Abstract

Actinomycosis is a slowly progressive infectious disease caused by an anaerobic and microaerophilic bacteria that colonizes the face, neck, lung, pleura and the ileocecal region.

There have been a few cases of this disease which have involved in the lung but one very rare case has been reported. We report a case of foreign body-induced endobronchial actinomycosis mimicking bronchogenic carcinoma in a 69-year-old man. On admission, the patient presented with weight loss, cough and hemoptysis. The fiberoptic bronchoscopy revealed a soft tissue mass, with a partial occlusion of the left upper bronchus, which resembled bronchogenic carcinoma. Contrary to the first impression, the biopsy of the bronchus revealed the mass lesion to be an actinomycotic infection involving the bronchus. After the confirmation of the lesion, treatment with penicillin was initiated. The follow-up bronchoscopy revealed an aspirated fish bone at the site of infection. The foreign body was safely removed.

Keywords: Actinomycosis, Foreign bodies, Carcinoma, Bronchogenic

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary infection due to Actinomyces species is very uncommon but can result from aspiration of oropharyngeal secretions, direct extension from cervicofacial infection or hematogenous dissemination from a distant focus or aspiration of a foreign body (e.g., chicken bone)1–5). In most cases, the presenting manifestations of actinomycosis are unresolved pneumonia, pulmonary infiltration or mass-like lesion on routine chest radiographs. Endobronchial actinomycosis is a rare case and may be misdiagnosed as bronchogenic carcinoma and endobronchial tuberculosis. We present a very rare case of foreign body-induced endobronchial actinomycosis which resembled bronchogenic carcinoma initially and was confirmed by bronchial biopsy.

CASE

In April 2000, a 69-year-old man was admitted to Inha General Hospital due to productive cough with dark, brown-colored sputum. He complained of night sweat and weight loss of more than 9 killograms for 2 months. Nine years before entry, the patient experienced a cerebrovascular accident which left a sequelae of left side weakness, mild dysphagia and dysarthria. Because of poor oral hygiene, plaque and calculus, the patient had frequent visits to the dentist but no dental care was given within the previous 5 years. The patient had no past medical history of pulmonary tuberculosis, chronic lung disease or any other condition.

On physical examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 130/90 mmHg, pulse rate 80/min and body temperature 36.7°C. His mental status was alert but dysarthric feature and left side hemiparesis was shown. Oral examination by a dentist revealed gingivitis, dental decay, very poor hygienic state and moderate amount of plaque and calculus. On chest examination, abnormal breathing sounds, such as crackle and expiratory wheezing, were not audible. There were no other physical abnormalities noted.

Laboratory examination showed the hemoglobin was 13.8 g/dL, hematocrit 40.4%, white blood cell 6,700/μL, platelet 177,000/μL. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 14 mm/h. C-reactive protein was 0.5 mg/dL. Cytologic examination of sputum was negative. Bacteriologic examination of sputum showed no evidence of mycobacterial tuberculosis or fungal infection. Chest radiographs revealed increased opacity and atelectatic change in the anterior segment of the left upper lobe, suggestive of obstructive pneumonitis or pulmonary tuberculosis (Figure 1A). A computed tomographic scan (CT) of the thorax showed consolidation and air bronchogram in the left upper lobe with partial atelectasis, but significant enlargement of mediastinal or hilar lymph node was not observed (Figure 1B). Bronchoscopic examination showed a pink and soft protruding mass obstructing the left upper lobar bronchus was suggestive of bronchogenic carcinoma (Figure 2A). The presumptive diagnosis by bronchoscopy was bronchogenic carcinoma. However, biopsy of the lung tissue obtained by bronchoscopy showed gram-positive sulfur granules and hyphe-like components within a granulomatous formation, which showed squamous metaplasia of bronchial mucosa with mixed inflammatory cellular infiltration and some colonies of actinomycosis (Figure 3). The final diagnosis was endobronchial actinomycosis.

Figure 1A.

A 69-year-old man with pulmonary actinomycosis induced by fish bone. Chest radiograph shows ill-defined increased opacity and atelectatic change (arrow) in the left upper lung zone.

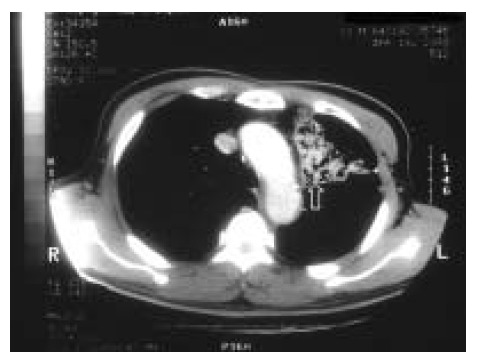

Figure 1B.

A chest CT scan obtained at the level of the aortic arch reveals consolidation with airbronchogram (arrow) in the left upper lobe. Fish bone was not identified in the CT scan.

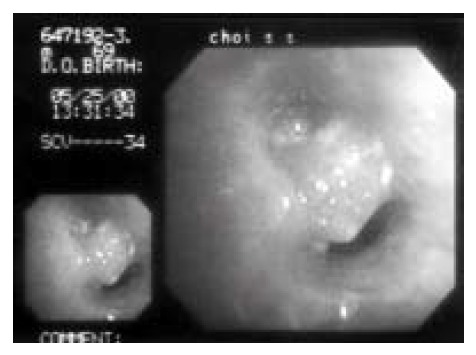

Figure 2A.

This fiberoptic bronchoscopic finding show a soft tissue mass in the left upper lobar bronchus

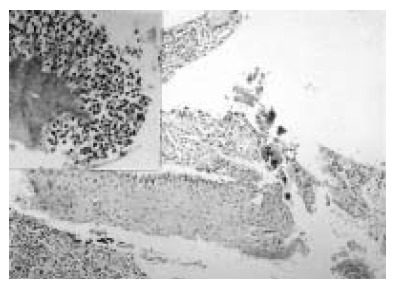

Figure 3.

Photomicroscopic findings show squamous metaplasia of bronchial mucosa with mixed inflammatory cellular infiltration and some colonies of actinomycosis (H&E, ×100). Inset shows a colony of filamentous actinomycotic organism surrounded by many neutrophils (H&E, ×200).

The patient was given 10 million units of intravenous penicillin-G daily for two weeks. The opacities and infiltration on chest radiographs gradually decreased. After two weeks of penicillin therapy, he was switched to 2 g amoxicillin daily. At discharge, more than 80% of his pulmonary infiltration had resolved and the remainder was markedly reduced in size. After discharge, oral antibiotics were administered for 4 weeks. Follow-up bronchoscopic examination revealed a complete resolution of the endobronchial mass lesion and, in place, a foreign body was exposed (Figure 2B). The removed foreign body was proven to be a very small-sized fish bone. This unfortunate accident is the first case of a foreign body-induced pulmonary actinomycosis in Korea. The patient was completely cured with no remaining symptoms.

Figure 2B.

The follow-up bronchoscopic finding shows a foreign body at the previous lesion, which was proven later to be a small fish bone.

DISCUSSION

Actinomycosis is an indolent, slowly progressive infectious disease caused by anaerobic or microaerophilic bacteria that normally colonize the mouth, colon and vagina. Gram- positive bacteria make up 26.1% of the isolates in patients with chronic gingivitis and include primary Actinomyces naeslundii, A israelii and A viscosus6). Jon B. Suzuki et al. present that seeding of tooth-associated materials containing Actinomyces species into the pulmonary field may have resulted in pulmonary actinomycosis7). Actinomyces israelii, Actinomyces naeslundii, Actinomyces odontolyicus, Actinomyces viscosus, Actinomyces meyeri and Propionibacterium propionicum are established but less common causes of disease8,9).

Classic features include extension to contiguous structures by crossing natural anatomic boundaries and the formation of fistulas and sinus tracts. Because this infection is commonly confused with a neoplasm, it has been called “the most misdiagnosed disease10). Thoracic actinomycosis presumably is caused by aspiration of contaminated material from mouth or oropharynx11,12). Actinomycotic pulmonary infection may follow a characteristic course demonstrating locally invasive disease or, more often, may be manifested by an entirely nonspecific pneumonitis, cough, anorexia, chest pain and weight loss. The thoracic form accounts for about 20% of the cases. The cervicofacial and abdominal forms account for about 50% and 30%, respectively13,14). Endobronchial disease due to this pathogen rarely is reported15), Ilana Ariel et al. reported five case of actinomycosis of the main bronchi or trachea which were suggestive clinically of bronchogenic carcinoma. Ariklapholz et al.16) reported one case of endobronchial actinomycosis in an AIDS patient. In 1957, Bates and Cruickshank reported 85 cases of pulmonary actinomycosis. Of these, 7 patients had undergone resectional therapy and in all these the preoperative diagnosis was carcinoma of the lung17). The first report of foreign body-induced pulmonary actinomycosis was the Spanish patient case in 1991, which was aspirated chicken bone foreign body18). Foreign body associated with endobronchial actinomycosis in our case was attributed to aspirated fish body. Because of his poor oral hygiene and swallowing difficulty, there may have been unsuspected aspiration of oropharyngeal secretion of the foreign body which subsequently led to endobronchial disease.

The diagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosis is usually based on microscopic examination or culture of the material aspirated from the lesion, anaerobic sputum culture, or histologic examination of the resected specimen and from bronchoscopic biopsy. The hallmark of actinomycosis is the formation of the yellow sulfur granules. The microorganism are slender branching bacilli embedded in the matrix of the granules. Sulfur granules are, in many cases, very hard to find and in 26 percent in Brown’s series the diagnosis was based on the finding of only a single sulfur granule in a lesion. The chance of finding it in a small biopsy is, of course, much smaller and the necessity for serial sections cannot be overemphasized. CT scan of pulmonary actinomycosis usually reveals a soft tissue mass with varying degree of infiltration, abscess formation and pleural thickening adjacent to the airspace consolidation19,20). The bronchoscope findings are usually not diagnostic and include yellowish, hard or friable endobronchial mass21).

Therapeutic measures usually consist of several weeks of high dose intravenous penicillin, tetracycline, clindamycin or erythromycin. Abscess and empyema require surgical drainage in addition to antibiotic therapy. The prognosis is usually favorable with early detection and proper management.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smego RA, Foglia G. Actinomycosis. Clin infect Dis. 1998;26:1255–63. doi: 10.1086/516337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassiri AG, Girgis RE, Theodore J. Actinomyces odontolyticus thoracopulmonary infection. Two cases in lung and heart-lung transplant recipients and a review of the literature. Chest. 1996;109:1109–11. doi: 10.1378/chest.109.4.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinnear WJM, MacFarlane JT. A survey of thoracic actinomycosis. Respir Med. 1990;84:57–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(08)80095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russo Thomas A. Agents of actinomycosis. Principles and Practice of infectious disease. 2000:2645–2652. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mingrone H, Perrone R, La Rosa S. Primary bronchial actinomycosis and foreign body. Medicina (B Aires) 1995;55:337–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jon B, Suzuki, Allan L. Pulmonary actinomycosis of periodontal origin. J periodontal. 1984;55:581–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.10.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen HA, Scatarige JC, Kim MH. Actinomycosis : CT finding in six patients. AFR. 1987;149:1235–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.149.6.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris JF, Kilbourn P. Systemic actinomycosis caused by actinomyces odontolyticus. Ann Intern Med. 1974;81:700. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-81-5-700_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slots J, Moendo D, Langebaek J, frandsen A. Microbiota of gingivitis in man. Scand J Dent Res. 1978;86:174. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1978.tb01929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slade PR, Slesser BV, Southgate J. Thoracic actinomycosis. Thorax. 1973:28–85. doi: 10.1136/thx.28.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JR. Human actinomycosis : A study of 181 subjects. Human Pathol. 1973;4:319–30. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(73)80097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bates M, Cruickshank G. Thoracic actinomycosis. Thorax. 1957;12:9–124. doi: 10.1136/thx.12.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorman JP, Aron KV. Pulmonary pseudotumor caused by actinomycosis. Tes Med. 1976;72:65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miracco C, Marino M, Lio R, Cornetti M, Luzi P. Primary endobronchial actinomycosis. Eur Respir J. 1988:670–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ilana Ariel, Raphael Breuer, Nidal S, Kamal Endobronchial actinomycosis simulating bronchogenic carcinoma : Diagnosis by bronchial biopsy. CHEST. 1991:493–95. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.2.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ignacio Cendan Ariklapholz. A case of Endobronchial disease in a patient with AIDS. CHEST. 1993;103:1886–87. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harvey JC, Cantrel JR, Fisher AM. Actinomycosis : its recognition and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1957;46:868–885. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-46-5-868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Julia G, Rodriguez de Castro F. Endobronchial actinomycosis associated with a foreign body. Respiration. 1991;58:229–30. doi: 10.1159/000195934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau KY. Endobronchial actinomycosis mimicking pulmonary neoplasm. Thorax. 1992;47:664–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.8.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalhoff K, Wallner S, Finck C, Gatermann S, Wieman KJ. Endobronchial actinomycosis. Eur Respir. 1994;7:1189–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinnear WJM, MacFarlane JT. A survey of thoracic actinomycosis. Respir Med. 1990;84:57–9. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(08)80095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]