Abstract

Dermatomyositis in pregnancy is rare. Pregnancy may be a precipitating factor at the onset or may develop during the course of dermatomyositis, which would exacerbate disease activity. In this study, we report a 22-year-old female patient who developed generalized skin rash and progressive muscle weakness in the twelfth week of pregnancy. She was diagnosed with dermatomyositis and underwent therapeutic abortion, due to the high fetal mortality rate of the disease when developed in the first trimester. Her symptoms improved with treatment of intravenous immunoglobulin and a high dose of corticosteroids.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, Pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Dermatomyositis is a rare autoimmune disease with an incidence rate of one per a population of one million1). Only 14% of cases occur during child-bearing years2), and only a few cases of dermatomyositis associated to pregnancy complications have been reported3). Therefore there is relatively little information concerning the maternal and fetal outcome. We report a patient diagnosed with dermatomyositis in the first trimester of pregnancy. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of a patient with dermatomyositis during pregnancy in Korea, who was successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and a high dose of corticosteroids after therapeutic abortion.

CASE REPORT

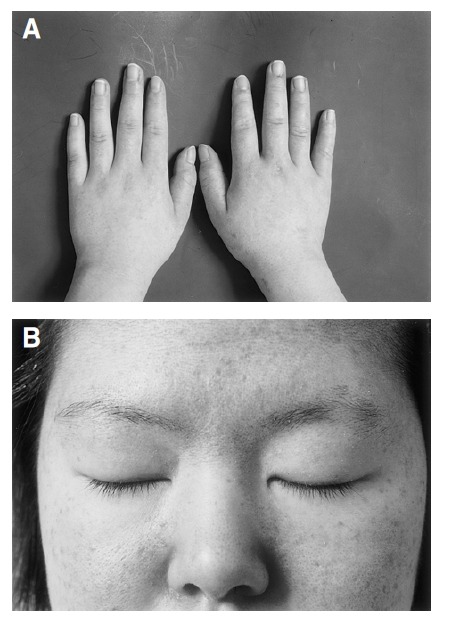

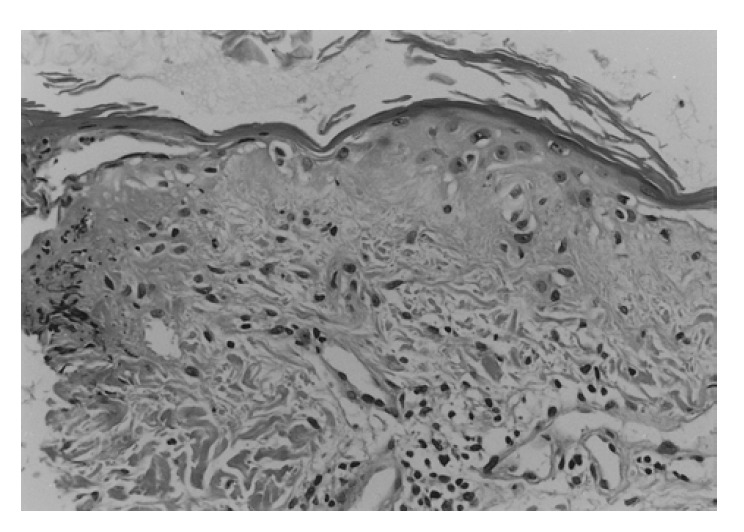

A 22-year-old Korean woman in the twelfth week of her second pregnancy was referred from the dermatology department as she developed symptoms of generalized weakness and skin rash. She had a past history of spontaneous abortion. Fourteen weeks ago, she had noticed facial swelling and edema in both legs. She also had a 12-week history of generalized myalgia and a 10-week history of generalized weakness. She had been bed-ridden for eight weeks. On admission, she complained of anorexia, nausea, and generalized itching. Physical examination of the patient revealed moderate facial and peripheral edema, a generalized erythematous rash with discoloration on the face, neck, trunk, buttock, both arms and knees. The typical Gottron’s papules (Figure 1A), periungual telangiectasia, and periorbital heliotrope rash were also observed (Figure 1B). Blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg and pulse rate was 128 beats/min. Neurologic examination showed grade 2 proximal muscle weakness in both arms and legs and remarkable muscle tenderness. Complete blood counts, electrolyte, urinalysis and thyroid function test were normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated to 65 mm/hr. Muscle enzymes were elevated with creatine kinase at 245 IU/L (normal, 30–180 IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase at 67 IU/L (normal, 5–40 IU/L), lactic dehydrogenase at 422 IU/L (normal, 100–220 IU/L). Antinuclear antibody titer was 1:80 (homogenous type), but anti-RNP, anti-dsDNA, and rheumatoid factor were negative. Electromyographic examination showed bizarre high-frequency discharges, repetitive fibrillations and a decrease in the amplitude and duration of the motor action potentials. Nerve conduction studies were normal. Skin biopsy revealed an atrophic epidermis and hydropic degeneration of the basal keratinocyte associated with a few perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations (Figure 2). There were areas of subepidermal fibrin deposition. Direct immunofluorescence was negative. We could not obtain muscle biopsy due to the patient’s refusal. We decided to have an abortion due to profound muscle weakness and high fetal mortality in patients that develop dermatomyositis in the first trimester. She had multiple skin abrasions on the neck, bilateral arms, knees, and buttocks. There was also a wound infection on the chest wall. We began therapy with intravenous and topical antibiotics. In addition, we began medication of IVIG (2 g/kg divided into 5 days) instead of steroid due to skin infection. She improved slowly and was discharged 10 days after IVIG therapy. On discharge the patient was well, with improved limb weakness. Her proximal muscle weakness was graded as 5/5, which was an improvement from 2/5 at admission. The skin wound and rash took longer to clear, and she no longer required topical treatment 30 days later. Therefore, we decided to start prednisolone therapy at 60 mg daily. She was treated with IVIG (1 g/kg for 1 day) every 4 weeks repeatedly. After 8 weeks, muscle enzymes returned to normal, and we reduced prednisolone to 30 mg daily.

Figure 1.

Skin lesions of the patient. (A) Gottron’s papule on both knuckles. (B) Heliotrope rash on both upper eyelids.

Figure 2.

Microscopic finding of skin biopsy (H&E, ×200): An atrophic epidermis shows basement membrane degeneration, vacuolar alteration of basal keratinocytes with focal subepidermal fibrin deposition.

DISCUSSION

Dermatomyositis is classified as idiopathic inflammatory myopathy4). Women are affected twice as often as men and, in adults, the peak incidence occurs in the fifth decade, although all age groups may be affected5). Only a few cases of dermatomyositis have involved complications in pregnancy3). Consequently, there is relatively little information concerning the outcome of pregnancy. Fetal morbidity and mortality are substantial and seem to parallel maternal disease activity. Stillbirth or neonatal death complicated pregnancies in 7 of 15 patients with active disease6). Even in patients that have the disease under control with treatment, pregnancy may result in fetal death (3 of 14) or prematurity (3 of 14). There are no consistent fetal or placental abnormalities to explain the degree of mortality and prematurity. When disease onset is in the first trimester, fetal mortality is very high (83%), and even with onset in the second or third trimester, the risk for premature delivery remains high, although no infant has died in such a circumstance7, 8). Fifty percent of previously reported cases of dermatomyositis began during the first trimester of pregnancy9), as in the present case. These data allow us to consider pregnancy as a precipitating factor at the onset and in the exacerbation of dermatomyositis, and strongly advises a close follow-up of the mother for early detection of disease flare-ups and timely treatment9). The rapid response after abortion in this patient suggests that pregnancy might have triggered the disease. A hypothesis suggesting a role for viral infection in the development of dermatomyositis, and a decrease in the humoral response to certain viral antigens during pregnancy has been suggested to provide the link between dermatomyositis and pregnancy2).

Dermatomyositis responds to steroids but often becomes steroid-resistant, and some patients find the steroid side effects unbearable. In a double-blind study of patients with refractory dermatomyositis, IVIG improved not only muscle strength and skin rash, but also the underlying immunopathology10–12). Repeated open muscle biopsies of patients who improved clinically have shown marked improvement in the muscle cytoarchitecture, including muscle fiber diameter, revascularization with increased number of capillaries per fiber, and reduction of inflammation and connective tissue12). The improvement in strength does not last more than 4–8 weeks, and repeated infusions are required periodically to maintain it12). Some patients with dermatomyositis who had become unresponsive to steroids may respond again to prednisolone after IVIG infusion13). Since dermatomyositis responds to steroids, IVIG therapy is best reserved for steroid-resistant patients, for patients not adequately controlled with combinations of steroids and methotrexate or azathioprine (as a third-line add-on), and for patients who are immunodeficient or in whom steroids and immunosuppressants are contraindicated. We repeated IVIG infusions every 4 to 6 weeks for maintenance therapy.

Our case and previous data allow us to consider pregnancy as a precipitating factor at the onset and in the exacerbation of dermatomyositis2, 9). Therefore complaints of muscle weakness and fatigue should not be dismissed as symptoms pregnancy alone. Complaints of muscle weakness, fatigue, skin rash and edema should be investigated by evaluation of muscle strength and determination of creatine kinase. Pregnancy associated with dermatomyositis should be considered as a high-risk. We believe that better understanding of this association, together with improvements in maternal and fetal monitoring and care will result in better prognosis for fetal outcome.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banker BQ, Engel AG. The polymyositis and dermatomyositis syndromes. In: Engel AG, Banker BQ, editors. Myology. 1st eds. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1986. pp. 1385–1422. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinheiro Gda R, Goldenberg J, Atra E, Pereira RB, Camano L, Schmidt B. Juvenile dermatomyositis and pregnancy. Report and literature review. J Rheumatol. 1992;19:1798–1801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kofteridis DP, Malliotakis PI, Sotsiou F, Vardakis NK, Vamvakas LN, Emmanouel DS. Acute onset of dermatomyositis presenting in pregnancy with rhabdomyolysis and fetal loss. Scand J Rheumatol. 1999;28:192–194. doi: 10.1080/03009749950154301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalakas MC. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis, and inclusion-body myositis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1487–1498. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tymms KE, Webb J. Dermatopolymyositis and other connective tissue diseases: A review of 105 cases. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:1140–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishii N, Ono H, Kawaguchi T, Nakajima H. Dermatomyositis and pregnancy. Case report and review of the literature. Dermatologica. 1991;183:146–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanoh H, Izumi T, Seishima M, Nojiri M, Ichiki Y, Kitajima Y. A case of dermatomyositis that developed after delivery: the involvement of pregnancy in the induction of dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:897–900. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MJ. Obstetric complications and rheumatic disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23:169–182. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gutierrez G, Dagnino R, Mintz G. Polymyositis/dermatomyositis and pregnancy. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:291–294. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalakas MC. Immunopathogenesis of inflammatory myopathies. Ann Neurol. 1995;37(suppl):74–86. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basta M, Kirshbom P, Frank MM, Fires LF. Mechanisms of therapeutic effect of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1974–1981. doi: 10.1172/JCI114387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalakas MC, Illa I, Dambrosia JM, Soueidan SA, Stein DP, Otero C. A controlled trial of high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin infusion as treatment of dermatomyositis. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1993–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dalakas MC. Intravenous immunoglobulin in the treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular diseases: Present status and practical therapeutic guidelines. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:1479–1497. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199911)22:11<1479::aid-mus3>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]