Abstract

Purpose

Ovarian aging is closely tied to the decline in ovarian follicular reserve and oocyte quality. During the prolonged reproductive lifespan of the female, granulosa cells connected with oocytes play critical roles in maintaining follicle reservoir, oocyte growth and follicular development. We tested whether double-strand breaks (DSBs) and repair in granulosa cells within the follicular reservoir are associated with ovarian aging.

Methods

Ovaries were sectioned and processed for epi-fluorescence microscopy, confocal microscopy, and immunohistochemistry. DNA damage was revealed by immunstaining of γH2AX foci and telomere damage by γH2AX foci co-localized with telomere associated protein TRF2. DNA repair was indicated by BRCA1 immunofluorescence.

Results

DSBs in granulosa cells increase and DSB repair ability, characterized by BRCA1 foci, decreases with advancing age. γH2AX foci increase in primordial, primary and secondary follicles with advancing age. Likewise, telomere damage increases with advancing age. In contrast, BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells of primordial, primary and secondary follicles decrease with monkey age. BRCA1 positive foci in the oocyte nuclei also decline with maternal age.

Conclusions

Increased DSBs and reduced DNA repair in granulosa cells may contribute to ovarian aging. Discovery of therapeutics that targets these pathways might help maintain follicle reserve and postpone ovarian dysfunction with age.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10815-015-0483-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Ovarian aging, DNA double-strand break, Rhesus monkey, BRCA1

Introduction

Primordial follicles with associated primary oocytes form before birth, and after puberty they grow to form primary, secondary and antral follicles. Only few follicles ovulate during the human reproductive life span and most undergo atresia. The ovary contains one million primordial follicles at birth, but follicle reservoir declines about 1000 follicles each month during adulthood [1, 2]. By age 50 ovarian reserve is nearly completely exhausted [3]. Unlike males having germline stem cells and germ cell renewal, females do not contain germline stem cells and do not undergo germ cell renewal [4–7], resulting in a limited reproductive lifespan. Women undergo follicle depletion and experience menopause by the age of approximately 50.

During the reproductive lifespan in women, follicles in the reserve can remain dormant up to 50 years. All cells, including oocytes and granulosa cells, are subjected to DNA damage with age. However, oocytes can repair DNA damage induced by a variety of factors, including meiotic recombination, UV and X-irradiation or mutagenic chemicals [8]. Studies using autoradiography assay show that mouse oocytes do not experience increased DNA damage with age, and the oocyte’s capacity to repair UV-induced damage is maintained at a high level throughout reproductive life [9]. More recent studies show that chemotherapeutic agents can induce DSBs in human oocytes [10, 11], and DNA damage double-strand break (DSBs) repair is impaired in oocytes with advancing maternal age, perhaps contributing to the reduced developmental competence of oocytes with advancing age [12].

Aneuploidy increases in oocytes and embryos with advancing maternal age [13]. DNA damage at telomeres could contribute to telomere attrition, contributing to non-disjunction, miscarriage and Downs syndrome [14–16]. Old mouse oocytes show shorter telomeres than those of young oocytes [17]. Short telomeres also reduce homologous pairing and recombination, and cause meiotic abnormality including aberrant chromosome alignment at metaphase and disruption of spindles, resulting in aneuploidy [18–20].

In addition to decreasing oocyte and follicle number, the microenvironment within follicles and ovaries also could deteriorate with age. Particularly, granulosa cells and cumulus cells are intimately connected with oocytes, and both play critical roles in oocyte growth and follicular development [21–23]. Development of a competent oocyte depends on the maintenance of homeostasis in the ovarian and follicular microenvironment. The state of granulosa cells is closely linked to the developmental competence of the oocyte [24]. Telomere length in cumulus cells may serve as a biomarker of oocyte and embryo quality [25]. Although granulosa cells show characteristics of somatic stem cells [6, 26], these cells still undergo telomere shortening with age [27], possibly due to long-term exposure to reactive oxygen species, impairment in cellular physiology and gradual decreasing numbers of follicles [28]. Stem cell dysfunction provoked by telomere shortening may be one of the mechanisms responsible for organismal aging in both humans and mice [29]. In addition, cellular senescence triggered by multiple mechanisms, including telomere shortening and DNA damage, may be involved in aging [30]. Other somatic cell compartments also could degenerate with age, and these deteriorating niches may not be suitable for oocyte development. Further understanding the mechanisms underlying DNA damage and repair within the follicular compartment may help identify specific targets to prolong ovarian function with age.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are members of a family of genes that play critical roles in DSB repair [12, 31, 32]. BRCA1 is recruited to sites of double-strand breaks [33]. Mutations in the BRCA gene markedly increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer [34, 35]. BRCA1 mutation also can contribute to premature menopause [36]. In addition, chemotherapy or aging increases DSBs in mouse and human germ cells and granulosa cells, and DSB repair maintains ovarian reserve and prevents DNA damage induced ovarian premature aging [11, 12, 37]. Moreover, BRCA1/2 is involved in telomere maintenance [33, 38–41].

The Rhesus monkey is the experimental animal most closely related to human beings. Reproductive physiology and aging in Rhesus monkeys closely model these processes in women [42]. Rhesus monkeys live about 35 years, reach puberty at 3–5 years old, ovulate one egg each month, and maintain fertility for about 20 years, after which follicle numbers decline, and menopause ensues [43, 44]. We tested the hypothesis that DNA damage increases and the DNA repair protein BRCA1 decreases in granulosa cells with advancing age in the Rhesus monkey.

Materials and methods

Collection of tissues

General care and housing of rhesus monkeys were provided at Guangxi Xiong Sen Primate Experimental Animal Development Corporation. Use of monkeys for this study and the protocol for collecting monkey tissues were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Nankai University. Female monkeys were randomly chosen from three groups according to their reproductive ages at 3–4 years (young), 7–8 years (middle-aged) and 18–19 years (old), with three monkeys in each age group. Rhesus monkeys were euthanized, and ovaries collected. The monkeys were not at menstrual phase when the materials were collected. Half of each ovary was fixed in 4 % paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature and then embedded in paraffin. Another half of each ovary was cut into small pieces, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for RNA and DNA extraction.

Immunocytochemistry and fluorescence microscopy

The method for immunofluorescence microscopy was described [6], but with different antibodies used here. Briefly, after de paraffinizing, rehydrating and washing in 0.01 M PBS (pH 7.2–7.4), sections were incubated with 3 % H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase, subjected to high pressure antigen recovery sequentially in 0.01 % citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 3 min, incubation with blocking solution (5 % goat serum in PBS) for 2 h at room temperature, and then with the diluted primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Blocking solution without the primary antibody served as negative control. After washing with PBS, sections were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor®488 or 594, Invitrogen), then stained with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 for 10 min to reveal nuclei, washed, mounted in Vectashield (H-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, US), and photographed with a Zeiss Axio Imager Z1 (Carl Zeiss). Confocal images were captured using Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. The following primary antibodies were used for immunocytochemistry: γH2AX (4411-pc-020, TREVIGEN, 1:400), TRF2 (05–521, Millipore, 1:400), and BRCA1 (SC-28234, Santa Cruz, 1:200).

Foci counts

Fixed specimens were dehydrated with graded alcohols, cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin wax. Serial 5 μm sections of half of each ovary were cut and placed on silanized slides. Sections were co-immunostained with γH2AX and TRF2 or BRCA1, and analyzed for the number of foci in different cells. Follicles were classified into different category depending on their developmental stages [45]. Primordial, primary and intermediate-stage (compact or enlarged oocyte with a single layer of mixed flattened and cuboidal granulosa cells) follicles were identified by the presence of an oocyte surrounded by a single layer of flat, squamous or cuboidal granulosa cells. Secondary growing follicles were characterized as having more than one layer of granulosa cells with no visible antrum. Antral follicles possessed small areas of follicular fluid (antrum) or a single large antral space (Fig. S1 and 3a). Cortex somatic cells were cells in ovary cortex other than follicles and blood cells.

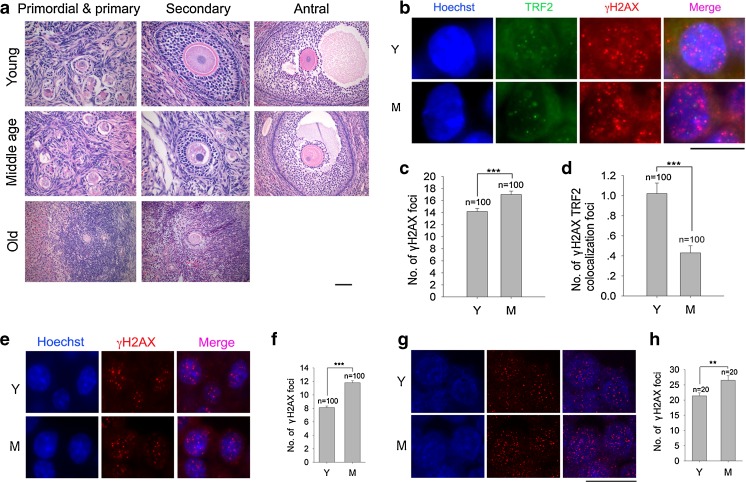

Fig. 3.

DSBs and telomeres in granulosa cells or cumulus cells of antral follicles in adult monkey ovaries by co-immunostaining of γH2AX and TRF2, or only γH2AX. a Histology showing granulosa cells in the primordial & primary, secondary and mature antral follicles of monkey ovaries. Scale bar = 50 μm; Note, antral follicles are rarely found in old monkey ovaries, so not available for analysis. b Representative morphology of single granulosa cell in antral follicles in the ovaries of young and middle-age monkeys. c Number of γH2AX foci in granulosa cells of antral follicles. d Number of γH2AX and TRF2 co-localization foci in granulosa cells of antral follicles. Scale bar = 10 μm; Error bars show mean + SEM. ***P < 0.001. n = number of cells counted. e-h Immunostaining and confocal imaging analysis of γH2AX foci in the cumulus cells of healthy antral follicles. e Immunostaining images by epi-fluorescence microscopy of γH2AX foci in cumulus cells of follicles in monkey ovaries. f Average number of γH2AX foci in cumulus cells of healthy antral follicles by epi-fluorescence microscopy. g Confocal images by 3-D reconstruction of γH2AX foci in cumulus cells of follicles in monkey ovaries. h Average number of γH2AX foci in cumulus cells of healthy antral follicles by 3-D reconstruction. e Scale bar = 20 μm, (G) Scale bar = 10 μm; Error bars show mean + SEM. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. n = number of cells counted

We serially sectioned one half of an ovary from each animal and randomly selected eight sections for immunostaining using each antibody on six slides for each monkey age group. Four images at different fields for each follicle category were randomly selected for each slide section, providing a total of 24 images for each follicle category for each monkey age group. Ten follicle images taken from three monkeys were randomly used for counts of foci in granulosa cells and 10 granulosa cells of one randomly selected follicle counted, so total of 100 granulosa cells were counted in most cases for each follicle category by conventional epi-fluorescence microscopy for young and middle-age monkeys (number of cells counted is labeled in the figures).

The Z-serial confocal images of granulosa cells were taken along the Z-axis at a step of 0.5 μm from top to the bottom of each section, and then 3D reconstruction into one image was performed. Counting of foci for confocal images of granulosa cells was the same as described for fluorescence microscopy images.

Immunohistochemistry for detection of BRCA1 by reaction with diaminobenzidine (DAB)

Slides were de paraffinized and rehydrated, incubated in 3 % H2O2 for 10 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase, and incubated sequentially with 5 % goat serum for 2 h after high-pressure antigen recovery, BRCA1 antibody diluted 1:200 in blocking solution at 4 °C overnight, and then HRP polymer-goat anti-rabbit IgG (Maixin_Bio, Beijing, China) for 30 min. Signals were detected by 3,3-diaminobenzidine substrate (Maixin_Bio). Slides were slightly counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, US) and examined using light microscopy. Negative controls were incubated with blocking solution containing no antibody.

Telomere measurement by quantitative real-time PCR

Genomic DNA was extracted from ovaries using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Relative telomere length was measured using quantitative real-time PCR assay, as previously described [46]. PCR reactions were performed on the iCycler iQ real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), using telomeric primers, mTel-F: CGGTTTGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTTTGGGTT, mTel-R: GGCTTGCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCTTACCCT, and primers for the acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein P0 (36B4, single copy gene as reference), 36B4-F: ACTGGTCTAGGACCCGAGAAG, 36B4-R: TCAATGGTGCCTCTGGAGATT. Equal amount (35 ng) of DNA was used for each reaction, and PCR settings (for both telomere and 36B4 products) were as follows: 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. For each PCR reaction, reference DNA sample was diluted by two fold per dilution to produce five concentrations and generated a standard curve. Two separate PCR runs were performed for each sample and primer pair. A point on the standard curve was used as a calibrator.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by ANOVA and means compared by Fisher’s protected least-significant difference (PLSD) using StatView software from SAS Institute Inc. (Cary, NC). P-value <0.05 or lower was considered statistically significant.

Results

Increased DSBs in granulosa cells of follicles with monkey age

Consistently, primordial, primary, and secondary follicles were reduced in ovaries with advancing maternal age (Fig. S1). Only few follicles and rarely antral follicles were found in ovaries of old monkeys.

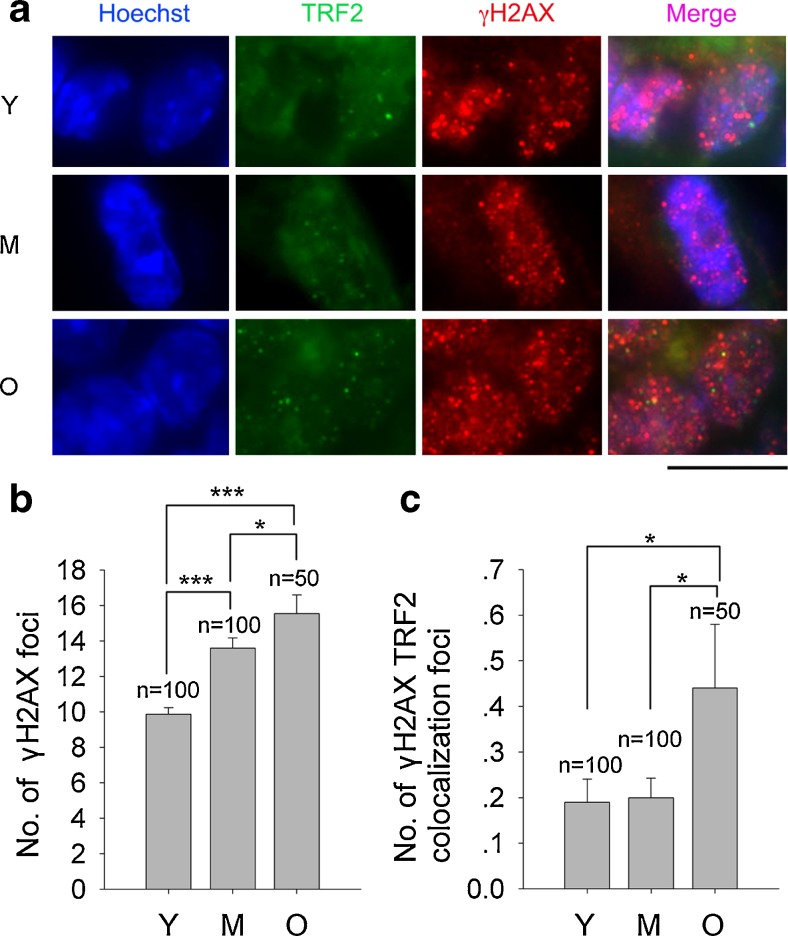

DNA DSBs can be identified by the specific molecular marker γH2AX foci [47]. We examined DNA damage response using γH2AX immunostaining and TRF2 to mark telomeres of ovaries collected from young (3–4 years old, abbreviated as ‘Y’), middle-age (7–8 years old, ‘M’) and old age (18–19 years old, ‘O’) monkeys. DNA damage foci identified by γH2AX increased in granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles with advancing age. Average γH2AX foci were 9.9 ± 0.4, 13.6 ± 0.6, and 15.5 ± 1.0, respectively in ovaries from young, middle age and older monkeys (Fig. 1a and b). Also, DNA damage at telomeres, as shown by γH2AX foci co-localized with TRF2, known as Telomere Dysfunction-Induced Focus (TIF) [48], increased in primordial and primary follicles with advancing monkey age (Fig. 1c). Likewise, DNA and telomere damage foci increased in granulosa cells of secondary follicles with advancing age. The average telomere damage TIF foci for young, middle-age, and old monkeys were 0.6 ± 0.07, 0.3 ± 0.06, and 1.7 ± 0.1, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of markers for DSBs and telomeres in granulosa cells of primordial & primary follicles in adult monkey ovaries by co-immunostaining of γH2AX and TRF2. a Representative morphology of two granulosa cells in primordial & primary follicles in the ovaries of monkeys at various reproductive ages (young, Y, 3–4 years; middle-age, M, 7–8 years; and old, O, 18–19 years). b Number of γH2AX foci in granulosa cells of primordial & primary follicles c Number of γH2AX and TRF2 colocalization foci of primordial & primary follicles. Scale bar = 10 μm; Error bars show mean + SEM. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. n = number of nuclei counted

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence microscopic analysis of markers for DSBs and telomeres in granulosa cells of secondary follicles in adult monkey ovaries by co-immunostaining of γH2AX and TRF2. a Representative morphology of two-three granulosa cells in secondary follicles in the ovaries of monkeys at various reproductive ages. b Number of γH2AX foci in granulosa cells of secondary follicles. c Number of γH2AX and TRF2 colocalization foci in granulosa cells of secondary follicles. Scale bar = 10 μm; Error bars show mean + SEM. ***P < 0.001. n = number of nuclei counted

Old monkeys rarely show antral follicles, so we only compared DSBs only in granulosa cells of antral follicles from young and middle-age monkey ovaries. It appeared that DNA damage was increased in granulosa cells of antral follicles, but telomere damages were reduced from middle-age monkeys, compared with young monkeys (Fig. 3b–d). We also counted DSB foci in cumulus cells of antral follicles from young and middle-age monkeys, as cumulus cells can be distinguishable from mural granulosa cells for antral follicles with clear cavity. DSB foci in cumulus cells increased in middle-age compared to young monkey ovaries (Fig. 3), similar to mural granulosa cells. DNA damage of randomly selected somatic cells in the ovarian cortex does not change as a function of age. Old monkeys did show increased telomere damage in somatic cells (Fig. S2).

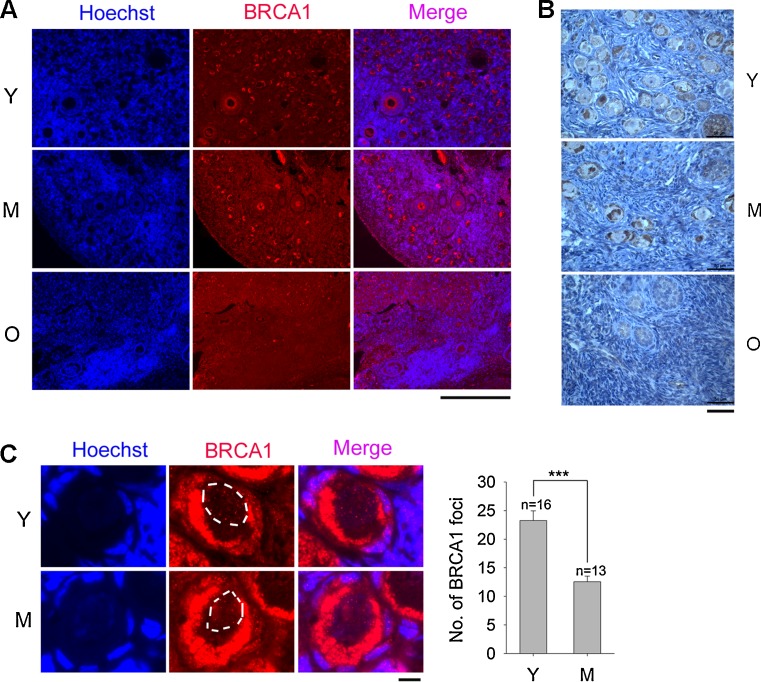

BRCA1 in the oocytes decreases with monkey age

Increased DSBs in granulosa cells and oocytes with maternal age could be related to deficiency of DNA repair. We examined DNA repair by immunostaining for BRCA1 in ovarian sections. Immunostaining of BRCA1 in Hela cells as positive controls [49]. Specific BRCA1 foci were observed in Hela cells, but only non-specific background when BRCA1 antibody was omitted (Fig. S4). At low magnification, BRCA1 immunofluorescence was visible in cytoplasm of oocytes. Young and middle-age ovaries contained many BRCA1 positive oocytes in primordial and primary follicles, in contrast to markedly reduced BRCA1 positive oocytes/follicles in old monkeys (Fig. 4a). Observations from immunofluorescence microscopy were confirmed by immunohistochemistry, showing BRCA1 as brownish staining from the DAB reaction in primary oocytes from primordial and primary follicles of young ovaries. BRCA immuno staining decreased dramatically in ovaries from old monkeys (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Immunocytochemistry and immunohistochemistry of DSB repair related gene BRCA1 in the ovaries of monkeys at various reproductive ages. a Representative images of immunofluorescence microscopy of DSB repair related gene BRCA1 examined at low magnification. Scale bar = 100 μm. b Immunohistochemistry of BRCA1 in monkey ovaries by DAB reaction. Sections of ovaries of monkeys at various reproductive ages were immunoreactively stained by BRCA1 antibody and exposed to DAB for the same short period of time. Sections without incubation with BRCA1 antibody did not show brownish staining following reaction with DAB and served as negative control. Scale bar = 50 μm. c BRCA1 immunofluorescence and average foci in the oocytes of primordial & primary follicles from ovaries from young (Y), middle-age (M) monkeys. The white broken circles indicate area of a GV nucleus. Scale bar = 10 μm. Error bars show mean + SEM. ***P < 0.001. n = number of GV nuclei counted

At higher magnification under immunofluorescence microscopy, BRCA1 stained the cytoplasm of oocytes from primordial and primary follicles in young and middle-age monkeys (Fig. 4c). BRCA1 immunostaining was not found in old monkeys. Moreover, more BRCA1 foci (>20) were found in the germinal vesicle (GV) of oocytes from young than from middle-age monkeys (Fig. 4c). Consistent with immunofluorescence microscopy, immunohistochemistry at higher magnification revealed that most oocytes in primordial and primary follicles from young and middle-age monkeys exhibited nuclear staining for BRCA1, whereas oocytes from old monkeys showed only weak or no staining for BRCA1. Similarly, young and middle-age monkeys showed BRCA1 nuclear staining in oocytes of secondary follicles, but old monkeys had only rare and weak BRCA1 nuclear staining (Fig. S5).

BRCA1 in granulosa cells decreases with monkey age

We also analyzed BRCA1 expression in granulosa cells. BRCA1 formed discrete foci in the nuclei of granulosa cells from primordial and primary follicles, although some cytoplasmic BRCA1 could be seen. BRCA1 foci were reduced from young, middle-age, to old monkeys (Fig. S6, S7A and B). Maternal age-associated decrease in expression of BRCA1 foci also was found in granulosa cells of secondary follicles, like that of primordial and primary follicles (Fig. S7C and D). Since antral follicles rarely could be found in old monkey ovaries, we only compared the BRCA1 expression in young and middle-age monkey ovaries. BRCA1 foci did not differ much in granulosa cells of antral follicles between young and middle-age monkey ovaries (Fig. S7E and F).

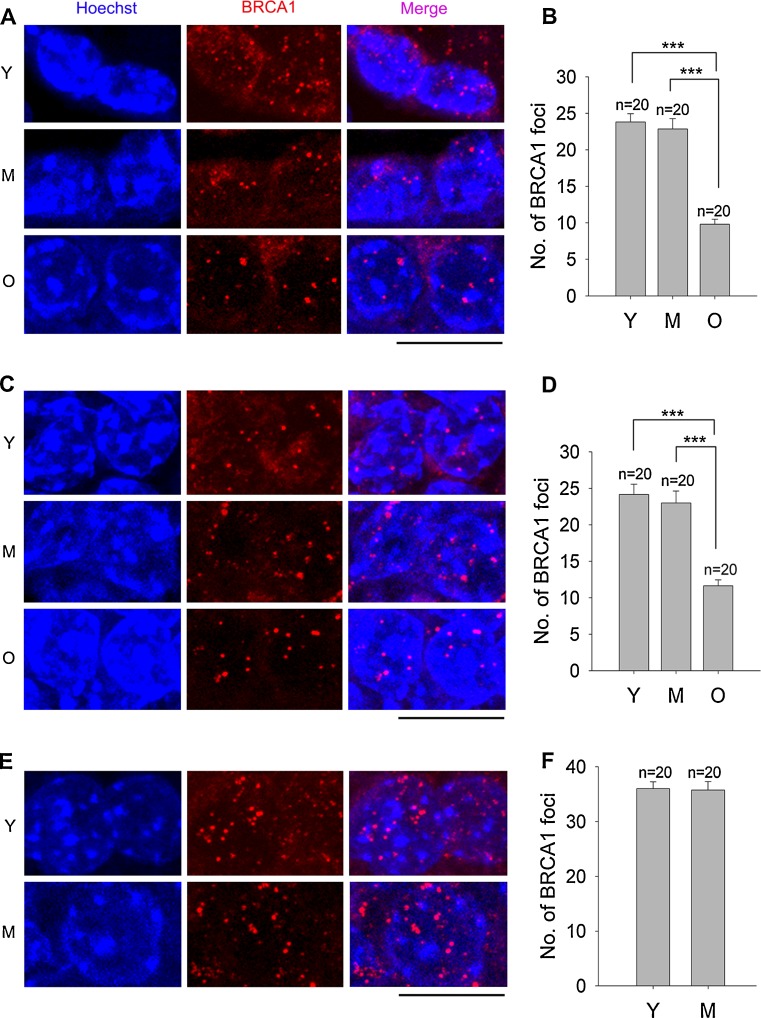

Epi-fluorescence microscropy only detected a few foci in images taken from each section, so we performed confocal microscopic analysis by three-dimensional reconstruction of the scanned images taken from the upper to the bottom of the section that is close to the whole nucleus. The trend for BRCA1 foci to decrease with the age as shown by confocal microscopy is consistent with that revealed by epi-fluorescence microscopy (Fig. S7), but confocal microscopy detects more BRCA1 foci (Fig. 5). Granulosa cells of primordial and primary follicles from young and middle-age monkeys showed a large number of BRCA1 foci (23.8 ± 1.2 and 22.9 ± 1.4, respectively). These foci were reduced in old monkeys (9.8 ± 0.7, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5a and b). BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells of secondary follicles also were reduced from young, middle-age (>20 foci) to old (<12 foci) monkeys (Fig. 5c and d). However, frequency of BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells did not differ much between young and middle-age monkey ovaries. Antral follicles also did not show difference in BRCA1 foci between young and middle-age monkeys (Fig. 5e and f). These data suggest significantly decreasing DNA repair function in granulosa cells of older monkey ovaries.

Fig. 5.

Confocal imaging analysis of BRCA1 foci in the granulosa cells of follicles from monkeys at various reproductive ages. a Confocal images by 3-D reconstruction of BRAC1 foci in granulosa cells of primordial & primary follicles in the ovaries from young (Y), middle-age (M) and old (O) monkeys. b Number of BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells of primordial & primary follicles. c 3-D reconstruction images of BRAC1 foci in granulosa cells of secondary follicles. d Number of BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells of secondary follicles. e, f 3-D reconstruction images and count of BRCA1 foci in granulosa cells of antral follicles of young and middle-age monkeys. Scale bar = 10 μm; Error bars show mean + SEM. ***P < 0.001. n = number of cells counted

Telomere length in monkey ovaries

We measured telomere length by qPCR in the monkey ovarian tissues. We were unable to isolate individual oocytes and granulosa cells to determine telomeres in specific cell types, due to the limited amount of live material. Telomeres shortened with advancing monkey age, although the difference did not reach statistical significance between old, young and middle age monkey ovaries (Fig. S8). This could be due to the small sample size- only three monkeys were used for each age group, the limited amount of tissue, variations among the individuals, and the mixed cell types.

Discussion

We show that DSBs and telomere damage in follicles increase with advancing age in monkeys, and that BRCA1 expression decreases in both oocytes and granulosa cells of primordial & primary, and secondary follicles. Increased DNA DSB damage is closely associated with reduced levels of DSB repair with monkey age, further supporting the findings in mice and humans that increased DNA damage and reduced DNA repair in oocytes is closely linked to ovarian aging [12]. We show that DSBs in granulosa cells increase with age.

Granulosa cells in primordial and primary follicles from young monkey ovaries display appreciable γH2AX foci, consistent with active DNA damage response. These foci increase with advancing age. γH2AX foci at telomeres, indicative of telomere dysfunction, are infrequent in granulosa cells of young and middle-age monkeys, but show limited yet significant increase with age. Although DSB foci increase in granulosa cells of primordial & primary, secondary and antral follicles in middle-age monkey ovaries, DSB repair BRCA1 foci seem not to decline with age. These data suggest that follicles and granulosa cells from middle age monkeys may still have high DSB repair capacity. Interestingly, a recent study shows that DNA strand breaks also accrue in human and murine hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) during aging and diminished DNA repair capacity may underlie this age-associated DNA damage accrual [50]. However, accumulated DNA damage during aging could be repaired upon entry into cell cycle and proliferation [50]. Flattened or cubic layer granulosa cells (the membrana granulosa) of primordial and primary follicles are positively stained for nuclear membrane Lamin A, but negative for proliferative markers PCNA or Ki67 [51–54], and the membrana granulosa cells are considered as differentiated cells, and these features also are consistent with their dormant state as follicle reservoir. On the contrary, many granulosa cells underneath the theca cells in the secondary growing and antral follicles show positive staining for PCNA or Ki67 but negative for Lamin A, and these granulosa cells exhibit stem cells-like property [6, 26]. High levels of BRCA1 expression in the proliferative stem-like cells could also help repair DSBs accumulated in the middle-age monkey ovaries.

Here we focused only on DSB and telomere damage mark γH2AX, and DSB repair protein BRCA1, although other proteins could also be altered with maternal age. In support, Brca1 knockout mice exhibit evident ovarian premature aging, and BRCA1 mutation reduces levels of AMH, reflecting decline in follicle reserve and ovarian function with maternal age [12]. BRCA1 mutations also are associated with occult primary ovarian insufficiency or defective meiosis and infertility [55–57]. Consistently, the number of dermal fibroblast nuclei containing DSB foci of 53BP1 or γH2AX and also TIFs increases exponentially with baboons’ age [58]. In the future, we plan to examine additional markers of DNA damage during ovarian aging.

It is likely that the age associated increase in DSBs are incompletely repaired because of the declining BRCA1 associated with ovarian aging. Extensive evidence shows that reactive oxidative stress induces DNA damage, reduces fertility [59] and contributes to telomere attrition [60]. Anti-oxidants reduce DNA damage and delay ovarian aging [45, 61], but it remains to be determined whether anti-oxidants delay ovarian aging in primate monkeys. Elevated DNA repair capacity from increased expression of BRCA1 in middle age might help repair telomeres and slow telomere shortening. Together, DNA DSB damage increases, and DSB repair function declines in granulosa cells with maternal age, as in oocytes. Decreased DSB repair could be slower than that of increased DNA damage. In corroboration with BRCA1 degradation with ovarian senescence in aging monkeys, BRCA1 germline mutations can lead to reduced ovarian reserve in humans [62]. While we recognize the limitations in the amount of monkey material available for this study, future studies of a larger scale should help clarify the role of DSB and BRCA1 expression in ovarian aging. Such research may help assess oocyte quality by measuring γH2AX and BRCA1 foci in oocytes or granulosa cells. Ultimately, approaches to reduce DNA damage and/or increase DNA repair pathways may help maintain follicle reserve and ovarian function with age.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 2818 kb)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MOST of China National Basic Research Program (2010CB94500), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31430052), and PCSIRT (No. IRT13023). The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule Increased DSBs and reduced DNA repair in granulosa cells may contribute to ovarian aging.

Contributor Information

David L. Keefe, Email: David.Keefe@nyumc.org

Lin Liu, Email: liutelom@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Faddy MJ. Follicle dynamics during ovarian ageing. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;163:43–8. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.te Velde ER, Scheffer GJ, Dorland M, Broekmans FJ, Fauser BC. Developmental and endocrine aspects of normal ovarian aging. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;145:67–73. doi: 10.1016/S0303-7207(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, Richardson SJ, Nelson JF. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1342–6. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Zheng W, Shen Y, Adhikari D, Ueno H, Liu K. Experimental evidence showing that no mitotically active female germline progenitors exist in postnatal mouse ovaries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12580–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206600109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lei L., Spradling A.C. Female mice lack adult germ-line stem cells but sustain oogenesis using stable primordial follicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013;110:8585–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yuan J, Zhang D, Wang L, Liu M, Mao J, Yin Y, et al. No evidence for neo-oogenesis may link to ovarian senescence in adult monkey. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2538–50. doi: 10.1002/stem.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Handel MA, Eppig JJ, Schimenti JC. Applying “gold standards” to in-vitro-derived germ cells. Cell. 2014;157:1257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashwood-Smith MJ, Edwards RG. DNA repair by oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 1996;2:46–51. doi: 10.1093/molehr/2.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guli CL, Smyth DR. Lack of effect of maternal age on UV-induced DNA repair in mouse oocytes. Mutat Res. 1989;210:323–8. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(89)90093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oktem O, Oktay K. A novel ovarian xenografting model to characterize the impact of chemotherapy agents on human primordial follicle reserve. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10159–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soleimani R, Heytens E, Darzynkiewicz Z, Oktay K. Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced human ovarian aging: double strand DNA breaks and microvascular compromise. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:782–93. doi: 10.18632/aging.100363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Titus S, Li F, Stobezki R, Akula K, Unsal E, Jeong K, et al. Impairment of BRCA1-related DNA double-strand break repair leads to ovarian aging in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:172ra121. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagaoka SI, Hassold TJ, Hunt PA. Human aneuploidy: mechanisms and new insights into an age-old problem. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:493–504. doi: 10.1038/nrg3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finch CE. The evolution of ovarian oocyte decline with aging and possible relationships to Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Exp Gerontol. 1994;29:299–304. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang ZB, Schatten H, Sun QY. Why is chromosome segregation error in oocytes increased with maternal aging? Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26:314–25. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00020.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh S, Feingold E, Chakraborty S, Dey SK. Telomere length is associated with types of chromosome 21 nondisjunction: a new insight into the maternal age effect on Down syndrome birth. Hum Genet. 2010;127:403–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-009-0785-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamada-Fukunaga T, Yamada M, Hamatani T, Chikazawa N, Ogawa S, Akutsu H, et al. Age-associated telomere shortening in mouse oocytes. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:108. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Franco S, Spyropoulos B, Moens PB, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Irregular telomeres impair meiotic synapsis and recombination in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6496–501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400755101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keefe DL, Liu L. Telomeres and reproductive aging. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:10–4. doi: 10.1071/RD08229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treff NR, Su J, Taylor D, Scott RT., Jr Telomere DNA deficiency is associated with development of human embryonic aneuploidy. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eppig JJ, Chesnel F, Hirao Y, O’Brien MJ, Pendola FL, Watanabe S, et al. Oocyte control of granulosa cell development: how and why. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:127–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su YQ, Sugiura K, Eppig JJ. Mouse oocyte control of granulosa cell development and function: paracrine regulation of cumulus cell metabolism. Semin Reprod Med. 2009;27:32–42. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1108008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Q, McKenzie LJ, Matzuk MM. Revisiting oocyte-somatic cell interactions: in search of novel intrafollicular predictors and regulators of oocyte developmental competence. Mol Hum Reprod. 2008;14:673–8. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gan064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatone C, Amicarelli F. The aging ovary–the poor granulosa cells. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:12–7. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng EH, Chen SU, Lee TH, Pai YP, Huang LS, Huang CC, et al. Evaluation of telomere length in cumulus cells as a potential biomarker of oocyte and embryo quality. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:929–36. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dzafic E, Stimpfel M, Virant-Klun I. Plasticity of granulosa cells: on the crossroad of stemness and transdifferentiation potential. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:1255–61. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayne S, Li H, Jones ME, Pinto AR, van Sinderen M, Drummond A, et al. Estrogen deficiency reversibly induces telomere shortening in mouse granulosa cells and ovarian aging in vivo. Protein Cell. 2011;2:333–46. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ozturk S, Sozen B, Demir N. Telomere length and telomerase activity during oocyte maturation and early embryo development in mammalian species. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:15–30. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gat055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blasco MA. Telomere length, stem cells and aging. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:640–9. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mermershtain I, Glover JN. Structural mechanisms underlying signaling in the cellular response to DNA double strand breaks. Mutat Res. 2013;750:15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caestecker KW, Van de Walle GR. The role of BRCA1 in DNA double-strand repair: past and present. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:575–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosen EM. BRCA1 in the DNA damage response and at telomeres. Front Genet. 2013;4:85. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robson M, Gilewski T, Haas B, Levin D, Borgen P, Rajan P, et al. BRCA-associated breast cancer in young women. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1642–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kauff ND, Satagopan JM, Robson ME, Scheuer L, Hensley M, Hudis CA, et al. Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1609–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rzepka-Gorska I, Tarnowski B, Chudecka-Glaz A, Gorski B, Zielinska D, Toloczko-Grabarek A. Premature menopause in patients with BRCA1 gene mutation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:59–63. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson J, Keefe DL. Ovarian aging: breaking up is hard to fix. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:172fs175. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez-Delgado B, Yanowsky K, Inglada-Perez L, de la Hoya M, Caldes T, Vega A, et al. Shorter telomere length is associated with increased ovarian cancer risk in both familial and sporadic cases. J Med Genet. 2012;49:341–4. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cabuy E, Newton C, Slijepcevic P. BRCA1 knock-down causes telomere dysfunction in mammary epithelial cells. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;122:336–42. doi: 10.1159/000167820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McPherson JP, Hande MP, Poonepalli A, Lemmers B, Zablocki E, Migon E, et al. A role for Brca1 in chromosome end maintenance. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:831–8. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Liu L, Montagna C, Ried T, Deng CX. Haploinsufficiency of Parp1 accelerates Brca1-associated centrosome amplification, telomere shortening, genetic instability, apoptosis, and embryonic lethality. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:924–31. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nichols SM, Bavister BD, Brenner CA, Didier PJ, Harrison RM, Kubisch HM. Ovarian senescence in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Hum Reprod. 2005;20:79–83. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilardi KV, Shideler SE, Valverde CR, Roberts JA, Lasley BL. Characterization of the onset of menopause in the rhesus macaque. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:335–40. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.2.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shideler SE, Gee NA, Chen J, Lasley BL. Estrogen and progesterone metabolites and follicle-stimulating hormone in the aged macaque female. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1718–25. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.6.1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu M, Yin Y, Ye X, Zeng M, Zhao Q, Keefe DL, et al. Resveratrol protects against age-associated infertility in mice. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:707–17. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cawthon RM. Telomere measurement by quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.10.e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowndes NF, Toh GW. DNA repair: the importance of phosphorylating histone H2AX. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R99–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takai H, Smogorzewska A, de Lange T. DNA damage foci at dysfunctional telomeres. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1549–56. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng L, Fong KW, Wang J, Wang W, Chen J. RIF1 counteracts BRCA1-mediated end resection during DNA repair. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:11135–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.457440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beerman I, Seita J, Inlay MA, Weissman IL, Rossi DJ. Quiescent hematopoietic stem cells accumulate DNA damage during aging that is repaired upon entry into cell cycle. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoop H, Honecker F, Cools M, de Krijger R, Bokemeyer C, Looijenga LH. Differentiation and development of human female germ cells during prenatal gonadogenesis: an immunohistochemical study. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1466–76. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Starborg M, Gell K, Brundell E, Hoog C. The murine Ki-67 cell proliferation antigen accumulates in the nucleolar and heterochromatic regions of interphase cells and at the periphery of the mitotic chromosomes in a process essential for cell cycle progression. J Cell Sci. 1996;109(Pt 1):143–53. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Funayama Y, Sasano H, Suzuki T, Tamura M, Fukaya T, Yajima A. Cell turnover in normal cycling human ovary. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:828–34. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.2.8636311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scalercio S.R., Brito A.B..., Domingues S.F., Santos R.R., Amorim C.A. Immunolocalization of growth, inhibitory, and proliferative factors involved in initial ovarian folliculogenesis from adult common squirrel monkey (Saimiri collinsi). Reprod Sci 2015;22:68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Oktay K, Kim JY, Barad D, Babayev SN. Association of BRCA1 mutations with occult primary ovarian insufficiency: a possible explanation for the link between infertility and breast/ovarian cancer risks. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:240–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leng M, Li G, Zhong L, Hou H, Yu D, Shi Q. Abnormal synapses and recombination in an azoospermic male carrier of a reciprocal translocation t(1;21) Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1293 e1217–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferguson KA, Chow V, Ma S. Silencing of unpaired meiotic chromosomes and altered recombination patterns in an azoospermic carrier of a t(8;13) reciprocal translocation. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:988–95. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herbig U, Ferreira M, Condel L, Carey D, Sedivy JM. Cellular senescence in aging primates. Science. 2006;311:1257. doi: 10.1126/science.1122446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Agarwal A, Gupta S, Sharma R. Oxidative stress and its implications in female infertility - a clinician’s perspective. Reprod BioMed Online. 2005;11:641–50. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)61174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Navarro P, Blasco MA, Keefe DL. Oxidative stress contributes to arsenic-induced telomere attrition, chromosome instability, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31998–2004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu J, Liu M, Ye X, Liu K, Huang J, Wang L, et al. Delay in oocyte aging in mice by the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1411–20. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang ET, Pisarska MD, Bresee C, Ida Chen YD, Lester J, Afshar Y, et al. BRCA1 germline mutations may be associated with reduced ovarian reserve. Fertil Steril. 2014;102:1723–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 2818 kb)