Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infects half of the world’s population and plays a causal role in ulcer disease and gastric cancer. This pathogenic neutralophile uniquely colonizes the acidic gastric milieu through the process of acid acclimation. Acid acclimation is the ability of the organism to maintain periplasmic pH near neutrality in an acidic environment to prevent a fall in cytoplasmic pH in order to maintain viability and growth in acid. Recently, due to an increase in antibiotic resistance, the rate of H. pylori eradication has fallen below 80% generating renewed interest in novel eradication regimens and targets. In this article, we review the gastric biology of H. pylori and acid acclimation, various detection procedures, antibiotic resistance and the role that gastric acidity plays in the susceptibility of the organism to antibiotics currently in use and propose several novel drug targets that would promote eradication in the absence of antibiotics.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori; Acid acclimation; UreI; Urease; Carbonic anhydrase; Two component system; Sensor kinase; Response regulator; Peptic ulcer disease; Cyp2C19; Probiotics; Proton pump inhibitors; H,K-ATPase

Introduction

The discovery of the association of gastric infection by Helicobacter pylori with peptic ulcer disease revolutionized medical thought for the treatment of peptic ulcer disease (PUD). With the introduction of H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, it was felt that acid suppression was the means of effective treatment of PUD. However, after introduction of either one of these two classes of drugs, differing in their efficacy of inhibition of acid secretion, it transpired that soon after stopping treatment, PUD returned in about 60% of patients [1]. With the first modern description of infection by H. pylori and its association with regions of ulceration [2], it is now accepted that apart from acid, infection by H. pylori is a major contributing factor to PUD. Hence our treatment of PUD, either to treat the ulcer or to treat ulcer related symptoms has now to include eradication of the infection. To explain the basis for treatment of infection, we have to digress initially and try to understand why this particular organism is the only one known to infect the human stomach. This review focuses on the organism and not the response of the host.

H. pylori is bio-energetically a neutralophile, meaning that it prefers neutral or close to neutral pH (i.e. pH 5.5–7.5) to grow in vitro. Stated differently, this means at more acidic or alkaline pH levels, it does not thrive and in fact may die. However, it seems that its usual environment in the stomach is acidic. The median pH of the human stomach is 1.4, resulting from relatively short periods of high pH as high as 5.0 following ingestion of food to a pH<1.0 in the inter-digestive phase which occupies usually about 16 h per day.

The most common site of infection is the antrum, which is an absorptive rather than a secretory region of the stomach [3]. With a luminal pH of <2.0, whether using fluorescent probes of pH or microelectrodes in the infected mouse stomach [4, 5], there appears to be no barrier to acid reaching the gastric surface, in contrast to the barrier that is there when luminal pH>3.0. Analysis of bacterial gene expression from bacteria present in the gerbil stomach strongly suggested that the habitat of the bacteria in vivo was highly acidic [6]. Hence, the organism has found a way to both survive and grow at acidic pH enabling colonization of human and animal stomachs. We have termed this “acid acclimation” to distinguish it from acid tolerance or resistance mechanisms expressed by many neutralophiles that are able to transit the stomach but not to colonize it [7]. These mechanisms maintain cytoplasmic pH greater than pH 5 or 4 with an external pH of ~2, which prevents death of the organism but is too low for the complex processes necessary for cell division. There are various resistance mechanisms that have been identified such as amino acid/amine counter-transport coupled to cytoplasmic amino acid decarboxylases that consume one proton per decarboxylation of the entering amino acid given that the amine is exported in exchange for the entering amino acid [8]. This helps buffer cytoplasmic pH but has no effect on periplasmic pH. The same is true of the bacterial membrane F1F0 ATP synthase operating in the ATPase mode exporting ~3H+/ATP where the organism cannot afford to expend all its ATP in export of entering acid [9].

Gastric Habitation by H. pylori

The key to acid acclimation is the ability to maintain the periplasm at a relatively neutral pH in the face of high environmental acidity. This of course also helps maintain a relatively neutral cytoplasm in high acidity sharply differentiating acid acclimation from acid tolerance or resistance.

Gastric juice contains significant amounts of urea (1–3 mM) and H. pylori has taken advantage of this to allow gastric colonization. H. pylori is able to acid acclimate because of a very high level of expression of urease in the bacterial cytoplasm [10]. The products of urease in the cell are NH3 and H2CO3. The NH3 can neutralize protons entering the cytoplasm and can also cross the cytoplasmic membrane and consume protons entering the periplasm. It can also leave the cell and elevate the pH of the medium. The H2CO3 is converted to CO2 and H2O by a cytoplasmic β-carbonic anhydrase and the CO2 can transit the inner membrane and is converted in the periplasm to HCO3− by a membrane bound α-carbonic anhydrase. The effective pKa of HCO3− is 6.1 which is the pH maintained in the periplasm even at a medium pH of 2.0 [11].

The activity of bacterial urease, if dependent on passive diffusion of urea would be inadequate in gastric acid since the polarity of urea results in slow diffusion across membranes (4×10−6 cm sec−1). To enhance urea access under acidic conditions, the organism expresses UreI, a H+-gated urea channel that accelerates urea access ~300 fold at a medium pH of 5 [12]. UreI is essential for gastric infection [13, 14] and thus would provide an effective target for eradication. The α-carbonic anhydrase is also important for periplasmic pH homeostasis and is therefore another target for eradication.

The organism is also sensitive to a pH>8.2 hence, although it maintains a basal level of urease activity only 1/3 of its urease is active at neutral pH, to reduce the likelihood of alkalizing the medium. In acid, the urease apoenzyme, consisting of the structural subunits of urease, UreA and UreB, becomes activated due to the insertion of nickel that is required for urease activity by the urease accessory genes, ureE/UreG and UreF/UreH that exist as pairs in the cytoplasm [15]. In addition, in acid, the apoenzyme and these urease accessory genes associate with the inner membrane and thus are able to scavenge entering urea. The association is dependent on the presence of UreI [11, 16]. Moreover, apart from urea transport, UreI catalyzes the transport of the products of urease, NH3, NH4+ and CO2 [17•]. This provides a structured system enabling rapid periplasmic pH control with rather little effect on neutral cytoplasmic pH.

Regulation of the response to acidity is due to two two component systems (TCS’s), HP0165/HP0166 and the cytoplasmic histidine kinase HP0244 whose response regulator for acid responses is unknown. The first of these TCS’s consists of a sensor kinase, HP0165, that responds to acidity by autophosphorylation of a conserved histidine and a response regulator, HP0166, that accepts the phosphate from phosphorylated HP0165 at a conserved aspartate and this regulator binds to DNA activating or repressing genes in the HP0165/HP0166 regulon [18]. Activation of HP0165 results in dimerization of this membrane sensor. The second sensor kinase, HP0244, is required for periplasmic pH homeostasis at low medium pH such as 2.5 [19]. Deletion of either sensor kinase abolishes the membrane trafficking of the urease gene proteins but prevention of phosphorylation of HP0166 has no effect. It may be that the dimerized HP0165 or HP0244 is responsible for the recruitment but the basis for recruitment is unknown. Membrane recruitment is essential for periplasmic pH buffering and is independent of protein synthesis but depends on the presence of nickel and expression of UreI [11].

At neutral pH, UreB is truncated due to a asRNA binding to the 5′ end of ureB resulting in the production of a 1.7 kb message rather than the 2.4 kb full length mRNA. Presumably, this reduces potential urease activity under conditions where it is not required, reducing the possibility of over-alkalization [20].

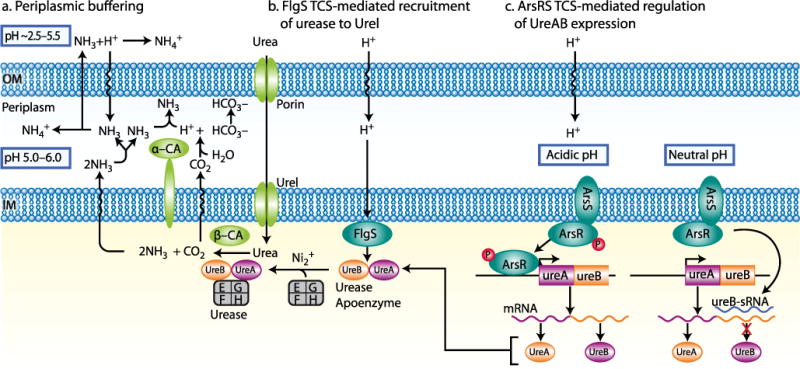

The above data are presented in the model of Fig. 1. There are other genes involved in acid acclimation, to provide cytoplasmic NH3 such as asparaginase, or cytoplasmic urea such as arginase and regulation of these genes is also controlled by TCS’s [18].

Fig. 1.

Periplasmic buffering and regulation by Helicobacter pylori. Urea crosses the outer membrane (OM) and then the inner membrane (IM) through the H+ gated urea channel, UreI, at external pH<6.0. Cytoplasmic urease hydrolyzes urea to 2NH3 + H2CO3, and the latter is converted to CO2 by cytoplasmic β-carbonic anhydrase (β-CA). These gases cross the IM and the CO2 is converted to HCO3− by the membrane bound α-carbonic anhydrase (α-CA), thereby maintaining periplasmic pH at ~6.1, which is the effective pKa (−log10Ka, in which Ka is the acid dissociation constant) of the CO2/HCO3− couple. Exiting NH3 neutralizes the H+ that is produced by carbonic anhydrase as well as the entering H+, and can also exit the OM to alkalize the medium. This allows maintenance of a periplasmic pH that is much higher than the medium (left side) [12, 44, 45]. The role of the pH responsive two component system (TCS) FlgS (encoded by the locus HP0244) in acid acclimation by H. pylori (middle) Activation of this TCS results in recruitment of the urease proteins to UreI: the resultant immediate access of urea to urease and the outward transport of CO2, NH3 and NH4+ through UreI increase the rates of periplasmic buffering and disposal of cytoplasmic NH4+ [12, 13, 44, 45]. A simplified model representing regulation of the expression of the urease apoenzyme genes (ureA and ureB) by the ArsRS TCS (encoded by loci HP0166 (ArsR) and HP0165 (ArsS)). At neutral pH, ArsS is not activated and the response regulator, ArsR, is not phosphorylated. The unphosphorylated ArsR binds to the promoter of the gene encoding a small RNA (ureB-sRNA) that targets the ureB part of the ureAB mRNA, leading to transcription of ureB-sRNA and consqueny truncation of the ureAB mRNA, resulting in a decline in urease activity. This reflects the adaptation to non-acidic pH. At acidic pH, ArsS is activated and ArsR is phosphorylated; the phosphorylated ArsR binds to the ureAB promoter to positively regulated the transcription of ureAB, resulting in upregulation of the ureAB mRNA and a consequent increase in urease activity (right)

Site of Infection

The usual site of infection in the human stomach is the antrum [3]. This may be interpreted as showing that the antrum has the pH at which the organism thrives, rather than the fundus where acid secretion occurs [21]. However, under PPI treatment, the organism is found in the fundus rather than the antrum. This is more than likely due to an inimical increase in the pH of the antrum and a favorable increase of pH in the fundus. In vitro, in the presence of urea and the absence of buffer, the organism dies when the pH is >3.5 due to alkalization of the medium [22]. The stomach, to our knowledge, does not secrete significant quantities of buffer and only with food is there buffering in the stomach, hence, when acid secretion is inhibited, antral pH rises to >3.5 and with continuing gastric urea, the organism perishes in the antrum. On the other hand, with PPIs, median pH rises to >4.0 and thus the fundus becomes the preferred site of infection. A reasonable concept is that normally, H. pylori is found in the transition zone between antrum and fundus at a pH about 3.5 [23], that is also suggested by the transcriptome of the organism derived from infected gerbils [6].

In some patients, there is predominant fundus infection and it is not clear whether this is due to strain variation in the organism or a different pH level in these patients at the surface of the fundus. What is clear, however, is that fundic infection is required for gastric intestinal metaplasia and this may lead to the many fold increase in the incidence of gastric cancer in those patients [24–26]. Hence, it is particularly important to determine whether patients put on chronic PPI therapy are infected and to have the organism eradicated prior to PPI therapy.

Detection of Infection

A total of 80% of infected individuals are symptom free. However, a simple serology test can tell if any patient is or was infected. These tests detect high molecular weight antigens with long half lives, hence are useful for determining if infection was present, but they do not reveal whether the infection is persistent, nor whether eradication has taken place. To evaluate whether there is persistent infection, a variety of tests are available that are also suitable for determination of the success of any eradication protocol. The use of biopsy and organism culture is one recommended procedure but multiple biopsies must be taken since infection is patchy. Another method is to biopsy and run a rapid urease test. Stool PCR analysis for H. pylori urease is accurate. Finally, there is the breath test, where 13C urea is swallowed in a solution made acidic by citric acid and the patient exhales into a special container and the 13CO2 content analyzed either in the physician’s office if the testing equipment is available, or in a central laboratory [27–30]. The basis of this test is the CO2 production from gastric urea carried out by H. pylori. The urease activity of the microbe depends on activation of the pH gated urea channel, UreI, which is why the labeled urea is given in an acidic solution.

Eradication Protocols

The presence of H. pylori in patients with PUD is the primary indication for eradication therapy. In the absence of disease, there is some degree of controversy as to whether the organism is a commensal, i.e. not a pathogen or whether even in the absence of upper GI symptoms, the strategy should be “test and treat” [31•, 32]. To substantiate the commensal concept, some have suggested that simple eradication of H. pylori exacerbates or even induces esophageal reflux disease since gastric acidity may rise since NH3 is no longer being produced in the stomach [31•, 33]. However, the majority of data suggest that only exacerbation is found, but not initiation of GERD. An inverse relationship between H. pylori infection and asthma in children has been stated but the data are not particularly convincing [34]. On the other hand, it is universally agreed that infection results in gastritis with generation of antibodies against H. pylori [35]. This increased immune response has been suggested to negatively influence other immune system mediated diseases but the effect is not large. In our view, the presence of gastritis is very strong evidence that the organism is not a commensal and apart from the liability of PUD or gastric cancer, a test and treat policy should be adopted to avoid these serious side effects of infection.

Current therapies require the administration of inhibitors of acid secretion, be they PPIs or H2RAs. Included with these inhibitors, at least two antibiotics are given, either protein targeted (amoxicillin, clarithromycin) or DNA targeted (metronidazole). Another possibility is the addition of bismuth to triple therapy in a drug such as Pylera, quadruple therapy [36].

Protein targeted antibiotics require bacterial growth phase for their effect, amoxicillin binding to penicillin binding proteins and clarithromycin to 23S RNA resulting in eradication. There are only a few reports suggesting penicillin resistance but clarithromycin resistance is now >25% in the Western world due to a point A to G mutation [32]. Metronidazole must be reduced by NADPH nitroreductase (rdxA) for its activity and mutants lacking this enzyme are selected for by metronidazole based therapy for other diseases [37]. Resistance to metronidazole is also quite common, reaching 40% in some regions of the world [32]. The net effect of this resistance is that simple triple therapy is no longer adequate for routine treatment of infection by H. pylori [32]. This has resulted in variations on triple therapy such as sequential therapy or quadruple therapy with a PPI and a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate, metronidazole and tetracycline (Pylera) which produced 80% eradication compared to 55% on triple therapy [36].

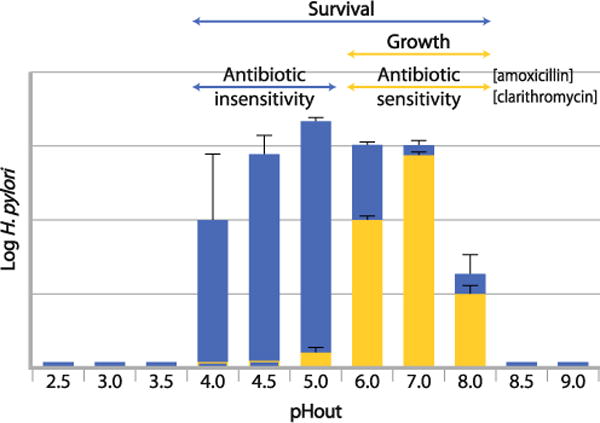

Whereas, the use of various antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori is readily understood, the rationale for the use of PPIs is less obvious as is the role of bismuth in quadruple therapy. Bismuth affects an as yet unknown process in the organism and is required in the stomach lumen. PPIs simply inhibit acid secretion although there are publications claiming a direct effect on the organism in vitro but at industrial doses [38]. An alternative explanation for the need for PPIs or even H2RA’s in eradication is the effect of inhibition of acid secretion on the growth properties of the organism. As stated above, the organism grows best between pH 6.0 and 8.0 in the absence of urea and between 4.0 and 6.0 in the presence of urea in buffered media. Figure 2 compares survival and antibiotic sensitivity of the organism at different medium pH in vitro in the absence and presence of urea. The bar graphs show that growth in the narrow range between 6 and 7 results in sensitivity to the growth dependent antibiotics, be they amoxicillin, clarithromycin or tetracycline. However between pH 4 and 6 there is little growth resulting in antibiotic resistance. With urea present, growth is extended to pH~4.

Fig. 2.

Survival and antibiotic sensitivity of H. pylori at different medium pH in vitro in the absence of urea. H. pylori grows at a narrow external pH range between 6 and 7 and are sensitive to the growth dependent antibiotics such as amoxicillin, clarithromycin or tetracycline (yellow bars). Although, H. pylori is able to survive at external pHs between 4 and 6 (blue bars) there is little growth decreasing the efficacy of the growth dependent antibiotics (blue bars)

With these data in mind, it is possible to postulate that the role of acid inhibition is to change intragastric pH so as to promote transition from stationary to log phase growth thus making the bacteria susceptible to the above antibiotics. When the infected gerbil is treated with a potent long lasting K+-competitive inhibitor of the H,K ATPase resulting in elevation of pH to close to neutrality, there is a large increase in expression of genes involved in protein synthesis, cell wall biosynthesis and cell division, providing evidence for the above rationale for the need for acid inhibition in H. pylori eradication therapy.

There have been some studies in Japan on patients who have mutations in Cyp2C19 resulting in slow metabolism of PPIs such as omeprazole or lansoprazole. Patients who are slow metabolizers homozygous for the Cyp2C19 mutation are more responsive to PPI therapy that those who are normal fast metabolizers. The greater degree of inhibition of acid secretion results in eradication of H. pylori with normal omeprazole dose and amoxicillin alone [39, 40]. These data suggest that more potent inhibition of acid secretion would result in better eradication data, particularly with amoxicillin.

New Targets for Eradication

Apart from the acid acclimation genes already discussed, there are many other genes essential for survival of H. pylori in the stomach, such as genes encoding for adhesion factors, iron and nickel homeostasis. However, no new therapeutic agents have emerged to date. Probiotics have been tested, but with varying efficacy as have vaccines [41•, 42]. Urease inhibitors, provided they are very selective, may appear in the future, as would inhibitors of UreI. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors provide another option and at least one laboratory is attempting to discover safe and selective inhibitors of the carbonic anhydrase of H. pylori [43].

Conclusions

It has been nearly 30 years since the discovery of H. pylori as the causative agent in gastric ulcer disease that resulted in a revolutionary change in the treatment of the disease. This gastric dwelling neutralophile is uniquely able to colonize an acidic niche through tight regulation of urea hydrolysis that results in periplasmic pH homeostasis enabling a constant proton motive force even in extreme acidity. Urease activity is the basis for diagnostic testing for H. pylori infection and much effort has been expended to use urease as an eradication target but has been unsuccessful. Eradication modalities using acid inhibitors and antibiotics have been decreasing in efficacy due in part to increasing antibiotic resistance and in part to poor acid control. As a better understanding the gastric biology of this pathogen develops, novel drug targets will be revealed.

Footnotes

Disclosure George Sachs has received grants and support in kind from NIH and USVA. David R. Scott has received grants from NIH and VA Merit Review; Yi Wen reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Contributor Information

George Sachs, Email: gsachs@ucla.edu, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Department of Physiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Bldg. 113, Rm. 324, 11301 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA.

David R. Scott, Email: dscott@ucla.edu, Department of Physiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Bldg. 113, Rm. 324, 11301 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA.

Yi Wen, Email: ywen@ucla.edu, Department of Physiology, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA; Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Bldg. 113, Rm. 324, 11301 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

- 1.Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, et al. Systematic review of the epidemiology of complicated peptic ulcer disease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion. 2011;84:102–13. doi: 10.1159/000323958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Genta RM, Graham DY. Comparison of biopsy sites for the histopathologic diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: a topographic study of H. pylori density and distribution. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:342–5. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgartner HK, Montrose MH. Regulated alkali secretion acts in tandem with unstirred layers to regulate mouse gastric surface pH. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:774–83. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksnas J, Phillipson M, Storm M, et al. Impaired mucus-bicarbonate barrier in Helicobacter pylori-infected mice. Am J Physiol. 2006;291:G396–403. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00017.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Wen Y, et al. Gene expression in vivo shows that Helicobacter pylori colonizes an acidic niche on the gastric surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:7235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702300104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young GM, Amid D, Miller VL. A bifunctional urease enhances survival of pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica and Morganella morganii at low pH. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6487–95. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6487-6495.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castanie-Cornet M-P, Penfound TA, Smith D, et al. Control of acid resistance in Escherichia coli. Volume. 1999;181:3525–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3525-3535.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster JW. Escherichia coli acid resistance: tales of an amateur acidophile. Nat Rev. 2004;2:898–907. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bauerfeind P, Garner R, Dunn BE, et al. Synthesis and activity of Helicobacter pylori urease and catalase at low pH. Gut. 1997;40:25–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Weeks DL, et al. Mechanisms of acid resistance due to the urease system of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:187–95. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weeks DL, Eskandari S, Scott DR, et al. A H+-gated urea channel: the link between Helicobacter pylori urease and gastric colonization. Science. 2000;287:482–5. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollenhauer-Rektorschek M, Hanauer G, Sachs G, et al. Expression of UreI is required for intragastric transit and colonization of gerbil gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori. Res Microbiol. 2002;153:659–66. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skouloubris S, Thiberge JM, Labigne A, et al. The Helicobacter pylori UreI protein is not involved in urease activity but is essential for bacterial survival in vivo. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4517–21. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4517-4521.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voland P, Weeks DL, Marcus EA, et al. Interactions among the seven Helicobacter pylori proteins encoded by the urease gene cluster. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:G96–G106. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00160.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong W, Sano K, Morimatsu S, et al. Medium pH-dependent redistribution of the urease of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 2003;52:211–6. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.05072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Wen Y, et al. Cytoplasmic histidine kinase (HP0244)-regulated assembly of urease with UreI, a channel for urea and its metabolites, CO2, NH3, and NH4(+), is necessary for acid survival of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:94–103. doi: 10.1128/JB.00848-09. This article shows that in addition to its role as a urea channel, UreI also serves as a membrane anchor for nickel induced activiation of urease and is capable of transporting CO2, NH3 and HH4+ aiding in periplasmic pH homeostasis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pflock M, Finsterer N, Joseph B, et al. Characterization of the ArsRS regulon of Helicobacter pylori, involved in acid adaptation. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3449–62. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3449-3462.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wen Y, Feng J, Scott DR, et al. The pH-responsive regulon of HP0244 (FlgS), the cytoplasmic histidine kinase of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:449–60. doi: 10.1128/JB.01219-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer-Rosberg K, Scott DR, Rex D, et al. The effect of environmental pH on the proton motive force of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:886–900. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee A, Dixon MF, Danon SJ, et al. Local acid production and Helicobacter pylori: a unifying hypothesis of gastroduodenal disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:461–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clyne M, Labigne A, Drumm B. Helicobacter pylori requires an acidic environment to survive in the presence of urea. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1669–73. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1669-1673.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Zanten SJ, Kolesnikow T, Leung V, et al. Gastric transitional zones, areas where Helicobacter treatment fails: results of a treatment trial using the Sydney strain mouse model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:2249–55. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2249-2255.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herrera V, Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15:971–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Selgrad M, Bornschein J, Rokkas T, et al. Clinical aspects of gastric cancer and Helicobacter pylori–screening, prevention, and treatment. Helicobacter. 2010;15(Suppl 1):40–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2010.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takayama S, Wakasugi T, Funahashi H, et al. Strategies for gastric cancer in the modern era. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:335–41. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i9.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi J, Kim CH, Kim D, et al. Aprospective evaluation of a new stool antigen test for detection of Helicobacter pylori, in comparison with histology, rapid urease test, 13C-urea breath test, and rerology. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leodolter A, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Von Arnim U, et al. Citric acid or orange juice for the 13C-urea breath test: the impact of pH and gastric emptying. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1057–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pantoflickova D, Scott DR, Sachs G, et al. 13C urea breath test (UBT) in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori: why does it work better with acid test meals? Gut. 2003;52:933–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimoyama T, Sawaya M, Ishiguro A, et al. Applicability of a rapid stool antigen test, using monoclonal antibody to catalase, for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:487–91. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Atherton JC, Blaser MJ. Coadaptation of Helicobacter pylori and humans: ancient history, modern implications. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2475–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI38605. This is an excellent review by the proponents of the controversial view that humans and H. pylori co-evoloved and that H. pylori is a commensal. The authors make a cogent argument that decreased rates of H. pylori infection correlate with a rise in a number of “modern diseases” and therefore H. pylori may be beneficial in preventing these diseases. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. 2007;56:772–81. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. Volume. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal disease: wake-up call? Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1819–22. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori colonization is inversely associated with childhood asthma. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:553–60. doi: 10.1086/590158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan VP, Wong BC. Helicobacter pylori and gastritis: untangling a complex relationship 27 years on. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(Suppl 1):42–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malfertheiner P, Bazzoli F, Delchier JC, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication with a capsule containing bismuth subcitrate potassium, metronidazole, and tetracycline given with omeprazole versus clarithromycin-based triple therapy: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:905–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han F, Liu S, Ho B, et al. Alterations in rdxA and frxA genes and their upstream regions in metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates. Res Microbiol. 2007;158:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakao M, Malfertheiner P. Growth inhibitory and bactericidal activities of lansoprazole compared with those of omeprazole and pantoprazole against Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 1998;3:21–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1998.08024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Furuta T, Shirai N, Ohashi K, et al. Therapeutic impact of CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics on proton pump inhibitor-based eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2003;25:131–43. doi: 10.1358/mf.2003.25.2.723687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furuta T, Sugimoto M, Shirai N, et al. CYP2C19 pharmacogenomics associated with therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-esophageal reflux diseases with a proton pump inhibitor. Pharmacogenomics. 2007;8:1199–210. doi: 10.2217/14622416.8.9.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41•.Czinn SJ, Blanchard T. Vaccinating against Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:133–40. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.1. This is an excellent review of the current status of vaccine development for H. pylori infection. The authors present the successes and pitfalls of animal and human vaccines and offer insight for the developement of efficacious vaccines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilhelm SM, Johnson JL, Kale-Pradhan PB. Treating bugs with bugs: the role of probiotics as adjunctive therapy for Helicobacter pylori (July/August) Ann Pharmacother. 2011 doi: 10.1345/aph.1Q104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishimori I, Minakuchi T, Morimoto K, et al. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: DNA cloning and inhibition studies of the alpha- carbonic anhydrase from Helicobacter pylori, a new target for developing sulfonamide and sulfamate gastric drugs. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2117–26. doi: 10.1021/jm0512600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scott DR, Marcus EA, Weeks DL, et al. Expression of the Helicobacter pylori ureI gene is required for acidic pH activation of cytoplasmic urease. Infect Immun. 2000;68:470–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.470-477.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen Y, Marcus EA, Matrubutham U, et al. Acid-adaptive genes of Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5921–39. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.10.5921-5939.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]