddart G. What Is Population Health? [2003/03/01];American journal of public health. 2003 93(3):380–383. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.3.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gourevitch M. Population health and the academic medical center: the time is right. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):544–549. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieden TR. A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. American journal of public health. 2010 Apr;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milstein B, Homer J, Briss P, Burton D, Pechacek T. Why behavioral and environmental interventions are needed to improve health at lower cos. Health Affairs. 2011;30(5):823–832. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahern J, Jones M, Bakshis E, Galea S. Revisiting rose: comparing the benefits and costs of population-wide and targeted interventions. Milbank Quarterly. 2008;86(4):581–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00535.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diez Roux A. The study of group-level factors in epidemiology: rethinking variables, study designs, and analytical approaches. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2004;26:101–111. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Division of Community Health (DCH) Making Healthy Living Easier. [Accessed September 23, 2014];2014 http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dch/about/index.htm.

- 19.Marmot M, Friel S, Bell R, Houweling TA, Taylor S. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008 Nov 8;372(9650):1661–1669. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2012 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimate.

- 21.Asian American Federation. Asian Americans of the Empire State: Growing Diversity and Common Needs. New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.2010–2012 American Community Survey 3-Year Estimate.

- 23.Ryan C. Language Use in the United States: 2011. US Census Bureau - American Community Survey Reports. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Census Bureau. Table 4.1: Population by Sex, Age, and Generation: 2010. [Accessed September 30, 2014];Current Population Survey. 2012 http://1.usa.gov/1vBAh0Z.

- 25.Acevedo-Garcia D, Almeida J. Special issue introduction: place, migration, and health. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2055–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International journal of epidemiology. 2002 Apr;31(2):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lynch J, Smith GD. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annual review of public health. 2005;26:1–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Healthy People 2020. Disparities. [Accessed June 13, 2014];2014 http://1.usa.gov/1vBLRZ5.

- 29.Harris JR, Cheadle A, Hannon PA, et al. A framework for disseminating evidence-based health promotion practices. Preventing chronic disease. 2012;9:E22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotler P, Zaltman G. Social marketing: an approach to planned social change. Journal of marketing. 1971 Jul;35(3):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefebvre RC, Flora JA. Social marketing and public health intervention. Health education quarterly. 1988 Fall;15(3):299–315. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noar SM, Palmgreen P, Chabot M, Dobransky N, Zimmerman RS. A 10-year systematic review of HIV/AIDS mass communication campaigns: Have we made progress? Journal of health communication. 2009 Jan-Feb;14(1):15–42. doi: 10.1080/10810730802592239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Semple K. Passing the One Million Mark, Asian New Yorkers Join Forces. New York Times. 2011 Jun 24; [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam NNS, Zahn D, Skillman M, Kwon S, Trinh-Shevrin C. Integrating Community Health Workers within Patient Protection and Affordable Care Implementation. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000084. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin SY, Chang ET, So SK. Why we should routinely screen Asian American adults for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study of Asians in California. Hepatology (Baltimore Md.) 2007 Oct;46(4):1034–1040. doi: 10.1002/hep.21784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hwang JP, Mohseni M, Gor BJ, Wen S, Guerrero H, Vierling JM. Hepatitis B and hepatitis C prevalence and treatment referral among Asian Americans undergoing community-based hepatitis screening. American journal of public health. 2010 Apr 1;100(Suppl 1):S118–S124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.162776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen TT, Taylor V, Chen MS, Jr, Bastani R, Maxwell AE, McPhee SJ. Hepatitis B awareness, knowledge, and screening among Asian Americans. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2007 Winter;22(4):266–272. doi: 10.1007/BF03174128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ha NB, Trinh HN, Nguyen TT, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and disease knowledge of chronic hepatitis B infection in Vietnamese Americans in California. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2013 Jun;28(2):319–324. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0466-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States in the era of vaccination. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010 Jul 15;202(2):192–201. doi: 10.1086/653622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pollack HKS, Wang S, Wyatt L, Trinh-Shevrin C. Chronic hepatitis B and liver cancer risks among Asian immigrants in New York City: Results from a large, community-based screening, evaluation, and treatment program. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0491. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollack H, Wang S, Wyatt L, et al. A comprehensive screening and treatment model for reducing disparities in hepatitis B. Health affairs (Project Hope) 2011 Oct;30(10):1974–1983. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trinh-Shevrin C, Pollack HJ, Tsang T, et al. The Asian American hepatitis B program: building a coalition to address hepatitis B health disparities. Progress in community health partnerships : research, education, and action. 2011 Fall;5(3):261–271. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2011.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement: Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Screening, 2014. [Accessed October 3, 2014];2014 Sep; http://bit.ly/1nTCfcd. [Google Scholar]

- 44.David J. Sencer CDC Museum. Health Is a Human Right: Race and Place in America. 2014. [Accessed October 3, 2014]; http://1.usa.gov/IpjPfA.