Summary

Collective cell migration is a highly regulated morphogenetic movement during embryonic development and cancer invasion that involves precise orchestration and integration of cell autonomous mechanisms and environmental signals. Coordinated lateral line primordium migration is controlled by the regulation of chemokine receptors via compartmentalized Wnt/β-catenin and Fgf signaling. Analysis of mutations in two exostosin glycosyltransferase genes (extl3, ext2) revealed that loss of Heparan Sulfate chains results in a failure of collective cell migration due to enhanced Fgf ligand diffusion and loss of Fgf signal transduction. Consequently, Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated ectopically resulting in the subsequent loss of the chemokine receptor cxcr7b. Disruption of HSPG function induces extensive, random filopodia formation, demonstrating that HSPGs are involved in maintaining cell polarity in collectively migrating cells. HSPGs themselves are regulated by the Wnt/β-catenin and Fgf pathways and are therefore integral components of the regulatory network coordinating collective cell migration with organ specification and morphogenesis.

Introduction

Collective cell migration is a fundamental process guiding many aspects of morphogenesis in embryonic development and its misregulation is associated with metastatic cancer (Aman and Piotrowski, 2011; Ilina and Friedl, 2009). Yet, our understanding of the molecular mechanisms controlling the migration of groups of cells and how they are integrated is limited. Studies of border cell migration in Drosophila and the zebrafish lateral line system have begun to provide mechanistic insight into the nature of collective cell migration (Aman and Piotrowski, 2009; Montell et al., 2012; Rorth, 2012).

The lateral line (LL) sensory system allows fish and amphibians to sense their environment by detecting water motion (Mogdans and Bleckmann, 2012). The zebrafish posterior LL develops from a migrating placode/primordium (referred from now on as prim) that migrates as a collective cluster of cells from posterior of the ear toward the tail tip (Chitnis et al., 2012). The prim periodically deposits cell clusters that differentiate into sense organs called neuromasts (Sarrazin et al., 2010). The leading region of the prim consists of a group of unpatterned cells, while the trailing region is organized into rosette shaped prosensory organs (Lecaudey et al., 2008; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008).

Recent work has provided a detailed understanding of the major signaling pathways that orchestrate collective cell migration and sensory organ formation (Figure S1) (Aman et al., 2011; Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Lecaudey et al., 2008; Li et al., 2004; Matsuda et al., 2013; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). The prim expresses the chemokine receptors cxcr4b and cxcr7b, and migrates along a stripe of Cxcl12a ligand produced by muscle cells along the horizontal myoseptum. Mutations in either chemokine receptor or ligand cause loss of directional migration and random tumbling of primordium cells (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008; Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007; David et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004). Moreover, LL development is tightly regulated by Wnt/β-catenin (referred from now on as Wnt) and Fgf feedback interactions, which lead to activation of these pathways in mutually exclusive domains. Wnt signaling in the leading region induces Fgf ligand expression that activates signaling in the trailing region of the primordium. Wnt and Fgf signaling antagonize each other by inducing the expression of the Fgf inhibitor sef and the Wnt inhibitor dkk1b, respectively. This ensures the segregation of the Wnt and Fgf activation domains to adjacent territories (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). However, the mechanisms regulating ligand distribution and their effects on activation of signaling cascades to coordinate cell migration remain to be elucidated.

Extracellular matrix proteins, such as Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans (HSPGs) bind and regulate the activity of signaling molecules (Sarrazin et al., 2011). HSPGs possess chains of the sulfated glycosaminoglycan heparan sulfate (HS) that bind signaling molecules in the extracellular matrix. Previous studies suggest three main HSPGs functions. First, they act as coreceptors for the Wnt, FGF, Hh and BMP pathways (Kreuger et al., 2004; Lin and Perrimon, 2000; Shiau et al., 2010; Yan and Lin, 2007). Second, HSPGs alter the ability of signaling molecules to move from cell to cell (Yan and Lin, 2009; Yu et al., 2009). Third, HSPGs can be cleaved or shed from the cell membrane, changing ligand concentration and availability to adjacent cells (Giraldez et al., 2002; Manon-Jensen et al., 2010). Thus, HSPGs are important for signaling activation and potentiation of morphogen gradients. Disruption of HSPGs leads to defects in gastrulation, convergent extension and axon sorting (Clement et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2004; Poulain and Chien, 2013; Topczewski et al., 2001). However, the mechanisms through which HSPGs regulate signaling pathways or how HSPGs alterations may result in developmental abnormalities are not well defined.

The Exostosin (EXT) family of glycosyltransferases synthesizes HS chains (Busse et al., 2007). Mutations in human EXT genes cause Multiple Hereditary Osteochondroma (MHO), an inherited skeletal disorder, and are associated with leukemia, breast, liver and colorectal cancer (Busse-Wicher et al., 2013). EXT genes are conserved and essential for metazoan development, as mutations in their Drosophila orthologs cause defects in morphogen gradients (Takei et al., 2004). Zebrafish ext2 and extl3 genes are ubiquitously expressed and mutants exhibit defects in axon sorting, jaw and fin development (Clement et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2004; Norton et al., 2005; Poulain and Chien, 2013).

In this study, analyses of ext2 and extl3 mutants as well as embryos treated with the sulfation inhibitor Sodium Chlorate (NaClO3) (Safaiyan et al., 1999) revealed that HSPGs are essential components of the regulatory network modulating collective cell migration. HS are required for Fgf signaling activation and restricted diffusion of Fgf ligand, which impacts the proper maintenance and localization of the Wnt and chemokine receptor activity domains. In addition, HS are crucial for cell polarity in the collectively migrating prim and their loss leads to abundant ectopic filopodia. Thus, HSPGs play critical roles during the morphogenesis of the LL by controlling the interplay between signaling pathway networks that underlies the correct patterning and migration of the primordium.

Results

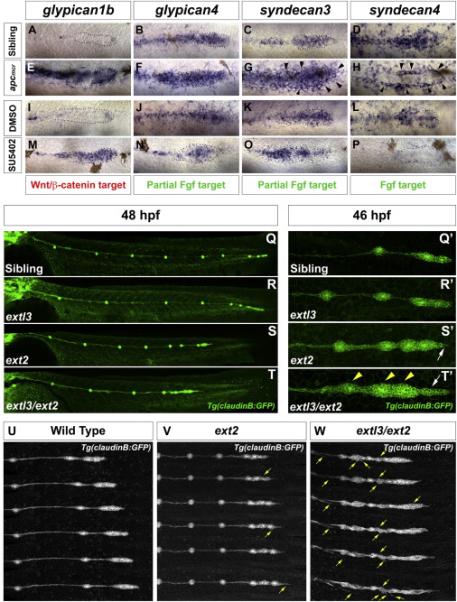

Four HSPGs are expressed in discrete domains in the primordium

To understand how Wnt and Fgf ligands distribute along the prim we investigated candidate molecules that may participate in the regulation of signaling molecules. HSPGs are strong candidates based on their ability to modulate Wnt, Fgf, BMP and Hh signaling regulation. Zebrafish possess fourteen HSPGs: one perlecan, three syndecans and ten glypicans (www.ZFIN.org). In addition to the previously described gpc1a (Gupta and Brand, 2013), two glypicans and two syndecans are expressed in specific domains of a 32 hours post fertilization (hpf) primordium, as well as in neuromasts and interneuromast cells (Figure 1A-1D; data not shown). glypican1b (gpc1b) is restricted to a few cells at the leading edge (Figure 1A). glypican4 (gpc4) is expressed in the posterior 2/3 of the prim overlapping with the Fgf domain. (Figure 1B). syndecan3 (sdc3) expression is evenly distributed with slightly higher expression in central cells of the prim (Figure 1C) and syndecan4 (sdc4) expression is found predominantly in the next-to-be deposited rosette in the trailing region of the prim (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Loss of HSPGs results in LL prim migration and patterning defects.

gpc1b expression in (A) wild type (WT), (E) apcmcr, (I) DMSO and (M) SU5402 treated. gpc4 and sdc3 expression in (B-C) WT, (F-G) apcmcr, (J-K) DMSO and (N-O) SU5402 treated embryos. sdc4 expression in (D) WT, (H) apcmcr, (L) DMSO and (P) SU5402. Black arrowheads (G,H) point at ectopic halo of sdc3 and sdc4. (Q-R) WT and extl3 mutant prim has reached the tail tip by 48 hpf. (S-T) ext2 and extl3/ext2 prim fails to complete migration. (Q’-T’) Magnification of prim at 46 hpf. (Q’-R’) WT and extl3 mutant prim shows a normal morphology. ext2 mutant prim possesses a pointed tip (S’, white arrow). (T’) extl3/ext2 mutant prim shows severe morphological defects. The leading edge elongates (white arrow) and rosettes are closely spaced (yellow arrowheads). Still images of time lapse movies: WT (U), ext2 (V) and extl3/ext2 mutant prim (W). (V,W) Yellow arrows point at ectopic filopodia.

The restricted expression domains of these genes suggested that they could be part of the Wnt and Fgf signaling feedback loop. To test if these pathways control the expression of HSPGs in the prim, we analyzed the expression of HSPGs in apcmcr mutants, where Wnt and Fgf signaling is upregulated (Figure 1E-1H) and in embryos in which Fgf signaling is inhibited leading to expansion of the Wnt signaling domain (Figure 1I-1P). gpc1b is a Wnt target as it expands in apcmcr mutants and after Fgf signaling inhibition (Figure 1E, 1I and 1M). apcmcr mutants also show upregulation of gpc4 (Figure 1F). However, upon inhibition of Fgf, gpc4 expression is partially downregulated, suggesting that it is partially dependent on Fgf signaling (Figure 1J and 1N). Similarly, sdc3 is significantly upregulated in apcmcr mutants, even in cells surrounding the prim (Figure 1G, arrows). However, after Fgf inhibition sdc3 expression is mostly restricted to the central cells (Figure 1K and 1O) suggesting that sdc3 is induced by Wnt but also depends on Fgf signaling. Finally, sdc4 is clearly inhibited by Wnt signaling within the primordium, but activated in the surrounding cells (Figure 1H, arrows). Interestingly, Fgf inhibition turns off sdc4 completely demonstrating that sdc4 is a Fgf target inhibited by Wnt signaling (Figure 1L and 1P). These results demonstrate that the four primordium-expressed HSPGs are part of a feedback loop between Wnt and Fgf signaling. Hence, they may play a role in modulating signaling interactions and regulatory networks that orchestrate proper morphogenesis of the LL.

Loss of HS in ext2 and extl3 mutants results in severe LL defects

To determine the function of HSPGs in LL development, we analyzed ext2/dackel and extl3/boxer mutants in which the function of all HSPGs is affected. Offspring of extl3 and ext2 parents were crossed with the Tg(claudinB:GFP) line to analyze LL phenotypes. extl3 mutants do not possess an evident LL phenotype at 48 hpf and the prim reaches the tail tip (Figure 1Q-1R’). In contrast, ext2 mutant prim stalls at the level of somite 20 (10/10 mutants), where they deposit closely spaced neuromasts, likely caused by a reduction in migration speed before stalling (Figure 1S, Movie S1). ext2 prim is characterized by a pointed leading edge and contains an average of two rosettes at the time of stalling (1.56 ±0.504, n=31 - Figure 1S’ and 1U-1V). Because of the mild LL phenotypes of extl3 and ext2 mutants and their closely related function in the post-translational control of HS synthesis, these two genes may possess overlapping functions. We generated double mutants between extl3 and ext2, termed extl3/ext2 that show a more severe phenotype than either single mutant. Immunohistochemistry against HS with 3G10 demonstrates that HS are enriched in prim cell membranes and cells surrounding the prim (Figure S2A, arrows). In extl3/ext2 mutants, 3G10 is almost undetectable indicating these embryos lack all/most HS chains (Figure S2B). extl3/ext2 mutant prim stalls earlier than ext2 mutants and the prim morphology is more severely affected (Figure 1T, 1T’ and 1W). extl3/ext2 prim exhibits an elongated tip region evident at 32 hpf (Movie S2). Rosettes are visible in 46 hpf primordia, however, the prim appears bigger due to the close deposition of neuromasts connected by clumps of interneuromast cells (Figure 1T’, arrows). Although ext2 and extl3/ext2 primordia stalls, time lapse movies show that the directionality of the leading tip cells is not lost and that they keep extending towards the tail (Figure 1U-1W; Movie S3). Interestingly, starting at around 50 hpf extl3/ext2 mutant LL cells extend dynamic filopodia in all directions. Interneuromast cells detach and extend ectopic leading tips that orient away from the LL (Figure 1W, arrows; Movie S4). At 5 dpf extl3/ext2 mutant neuromasts collapse and rosettes are nearly indistinguishable (Figure S2C-S2F). The striking phenotypes of extl3/ext2 mutants clearly demonstrate that HS are crucial for LL development.

The Wnt pathway is ectopically activated in the absence of HS

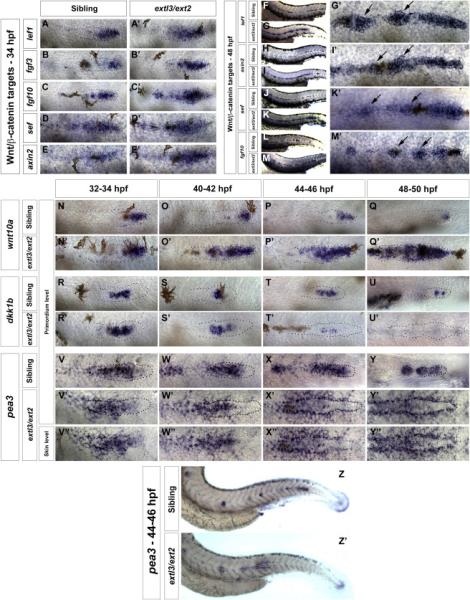

extl3/ext2 mutant prim stalls in a manner analogous to apcmcr prim (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). Therefore, we investigated whether HSPGs affect Wnt signaling. In situ analyses in 34 hpf extl3/ext2 mutants demonstrate that Wnt target expression, such as lef1, fgf3, fgf10, sef and axin2 expands into the trailing region (Figure 2A-2E’) and at 48 hpf are expressed in the entire trailing region, as well as in clusters of deposited cells (Figure 2F-2M’- arrows in Figure 2G’, 2I’, 2K’ and 2M’).

Figure 2. The Wnt/β-catenin pathway is ectopically activated in extl3/ext2 mutants.

(A-M’) In extl3/ext2 mutants Wnt/β-catenin target genes expand progressively between 34-48 hpf. Sibling prim migration has finished by 48 hpf (F,H,J,L). (G, I, K, M) In extl3/ext2 mutants the prim stalls and lef1, axin2, sef and the fgf10 are upregulated. (G’, I’, K’ and M’) Magnified views of extl3/ext2 mutant prim. Black arrows: Wnt/β-catenin target expression in interneuromast cells. (N-U’) Time course of the Wnt/β-catenin target wnt10a and inhibitor dkk1b. wnt10a upregulation correlates with the downregulation of dkk1b. (O-O’, S-S’) Mild downregulation of dkk1b corresponds with the expansion of wnt10a at 40-42 hpf. (P-P’, T-T’) By 44-46 hpf, wnt10a expands along the prim and dkk1b expression is almost lost. (Q-Q’, U-U’) By 48-50 hpf dkk1b expression is entirely reduced resulting in complete expansion of wnt10a. (V-Y’) The Fgf target pea3 is gradually lost in the prim but progressively activated in surrounding cells (V”-Y”). (Z-Z’) Lower magnification images of the 44-46 hpf embryos in X, X’ and X”.

A time course of the Wnt target wnt10a revealed that Wnt signaling is progressively and ectopically activated in the trailing region of extl3/ext2 prim (Figure 2N-2Q’). We examined if the expansion of wnt10a correlated with the gradual decrease of Fgf targets, such as the Wnt inhibitor dkk1b. The wnt10a and dkk1b time course (Figure 2N-2U’) demonstrates that at 40-42 hpf the wnt10a domain begins to expand, whereas dkk1b expression decreases (Figure 2O-2O’, 2S-2S’). At 48 hpf wnt10a expands along the entire length of the primordium, while dkk1b is completely downregulated (Figure 2Q-2Q’, 2U-2U’). Consistent with the ectopic expression of wnt10a, by 3 dpf the Wnt target genes lef1 and fgf3 are expressed along the entire LL (Figure S2G-2H’).

The gradual and late onset gene expression changes in extl3/ext2 mutants correlate with the start of prim migration defects at 44 hpf. Cells in the prim begin to tumble, the prim stalls, and rosettes and deposited neuromasts collapse.

Fgf signal transduction is strongly reduced in extl3/ext2 prim but activated in surrounding cells

The Fgf target dkk1b restricts Wnt signaling, and Wnt signaling in turn induces Fgf signaling (Aman and Piotrowski 2008). Therefore, the Fgf mediated downregulation of dkk1b in extl3/ext2 prim suggests that loss of Fgf signaling could be the underlying cause of ectopic Wnt activation. To test this possibility, we analyzed the expression of additional Fgf pathway members in extl3/ext2 prim. The Wnt targets fgf3 and fgf10a are expressed (Figure 2B-2C’, 2L-2M’), however, the presence of Fgf ligands does not reveal if the Fgf pathway is activated. We tested the expression of the Fgf target fgfr1 and observed that fgfr1 is increasingly downregulated (Figure S2I-S2K’). A time course analysis of the Fgf target pea3 revealed that its diminishing expression in the prim mirrors the progressive disappearance of dkk1b (Figure 2V-2Y’). Images of different focal planes illustrate that by 44-46 hpf pea3 is severely reduced in prim cells but increasingly upregulated in cells surrounding the primordium, forming a halo (Figure 2V’’-2Y’’, 2Z-2Z’, S3D-S3E’’). The Fgfr blocker SU5402 inhibits the expression of the ectopic pea3 halo confirming that it is Fgf dependent (Figure S3A-S3B’). Therefore, in contrast to prim cells, surrounding cells do not require HS for Fgf signal transduction, possibly because these cells express a HS-independent Fgf receptor and the dependence of Fgf signaling on HS chains is primordium-specific.

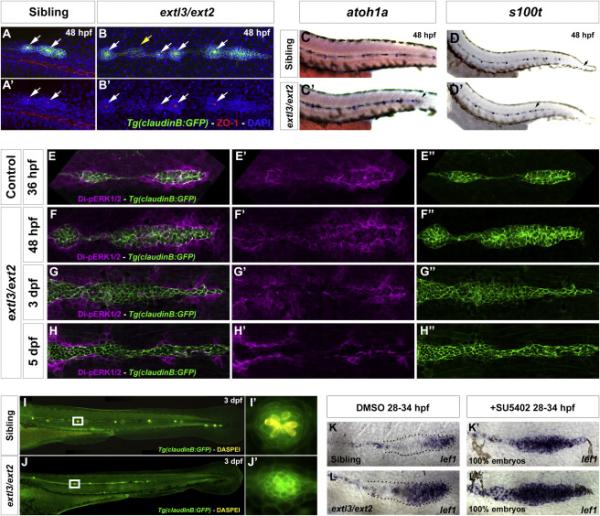

Fgf signaling is essential for rosette-shaped proneuromast formation within the primordium, as well as maintenance of neuromasts (Lecaudey et al., 2008; Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008). However, rosettes are still present in 48 hpf extl3/ext2 prim, as revealed by ZO-1 staining and the hair cell precursor markers atoh1a and s100t (Figure 3A-3B’, 3C-3D’). Therefore, low levels of Fgf signaling may still take place in the mutants. Unfortunately, quantitative measurements of Fgf signal activation within prim cells is challenging, as LL cells would have to be isolated by fluorescent activated cell sorting and available transgenic lines also express GFP in the epidermis at this stage.

Figure 3. Fgf signal transduction is progressively lost in extl3/ext2 mutant prim.

(A-B’) ZO-1 staining reveals apical constrictions (white arrows) in 48 hpf extl3/ext2 neuromasts and prim rosettes but not in interneuromast clumps (yellow arrow). (C-D’) LL hair cells precursors are present in 48 hpf extl3/ext2 mutants as evidenced by atoh1a and s100t expression. (C,D,D’) Black arrows indicate prim position. (E-H”) Dp-ERK staining reveals remaining low levels of Fgf signaling in the 48 hpf primordium. Dp-ERK is progressively downregulated as rosettes collapse (E”-H”). By 5 dpf no protein remains inside the prim (H’). (I-J’) By 3 dpf most of the formed hair cells die inside the collapsing neuromast. (I’, J’) Neuromasts outlined in white boxes in I, J. (K-L’) Inhibition of Fgf signaling accelerates the onset of the extl3/ext2 phenotype. extl3/ext2 mutants and their siblings treated with SU5402 from 28 to 34 hpf show complete upregulation of the Wnt target lef1.

Indeed, MAP kinase-signaling pathway activity is still detectable in 48 hpf extl3/ext2 mutant prim by Di-pERK1/2 (dp-ERK) staining, even though pea3 is already reduced at this stage (Figures 3E-3F” and 2Y-2Y'). By 3 dpf, extl3/ext2 mutant neuromasts are elongated and lose their rosette shape as well as hair cells (Figure 3G-3G” and 3I-3J) like embryos with complete loss of Fgf signaling (Lush and Piotrowski, 2014). The loss of rosettes correlates with the downregulation of dp-ERK at this stage (Figure 3G’). At 5 dpf, GFP-positive LL cells are dp-ERK-negative and rosettes are not distinguishable anymore (Figure 3H-3H”). Dp-ERK is also expressed in a halo surrounding the prim in wildtype (WT) (Harding and Nechiporuk, 2012) and extl3/ext2 mutant larvae (Figure 3E-3H’) but becomes increasingly upregulated as extl3/ext2 mutants mature. However, the level of Fgf signaling in surrounding cells is lower in WT embryos, as pea3, which requires higher levels of Fgf signaling, does not form a halo (Figure 2Z-2Z’).

extl3/ext2 mutants show a late onset migration phenotype at around 44 hpf correlating with the loss of Fgf signaling. We wondered if the delayed onset of the phenotype is caused by the remaining, although decreasing Fgf signaling levels. We reasoned that if this hypothesis was correct, depletion of Fgf signaling in extl3/ext2 mutant prim would lead to an earlier onset of the phenotype. Indeed, the Wnt target lef1 is expressed throughout the entire prim in 100% of Fgf signaling depleted embryos, demonstrating that Wnt signaling only expands once Fgf signaling decreases (Figure 3K-3L’).

These analyses show that HS are crucial for Fgf signaling regulation during collective cell migration. Since the activation of the Fgf signaling pathway fails in extl3/ext2 mutant prim despite normal Fgf ligand production, we conclude that the loss of HS directly affects Fgf signaling, which in turn leads to the expansion of Wnt signaling. In contrast, the finding that Wnt signaling is ectopically activated in extl3/ext2 mutant prim with severely reduced HS chainssuggests that HS are likely not necessary for Wnt signal activation.

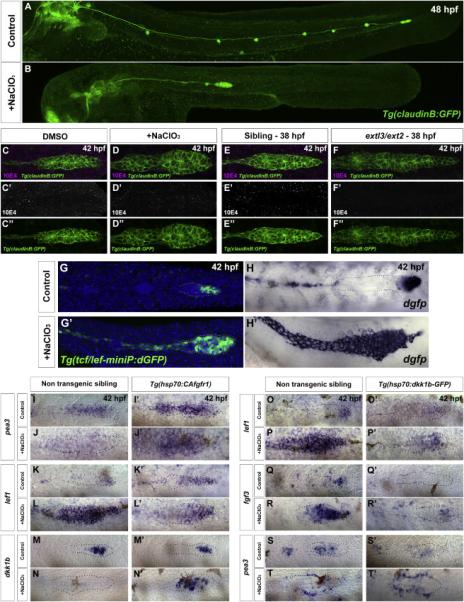

Pharmacological disruption of HSPGs phenocopies extl3/ext2 mutants

We wised to explore chemical inhibitors that affect HS function in a manner similar to extl3/ext2 mutants. Sodium Chlorate (NaClO3) inhibits the formation of the sulfation donor 3’-phosphoadenosine 5’-phosphosulfate (PAPS). Exposing cell cultures to NaClO3 leads primarily to the loss of 2-O and 6-O sulfations, affecting the ability of HS to bind signaling molecules (Safaiyan et al., 1999). NaClO3-treatment phenocopies the morphological phenotypes of extl3/ext2 mutants, as prim cells tumble and the prim stalls (Figure 4A-4B; Movie S5). 3G10 staining shows that HS chains are still present after NaClO3 treatment (Figure S3G-S3H”). Thus, to determine which HS disaccharide units are affected in NaClO3 -treated larvae, we performed a disaccharide analysis. We observed a 8-fold increase in unsulfated HS (Table S1), where 2-O sulfations in combination with N-sulfations, as well as 6-O sulfations were reduced by 55%, similarly to extl3/ext2 mutants (Lee et al., 2004). Likewise, N-sulfated glucosamine residues stained by 10E4 showed downregulation in NaClO3-treated prim (Figure 4C-4F”).

Figure 4. NaClO3-treatment phenocopies extl3/ext2 mutants causing loss of Fgf signaling and resulting in the expansion of the Wnt domain.

(A-B) In NaClO3-treated embryos the prim stalls. (C-D”) NaClO3-treated embryos show downregulation of HS levels by 10E4 antibody staining. (E-F”) extl3/ext2 mutants show a similar loss of HS. (G-H’) NaClO3-treated Wnt reporter line embryos show expansion of the Wnt domain in the primordium, evidenced by destabilized GFP (dGFP) expression and dgfp in situ hybridization. (I-J’) The Fgf target pea3 is restored in NaClO3-treated prim after CAfgfr1 induction. (K-L’) Restored Fgf signaling restricts the expression of the Wnt target lef1 back to the leading region. (M-N’) The restored restriction correlates with the activation of dkk1b after Fgf pathway activation. (O-T’) Wnt is restricted after NaClO3-treatment by inducing Dkk1b expression in the Tg(hsp70:dkk1b-GFP) line. (O-P’ and Q-R’) In the absence of HS, Dkk1b induction is sufficient to restrict the Wnt targets lef1 and fgf3 back to the leading region but not to restore Fgf signaling in the trailing region of the prim (ST’). pea3 is still only expressed in cells surrounding the prim (T’).

To determine if the migration phenotype in treated larvae is caused by ectopic Wnt signaling, we treated Tg(tcf/lef-miniP:dGFP) Wnt reporter embryos with NaClO3 (Shimizu et al., 2012). Indeed, NaClO3 drastically expands the Wnt domain (Figure 4G-4H’). More importantly, the changes in Wnt and Fgf signaling phenocopy extl3/ext2 mutants, in which the Fgf targets pea3 and dkk1b are increasingly downregulated, while the Wnt target lef1 is correspondingly upregulated (Figure S3I-S3W’). Similarly to ext mutants, NaClO3-treated embryos develop an ectopic Fgf-dependent pea3 halo outside the prim cells (Figure S3C-S3C’, S3F-S3F”). Therefore, NaClO3 treatment represents a powerful pharmacological tool to analyze the role of HS in a temporally inducible manner.

Fgfr1 requires HS to transduce the Fgf signal in the LL primordium

In extl3/ext2 mutant prim Fgf signaling does not occur in the presence of Fgf ligands. HSPGs are also important for the activation of Fgf signaling in Drosophila, Xenopus and zebrafish. Hence, we sought to determine whether Fgf receptors are functional in the absence of HS. We treated Tg(hsp70:CAfgfR1) embryos with NaClO3 and heat shocked them to activate Fgfr1 in the absence of HS (Figure 4I-4N’). As expected, NaClO3-treated control embryos lose pea3 expression in the prim (Figure 4I-4J). However, when we activate Fgfr1, expression of pea3 is rescued within the prim (Figure 4J-4J’). Moreover, expression of lef1 is again confined to the leading region (Figure 4L-4L’). Finally, expression of dkk1b is also re-established (Figure 4N-4N’). These results clearly demonstrate the requirement of HS for proper Fgfr1 function in the primordium, potentially acting as coreceptors. The ability to rescue Fgf signaling activation in NaClO3-treated embryos also reduces concerns that this chemical may have non-specific effects in the primordium.

Expansion of the Wnt domain in extl3/ext2 mutants is a result of dkk1b loss

Wnt is markedly upregulated along the entire prim by 48 hpf. This upregulation correlates with the gradual downregulation of dkk1b expression in HS-depleted embryos (Figure 2R-2U' and S3V-S3V’). Therefore, we tested if ectopic activation of Dkk1b in NaClO3-treated Tg(hsp70:dkk1-GFP) embryos is sufficient to restrict Wnt signaling to the leading domain (Figure 4O-4T’). lef1 expression expands along the entire prim in NaClO3-treated embryos, yet is restricted to the leading region in control embryos (Figure 4O-4P). Induction of Dkk1b leads to complete Wnt abrogation in control embryos (Figure 4O’). However, in NaClO3-treated embryos, Dkk1b induction drastically downregulates lef1 and restricts its expression back to the leading region of the prim (Figure 4P’). We observed a similar effect on the Wnt target fgf3 (Figure 4R-4R’). In contrast, pea3 expression is not rescued after Dkk1b induction in NaClO3-treated embryos, affirming the requirement of HS for Fgf signal transduction within prim cells (Figure 4T-4T’). Interestingly, the halo of ectopic pea3 expression persists in these embryos even when fgf ligands are not abundantly expressed anymore (Figure 4R-4R’ and 4T-4T’). This shows that the halo does not form because of an overabundance of Fgf ligands but because HS are required to restrict Fgf ligands to prim cells.

These results demonstrate that Wnt expansion in HS-depleted embryos is a result of the loss of dkk1b due to failed induction of Fgf signaling. HS are essential for the maintenance of the boundary between Wnt and Fgf signaling domains in the primordium, and without the proper posttranslational modifications of the HSPG core protein, Fgf signal transduction is lost, even in the presence of ligands and receptors.

Prim stalling in extl3/ext2 mutants corresponds with temporal changes in chemokine receptor expression

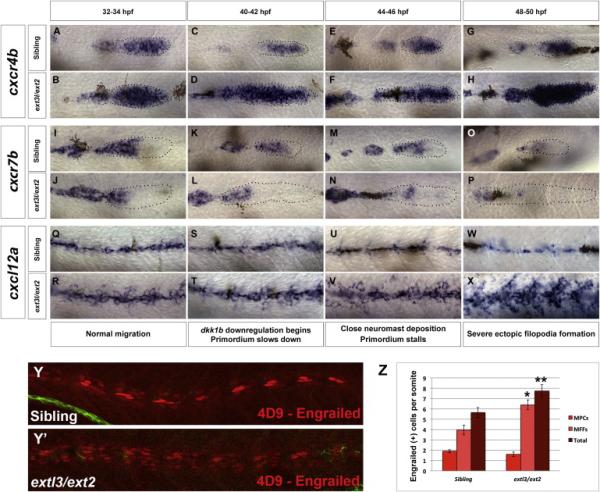

Chemokine signaling is vital for proper prim migration (Aman et al., 2011). Cxcr7b sequesters Cxcl12a in the trailing region of the primordium, which generates a Cxcl12a gradient that provides a directional guidance cue for prim cells (Dona et al., 2013; Venkiteswaran et al., 2013). We performed a time course of cxcr4b and cxcr7b expression to monitor changes in chemokine expression associated with prim stalling. cxcr4b is upregulated in extl3/ext2 prim at 32 hpf and increases over time (Figure 5A-5H). In contrast, cxcr7b expression is only downregulated at 44 hpf and disappears by 50 hpf (Figure 5I-5P). The loss of cxcr7b causes a decrease in migration speed. Hence, in contrast to WT prim, mutant prim is delayed (Figure 1T).

Figure 5. Chemokine receptor expression correlates with prim stalling in extl3/ext2 mutants.

(A-H) cxcr4b time course from 32 to 50 hpf of siblings and extl3/ext2 mutants. cxcr4b is upregulated at 32-34 hpf and increases as the embryo develops. (I-P) cxcr7b is expressed normally between 32 and 42 hpf in extl3/ext2 mutants but becomes downregulated at 44 hpf until it is absent by 50 hpf. These expression changes correlate with the expansion of Wnt signaling (Figure 2) and slowing down and stalling of the primordium. (Q-X) cxcl12a time course shows that, despite the upregulation of cxcl12a at 32 hpf, the prim continues to migrate until cxcr7b is downregulated by 44-46 hpf (M-P). cxcl12a upregulation continues as the extl3/ext2 phenotype becomes severe by 50 hpf (W-X). (Y-Y’, Z) extl3/ext2 mutants possess more Engrailed (4D9) positive medial fast muscle fibers along the trunk.

Prim migration is also influenced by Cxcl12a expression in a subset of Engrailed-positive muscle pioneer cells (MPCs) and medial fast muscle fibers (MFFs) along the myoseptum that form a track along which the prim migrates (Dambly-Chaudiere et al., 2007; David et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004; Valentin et al., 2007). These muscle cells form in response to Shh secreted by the notochord, whereas their development is restricted to the midline by Bmp repressing signals from the somites (Maurya et al., 2011). cxcl12a is upregulated along the myoseptum in extl3/ext2 mutants (Figures 5Q-5X) in which the number of cxcl12a secreting MPCs does not change but the MFFs are increased in response to higher Shh signaling (Figure 5Y-5Z and Figure S4A-S4D’).

Interestingly, extl3/ext2 mutants show upregulation of cxcr4b and cxcl12a at 32 hpf (Figure 5A-5B and Figure 5Q-5R) yet the prim migrates for twelve more hours (Figure 5E-5F and Figure 5U-5V) and only slows down once cxcr7b is downregulated at 44 hpf (Figure 5M-5N). This delayed phenotype implies that simultaneous upregulation of cxcr4b and cxcl12a in the presence of cxcr7b allows for the temporary maintenance of the Cxcl12a gradient required for prim migration. As Wnt inhibits the expression of cxcr7b in the primordium, the changes in cxcr7b expression correlate with Wnt signaling expansion (Figure 2Q-2Q’ and S4G-J;) (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008). The reduction of cxcr7b expression marks the time point when prim cells begin to tumble and stall suggesting that the loss of directional migration is likely caused by primordium-autonomous defects in chemokine receptor expression.

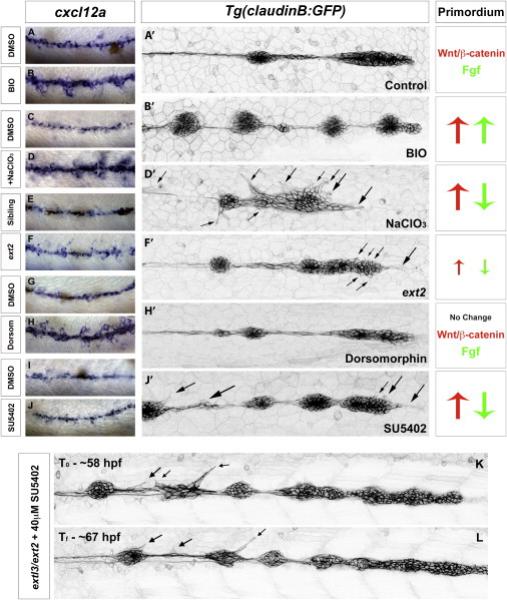

Loss of Fgf signaling and HS leads to random, dynamic filopodia formation

In extl3/ext2 mutant LL cells extend ectopic, dynamic filopodia that reach over long distances in different directions (Movie S4 and S6, Figure 1W). The severity of this phenotype correlates temporally with the highest increase in ectopic cxcl12a suggesting that cxcl12a in the environment might contribute to ectopic filopodia formation. To examine whether cxcl12a overexpression is sufficient to induce ectopic filopodia, we analyzed embryos in which diverse pathway manipulations caused ectopic cxcl12a expression. cxcl12a is upregulated when the Wnt pathway is activated after treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor BIO (Figure 6A-6B). cxcl12a is also upregulated along the myoseptum of embryos with compromised HS, such as NaClO3-treated, extl3/ext2 and ext2 mutants (Figure 5W-5X, 6C-6F) and after inhibition of Bmp signaling with Dorsomorphin (Figure 6G-6H). However, we only find ectopic filopodia formation in conditions in which the Fgf signaling pathway is also downregulated in the primordium, irrespective of cxcl12a upregulation (Figure 6D’, F’, 6I-6J’). For example, in BIO-treated embryos in which Fgf signaling is active, cxcl12a is strongly expressed, however no ectopic filopodia forms (Figure 6B’). Likewise, when we overexpress cxcl12a in Tg(hsp70:sdf1a) embryos, we only observe a few short ectopic filopodia in the most leading prim cells (Figure S4E-S4F and Movie S7). We therefore conclude that ectopic cxcl12a expression is not sufficient to induce loss of cell polarity and aberrant filopodia formation to the degree observed in extl3/ext2 mutants.

Figure 6. Loss of Fgf signaling and HS function leads to random, dynamic filopodia formation.

(A-B’) DMSO or BIO-treated Tg(claudinB:GFP) embryos show upregulation of cxcl12a but no evidence of ectopic filopodia formation. BIO-treatment leads to the upregulation of the Wnt and Fgf pathways in the primordium. (C-D’) In NaClO3-treated Tg(claudinB:GFP) embryos cxcl12a is upregulated inducing severe filopodia formation along all LL cells (D’). Similar to extl3/ext2 mutants, these embryos show upregulation of Wnt and loss of Fgf signaling. (E-F’) cxcl12a is only slightly upregulated in ext2 mutants. Mild ectopic filopodia are observed in the most anterior region of the prim by time lapse recording (F’, Movie S3). 48 hpf ext2 mutants show only partial Wnt upregulation and Fgf signaling downregulation (data not shown). (G-H’) Bmp signaling inhibition with Dorsomorphin induces Shh, leading to an increase in Engrailed-positive and cxcl12a-expressing muscle cells. Bmp inhibition does not alter prim migration or signaling, but induces the upregulation of cxcl12a. (I-J’) Inhibition of Fgf signaling by SU5402 does not cause upregulation of cxcl12a but formation of ectopic filopodia in LL cells (J’). Wnt is upregulated as a result of Fgf inhibition. (K-L) Inhibition of Fgf signaling in extl3/ext2 mutants does not eliminate ectopic protrusions. Black arrows point at ectopic filopodia.

Loss of Fgf signaling also causes ectopic filopodia, but more mildly than in extl3/ext2 mutants or NaClO3-treated embryos (Figure 6J’). We attribute this difference to the fact that loss of Fgf signaling only affects some HSPGs, whereas all HSPGs are affected in ext mutants.

These experiments suggest that loss of Fgf signaling affects filopodia formation possibly via the loss of some HSPGs. However, a recent study demonstrated that cells in the trailing region of the prim migrate towards a source of Fgf ligands independently of Chemokine signaling (Dalle Nogare et al., 2014). In extl3/ext2 mutants Fgf-dependent dp-ERK is expressed at high levels in cells surrounding the prim and increases as the mutants develop (Figure 3E'-3H'; S6H-S6K’). Therefore, we wondered if the increase in Fgf signaling in surrounding cells attracts filopodia. We tested this hypothesis by blocking Fgf signaling in extl3/ext2 mutants. In treated embryos, dp-ERK is completely downregulated, however LL cells still show active, ectopic protrusions (Figure 6K-6L and S5A-S5D”; Movie S8). We also overexpressed Fgf signaling in Tg(hsp70:CAfgfr1) and Fgf signaling upregulation does not lead to protrusion formation in these embryos (Figure S6G). Together with the chemokine analysis, these results suggest that it is not the ectopic expression of cxcl12a or ectopic Fgf signaling that induces filopodia formation, but the loss of Fgf signaling within the prim and/or associated loss of HSPGs within the prim or surrounding tissues.

Discussion

Collective cell migration is a fascinating and complex process that requires communication between cells, as well as interactions with the extracellular environment. We show that the migrating LL prim is an excellent model to study the integration of cell-autonomous and non-cell autonomous signaling to ensure coordinated migration of groups of cells. We have previously identified a feedback loop between the major signaling pathways involved in prim migration. This knowledge allows us to investigate the mechanisms that control and modulate these pathways in the extracellular space.

Elegant studies in mice demonstrated that HSPGs modulate FGF receptor function and local retention of FGF ligands during early embryogenesis (Matsuo and Kimura-Yoshida, 2013; Yayon et al., 1991). However, as mouse mutations in HSPG biosynthesis genes are embryonic lethal, the investigation of HSPG function was restricted to gastrulation stages. We show that HSPGs are also essential for Fgf signal transduction and restriction of ligand diffusion during vertebrate organ formation. Importantly, we determined functions of HSPGs during collective cell migration, an embryonic process that is difficult to study in mice.

HSPGs are induced by Wnt and Fgf signaling

We have discovered that HSPGs are crucial members of a tightly controlled feedback loop that orchestrates collective cell migration and morphogenesis. Our finding that HSPGs are targets of the pathways that they control has fundamental implications for the interpretation of ext mutant phenotypes. The phenotypes could be due to the lost ability of HSPGs to bind ligands, or the defects could be caused by loss of entire HSPG proteins such as gpc4, sdc3 and sdc4 after Fgf signaling inhibition (Figure 1N-1P). Similarly, gpc1b, a Wnt target expressed in only a few cells in the leading region of the prim shows drastic upregulation in extl3/ext2 mutants, secondary to the expansion of Wnt activation and Fgf inhibition. If HSPG core proteins possess HS-independent functions, the ectopic expression of gpc1b could contribute to the extl3/ext2 mutant phenotype. The feedback interactions between HSPGs and the pathways that they control make primordium-expressed HSPGs an accessible experimental paradigm to dissect how multiple signaling pathways are coordinated and modulated to produce complex cellular behaviors and functional tissues.

Mutations in ext genes affect Fgf signaling but not Wnt signal transduction in the primordium

HSPGs consist of HS chains covalently attached to a core protein (Bernfield et al., 1999). Mouse and zebrafish ext mutants lack adequate levels of HS and possess serious developmental defects as a result of failed activation of signaling pathways, like Wnt and Fgf (Fischer et al., 2011; Norton et al., 2005; Shimokawa et al., 2011). Our results support the requirement of ext genes in Fgf signaling, however some studies proposed that HSPGs also affect Wnt signaling directly (Dhoot et al., 2001). Our study shows that in the prim Wnt signaling is secondarily affected due to loss of the Fgf dependent Wnt inhibitor dkk1b. Results supporting this interpretation are: (a) When we activate Fgf signaling in NaClO3-treated embryos, Wnt signaling is again restricted to the leading region, demonstrating that HS are not required for Wnt restriction (Figure 4K-4L’). (b) When we downregulate Fgf signaling in 34 hpf extl3/ext2 mutants the expansion of lef1 and the onset of the phenotype is accelerated showing that loss of Fgf signaling is the primary cause of Wnt signaling expansion (Figure 3K-3L’).

Thus, our findings demonstrate that HS are not directly inhibiting Wnt signaling and they are not required to activate Wnt signaling during collective cell migration and prim development. In contrast, in Drosophila, HS enhance the interaction of the glypican Dally-like and the Wg ligand but the core protein by itself is also sufficient to interact with Wg (Yan et al., 2009). Such an interaction between Wnt ligands and HSPG core proteins cannot be ruled out in extl3/ext2 prim. Whether in extl3/ext2 mutants the naked core protein still interacts with Wnt ligands and is sufficient to induce Wnt signal transduction remains to be experimentally resolved.

HS limits Fgf ligand diffusion away from the prim

HSPGs have also been implicated in signaling molecule distribution and gradient formation (Yan and Lin, 2009). The tightly regulated feedback loop between the Wnt and Fgf signaling pathways in the prim represents a challenge when studying potential gradient formation as manipulating either pathway results in the disruption of the other, leading to complete loss or ubiquitous ligand expression. For example, mutations in both ext genes lead to the expansion of the Wnt domain causing the expression of Wnt and Fgf ligands along the entire length of the primordium, making it difficult to ascertain whether Wnt and Fgf ligands require HSPGs for diffusion. However, the formation of a halo of Fgf target expression in cells surrounding the HS-depleted prim provides a clue to whether ligand diffusion depends on HS.

A halo of Di-pERK is also observed around WT prim, however Fgf signaling is weaker than in cells surrounding mutant prim, as pea3 requires high levels of Fgf signaling and only forms a halo in the mutants. Two scenarios could explain the pea3 halo formation in mutant embryos. First, a pea3-positive halo could be the result of stalling of the prim that leads to increased diffusion of Fgf ligands into the surrounding tissue. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that stalled apcmcr prim that expresses fgf3 and fgf10 throughout the prim also form Fgf-dependent pea3-positive halos (Figure 1G-1H and Figure S5E-S5F). Second, HS in the prim or the surrounding tissues could act to restrict Fgf ligands to the primordium. The analyses of NaClO3-treated embryos, in which we rescued Fgf pathway activation in the leading region of the prim demonstrates that even in the presence of relatively low levels of Fgf ligands, ectopic Fgf target activation occurs robustly (Figure 4R’, 4T’ and Figure 7D). This finding suggests that ectopic activation of Fgf signaling surrounding the prim is caused by loss of HS and not the upregulation of Fgf ligands in the primordium. Halo formation in apcmcr prim can also be explained by the feedback between signaling pathways and HSPGs. Ectopic activation of Wnt signaling in apcmcr prim causes the loss of sdc4 and upregulation of gpc1b that likely affects Fgf ligand diffusion into the environment (Figure 1E and 1H). We conclude that HSPGs are not only required for Fgf signaling activation but also limit Fgf ligand diffusion and thereby play a critical role in spatially restricting Fgf signal activation.

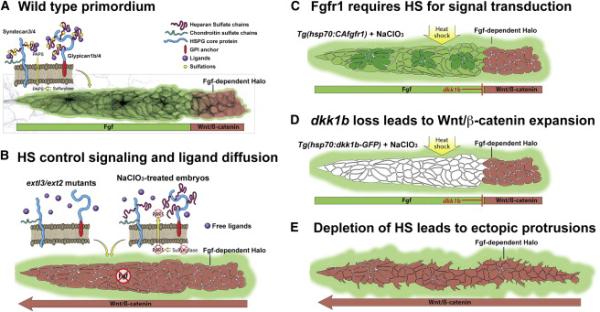

Figure 7. HSPGs control activation of Wnt and Fgf signaling, as well as cell polarity and ligand distribution during collective cell migration.

(A) HSPGs are expressed in discrete domains of the LL prim and their expression is dependent on Wnt or Fgf signaling making them part of a feedback loop. Fgf-dependent ERK signaling surrounds the border of the primordium. (B) Analysis of HS-depleted embryos (extl3/ext2 mutants or NaClO3-treated) revealed that HSPGs are important for localized Wnt and Fgf signaling activation, as well as to limit Fgf ligands diffusion away from the primordium. In the absence of HS, Fgf ligands activate Fgf signaling outside the primordium. (C) Constitutive activation of Fgfr1 rescues Fgf signaling in HS-depleted embryos, demonstrating that Fgf requires the presence of HS for Fgf signal transduction. (D) Induction of Dkk1b in HS-depleted embryos is sufficient to restrict Wnt back to the leading region, demonstrating that Wnt expands as a result of Fgf signaling loss. Dkk1b induction is not sufficient to rescue Fgf signaling, because HS are required for Fgf signal transduction in the primordium. Additionally, the Fgf-dependent pea3 halo is still present after CAfgfr1 and Dkk1b rescue experiments, as HS play an important role in limiting Fgf diffusion. (E) HS also control cell polarity of LL prim cells as HS-depleted embryos extend dynamic ectopic filopodia.

HS depletion induces the formation of highly dynamic filopodia in prim cells independently of ectopic cxcl12a or pea3 expression

extl3/ext2 prim develops highly dynamic ectopic protrusions once Wnt is maximally expanded and Fgf signaling is lost (Movie S4). The absence of HS in extl3/ext2 mutants leads to the formation of extra cxcl12a-expressing muscle cells that could affect cell polarity. Our results demonstrate that overexpression of cxcl12a is not sufficient to induce protrusions to a similar degree in WT embryos. Ectopic protrusions could also be caused by elevated levels of Fgf signaling in cells surrounding extl3/ext2 prim, as Fgfs attract LL cells (Dalle Nogare et al., 2014). However, global downregulation of Fgf signaling with SU542 in extl3/ext2 mutants does not abolish ectopic filopodia formation arguing that ectopic Fgf signaling is not attracting these filopodia (Movie S8).

As mutations in ext genes affect chain synthesis on all HSPGs, one or more of the HSPGs that are expressed in the prim or surrounding tissues could be responsible for maintaining prim cell polarity and inhibiting ectopic protrusions. sdc4 is an attractive candidate, as it is downregulated in extl3/ext2 mutants (data not shown). sdc4 is required in Xenopus and zebrafish neural crest cells where it regulates the induction of protrusions through Rho1/RacA signaling (Matthews et al., 2008). sdc4-depleted cells are motile but form protrusions in aberrant directions similarly to extl3/ext2 mutant LL cells. However, it remains to be tested whether sdc4 loss in extl3/ext2 mutants is sufficient to induce filopodia or whether other HSPGs are involved in regulating cell polarity. Nevertheless, our finding that HSPGs function in the establishment or maintenance of cell polarity during vertebrate collective cell migration may be relevant to many human diseases.

HSPG function in the migrating prim and implications for our understanding of human diseases

HSPGs regulate signaling pathways that control embryonic development and tissue homeostasis in adult animals. It is therefore not surprising that mutations in HSPGs and their modifying enzymes cause human disease. For example, proteoglycans influence the metastatic potential of cancer cells (Barash et al., 2010; Barbouri et al., 2014; Wade et al., 2013). Of particular interest with respect to our studies of HSPG function in cell migration is Kallmann syndrome, a condition characterized by hypogonadism and anosmia (Cadman et al., 2007; Di Schiavi and Andrenacci, 2013). Both phenotypes are caused by cell migration and axon pathfinding defects. The hormonal phenotype is caused by migration defects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons that are generated by the olfactory epithelium and populate the hypothalamus. Anosmia is caused by impaired projections of the olfactory sensory axons. Few genes have been associated with Kallmann syndrome, among them the extracellular glycoprotein Anosmin1 and Fgfr1 (Kim et al., 2008). Interestingly, the regulation of Fgf signaling by Anosmin1 is HSPG dependent. Anosmin1 interacts with Syndecans and Glypicans in C. elegans and it is essential for LL prim migration (Gonzalez-Martinez et al., 2004; Hudson et al., 2006; Yanicostas et al., 2008). Therefore, proteoglycans and their modifying enzymes are candidates for playing a causative role in causing Kallmann syndrome. Our result that certain HSPGs require Fgf signaling for their induction raises the interesting question whether Kallmann syndrome is only caused by a reduction of Fgf signaling or also by the resulting loss of HSPGs. To determine specific functions of HSPGs, future studies have to take the existence of feedback loops between HSPGs and the signaling pathways that they control, into account. Our discovery revealed a complexity that has not been previously appreciated and possibly led to the misinterpretation of Fgf signaling versus HSPG functions.

Our study has provided a detailed description and unique insight into the functions of HSPGs and their roles in regulating collective cell migration in a vertebrate. Collective cell migration in the prim is a highly dynamic process where cells constantly change position due to proliferation and deposition from the trailing portion of the prim. HSPGs control Fgf signaling and ligand diffusion across this field of highly dynamic cells and HSPGs are therefore integral parts of the self-organizing feedback loop that orchestrates cell migration, deposition and cell polarity of a collectively migrating group of cells (Figure 7A-7E). Our work of HSPG function does not only inform LL biology, but the comparison with other animal models also demonstrates that the knowledge gained is transferrable to different organs, morphogenesis and disease of other vertebrates.

Experimental Procedures

Fish strains

Please refer to Supplemental experimental procedures.

Genotyping

DNA was extracted in lysis buffer as described by ZIRC followed by PCR or High Resolution Melting Analysis (HRMA). Genotyping of extl3 and ext2 mutants was performed as described previously (Lee et al., 2004) or by HRMA using the MeltDoctor™ HRM master mix on an ABI7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system with primers: extl3-F(5’-AGCCATCCGAGACATGGTGGA-3’), extl3-R(5’-AGCCATCCGAGACATGGTGGA-3’), ext2-F(5’-GGGATGTTCCAGTTCTGGCCTCA-3’), ext2-R(5’-TGCGGCGGTCCAGACTCCAT-3’).

Drug treatments

Embryos were treated at 18 hpf with 200mM NaClO3 (Sigma-Aldrich, USA)for 24 hours at 28.5°C. Treated embryos were fixed in 4% PFA overnight at 4°C. HS inhibition was confirmed by 10E4 and 3G10 antibody staining (USBiological, USA) and pea3 and lef1 in situs. SU5402 (Tocris, USA) treatment: inhibition of pea3 halo and dp-ERK in ext mutants and NaClO3-treated embryos (25μM – 42-48 hpf); ectopic protrusions (12.5μM - 24 hours); extl3/ext2 protrusions (40μM from 58-68 hpf); Wnt induction in ext mutants (28-34 hpf – 20μM). To induce Wnt with 2μM BIO (Tocris, USA) embryos were treated from 24 – 48 hpf. Bmp was inhibited by immersion in 10 μM Dorsomorphin (Tocris, USA) from 12 - 48 hpf. All solutions and controls contained 1% DMSO in 0.5X E2 medium.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

The full open reading frame of gpc1b, gpc4, sdc3 and sdc4 was amplified and inserted into the pCS2+ vector using standard molecular cloning techniques. Probes used: lef1, pea3, sef, axin2, fgf3, fgf10, fgfr1, dkk1b, atoh1a, cxcr4b and cxcr7b (Aman and Piotrowski, 2008), wnt10a (Lush and Piotrowski, 2014) and cxcl12a (Li et al., 2004). Cloning of s100t was performed using Fw 5’-ACCAGCAGTCATCTCACCTC-3’ and Rv 5’-CACACATTCAACAAAGACCATCG-3’ primers. patched1 probe was generated from a full length clone. Whole mount immunostaining was performed according to standard protocols. Primary antibodies used: 4D9-mouse (Engrailed) 1:6 (Hybridoma), 10E4-mouse 1:200 (USBiological), ZO-1-mouse 1:200. For Di-pErk1/2-mouse 1:100 (Sigma-Aldrich), Glyofix was used as fixative at 4°C. For 3G10-mouse 1:200 (USBiological) samples were pretreated with Pro-K (1-4 min at RT) and digested for 2 hours with Hep-III (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C. DASPEI staining was performed as described (Lush and Piotrowski, 2014).

Heat shock treatments

Tg(hsp70:dkk1b-GFP) and Tg(hsp70:CAfgfr1) were treated with 1% DMSO or 200mM NaClO3 at 18 hpf for 20 hours, heat shocked at 39°C for 40 minutes and then recovered in DMSO or NaClO3 for 2 hours at 28.5°C. Embryos were sorted and fixed in 4% PFA O/N at 4°C. Tg(hsp70:sdf1a) were heat shocked at 28 hpf as described (Venkiteswaran et al., 2013).

Timelapse and imaging

Embryos were anesthetized with 4g/L MS-222 and mounted in 0.8% low melting point agarose in 0.5X E2 medium on a Mat-Tek imaging dish. Prim migration was followed between 36- 48 hpf by timelapse analysis using a 40X water objective on a Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope in a climate-controlled chamber. Recorded time lapses were max- projected and stitched in ZEN. In situ hybridization images were obtained on a Zeiss Axiocam compound scope using 10X and 40X-water objectives. Image processing was performed in Fiji.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. H. Knaut, F. Poulain and T. Ishitani for fish lines and A. Sánchez Alvarado, R. Krumlauf and A. Kozlovskaja-Gumbriene for valuable comments on the manuscript. We thank the U. of Utah CZAR and SIMR Aquatics Facility for excellent fish care. We are grateful to the SIMR Molecular Biology and Imaging Cores and M. Miller and J. Navajas Acedo for help with graphic design. We would also like to thank Drs. M. Vetter, D. Grunwald, C. Murthaugh, J. Yost, M. Lush, A. Aman and Piotrowski Lab members for valuable discussions. The disaccharide analysis was performed at the Complex Carbohydrate Research Center, supported in part by the NIH-funded Research Resource for Integrated Glycotechnology (5P41GM10339024) to P. Azadi. This work was funded by an American Cancer Research Scholar grant (RSG CCG 114528) to T.P. and institutional support from the Stowers Institute.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

M.V.G, acquisition of data and together with T.P. study conception and experimental design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising of the article. K.L.K., provided reagents and critical revision.

References

- Aman A, Nguyen M, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin dependent cell proliferation underlies segmented lateral line morphogenesis. Developmental biology. 2011;349:470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Wnt/beta-catenin and Fgf signaling control collective cell migration by restricting chemokine receptor expression. Developmental cell. 2008;15:749–761. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Multiple signaling interactions coordinate collective cell migration of the posterior lateral line primordium. Cell adhesion & migration. 2009;3:365–368. doi: 10.4161/cam.3.4.9548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman A, Piotrowski T. Cell-cell signaling interactions coordinate multiple cell behaviors that drive morphogenesis of the lateral line. Cell adhesion & migration. 2011;5:499–508. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.6.19113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barash U, Cohen-Kaplan V, Dowek I, Sanderson RD, Ilan N, Vlodavsky I. Proteoglycans in health and disease: new concepts for heparanase function in tumor progression and metastasis. The FEBS journal. 2010;277:3890–3903. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbouri D, Afratis N, Gialeli C, Vynios DH, Theocharis AD, Karamanos NK. Syndecans as Modulators and Potential Pharmacological Targets in Cancer Progression. Frontiers in oncology. 2014;4:4. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernfield M, Gotte M, Park PW, Reizes O, Fitzgerald ML, Lincecum J, Zako M. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annual review of biochemistry. 1999;68:729–777. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse M, Feta A, Presto J, Wilen M, Gronning M, Kjellen L, Kusche-Gullberg M. Contribution of EXT1, EXT2, and EXTL3 to heparan sulfate chain elongation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:32802–32810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703560200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse-Wicher M, Wicher KB, Kusche-Gullberg M. The extostosin family: Proteins with many functions. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadman SM, Kim SH, Hu Y, Gonzalez-Martinez D, Bouloux PM. Molecular pathogenesis of Kallmann's syndrome. Hormone research. 2007;67:231–242. doi: 10.1159/000098156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitnis AB, Nogare DD, Matsuda M. Building the posterior lateral line system in zebrafish. Developmental neurobiology. 2012;72:234–255. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement A, Wiweger M, von der Hardt S, Rusch MA, Selleck SB, Chien CB, Roehl HH. Regulation of zebrafish skeletogenesis by ext2/dackel and papst1/pinscher. PLoS genetics. 2008;4:e1000136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Nogare D, Somers K, Rao S, Matsuda M, Reichman-Fried M, Raz E, Chitnis AB. Leading and trailing cells cooperate in collective migration of the zebrafish posterior lateral line primordium. Development. 2014;141:3188–3196. doi: 10.1242/dev.106690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambly-Chaudiere C, Cubedo N, Ghysen A. Control of cell migration in the development of the posterior lateral line: antagonistic interactions between the chemokine receptors CXCR4 and CXCR7/RDC1. BMC developmental biology. 2007;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David NB, Sapede D, Saint-Etienne L, Thisse C, Thisse B, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Rosa FM, Ghysen A. Molecular basis of cell migration in the fish lateral line: role of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and of its ligand, SDF1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:16297–16302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252339399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhoot GK, Gustafsson MK, Ai X, Sun W, Standiford DM, Emerson CP., Jr. Regulation of Wnt signaling and embryo patterning by an extracellular sulfatase. Science. 2001;293:1663–1666. doi: 10.1126/science.293.5535.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Schiavi E, Andrenacci D. Invertebrate models of kallmann syndrome: molecular pathogenesis and new disease genes. Current genomics. 2013;14:2–10. doi: 10.2174/138920213804999174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dona E, Barry JD, Valentin G, Quirin C, Khmelinskii A, Kunze A, Durdu S, Newton LR, Fernandez-Minan A, Huber W, et al. Directional tissue migration through a self-generated chemokine gradient. Nature. 2013;503:285–289. doi: 10.1038/nature12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S, Filipek-Gorniok B, Ledin J. Zebrafish Ext2 is necessary for Fgf and Wnt signaling, but not for Hh signaling. BMC developmental biology. 2011;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldez AJ, Copley RR, Cohen SM. HSPG modification by the secreted enzyme Notum shapes the Wingless morphogen gradient. Developmental cell. 2002;2:667–676. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Martinez D, Kim SH, Hu Y, Guimond S, Schofield J, Winyard P, Vannelli GB, Turnbull J, Bouloux PM. Anosmin-1 modulates fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 signaling in human gonadotropin-releasing hormone olfactory neuroblasts through a heparan sulfate-dependent mechanism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:10384–10392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3400-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Brand M. Identification and expression analysis of zebrafish glypicans during embryonic development. PloS one. 2013;8:e80824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding MJ, Nechiporuk AV. Fgfr-Ras-MAPK signaling is required for apical constriction via apical positioning of Rho-associated kinase during mechanosensory organ formation. Development. 2012;139:3130–3135. doi: 10.1242/dev.082271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson ML, Kinnunen T, Cinar HN, Chisholm AD. C. elegans Kallmann syndrome protein KAL-1 interacts with syndecan and glypican to regulate neuronal cell migrations. Developmental biology. 2006;294:352–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilina O, Friedl P. Mechanisms of collective cell migration at a glance. Journal of cell science. 2009;122:3203–3208. doi: 10.1242/jcs.036525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Hu Y, Cadman S, Bouloux P. Diversity in fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 regulation: learning from the investigation of Kallmann syndrome. Journal of neuroendocrinology. 2008;20:141–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2007.01627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuger J, Perez L, Giraldez AJ, Cohen SM. Opposing activities of Dally-like glypican at high and low levels of Wingless morphogen activity. Developmental cell. 2004;7:503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecaudey V, Cakan-Akdogan G, Norton WH, Gilmour D. Dynamic Fgf signaling couples morphogenesis and migration in the zebrafish lateral line primordium. Development. 2008;135:2695–2705. doi: 10.1242/dev.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, von der Hardt S, Rusch MA, Stringer SE, Stickney HL, Talbot WS, Geisler R, Nusslein-Volhard C, Selleck SB, Chien CB, et al. Axon sorting in the optic tract requires HSPG synthesis by ext2 (dackel) and extl3 (boxer). Neuron. 2004;44:947–960. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Shirabe K, Kuwada JY. Chemokine signaling regulates sensory cell migration in zebrafish. Developmental biology. 2004;269:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Perrimon N. Role of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell-cell signaling in Drosophila. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology. 2000;19:303–307. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lush ME, Piotrowski T. ErbB expressing Schwann cells control lateral line progenitor cells via non-cell-autonomous regulation of Wnt/beta-catenin. eLife. 2014;3:e01832. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. The FEBS journal. 2010;277:3876–3889. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda M, Nogare DD, Somers K, Martin K, Wang C, Chitnis AB. Lef1 regulates Dusp6 to influence neuromast formation and spacing in the zebrafish posterior lateral line primordium. Development. 2013;140:2387–2397. doi: 10.1242/dev.091348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo I, Kimura-Yoshida C. Extracellular modulation of Fibroblast Growth Factor signaling through heparan sulfate proteoglycans in mammalian development. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2013;23:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews HK, Marchant L, Carmona-Fontaine C, Kuriyama S, Larrain J, Holt MR, Parsons M, Mayor R. Directional migration of neural crest cells in vivo is regulated by Syndecan-4/Rac1 and non-canonical Wnt signaling/RhoA. Development. 2008;135:1771–1780. doi: 10.1242/dev.017350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya AK, Tan H, Souren M, Wang X, Wittbrodt J, Ingham PW. Integration of Hedgehog and BMP signalling by the engrailed2a gene in the zebrafish myotome. Development. 2011;138:755–765. doi: 10.1242/dev.062521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogdans J, Bleckmann H. Coping with flow: behavior, neurophysiology and modeling of the fish lateral line system. Biological cybernetics. 2012;106:627–642. doi: 10.1007/s00422-012-0525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell DJ, Yoon WH, Starz-Gaiano M. Group choreography: mechanisms orchestrating the collective movement of border cells. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:631–645. doi: 10.1038/nrm3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechiporuk A, Raible DW. FGF-dependent mechanosensory organ patterning in zebrafish. Science. 2008;320:1774–1777. doi: 10.1126/science.1156547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton WH, Ledin J, Grandel H, Neumann CJ. HSPG synthesis by zebrafish Ext2 and Extl3 is required for Fgf10 signalling during limb development. Development. 2005;132:4963–4973. doi: 10.1242/dev.02084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulain FE, Chien CB. Proteoglycan-mediated axon degeneration corrects pretarget topographic sorting errors. Neuron. 2013;78:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P. Fellow travellers: emergent properties of collective cell migration. EMBO reports. 2012;13:984–991. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaiyan F, Kolset SO, Prydz K, Gottfridsson E, Lindahl U, Salmivirta M. Selective effects of sodium chlorate treatment on the sulfation of heparan sulfate. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:36267–36273. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin AF, Nunez VA, Sapede D, Tassin V, Dambly-Chaudiere C, Ghysen A. Origin and early development of the posterior lateral line system of zebrafish. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:8234–8244. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5137-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3. 2011 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiau CE, Hu N, Bronner-Fraser M. Altering Glypican-1 levels modulates canonical Wnt signaling during trigeminal placode development. Developmental biology. 2010;348:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu N, Kawakami K, Ishitani T. Visualization and exploration of Tcf/Lef function using a highly responsive Wnt/beta-catenin signaling-reporter transgenic zebrafish. Developmental biology. 2012;370:71–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimokawa K, Kimura-Yoshida C, Nagai N, Mukai K, Matsubara K, Watanabe H, Matsuda Y, Mochida K, Matsuo I. Cell surface heparan sulfate chains regulate local reception of FGF signaling in the mouse embryo. Developmental cell. 2011;21:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Ozawa Y, Sato M, Watanabe A, Tabata T. Three Drosophila EXT genes shape morphogen gradients through synthesis of heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Development. 2004;131:73–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.00913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topczewski J, Sepich DS, Myers DC, Walker C, Amores A, Lele Z, Hammerschmidt M, Postlethwait J, Solnica-Krezel L. The zebrafish glypican knypek controls cell polarity during gastrulation movements of convergent extension. Developmental cell. 2001;1:251–264. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentin G, Haas P, Gilmour D. The chemokine SDF1a coordinates tissue migration through the spatially restricted activation of Cxcr7 and Cxcr4b. Current biology : CB. 2007;17:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkiteswaran G, Lewellis SW, Wang J, Reynolds E, Nicholson C, Knaut H. Generation and dynamics of an endogenous, self-generated signaling gradient across a migrating tissue. Cell. 2013;155:674–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade A, Robinson AE, Engler JR, Petritsch C, James CD, Phillips JJ. Proteoglycans and their roles in brain cancer. The FEBS journal. 2013;280:2399–2417. doi: 10.1111/febs.12109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Lin X. Drosophila glypican Dally-like acts in FGF-receiving cells to modulate FGF signaling during tracheal morphogenesis. Developmental biology. 2007;312:203–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Lin X. Shaping morphogen gradients by proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology. 2009;1:a002493. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Wu Y, Feng Y, Lin SC, Lin X. The core protein of glypican Dally-like determines its biphasic activity in wingless morphogen signaling. Developmental cell. 2009;17:470–481. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanicostas C, Ernest S, Dayraud C, Petit C, Soussi-Yanicostas N. Essential requirement for zebrafish anosmin-1a in the migration of the posterior lateral line primordium. Developmental biology. 2008;320:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayon A, Klagsbrun M, Esko JD, Leder P, Ornitz DM. Cell surface, heparin-like molecules are required for binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its high affinity receptor. Cell. 1991;64:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90512-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SR, Burkhardt M, Nowak M, Ries J, Petrasek Z, Scholpp S, Schwille P, Brand M. Fgf8 morphogen gradient forms by a source-sink mechanism with freely diffusing molecules. Nature. 2009;461:533–536. doi: 10.1038/nature08391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.