Abstract

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is very rare and no primary myxoid leiomyosarcoma in the liver has been reported yet. Most cystic space-occupying lesions in the liver are benign in nature. But, rarely, malignancy could appear as a cystic lesion by ultrasonographic examination. A 64-year-old woman with a huge cystic mass detected by hepatic ultrasonography was diagnosed as primary hepatic myxoid leiomyosarcoma by immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies after various image studies and fine needle aspiration biopsy of the liver mass.

Keywords: Leiomyosarcoma, Liver neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

More than 25 cases of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma have been reported from many countries since the first publication in Japan in 19951–4). Myxoid leiomyosarcoma is a distinctive and rare tumor found in many organs, such as the digestive tracts, uterus, ovary and prostate5–7), but has not previously been reported in the liver.

In Korea, primary malignant hepatic neoplasm is the third leading cause of death8) and the most common hepatic neoplasm is hepatocellular carcinoma related to chronic hepatitis B9). Another common space-occupying lesion in the liver is the benign cyst10). Therefore, differential diagnosis of hepatic masses is very important.

We report a case of primary hepatic myxoid leiomyosarcoma which was treated successfully by extended right lobectomy and appears to be the first case in English literature.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old Korean woman visited the out-patient clinic of the Department of Internal Medicine of Yeungnam University Medical Center complaining of a palpable mass with dull pain on the right upper quadrant for 10 days. She was referred from a local clinic with the report of a huge cystic mass detected by ultrasonography. The pain was not like biliary colic in nature and she had no other symptom. The patient was a housewife, non-alcohol drinker and non-smoker. She had never been abroad. She had a medical history of a subtotal gastrectomy with gastrojejunostomy 7 years earlier for the treatment of benign gastric ulcer bleeding.

The palpable portion of the liver was non-tender and no bruit was heard over it. Splenomegaly, spider angioma, superficial venous collaterals and jaundice were not detected.

Liver function test results were abnormal; AST 48 IU/L (normal 13–35 IU/L), ALT 26 IU/L (normal 9–40 IU/L), ALP 242 IU/L (normal 26–88 IU/L), γ-GTP 165 IU/L (normal 8–64 IU/L), and LDH 620 IU/L (normal 150–550 IU/L). Tests for hepatitis B and hepatitis C were all negative, and serum α-fetoprotein was within the normal limit. All other laboratory findings were normal.

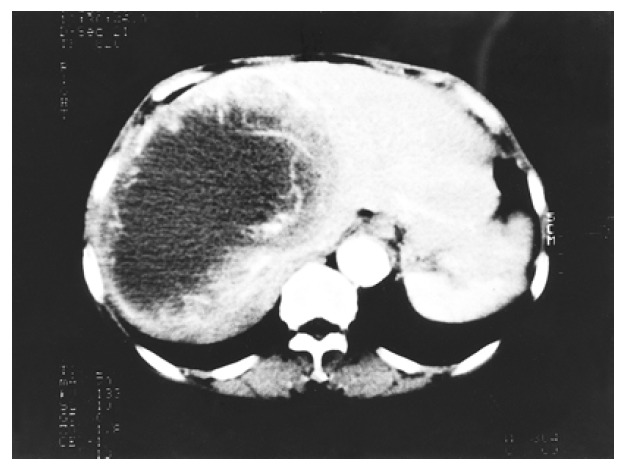

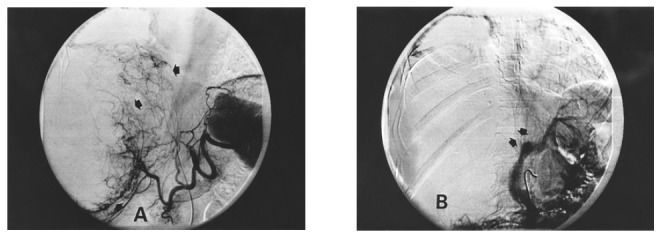

Chest radiography was normal, but a large soft-tissue mass was apparent in the right upper quadrant on a plain abdominal film. Ultrasonography of the hepatobiliary system showed a mixed cystic lesion measuring 14.5 cm in diameter and occupying almost all of the right lobe of the liver. Contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomographic (CT) scan showed a thick-walled cystic mass of 15 cm in diameter in the right hepatic lobe with serpentine enhancement in the wall during the early arterial contrast phase (Figure 1). Pelvic CT showed normal uterus and adnexa. Angiography showed a hypervascular tumor which displaced hepatic artery branches in segments 5, 6, 7 and 8, and neovascularization was noted at the area of segments 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 (Figure 2). Technetium99m phytate liver scan showed hepatomegaly with a huge space-occupying lesion in the right lobe. Neither splenic nor bone marrow uptake was increased. Technetium99m RBC scan revealed no evidence of hepatic hemangioma.

Figure 1.

Intravenous bolus computed tomography of the abdomen showed a huge cystic mass with thick wall, occupying the most of the right lobe of the liver. The tumor wall has serpentine vascular enhancement during early contrast phase.

Figure 2.

(A) Celiac angiography revealed a huge hypervascular mass in the right lobe of the liver. Tumor neovascularization was noted at the area of segments 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8. (B) Portovenography revealed total right portal vein defect.

Ultrasonography of the thyroid revealed a 1.5×2.5×3.5 cm tumor in the right lobe, isodense with the gland parenchyma and having a 1.5 cm cystic lesion in the center. Color Doppler showed hyperdynamic blood flow around the lesion. Technetium99m pertechnetate thyroid scan showed a cold lesion in the right lobe. Small bowel series, barium enema and gastrofiberoscopy showed nothing unexpected.

Diagnostic needle aspiration of the liver mass produced clear amber-colored fluid with 50 white blood cells /HPF, all of which were lymphocytes; 30–40 red blood cells /HPF; LDH 2135 IU/L and no visible malignant cell. Other biochemical findings of the fluid were nonspecific. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy and cytology of the thyroid mass showed follicular proliferation and cystic degeneration.

After laparotomy, a right hepatic lobectomy, wedge resection of the left lobe and cholecystectomy were done. The perihepatic, perigastric and omental veins were engorged, and hepatomegaly without cirrhotic change was noted. A huge mass bulged out from the right hepatic lobe and another mass, several centimeters in size, was found on segment 4. The portal veins and their branches appeared intact. No tumor was found on other organs. The patient was discharged well on the seventeenth postoperative day and remains free of recurrent hepatic tumor or other evidence of neoplasm 24 months after surgery.

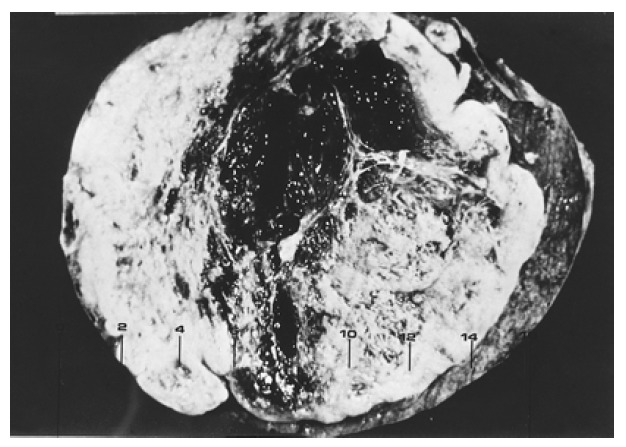

The resected specimen consisted of a whole right lobe of liver and a wedge-shaped portion of the left lobe. The external surface showed protruding bulging mass. On sectioning, a well-demarcated, grayish-white, multiloculated subcapsular tumor measuring 7.5×16.0×4.5 cm and having central cystic degeneration was noted. The surrounding solid portion was composed of soft, homogenous tissue with multifocal cystic and mucinous degeneration. The tumor showed an expanding growth pattern and the capsule was replaced by the expanding tumor mass. Several daughter nodules were noted (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Gross examination of the excised tumor: Relatively well-demarcated, grayish-white mass measuring 7.5×16.0×4.5 cm in size showed expanding growth pattern. The tumor contained central cystic degeneration and homogeneous and homogenous solid portion.

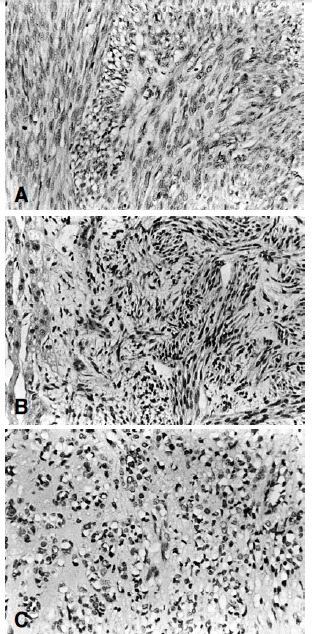

Microscopic findings revealed anaplastic spindle cell proliferation with a diffuse myxochondroid background. The tumor cells had spindle-shaped, hyperchromatic, occasionally pleomorphic nuclei with frequent mitotic figures (5–9/HPF). Mild cellular pleomorphism with atypia was noted. Most areas consisted of tumor cells which had typical cigar-shaped nuclei with a prominent nucleolus and fibrillary cytoplasm arranged in interlacing bundles and short fascicles (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Light microscopic examination : (A) Sections of the liver mass showed interlacing fascicles of spindle-shaped nuclei and perinuclear vacuoles (H&E, ×200) (B) Tumor showed interlacing spindle-shaped cells arranged in fascicles, with hepatocyte present in the left side. (H&E, ×200) (C) Tumor cells showed round nuclei with perinuclear vacuoles. The stroma revealed myxoid change. (H&E, ×200)

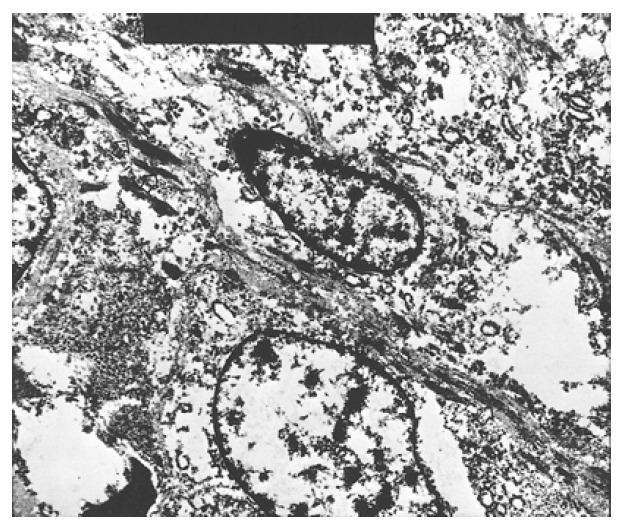

Occasionally, individual and/or aggregated primitive round tumor cells with vacuolated cytoplasm were scattered in the loose chondroid matrix (Figure 4). Small to medium- sized blood vessels were proliferated, showing a focal hemangiopericytic pattern. Immunohistochemical stains for vimentin, desmin, lysozyme and α1-antitrypsin were all positive, and keratin, actin and factor VIII were all negative (Figure 5). Electronmicroscopic examination showed a well-developed basal lamina, plasma-membrane dense body, pinocytic vesicles and scattered dense filaments. These findings confirmed the myofilamentous nature of the tumor (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical stains of the resected mass showed positive staining for smooth muscle actin. (Immunohistochemical stain, ×200)

Figure 6.

Electromicroscopic examination showed myofilaments (arrow) with dense bodies. (EM, ×6000)

DISCUSSION

Primary hepatic mesenchymal tumors are rare. Sarcomas occupy only 1% to 2% of all primary malignant tumors of the liver1, 2) and most of the primary hepatic malignant tumors are either hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma. Nearly all primary sarcomas of the liver are angiosarcomas, epitheloid hemangioendotheliomas, undifferentiated embryonal sarcomas or leiomyosarcomas, with more than 70% being angiosarcoma or undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma2).

Leiomyosarcomas are malignant neoplasms that arise from the smooth muscle. Focal or diffuse myxoid changes may occur in many types of benign and malignant soft tissue neoplasms. The myxoid variant of leiomyosarcomas is distinctive and rare, with only 43 cases having been reported up to 19935–7). The frequent locations of the disease were the uterus (the most common; 28 cases), ovary (3 cases) and extragenital area (12 cases); i.e., digestive tract, retropertoneum, maxillary antrum, parotid gland and prostate5–7).

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is a very rare tumor occuring predominantly in elderly or middle-aged individuals14), with fewer than 25 cases reported in the literature to date11, 12) and, to our knowledge, no primary myxoid leiomyosarcoma in the liver has been reported. Intrahepatic leiomyosarcoma may be derived from the smooth muscle cells of the bile ducts or blood vessels. No definite underlying etiologic factors are known, and the tumor is not associated with cirrhosis, although thorotrast associated lesions and an AIDS-related case in a young girl have been reported11, 13).

Usually, primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is a large, solitary, no encapsulated mass. Massive tumor at the time of diagnosis has a size range of 6 to 35 cm and the typical weight is 1 to 5 kg. The largest tumor reported was 11,270 g. The right lobe is the usual site14). A large graysh white solitary mass with hemorrhage and necrosis is typical and a few satellite nodules may be noted. The Microscopic features of leiomyosarcoma are uniform spindle shaped or epithelioid smooth muscle cells with lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, which display longitudinal striation. Nuclei are elongated or oval and exhibit hyperchromatism and pleomorphism with numerous mitoses: from one per 2 or 3 HPF to 17 per 10 HPF1, 15). Tumor cells are disposed in intersecting bundles. Positive cells on immunohistochemical stains for vimentin and desmin are negative for cytokeratin16–18). In the myxoid variant, amorphous intercellular material that are positive on Alcian blue stain at pH 2.5 and colloidal iron staining may represent stromal acid mucopolysaccharides3, 6). The myofilamentous nature of primary hepatic leiomyosarcomas can be confirmed by the ultrastructural features of well-developed basal lamina, plasma membrane dense bodies, micropinocytic vesicles, and dense filaments1, 19).

To confirm the primary nature of leiomyosarcoma, it is necessary to exclude metastasis from extrahepatic site which is more common20). Extrahepatic origin was not entirely excluded in the previous publications of liver leiomyosarcoma. But no extrahepatic tumor was identified in current case by abdominal and pelvic CT, small bowel contrast study, or laparotomy. In myxoid leiomyosarcoma, the sparse cellular density secondary to an abundant amount of extracellular substance makes a conventional mitotic count difficult and mitotic count is less useful as a marker of malignancy7).

Indeed, uterine myxoid leiomyosarcomas showing abnormally low mitotic counts have a great potential for aggression5). For this reason, it has been suggested that mitotic count should be taken separately in the solid and myxoid areas6) as, in the former, the counts are definitely higher. In the present case, the mitotic index in the solid area averaged 7 per 10 HPF, and the neoplasm was considered to be malignant according to the criterion of the mitotic index.

Space-occupying lesion (SOL) of the liver was detected in 1.24% of the general Korean population by screening ultrasonographic examination and 67.1% of SOLs were cystic lesions21). Cystic hepatic masses should be evaluated thoroughly to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate management for malignant tumors. Surgical resection is the most effective method of treatment but is usually not possible because of massive tumor. The majority of patients have recurrent massive hepatic tumor but the current case was well managed by effective surgical treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maki HS, Hubert BC, Sajjad SM, Kirchner JP, Kuehner ME. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Arch Surg. 1987;122:1193–1196. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1987.01400220103020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE. Bokus Gastroenterology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1987. pp. 2488–2500. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watnuki K, Kusama K. [A case of leiomyosarcoma of the liver] Nippon Ika Daigadu Zasshi. 1955;22:552. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsuji M, Takenaka R, Kashihara T, Hadama T, Tere Wata N, Mori N. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis. Pathol Int. 2000;50(1):41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King ME, Dickersin GR, Schully RE. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the uterus. A report of 6 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982;6:589–598. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salm R, Evans DJ. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma. Histopathology. 1985;9:159–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1985.tb02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francisco FN, Alberto A, Isabel RA, Juan JS. Myxoid leiomyosarcoma of the ovary: analysis of three cases. Hum Pathol. 1991;22:1268–1273. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90110-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilsoon K. Mortality patterns of major causes of death in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 1995;38:132–145. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyoseok L, Jikon R, Sookhyang J, Chungyang K. A prospective study on the incidence and the risk factors of the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1993;25:116–122. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Changsik S, Ukyun N, Sangkweon O, Sungwon C, Chansup S. Diagnosis of simple hepatic cysts using ultrasonography. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1986;18:519–524. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross JS, Del Rosario A, Bui HX, Sonbati H, Solis O. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a child with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90014-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paraskevopoulos JA, Stephenson TJ. Case report. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver. HPB Surg. 1991;4:157–163. doi: 10.1155/1991/64252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shurbaji MS, Olson JL, Kuhajda FP. Thorotrast-associated hepatic leiomyosarcoma and cholangiocarcinoma in a single patient. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:524–526. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fong JA, Ruebner BH. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver. Hum Pathol. 1974;5:115–119. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(74)80105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McIntyre N, Benthamou JP, Bircher J, Rizzetto M. Oxford Text Book of Clinical Hepatology. Vol. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. pp. 1072–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakizoe S, Kojiro M, Nakashima T. Hepatocellular carcinoma with sarcomatous change : Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical studies of 14 autopsy cases. Cancer. 1987;59:310–316. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870115)59:2<310::aid-cncr2820590224>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DE, Herndier BG, Medeiros LJ, Warnke RA, Rouse RV. The diagnostic utility of keratin profiles of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:187–197. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198803000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haratake J, Horie A. An immunohistochemical study of sarcomatoid liver carcinomas. Cancer. 1991;68:93–97. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910701)68:1<93::aid-cncr2820680119>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloustein PA. Hepatic leiomyosarcoma: Ultrastructural study and review of differential diagnosis. Hum Pathol. 1978;9:713–715. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(78)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkins FP, Jordan GL, McGavran MH. Primary leiomyoma of the liver: successful treatment by lobectomy and presentation of criteria for diagnosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim KY, Lee HJ, Suh JI, Back CW, Lee DJ, Song YD, Doh GS, Jeon KJ, Kim JH. A clinical study of liver space-occupying lesion among the visitors in an automated med-screening center by ultrasonographic examination. Kor J Med. 1996;51:178–186. [Google Scholar]