Abstract

Background:

Forced oscillation technique (FOT) is a method to characterize the mechanical properties of the respiratory system over a wide range of frequencies. Its’ most important advantage is to require minimal cooperation from the subject. This study was performed to evaluate the usefulness of the FOT applications in patients with bronchial asthma by estimating the associations between asthma severity and FOT parameters, and the relationships between FOT and spirometry parameters.

Methods:

216 patients with asthma were enrolled in this study. Patients were classified into 3 different groups according to their symptoms and pulmonary functions. Respiratory impedance, resistance (at 5 Hz, 20 Hz, 35 Hz) and resonant frequency were measured by FOT. FEV1, FVC and MMEF were measured with conventional spirometry.

Results:

There were significant differences of resonant frequency, resistance at 5 Hz and 20 Hz, resistance difference at 5 Hz and 20 Hz according to asthma severity (p<0.05, respectively). Resonant frequency, resistance at 5 Hz, and impedance were significantly correlated with FEV1 (r = −0.55, −0.48, −0.49, p<0.05, respectively), and with MMEF in patients with normal pulmonary function (r = −0.37, −0.35, −0.34, p<0.05, respectively). Resistance at 5 Hz had similar reproducibility compared to FEV1 (resistance at 5 Hz, r = 0.78 vs FEV1, r = 0.79).

Conclusion:

FOT is a useful and alternative method to evaluate the clinical status of bronchial asthma. Further studies will be needed to clarify its value for a wide range of clinical applications.

Keywords: Asthma, Forced oscillation

INTRODUCTION

Spirometry is the standard method to measure the airway obstruction in chronic lung diseases1, 2). In some situations, however, spirometric measurement of lung function is difficult largely because of inability to perform adequate forced expiration or lack of patient’s cooperation. Whole body plethysmography is a more advanced method, but it also needs the patient’s cooperation and requires expensive devices3).

In 1956, DuBois et al.4) first described an oscillatory method for measurement of the respiratory system mechanics, but this technique was not accepted widely because of its technical difficulties and the greater attractiveness of the body plethysmography. Recent advances in microprocessor technology, however, have solved many earlier problems, and Forced oscillation Techniques (FOT) becomes more widely used in clinical pulmonary laboratories5).

FOT, which characterize the mechanical properties of the respiratory system over a wide range of frequencies, is a non-invasive and effort-independent method for measuring airway resistance. The primary measurements of FOT are the pressure and flow generated at a given frequency, and the instantaneous pressure-flow relationship, namely impedance of the respiratory system (Zrs), is further analyzed into a real part or resistance (Rrs) and an imaginary part or reactance (Xrs)5, 6).

An important advantage and the clinical potential of FOT is that it is rapid and demands only the patient’s passive cooperation. Hence, FOT is proved to be feasible for lung function measurement in infants7) and young children8, 9), for challenge tests10), for reversibility tests of airflow obstruction, and for large epidemiologic surveys5).

Treatment of bronchial asthma is based on its severity which is determined by symptoms, spirometric measurement of forced expiratory volume at 1 second (FEV1) and diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow (PEF)11). Some patients with asthma may describe obscure symptoms and inadequately perform spirometry, so proper estimation of asthma severity is often impossible. The FOT is known to be more sensitive to lower airway obstruction, such as bronchial asthma, than to interstitial lung disease and chest wall pathology5).

This study was performed to evaluate the usefulness for the clinical applications of FOT in patients with bronchial asthma by estimating the associations between asthma severity and FOT parameters, and the relationships between FOT and spirometry parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

Of the patients who visited our allergy clinics for the evaluation of respiratory complaints from July 1997 to June 1999, 216 patients with bronchial asthma were enrolled in this study. Asthma was clinically diagnosed on the basis of typical respiratory symptoms, such as dyspnea, wheezing, coughing or presence of nocturnal aggravation plus one of the following Two; 1) reversible airflow limitations-improvement of FEV1 of more than 12% after inhalation of 200 μg of salbutamol MDI or long-term anti-inflammatory treatment, or 2) significant nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness-methacholine PC20 less than 25 mg/mL. Among 216 patients, male:female ratio was 102:114, mean age was 46.3±13.8 years (age range 19 to 70 years), and 77 patients had concurrent rhinitis.

Baseline data, including age, sex, height and asthma symptoms were obtained from each patient at the time of procedures. Then, patients were classified into mild asthma (mild group, n=111, 51.3%), moderate persistent asthma (moderate group, n=78, 36.1%) and severe persistent asthma (severe group, n=27, 12.6%) according to NHLBI guideline11) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| Asthma severity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n=111) | Moderate (n=78) | Severe (n=27) | |

| M/F | 61/50 | 32/46 | 9/18 |

| Age (yr) | 44.1±13.8 | 47.5±14.3 | 50.7±14.8 |

| Height (cm) | 164.8±8.2 | 161.5±7.6 | 160.2±8.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 63.9±9.1 | 62.5±10.5 | 59.8±9.4 |

| Sputum eosinophil (%) | 32.8±33.7 | 37.8±35.6 | 23.8±28.9 |

| Total IgE (U/mL) | 588.8±11.2 | 741.5±8.3 | 501.0±10.0 |

| M-PC20 (mg/mL)* | 4.3±5.8 | 2.0±4.4 | 1.2±5.1 |

| PEFR (pred %)* | 88.7±11.9 | 80.1±12.1 | 61.9±17.1 |

| FEV1 (pred %)* | 98.1±16.3 | 83.2±15.3 | 57.6±20.0 |

| FEV1/VC (pred %)* | 76.1±10.8 | 68.8±12.2 | 59.9±13.9 |

| MMEF (pred %)* | 65.9±24.4 | 47.9±28.1 | 26.6±16.6 |

p<0.05: between each group.

Total IgE, M-PC20: geometric mean.

2. Forced Oscillation Techniques and Spirometry

FOT measurements were performed with a pneumotachograph and its built-in pressure transducer using commercially available equipment, MS-IOS Digital Instrument (Master Screen IOS version 4.32, Jaeger, Würzburg, Germany). The patient was seated comfortably with the neck slightly extended. Measurements were carried out during quiet breathing through a mouthpiece, and the cheeks were supported by the patient’s palm and finger and the nose was occluded with nose clips to minimize the upper airway artifact. After adaptation to this procedure, FOT were processed for 30 second tidal breathing. The digitized pressure and flow signals were sampled and, after low pass filtering to prevent aliasing, the signals were fed into a fast Fourier transformation analyzer. Finally, FOT parameters, impedance (Zrs), respiratory resistance at 5 Hz, 20 Hz and 35 Hz (R5Hz, R20Hz, R35Hz respectively), reactance at 5 Hz (X5Hz) and resonant frequency (Fres), were calculated and measured from each impulse.

Lung volumes and flows were measured in the sitting position, using the same device, after FOT. For each patient, spirometry was performed 3 times and the best value for FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), PEF and MMEF (maximal mid-expiratory flow rate) from three flow-volume curves were selected.

3. Nonspecific Airway Hyperresponsiveness

Nonspecific airway hyperresponsiveness was determined by methacholine challenge with a modified method of Chai et al.12). Methacholine was diluted to physiologic saline and delivered by dosimeter (DSM-2, S&M Instrument Company Inc., Doylestown, PA, USA). Each patient took 5 full inhalations from functional residual capacity. The initial concentration of methacholine administration was 0.075 mg/mL and a dose response curve was constructed by administering doubling concentrations of methacholine up to 25 mg/mL. Provocational concentrations of methacholine used to produce a 20% decrease in FEV1 from the baseline value, M-PC20, was calculated by linear interpolation between the last two points on the dose response curve.

4. Statistical Analysis

The SPSS statistical package 8.0 was used to analyze the data. Pearson’s correlation was used to assess the association between FOT and spirometry parameters. Geometric mean of M-PC20 and serum IgE was calculated from logarithmic transformation of each value. Comparisons of eosinophil counts, serum IgE, M-PC20, spirometry parameters and FOT parameters according to asthma severity group were analyzed by ANOVA. Using Pearson’s correlation, we estimated reproducibility of FOT and spirometry measurements by comparison of the same parameters of two repeated tests. All values are expressed as mean± standard deviation, and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

1. Features of Enrolled Patients

Table 1 shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients according to asthma severity. There was no significant difference in age, height, weight, serum IgE and sputum eosinophil counts between each group. Airway hyperresponsiveness was significantly increased along with asthma severity, and lung functions measured by spirometry showed significant difference between each group.

2. FOT Parameters in Patients with Asthma

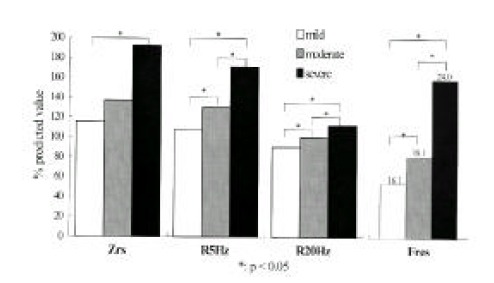

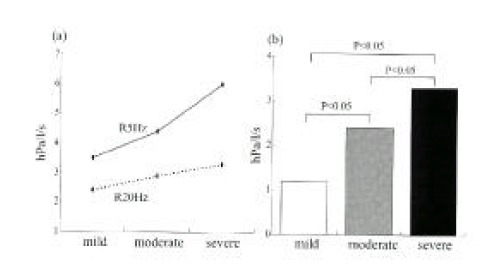

Resonant frequency, resistance at 5 Hz and 20 Hz showed significant difference between each group (p<0.05) (Table 2). There were significant higher values of impedance in the severe asthma group than in the mild (p<0.05). Resistance at 35 Hz had a tendency to increase as severity increased, but statistical significance was not found (p>0.05) (Figure 1). In contrast to the relative constancy of resistance at different frequencies in healthy subjects, resistance is increased at the lower applied frequencies but falls with increasing frequencies in patients with intrapulmonary airway obstruction13). This reflects the presence of inhomogeneity of pulmonary mechanical properties. Based on this point, we calculated resistance difference at 5 Hz and 20 Hz (R5Hz–R20Hz) as a parameter of airway obstruction. This parameter showed statistically significant difference between each asthma group (p<0.05) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of FOT parameters according to asthma severity

| Asthma severity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild (n=111) | Moderate (n=78) | Severe (n=27) | |

| Resonant frequency (Fres, Hz)* | 16.1±4.7 | 18.1±5.8 | 24.0±6.9 |

| Impedance (Zrs, pred %)† | 115.6±53.2 | 137.2±61.4 | 191.9±90.5 |

| Resistance at 5 Hz (R5Hz, pred %)* | 108.1±49.9 | 130.1±59.7 | 171.5±78.2 |

| Resistance at 20 Hz (R20Hz, pred %)* | 90.3±34.5 | 100.6±37.3 | 112.8±42.1 |

| Resistance at 35 Hz (R35Hz, pred %) | 42.4±4.0 | 47.7±5.4 | 51.0±9.8 |

| R5Hz – R20Hz (hPa/l/s)* | 1.2±1.1 | 2.4±1.1 | 3.3±2.1 |

p<0.05: between each group.

p<0.05: between mild and severe group.

R5Hz–R20Hz: resistance difference at 5 Hz and 20 Hz (R5Hz–R20Hz).

Figure 1.

Comparisons of FOT parameters according to asthma severity. Impedance (Zrs), resistance at 5 Hz and 20 Hz are described as % predicted value. Values of resonant frequency (Fres) are marked at the top of each bar.

Figure 2.

Resistance difference at 5 Hz and 20 Hz. Resistance is increased according to asthma severity both at 5 Hz and at 20 Hz (a). There is significant difference of resistance difference at 5 Hz and 20 Hz between each group (b).

3. Association between FOT and Spirometry Parameters

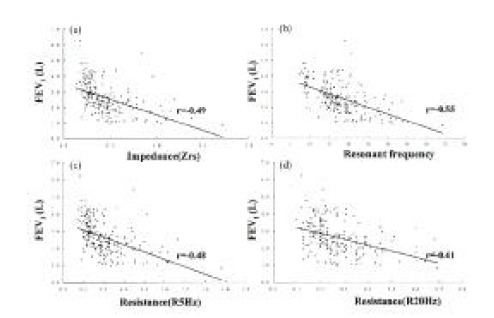

Resonant frequency measured by FOT and FEV1 by spirometry showed good inverse correlation (r=−0.55, p<0.01). Comparison of Zrs, R5Hz and R20Hz with FEV1 also showed significant correlation (p<0.05, respectively) (Figure 3). Relationships between FOT parameters and MMEF in 156 patients with FEV1 more than 80% of predicted value were still significant, but slightly lower compared with associations between FOT parameters and FEV1 (Table 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation between FEV1 and impedance (a), resonant frequency (b), resistance at 5 Hz (c), and resistance at 20 Hz (d). Each correlation shows statistically significant relationship (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Correlation between FOT and Spirometry Parameters

| FEV1 (n=216) | MMEF† (n=156) | |

|---|---|---|

| Impedance (Zrs) | −0.49* | −0.34* |

| Resonant frequency (Fres) | −0.55* | −0.37* |

| Resistance at 5 Hz (R5Hz) | −0.48* | −0.35* |

| Resistance at 20 Hz (R20Hz) | −0.41* | −0.36* |

| Resistance at 35 Hz (R35Hz) | −0.35* | −0.32* |

p <0.05

measured for subjects with normal pulmonary function (FEV1≥80%).

4. Reproducibility of FOT Measurements

We estimated reproducibility of FOT and spirometry measurements by comparison of the same parameters of repeated tests which were performed two times separately (mean interval; 6 months) in patients with no severity changes. Correlation of FEV1 between two measurements was 0.79 and similar to that of R5Hz (r=0.78). Zrs, resonant frequency, R20Hz and R35Hz also showed significant reproducibility, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reproducibility of FOT Parameters in Subjects with no Severity Change

| Correlation coefficient | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| FEV1 (L) | 0.79 | < 0.01 |

| Impedance (Zrs, hPa/l/s) | 0.49 | < 0.05 |

| Resonant frequency (Fres, Hz) | 0.47 | < 0.05 |

| Resistance at 5 Hz (R5Hz, hPa/l/s) | 0.78 | < 0.01 |

| Resistance at 20 Hz (R20Hz, hPa/l/s) | 0.65 | < 0.01 |

| Resistance at 35 Hz (R35Hz, hPa/l/s) | 0.81 | < 0.01 |

| Reactance at 5 Hz (X5Hz, hPa/l/s) | 0.18 | > 0.05 |

n=20, mean time interval of repeated test: 6 months.

DISCUSSION

Classification of asthma severity is based on the degree of airway hyperresponsiveness, eosinophil counts and/or eosinophil cationic protein levels in blood or sputum, and lung functions. Measurements of lung function are objective and easily available method to assess airway obstruction, and are recommended as useful criteria for the assessment of asthma severity by recent guidelines11). Spirometry is the standard method for measurements of lung function and its validity, reproducibility and responsiveness is well verified1). Of the several parameters in spirometric measurements, FEV1 is the most sensitive and reproducible index to detect airway obstruction14). MMEF is effort independent and partially reflects small airway obstruction, but its sensitivity and reproducibility is lower than FEV114). Occasionally, spirometric measurement of lung function is difficult due to lack of patient’s cooperation. Whole body plethysmography is another useful technique to measure airway resistance, but it also needs the patient’s cooperation3).

FOT is an alternative method to overcome these problems, because it requires only passive cooperation. The basic principle of FOT is measurement of the relationship between pressure waves applied externally to the respiratory system and the resulting respiratory air flow6). The ratio of the amplitude of the pressure wave to the amplitude of the flow wave constitutes the impedance, and then it is further analyzed into resistance (Rrs) and reactance after Fourier transformation5, 6).

Respiratory resistance is relatively constant at different frequencies in healthy subjects, but it is increased at the lower applied frequencies but falls with increasing applied frequencies in patients with airway obstruction13). This resistance fall with increasing frequency is a result of the presence of inhomogeneity of pulmonary mechanical properties, and is an expected and similar finding in both asthma and chronic obstructive lung disease. Values of reactance are negative at lower frequencies, and progressively increase and become positive at higher frequencies. The frequency at which reactance becomes zero is resonant frequency, and it is increased in proportion to the degree of the airway obstruction. So, these parameters are usefully applied to assess the degree of the airway obstruction5, 15, 16).

In this study, we tried to estimate the clinical usefulness of FOT in the classification of asthma severity. We did not differentiate patients with mild intermittent asthma from mild persistent asthma, because both groups showed the same range of spirometry measurements, and FOT could not classify mild asthma into two distinct groups in our unpublished data. We also included smokers in this study, because FOT difference between smokers and non-smokers was not found in our analysis (data not shown) and in a previous report by Landser et al.17).

As expected, the degree of the airway hyperresponsiveness and spirometric measurements of lung function showed significant difference according to asthma severity, and these are quite reasonable because we divided the patients into 3 severity groups with mainly FEV1 criteria. Sputum eosinophil counts, however, were lower in the severe group than in the less severe group. These findings might be the results from treatments of systemic or high doses inhaled corticosteroid and consequent suppression of eosinophils in the severe group18).

In general, resistance at lower frequency is a very sensitive index to detect airway obstruction19). In our study, R5Hz, R20Hz and resonant frequency of FOT measurements showed significant difference according to asthma severity as spirometry parameters. Respiratory impedance in the severe group was also higher than in the mild group. Based on the frequency dependency of resistance, we calculated a new index, resistance difference between two different frequencies (resistance at low frequency - resistance at relatively high frequency), to determine the inhomogeneity of mechanical properties of the obstructed lungs. Such an index, R5Hz–R20Hz, also showed significant difference between each group and was considered as a useful parameter of FOT. But it is still a conceptual meaning, and further studies will be needed to clearly define its value and significance.

Several studies compared FOT with spirometry and/or whole body plethysmography in the assessment of airflow obstruction. Airway resistance measured by FOT (Rrs) and body plethysmography (sRaw) showed good correlation, but relationships between FOT and FEV1 or MMEF were variable according to each study design5, 8, 13, 20). In this study, FOT parameters had significant association with FEV1, and with MMEF in patients with normal pulmonary function. Considering correlation coefficient, however, their association was not strong, and such result was not surprising because each parameter measured its own peculiar part of the respiratory mechanics. We also estimated reproducibility of FOT by comparing the repeated tests performed at 6 months interval in patients with the same clinical condition. The correlation coefficient of R5Hz was 0.78 and very similar with that of FEV1 (r=0.79). Therefore we can consider that resistance measured by FOT, especially at low frequency, is a highly reproducible index and compatible with FEV1.

In spite of some attractive advantages of FOT, it has still several limitations in clinical practice5). The first is that measurements of FOT are influenced by the extrathoracic upper airway artifact. That is, the pressure-flow properties of the upper airway may play a role in determining the total respiratory impedance. To overcome this problem, we advised patients to support their cheeks with their palms, but these methods cannot eliminate upper airway artifact totally. Recently, Farre et al.21) suggested that change of FOT admittance, not standard generator but head generator, can minimize artifact caused by the upper airway. So it is expected that further development and progress of FOT will take off such an artifact. The second limitation is lack of reference values of each FOT parameter for Korean subjects, because it is being used rather lately in clinical practice, and the number of reports of normal values for oriental people is limited. The third limitation is that it is not effectively sensitive to detect the pathologic conditions of chest wall and restrictive lung diseases. Moreover, the significance of parameters measured at higher frequencies is not clear yet. Finally, some parameters have still not been employed widely because of their obscure meaning. For example, FOT can divide respiratory resistance into two compartments, central resistance and peripheral resistance, but fractionating criteria is not an anatomical structure but a theoretical conception. Therefore such parameters have to be explained clearly based on scientific researches before clinical practice.

In conclusion, FOT is a non-invasive, effort-independent, and easily applicable method to detect airway obstruction in bronchial asthma, and is a useful and alternative method for evaluating the clinical status of patients with asthma. Because asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized with various clinical and laboratory features, a physician cannot understand a patient’s condition exactly by only one criterion. In this situation, measurements of FOT can be added to other conventional criteria. Further investigations may expand FOT applications in various clinical conditions and diseases.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Thoracic Society Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quanjer PH, Tammeling GJ, Cotes JE, Pedersen OF, Peslin R, Yernault JC. Lung volumes and forced ventilatory flows. Report Working Party Standardization of Lung Function Tests, European Community for Steel and Coal. Official Statement of the European Respiratory Society. Eur Respir J. 1993;6(Suppl. 16):5–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pride NB. Forced oscillation technique for measuring mechanical properties of respiratory system. Thorax. 1992;47:317–320. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DuBois AB, Brody AW, Lewis DH, Burgess BF., Jr Oscillation mechanics of lungs and chest in man. J Appl Physiol. 1956;5:587–594. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1956.8.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demedts M, Van Noord JA, Van de Woestijne KP. Clinical applications of forced oscillation technique. Chest. 1991;99:795–797. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landser FJ, Nagels J, Demedts M, Billiet L, Van de Woestijne KP. A new method to determine frequency characteristics of the respiratory system. J Appl Physiol. 1976;41:101–106. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desager KN, Buhr W, Willemen M, van Bever HP, de Backer W, Vermeire PA, Landser FJ. Measurement of total respiratory impedance in infants by the forced oscillation technique. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71:770–776. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.2.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klug B, Bisgaard H. Measurement of lung function in awake 2–4 year-old asthmatic children during methacholine challenge and acute asthma: a comparison of the impulse oscillation technique, the interrupter technique, and transcutaneous measurement of oxygen versus whole-body plethysmography. Pediatr Pulm. 1996;21:290–300. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0496(199605)21:5<290::AID-PPUL4>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ducharme FM, Davis GM. Measurement of respiratory resistance in the emergency department: feasibility in young children with, acute asthma. Chest. 1997;111:1519–1525. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Noord JA, Clement J, van de Woestijne KP, Demedts M. Total respiratory resistance and reactance as a measurement of response to bronchial challenge with histamine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:921–926. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.4.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, NIH Expert Panel report II: guidelines for the diagnosis and maangement of asthma. 1997.

- 12.Chai H, Farr RS, Froehlich LA, Mathison DA, McLean JA, Rosenthal RR, Sheffer AL, Spector SL, Townley RG. Standardization of bronchial inhalation challenge procedures. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1975;56:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(75)90107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zerah F, Lorino AM, Lorino H, Harf A, Macquin-Mavier I. Forced oscillation technique vs spirometry to assess bronchodilation in patients with asthma and COPD. Chest. 1995;108:41–47. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminsky DA, Irvin CG. Lung function in asthma. In: Barnes PJ, Gunstein MM, Leff AR, Woolcock AJ, editors. Asthma. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. P1277–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ducharme FM, Davis GM. Respiratory resistance in the emergency department: A reproducible and responsive measure of asthma seventy. Chest. 1998;113:1566–1572. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.6.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayes DA, Pimmel RL, Fullton JM, Bromberg PA. Detection of respiratory mechanical dysfunction by forced random noise impedance parameters. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120:1095–1100. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.5.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landser FJ, Clement J, Van de Woestijne KP. Normal values of total respiratory resistance and reactance determined by forced oscillations. Chest. 1982;81:586–591. doi: 10.1378/chest.81.5.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kips JC, Peleman RA, Pauwels RA. Methods of examining induced sputum: do differences matter? Eur Respir J. 1998;11:529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Noord JA, Clement J, Van de Woestijne KP, Demedts M. Total respiratory resistance and reactance in patients with asthma, chronic bronchitis, and emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143:922–927. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozen D, Bracamonte M, Sergysels R. Comparison between plethysmography and forced oscillation techniques in the assessment of airflow obstruction. Respiration. 1983;44:197–203. doi: 10.1159/000194549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farre R, Rotger M, Marchal F, Peslin R, Navajas D. Assessment of bronchial reactivity by forced oscillation admittance avoids the upper airway artefact. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:761–766. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.13d11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]