Abstract

Background

Increasing access to essential respiratory medicines and influenza vaccination has been a priority for over three decades. Their use remains low in low and middle income countries (LMICs) where little is known about factors influencing use, or about the use of influenza vaccination for preventing respiratory exacerbations.

Methods

We estimated rates of regular use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccine, and predictors for use among 19,000 adults from 23 high (HIC) and LMIC sites.

Findings

Bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccine were used significantly more in HIC than in LMICs after adjusting for similar clinical needs. Although used more commonly by people with symptomatic or severe respiratory disease, the gap between HIC and LMICs is not explained by prevalence of COPD or doctor-diagnosed asthma. Site-specific factors are likely to influence use differently. The gross national income per capita for the country is a strong predictor for use of these treatments, suggesting that economics influence under-treatment.

Conclusion

A better understanding of determinants for low use of essential respiratory medicines and influenza vaccine in low income settings remains important. Identifying and addressing these more systematically could improve access and use of effective treatments.

Keywords: essential respiratory medications, prevention of exacerbations, determinants for use, COPD and asthma treatments

Background

Universal access to essential respiratory medicines and to influenza vaccine has been on the World Health Organisation public health agenda for over three decades. Salbutamol, beclomethasone, ipratropium bromide, theophylline, budesonide and influenza vaccine were first included on the List of Essential Medicines in the 1970s1 to increase accessibility for people with chronic respiratory conditions.2 The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) recommends the prescription of inhaled bronchodilators as regular treatment for symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and additional prescription of inhaled corticosteroids for the treatment of frequent exacerbations of COPD.3 Recommendations are also made by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) for the use of these medications in the treatment of asthma.4 Initiatives such as the Global Alliance Against Chronic Respiratory Disease and the Asthma Drug Facility were set-up to support the management of asthma and COPD and increase access to essential respiratory medicines, but studies have persistently shown poor access to selected essential respiratory medications in low and middle income countries.5-7 This has been attributed to poor availability of generic drugs in the public sector, the high price of brand drugs in private pharmacies and low affordability compared with local wages.6-8 One study has shown that the cost of a standard treatment for asthma is higher in less affluent places, indicating some level of market failure.5 The use of influenza vaccine as a preventive measure for exacerbations in people with COPD has been shown to be beneficial9 although its benefit for asthmatic patients remains controversial.10 A few studies have investigated the uptake of influenza vaccine among patients with COPD11 and health care workers12 but they are relatively limited in scope.

To our knowledge, no studies have yet described the use of respiratory medications or uptake of influenza vaccine according to need and individual determinants for use. In this paper we describe differences in rate of use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccination and predictors for use at 23 sites in 20 countries participating in the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease (BOLD) study.

Methods

BOLD is a cross-sectional survey assessing prevalence and burden of COPD. At each site, representative simple or cluster random samples of non-institutionalised adults aged 40 years and over, living in well-defined administrative areas (table1) answered detailed questionnaires and performed spirometry after the safety criteria check was satisfied.13

Table1. Weighted rates of use of respiratory medications and influenza vaccine among BOLD sites.

| Any Bronchodilators or any Inhaled Corticosteroids | Influenza vaccine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOLD sites | Population weighted rate1 (%, SE) | Standardised rate for clinical need2 (%, N3) | Population weighted rate1 (%, SE) | Standardised rate for clinical need2 (%, N3) |

| High Income Countries | ||||

| Bergen, Norway | 8.9 (1.1) | 32.2 (4) | 21.7 (1.5) | 38.8 (7) |

| Hannover, Germany | 8.4 (1.1) | 52.9 (9) | 37.9 (2.0) | 42.2 (4) |

| Krakow, Poland | 7.7 (1.1) | 37.6 (8) | 7.2 (1.0) | 12.4 (1) |

| Lexington, USA | 22.9 (1.9) | 56.9 (25) | 38.5 (2.2) | 39.8 (20) |

| Lisbon, Portugal | 9.3 (0.9) | 32.4 (8) | 25.8 (2.2) | 27.3 (7) |

| London, England | 18.2 (2.2) | 58.1 (19) | 40.2 (2.5) | 60.9 (23) |

| Maastricht, Netherlands | 13.1 (1.6) | 45.5 (15) | 41.4 (2.2) | 50.4 (16) |

| Reykjavik, Iceland | 15.6 (1.3) | 51.1 (9) | 32.9 (1.7) | 35.2 (7) |

| Salzburg, Austria | 5.5 (0.7) | 36.4 (14) | 18.9 (1.2) | 24.4 (4) |

| Sydney, Australia | 17.4 (1.6) | 52.9 (10) | 33.4 (2.0) | 40.1 (6) |

| Tartu, Estonia | 4.3 (0.8) | 30.7 (2) | 6.2 (1.0) | 6.2 (0) |

| Uppsala, Sweden | 15.2 (1.5) | 47.5 (5) | 21.0 (1.8) | 15.3 (2) |

| Vancouver, Canada | 16.8 (1.3) | 50.2 (13) | 45.9 (1.7) | 52.5 (13) |

| Low and Middle Income Countries | ||||

| Adana, Turkey | 4.9 (0.7) | 16.0 (8) | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.5 (1) |

| Cape Town, South Africa | 7.8 (0.9) | 26.7 (18) | 4.8 (0.8) | 2.5 (2) |

| Ile-Ife, Nigeria | 0.6 (0.3) | 25.6 (1) | 0.6 (0.3) | 0.2 (0) |

| Guangzhou, China | 1.1 (0.4) | 27.2 (2) | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.5 (0) |

| Manila, Philippines | 3.7 (0.7) | 37.0 (7) | 0.8 (0.4) | 1.0 (0) |

| Mumbai, India | 3.9 (1.5) | 35.7 (3) | 0.4 (0.3) | 4.9 (1) |

| Nampicuan&Talugtug, Philippines | 3.6 (0.8) | 11.3 (6) | 0.3 (0.2) | 2.7 (1) |

| Pune, India | 1.2 (0.3) | 20.4 (3) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Sousse, Tunisia | 3.5 (0.8) | 30.6 (5) | 56.6 (3.2) | 69.7 (9) |

| Srinagar, India | 2.4 (0.6) | 41.9 (4) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.0 (0) |

Population estimated rate of use, weighted for survey design at each site (US, Canada and Iceland had simple random samples, China, Austria, Germany, Poland, Norway, Australia, England, Sweden, The Netherlands, Estonia, and Pune had stratified random samples, S.Africa had a cluster random sample, Turkey, Philippines, Mumbai, Portugal, Tunisia, Srinagar and Nigeria had stratified cluster samples)

Directly standardised rate of use among standard studied groups of adults aged 50-69 years, with spirometrically confirmed COPD stage 2+ with wheeze or with dyspnoea stage 2+., weighted for survey design at each site.

N refers to the number of individuals in the sample who fall under the standard definition, based on whom the weighted results reported were made.

Regular use of respiratory medicines and uptake of influenza vaccine in the last 12 months were reported by study participants through face-to-face interviews conducted in the subject’s native language by trained, certified staff. The specific brand or generic drug name and formulation reported were further classified under standard classes of respiratory medication according to the British National Formulary.

Chronic Airways Obstruction (CAO) was defined as a post-bronchodilator (post-BD) ratio of the one second forced expiratory volume (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) below the lower limit of normal (LLN) for age and sex, based on reference equations for Caucasians derived from the third US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.14 The severity of COPD was further defined using the cut-offs of >80, <80 and <50 of post-BD FEV1 % predicted for stage 1, 2 and 3 respectively.15 Standardised, quality-controlled spirometry was performed by certified technicians according to the American Thoracic Society criteria, using the ndd Easy One™ spirometer.16

Doctor-diagnosed asthma was self-reported. A positive response to salbutamol (indicating asthma) in those without CAO was defined as a difference between post and pre-BD FEV1≥200 ml and ≥12%.17 Respiratory symptoms (Medical Research Council dyspnoea, wheeze, cough or phlegm) and comorbidities (doctor-diagnosed heart disease, hypertension, stroke, lung cancer, diabetes, tuberculosis) were self-reported. Reported diagnosed asthma or COPD stage 2+ with dyspnoea or wheeze are generically referred to as chronic respiratory disease.

The central co-ordination of the study was approved by the UK National Research Ethics Service. Each participating site obtained local ethical approvals for conducting the survey. Participants gave written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

We report:

-

1)

the use of bronchodilators, corticosteroids, anticholinergics, β-agonists, theophylline and combinations and uptake of influenza vaccine relative to those on any respiratory medication by chronic respiratory disease and by country income (e.g. (Total number of participants on bronchodilators in HIC / Total number of participants on any respiratory medication in HIC)*100);

-

2)the use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccine as:

-

a)Estimated rates of use among those with and without spirometrically confirmed COPD stage 2+, adjusted for survey design at each site;

-

b)directly standardised rates of use for clinical need, estimated assuming a standard group (those aged 50-69 years) with a similar clinical need (spirometrically confirmed COPD stage 2+ and with wheeze or with dyspnoea stage 2+) adjusted for survey design at each site.

-

a)

Predictors for use of any bronchodilator, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccine were examined by multiple logistic regressions and meta-analyses. Identical models were fitted separately at each BOLD site with adjustment for sex, age, education level (none/primary, secondary, tertiary), employment status (‘employed’/worked for an income, ‘breathing related work disability’/unable to work for an income due to breathing problems, ‘homemaker’/full-time homemaker or caregiver not working for an income and ‘unemployed or retired’ in the last 12 months), smoking history, respiratory symptoms, severity of COPD, positive response to salbutamol (suggestive of asthma), comorbidities and body mass index (BMI) (<20, 20-25, >25) (for medicines only). At each site, the effects of all these predictors were mutually adjusted and estimated taking into account the sampling design. Subsequently, the results for each predictor were pooled across all sites using meta-analysis.18 The between-site variation in the effect size of each predictor in relation to use of treatments was assessed by the I2 statistic for heterogeneity. 19

In addition, we used generalised estimating equations to assess the association of the Gross National Income Per Capita of the country (GNIPC)20 with use of selected treatments at each site (independent of the individual predictors above). The GNIPC was grouped as low income (<5,000 US$), middle income (5,000 to 9,999 US$), low high income (10,000 to 29,999 US$) and high income (≥30,000 US$). Analyses were done using Stata 12. Significance refers to p<0.05.

Results

Over 19,220 subjects answered questionnaires on use of respiratory medications, influenza vaccine and doctor-diagnosed respiratory disease. Over 15,590 individuals also performed acceptable spirometry and had complete information on all variables of interest.

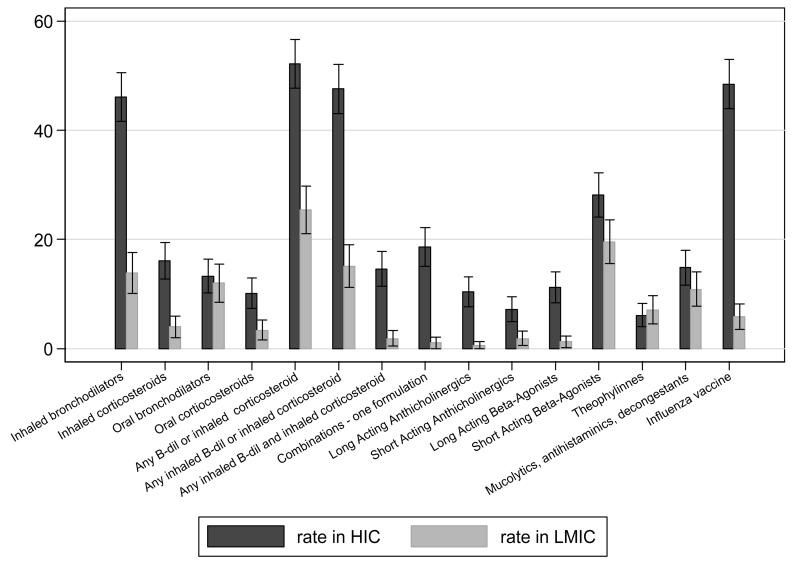

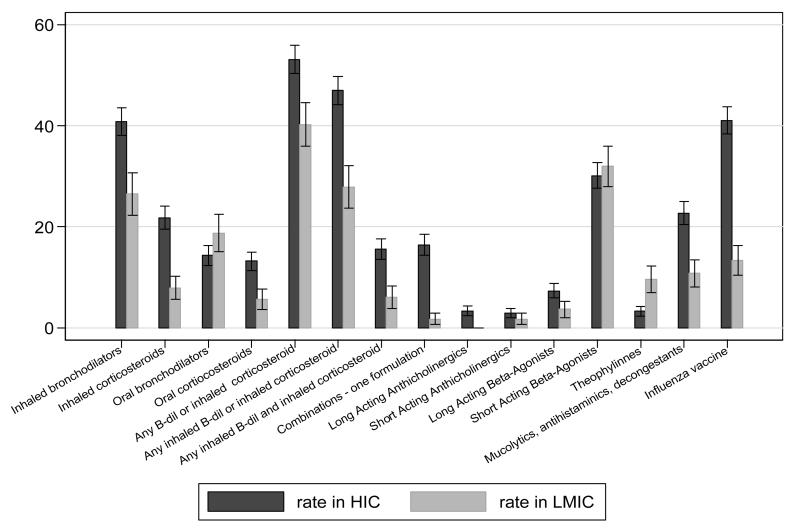

Rates of use of bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids range from <1% of the general population over the age of 40 years in Ile-Ife (Nigeria) to 23% in Lexington (USA) (Table 1). The probability of being treated for a standard group of 50-69 year olds with Stage2 COPD and either dyspnoea or wheeze ranged from 11% in Nampicuan and Talugtug (Philippines) to 58% in London (UK), with rural populations appearing to be under-treated when compared to urban populations with a similar need in the same country (11% vs 37% in Philippines; 20% vs 36% in India). Rates of influenza vaccine uptake ranged from 0% in Pune and Srinagar (India) to 57% in Sousse (Tunisia), while the probability of being vaccinated ranged from 0% in India to 70% in Sousse (Tunisia) among the same standard group. The use of any class of respiratory medicines and influenza vaccines was more common in HIC than in LMICs for those with symptomatic Stage2 COPD (Fig 1A) or doctor-diagnosed asthma (Fig 1B). Theophylline, oral bronchodilators and short-acting beta-agonists were marginally more likely to be used by those with symptomatic COPD or by asthmatic patients in LMICs compared with HICs (RR>1).

Figure 1. The relative rate of use (sample unweighted) of classes of respiratory medicines and flu vaccine, by chronic respiratory conditions and by country income.

A in Subjects with COPD GOLD stage 2+ with dyspnea or wheeze

Rate for each class of medicines calculated as (Total number of subjects with symptomatic COPD stage 2 on a particular class of medicines in HIC / Total number of subjects with symptomatic COPD stage 2 on any respiratory medicines in HIC )*100

Figure 1. The relative rate of use (sample unweighted) of classes of respiratory medicines and flu vaccine, by chronic respiratory conditions and by country income.

B in Subjects with reported doctor-diagnosed asthma

Rate for each class of medicines calculated as (Total number of subjects with symptomatic COPD stage 2 on a particular class of medicines in HIC / Total number of subjects with symptomatic COPD stage 2 on any respiratory medicines in HIC )*100

The distribution of the baseline characteristics among users of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids or influenza vaccine were similar among high and low income countries. Users were more likely to be women, aged 60 years or more, unemployed or retired, obese, heavy smokers, unable to work due to breathing problems, complaining of respiratory symptoms, with severe COPD, doctor-diagnosed asthma or comorbidities (results not shown). In these unadjusted figures, influenza vaccine had significantly lower uptake among those with higher levels of education in LMICs (RR=0.6) and significantly higher uptake in those with breathing related work disability (RR=2.9) and those with severe COPD (RR=2.1) in HICs.

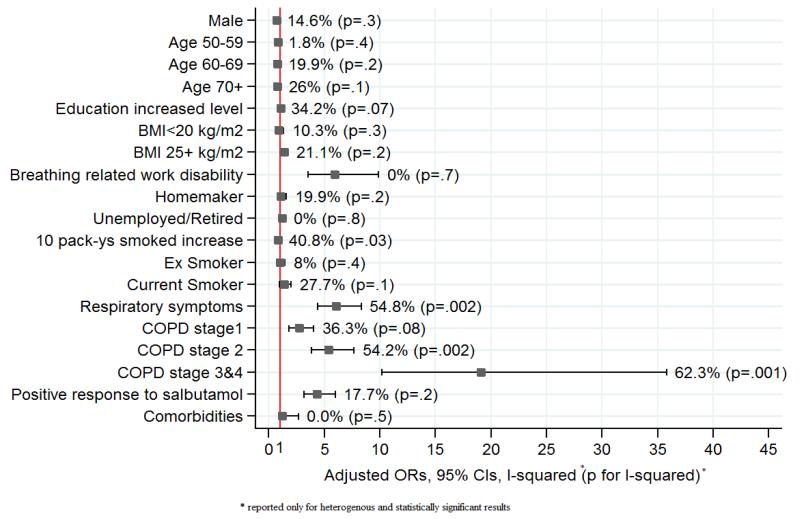

After mutual adjustment for all other potential predictors for use, men were less likely to report using bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids (OR=0.73, 95%CI 0.61-0.87) and these medications were increasingly likely with increasing severity of COPD (OR=19.1, 95%CI 10.2-35.8 for stages 3&4), respiratory symptoms (OR=6.0, 95%CI 4.4-8.3) and breathing related loss of work (OR=5.9, 95%CI 3.5-9.9) (Fig 2). Those who were overweight were also more likely to be using treatment (OR=1.4, 95%CI 1.1-1.7), as were those with a positive response to salbutamol (OR=4.4, 95%CI 3.2-6.0). Age, smoking and comorbidities were not significantly associated with using treatments. Similar trends were seen in HICs and in LMICs (results not shown). The effect of having COPD stage 2+ or respiratory symptoms on increasing use of medicines, was greater in HICs compared to LMICs (OR=5.7 vs 4.7 and 6.5 vs 4.9 (p<0.05) respectively), while work disability related to breathing problems and a positive response to salbutamol (suggestive of asthma) appear to have a stronger effect on use in LMICs (OR=6.8 vs 5.2 and 7.1 vs 3.4, (p<0.05). Similar results were seen when analyses were confined to subjects with spirometrically confirmed CAO (results not shown). There was significant variation in the influence of COPD stage 2+ (I2=54.2%, p=0.002) and respiratory symptoms (I2=54.8%, p=0.002) across sites, in relation to use of bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids (Fig 2). The association between symptoms and medication use was more variable among HICs (I2=65.9%, p<0.0001) than LMICs (I2=0%, p=0.5).

Fig 2.

Predictors for use of Bronchodilators of inahied corticosteroids (Overall results from meta-analysis)

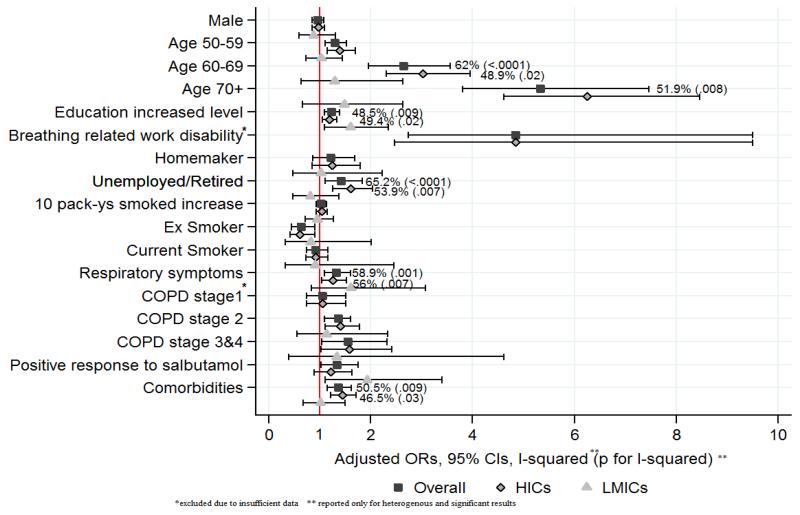

Influenza vaccination was more common in older participants (OR=5.3, 95%CI 3.8-7.5), the unemployed or retired (OR=1.4, 95%CI 1.1-1.8) and in those with higher education (OR=1.2, 95%CI 1.1-1.4) (Fig 3). It was more common in those with respiratory symptoms (OR=1.3, 95%CI 1.1-1.6), more severe COPD (OR=1.5, 95%CI 1.0-2.3), comorbidities (OR=1.4, 95%CI 1.1-1.6) and in those who had a positive response to salbutamol (OR=1.3, 95%CI 1.0-1.7). These associations varied between sites. Age (I2=62%, p<0.0001), level of education (I2=49.8%, p=0.009), respiratory symptoms (I2=58.9%, p=0.001) and comorbidities (I2=50.5%, p=0.009) had different effects across different sites. The associations with age, unemployment or retirement and comorbidities were more heterogeneous in HICs.

Fig 3.

Predictors for influenza vaccine uptake (results from meta-analysis)

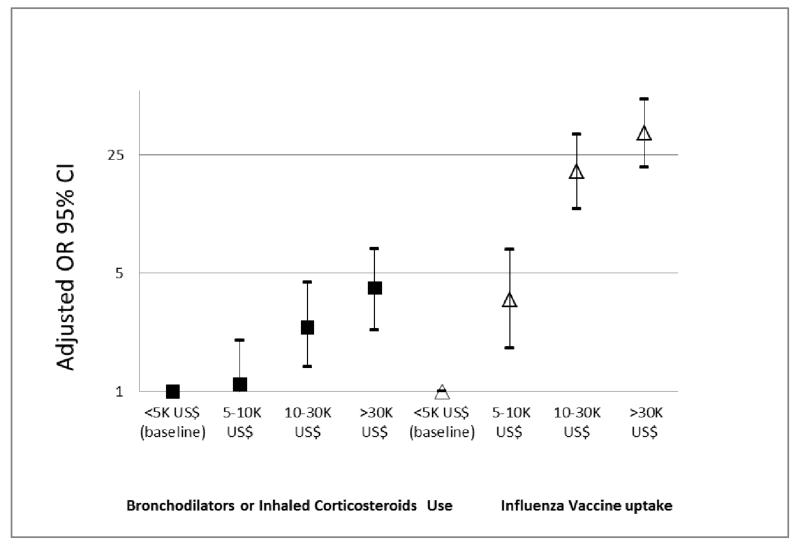

Increased GNIPC for the country was independently associated with increased use of bronchodilators, inhaled steroids and vaccination against influenza after adjusting for all other covariates (Fig 4). Compared to low income sites, the reported use of medication was 10% higher in middle-income sites, 140% higher in low-high-income sites and 310% higher in high-income sites. The uptake of influenza vaccination increased exponentially with increase in the country income per capita.

Figure 4. Association of the GNIPC with use of selected medications and influenza vaccination.

Adjusted for all predictors in figures 2 and 3.

GNIPC <5K US$ (Low Income- baseline): India, Philippines, China, Tunisia, Nigeria

GNIPC 5-10K US$ (Middle Income): S Africa, Turkey

GNIPC 10-30K US$ (Low- High Income): Poland, Estonia, Portugal

GNIPC 30k+ US$ (High Income): Iceland, UK, Canada, Germany, Australia, USA, Austria, Netherlands, Sweden, Norway

Discussion

In this large, highly standardised, multi-centre study, the regular use of respiratory medications in general and the use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids or influenza vaccine in particular, were significantly higher in HICs than in LMICs. Although the use of these medicines and vaccine were significantly more common in people with symptomatic chronic respiratory disease, there are important variations even among HIC and LMIC populations with a similar clinical need. The gap in use of these treatments between HIC and LMIC sites cannot be explained by differences in the prevalence of COPD or doctor-diagnosed asthma alone. The GNIPC correlates strongly with the uptake of medicines and influenza vaccine. Although not a direct measure of treatment affordability and providing little information on determinants at an individual level, this finding suggests that economic factors are likely to influence access to treatment.

We have opted for an ‘inclusive’ approach, looking at determinants for use of treatments in those with or without confirmed airflow obstruction (rather than stratifying by a specific chronic respiratory disease), to given an overall view of prescribing practice in the population, to allow for the effects of different pathologies and different levels of disease. We have also provided an analysis for a particular group of participants with a clearly defined need for medication.

The increased use of bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids with chronic respiratory disease and related work disabilities it is not surprising, suggesting that prescriptions are largely related to symptoms reported by the patient, as recommended by GOLD and GINA. Exacerbations were too rare to assess associations with treatments. However, the increasing use of these medicines with increase in severity of disease suggests that treatment is probably more likely in those with exacerbations. What is more important is the variation in rate of use among those with a similar clinical need for bronchodilators or inhaled steroids, even within high and within low income populations.

Low uptake of salbutamol and beclomethasone inhalers in less affluent countries has been attributed to the high costs of drugs, out-of-pocket purchasing, unsubsidised treatments, poor access to health insurance, local price regulation and lack of efficient markets.5-8,21 The strong association between use of medications and GNIPC, even after accounting for differences in the prevalence of symptoms, suggests that economic factors, possibly related to income, affordability and availability, might explain the lower rate of use at the BOLD sites in LMICs. The markets for these treatments are complex. Cost and availability may vary separately and influence use through different mechanisms. In a study of the public and private sectors in Africa, for instance, Cameron et al showed that an inhaler is cheaper (equivalent of 1.6 days wages for a month’s supply) but less available in the public sector (in only 14% outlets) compared with the private sector where the drug is more expensive (equivalent to 2.5 days wages per month) but more available (in 47% outlets). 7 Mendis et al showed that the cost of a standard course of treatment with salbutamol and beclometasone inhalers for asthma was both cheaper (equivalent to 1.3 days wages per month) and more available in Bangladesh (in 5.5% of outlets), compared with Malawi where the same treatments are not only more expensive (the equivalent of 9.2 days wages per month) but also less available (in only 0.4% outlets).6

Babar et al show that local policies and local markets can influence differences in use among sites.8 Regrettably, we do not have further information to explain variations between sites at a similar economic level in the BOLD study. Ecological studies might not always reflect determinants for use of respiratory treatment at an individual level. According to the Global Asthma Report 2011, the cost for one salbutamol inhaler is the equivalent of 0.5 days wages in China and 3.3 days wages in Nigeria.22 BOLD estimates for use of bronchodilators or inhaled corticosteroids by those with similarly low lung function and respiratory symptoms were 27% in China and 26% in Nigeria. Although these observations come from different studies with different designs, they suggest that the use of these medicines is probably less elastic where there is clear evidence of disease, and that uptake is less variable among those with clearer indications of more severe disease.

Our estimated rates of selected medicines according to need correlate with the country income in most, but not in all cases. The standardised estimates, although lower in LMICs compared to HICs, do vary across HICs (i.e. 36% in Austria, 53% in Germany) as well as across LMICs (i.e. 16% in Turkey, 27% in S. Africa). Bergen (Norway), the richest of the HIC sites, had the lowest estimate of use of selected medicines among HICs, while in Srinagar and Mumbai (India) and in Manila (Philippines), the rates are comparable to estimates in some HICs. Local guidelines for, and knowledge of clinicians about management of chronic respiratory diseases could explain some of these variations. In Norway where treatments are both available and affordable and clinicians are well trained and knowledgeable about chronic respiratory diseases, prescribing inhaled corticosteroids or combination therapy was not standard care for COPD at the time of the study. Currently, the benefit of these medicines is considered marginal unless patients have more severe COPD or experience frequent exacerbations.23 This may explain why Norway had lower treatment rates (32%) than Iceland (51%), despite the lower costs of medications.24 Changes in policy may explain the low rates of treatments in places like Tartu (Estonia) which experienced a major transition from ‘universal health care’ to a market economy and increase in out-of-pocket payments during recent decades.25 In India, Tunisia and urban Philippines, where availability or affordability might otherwise have been thought to be an issue, the high prescription rates could be explained by ‘better treatment,’ ‘inappropriate prescribing’, or differences in the access to and use of private versus public health care. However, differences in estimated rates of being treated for similar clinical needs between urban and rural sites in Philippines and in India suggest that rural populations are relatively undertreated. Whether this is due to the high cost of drugs, lack of services, expertise of local staff or other factors, remains unexplored. Local beliefs may be additional considerations in places where availability of treatments is not a major issue. In rural India, the use of inhalers has been associated with terminal illness, resulting in social stigma and discouraging use.26 In other places, Ayurverdic or other alternative therapies are preferred to conventional medical treatments. 27

In HICs the higher uptake of influenza vaccine with ageing, symptomatic and more severe COPD and comorbidities suggests that guidelines for vaccination among groups at risk are influencing practice. These associations were not seen in LMICs, probably due to very low rates of vaccination when compared to HICs (1.4% vs 28.4%, p<0.0001). These unusually low rates in LMICs, even in those with a clinical need, are perhaps because childhood vaccination is a public health priority, while adult vaccinations are provided mostly in private clinics. The association of higher education with increased rate of vaccination suggests that awareness and possibly the type of health service accessed are important, since those who are better educated tend to be wealthier and more likely to access private services. However, other factors may also be important. One study showed that health care workers in Srinagar (India) believed that influenza vaccine was harmful and they did not prescribe it.12 This barrier was successfully tackled through targeted education campaigns, suggesting that in places where availability of vaccines are not an issue, local determinants should be investigated and addressed.

Our analyses are based on data collected following highly standardised protocols and quality controlled methods. The LMIC data (except for China and Turkey) were collected after 2008 and our results are in line with other quoted reports but local treatment guidelines or public health budgets might have changed since. Response to the survey was high, 80% on average, and the characteristics of the non-responders did not significantly differ from those of responders for demographics and doctor-diagnosed chronic respiratory disease. We acknowledge that in a study relying for some measures on self-reports, some recall error is inevitable and some recall bias is possible. However, we have asked very specific questions on ‘regular use of medications for breathing’ with much more detailed questions on the type and use of the medicines remembered. It is unlikely that differential reporting could explain the main findings.

Conclusion

The use of bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids and influenza vaccine is higher in HICs than in LMICs when adjusted for similar clinical need and is strongly associated with the gross national product per capita for the country. Although the financial ability to purchase medication is an important constraint, often not documented, affordability alone is not the only determinant to be considered for changing trends in use of selected essential medicines. There are likely to be many other local factors and barriers, including some associated with poverty, that are likely to influence uptake. Knowledge, awareness and attitudes, both of patients and health professionals, as well as health systems are some examples to be considered by policy makers. By identifying and addressing these in a more systematic and specific way, to what is locally relevant, major improvements can be expected in access and use of effective treatments. Better understanding of factors affecting low uptake at individual level and improving access to those medicines, particularly in LMICs, remains important.

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgements. The BOLD initiative has been funded in part by unrestricted educational grants to the Operations Center from ALTANA, Aventis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, and University of Kentucky. The Co-ordination of the BOLD initiative by Imperial College London is funded by the Wellcome Trust (085790/Z/08/Z) since December 2008.

The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Additional local support for BOLD clinical sites

Additional local support for BOLD clinical sites was provided by: Boehringer Ingelheim China. (GuangZhou, China ); Turkish Thoracic Society, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer (Adana, Turkey); Altana, Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Novartis, Salzburger Gebietskrankenkasse and Salzburg Local Government (Salzburg, Austria ); Research for International Tobacco Control, the International Development Research Centre, the South African Medical Research Council, the South African Thoracic Society GlaxoSmithKline Pulmonary Research Fellowship, and the University of Cape Town Lung Institute (Cape Town, South Africa ); and Landspítali-University Hospital-Scientific Fund, GlaxoSmithKline Iceland, and AstraZeneca Iceland (Reykjavik, Iceland ); GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Polpharma, Ivax Pharma Poland, AstraZeneca Pharma Poland, ZF Altana Pharma, Pliva Kraków, Adamed, Novartis Poland, Linde Gaz Polska, Lek Polska, Tarchomińskie Zakłady Farmaceutyczne Polfa, Starostwo Proszowice, Skanska, Zasada, Agencja Mienia Wojskowego w Krakowie, Telekomunikacja Polska, Biernacki, Biogran, Amplus Bucki, Skrzydlewski, Sotwin, and Agroplon (Krakow, Poland); Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Pfizer Germany (Hannover, Germany ); the Norwegian Ministry of Health’s Foundation for Clinical Research, and Haukeland University Hospital’s Medical Research Foundation for Thoracic Medicine (Bergen, Norway); AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline (Vancouver, Canada); Marty Driesler Cancer Project (Lexington, Kentucky, USA); Altana, Boehringer Ingelheim (Phil), GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Philippine College of Physicians, and United Laboratories (Phil) (Manila, Philippines); Air Liquide Healthcare P/L, AstraZeneca P/L, Boehringer Ingelheim P/L, GlaxoSmithKline Australia P/L, Pfizer Australia P/L (Sydney, Australia), Department of Health Policy Research Programme, Clement Clarke International (London, United Kingdom); Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer (Lisbon, Portugal), Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, The Swedish Association against Heart and Lung Diseases, Glaxo Smith Kline (Uppsala, Sweden); GlaxoSmithKline, Astra Zeneca, Eesti Teadusfond (Estonian Science Foundation) (Tartu, Estonia); AstraZeneca, CIRO HORN (Maastricht, The Netherlands); Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, J&K (Srinagar, India); Foundation for Environmental Medicine, Kasturba Hospital, Volkart Foundation (Mumbai, India); Boehringer Ingelheim (Sousse, Tunisia); Boehringer Ingelheim (Fes, Morocco); Philippines College of Physicians, Philippines College of Chest Physicians, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Orient Euro Pharma, Otsuka Pharma, United laboratories Phillipines (Nampicuan&Talugtug, Philippines); National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London (Pune, India); The Wellcome Trust, National Population Commission, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria (Ile-Ife, Nigeria).

The BOLD Collaboration

A Sonia Buist, William Vollmer, Suzanne Gillespie, MaryAnn McBurnie (BOLD Co-ordinating Centre, Kaiser Permanente, Portland, USA), Peter GJ Burney, Bernet Kato, Louisa Gnatiuc, Anamika Jithoo, Sonia Coton, Hadia Azhar (BOLD Co-ordinating Centre, Imperial College London, UK), NanShan Zhong (PI), Shengming Liu, Jiachun Lu, Pixin Ran, Dali Wang, Jingping Zheng, Yumin Zhou (Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Guangzhou Medical College, Guangzhou, China); Ali Kocabaş (PI), Attila Hancioglu, Ismail Hanta, Sedat Kuleci, Ahmet Sinan Turkyilmaz, Sema Umut, Turgay Unalan (Cukurova University School of Medicine, Department of Chest Diseases, Adana, Turkey); Michael Studnicka (PI), Torkil Dawes, Bernd Lamprecht, Lea Schirhofer (Paracelsus Medical University, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Salzburg Austria); Eric Bateman (PI), Anamika Jithoo (PI), Desiree Adams, Edward Barnes, Jasper Freeman, Anton Hayes, Sipho Hlengwa, Christine Johannisen, Mariana Koopman, Innocentia Louw, Ina Ludick, Alta Olckers, Johanna Ryck, Janita Storbeck, (University of Cape Town Lung Institute, Cape Town, South Africa); Thorarinn Gislason (PI), Bryndis Benedikdtsdottir, Kristin Jörundsdottir, Lovisa Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun Gudmundsdottir, Gunnar Gundmundsson, (Landspitali University Hospital, Dept. of Allergy, Respiratory Medicine and Sleep, Reykjavik, Iceland); Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka (PI), Jakub Frey, Rafal Harat, Filip Mejza, Pawel Nastalek, Andrzej Pajak, Wojciech Skucha, Andrzej Szczeklik,Magda Twardowska, (Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University School of Medicine, Cracow, Poland); Tobias Welte (PI), Isabelle Bodemann, Henning Geldmacher, Alexandra Schweda-Linow (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany); Amund Gulsvik (PI), Tina Endresen, Lene Svendsen (Department of Thoracic Medicine, Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway); Wan C. Tan (PI), Wen Wang (iCapture Center for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada); David M. Mannino (PI), John Cain, Rebecca Copeland, Dana Hazen, Jennifer Methvin, (University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA); Renato B. Dantes (PI), Lourdes Amarillo, Lakan U. Berratio, Lenora C. Fernandez, Norberto A. Francisco, Gerard S. Garcia, Teresita S. de Guia, Luisito F. Idolor, Sullian S. Naval, Thessa Reyes, Camilo C. Roa, Jr., Ma. Flordeliza Sanchez, Leander P. Simpao (Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Manila, Philippines); Christine Jenkins (PI), Guy Marks (PI), Tessa Bird, Paola Espinel, Kate Hardaker, Brett Toelle (Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, Australia), Peter GJ Burney (PI), Caron Amor, James Potts, Michael Tumilty, Fiona McLean (National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London), E.F.M. Wouters, G.J. Wesseling (Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands), Cristina Bárbara (PI), Fátima Rodrigues, Hermínia Dias, João Cardoso, João Almeida, Maria João Matos, Paula Simão, Moutinho Santos, Reis Ferreira (The Portuguese Society of Pneumology, Lisbon, Portugal), Christer Janson (PI), Inga Sif Olafsdottir, Katarina Nisser, Ulrike Spetz-Nyström, Gunilla Hägg and Gun-Marie Lund (Department of Medical Sciences: Respiratory Medicine & Allergology, Uppsala University, Sweden), Rain Jõgi (PI), Hendrik Laja, Katrin Ulst, Vappu Zobel, Toomas-Julius Lill (Lung Clinic, Tartu University Hospital), Parvaiz A Koul (PI), Sajjad Malik, Nissar A Hakim, Umar Hafiz Khan (Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, J&K, India); Rohini Chowgule (PI) Vasant Shetye, Jonelle Raphael, Rosel Almeda, Mahesh Tawde, Rafiq Tadvi, Sunil Katkar, Milind Kadam, Rupesh Dhanawade, Umesh Ghurup (Indian Institute of Environmental Medicine, Mumbai, India); Imed Harrabi (PI), Myriam Denguezli, Zouhair Tabka, Hager Daldoul, Zaki Boukheroufa, Firas Chouikha, Wahbi Belhaj Khalifa (Faculté de Médecine, Sousse, Tunisia); Luisito F. Idolor (PI), Teresita S. de Guia, Norberto A. Francisco, Camilo C. Roa, Fernando G. Ayuyao, Cecil Z.Tady, Daniel T. Tan, Sylvia Banal-Yang, Vincent M. Balanag, Jr., Maria Teresita N. Reyes, Renato. B. Dantes (Lung Centre of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Nampicuan&Talugtug, Philippines); Sundeep Salvi (PI), Sundeep Salvi (PI), Siddhi Hirve, Bill Brashier, Jyoti Londhe, Sapna Madas, Somnath Sambhudas, Bharat Chaidhary, Meera Tambe, Savita Pingale, Arati Umap, Archana Umap, Nitin Shelar, Sampada Devchakke, Sharda Chaudhary, Suvarna Bondre, Savita Walke, Ashleshsa Gawhane, Anil Sapkal, Rupali Argade, Vijay Gaikwad (Vadu HDSS, KEM Hospital Research Centre Pune, Chest Research Foundation (CRF), Pune India); Mohamed C Benjelloun (PI), Chakib Nejjari, Mohamed Elbiaze, Karima El Rhazi (Laboratoire d’épidémiologie, Recherche Clinique et Santé Communautaire, Fès, Morroco); Daniel Obaseki (PI), Gregory Erhabor, Olayemi Awopeju, Olufemi Adewole (Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria)

References

- 1.Jafarov A, Schneider T, Waning B, Hems S, van den Ham R, Ma E, Wang LJ, Laing R. Comparative Table of Core and Complementary Medicines on the WHO Essential Medicines List from 1977- 2011. World Health Organisation; Geneva: [as at 21 Nov2011]. 2011. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laing R, Waning B, Gray A, Ford N, ’t Hoen E. 25 years of the WHO essential medicines lists: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2003 May 17;361(9370):1723–1729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [accessed 13 February 2013];Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2011 http://www.goldcopd.org/uploads/users/files/GOLD2011_Summary.pdf.

- 4.The Global Initiative for Asthma. Pocket Guide for Asthma Management and Prevention; [accessed 13 February 2013]. http://www.ginasthma.org/uploads/users/files/GINA%20Pocket%20Guide%202012_wms.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ait-Khaled N, Auregan G, Bencharif N, Camara LM, Dagli E, Djankine K, et al. Affordability of inhaled corticosteroids as a potential barrier to treatment of asthma in some developing countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000 Mar;4(3):268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendis S, Fukino K, Cameron A, Laing R, Filipe A, Jr, Khatib O, Leowski J, Ewen M. The availability and affordability of selected essential medicines for chronic diseases in six low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin World Health Organisation. 2007 Apr;85(4):279–88. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.033647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron A, Ewen M, Ross-Degnan D, Ball D, Laing R. Medicine prices, availability, and affordability in 36 developing and middle-income countries: a secondary analysis. Lancet. 2009 Jan 17;373(9659):240–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61762-6. Epub 2008 Nov 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babar ZUD, Lessing C, Mace C, Bissell K. The Availability, Pricing and Affordability of Three Essential Asthma Medicines in 52 Low- and Middle-Income Countries. PharmacoEconomics. 31(11):1063–1082. doi: 10.1007/s40273-013-0095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poole P, Chacko EE, Wood-Baker R, Cates CJ. Influenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Review) The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library. 2010;(Issue 8) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cates CJ, Jefferson TO, Rowe BH. Vaccines for preventing influenza in people with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Apr 16;(2):CD000364. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000364.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santos-Sancho JM, Jimenez-Trujillo I, Hernández-Barrera V, López-de Andrés A, Carrasco-Garrido P, Ortega-Molina P, Jiménez-García R. Influenza vaccination coverage and uptake predictors among Spanish adults suffering COPD. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012 Jul;8(7):938–45. doi: 10.4161/hv.20204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bali NK, Ashraf M, Ahmad F, Khan UH, Widdowson MA, Lal RB, Koul PA. Knowledge, attitude, and practices about the seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in Srinagar, India. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2012 Aug 2; doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00416.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Sullivan SD, Weiss KB, Lee TA, Menezes AM, Crapo RO, Jensen RL, Burney PG. The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD. 2(2):277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. [Accessed April 20, 2009];Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2008 http://www.goldcopd.org.

- 16.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319–338. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cazzola M, MacNee W, Martinez FJ, Rabe KF, Franciosi LG, Barnes PJ, et al. Outcomes for COPD pharmacological trials: from lung function to biomarkers. Eur Respir J. 2008 Feb;31(2):416–469. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00099306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials. 7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Development Indicators database, World Bank, Gross National Income per capita Indicators (Atlas method, International current US$,2010) accessed at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD.

- 21.Burney P, Potts J, Aït-Khaled N, Sepulveda RM, Zidouni N, Benali R, Jerray M, Musa OA, El-Sony A, Behbehani N, El-Sharif N, Mohammad Y, Khouri A, Paralija B, Eiser N, Fitzgerald M, Abu-Laban R. A multinational study of treatment failures in asthma management. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008 Jan;12(1):13–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. Global Asthma Report. 2011 accessed at http://www.globalasthmareport.org/

- 23.The Norwegian Directorate of Health: Nasjonal faglig retningslinje og veileder for diagnostisering og oppfølgning av personer med kols. Helsedirektoratet. 2012 Available from http://www.helsedirektoratet.no/publikasjoner/nasjonal-faglig-retningslinje-og-veileder-for-forebygging-diagnostisering-og-oppfolging-av-personer-med-kols/Sider/default.aspx.

- 24.Nielsen R, Johannessen A, Benediktsdottir B, Gislason T, Buist AS, Gulsvik A, Sullivan SD, Lee TA. Present and future costs of COPD in Iceland and Norway: Results from the BOLD study. Eur Respir J. 2009 Oct;34(4):850–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00166108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppel A, Kahur K, Habicht T, Saar P, Habicht J, van Ginneken E. Estonia: Health system review. Health Systems in Transition. 2008;10(1):1–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koul PA. Managing chronic diseases: combination of inhaler treatment in India has shown good results. BMJ. 2005 Apr 23;330(7497):964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7497.964-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jawla S, Gupta AK, Singla R, Gupta V. General awareness and relative popularity of allopathic, ayurvedic and homeopathic systems. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research. 2009;1(1):105–11. [Google Scholar]