Abstract

We report on an 18-year-old man who had both acute monoblastic leukemia and Marfan syndrome. A diagnosis of Marfan syndrome was established by those characteristics of arachnodactyly, ectopia lentis, mitral valve prolapse, and mitral regurgitation. Findings on bone marrow examination of the patient showed that most of nucleated cells were monoblasts and immunophenotype of those cells showed CD13+, CD33+, CD56+, and HLA-DH+. To our knowledge, this is the second report of leukemia in Marfan syndrome in the world.

Key words: Marfan syndrome, Acute myelogenous leukemia

INTRODUCTION

The Marfan syndrome is a dominantly inherited disorder of connective tissue characterized by musculoskeletal, ocular, and cardiovascular abnormalities. The incidence of Marfan syndrome is estimated to be 1 in 10,000 in most racial and ethnic groups1).

Abnormal musculoskeletal findings include arachnodactyly, tall stature, scoliosis, pectus deformities, and ligamentous laxity. The cardiovascular complications of the disorder include mitral valve prolapse, mitral regurgitation, aortic valve insufficiency, and aortic dilatation, aneurysm, and dissection. The major ocular manifestations are lens dislocation and myopia2,3).

We have found one case report of acute leukemia in an infant with familial Marfan syndrome4). However, Acute leukemia in an adult with Marfan syndrome dose not appear to have been previously described. We report the only case of acute monoblastic leukemia with Marfan syndrome in an adult and this case is the second report of Marfan syndrome in the world.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old man was admitted to the Chonnam University Hospital because of general weakness for 4 weeks. His family had no medical problems. Nine years previously, he was admitted to the Department of Cardiac Surgery, and an echocardiographic examination showed mitral valve prolapse and moderate mitral regurgitation. Operation was recommended, but the patient refused and only received medical therapy.

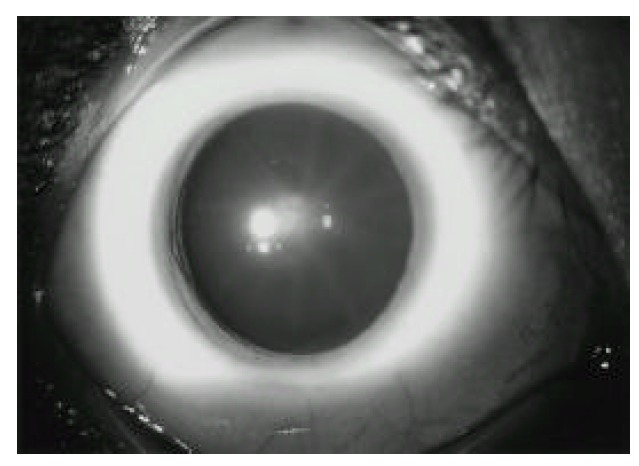

The blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg, the pulse was 112/min, the temperature was 37.4°C, and the respirations were 20/min. On examination, he appeared chronically ill. He was noted to have tall and thin stature with long tapered extremities and spider-like appearance of both hands. A grade III/VI holosystolic murmur was heard at the apex, with prominent radiation to the axilla. There were no palpable hepatosplenomegaly and lymph nodes. An ophthalmic examination by slit lamp showed lower lens zonular fibers due to mild upward displacement of lens in both eyes, that is, ecopia lentis, but he had adequate vision (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ophthalmic examination by slit lamp showing ectopia lentis in right eye.

The blood count showed a white cell count 107,700/mm3, hemoglobin 11.6g/dL, and platelet count 93,000/mm3. Blood chemistry revealed total serum protein 7.3g/dL, albumin 4.3g/dL, alkaline phosphatase 77U/L, AST 58U/L, ALT 15U/L, BUN 10.6mg/dL, Cr 0.9mg/dL, LDH 3317U/L and uric acid 7.6mg/dL. Coagulation profiles were PT 14.2sec (control 12.5sec), aPTT 35.3sec (control from 28 to 40sec) and fibrinogen assay 170mg/dL.

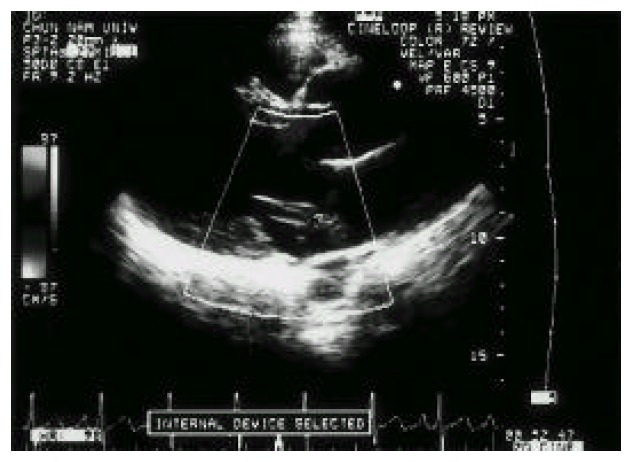

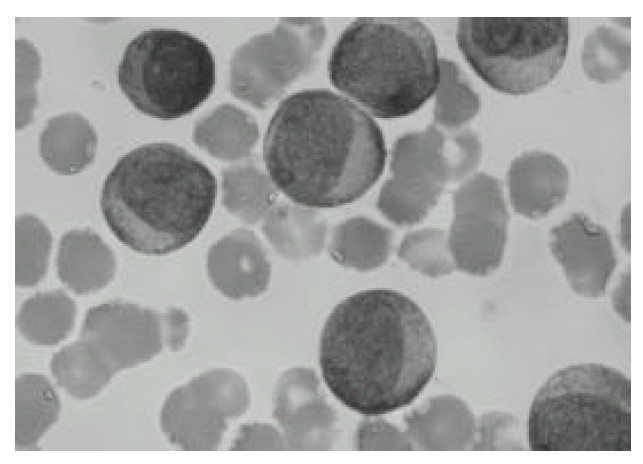

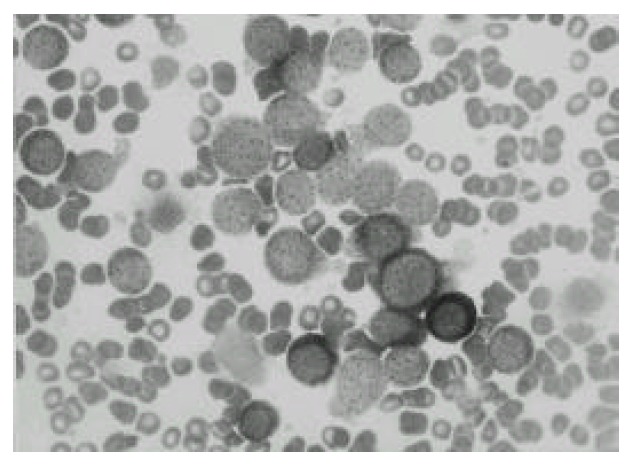

An electrocardiogram revealed no abnormalities except for a sinus tachycardia at a rate of 112. A radiograph of the chest was normal. Both hand AP roentgenogram showed arachnodactyly (Fig. 2). A radiograph of spine showed no scoliosis and kyphosis. An echocardiogram revealed the prolapse of posterior mitral leaflet and mitral regurgitation, but not aortic regurgitation and dissection (Fig. 3). Peripheral blood smear showed markedly increased blasts and decreased platelet count. Findings on bone marrow examination showed that most of the nucleated cells were monoblasts (Fig. 4a) that were negative on myeloperoxidase and chloracetate esterase staining but demonstrated positivity on staining with non-specific esterase (Fig. 4b). Immunophenotype of those cells showed CD13+, CD33+, CD56+ and HLA-DR+. Cytogenetic studies on the marrow showed 46 XY. He was diagnosed as acute monoblastic leukemia (M5a).

Fig. 3.

Echocardiogram (left parasternal long axis view) showing the prolapse of posterior mitral leaflet and mitral regurgitation.

Fig. 4a.

Bone marrow aspiration smear showing markedly increased blasts. (Wright stain, X1,000)

Fig. 4b.

Bone marrow aspiration smear reveals that most of leukemic cells are positive for NSE. (NSE stain, X400)

We recommended him to receive remission induction chemotherapy, but the patient gave up the therapy.

DISCUSSION

The diagnostic criteria for Marfan syndrome depend on the manifestations in the cardinal organ systems - the eye, the skeleton, the heart, and the aorta - and other systems and the family5). Neither excessive height nor lengthened arm span and longer segment can be relied on to confirm the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. The more specific manifestations for the Marfan syndrome are an aortic dilatation, aortic dissection in a nonhypertensive young person, ectopia lentis, and dural ectasia. Those manifestations are more important diagnostically than features common in other connective disorders. De Paepe et al6) proposed a revised diagnostic, criteria for Marfan syndrome and related conditions, including molecular analysis to the diagnosis.

Among patients with Marfan syndrome, cardiovascular abnormalities are the major source of morbidity and mortality7). The most common cardiovascular features are MVP and dilatation of the sinuses of Valsalva. Mitral valve prolapse develops early in life and about one-quarter progresses to mitral valve regurgitation8). Dissection of the ascending aorta is the leading cause of premature death9). The average life span of these patients is approximately 32 years. Thus, the effective treatment of patients with Marfan syndrome relies heavily on early and accurate diagnosis10).

In most cases, acute leukemia develops for unknown etiology. However, an increased risk of childhood leukemia has been associated with genetic syndromes including Down syndrome, Bloom syndrome, neurofibromatosis, Schwachman syndrome, ataxia telangiectasia and Klinefelter’s syndome11). Acute leukemia in familial Marfan syndrome was first reported in a child by Sharief et al4). Dexeus et al12) reported 2 cases of nonseminomatous testicular cancer and Marfan syndrome, and suggested the significance of genetic abnormalities. However, we have not been able to find any description of a relationship between leukemia and Marfan syndrome. Further genetic studies are warranted to know the association. Our case is the second report of Marfan syndrome associated with acute leukemia, but it is the only report in the world of an adult.

In summary, we report a case of Marfan syndrome associated with acute monoblastic leukemia in an adult.

REFERENCES

- 1.Braunwald E. Heart disease A textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 5th ed. Saunders; 1997. pp. 1669–1672. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pyeritz RE, McKusick VA. The Marfan syndrome: diagnosis and management. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:772–777. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197904053001406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett JC, Plum F. Cecil Textbook of medicine. 20th ed. Saunders; 1996. pp. 1119–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharief N, Kingston JE, Wright VM, Costeloe K. Acute leukemia in an infant with Marfan’s syndrome: a case report. Pediatric Hematol Oncol. 1991;8:323–327. doi: 10.3109/08880019109028805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beighton P, de Paepe A, Danks D, Finidori G, Gedde Dahl T, Goodman R, Hall JG, Hollister DW, Horton W, McKusick VA. International nosology of heritable disorders of connective tissue, Berlin, 1986. Am J Med Genet. 1988;29:581–594. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320290316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Paepe A, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Hennekam RC, Pyeritz RE. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:417–426. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960424)62:4<417::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murdoch JL, Walker BA, Kuzma JW, McKusick VA. Life expectancy and causes of death in the Marfan syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:804–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197204132861502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyeritz RE, Wappel MA. Mitral valve dysfunction in the Marfan syndrome: Clinical and echocardiographic study of prevalence and natural history. Am J Med. 1983;74:797–807. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman DI, Gray J, Roman MJ, Bridges A, Burton K, Boxer M, Devereux RB, Tsipouras P. Family history of severe cardiovascular disease in Marfan syndrome is associated with increased aortic diameter and decreased survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1062–1067. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverman DI, Burton KJ, Gray J, Bosner MS, Kouchoukos NT, Roman MJ, Boxer M, Devereux RB, Tsipouras P. Life expectancy in the Marfan syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)80066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler DP, Ross JA. Epidemiology of acute leukemia in children and adults. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dexeus FH, Logothetis CJ, Chong C, Sella A, Ogden S. Genetic abnormalities in men with germ cell tumors. J Urol. 1988;140:80–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]