Abstract

Liver infarction and acrodermatitis enteropathica are rare complications of chronic pancreatitis. This report shows the case of a 56-year-old man who developed liver infarction due to portal vein thrombosis from chronic pancreatitis and acrodermatitis enteropathica during the course of his treatment. The rare combination of these complications in a patient with chronic pancreatitis has never previously been reported in the literature.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, Alcoholic; Infarction, Liver; Acrodermatitis

INTRODUCTION

Liver infarction with portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is a very rare complication of pancreatic inflammatory disease because of peculiarities in its vascular architecture, such as its intrahepatic double blood supply system1, 2). Acrodermatitis enteropathica is also an unusual disorder characterized by alopecia, oral and periorificial dermatitis and gastrointestinal disturbance which and caused by zinc deficiency3, 4). Recently, we experienced a patient with chronic pancreatitis who had a liver infarction with PVT and presented an acrodermatitis enteropathica during the course of his treatment with total parenteral nutrition (TPN), as herein reported.

CASE

A 56-year-old man, who had been a heavy drinker, presented symptoms of general weakness, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea and weight loss and was admitted to the hospital. On examination, he was found to be cachectic and his abdomen slightly distended with shifting dullness. Laboratory examination revealed a hemoglobin level of 13.1 g/dL; white blood cell count, 17,800/mm3; platelet count, 553,000/mm3; albumin, 2.6 g/dL; total bilirubin, 0.3 mg/dL; GOT, 48 IU/L; GPT, 22 IU/L; and alkaline phosphatase, 117 IU/L. His serum amylase was 856 IU/L and serum lipase 1,077 IU/L. A computed tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen (Figure 1) revealed evidence of acute exacerbated, chronic pancreatitis, including pseudocysts, one of which was approximately 7 cm in diameter and was located in the tail of the pancreas with adjacent splenic vein occlusion. In addition, right portal vein occlusion, with corresponding perfusion defect and liver infarction, was noted. The patient was treated initially with intravenous fluids, antibiotics and TPN. Two weeks after treatment including TPN, the patient exhibited multiple skin lesions and continued to experience diarrhea more than 10 times daily. These skin lesions were vesiculopustular and erythematous eruptions with scales on the face (Figure 2A) and perineal areas. During the following week, the lesions spread to involve the hands and feet (Figure 2B, 2C). He became depressed and agitated. In view of typical skin lesions, mental change and protracted diarrhea, we strongly suspected acrodermatitis enteropathica due to zinc deficiency. His serum zinc level was found to have fallen to 17.4 μg/dL (normal range, 70 to 150 μg/dL) and, therefore, we initiated therapy with zinc sulfate at 5 mg daily. Three to four days of zinc supplementation produced marked improvement of the diarrhea and, after one week of zinc supplementation, the skin lesions began to alleviate. The patient continued to do well until five weeks after TPN when abdominal pain and fever developed. With strong suspicions of an infected pancreatic pseudocyst, we performed an abdominal CT scan and subsequently a percutaneous pigtail insertion to drain the pseudocyst. Soon thereafter, he felt well with no pain or fever. A repeat CT scan 10 days later showed total collapse of the pseudocyst and resolution of the PVT and liver infarction. On the 74th hospital day, he was discharged without any problem. By this time, his skin lesions had almost healed.

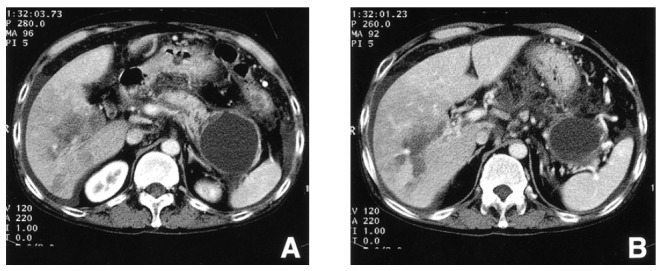

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen demonstrates irregular dilatation of the pancreatic duct, diffuse peripancreatic inflammation and a large pseudocyst in the tail of the pancreas with adjacent splenic vein occlusion (A). Portal vein occlusion is shown at the level of the second order branches of the right portal vein with its corresponding perfusion defect and centering geographic low attenuation, suggesting infarction (B).

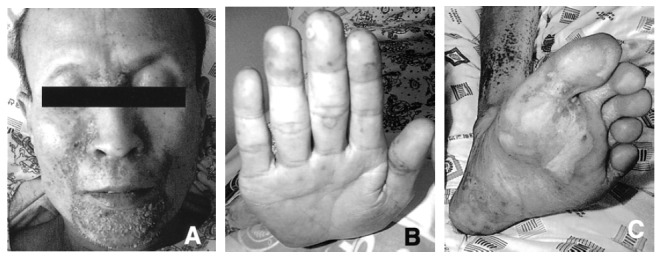

Figure 2.

Multiple oozing crusted erythematous patches are found on the forehead, nasolabial and perioral areas (A). Vesiculopustular and erythematous eruptions are also seen on the palm (B) sole (C).

DISCUSSION

PVT is a well-recognized phenomenon and can occur as a complication of many diseases. Important risk factors for PVT are cirrhosis, hepatobiliary malignancies, pancreatitis and hematological disorders5). The pathogenesis of portal vein occlusion in pancreatic disease may be the result of several factors1, 6–8) First, the pancreas is anatomically closely associated with the portal vein, the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein. Thus, pancreatic disease, including acute inflammation or pseudocyst, can damage these vessels and cause venous thrombosis. Second, splenic vein thrombosis may precede and then extend to involve the portal vein. Third, a pseudocyst may compress the portal vein. Infarction in the human liver is generally considered to be exceedingly low in incidence compared with other organs9). This can be attributed to the peculiarities of its vascular architecture, such as the intrahepatic double blood supply system and the high oxygen delivery of the portal vein. However, liver infarction may be occurred only when the hepatic artery or portal vein are occluded, and also caused by systemic circulatory insufficiencies1, 2, 9). Up to now, reports of liver infarction with PVT are few1, 9). Recently, we experienced a case of chronic pancreatitis with PVT and liver infarction. It appeared that the PVT might have been caused by either extension of the splenic vein thrombosis or by erosion of the portal vein due to a pseudocyst.

Another problem in our case was zinc deficiency. Zinc is a well-known trace element essential for the normal growth and development of animals and appears to be important in wound healing and cell-mediated immunity4, 10). As in the present case, patients with alcoholic chronic pancreatitis appear to be a high-risk group for the development of severe zinc deficiency, contributed to by diminished dietary intake, enhanced urinary excretion of zinc and, probably, markedly diminished zinc absorption. Several other studies on chronic pancreatitis have also found disturbance of the zinc metabolism and a low plasma zinc concentration11–15). This deficiency was said to be mainly due to fat malabsorption. Our patient appears to have been suffering zinc deficiency, or at least a marginal zinc status, before admission. In this situation, TPN rapidly worsened his zinc deficient state, thereby causing these clinical manifestations.

To our knowledge, no reports of the rare combination of these complications, i.e., liver infarction and acrodermatitis enteropathica, in a patient with chronic pancreatitis have been published. By the time the patient was discharged, the liver infarction, pseudocysts and skin lesions were completely resolved. However, his zinc level remained in the subnormal range. This was thought to have been caused by the chronic pancreatitis and his un-recovered nutritional state.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yamashita K, Tsukuda H, Mizukami Y, Ito J, Ikuta S, Kondo Y, Kinoshita H, Fujisawa Y, Imai K. Hepatic infarction with portal thrombosis. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:684–688. doi: 10.1007/BF02934122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saegusa M, Takano Y, Okudaira M. Human hepatic infarction: histopathological and postmortem angiological studies. Liver. 1993;13:239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1993.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehgal VN, Jain S. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Clin Dermatol. 2000;18:745–748. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(00)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasman-Jones C. Zinc deficiency states. Adv Intern Med. 1980;26:97–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen HL. Changing perspectives in portal vein thrombosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;232(Supp):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoshi S, Tanimura S, Mitsui K. An inflammatory pancreatic mass complicated by portal vein thrombosis: a case report and review of the Japanese literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCormick PA, Chronos N, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N, McLaughlin JE. Pancreatic pseudocyst causing portal vein thrombosis and pancreatico-pleural fistula. Gut. 1990;31:561–563. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.5.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warshaw AL, Jin GL, Ottinger LW. Recognition and clinical implications of mesenteric and portal vein obstruction in chronic pancreatitis. Arch Surg. 1987;122:410–415. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1987.01400160036003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen V, Hamilton J, Qizilbash A. Hepaticinfarction. A clinicopathologic study of seven cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen Jl, Kay NE, McClain CJ. Severe zinc deficiency in humans: association with a reversible T-lymphocyte dysfunction. Ann Intern Med. 1981;95:154–157. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-95-2-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quilliot D, Dousset B, Guerci B, Dubois F, Drouin P, Ziegler O. Evidence that diabetes mellitus favors impaired metabolism of zinc, copper and selenium in chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2001;22:299–306. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gjorup I, Petronijevic L, Rubinstein E, Andersen B, Worning H, Burcharth F. Pancreatic secretion of zinc and copper in normal subjects and in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Digestion. 1991;49:161–166. doi: 10.1159/000200716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tulikoura I, Vuori E. Effect of total parenteral nutrition on the zinc, copper and manganese status of patients with catabolic disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986;21:421–427. doi: 10.3109/00365528609015157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams RB, Russel RM, Dutta SK, Giovetti AC. Alcoholic pancreatitis: patients at high risk of acute zinc deficiency. Am J Med. 1979;66:889–893. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(79)91148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weismann K, Wadskov S, Mikkelsen HI, Knudsen L, Christensen KC, Storgaard L. Acquired zinc deficiency dermatosis in man. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1509–1511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]