Abstract

Gold salts have been used for many years in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. The common side effects are mucocutaneous reactions, but hepatotoxic reaction and isolated neutropenia are rare complications. We report a 62-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis who had developed hepatitis and neutropenia simultaneously after receiving 137.5 mg of sodium aurothiomalate.

Keywords: Gold, Hepatitis, Neutropenia, Rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

INTRODUCTION

Gold salts are important disease modifying antirheumatic drugs in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, toxicities with injectable gold are common, occuring in about 30–40% of patients with RA in the long-term use of gold salts1). The most common side effect of gold salts is mucocutaneous reactions, such as dermatitis, mouth ulcers or pruritus, which account for 60–80% of all gold-associated toxicities1). Other side effects are vasomotor reactions, proteinuria and bone marrow suppression.

Hepatotoxicity and isolated neutropenia which were developed simultaneously after gold therapy is a rare complication. We report a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who developed an unusual combination of hepatotoxic reactions and neutropenia as side effects of injectable gold.

CASE

A 62-year-old woman with a 9-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) was admitted to our hospital due to swelling and pain of both knees for several months, despite receiving antirheumatic drugs. There had been no history of any hepatic disease. The patient denied excessive alcohol consumption and taking any other medicine recently. She had an allergy to barbiturates and diabetes mellitus for 3 years, managed with metformin.

The temperature was 37°C, the pulse was 70 /minute, the respiration was 17 /minute and the blood pressure was 140/90 mmHg. There were no significant changes in vital signs after gold injections.

Physical examination revealed swelling, heat and redness of the wrists and knees at the time of admission. Also the wrists and knees showed some restricted range of motions. There were no signs of rash, splenomegaly and icterus. The liver was not tender and also not enlarged.

Screens of hematological and biochemical profiles, including liver function, revealed normal except normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin concentration 9.5 mg/dL), thrombocytosis (566,000 /mm3) and elevated alkaline phosphotase level (218 IU/l, reference value 30–110). Alkaline phosphotase level had been elevated above normal level persistently before gold injections. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 57 mm/h by the Wintrobe method, and rheumatoid factor estimation by nephelometric method revealed 88 IU/mL (reference value < 20). The C-reactive protein was 10.6 mg/dL (reference value < 0.8). X-ray examination of the hands revealed erosions and partial bony fusions involving both wrists. Radiographs of the knees showed effusion, erosions, periarticular osteoporosis, narrowing of the joint spaces and osteophytes at the articular margins. Ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen showed no hepatic and splenic abnormalities.

She had been managed with sulfasalazine (1 g/day), bucillamine (200 mg/day), piroxicam (20 mg/day), triamcinolone (2 mg/day) in stable dosages and intermittent intra-articular corticosteroid injections.

It was decided to commence treatment with gold injection and she was tested with 12.5 mg of intramuscular sodium aurothiomalate and administered 25 mg of gold on the next day inadvertently. After that, aurothiomalate was given twice at a weekly dose of 50 mg (total cumulative dose 137.5 mg). Although her arthritic symptoms had improved a little bit, she complained of malaise, dyspepsia, nausea and transient pruritus. There was no evidence of jaundice, petechial hemorrhage or skin infections. After injection of the last dose, transient palmar erythema was noticed on both palms. All symptoms and signs disappeared 3 days after each gold injection. These symptoms were considered mild and had required no additional treatment.

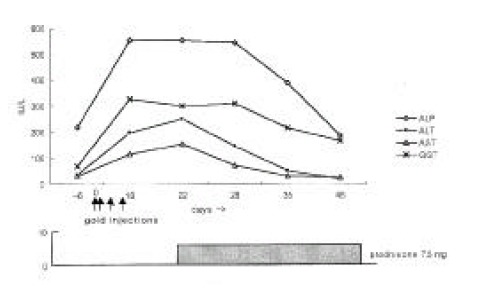

Laboratory examinations after the last gold injection showed a leukocyte count of 2,200 /mm3 (differentiation: 79% neutrophils, 18% lymphocytes, 2% monocytes, 0% eosinophils, 1% basophils), normochromic anemia (hemoglobin concentration 9.4 mg/dL, mean corpuscular volume 88 fl) and normal platelet count (376,000 /mm3). Liver function tests revealed elevated liver enzyme levels without hyperbilirubinemia (Figure 1). Prothrombin time was normal. Additional laboratory examinations yielded no evidence of hepatitis A, B or C, cytomegalovirus or Epstein-Barr virus infection. Antinuclear antibodies and liver disease specific antibodies such as anti-mitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle and anti-liver-kidney microsomal 1 (LKM1) antibodies were negative. Serum immunoglobulin levels were the following: immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1260 mg/dL (reference value 751–1560), IgA 231 mg/dL (reference value 82–453), IgM 112 (reference value 46–304), IgD 11 IU/mL (reference value < 100) and IgE 3.4 IU/mL (reference value 0–200).

Figure 1.

Changes of the liver function tests in our patient. Day 0 was the day of first gold injection. Abbreviations: ALP; alkaline phosphatasem, ALT; alanine-amino transferase, AST; aspartate-amino transferase, GGT; gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase

Therapy consisted of discontinuation of potentially hepatotoxic drugs (aurothiomalate, sulfasalazine, bucillamine, piroxicam, metformin) and a treatment with prednisone 7.5 mg/day. Approximately six weeks after cessation of gold injection, liver function tests became normalized except for alkaline phosphotase level, and then sulfasalazine, bucillamine, piroxicam, triamcinolone and metformin were resumed. In addition, neutropenia was recovered to 6,900 /mm3 at 5 weeks after cessation of gold injections (Figure 2). She has had an uneventful recovery and her arthritis of the knees was treated by total knee replacement.

Figure 2.

Changes of the WBC, hemoglobin and platelet. Day 0 was the day of first gold injection. Abbreviations: WBC; white blood cell

DISCUSSION

Forestier in 1929 pioneered the use of gold for the treatment of RA, assuming that both conditions might have a common infectious cause2). The benefit of gold treatment in RA has been well documented over the past years. However, less than 50% of patients treated with parenteral gold remain on gold after 5 years, with approximately 60% of terminations of treatment attributable to toxicity3). Adverse reactions develop in about one third of patients with RA treated with injectable gold. Most complications are trivial, consisting primarily of localized dermatitis, stomatitis, transient hematuria, and mild proteinuria1). More serious adverse reactions include the hematopoietic system, kidneys, liver or other vital organs.

A systematic search of the English literature for the last 30 years yielded less than 30 documented cases of gold related hepatotoxicity. In most patients, the hepatic damage appeared during the early stages of gold therapy and after relatively small total doses. Most cases showed cholestasis with jaundice, pruritus, rash, fever and abdominal complaints.

Boekhorst et al. summarized 24 well-documented cases of gold salt related hepatotoxicity in the English literature for the last 30 years4). Liver biopsies were done from 17 of the 24 cases. They consisted of 11 patients with cholestasis, 2 patients with hepatitis, 3 patients with necrosis, 1 patient with pericholangitis and 1 patient with cholestasis and necrosis together. Seven patients, the remainder, did not have liver biopsies. All except one patient survived and liver function was restored in all cases. The patient with a fatal outcome died of pulmonary insufficiency due to bronchopneumonia and fibrosing alveolitis.

The mechanism underlying hepatotoxicity of gold remains unknown. Two possible mechanisms have been proposed. The first is an idiosyncratic side effect that is not dose-related and occurs even after small doses of gold5–8). The concomitant skin rash, eosinophilia and increased IgE levels support this theory. The second mechanism is a direct toxicity due to gold accumulation in the lysosomes of hepatic macrophage9). This mechanism is dose related and occurs late in the course of therapy, without biochemical or structural evidence of cholestasis. The relevance of this finding is, however, unclear since uncomplicated gold therapy also results in gold accumulation in many organs, especially in cells of the reticuloendothelial system in the liver and kidney10, 11)

In previous reports, therapy for gold-induced hepatotoxicity has always consisted of discontinuation of the drug. Sometimes corticosteroids, including our own, were started either to minimize liver damage or to control RA activity. The overall outcome in gold induced hepatotoxicity seems favorable.

Other rare complications of gold are hematologic complications that include eosinophilia, leukopenia or agranulocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, pancytopenia, and aplastic anemia. The most feared complication is severe pancytopenia or bone marrow aplasia with reported mortality of 61–80%12–14). In the past, the mortality rate was very high, but prognosis has been improved by aggressive therapy, including bone marrow transplantation, antithymocyte globulin or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. The prevalence of leukopenia is low, and the extent and duration of white cell reductions are variable. Twenty-five cases were reviewed for neutropenia during chrysotherapy15). They were divided into 3 groups according to commonly used clinical criteria: 3 patients developed Felty’s syndrome, 8 gold myelotoxicity and 14 mild, chronic benign granulocytopenia. Six of the 8 patients with gold myelotoxicity had pancytopenia with anemia and thrombocytopenia. Isolated leukopenia developed in 2 of the 8 patients with gold myelotoxicity. The mechanisms involved in gold induced marrow suppression are unclear but include a direct toxic effect and an immune etiology.

To our knowledge, there is only one previous case report that demonstrated hepatitis and neutropenia simultaneously secondary to gold thiomalate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis16).

In our case, hepatitis without jaundice and neutropenia after gold injection developed concurrently in the early phase of gold injections. Although most hepatic injury after gold injections is associated with cholestatsis, there was no jaundice but hepatitis was dominant in our case. Liver biopsy and bone marrow biopsy were not done because clinical symptoms and serologic signs were mild and showed improvement with time. The isolated neutropenia in our case was abrupt onset and occurred in the early times of gold injections, and also showed rapid recovery. So it was possible that in our patient, gold might act as a mild bone marrow depressant. We had prescribed piroxicam, bucillamine, sulfasalazine and metformin for about 3 years, but they were less likely to cause any hepatic problems and isolated neutropenia, as those drugs were continued throughtout the patient’s illness.

In conclusion, hepatotoxicity and isolated neutropenia on gold therapy are very rare but well-documented side effects. Discontinuation of gold administration is usually followed by complete recovery. Close observation for these complications should be considered, especially in the early phase of gold injections.

REFERENCES

- 1.Day RO. SAARDs. In: Klippel JH, Dieppe PA, editors. Rheumatology. 2nd ed. London: Mosby; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kean WF, Forestier F, Kassam Y, Buchanan WW, Rooney PJ. The history of gold therapy in rheumatoid disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1985;14:180–186. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(85)90037-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richer JA, Runge LA, Pinals RS, Oates RP. Analysis of treatment terminations with gold and antimalarial compounds in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1980;7:153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.te Boekhorst PA, Barrera P, Laan RF, van de Putte LB. Hepatotoxicity of parenteral gold therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: A case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1999;17:359–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Favreau M, Tannenbaum H, Lough J. Hepatic toxicity associated with gold therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1977;87:717–719. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-87-6-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenker S, Olson KN, Dunn D, Breen MB, Combes B. Intrahepatic cholestasis due to therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Gastroenterology. 1973;64:622–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelman J, Donelly R, Graham DN, Percy JS. Liver dysfunction associated with gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1983;10:510–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schapira D, Nahir M, Scharf Y, Pollack S. Cholestatic jaundice induced by gold salts treatment: Clinical and immunological aspects-report of one case and a review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1984;11:843–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gishan FK, Labrecque DR, Younoszai K. Intrahepatic cholestasis after gold therapy in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Pediatr. 1978;93:1042–1043. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)81255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pressayre D, Feldman G, Degott C, Ulmann A, Roger W, Erlinger S, Benhamou JP. Gold salt-induced cholestasis. Digestion. 1979;19:56–64. doi: 10.1159/000198323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howrie DL, Gartner JC. jr. Gold-induced hepatotoxicity: Case report and a review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:727–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarty DJ, Brill JM, Harrop D. Aplastic anemia secondary to gold salt therapy. Report of a fatal case and review of literature. J Am Med Assoc. 1962;179:655–657. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay AGL. Myelotoxicity of gold. Br Med J. 1976;1:1266–1268. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6020.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson J, McGirr EE, York J, Kronenberg H. Aplastic anemia in association with gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Aust NZ J Med. 1983;13:130–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1983.tb02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aaron S, Davis P, Percy J. Neutropenia occurring during the course of chrysotherapy: A review of 25 cases. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:897–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MD. Hepatitis and neutropenia secondary to gold thiomalate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Aust NZ J Med. 1986;16:72–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1986.tb01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]