Abstract

Aims

Most brain diseases are complex entities. Although animal models or cell culture experiments mimic some disease aspects, human post mortem brain tissue remains essential to advance our understanding of brain diseases using biochemical and molecular techniques. Post mortem artefacts must be properly understood, standardized, and either eliminated or factored into such experiments. Here we examine the influence of several premortem and post mortem factors on pH, and discuss the role of pH as a biochemical marker for brain tissue quality.

Methods

We assessed brain tissue pH in 339 samples from 116 brains provided by 8 different European and 2 Australian brain bank centres. We correlated brain pH with tissue source, post mortem delay, age, gender, freezing method, storage duration, agonal state and brain ischaemia.

Results

Our results revealed that only prolonged agonal state and ischaemic brain damage influenced brain tissue pH next to repeated freeze/thaw cycles.

Conclusions

pH measurement in brain tissue is a good indicator of premortem events in brain tissue and it signals limitations for post mortem investigations.

Keywords: agonal state, brain banking, brain ischaemia, human post mortem brain tissue, pH

Introduction

Human brain research requires well-characterized and high-quality human brain specimens that have been acquired and processed using standardized procedures. Such tissue characterization includes patient demographics and clinical and pathological diagnoses, as well as tissue-specific information, such as agonal state, post mortem delay (PMD) and time in storage. The main goal of BrainNet Europe II, a network of 19 established brain banks across Europe, is to facilitate the utilization of human brain tissue in research. A simple biochemical indicator of tissue quality is required in order to establish the most appropriate human tissue specimens for biochemical studies.

Compared with animal tissues, which are handled in a controlled manner, post mortem artefacts and the effects of agonal conditions prior to death are additional variables that may affect the biochemical properties of human brain tissue. Previous studies recommend pH as an indicator for tissue quality, although the number of variables assessed in most studies has been limited. There is consensus that the brain region sampled [1,2] and the time in storage [3,4] do not influence tissue pH. However, controversy remains regarding the effects of agonal state and PMD. Studies have found that these parameters have either no influence [5–7] or a significant influence [8] on tissue pH. Previous studies have also established that ischaemia can change neurotransmitter and neuropeptide concentrations [6], enzyme activities [9,10] and mRNA preservation [11], supporting the concept that agonal state significantly influences the biochemistry of brain tissue. The aim of this study was to assess brain pH as possible means to predict tissue quality in the context of age, gender, sample origin, dead body storage, agonal state, diagnosis, brain region, storage time, tissue packaging and freezing methods, and PMD.

Materials and methods

Brain samples

Post mortem human brain tissue was obtained from six European brain bank centres (BBCs) organized in BrainNet Europe II: Barcelona, London, Kuopio, Würzburg Neuro-pathology together with Würzburg Psychiatry and Göttingen. Additionally, the neuropathological departments of the Universities of Tübingen and Münster (both members of BrainNet Germany) provided cases for this study. The Australian BBCs in Sydney and Victoria contributed cases with clinically well-documented agonal state. Whole human brains were obtained with the consent of the next of kin and according to the guidelines of the National and Local Ethics Committees. Causes of death were ascertained from clinical notes, autopsy reports or death certificates.

In preparation for routine neuropathological examination, the brain was divided mid-sagittally and one hemisphere was immersed in 4.5% paraformaldehyde for 3–4 weeks. The remaining half was cryopreserved following coronal slicing for cortical sampling, sagittal slicing for sampling the cerebellum and transverse sectioning of the brain stem. Tissue samples were snap-frozen on brass plates, cooled in dry ice and stored at −80°C until requested for experimental use. A neuropathological assessment was completed by a macroscopic and histo-logical examination. Because the tissue was collected from different institutions, detailed information concerning tissue preparation and storage was examined.

A total of 291 samples from 89 control cases (Table S1), defined by having no history of any neurological or neuropsychiatric disease confirmed by histo-pathological examination, were available. The gender distribution was balanced, with 149 male and 142 female samples. Furthermore, a group of 48 samples from 27 pathological cases (33 male and 15 female samples) was analysed, comprising 15 samples with global brain ischaemia (condition after resuscitation) and 12 samples with regional ischaemia (brain infarct). Both acute and subacute infarcts were included, as well as haemorrhagic infarcts; in some cases only tissue from the border area of the lesion (penumbra) was available (Table S2). For this study, frozen samples from the frontal lobe, gyrus cinguli, striatum and cerebellum were available in most cases. Detailed information about age (ranging from 0 to 98 years), PMD (ranging from 1 to 109 h) and storage time (ranging from 0 to 156 months) were provided for all cases. Demographic details about the samples are summarized in Tables S1 ans S2.

Measurement of tissue pH

The pH was determined on fresh tissue immediately after the dissection and on blocks of frozen tissue after thawing. As postulated by Ravid et al. [4], and Alafuzoff and Winblad [3], pH is stable during storage and the values were therefore comparable. The tissue was manually homogenized without dilution using a micropistill. pH values were measured at room temperature from frontal cortex, striatum, gyrus cinguli and cerebellum, using a pH-meter (MP120, Mettler-Toledo, Greifensee, Switzerland) previously calibrated with two standards (pH 4.00 and pH 7.00). For each sample, the determinations were made in duplicate. Some of our providers measured pH on diluted tissue homogenates. We used an experimental approach to compare these two methods. Therefore, we homogenized the brain tissue in 10 volumes of distilled water adjusted to pH 7 (1:10 w/v) and measured the pH with a pH-meter.

Agonal state scoring

As premortem events influence the biochemical quality of brain tissue [11], a 3-point scale was used to classify the agonal state of the patient (adapted from Hardy et al. [5]). The categorization is as follows: (i) rapid death due to violent or natural causes, defined as the sudden, unexpected death of people who had apparently been reasonably healthy. The most frequent cause of death in this group was a myocardial infarction; (ii) intermediate death: this group consisted of patients who were ill but whose deaths were unexpected. They could be classified as neither sudden deaths nor slow deaths; and (iii) slow death, defined as a death after an illness with a prolonged terminal phase. Typically, these patients died from cancers, cerebrovascular disease or bronchopneumonia. A clinical record was available in most cases. Therefore, a retrospective grading of agonal state was done. Samples from the Australian BBCs were already well categorized concerning the agonal state.

Evaluation of post mortem factors

In addition to clinical and neuropathological diagnosis, the assessment of PMD, the elapsed time between death and the freezing, is a frequently utilized measure of the quality of post mortem brain specimens. The storage time is the interval from freezing the tissue at −80°C until experimental use. Owing to the variety of brain banks involved, we were interested in a precise knowledge of storage and preparation methods. We addressed a questionnaire on this topic to the different BBCs. Concerning the storage temperature before dissection, the BBCs in Münster and Tübingen kept the dead body at room temperature, whereas the remaining eight centres stored it at 4°C. For freezing the tissue the BBCs in Göttingen and Münster used liquid nitrogen, whereas the others used dry ice. Another variation that could influence tissue quality was the packing modality. Only the BBCs in Würzburg and Barcelona used aluminium foil; in contrast, other BBCs used plastic bags.

Statistical methods

Mean values with standard deviation (SD) are reported to describe the data. Analysis of variance (anova) was performed to investigate the influence of many different factors (sample origin, diagnosis, age, gender, PMD, agonal state, dead body storage, brain region sampled, freezing method and package of tissue, and time in storage) on the target variable pH mean. P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Multivariate analysis was not possible. The analysis was done using spss 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

pH and tissue sample source

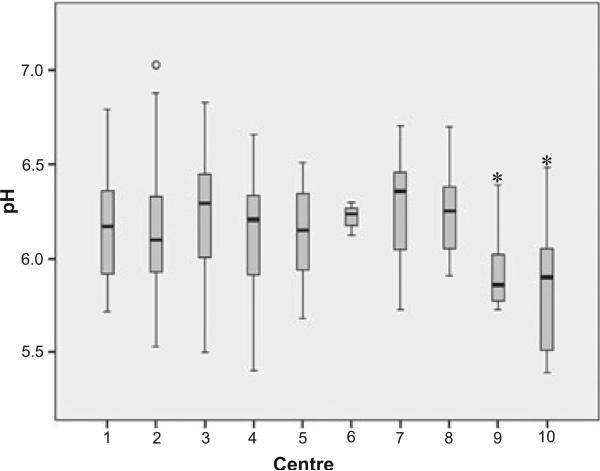

We assessed pH levels in all control samples and compared them with respect to tissue origin. An overview of the results is given in Figure 1. In human control samples, pH varied regardless of tissue origin from 5.40 to 7.03 with a mean of 6.18 ± SD 0.28 (n = 271), whereas the mean pH values from Würzburg Psychiatry (n = 6, pH 5.94 ± SD 0.24) and Göttingen (n = 20, pH 5.81 ± SD 0.32) were significantly lower (anova, P < 0.001) than those from other BBCs. These samples were characterized by repeated freeze/thaw cycles. The average pH was not significantly different among the remaining BBCs and, therefore, the samples from these two outlying centres (n = 26) were excluded from further analyses.

Figure 1.

Boxplot of pH values from control cases by tissue source: (1) Barcelona (n = 33, pH 6.17 ± SD 0.30); (2) Würzburg Neuropathology (n = 63, pH 6.14 ± SD 0.31); (3) Münster (n = 15, pH 6.23 ± SD 0.39); (4) Kuopio (n = 32, pH 6.14 ± SD 0.30); (5) London (n = 468, pH 6.15 ± SD 0.23); (6) Tübingen (n = 3, pH 6.22 ± SD 0.09); (7) Sydney (n = 52, pH 6.28 ± SD 0.25); (8) Victoria (n = 19, pH 6.24 ± SD 0.23); (9) Würzburg Psychiatry (n = 6, pH 5.94 ± SD 0.24); (10) Göttingen (n = 20, pH 5.81 ± SD 0.32). Samples from Würzburg Psychiatry (9) and Göttingen (10) had significantly lower pH values compared with the remaining centres (*P < 0.001). Those samples were repeatedly frozen and thawed. Overall mean (n = 265, pH 6.18 ± SD 0.28). anova, *P < 0.05.

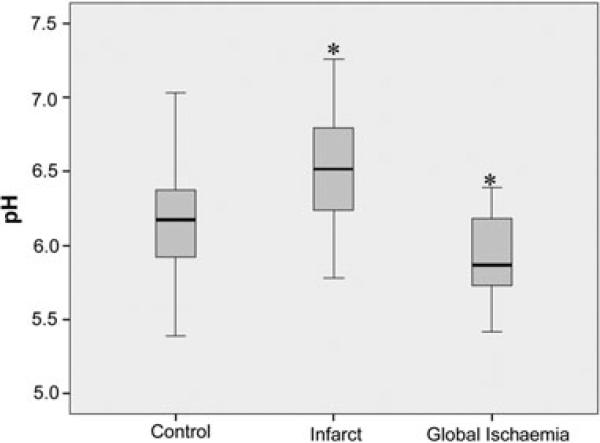

pH in pathological vs. control samples

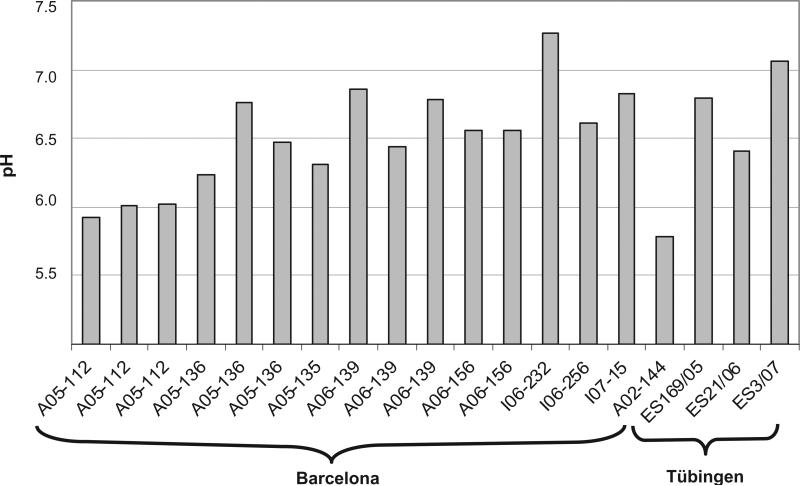

The tissue samples from cases with global ischaemia (n = 48) were compared with controls (n = 265). The pH values in global ischaemia ranged from 5.42 to 6.39 with a mean of 5.94 ± SD 0.28, and were statistically lower than control values (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). In tissue samples from brain infarcts (n = 18) pH values were highly variable (range, 5.78 to 7.26; mean, 6.50 ± SD 0.41), but were significantly higher overall than control values (P < 0.001) (Figure 2). This group included samples from acute (ranging from 1–4 days)and subacute infarcts (5–30 days) [12], as well as samples from haemorrhagic lesions. Figure 3 summarizes the pH values in the infarct samples.

Figure 2.

Boxplot diagram of pH from controls (n = 265, pH 6.18 ± SD 0.28), infarct (n = 18, pH 6.51 ± SD 0.41; P < 0.001) and global ischaemia samples (n = 48, pH 5.94 ± SD 0.28; P < 0.001). There were significant differences (*P < 0.001) between the infarct and control groups, and also between the global ischaemia and control groups. anova, *P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

pH values for single-infarct samples. The range among the samples from 5.78 to 7.26 illustrates that this is a heterogeneous group. Overall mean (n = 19, pH 6.5 ± SD 0.43).

pH in various brain regions

Based on the observation that the tissue source has no influence on pH in most controls, but concerned that temperature gradients between outer and inner regions could occur, we compared the control values between the various brain regions sampled (frontal cortex, gyrus cinguli, striatum and cerebellum). An overview of the results is depicted in Figure 4. We confirm that pH measurement of one brain region is representative for the whole brain. This was further confirmed in a few samples from other brain regions such as the hippocampus and pallidum (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Boxplot diagram of pH values from control samples by brain region: frontal cortex (n = 73, mean = 6.19 ± SD 0.29), cerebellum (n = 62, mean = 6.14 ± SD 0.27), striatum (n = 63, mean = 6.17 ± SD 0.29) and gyrus cinguli (n = 63, mean = 6.20 ± SD 0.29). There is no significant difference in pH among brain regions.

pH, gender and age

Gender had a significant influence on pH in the control samples (P < 0.001). Men had slightly higher pH values (pH 6.26 ± SD 0.27) than women (pH 6.09 ± SD 0.28), even across different ages (Figure 5b,d).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot diagram with linear regression line of pH distribution for PMD [post mortem delay, (a)], age (b) and storage time (c) reveals no significant relationship. A significant relationship was found for gender (d) (*P < 0.001): men had higher pH values (pH 6.27 ± SD 0.27) than women (pH 6.09 ± SD 0.28) shown in boxplot in (d). anova, *P < 0.05.

pH, PMD and storage time

There was no correlation between pH and PMD or time in storage (Figure 5c).

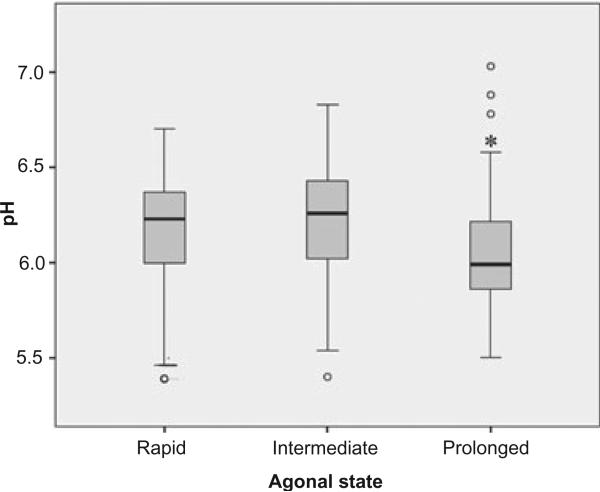

pH and agonal state

Control samples were divided according to the rapidity of death into a fast (n = 108, pH 6.23 ± SD 0.25), an intermediate (n = 58, pH 6.22 ± SD 0.28), and a more slowly dying group (n = 63, pH 6.07 ± SD 0.29) (see materials and methods). The more slowly dying group had significantly lower pH values than the fast group (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Boxplot diagram of pH in relation to agonal state duration: prolonged (n = 63, pH 6.07 ± SD 0.29), intermediate (n = 58, pH 6.22 ± SD 0.28) and rapid (n = 108, pH 6.23 ± SD 0.25). Prolonged agonal state samples had significant lower pH values (*P < 0.001) than rapid death samples; anova, *P < 0.05.

pH and methodological aspects relating to sampling

The influence of factors including body storage, freezing method, and tissue packaging on pH was evaluated. We found that none of these parameters significantly influenced pH. However, we did confirm that pH is lower in native undiluted tissue compared with diluted tissue homogenates (data not shown, see also Hardy et al. [5]).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to ascertain the utility of pH as indicator for the quality of post mortem brain tissue used in neuroscientific research. The influence of premortem and post mortem factors was investigated in a large series of brain samples provided by 10 different BBCs in Europe and Australia, including control and pathological cases.

We chose agonal state and brain ischaemia as representative factors that are operative prior to death. Events such as hypoxia and coma are often characteristic of a prolonged agonal phase. A clear distinction between rapid and slow modes of death was possible for our cases. We could demonstrate that a prolonged terminal phase is associated with significant lower brain pH compared with rapid death. Our observation supports previous studies that found a negative correlation between pH and the accumulation of brain lactate due to anaerobic glycolysis in prolonged agonal state specimens [6,9,10].

Global brain ischaemia leads to anaerobic glycolysis, which increases lactate and lowers pH [5,10,13]. In keeping with this observation, we could demonstrate significantly lower pH values in the group of samples from patients that died, for example, after efforts of resuscitation, compared with control samples.

In contrast, samples with regional brain ischaemia revealed significantly higher pH values compared with control samples. This result is due to the heterogeneous collection of samples. In samples with the central infarct area, the pH is generally low, as described in cases with global ischaemia. In addition, the ischaemic penumbra is a dynamic zone with highly variable pH values, as demonstrated by Meyer et al. [14] in animal models. Within the ischaemic penumbra, acidic foci develop that do not follow a vascular distribution and have microscopic evidence of ischaemic neuronal injury [15]. This suggests that there is a cortical selective vulnerability regarding pH regulation and these acidic foci may lead to recruitment of the ischaemic penumbra into infarction [16]. Moreover, during the reperfusion period in incomplete, reversible ischaemia, the tissue pH may reach above physiological values even in the presence of high lactate [14,17–19].

Although we have not addressed RNA integrity in this study, conflicting results from recent studies should be discussed in the context of pH. Unpredictable, and often suboptimal, preservation of RNA can complicate RNA studies in post mortem brain tissue. RNA is susceptible to post mortem storage delays and temperature fluctuations, and pH is not a reliable indicator of changes in these variables [20]. In line with this, Ervin et al. [21] demonstrated the partial degradation of RNA in cerebrospinal fluid without measurable changes in pH, indicating that pH is not always a reliable measure of tissue integrity. However, studies have demonstrated the preservation of mRNA species [6] and RNA [22], with a strong correlation with pH. Therefore, pH can provide a basic estimation concerning agonal state (especially when clinical records are not available) or other variables that can influence tissue quality.

A question of interest was whether the pH is comparable among the different tissue sources. A notable finding was that the pH range of control brain samples was similar for the majority of BBCs. Only two centres provided tissue that had undergone repeated freeze/thaw cycles, and samples from those two centres had significant lower pH values (pH < 6.0) compared with those from other centres. Among the examined post mortem conditions, only the disruption of the freezing chain seems to be reflected in pH changes.

Furthermore, our measurements in the frontal cortex, cingulate gyrus, striatum and cerebellum revealed no consistent differences in tissue pH across the brain regions. Furthermore, pH appears to be relatively uniform across the brain, as Hardy et al. [5] found a linear correlation between cortical pH and pH values from the medulla oblongata and cerebrospinal fluid. This result was also supported by other studies [1,7,23] that recommend measurement of one brain region to act as a surrogate for total brain pH. Nevertheless, RNA integrity can vary between brain regions [20].

In this study, we were able to examine a wide range of data because our tissue collection contains diverse specimens. We found a significant difference between male and female patients, with women having lower pH values compared with men, but this was not the focus of our study.

Our results provide evidence that age has no influence on brain pH. This finding supports a comparative study of the frontal cortex by Preece and Cairns [8]. However, an inverse relationship between pH and age was reported in the brain in a study by Harrison et al. [7], and in post mortem ventricular fluid by Ervin et al. [21].

Our results revealed no correlation between PMD and brain pH. In previous studies, short PMD was the hallmark of high tissue quality. This statement has been revised as high-molecular-weight DNA has been successfully extracted from cerebral cortex up to 20 days post mortem [24]. Additionally, PMD does not appear to significantly affect the recovery of total RNA [8,21,25,26]. Our results concerning brain pH are concordant with other studies that have demonstrated that pH does not appear to change as a function of post mortem interval [4,6].

The storage time of brain specimens represents another post mortem factor that may affect the outcome of a study. Our results demonstrated that the storage time had no influence on brain tissue pH. This is consistent with previous studies that revealed that pH is stable during freezer storage [3,4,7]. In our study, the storage temperature of the corpse seems not to influence pH, given that two BBCs kept it at room temperature and not at 4°C. However, this was not a systematic approach; this result is based on only a few samples, and is therefore not representative.

Conclusion

Our studies revealed that the pH of post mortem brain tissue is less dependent on factors associated with tissue handling and PMD, and more dependent on factors such as agonal state and ischaemia prior to death. We can therefore conclude that pH may serve as a useful and easily applicable initial screening procedure in the assessment of post mortem brain tissue for neuroscientific research, in order to better recognize the limitations of particular tissues for use in specific studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the European Commission under the Sixth Framework Program (BrainNet Europe II, LSHM-CT-2004-503039). We thank all tissue donors from the BrainNet Europe II Consortium and the BrainNet Germany, particularly Werner Paulus, for providing helpful support. Tissues from Australia were received from the New South Wales Tissue Resource Centre and/or the Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute Tissue Resource Centre, which is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, University of Sydney, Prince of Wales Medical Research Institute, Schizophrenia Research Institute, National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and New South Wales Department of Health. We thank Hannelore Schraut for technical assistance and Daniela Keller for statistical support.

Footnotes

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Table S1. Demographic characteristics for control cases

Table S2. Demographic characteristics for pathological cases

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Johnston NL, Cervenak J, Shore AD, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Multivariate analysis of RNA levels from postmortem human brains as measured by three different methods of RT-PCR. Stanley Neuropathology Consortium. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;77:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(97)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spokes EG, Garrett NJ, Iversen LL. Differential effects of agonal status on measurements of GABA and glutamate decarboxylase in human post-mortem brain tissue from control and Huntington's chorea subjects. J Neurochem. 1979;33:773–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alafuzoff I, Winblad B. How to run a brain bank: potentials and pitfalls in the use of human post-mortem brain material in research. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1993;39:235–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravid R, Van Zwieten EJ, Swaab DF. Brain banking and the human hypothalamus-factors to match for, pitfalls and potentials. Prog Brain Res. 1992;93:83–95. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)64565-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy JA, Wester P, Winblad B, Gezelius C, Bring G, Eriksson A. The patients dying after long terminal phase have acidotic brains; implications for biochemical measurements on autopsy tissue. J Neural Transm. 1985;61:253–64. doi: 10.1007/BF01251916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kingsbury AE, Foster OJ, Nisbet AP, Cairns N, Bray L, Eve DJ, Lees AJ, Marsden CD. Tissue pH as an indicator of mRNA preservation in human post-mortem brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:311–18. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison PJ, Heath PR, Eastwood SL, Burnet PW, McDonald B, Pearson RC. The relative importance of pre-mortem acidosis and postmortem interval for human brain gene expression studies: selective mRNA vulnerability and comparison with their encoded proteins. Neurosci Lett. 1995;200:151–4. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)12102-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preece P, Cairns NJ. Quantifying mRNA in postmortem human brain: influence of gender, age at death, postmortem interval, brain pH, agonal state and inter-lobe mRNA variance. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2003;118:60–71. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(03)00337-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry EK, Perry RH, Tomlinson BE. The influence of agonal status on some neurochemical activities of postmortem human brain tissue. Neurosci Lett. 1982;29:303–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90334-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yates CM, Butterworth J, Tennant MC, Gordon A. Enzyme activities in relation to pH and lactate in postmortem brain in Alzheimer-type and other dementias. J Neurochem. 1990;55:1624–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrison PJ, Procter AW, Barton AJ, Lowe SL, Najlerahim A, Bertolucci PH, Bowen DM, Pearson RC. Terminal coma affects messenger RNA detection in post mortem human temporal cortex. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1991;9:161–4. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(91)90143-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chuaqui R, Tapia J. Histologic assessment of the age of recent brain infarcts in man. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1993;52:481–9. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wester P, Bateman DE, Dodd PR, Edwardson JA, Hardy JA, Kidd AM, Perry RH, Singh GB. Agonal status affects the metabolic activity of nerve endings isolated from postmortem human brain. Neurochem Pathol. 1985;3:169–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02834269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer FB, Anderson RE, Sundt TM, Jr, Yaksh TL. Intracellular brain pH, indicator tissue perfusion, electroencephalography, and histology in severe and moderate focal cortical ischemia in the rabbit. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1986;6:71–8. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1986.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson RE, Tan WK, Meyer FB. Brain acidosis, cerebral blood flow, capillary bed density, and mitochondrial function in the ischemic penumbra. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 1999;8:368–79. doi: 10.1016/s1052-3057(99)80044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodd PR, Hambley JW, Cowburn RF, Hardy JA. A comparison of methodologies for the study of functional transmitter neurochemistry in human brain. J Neurochem. 1988;50:1333–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb03013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kogure K, Busto R, Schwartzman RJ, Scheinberg P. The dissociation of cerebral blood flow, metabolism, and function in the early stages of developing cerebral infarction. Ann Neurol. 1980;8:278–90. doi: 10.1002/ana.410080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomlinson FH, Anderson RE, Meyer FB. Acidic foci within the ischemic penumbra of the New Zealand white rabbit. Stroke. 1993;24:2030–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.2030. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paschen W, Djuricic B, Mies G, Schmidt-Kastner R, Linn F. Lactate and pH in the brain: association and dissociation in different pathophysiological states. J Neurochem. 1987;48:154–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb13140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrer I, Martinez A, Boluda S, Parchi P, Barrachina M. Brain banks: benefits, limitations and cautions concerning the use of post-mortem brain tissue for molecular studies. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9:181–94. doi: 10.1007/s10561-008-9077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ervin JF, Heinzen EL, Cronin KD, Goldstein D, Szymanski MH, Burke JR, Welsh-Bohmer KA, Hulette CM. Postmortem delay has minimal effect on brain RNA integrity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1093–9. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c196a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stan AD, Ghose S, Gao XM, Roberts RC, Lewis-Amezcua K, Hatanpaa KJ, Tamminga CA. Human postmortem tissue: what quality markers matter? Brain Res. 2006;1123:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mexal S, Berger R, Adams CE, Ross RG, Freedman R, Leonard S. Brain pH has a significant impact on human postmortem hippocampal gene expression profiles. Brain Res. 2006;1106:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ludes B, Pfitzinger H, Mangin P. DNA fingerprinting from tissues after variable postmortem periods. J Forensic Sci. 1993;38:686–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barton AJ, Pearson RC, Najlerahim A, Harrison PJ. Pre- and postmortem influences on brain RNA. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson SA, Morgan DG, Finch CE. Extensive postmortem stability of RNA from rat and human brain. J Neurosci Res. 1986;16:267–80. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490160123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.