Abstract

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) is the leading cause of transfusion-related morbidity and mortality world-wide. Although first described in 1983, it took two decades to develop consensus definitions that remain controversial. The pathogenesis of TRALI is related to the infusion of donor antibodies that recognize leukocyte antigens in the transfused host or the infusion of lipids and other biologic response modifiers that accumulate during storage or processing of blood components. TRALI appears to be the result of at least two sequential events and treatment is supportive. This review demonstrates that critically ill patients are more susceptible to TRALI and require special attention by critical care specialists, haematologists and transfusion medicine experts. Further research is required into TRALI and its pathogenesis so that transfusions are safer and administered appropriately. Avoidance including male-only transfusion practices, the use of leukoreduced components, fresher blood/blood components and solvent detergent plasma are also discussed.

Keywords: neutrophils, vascular endothelium, antibodies, lipid mediators, critically ill

Introduction

With the decrease of infectious transmission and bacterial contamination of transfused blood products, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) has become the leading cause of transfusion-related mortality reported by both the British Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) initiative and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA 2008) which has garnered the attention of the transfusion medicine community. Simultaneously, the critical care and trauma communities have published multiple articles showing an independent, dose dependent relationship between transfusion and the subsequent development of acute lung injury (ALI). Merging this literature, refining definitions and working together to educate clinicians and perform prospective trials in the area of TRALI is vital for future prevention. In this review we will synthesize these two bodies of literature and summarize the history, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of TRALI in the critically ill patient.

History

Non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema shortly following transfusion was first described in the 1950's (Barnard 1951, Brittingham 1957). In 1966 the first case series of TRALI described 3 patients who developed ALI during transfusion of whole blood (Philipps and Fleischner 1966). This clinical syndrome was given many different names including hypersensitivity pulmonary oedema, allergic pulmonary oedema, incompatibility of undetermined nature and an anaphylactoid reaction (Kernoff, et al 1972, Philipps and Fleischner 1966, Wolf and Canale 1976).

In 1983, Popovsky and colleagues described 5 cases of non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema after transfusion of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) or whole blood and gave the syndrome its current name, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). All five donors had leukoagglutinating and lymphocytotoxic antibodies in the serum and 3 of 5 recipients expressed the cognate antigens (Popovsky, et al 1983). This case series substantiated that a leukoagglutinating antibody may be etiologic in TRALI. This series also produced the first measure of TRALI incidence. These findings were confirmed in a series of 36 TRALI cases that included detailed clinical presentation data, prognosis, and incidence mechanistic studies that confirmed that antibodies could elicit TRALI (Popovsky and Moore 1985). Though coined in 1983, the consensus definitions of TRALI were published 2 decades later and remain controversial.

Definitions

In 2004, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute convened a working group to identify a common clinical definition to promote research in TRALI. The diagnosis must satisfy the criteria for ALI as summarized in Table 1 (Bernard, et al 1994). If an arterial blood gas is not available, oxygen saturations (SPO2) ≤ 90% are considered to meet the acute hypoxemia criterion when a patient is breathing room air at sea level. The use of oxygen saturation in the definition of TRALI is justified because an SPO2 ≤ 90% usually correlates with a PaO2 ≤ 60 mm Hg and therefore the PaO2/FiO2 ratio would be < 300 mm Hg (60/.21 = 286) (Toy, et al 2005).

Table I.

American-European Consensus definition of ALI (Bernard et al, 1994).

| Timing | Acute onset |

|---|---|

| Hypoxaemia | PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mm Hg regardless of PEEP |

| or | |

| If arterial blood gas unavailable SPO2 < 90% at sea level on room air | |

| Chest Radiograph | Bilateral infiltrates on frontal chest radiography |

| Permeability/Oedema | Pulmonary artery occlusion pressure ≤ 18 mm Hg |

| or | |

| No clinical evidence of left atrial hypertension |

ALI, acute lung injury, PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure.

In addition to meeting the standard criteria for ALI, TRALI requires additional criteria (Table 2). A patient must a) develop ALI during or within 6 hours of transfusion and b) no ALI may be present before transfusion. c) If alternative ALI risk factors exist (Table 3), TRALI can still be diagnosed if the clinical course of the patient suggests that ALI resulted mechanistically from the transfusion alone or a synergistic relationship between the transfusion and the underlying risk factor. If the temporal relationship between the transfusion and ALI (within 6 hours) is considered coincidental to the development of ALI from an alternate risk factor, a diagnosis of TRALI should not be used (Toy, et al 2005). Laboratory findings are not included as diagnostic criteria for TRALI; however, transient acute leucopoenia, leukocyte antigen-antibody match between donor and recipient (HLA class I or II, granulocytes or monocytes) or increased neutrophil priming activity in the plasma of blood products have been described (Toy, et al 2005). In contrast, the Canadian Consensus conference definition does not allow a diagnosis of TRALI to be made if other ALI risk factors exist, and “possible TRALI” is used for this patient subgroup (Kleinman, et al 2004).

Table II.

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Consensus Conference Definition of TRALI (Toy et al, 2005).

|

Helpful determinants (not required for diagnosis) for TRALI in patients with ALI include: transient leucopenia and antigen-antibody cross match between the donor and the recipient. (TR)ALI, (transfusion-related) acute lung injury.

Table III.

Risk factors for ALI in prospective studies (Fowler et al, 1983; Gong et al, 2005; Hudson et al, 1995; Pepe et al, 1982).

| ALI Risk Factor | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Septic shock | 47% |

| Pulmonary sepsis | Shock-35%, non-Shock-24% |

| Aspiration | 15–36% |

| Multiple Transfusions | 21–45% |

| Drug overdose in ICU | 9% |

| Long Bone Fracture | 5–11% |

| Pulmonary Contusion | 17–22% |

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass | 2% |

| Burn | 2% |

ALI, acute lung injury, ICU, intensive care unit.

In the ICU, 37-44% of patients receive blood products with the incidence rising to 85% in patients in the ICU ≥ 7 days (Corwin, et al 2004, Vincent, et al 2002). The incidence of TRALI in critically ill patients is estimated to be 8%, the transfusion incidence approaches 40%, and thus approximately 3% of all ICU admissions will develop TRALI, indicating that critically ill patients are the most vulnerable patient population (Gajic, et al 2007a). Because ALI is so common in intensive care units it is rarely recognized as TRALI despite multiple studies showing an independent, dose-dependent increase in ALI with transfused blood products when controlling for severity of illness and other known ALI risk factors (Chaiwat, et al 2009, Croce, et al 2005, Gajic, et al 2004, Gong, et al 2005, Khan, et al 2007, Silverboard, et al 2005, Zilberberg, et al 2007). In light of these studies and in response to the limitations of the consensus conference definition regarding timing of ALI in our critically ill patients, a 2008 review suggested expanding the definition of TRALI (Marik and Corwin 2008). The term delayed TRALI syndrome describes ALI that develops 6–72 hrs after transfusion regardless of the presence or absence of pre-existing ALI risk factors. Unlike the consensus definition, delayed TRALI syndrome occurs in up to 25% of critically ill patients receiving a blood transfusion, and is associated with a mortality approaching 40% (Marik and Corwin 2008). In addition, the risk of delayed TRALI syndrome rises with increasing numbers of transfused blood products (Marik and Corwin 2008). It is unclear whether similar pathophysiologic mechanisms apply, but an expanded clinical definition lays the groundwork for further clinical and mechanistic research in critically ill patients.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for patients who develop respiratory distress during or after transfusion include: TRALI, transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO), an anaphylactic transfusion reaction, and transfusion of contaminated (bacteria) blood products. Differentiating these four syndromes is often difficult due to similarities in their clinical presentation (table 4).

Table IV.

The Clinical and Laboratory Findings Associated with TRALI.

| Adverse Event | WBC | EP | Fever | Volume overload | Crackles on lung examination | Wheezing on lung examination | Pulmonary oedema on OCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRALI | ↓ | ↓ | Yes | No | Yes | Rare | Yes |

| TACO | ↔ | ↑ | No | Yes | Yes | Rare | Yes |

| Anaphylaxis | ↓ or ↑ | ↓ | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Sepsis | ↓ or ↑ | ↓ | Yes | No | Possible | No | Possible |

↑: increased, ↓: decreased, ↔: not affected.

TRALI, transfusion-related acute lung injury, TACO, transfusion associated circulatory overload; WBC, white blood cell count; BP, blood pressure; CXR, chest radiograph.

TRALI is the acute onset of severe dyspnea, tachypnea, worsening or new hypoxemia, fever, occasional hypotension and cyanosis that is temporally related to receiving transfused blood products (Popovsky and Moore 1985). This clinical presentation is clearly recognizable in non-critically ill patients with 72% eventually requiring mechanical ventilation. In contrast, in critically ill patients with other ALI risk factors such a presentation is common and therefore is rarely attributed to transfusion even when a clear temporal relationship exists. Differentiating TRALI (characterized by permeability oedema) from transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO) (characterized by hydrostatic oedema) is difficult in critically ill patients especially in the setting of massive transfusion and resuscitation. In the ICU, TACO has been reported to be three times more common than TRALI (Rana, et al 2006). Because pulmonary artery catheters lack clinical efficacy and are seldom used, hydrostatic oedema must be ruled out on clinical grounds. Potential laboratory tests differentiating TACO from TRALI include: 1) Undiluted oedema fluid obtained within 15 minutes of endotracheal intubation exhibiting an oedema fluid to plasma protein ratio of ≥ 0.6 suggests permeability oedema rather than hydrostatic pulmonary oedema (Ware and Matthay 2005); 2) The utility of the levels of B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-BNP (NT-pro-BNP) in differentiating TACO from TRALI is questionable though values at either extreme may aid in differentiating between these syndromes (Li, et al 2009, Tobian, et al 2008); 3) Transient neutropenia may support the diagnosis of TRALI due to neutrophil sequestration in the lung, but it is not universal (Nakagawa and Toy 2004).

Clinical factors differentiating TACO from TRALI include distended neck veins, S3 on cardiac exam and peripheral oedema consistent with volume overload. Acute onset hypertension suggests TACO while fever suggests TRALI (Skeate and Eastlund 2007). A chest radiograph with septal lines, cephalisation and an enlarged vascular pedicle (> 65mm) are more consistent with TACO. Rapid resolution of pulmonary oedema with the institution of diuretics also strongly suggests TACO while a leukocyte antibody-antigen cross match supports TRALI. Simple donor leukocyte antibody testing alone is unlikely to be clinically useful as 7-25% of donors are positive for leukocyte antibodies (Curtis and McFarland 2006).

Anaphylactic transfusion reactions usually present with bronchospasm resulting in tachypnea, wheezing, cyanosis, and severe hypotension. Facial and truncal erythema and oedema are also common with urticaria over the head, neck, and trunk (Silliman and McLaughlin 2006). The respiratory distress from anaphylactic transfusion reactions is related to laryngeal and bronchial oedema rather than pulmonary oedema so a chest radiograph will generally be clear. The transfusion of contaminated PRBCs or platelet concentrates may result in transfusion-related bacterial sepsis that manifests as fever, hypotension, and vascular collapse, and these patients may also experience ALI. Transfusion-related bacterial sepsis must be considered in transfused patients with pulmonary insufficiency and culturing the component bags is essential for diagnosis (Silliman and McLaughlin 2006).

Epidemiology

TRALI has been described with the infusion of most blood products including packed red blood cells (leukodepleted and non leukodepleted), fresh frozen plasma (multiparous and male donors), platelets (apheresed or random donor, whole blood-derived), and a few case reports of IVIG, cryoprecipitate, allogeneic bone marrow stem cells and transfused granulocytes (Reese, et al 1975, Rizk, et al 2001, Sachs and Bux 2003, Urahama, et al 2003).

The incidence of TRALI is variable and underreported

The reported incidence of TRALI is extremely variable. In addition, the incidence of TRALI for different blood products is dependent on the inflammatory state and characteristics of the patient population studied. The majority of incidence studies predate the acceptance of consensus definitions and therefore used a variety of diagnostic criteria to define TRALI. In addition, these studies utilized different methods of surveillance (passive surveillance vs. active case investigation vs. prospective data collection) that may impact the accuracy of the data due to reporting bias. Geographic regions have different blood banking practices which may also influence the incidence of TRALI. Retrospective “look-back” studies suggest that TRALI is grossly under-reported so the incidence reported in passive surveillance reports likely underestimates the true incidence, especially in the critically ill (Kleinman, et al 2004, Kopko, et al 2002).

TRALI is common in critically ill patients

The presence of multiple at risk diagnoses such as aspiration in conjunction with sepsis is associated with an increased susceptibility to develop ALI (table 3) (Fowler, et al 1983, Hudson, et al 1995, Pepe, et al 1982). Similarly, transfusion is an independent risk factor for the subsequent development of ALI in patients with pre-existing non-transfusion related ALI risk factors (Chaiwat, et al 2009, Croce, et al 2005, Gajic, et al 2004, Gong, et al 2005, Hudson, et al 1995, Silverboard, et al 2005). Incidence comparisons in these patient populations suggest that transfusion acts synergistically with other diagnoses that predispose patients to ALI. Furthermore, patients with established ALI have a dose dependent increase in mortality with each subsequent unit of transfused blood product (Gong, et al 2005). These observations were substantiated by a 2 year prospective study of consecutively transfused critically ill medical ICU patients that reported an overall TRALI incidence of 8%. The subgroup of patients with pre-existing ALI risk factors had the greatest risk of TRALI; moreover, an additional 11.6% of patients had worsening of their existing ALI after transfused blood products (Gajic, et al 2007a).

Critically ill patients have the highest incidence of TRALI suggesting that patient specific risk factors are very important in the pathogenesis. Because of under reporting, prospective observational studies that follow transfused patients for the subsequent development of TRALI are the best study design to determine the incidence. Unfortunately, prospective studies are lacking in most patient populations. The largest prospective trial to date enrolled 901 consecutively transfused medical intensive care unit patients over a two year period (Gajic, et al 2007a). 8% (74/901) of these patients developed TRALI resulting in an incidence of 1 in 12 patients as compared to the 1 in 625 patient incidence reported at the same institution two decades prior (Gajic, et al 2007a, Popovsky, et al 1983). This disparity is likely related to both underreporting which was avoided in the prospective trial and more importantly the patient population studied which was more vulnerable to TRALI. In this prospective trial, receipt of a transfusion with plasma rich blood products (FFP or platelets) was associated with the greatest risk of developing TRALI (Gajic, et al 2007a). Recently, a prospective trial of 225 patients admitted to an intensive care unit due to gastrointestinal bleeding revealed a TRALI incidence of 16.7% rising to 29% in patients with end stage liver disease (ESLD) (Benson 2009). This study confirms the extraordinary high incidence of TRALI in critically ill patients and suggests patients with ESLD may have a unique predisposition to this complication. In critically ill patients receiving massive transfusion the incidence of ALI is 21-45%, though these studies did not report the number of cases that were temporally-related to transfusion (within 6 hours) (Gong, et al 2005, Hudson, et al 1995, Pepe, et al 1982).

TRALI is more common with plasma-containing blood products

The recognized incidence rate for TRALI of 1/5,408 units or 1/625 patients transfused (all blood products) comes from the Mayo clinic (Popovsky, et al 1983, Popovsky and Moore 1985). In another single centre study, an overall TRALI incidence of 1/1,323 units was calculated (Silliman, et al 2003b). PRBCs had an incidence of 1/4,410 units while whole blood-derived platelet products and random donor platelet reactions were implicated ten times more often at 1 in 432 and 1 in 317 units respectively. In this same study the incidence of TRALI from FFP was 1/19,411 units, but has been reported at 1/7,900 units in a single centre in the United Kingdom (Wallis, et al 2003). In contrast to the Canadian single centre study where TRALI from FFP was less common than from red blood cells, in the UK study 10/11 cases of TRALI seen over a 12 year period were temporally and mechanistically attributed to FFP. A report from the Red Cross TRALI surveillance system implicates FFP as the etiologic agent in 75% of cases and 63% of deaths from TRALI (Eder, et al 2007). An examination of reported TRALI fatalities to the United States Food and Drug Administration between 1997-2002 implicated FFP in 50% of the 58 deaths reported (Holness, et al 2004).

In critically ill patients, epidemiologic studies reporting an association between massive transfusion and the development of ARDS failed to control for FFP which is universally administered as part of a massive transfusion protocol (Fowler, et al 1983, Hudson, et al 1995, Pepe, et al 1982). More recently, FFP administration has emerged as an independent risk factor for TRALI in both trauma, medical and surgical ICU populations (Chaiwat, et al 2009, Gajic, et al 2004, Gajic, et al 2007a, Gajic, et al 2007b, Khan, et al 2007, Sadis, et al 2007). In most of these studies, plasma containing blood products (FFP), not PRBCs, were associated with TRALI (Gajic, et al 2004, Gajic, et al 2007a, Khan, et al 2007, Rana, et al 2006, Sadis, et al 2007). Only recently have studies began to sort out the risk of ALI and TRALI (ALI within 6 hours) with the transfusion of plasma containing blood products as opposed to red blood cells in critically ill patients.

Transfusion increases mortality in patients with existing ALI

Mortality rates vary based on the patient population studied. In single centre studies TRALI-associated mortality was 6-13% (Popovsky and Haley 2000, Popovsky and Moore 1985). National reporting systems likely over-estimate the mortality rate in the general population due to reporting bias for cases resulting in death. Hemovigilance data from Great Britain (SHOT), Quebec, and France reported a TRALI mortality rate of 9%, 9.5% and 15%, respectively (Bux 2005, Rebibo, et al 2004). In critically ill patients requiring intensive care the TRALI mortality was 41% (Gajic, et al 2007a).

Pathophysiology

We refer the reader to two excellent reviews for details regarding TRALI pathogenesis. One was recently published in this journal (Bux and Sachs 2007) and the other was written by one of the authors of this review (Silliman and McLaughlin 2006) (Figure 1). In this review, we will give a brief overview of the current pathophysiologic understanding of TRALI and speculate on how epidemiologic observations in TRALI and transfusion associated ALI in critically ill patients may be described by our current mechanistic understanding.

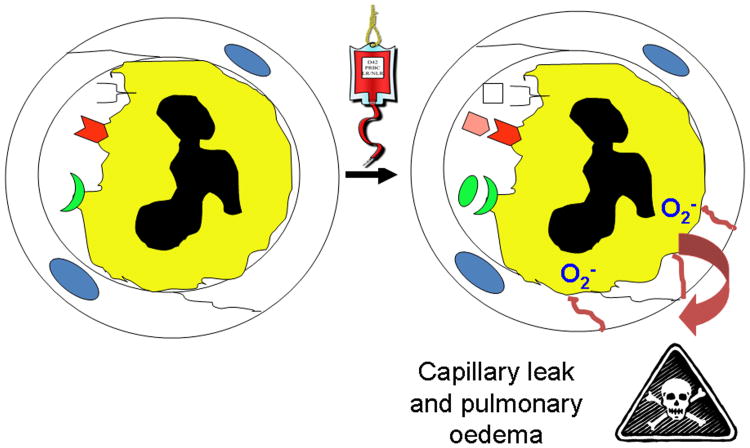

Figure 1. The pathophysiology of TRALI. Fig.1A Neutrophil-mediated TRALI.

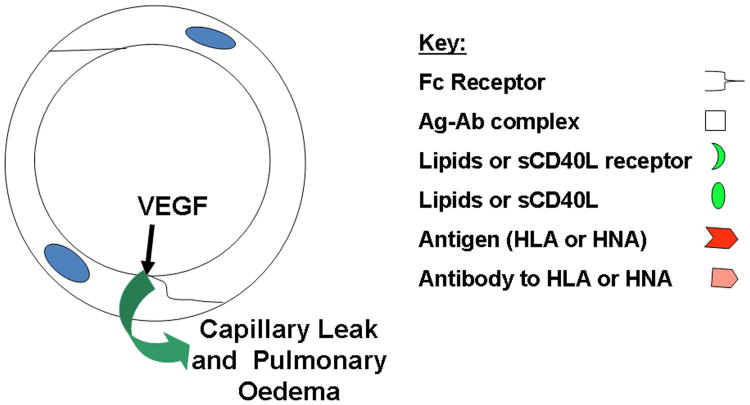

PMNs, which are sequestered by pro-inflammatory activation of the pulmonary microvascular endothelium, may be activated by the infusion of antibodies, which recognize the surface antigens expressed upon neutrophils, or biologically active lipids and/or sCD40L which activate distinct neutrophil receptors (Kelher, et al 2009, Khan, et al 2006). Antibodies, lipids, or sCD40L activate the microbicidal arsenal of the primed, sequestered neutrophils producing superoxide anion (O2-), which causes endothelial damage, capillary leak and ALI at the points of firm adhesion. Other causes of TRALI may present antigen antibody complexes on the surface of endothelium which are scavenged by the Fc receptors of neutrophils causing their activation and EC damage and ALI (Looney, et al 2006). Fig.1B TRALI in the absence of neutrophils. Lastly, permeability agents, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) could activate pulmonary endothelium resulting in a decrease in the size of the endothelial cells rendering the pulmonary capillaries leaky resulting in non-cardiogenic pulmonary oedema and ALI (Boshkov 2000).

The two-event model

Multiple animal studies and histological data from humans with TRALI support the following chain of events. First, the pulmonary vascular endothelium is activated (pro-inflammatory) resulting in priming (adherence) of neutrophils by one or more endogenous stimuli (i.e. sepsis, surgery), which are considered the “first event”. nd activation with endothelial cell activation is likely dependent on the particular mechanism involved (antibody-antigen complex vs. bioactive lipid activation vs. sepsis vs. other) but all pathways result in the same downstream event, neutrophilic lung injury (Bux and Sachs 2007, Sachs 2007, Silliman 2006). In the “two-event model” of TRALI the first hit likely represents a threshold effect where by more stimulus through similar or different mechanisms work through an additive or synergistic mechanism to bring neutrophils closer to subsequent activation and resulting lung injury (Bux and Sachs 2007, Silliman 2006). This is supported by the clinical observations that patients with different first hit ALI risk factors have very different risks of developing TRALI (Gajic, et al 2007a, Popovsky and Moore 1985). It is also likely that continued stimulus in the face of existing lung injury potentiates neutrophilic sequestration, invasion, and resulting pulmonary tissue damage leading to worse outcomes. Multiple animal studies show that when lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or TNFα are used to activate the pulmonary endothelium eliciting priming and sequestration of neutrophils, subsequent transfusion of biologic mediators in blood products activate neutrophils and lead to the development of TRALI (Silliman, et al 2003a, Silliman, et al 1998). All mediators implicated in TRALI, including lipids, other biologic response modifiers, and antibodies can be explained by the two-event mechanism (Bux and Sachs 2007, Silliman and McLaughlin 2006).

Epidemiologic support for a two-event mechanism in ALI and TRALI

Multiple disease processes causing systemic inflammation are capable of activating the vascular endothelium and inducing adherence of PMNs with subsequent neutrophil activation and ALI. A broad range of substances exist in blood products that are capable of priming or activating primed neutrophils directly. Priming substances found in blood products include antibodies to human neutrophil antigens, HLA type I and HLA type II antigens, bioactive lipids, and soluble CD40-ligand (sCD40L). Some antibody-antigen interactions can prime and activate neutrophils de novo through a variety of potential mechanisms, but more commonly a patient requires pre-primed neutrophils or activated endothelial cells that are subsequently activated by one or more of the above substances. The higher incidence of TRALI in intensive care unit patients 8% vs. 0.16% in a mixed population of hospitalized patients may be related to the observation that the neutrophils in these patients have a greater degree of priming and are closer to the threshold of activation as compared to other patient populations (Gajic, et al 2007a, Popovsky and Moore 1985). Alternatively these patients could have activated endothelium for similar reasons. Though antibodies are present in the majority of TRALI cases, they are also present in 17% of randomly selected donors (Middelburg, et al 2008). Probability calculations suggest and look back studies confirm that antibody-antigen interactions occur commonly in transfused patients who never develop TRALI supporting that a first hit from inflammatory stimuli makes the antibody-antigen interaction more likely to result in neutrophil activation and resulting lung injury. Look-back studies have shown that the majority of patients transfused with blood products that contain antibodies do not develop TRALI even if their leukocytes contain the cognate antigen (Kopko, et al 2002, Nicolle, et al 2004, Toy, et al 2004, Van Buren, et al 1990). In the original series of 36 patients, 89% had donor antibodies implicated, but 86% (31/36) of the cohort had an operation within 48 hours, a known neutrophil priming stimulus (Popovsky and Moore 1985, Silliman 2006). Of the 195 TRALI cases reported between 1996 and 2006 to the British SHOT hemovigilance scheme, 40.5% of these patients had surgery or sepsis as reported reasons for transfusion (Chapman, et al 2009). In a case comparison of 10 TRALI patients to 10 patients with urticarial or febrile transfusion reactions, neutrophil priming was found to be significantly greater in the pre-transfusion sera in TRALI patients. All of the TRALI patients had an antecedent first insult (sepsis, surgery, massive transfusion, cytokine administration) compared with only 2/10 in the non-TRALI transfusion reaction group (Silliman, et al 1997).

Leukoreduction and TRALI risk

Residual leukocytes contaminating stored packed red blood cells (PRBCs) can theoretically potentiate TRALI by increasing the amount of lipids and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6. IL-8, TNF-α) that accumulate during storage (Kristiansson, et al 1996, Silliman, et al 1997). These substances may act as a second hit when transfused into a patient with endothelial activation and/or primed neutrophils resulting in TRALI (Luk, et al 2003, Silliman, et al 1997, Silliman, et al 1998). Unfortunately, in vitro and in vivo data do not support a decrease neutrophil priming activity or TRALI risk with leukoreduction (Biffl, et al 2001, Silliman, et al 2003a). One retrospective study showed a significant difference in TRALI reports before and after leukoreduction (Yazer, et al 2004). Unfortunately, no benefit was shown in a large (n= 14,786) Canadian pre-leukoreduction vs. post-leukoreduction retrospective cohort study in the need for mechanical ventilation (10.1% vs. 9.6%, adjusted odds ratio 0.97, p=0.63) (Hebert, et al 2003). Because 72% of patients with TRALI require mechanical ventilation it is reasonable to conclude that the TRALI incidence was unchanged by leukoreduction in this study. Similarly, there was no decrease in the development of ALI with leukoreduction in a double blind randomized controlled trial performed in 268 injured patients requiring blood transfusion within 24 hours of injury (Watkins, et al 2008). Another randomized controlled trial of 2,780 patients revealed no benefit to leukoreduction with respect to hospital mortality, length of stay or any other secondary end point. However, the development of TRALI was not specifically reported in this study (Dzik, et al 2002). In summary, pre-storage leukoreduction may reduce the accumulation of some of the biologically active components associated with storage, but does not seem to significantly alter TRALI risk.

Age of blood and TRALI risk

Storage of RBCs results in a number of morphological and biochemical alterations known as the RBC storage lesion. During routine storage of cellular components, a mixture of neutrophil priming substances like lysophosphatidylcholines accumulate. These substances can prime and activate neutrophils, cause endothelial cell activation and alter permeability in the alveolar capillary membrane (Silliman, et al 2003a, Silliman, et al 1994, Silliman, et al 1996, Silliman, et al 1997). The use of fresher blood products has been postulated to decrease the deleterious effects from prolonged storage in high risk patients. For example, the use of PRBCs <14 days old and platelet concentrates <2 days may prevent the development of neutrophil priming activity in blood (Silliman, et al 1994, Silliman, et al 1996). Multiple epidemiologic studies have shown an association between increasing age of red blood cells and increased mortality in trauma, medical, and surgical ICU patients (Basran, et al 2006, Koch, et al 2008, Purdy, et al 1997, Zallen, et al 1999). Age of blood was shown to be an independent risk factor for mortality in trauma after the institution of leukoreduction (Weinberg, et al 2008a, Weinberg, et al 2008b). In critically ill and post-surgical patients, storage duration has also been associated with increased nosocomial infection risk (Koch, et al 2008, Leal-Noval, et al 2003, Vamvakas and Carven 1999). However, until the data from prospective clinical trials are available the effect of storage duration on TRALI risk and outcome is undefined.

Multiparity and TRALI risk

The majority of severe TRALI cases are associated with alloantibodies to leukocytes (Eder, et al 2007, Kopko, et al 2001, Lydaki, et al 2005, Popovsky and Haley 2000, Popovsky and Moore 1985, Win, et al 2007). Due to the increased incidence of antibodies in female donor plasma and the specificities of these common antibodies, it is feasible that as many as 1 in 25 units from female donors could cause an antibody-antigen reaction in a random recipient. The probability would obviously change depending on the parity of the donor. The frequency of antibodies in plasma-containing blood products increases in multiparous donors as a result of multiple exposures to paternal antigens from the fetus during pregnancy. A large prospective study of 8,171 volunteer blood donors in the United States revealed a 17.3% prevalence of HLA antibody presence in female donors. The prevalence increased with number of pregnancies: 1.7% (zero), 11.2% (one), 22.5% (two), 27.5% (three) and 32.2% (four or more) (Triulzi, et al 2009). These values are strikingly similar to prospective data collected in 332 platelet pheresis donors a decade ago (Densmore, et al 1999). In a separate study 39.7% of females reporting three or more pregnancies had antibodies to either HLA class I, HLA class II or granulocytes (Sachs, et al 2008). Therefore, multiparity is associated with an increase in antibodies in donated blood products.

Several studies have examined the clinical significance of multiparity on the risk of developing TRALI. The British SHOT initiative reported that from 1999-2005, there were 49 cases in which FFP or platelets from female donors were implicated in TRALI and the implementation of male-only, a surrogate for antibody negative, plasma transfusion strategies have decreased fatal TRALI although these antibody-mediated TRALI reactions were in the critically ill (Chapman, et al 2009). In a review of reported TRALI fatalities to the American Red Cross, female donors with leukocyte antibodies were identified in 75% of fatal TRALI cases involving FFP administration (Eder, et al 2007). The Dutch reported a significant decrease in TRALI a year after male-only plasma administration (Vlaar, et al 2008). Lastly, TRALI incidence decreased from 21% to 36% [CI 0.16-0.90], p=.04) at a single centre in patients undergoing repair of a ruptured abdominal aneurysm after removal of females from the donor pool (Wright, et al 2008).

The clinical effects of multiparous plasma in critically ill patients was also studied in a prospective, randomized, crossover trial (Palfi, et al 2001). Critically ill patients (n=105) judged to require at least 2 units of plasma, received a unit of plasma from a multiparous woman (≥ 3 live births) and, 4 hours later, a unit of control plasma, or vice versa. Transfusion of plasma from multiparous women was associated with significantly lower post transfusion oxygen saturation and higher TNFα-concentrations. Another retrospective case-control study of 3,567 critically ill patients compared oxygenation (PaO2/FiO2 ratio) change after receipt of male vs. female donor high volume plasma containing blood products. Groups were well matched for baseline characteristics and presence of other ALI risk factors. For females there was significant drop in Pao2/Fio2 ratio (-52 mm Hg), but similar to the previous study there was no increase in the development of TRALI (Gajic, et al 2007b, Palfi, et al 2001).

The United Kingdom started antibody-negative (male-only) plasma transfusion protocols in July, 2003, the Dutch in October, 2006, and many blood banks in the United States followed suit (Chapman, et al 2009), Eder, et al 2007, Vlaar, et al 2008). Though there is mechanistic plausibility and epidemiologic support to remove multiparous females from the donor pool for the creation of plasma containing blood products, there has not been a randomized controlled trial with appropriate outcome variables (TRALI, mortality) to support this practice. Leukoreduction offers similar mechanistic and epidemiologic rationale, but did not reduce TRALI incidence in prospective trials. In addition, eliminating multiparous female donors from the donor pool for plasma containing blood products (FFP and platelets) would result in the loss of approximately of 30% of donors with a larger loss of platelet donors (Densmore, et al 1999, Eder, et al 2007, Webert and Blajchman 2003). It is unclear how to balance the current data implicating multiparous donors in TRALI with the potential shortages in plasma containing blood products created by eliminating multiparous females or all females from the donor pool. Though many countries and blood banks have eliminated females from the plasma donor pool and shown differences in before and after TRALI incidence reports, a least one prospective randomized controlled trial is needed to justify this action before it becomes universal.

Management

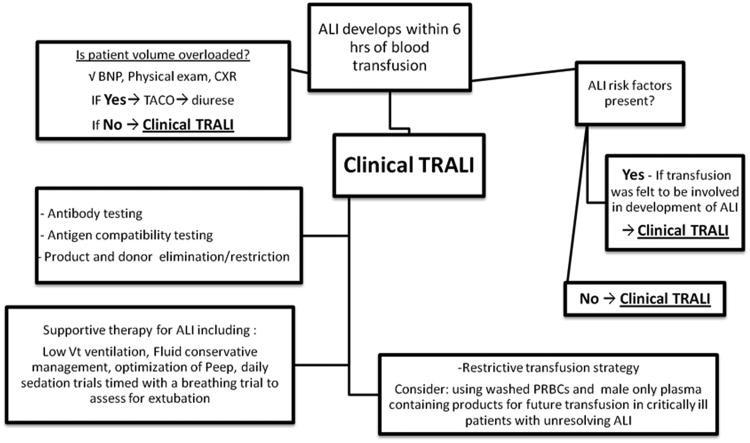

Figure 2 shows an algorithm for diagnosis and management of TRALI. When TRALI is diagnosed the management is similar to the management of ALI from other causes. This includes supportive care including optimization of mechanical ventilator parameters to avoid further injuring the lung while making sure the patient does not become intravascularly fluid overloaded (Wheeler and Bernard 2007). Daily awakenings from sedation timed with a breathing trial to assess for extubation decreases time on mechanical ventilation and improves outcomes (Girard, et al 2008). A restrictive transfusion strategy should be employed as transfusions in patients with existing ALI worsen outcome (Gong, et al 2005). In patients with unresolving TRALI or with other ALI risk factors (i.e. ongoing sepsis) consideration should be given to using washed PRBCs and male only plasma containing blood products for future transfusions with the rationale that removing all potential biologic mediators and antibodies may prevent further worsening of lung injury in these vulnerable hosts. It should be noted that this recommendation is not evidence based, but instead is based on good pathophysiologic rationale.

Figure 2. The Diagnosis and Management of TRALI.

In a patient who developed ALI within 6 hours of transfusion other aetiologies of pulmonary oedema must be ruled out especially volume overload (TACO). If there are other risk factors for ALI present then a clinical determination of the role of the transfusion must be determined and if transfusion is thought to be etiologic then the observed ALI is TRALI. Antigen antibody testing is completed to aid in confirmation and if positive than the donor is excluded from future plasma donations. If negative, then the observed TRALI is likely due to other agents including lipids or sCD40L and testing may be done in Denver of Brisbane, currently for these agents. Management of TRALI involves supportive care and ventilation with low tidal volumes (Vt). Further transfusions should be minimized, a restrictive transfusion policy, and washing of cellular blood products to remove antibodies and other biologic response modifiers should be considered.

Prevention and future directions

When a patient is diagnosed with TRALI, the donor and recipient's blood serum should be analyzed for a leukocyte antigen-antibody match. The recommendations from the 2008 International Society of Blood Transfusion meeting stress that HLA class I, HLA class II and human neutrophil antibody testing be done with established validated techniques (Bierling, et al 2009). In addition, HLA class I antibody detection should be restricted to antibodies clinically relevant for TRALI. When multiple blood products are implicated, this process can be time intensive and expensive. If a donor or donors are found to have leukocyte antibodies matching the recipient's antigens, most blood banks recall and discard current plasma containing blood products from the implicated donor and exclude future donation. Look-back studies of recipients of an implicated donor's blood product with known antibodies have revealed conflicting results, questioning whether donor elimination is warranted. In one study, 103 patients receiving plasma rich blood product from a donor with multiple common HLA antibodies were analyzed for TRALI (Toy, et al 2004). None of the patients developed TRALI even though 98% of the patients with known HLA types (54/55) had 1-5 corresponding HLA antigens. Other look back studies have shown TRALI risk to be higher in patients receiving plasma products from a donor with implicated antibodies, although a majority of the patients transfused did not develop TRALI (Kopko, et al 2002). Because 17% of randomly selected donors contain leukocyte antibodies, vigilant reporting or donor exclusion based on antibody testing may significantly decrease the plasma donor pool with unclear benefit (Bray, et al 2004, Middelburg, et al 2008). Considering the high incidence of TRALI in critically ill patients a vigilant reporting strategy would require a significant amount of resource utilization to test all implicated blood products and perform the necessary donor follow-up when an antibody-antigen cross match is confirmed (Kopko, et al 2002, Kram and Loer 2005, Wallis 2003).

The first step in preventing TRALI and other transfusion-related complications is education and enforcement of the appropriate use of blood products. In the critically ill, two randomized controlled trials have reported a decrease in the development of ALI by decreasing red blood cell transfusions. Furthermore, a prospective randomized controlled trial in non bleeding critically ill patients compared a restrictive transfusion strategy with target haemoglobin 7-9 g/dl to a more liberal transfusion strategy targeting haemoglobin of 10-12 g/dl. Patients in the restrictive group received less red cell transfusions (p<.01) resulting in a decrease in ALI (11.4% vs. 7.7%, p=.06) (Hebert, et al 1999). A prospective randomized controlled trial in blunt trauma compared the use of Factor VIIa vs. standard resuscitation and showed a decrease in red cell transfusions and a concomitant decrease in ALI (16% vs. 4%, p=.03) in the Factor VIIa group (Boffard, et al 2005). In critically ill patients, transfusion of red blood cells rarely improves oxygen utilization, plasma is often used outside of guideline recommendations, restrictive transfusion strategies improve outcomes, and these patients are at risk to develop TRALI. Physician education is required to adopt a restrictive transfusion policy in these patients.

Restricting FFP administration may have a potential larger benefit because FFP is used inappropriately in 45% of hospitalized patients and 47.6% of critically ill patients (Lauzier, et al 2007, Luk, et al 2002). Even guideline indicated use lacks level I evidence in many instances as there is evidence to suggest that FFP administration in bleeding patients with liver disease or before minor procedures to correct the INR is not beneficial (Dara, et al 2005, Holland and Sarode 2006, Lauzier, et al 2007, Tripodi 2009, Verghese 2008, Wallis and Dzik 2004). Prospective examination of FFP correction of mild coagulation abnormalities demonstrated that the international normalized ratio normalized in only 0.8% of the patients and decreased by at least 50% in only 15% of patients (Abdel-Wahab, et al 2006). FFP and other high plasma containing blood products (platelets) contain more antibodies than red cell products and are more commonly implicated in severe TRALI cases. Therefore, prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to examine different FFP transfusion strategies in critically ill patients.

Alternative strategies to reduce TRALI include washing cellular components to remove the biologically active mediators, including antibodies, associated with TRALI (Silliman and McLaughlin 2006). This strategy could be deployed for patients prior to major surgical procedures and those with a predicted need for ongoing blood transfusion (i.e. gastrointestinal bleeding, thermal injuries and septic shock). Unfortunately, washing cells a priori for use in emergent situations may reduce the product quality and shelf life of the blood product (Mair, et al 2006). Another alternative is solvent-detergent (S/D) treated plasma (Octaplas®) which dilutes or eliminates anti-leukocyte antibodies during the manufacturing process and to date neither antibodies to granulocyte-specific antigens nor to HLA class I and class II antigens were identified (Sachs, et al 2005, Sinnott, et al 2004). More than 13 million units of S/D FFP have been used and no cases of TRALI have been reported (Flesland 2007, Sachs 2007). Concern remains about the theoretic risk of infectious complications because SDP is made from the pooled plasma from thousands of donors and its efficacy compared to FFP has not been studied in a large, prospective clinical trial to substantiate its efficacy.

Conclusions

In summary, TRALI is a potentially fatal complication of blood transfusion. The mechanism is usually multifactorial due to both transfusion and patient specific risk factors. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that TRALI is very common (8%) in the intensive care unit because critically ill patients are more frequently transfused and often have activated endothelium and primed neutrophils (Gajic, et al 2007a). The critically ill are less frequently included in the TRALI literature because these patients often have other disease processes that can cause ALI in absence of transfusion. Due to a higher incidence of TRALI in critically ill patients, prospective randomized controlled trials in this patient population are feasible and can effectively evaluate current and novel transfusion strategies aimed at decreasing TRALI incidence. Because critically ill patients seem to have both an early and delayed TRALI syndrome, the transfusion and critical care communities should consider expanded definitions for critically ill patients (Marik and Corwin 2008). These different stages of TRALI could be validated with mechanistic studies that reveal different pathophysiological factors. Lastly, we need to increase awareness of the deleterious effects of TRALI throughout the critical care community. Currently, a restricted red blood cell transfusion approach is recommended in the ICU, but more dangerous plasma containing blood products like fresh frozen plasma are often used inappropriately (Lauzier, et al 2007). Philosophically, we should treat blood products like pharmaceuticals with continued refinement of the product in response to common and deadly side effects and perform large multicentre trials to show efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Alexander Benson and Marc Moss are supported through NIH grant K24 HLO89223. Christopher Silliman is supported by Bonfils Blood Center and grant GM49222 from NIGMS, NIH.

References

- Abdel-Wahab OI, Healy B, Dzik WH. Effect of fresh-frozen plasma transfusion on prothrombin time and bleeding in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities. Transfusion. 2006;46:1279–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard RD. Indiscriminate transfusion: a critique of case reports illustrating hypersensitivity reactions. N Y State J Med. 1951;51:2399–2402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basran S, Frumento RJ, Cohen A, Lee S, Du Y, Nishanian E, Kaplan HS, Stafford-Smith M, Bennett-Guerrero E. The association between duration of storage of transfused red blood cells and morbidity and mortality after reoperative cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:15–20. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000221167.58135.3d. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson AG, Silliman C, Moss M. Transfusion Associated Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) in Patients with Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Effect of End Stage Liver Disease and the Use of Fresh Frozen Plasma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A4639. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, Carlet J, Falke K, Hudson L, Lamy M, Legall JR, Morris A, Spragg R. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–824. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierling P, Bux J, Curtis B, Flesch B, Fung L, Lucas G, Macek M, Muniz-Diaz E, Porcelijn L, Reil A, Sachs U, Schuller R, Tsuno N, Uhrynowska M, Urbaniak S, Valentin N, Wikman A, Zupanska B. Recommendations of the ISBT Working Party on Granulocyte Immunobiology for leucocyte antibody screening in the investigation and prevention of antibody-mediated transfusion-related acute lung injury. Vox Sang. 2009;96:266–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2008.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, Ciesla DJ, Gonzalez RJ, Silliman CC. Plasma from aged stored red blood cells delays neutrophil apoptosis and primes for cytotoxicity: abrogation by poststorage washing but not prestorage leukoreduction. J Trauma. 2001;50:426–431. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00005. discussion 432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boffard KD, Riou B, Warren B, Choong PI, Rizoli S, Rossaint R, Axelsen M, Kluger Y. Recombinant factor VIIa as adjunctive therapy for bleeding control in severely injured trauma patients: two parallel randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trials. J Trauma. 2005;59:8–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171453.37949.b7. discussion 15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshkov LK, Maloney J, Bieber S, Silliman CC. Two cases of TRALI from the same platelet unit: implications for pathophysiology and the role of PMNs and VEGF. Blood. 2000;96:655a. [Google Scholar]

- Bray RA, Harris SB, Josephson CD, Hillyer CD, Gebel HM. Unappreciated risk factors for transplant patients: HLA antibodies in blood components. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:240–244. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittingham TE. Immunologic studies on leukocytes. Vox Sang. 1957;2:242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1957.tb03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bux J. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): a serious adverse event of blood transfusion. Vox Sang. 2005;89:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2005.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bux J, Sachs UJ. The pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) Br J Haematol. 2007;136:788–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiwat O, Lang JD, Vavilala MS, Wang J, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP. Early packed red blood cell transfusion and acute respiratory distress syndrome after trauma. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:351–360. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181948a97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CE, Stainsby D, Jones H, Love E, Massey E, Win N, Navarrete C, Lucas G, Soni N, Morgan C, Choo L, Cohen H, Williamson LM. Ten years of hemovigilance reports of transfusion-related acute lung injury in the United Kingdom and the impact of preferential use of male donor plasma. Transfusion. 2009;49:440–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin HL, Gettinger A, Pearl RG, Fink MP, Levy MM, Abraham E, MacIntyre NR, Shabot MM, Duh MS, Shapiro MJ. The CRIT Study: Anemia and blood transfusion in the critically ill--current clinical practice in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:39–52. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104112.34142.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce MA, Tolley EA, Claridge JA, Fabian TC. Transfusions result in pulmonary morbidity and death after a moderate degree of injury. J Trauma. 2005;59:19–23. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000171459.21450.dc. discussion 23-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis BR, McFarland JG. Mechanisms of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): anti-leukocyte antibodies. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S118–123. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214293.72918.D8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dara SI, Rana R, Afessa B, Moore SB, Gajic O. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in critically ill medical patients with coagulopathy. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2667–2671. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000186745.53059.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Densmore TL, Goodnough LT, Ali S, Dynis M, Chaplin H. Prevalence of HLA sensitization in female apheresis donors. Transfusion. 1999;39:103–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39199116901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzik WH, Anderson JK, O'Neill EM, Assmann SF, Kalish LA, Stowell CP. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of universal WBC reduction. Transfusion. 2002;42:1114–1122. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2002.00182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder AF, Herron R, Strupp A, Dy B, Notari EP, Chambers LA, Dodd RY, Benjamin RJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury surveillance (2003-2005) and the potential impact of the selective use of plasma from male donors in the American Red Cross. Transfusion. 2007;47:599–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA, C.f.B.E.a.R. Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion: Fiscal report 2008. Vol. 2009. US Food and Drug adminsitration; Rockville, Maryland: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flesland O. A comparison of complication rates based on published haemovigilance data. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33 Suppl 1:S17–21. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-2875-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler AA, Hamman RF, Good JT, Benson KN, Baird M, Eberle DJ, Petty TL, Hyers TM. Adult respiratory distress syndrome: risk with common predispositions. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:593–597. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajic O, Rana R, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, Lymp JF, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB. Acute lung injury after blood transfusion in mechanically ventilated patients. Transfusion. 2004;44:1468–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajic O, Rana R, Winters JL, Yilmaz M, Mendez JL, Rickman OB, O'Byrne MM, Evenson LK, Malinchoc M, DeGoey SR, Afessa B, Hubmayr RD, Moore SB. Transfusion-related acute lung injury in the critically ill: prospective nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007a;176:886–891. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200702-271OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajic O, Yilmaz M, Iscimen R, Kor DJ, Winters JL, Moore SB, Afessa B. Transfusion from male-only versus female donors in critically ill recipients of high plasma volume components. Crit Care Med. 2007b;35:1645–1648. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269036.16398.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard TD, Kress JP, Fuchs BD, Thomason JW, Schweickert WD, Pun BT, Taichman DB, Dunn JG, Pohlman AS, Kinniry PA, Jackson JC, Canonico AE, Light RW, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Gordon SM, Hall JB, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW. Efficacy and safety of a paired sedation and ventilator weaning protocol for mechanically ventilated patients in intensive care (Awakening and Breathing Controlled trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371:126–134. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong MN, Thompson BT, Williams P, Pothier L, Boyce PD, Christiani DC. Clinical predictors of and mortality in acute respiratory distress syndrome: potential role of red cell transfusion. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1191–1198. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165566.82925.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PC, Fergusson D, Blajchman MA, Wells GA, Kmetic A, Coyle D, Heddle N, Germain M, Goldman M, Toye B, Schweitzer I, vanWalraven C, Devine D, Sher GD. Clinical outcomes following institution of the Canadian universal leukoreduction program for red blood cell transfusions. Jama. 2003;289:1941–1949. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.15.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, Marshall J, Martin C, Pagliarello G, Tweeddale M, Schweitzer I, Yetisir E. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland L, Sarode R. Should plasma be transfused prophylactically before invasive procedures? Curr Opin Hematol. 2006;13:447–451. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000245688.47333.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holness L, Knippen MA, Simmons L, Lachenbruch PA. Fatalities caused by TRALI. Transfus Med Rev. 2004;18:184–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson LD, Milberg JA, Anardi D, Maunder RJ. Clinical risks for development of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:293–301. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.2.7842182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelher MR, Masuno T, Moore EE, Damle S, Meng X, Song Y, Liang X, Niedzinski J, Geier SS, Khan SY, Gamboni-Robertson F, Silliman CC. Plasma from stored packed red blood cells and MHC class I antibodies causes acute lung injury in a 2-event in vivo rat model. Blood. 2009;113:2079–2087. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-177857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernoff PB, Durrant IJ, Rizza CR, Wright FW. Severe allergic pulmonary oedema after plasma transfusion. Br J Haematol. 1972;23:777–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1972.tb03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan H, Belsher J, Yilmaz M, Afessa B, Winters JL, Moore SB, Hubmayr RD, Gajic O. Fresh-frozen plasma and platelet transfusions are associated with development of acute lung injury in critically ill medical patients. Chest. 2007;131:1308–1314. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SY, Kelher MR, Heal JM, Blumberg N, Boshkov LK, Phipps R, Gettings KF, McLaughlin NJ, Silliman CC. Soluble CD40 ligand accumulates in stored blood components, primes neutrophils through CD40, and is a potential cofactor in the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood. 2006;108:2455–2462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-017251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman S, Caulfield T, Chan P, Davenport R, McFarland J, McPhedran S, Meade M, Morrison D, Pinsent T, Robillard P, Slinger P. Toward an understanding of transfusion-related acute lung injury: statement of a consensus panel. Transfusion. 2004;44:1774–1789. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch CG, Li L, Sessler DI, Figueroa P, Hoeltge GA, Mihaljevic T, Blackstone EH. Duration of red-cell storage and complications after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1229–1239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopko PM, Marshall CS, MacKenzie MR, Holland PV, Popovsky MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: report of a clinical look-back investigation. Jama. 2002;287:1968–1971. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.15.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopko PM, Popovsky MA, MacKenzie MR, Paglieroni TG, Muto KN, Holland PV. HLA class II antibodies in transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 2001;41:1244–1248. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41101244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kram R, Loer SA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: lack of recognition because of unawareness of this complication? Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005;22:369–372. doi: 10.1017/s0265021505000633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansson M, Soop M, Saraste L, Sundqvist KG. Cytokines in stored red blood cell concentrates: promoters of systemic inflammation and simulators of acute transfusion reactions? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996;40:496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzier F, Cook D, Griffith L, Upton J, Crowther M. Fresh frozen plasma transfusion in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1655–1659. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269370.59214.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Noval SR, Jara-Lopez I, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Marin-Niebla A, Herruzo-Aviles A, Camacho-Larana P, Loscertales J. Influence of erythrocyte concentrate storage time on postsurgical morbidity in cardiac surgery patients. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:815–822. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Daniels CE, Kojicic M, Krpata T, Wilson GA, Winters JL, Moore SB, Gajic O. The accuracy of natriuretic peptides (brain natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic) in the differentiation between transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-related circulatory overload in the critically ill. Transfusion. 2009;49:13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looney MR, Su X, Van Ziffle JA, Lowell CA, Matthay MA. Neutrophils and their Fc gamma receptors are essential in a mouse model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1615–1623. doi: 10.1172/JCI27238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk C, Eckert KM, Barr RM, Chin-Yee IH. Prospective audit of the use of fresh-frozen plasma, based on Canadian Medical Association transfusion guidelines. Cmaj. 2002;166:1539–1540. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk CS, Gray-Statchuk LA, Cepinkas G, Chin-Yee IH. WBC reduction reduces storage-associated RBC adhesion to human vascular endothelial cells under conditions of continuous flow in vitro. Transfusion. 2003;43:151–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydaki E, Bolonaki E, Nikoloudi E, Chalkiadakis E, Iniotaki-Theodoraki A. HLA class II antibodies in transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI). A case report. Transfus Apher Sci. 2005;33:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair DC, Hirschler N, Eastlund T. Blood donor and component management strategies to prevent transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S137–143. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214291.93884.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik PE, Corwin HL. Acute lung injury following blood transfusion: expanding the definition. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3080–3084. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818c3801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelburg RA, van Stein D, Briet E, van der Bom JG. The role of donor antibodies in the pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury: a systematic review. Transfusion. 2008;48:2167–2176. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa M, Toy P. Acute and transient decrease in neutrophil count in transfusion-related acute lung injury: cases at one hospital. Transfusion. 2004;44:1689–1694. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolle AL, Chapman CE, Carter V, Wallis JP. Transfusion-related acute lung injury caused by two donors with anti-human leucocyte antigen class II antibodies: a look-back investigation. Transfus Med. 2004;14:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.0958-7578.2004.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfi M, Berg S, Ernerudh J, Berlin G. A randomized controlled trial of transfusion-related acute lung injury: is plasma from multiparous blood donors dangerous? Transfusion. 2001;41:317–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41030317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe PE, Potkin RT, Reus DH, Hudson LD, Carrico CJ. Clinical predictors of the adult respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Surg. 1982;144:124–130. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipps E, Fleischner FG. Pulomonary edema in the course of a blood transfusion without overloading the circulation. Dis Chest. 1966;50:619–623. doi: 10.1378/chest.50.6.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovsky MA, Abel MD, Moore SB. Transfusion-related acute lung injury associated with passive transfer of antileukocyte antibodies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:185–189. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovsky MA, Haley NR. Further characterization of transfusion-related acute lung injury: demographics, clinical and laboratory features, and morbidity. Immunohematology. 2000;16:157–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovsky MA, Moore SB. Diagnostic and pathogenetic considerations in transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 1985;25:573–577. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25686071434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy FR, Tweeddale MG, Merrick PM. Association of mortality with age of blood transfused in septic ICU patients. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1256–1261. doi: 10.1007/BF03012772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R, Fernandez-Perez ER, Khan SA, Rana S, Winters JL, Lesnick TG, Moore SB, Gajic O. Transfusion-related acute lung injury and pulmonary edema in critically ill patients: a retrospective study. Transfusion. 2006;46:1478–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebibo D, Hauser L, Slimani A, Herve P, Andreu G. The French Haemovigilance System: organization and results for 2003. Transfus Apher Sci. 2004;31:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese EP, Jr, McCullough JJ, Craddock PR. An adverse pulmonary reaction to cryoprecipitate in a hemophiliac. Transfusion. 1975;15:583–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1975.15676082234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizk A, Gorson KC, Kenney L, Weinstein R. Transfusion-related acute lung injury after the infusion of IVIG. Transfusion. 2001;41:264–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41020264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs UJ. The pathogenesis of transfusion-related acute lung injury and how to avoid this serious adverse reaction of transfusion. Transfus Apher Sci. 2007;37:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs UJ, Bux J. TRALI after the transfusion of cross-match-positive granulocytes. Transfusion. 2003;43:1683–1686. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2003.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs UJ, Kauschat D, Bein G. White blood cell-reactive antibodies are undetectable in solvent/detergent plasma. Transfusion. 2005;45:1628–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs UJ, Link E, Hofmann C, Wasel W, Bein G. Screening of multiparous women to avoid transfusion-related acute lung injury: a single centre experience. Transfus Med. 2008;18:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3148.2008.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadis C, Dubois MJ, Melot C, Lambermont M, Vincent JL. Are multiple blood transfusions really a cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome? Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2007;24:355–361. doi: 10.1017/S0265021506001608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC. The two-event model of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S124–131. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000214292.62276.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Bjornsen AJ, Wyman TH, Kelher M, Allard J, Bieber S, Voelkel NF. Plasma and lipids from stored platelets cause acute lung injury in an animal model. Transfusion. 2003a;43:633–640. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Boshkov LK, Mehdizadehkashi Z, Elzi DJ, Dickey WO, Podlosky L, Clarke G, Ambruso DR. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: epidemiology and a prospective analysis of etiologic factors. Blood. 2003b;101:454–462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Clay KL, Thurman GW, Johnson CA, Ambruso DR. Partial characterization of lipids that develop during the routine storage of blood and prime the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;124:684–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Dickey WO, Paterson AJ, Thurman GW, Clay KL, Johnson CA, Ambruso DR. Analysis of the priming activity of lipids generated during routine storage of platelet concentrates. Transfusion. 1996;36:133–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36296181925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, McLaughlin NJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood Rev. 2006;20:139–159. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Paterson AJ, Dickey WO, Stroneck DF, Popovsky MA, Caldwell SA, Ambruso DR. The association of biologically active lipids with the development of transfusion-related acute lung injury: a retrospective study. Transfusion. 1997;37:719–726. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37797369448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman CC, Voelkel NF, Allard JD, Elzi DJ, Tuder RM, Johnson JL, Ambruso DR. Plasma and lipids from stored packed red blood cells cause acute lung injury in an animal model. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1458–1467. doi: 10.1172/JCI1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverboard H, Aisiku I, Martin GS, Adams M, Rozycki G, Moss M. The role of acute blood transfusion in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with severe trauma. J Trauma. 2005;59:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnott P, Bodger S, Gupta A, Brophy M. Presence of HLA antibodies in single-donor-derived fresh frozen plasma compared with pooled, solvent detergent-treated plasma (Octaplas) Eur J Immunogenet. 2004;31:271–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.2004.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeate RC, Eastlund T. Distinguishing between transfusion related acute lung injury and transfusion associated circulatory overload. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:682–687. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282ef195a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobian AA, Sokoll LJ, Tisch DJ, Ness PM, Shan H. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is a useful diagnostic marker for transfusion-associated circulatory overload. Transfusion. 2008;48:1143–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy P, Hollis-Perry KM, Jun J, Nakagawa M. Recipients of blood from a donor with multiple HLA antibodies: a lookback study of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 2004;44:1683–1688. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.04193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toy P, Popovsky MA, Abraham E, Ambruso DR, Holness LG, Kopko PM, McFarland JG, Nathens AB, Silliman CC, Stroncek D. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: definition and review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:721–726. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000159849.94750.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi A. Tests of coagulation in liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triulzi DJ, Kleinman S, Kakaiya RM, Busch MP, Norris PJ, Steele WR, Glynn SA, Hillyer CD, Carey P, Gottschall JL, Murphy EL, Rios JA, Ness PM, Wright DJ, Carrick D, Schreiber GB. The effect of previous pregnancy and transfusion on HLA alloimmunization in blood donors: implications for a transfusion-related acute lung injury risk reduction strategy. Transfusion. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urahama N, Tanosaki R, Masahiro K, Iijima K, Chizuka A, Kim SW, Hori A, Kojima R, Imataki O, Makimito A, Mineishi S, Takaue Y. TRALI after the infusion of marrow cells in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Transfusion. 2003;43:1553–1557. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vamvakas EC, Carven JH. Transfusion and postoperative pneumonia in coronary artery bypass graft surgery: effect of the length of storage of transfused red cells. Transfusion. 1999;39:701–710. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39070701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buren NL, Stroncek DF, Clay ME, McCullough J, Dalmasso AP. Transfusion-related acute lung injury caused by an NB2 granulocyte-specific antibody in a patient with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfusion. 1990;30:42–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1990.30190117629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verghese SG. Elective fresh frozen plasma in the critically ill: what is the evidence? Crit Care Resusc. 2008;10:264–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, Gattinoni L, Thijs L, Webb A, Meier-Hellmann A, Nollet G, Peres-Bota D. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. Jama. 2002;288:1499–1507. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.12.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaar AP, Binnekade JM, Schultz MJ, Juffermans NP, Koopman MM. Preventing TRALI: ladies first, what follows? Crit Care Med. 2008;36:3283–3284. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31818f2f37. author reply 3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JP. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI)--under-diagnosed and under-reported. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:573–576. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JP, Dzik S. Is fresh frozen plasma overtransfused in the United States? Transfusion. 2004;44:1674–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.0041-1132.2004.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis JP, Lubenko A, Wells AW, Chapman CE. Single hospital experience of TRALI. Transfusion. 2003;43:1053–1059. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2003.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware LB, Matthay MA. Clinical practice. Acute pulmonary edema. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2788–2796. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp052699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins TR, Rubenfeld GD, Martin TR, Nester TA, Caldwell E, Billgren J, Ruzinski J, Nathens AB. Effects of leukoreduced blood on acute lung injury after trauma: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1493–1499. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318170a9ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webert KE, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfus Med Rev. 2003;17:252–262. doi: 10.1016/s0887-7963(03)00039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Griffin RL, Huynh VQ, Cherry SA, 3rd, Marques MB, Reiff DA, Kerby JD, Rue LW., 3rd Age of transfused blood: an independent predictor of mortality despite universal leukoreduction. J Trauma. 2008a;65:279–282. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31817c9687. discussion 282-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg JA, McGwin G, Jr, Marques MB, Cherry SA, 3rd, Reiff DA, Kerby JD, Rue LW., 3rd Transfusions in the less severely injured: does age of transfused blood affect outcomes? J Trauma. 2008b;65:794–798. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318184aa11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical review. Lancet. 2007;369:1553–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win N, Massey E, Lucas G, Sage D, Brown C, Green A, Contreras M, Navarrete C. Ninety-six suspected transfusion related acute lung injury cases: investigation findings and clinical outcome. Hematology. 2007;12:461–469. doi: 10.1080/10245330701562345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf CF, Canale VC. Fatal pulmonary hypersensitivity reaction to HL-A incompatible blood transfusion: report of a case and review of the literature. Transfusion. 1976;16:135–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1976.16276155107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SE, Snowden CP, Athey SC, Leaver AA, Clarkson JM, Chapman CE, Roberts DR, Wallis JP. Acute lung injury after ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: the effect of excluding donations from females from the production of fresh frozen plasma. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1796–1802. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181743c6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazer MH, Podlosky L, Clarke G, Nahirniak SM. The effect of prestorage WBC reduction on the rates of febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions to platelet concentrates and RBC. Transfusion. 2004;44:10–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0041-1132.2003.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen G, Offner PJ, Moore EE, Blackwell J, Ciesla DJ, Gabriel J, Denny C, Silliman CC. Age of transfused blood is an independent risk factor for postinjury multiple organ failure. Am J Surg. 1999;178:570–572. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberberg MD, Carter C, Lefebvre P, Raut M, Vekeman F, Duh MS, Shorr AF. Red blood cell transfusions and the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome among the critically ill: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2007;11:R63. doi: 10.1186/cc5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]