Abstract

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy is characterized by clubbing and periosteal new bone formation along the shaft of the long bones of the extremities. Although various intrathoracic malignancies have been associated with the development of HOA, it has been extremely rare for HOA to occur in a patient with a thymic carcinoma. Recently, we experienced a 63-year-old woman diagnosed as a thymic carcinoma with hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. She had both digital clubbing and cortical thickening in her lower extremities identified radiologically. We herein describe this case with a review of the literature.

Keywords: Hypertrophic Osteoarthropathy (HOA), Thymic Cancer

INTRODUCTION

Clubbing of digits, periosteal new bone formation along the shafts of the tubular bones of the extremities and synovial effusions characterize hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA)1). HOA is divided into two basic types, primary and secondary. Primary HOA is a rare syndrome, not associated with other systemic diseases, and usually occurs in childhood, whereas secondary HOA is associated with various underlying pulmonary and non-pulmonary causes, such as bronchogenic carcinoma and right-to-left cardiac shunts.

Although various intrathoracic malignancies have been associated with the development of HOA, it has been extremely rare for HOA to occur in a patient with a malignant neoplasm of the thymus. Since the first case was reported in 19392), a few cases have been reported worldwide3, 4). Recently, we experienced a case of HOA with a thymic carcinoma, and herein report the case with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old woman was referred to our hospital because she had a chief complaint of both leg pains. The pain was noted several months ago without any prior history, such as trauma and it was wax and wane and slowly progressing. She did not have any other systemic symptoms, such as weight loss or fever. She was a nonsmoker and did not drink alcohol. She had never been exposed to toxic or irritating substances. Her past and family history was not contributory except for the diagnosis of hypertension one year before and antihypertensive medication thereafter.

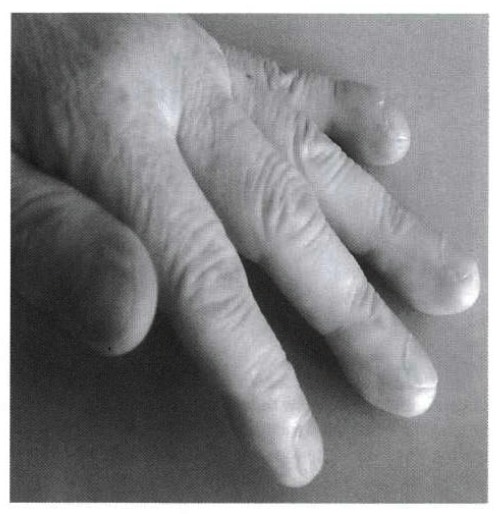

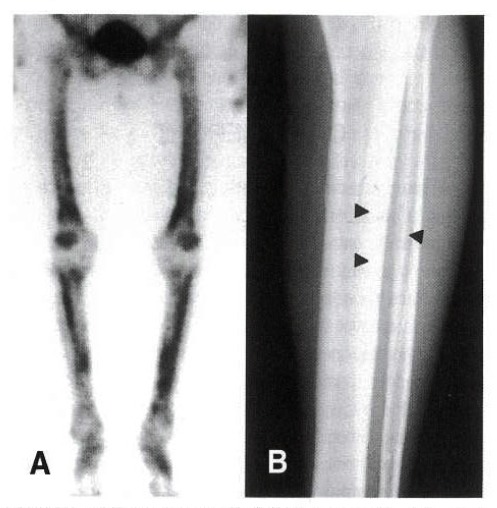

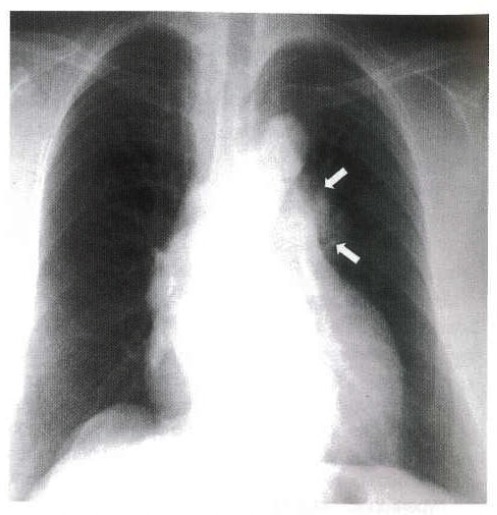

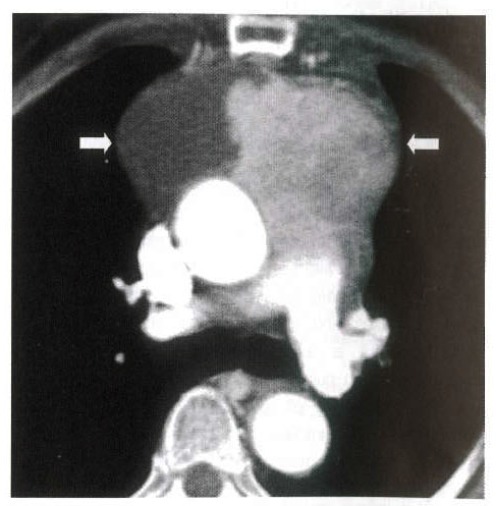

Physical examination at presentation was normal except for tenderness of both the lower extremities and clubbing of the fingers (Figure 1). Laboratory investigation showed no abnormal findings except for mild anemia (Hgb 10.2 g/dL). The plain radiograph of both lower legs showed cortical thickening along the shaft of the tibia and the bone scan revealed diffusely increased uptake along the cortex of both lower extremities (Figure 2). The radiologic findings were not consistent with bone metastasis but with hypertrophic osteo arthropathy (HOA). In order to find the possibility of the secondary HOA, we performed a chest radiograph, which revealed a left mediastinal bulging mass (Figure 3). The chest CT scan confirmed the presence of a soft tissue density mass in the anterior mediastinum with pericardial effusion (Figure 4). For a pathologic confirmation, ultrasound-guided needle biopsy was done on the anterior mediastinal mass. Microscopic examination showed irregular nests of poorly differentiated malignant cells with hyperchromatic and irregular nuclei (Figure 5). According to the microscopic examination, a diagnosis of poorly differentiated thymic carcinoma was made. Thus, we finally diagnosed the patient as a thymic carcinoma with HOA.

Figure 1.

Clubbing of fingers.

Figure 2.

(A) Bone scan shows diffusely increased uptake along the cortical portions of both lower extremities. (B) Left tibia and fibular X-ray films demonstrate diffuse cortical thickening (arrows).

Figure 3.

Chest PA view shows left mediastinal bulging (arrows).

Figure 4.

At carinal level, chest CT scan shows a heterogeneous enhancing mass (arrows) with pericardial effusion in anterior mediastinum.

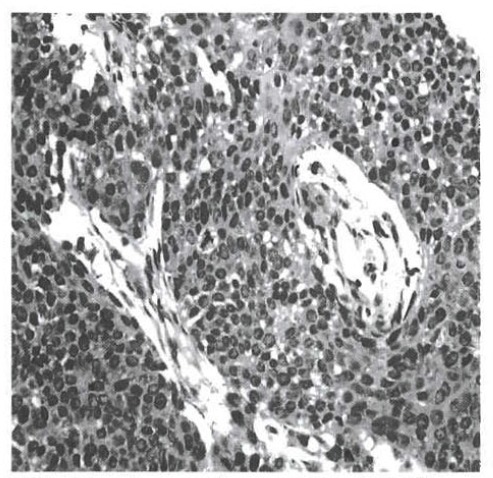

Figure 5.

Irregular nests of malignant tumor cells with some necrotic area. Tumor cells show poorly differentiated appearance with hyperchromatic and irregular nuclei and moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic figures are frequently seen (Hematoxylin & Eosin, ×200).

DISCUSSION

Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (HOA) begins as periostitis followed by new bone formation, which is seen as a solid lamination involving the proximal and distal diaphyses of the tibia, fibula, radius, ulna and, less frequently, the femur, humerus, metacarpals, metatarsals and phalanges. As the process of new bone formation progresses, these changes extend to involve metaphyses. The distribution of the bone involvement is usually bilateral and symmetric. These changes are more apparent distal to the knees and elbows. Initial radiological finding is a radiolucent area between the new bone formation and subjacent cortex. In the long-standing process, multiple layers of newly formed bone are deposited and cause cortical thickening. Para-cortical increase of uptake is a characteristic finding of the bone scan study5). Proliferation of connective tissue occurs in the nail bed and volar pad of the digits, giving rise to clubbing. Clubbing is almost always a feature of HOA but can occur as an isolated manifestation. This isolated manifestation of clubbing may represent an early stage of HOA, so it may have the same clinical significance as HOA.

Secondary HOA occurs in association with a variety of underlying disorders, including heart, lungs, pleura, gastrointestinal tract and liver. Although several theories have been suggested for the pathogenesis of HOA, its underlying mechanism is still controversial. However, a number of plausible theories have been proposed1). Among these, one hypothesis is the megakaryocyte/platelet clump hypothesis6). Normally, megakaryocytes are transported to the lung via venous circulation from the bone marrow. Then, most platelets are produced in the lungs, especially, in pulmonary capillaries, by physical fragmentation of cytoplasms of megakaryocytes7), because they are large and cannot pass unchanged through the normal lung vasculature, which is narrow. In patients with disorders associated with right-to-left shunts, such as cyanotic congenital heart disease and severe liver cirrhosis (where the pulmonary circulation is abnormal due to the development of arteriovenous connections in the lungs), these megakaryocytes and large platelet particles may bypass the lung and reach the distal extremities, leading to the interaction with endothelial cells. This interaction in the distal portion of extremities would then result in degranulation and the production of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and other factors, causing proliferation of connective tissue and periosteum8).

HOA has been associated with many different benign and malignant intrathoracic tumors and occurs in 5–10% of patients with intrathoracic malignancies including lung cancer and pleural tumors1). The most frequently associated cancer is non-small cell lung cancer9). In these situations, the tumor itself may supply a vascular shunt from right to left without being filtered through pulmonary capillaries. In addition, platelet function may be altered in lung cancer10). Megakaryocytes are larger in lung cancer than normal and may have increased PDGF synthetic activity.

The relatively frequent association of HOA with lung cancers suggests that some additional factors may be involved in the development of HOA in lung cancer. Growth hormone secretion by bronchogenic carcinoma was suggested for the underlying mechanism of the occurrence of HOA and clubbing11). Mito et al. reported an elevated serum growth hormone level and growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH)-producing cells in a non-small lung cancer patient with HOA12).

Recently, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been implicated in the pathogenesis of HOA. Silveira et al. reported that plasma levels of VEGF were significantly higher in patients with primary HOA and in those with lung cancer associated with HOA, compared with healthy control. In addition, serum VEGF levels were higher in patients with lung cancer and HOA compared with lung cancer patients without HOA13).

Thymic carcinoma is a rare epithelial neoplasm of the thymus that has a poor prognosis. In the past, malignant thymoma included invasive thymoma and thymic carcinoma. Invasive thymoma has a similar cytological feature to benign thymoma but thymic carcinoma exhibits malignant cytological features. The majority of thymic carcinoma is squamous cell carcinoma either well or poorly differentiated14). The present patient was diagnosed as a poorly differentiated thymic carcinoma.

There has been no explanation for the mechanism of the coexistence of thymic carcinoma and HOA. However, some reports suggest possible mechanisms. Sasaki et al. reported that serum levels of VEGF and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were significantly elevated in patients with thymic carcinoma compared with those in healthy volunteers15). Therefore, the results suggested that serum VEGF and bFGF might serve as markers for thymic carcinoma and these angiogenic factors could be associated with the invasiveness of thymic carcinoma. On the other hand, Lauriola et al. observed the presence of growth hormone-producing cells in patients with thymoma16). Thus, we measured the serum level of VEGF in the patient by using human VEGF ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire, UK). Serum VEGF level was elevated in the patient (1,120 pg/mL) compared with the mean value of healthy volunteers (388 ± 68.9 pg/mL). We also measured the serum level of the growth hormone in the patient. Although it might not have significance because provocation and suppression tests were not done, the serum level of the growth hormone (5.6 ug/L) was not increased compared with a normal control value (<10 ug/L). However, further study is warranted to evaluate the mechanism of HOA and the relationship between HOA and thymic carcinoma.

The patient was initially treated with external radiation therapy because of poor resectability and increased operative risk. The size of the mass was significantly decreased after completion of radiation therapy. However, new metastatic brain lesion was observed in a brain MRI that was performed when the patient complained of neurologic symptoms. Brain metastasis was known to be rare in thymic carcinoma, so it was also an unusual presentation of thymic carcinoma. Because high serum VEGF has been known to relate with metastasis and invasiveness of cancer and poor clinical outcome, brain metastasis might be associated with elevated serum VEGF in the patient. Considering the possible relationship between serum VEGF and the development of HOA, it may be suggested that HOA could be a poor prognostic sign in thymic carcinoma. In summary, we experienced a rare case of poorly differentiated thymic carcinoma associated with HOA and suggest a possible association between thymic carcinoma and HOA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilliland BC. Relapsing polychondiritis and other arthritides. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2005–2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RR. Carcinoma of the thymus with marked pulmonary osteoarthropathy. Radiology. 1939;32:651. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesser M, Mouli CC, Jothikumar T. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy associated with a malignant thymoma. Mt Sinai J Med. 1980;47:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gharbi A, Benjelloun A, Ouzidane L, Ksiyer M. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy associated with malignant thymoma in a child. J Radiol. 1997;78:303–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yochum TR, Rowe LJ. Essentials of skeletal radiology. 2nd ed. Maryland: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 925–929. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickinson CJ. The aetiology of clubbing and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Eur J Clin Invest. 1993;23:330–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1993.tb02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen N. The pulmonary vessels as a filter for circulating megakaryocytes in rats Scand. J Haematol. 1974;13:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1974.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sridhar KS, Lobo CF, Altman RD. Digital clubbing and lung cancer. Chest. 1998;114:1535–1537. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.6.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segal AM, Mackenzie AH. Hypertrophic osteoarthropathy: a 10-year retrospective analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1982;12:220. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(82)90062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kristensen SD, Bath PM, Gladwin AM, Martin JF. The relationship between increased platelet count and megakaryocyte size in bronchial carcinoma. Br J Haematol. 1992;81:247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1992.tb08215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gosney MA, Gosney JR, Lye M. Plasma growth hormone and digital clubbing in carcinoma of the bronchus. Thorax. 1990;45:545. doi: 10.1136/thx.45.7.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mito K, Maruyama R, Uenishi Y, Arita K, Kawano H, Kashima K, Nasu M. Hypertrophic pulmonary osteoarthropathy associated with non-small cell lung cancer demonstrated growth hormone-releasing hormone by immunohistochemical analysis. Intern Med. 2001;40:532–535. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.40.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silveira LH, Martinez-Lavin M, Pineda C, Fonseca MC, Navarro C, Nava A. Vascular endothelial growth factor and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cameron RB, Loehrer PJ, Thomas CR., Jr . Neoplasms of the mediastinum. In: Devita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer principles & Practice of Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 1019–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki H, Yukiue H, Kobayashi Y, Nakashima Y, Moriyama S, Kaji M, Kiriyama M, Fukai I, Yamakawa Y, Fujii Y. Elevated serum vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor levels in patients with thymic epithelial neoplasms. Surg Today. 2001;31:1038–1040. doi: 10.1007/s005950170021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lauriola L, Maggiano N, Serra FG, Nori S, Tardio ML, Capelli A, Piantelli M, Ranelletti FO. Immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization detection of growth-hormone-producing cells in human thymoma. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:55–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]