Abstract

Background

Previous studies showed that Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans interact synergistically in dual species biofilms resulting in enhanced mortality in animal models.

Methodology/Principal Findings

The aim of the current study was to test possible candidate molecules which might mediate this synergistic interaction in an in vitro model of mixed biofilms, such as farnesol, tyrosol and prostaglandin (PG) E2. In mono-microbial and dual biofilms of C.albicans wild type strains PGE2 levels between 25 and 250 pg/mL were measured. Similar concentrations of purified PGE2 significantly enhanced S.aureus biofilm formation in a mode comparable to that observed in dual species biofilms. Supernatants of the null mutant deficient in PGE2 production did not stimulate the proliferation of S.aureus and the addition of the cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin blocked the S.aureus biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner. Additionally, S. aureus biofilm formation was boosted by low and inhibited by high farnesol concentrations. Supernatants of the farnesol-deficient C. albicans ATCC10231 strain significantly enhanced the biofilm formation of S. aureus but at a lower level than the farnesol producer SC5314. However, C. albicans ATCC10231 also produced PGE2 but amounts were significantly lower compared to SC5314.

Conclusion/Significance

In conclision, we identified C. albicans PGE2 as a key molecule stimulating the growth and biofilm formation of S. aureus in dual S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms, although C. albicans derived farnesol, but not tyrosol, may also contribute to this effect but to a lesser extent.

Introduction

The first study suggesting a specific interaction between Staphylococcus (S.) aureus and Candida (C.) albicans was published in 1976 [1]. Since then, a number of studies corroborated this result and showed a synergistic interaction of S. aureus and C. albicans with enhanced mortality in animal models [2–4].

In vitro studies of complex microbial communities show that intra-species and inter-species interactions are mediated via small molecules released into the extracellular environment, i.e. quorum sensing molecules, extracellular virulence factors, or secondary metabolites [5–7].

Candida albicans regulates virulence traits through the production of at least two quorum-sensing (QS) signal molecules, E,E-farnesol and tyrosol, both affecting dimorphism and biofilm formation in C. albicans [8–10]. Furthermore, C. albicans farnesol down-regulates the production of pyocyanin in Pseudomonas (P.) aeruginosa [11] and inhibits biofilm formation and lipase activity in S. aureus [12,13].

Candida albicans is a commensal microorganism in healthy individuals but is capable of causing disseminated or chronic infections when the host mucosal barrier is breached and the immune response is inadequate. In vivo, inflammation is mediated by the production of eicosanoids including prostaglandins and leukotrienes. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), an oxygenated metabolite of arachidonic acid, is known to regulate the activation, maturation, cytokine release and migration of the mammalian cells, particularly those involved in innate immunity [14–18]. Interestingly, C. albicans produces authentic PGE2 from external arachidonic acid [19], which is upregulated during biofilm formation suggesting that PGE2 may represent a significant virulence factor in biofilm-associated infections.

In order to evaluate the possible effect of PGE2 on bacterial biofilms, we established a S. aureus/C. albicans dual species biofilm model. Using this model we were able to replace the stimulatory activity of C. albicans on S. aureus by synthetic purified PGE2, suggesting that this metabolite plays an important role in the interaction of S. aureus and C. albicans in biofilms.

Material and Methods

Staphylococcus aureus and C. albicans strains

The following strains were used in this study: Staphylococcus (S.) aureus 31883 small colony variant (SCV) strain isolated from a sputum sample of a patient suffering from cystic fibrosis; S. aureus 19552 clinical isolate derived from the throat of a cystic fibrosis patient (non-SCV phenotype); Candida (C.) albicans 31883 isolated from a sputum sample of a patient suffering from cystic fibrosis; C. albicans ATCC10231 wild type (wt) strain (laboratory strain; farnesol-deficient); C. albicans SC5314 wt strain (laboratory strain; farnesol producer, [20]); C. albicans M35 (prototrophic reference strain; same as CAF2-1, but ura3-/URA3 [21]); C. albicans M134 (prototrophic reference strain; same as CAI4, but ura3-/- rps1::URA3/RPS; [22]; further ura3-/-); C. albicans M1096 (prototrophic; same as CAI4, but ura3-/- fet31-/-::URA3; [23]; further ura3-/-fet31-/-).

Clinical isolates were cultured from routine diagnostic samples which were sent to the Institute of Medical Microbiology. The samples were processed in the diagnostic laboratory under the special guidance of the author as described below. After homogenization with sterile saline (1:1) the sputum samples were plated on various agar plates and incubated at 37°C and at 30°C for two days, respectively, and at 25°C for further three days. The throat swabs were processed in a similar manner without homogenization. After visible growth the colonies were identified by the use of mass spectrometry (Vitek2 MS; Biomerieux, France) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. All strains identified from patients with cystic fibrosis were routinely stored at -70°C using the Microbank system as recommended by the manufacturer (Bestbion; Colonia, Germany).

For the use in this study, clinical strains were cultured from the Microbank system on Columbia agar plates containing 5% sheep blood (Beckton Dickinson) and incubated over night at 37°C. Subcultures on blood agar plates were incubated for further 24h under the same conditions. From these subcultures glycerin stocks (99.9%; Calbiochem, Heidelberg, Germany) were prepared and stored at -70°C until further use.

Dual S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms

Three to five S. aureus colonies grown from glycerin stocks were inoculated in 5mL trypcase soy broth (TSB-T; Biomerieux, Nürtingen, Germany) and incubated over night at 37°C with agitation of 180 rpm. C. albicans cells from glycerin stocks were propagated overnight in 100mL Yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) medium (Sigma, Hannover; Germany) at 30°C on an orbital shaker at 180 rpm. Under these conditions all strains grow in the budding yeast phase. Candida cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed twice in sterile phosphate buffered saline (1xPBS; Sigma), re-suspended and adjusted to a cellular density equivalent to 3x106 cells/mL. S. aureus cells were adjusted to an optical density of 0.02 in RPMI1640 using a spectrophotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) which is equivalent to approximately 3x106 cells/mL [24]. One mL of each microbial suspension was added to each well of a 12-well plate (Greiner, Frickenhausen, Germany). Biofilms were incubated in RPMI1640 buffered with HEPES and supplemented with L-glutamine and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany) for the appropriate time at 37°C with 75 rpm of agitation in humid atmosphere. Medium was changed daily. Under these conditions S. aureus and C. albicans formed stable and reproducible mono-microbial and mixed biofilms which was tested using one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) as described elsewhere [25,26]. After the appropriate time of incubation supernatants were removed. Biofilms were scraped from the bottom of the wells and homogenized with Sputasol liquid (50μg/mL; Thermo Fisher) as described by Efthimiadis et al. [27]. Cells were collected by centrifugation (1100xg for 5 min) and washed twice in sterile PBS. The inoculum was confirmed by quantitative culture (serial diluted 10-fold) on mannitol salt agar (MSA2 agar; Biomerieux) after 24h of incubation at 37°C for S. aureus or on Chromagar CANDIDA (BD) after 48h at 30°C for C. albicans.

Crystal violet staining

Mono-microbial and mixed biofilms were stained with crystal violet (CV) solution as described by Peeters et al. [28]. Briefly, biofilms cultured in 96-well plates were fixed with methanol. Then, 0.2% crystal violet solution was added to each well and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. Excess CV was removed by washing under running tap water and bounded CV was released by 33% acetic acid (Sigma). Absorbance was measured at 570 nm.

Determination of the prostaglandin concentration

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production was measured from supernatants of different mono-microbial and dual biofilms using a monoclonal PGE2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Supernatants were collected from the biofilms after the appropriate time point, centrifuged at 8000xg, filtered twice by using a 0.22 μm syringe filter (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and stored at -80°C. To confirm, that the supernatants yielded no living cells of S. aureus and C. albicans, 100 μl of the supernatants were plated onto blood agar plates and incubated for 48h at 37°C and for further 48h at 30°C. All supernatants processed by this method were cell-free. In serum, PGE2 is rapidly degraded into unstable intermediates [19], i.e. 15-keto-13, 14-dihydro-PGE2, which were determined with a PGE2 metabolite kit (Cayman Chemicals). The PGE2 metabolite kit converts the unstable intermediates into stable measurable derivative serving as marker for the PGE2 production. Background levels of PGE2 detected in RPMI 1640 with and without FBS were subtracted from experimental samples.

Purified substances

Purified tyrosol, farnesol and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions of tyrosol (2-4-hydroxyphenylethanol) and farnesol were dissolved in DMSO. PGE2 stock solution (1mg/mL) was prepared in ethanol and further diluted in 1xPBS. Established 24h old S. aureus biofilms were incubated overnight in the presence of the appropriate drugs, biofilms were harvested and the numbers of colony forming units (cfu`s) were determined as described above. Control experiments revealed that DMSO and ethanol did not affect to the growth of S. aureus and C. albicans.

Inhibitors

The cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin (Sigma) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (stock solution 1mM) and further diluted in PBS prior to addition to mixed biofilms. Dual biofilms without supplements or with DMSO alone were used as control. DMSO did not influence the growth of the biofilms.

Statistical analysis

Data represent the mean plus the standard deviation of two independent experiments with three intra-assay replicates.

Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test with SigmaStat statistical software (version 2.0). P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

According to the written decision of the clinical research ethics committee of the Otto-von-Guericke University of Magdeburg the current study did not require approval by the local ethics committee because no human material or data attributable to individual patients were used.

Results

Stimulation of S. aureus by C. albicans in mixed biofilms

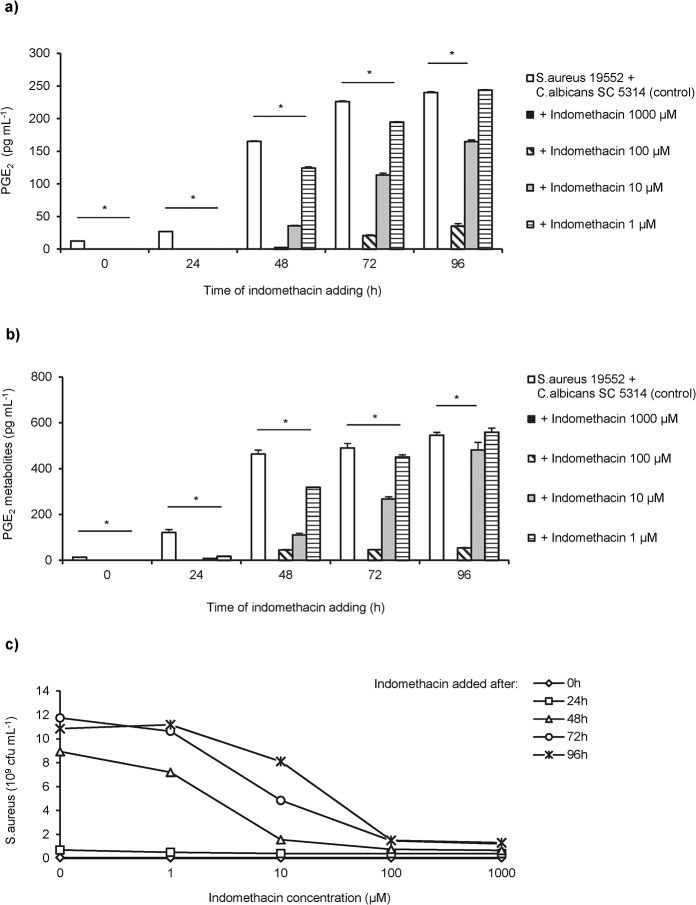

Initial mixed biofilm experiments with clinical strains of S. aureus and C. albicans showed that biofilm thickness of mixed biofilms was significantly increased compared with S. aureus mono-microbial biofilms (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. Growth kinetics of S.aureus in mono-microbial and in dual S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms.

(a) Biofilm thickness of S. aureus 19552 single (open bars) and mixed biofilms with C. albicans 31883 wt (clinical strain; striped) or C. albicans SC5314 wt (laboratory strain; solid bars) at various time points determined by staining with crystal violet. Total biofilm thickness is expressed as mean of the optical density (OD) measured at a wave length of 570 nm. Shown are the means and standard deviations of two independent experiments with 24 replicates each. (b) Quantification of S. aureus 19552 in mono-microbial (circle) and in dual species biofilms together with C. albicans clinical isolate 31883 (triangle) or C. albicans SC5314 laboratory strain (square). Shown are the mean cfu`s of S. aureus derived from two representative experiments with three intra-assay replicates. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.001) differences between mono-microbial and dual species biofilms.

Mixed biofilms yielded a significantly higher number of S. aureus colony forming units (cfu`s) compared to mono-microbial S. aureus biofilms with a dramatically increase after 72h of co-culture (Fig 1B).

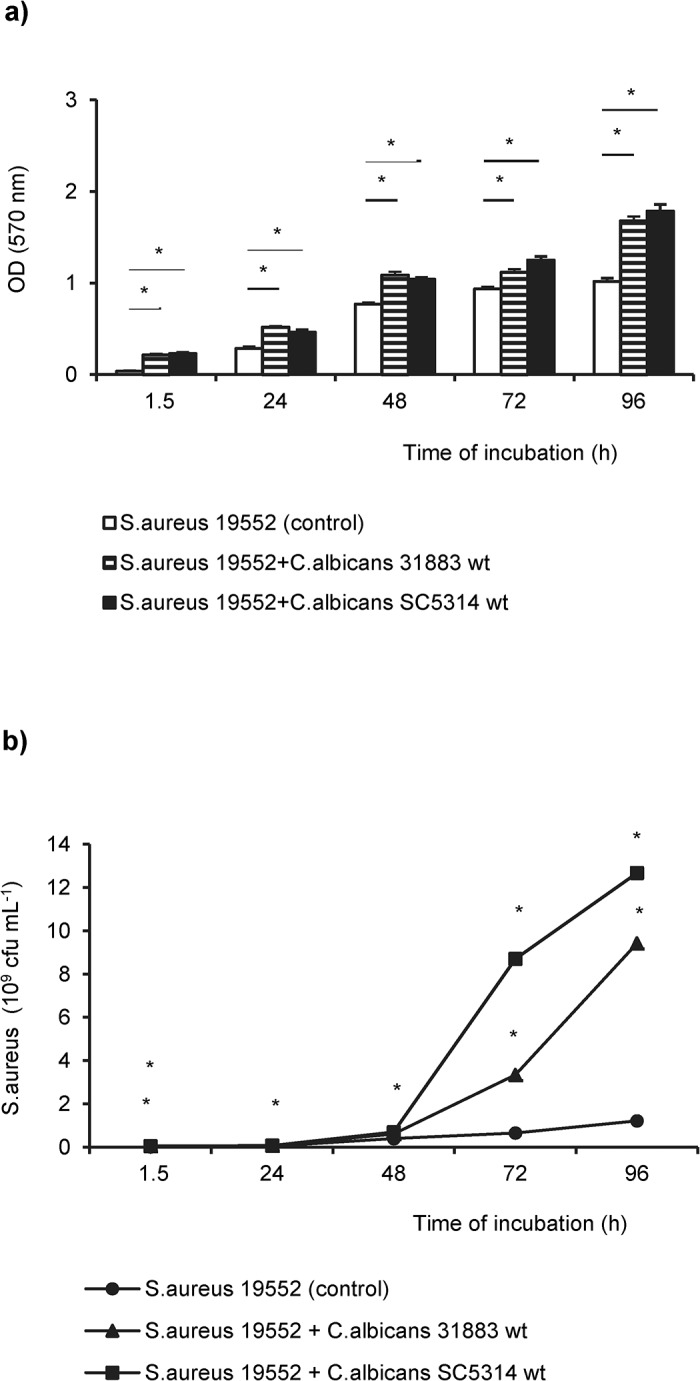

In order to investigate, if the growth-stimulating effect of C. albicans depends on the direct contact of bacteria to the hyphal network, 24h old S. aureus biofilms were incubated with cell-free supernatants from C. albicans 31883 and SC5314 diluted 1:1 with fresh medium (Fig 2A). The number of cfu`s of S. aureus increased 10-fold when supernatants derived from 72h or 96h old C. albicans biofilms were added. The strongest increase was observed with supernatants from C. albicans SC5314. Remarkably, the stimulatory activity of supernatants was heat-labile. Incubation of S. aureus with heat-treated supernatants from C. albicans mono-microbial biofilms did not promote the propagation of S. aureus (Fig 2B).

Fig 2. Growth-promoting properties of cell-free C. albicans supernatants.

(a) Supernatants removed from biofilms of two C. albicans wild type strains SC5314 and 31883, respectively, after the indicated time of incubation were added to 24h old biofilms of S. aureus 19552. (b) Heat-treated (striped) and untreated supernatants (open bars) were collected as described above and added to 24h-old S. aureus biofilms. S. aureus grown as mono-microbial biofilm was used as control (solid bars). Shown are the mean cfu and the standard deviations of two independent experiments each with three replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (p<0.001).

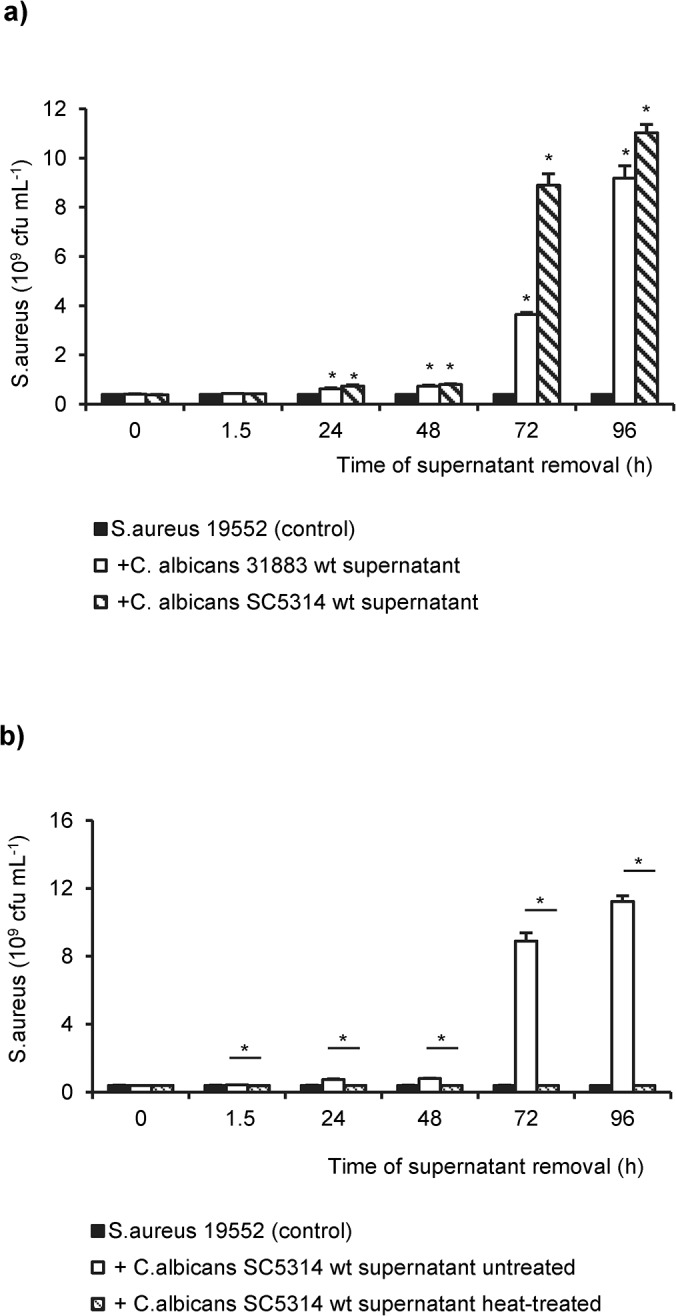

Subinhibitory concentrations of farnesol promote biofilm formation of S. aureus

In order to further define the growth-promoting activity of C. albicans culture supernatants the effect of a number of molecules secreted by C. albicans such as farnesol, tyrosol and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), were tested.

Synthetic farnesol at concentrations between 5 and 0.5 nM (Fig 3A), but not purified tyrosol, stimulated the growth of S. aureus in biofilms, whereas concentrations ≥ 0.5 μM significantly reduced the growth of S. aureus (S1 Fig).

Fig 3. Effect of farnesol on the growth of S. aureus 19552 in mono-microbial biofilms.

(a) Pre-cultered 24h old S. aureus biofilms were supplemented with different concentrations of purified farnesol and the number of cfu`s was determined. S. aureus biofilms incubated in farnesol-free medium were used as control. (b) Growth kinetics of S. aureus in dual biofilms with the farnesol-deficient C. albicans strain ATCC10231 (striped) and the farnesol producer C. albicans SC5314 (open bars). Colony forming units (cfu`s) of S. aureus derived from single species biofilms were function as control (solid bars). Shown are the mean cfu`s and the standard deviations of two representative experiments with three replicates each. Asterisks indicate significant (p<0.05) differences compared to controls.

The application of supernatants from cultures of both C. albicans SC5314 (farnesol producer) and ATCC10231 (farnesol nonproducer) significantly enhanced the growth rates of S. aureus (Fig 3B). Interestingly, the farnesol-producing strain exhibited a stronger impact to the growth and biofilm formation of S. aureus than the farnesol-negative isolate.

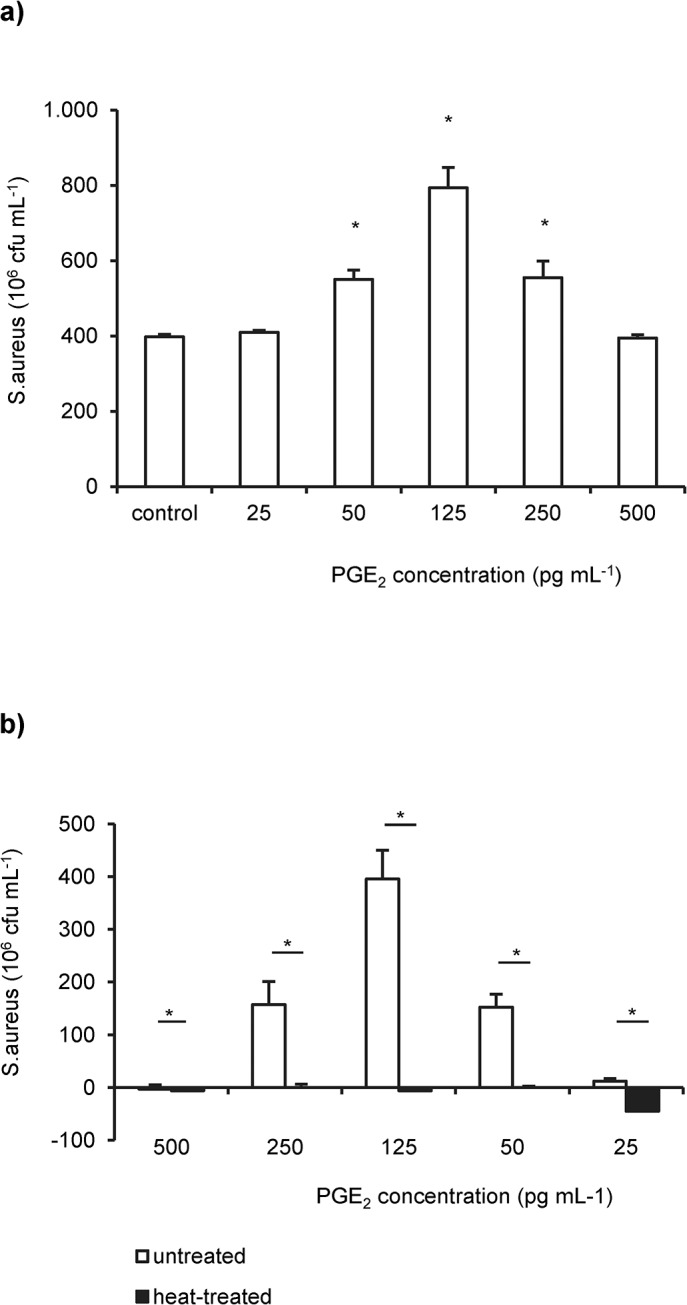

Purified PGE2 stimulates growth of S. aureus in biofilms

Next step was to analyze the effect of purified PGE2 on 24h old S. aureus biofilms. As shown in Fig 4A, purified PGE2 significantly enhanced S. aureus biofilm formation in a dose-dependent manner. The stimulatory activity of purified PGE2 was neutralized by heating treatment of the PGE2 solution (Fig 4B).

Fig 4. PGE2 stimulates the growth of S. aureus biofilms.

(a) S. aureus 19552 was grown in single species biofilms in the presence of various concentrations of purified PGE2. The mean number of colony forming units (cfu`s) from untreated S. aureus biofilms were used as control. Asteriks indicate statistically significant (p< 0.05) differences between PGE2-treated and untreated biofilms. (b) Cultures of S. aureus 19552 biofilms were supplemented with heat-treated (solid bars) and untreated (open bars) PGE2 supplemented medium. Shown are the mean number of S. aureus cfu`s normalized to the non-supplemented control as well as the standard deviations derived from two independent experiments and three replicates per experiment. Asterisks indicate significant (p< 0.05) differences between the groups.

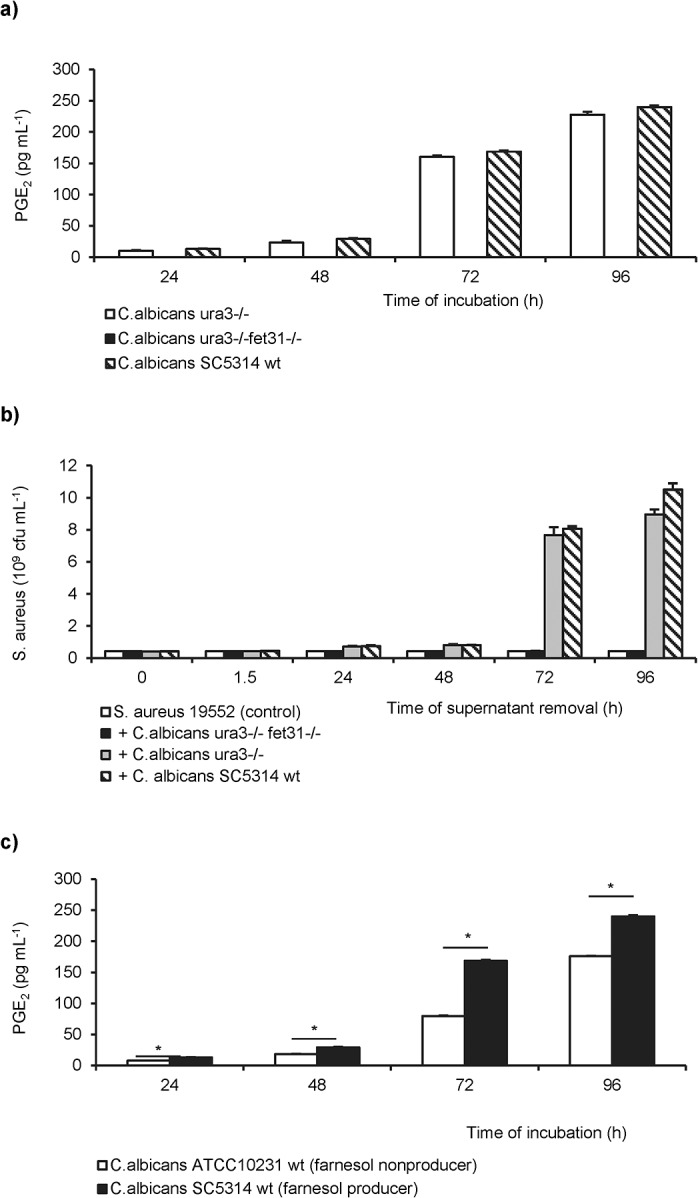

C. albicans PGE2-deficient mutant strain do not stimulate growth of S. aureus

PGE2 and its metabolites were abundantly detected in culture supernatants of C. albicans wt and reference strains, and their amount increased according to the C. albicans cell density.

In contrast, PGE2 levels of the C. albicans null mutant (ura3-/-fet31-/-), deficient in the multi-copper oxidase genes fet31, were below the detection limit of the assay (Fig 5A and S2 Fig).

Fig 5. PGE2 synthesis in C.albicans wild type and mutant strains and its effect on S. aureus biofilms.

(a) Time-dependent accumulation of PGE2 in culture supernatants of the C. albicans SC5314 wt (dashed), the reference strain ura3-/- (open bars), and the null mutant ura3-/-fet31-/- (solid bars) measured by EIA. (b) Effect of cell-free supernatants derived from C. albicans SC5314 wt (striped), from the reference (grey bars) and from the null mutant (solid bars) to the growth of established S. aureus 19552 biofilms (control; open bars) after further 24h of incubation. (c) PGE2 levels in supernatants of C. albicans ATCC10231 (farnesol nonproducer; open bars) and SC5314 (farnesol producer; solid bars) were compared. Mean and standard deviations derived from two representative experiments with three replicates per test are demonstrated. Significant differences (p<0.001) between the two groups were identified by asterisks.

The concentration of purified PGE2 inducing the growth of S. aureus were similar to the PGE2 levels measured in supernatants of C. albicans mono-microbial biofilms (Figs 4A and 5A).

To test the hypothesis that PGE2 is responsible for the stimulatory effect of C. albicans on S. aureus biofilms, the effect of cell-free supernatants derived from PGE2 producers (C. albicans SC5314 and C. albicans ura3-/-) and from the PGE2 nonproducer (C. albicans ura3-/-fet31-/-) to the growth of S. aureus was investigated (Fig 5B). Supernatants derived from the PGE2-deficient mutant were unable to stimulate the growth of S. aureus.

Interestingly, the farnesol producer C. albicans SC5314 secreted significantly higher levels of PGE2 than the farnesol-deficient strain ATCC10231 (Fig 5C).

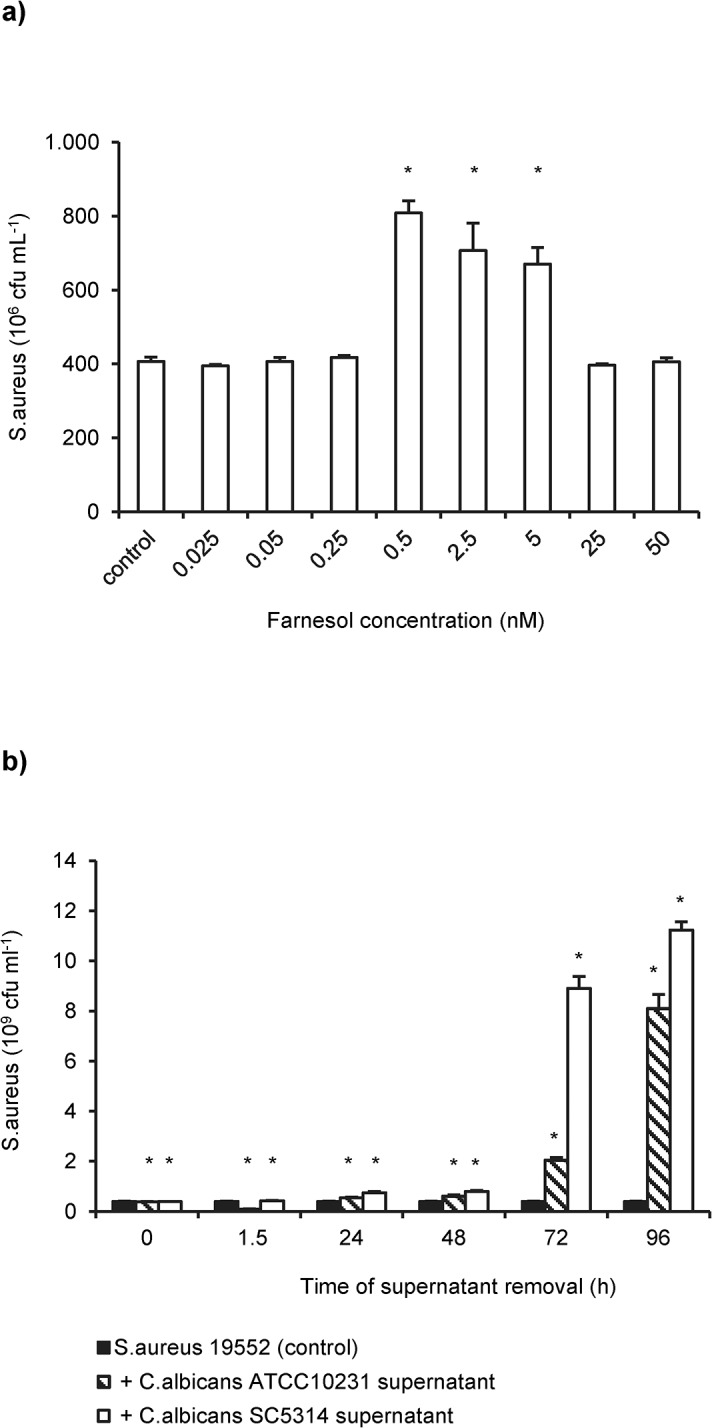

Treatment of mixed biofilms with indomethacin reduced growth of S. aureus

In addition, we tested whether the nonspecific cyclooxygenase inhibitor indomethacin can influences the stimulatory activity of C. albicans to S. aureus. Indomethacin at a concentration between 10 and 1000 pg/mL efficiently blocked the biosynthesis of PGE2 (Fig 6A) and its metabolites (Fig 6B) by C. albicans. In cultures of mixed S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms indomethacin significantly suppressed the growth of S. aureus in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 6C).

Fig 6. Indomethacin suppresses the stimulatory effect of C. albicans on S. aureus biofilms.

(a) Indomethacin was added to mixed biofilms of S. aureus 19552 and C. albicans SC5314 pre-cultured for different periods. PGE2 synthesis was measured in supernatants from indomethacin-treated and untreated (control) dual biofilms by monoclonal and (b) metabolite EIA. Asterisks indicate significant differences between indomethacin-treated cultures and untreated controls. (c) The number of S. aureus cfu`s was quantified in mixed S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms after addition of graded doses of indomethacin at the indicated time points. Untreated dual species biofilms were used as control. Shown are the results of two representative experiments with three intra-assay replicates.

Experiments performed with the S. aureus small colony variant 31338 revealed similar results.

Neither DMSO nor Indomethacin significantly affected the growth of S. aureus or C. albicans. Data are exemplarily represented for S. aureus 19552 and C. albicans SC5314 (S3 Fig).

S. aureus does not stimulate the PGE2 synthesis in C. albicans

The levels of PGE2 and of the PGE2 metabolites were not enhanced in dual biofilms of S. aureus and C. albicans wild type strains compared with C. albicans mono-microbial biofilms, indicating that S. aureus did not stimulate the release of PGE2 from C. albicans isolates (S4 Fig).

Discussion

In polymicrobial infections, biofilm formation is the predominant mode of life [29–31]. Biofilms are structured microbial communities attached to biotic or abiotic surfaces and embedded in a matrix of exopolymers to withstand the host immune response and exhibit increased resistance to antimicrobial agents [32–35]. It is estimated that 27% of nosocomial C. albicans bloodstream infections are polymicrobial, with S. aureus as the third most common organism isolated in conjunction with C. albicans [36].

In vitro studies demonstrated that the formation of S. aureus biofilms on abiotic materials in the presence of serum requires pre-coating and nutrient supplementation [37]. In order to study the interactions between C. albicans and S. aureus in mono-microbial and dual species biofilms, we have optimized an in vitro biofilm model of infection. Using this model, we observed increased growth rates of S. aureus in dual biofilms in the presence of C. albicans. In vitro studies described the formation of S. aureus microcolonies on the surface of biofilms with C. albicans serving as the underlying scaffolding [38,39]. The adherence of S. aureus on fungal hyphae was mediated by the Candida agglutinin-like protein 3 (Als3p; [40]). Studies of the protein expression during the growth of dual C. albicans/S. aureus biofilms identified 27 differentially regulated proteins, mostly involved in growth, metabolism, or stress response. Among the down-regulated staphylococcal proteins was the global transcriptional repressor of virulence factors, CodY, suggesting that the enhanced pathogenesis of S. aureus may not only be due to physical interactions [41,42].

Staib et al. [1] hypothesized the potential existence of C. albicans end-products as a substratum for a favorable growth of S. aureus. One of the C. albicans products continuously excreted in the environment is farnesol a quorum sensing molecule involved in the regulation of the fungal yeast-mycelium dimorphism. At high levels, farnesol has been shown to exhibit antimicrobial activity against various pathogens [12]. Kaneko et al. reported growth inhibition of S. aureus at concentrations of 40 μg mL-1 (equivalent to 180 μM) which is concordant with our results [43]. In this study, subinhibitory concentrations of farnesol (0.5–5 nM) promoted the biofilm formation of S. aureus, an effect already described for several antimicrobial agents [44–47]. In stationary phase cultures of C. albicans, farnesol accumulated at levels between 2 and 4 μM [8,48]. In addition, our data showed that S. aureus biofilm production was propagated by the farnesol-deficient C. albicans strain ATCC 10231 albeit at a lower level compared to the farnesol producer C. albicans SC5314, whereas the PGE2 null mutant did not enhanced the growth of S. aureus. Unlike SC5314, ATCC10231 excreted significantly lower levels of PGE2 in this experimental setting indicating that the differences in the growth-stimulating effect to S. aureus resulted from the PGE2 levels. In conclusion, it appears that PGE2 has a superior role in the induction of S. aureus biofilm formation as compared to farnesol, which, however, also supports the growth of S. aureus at low concentrations.

We demonstrated for the first time that C.albicans PGE2 may be one of the suggested end-products presumed by Staib [1]. As shown in this study, the stimulatory effect to the growth of S. aureus was not observed, when C. albicans supernatants or medium supplemented with purified PGE2 were heat treated suggesting that PGE2 is heat-sensitive. This observation is concordant with the results described by Carlson who reported increased mortality rates of mice co-infected with sublethal doses of C. albicans and S. aureus [3]. This effect could not be reproduced when either of the agents was heat inactivated.

Endogenous PGE2 maintains the integrity of the mucosal barrier in the lungs and in the gastrointestinal tract [49–51]. Mucus accumulation and overexpression of inflammatory response genes are relevant pathogenic features of cystic fibrosis (CF), a genetic disorder caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene cftr [52]. Recently, Harmon et al. demonstrated a defective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARy) function in epithelial cells which was caused by the decreased conversion of PGE2 to the PPARy ligand 15-keto-PGE2 leading to the accumulation of PGE2 [51]. As elevated levels of PGE2 have been detected in respiratory tract samples of patients suffering from cystic fibrosis [53,54] and in consideration of the results from this study, it seems to be possible that enhanced PGE2 levels may contribute to the early airway colonization due to S. aureus in patients with CF.

PGE2 was demonstrated to induce germ tube formation and to be involved in biofilm formation by C. albicans [55,56] suggesting C. albicans PGE2 to be a potential virulence factor. Despite induced endocytosis by host cells at the early stage of infection, hyphal mediated active penetration of the host tissue is the major route of invasion [57,58]. Tissue invasion by C.albicans is associated with cytokine secretion, inducing host immune response mechanisms. Phagocytosis by macrophages and neutrophils represents the first line of defense against Candida infections but intracellular killing is not always effective. One of the underlying mechanisms is the inhibition of the phagosome maturation and the nitric oxid (NO) production in macrophages after infection with C. albicans [59], an effect that may be resulted from candidal PGE2 excretion.

PGE2 is a critical molecule that regulates the activation, maturation, migration, and cytokine secretion of several immune cells, particular those of the innate immunity. In the context of infection, endogenous PGE2 inhibits the cytolytic effector function of natural killer (NK) cells, the activation, migration and production of proteolytic enzymes in granulocytes and limits the phagocytosis and pathogen-killing function of alveolar macrophages (reviewed by [14,18]. Aronoff et al. reported the negative regulatory role of endogenously produced and exogenously added PGE2 on FcRy-mediated phagocytosis of bacterial pathogens by alveolar macrophages suggesting that PGE2 derived from C. albicans may impair the local host innate immunity [60]. This suggestion is underlined by the investigations of Roux et al. who had shown that airway colonization with C. albicans inhibited phagocytosis of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa and enhanced the prevalence of bacterial pneumonia, which was reduced by antifungal treatment [61,62].

Mice inoculated with either S. aureus or C. albicans survived infection, whereas combined infection with both pathogens enhanced the mortality rate to 40–100% [3,4]. Reversely, enhanced microbial clearance and survival was demonstrated in studies with COX-2-deficient mice [63–65]. This is in line with our observation that a mutant strain of C. albicans deficient in PGE2 production did not promote the growth of S. aureus. Furthermore, in this study the non-selective cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor indomethacin that blocked PGE2 biosynthesis by C. albicans also reduced the growth of S. aureus in dual biofilms to a level observed in mono-microbial S. aureus biofilms.

Thus, treatment with indomethacin or with antifungal agents may exhibit several positive effects in patients with dual S. aureus/C. albicans infections [51,60–62].

Finally, in this study S. aureus did not enhanced the biofilm thickness of C. albicans and its PGE2 synthesis in dual biofilms compared with mono-microbial C. albicans biofilms, although bacterial peptidoglycan-derived molecules have been shown to promote C. albicans hyphal growth [66,67]. Thus, in mixed biofilms the impact of S. aureus to C. albicans remained unclear.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that PGE2 is the key molecule stimulating the growth and biofilm formation of S. aureus in dual S. aureus/C. albicans biofilms, although subinhibitory farnesol concentrations may also support this effect. Candidal PGE2 may exhibit a dual effect in S. aureus/C. albicans polymicrobial biofilms, first, by promoting fungal hyphal formation and second, by providing a proper substratum for the proliferation of S. aureus. Further characterization of the intricate interaction between these pathogens is warranted, as it may aid in the design of further therapeutic strategies against polymicrobial biolfilm infections.

Supporting Information

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Sascha Brunke (Hans Knoell Institute, Jena, Germany) for generously providing us with C.albicans M35, M134 and M1096 strains.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Staib F, Grosse G, Mishra SK. Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection (animal experiments). Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1976; 234: 450–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. deRepentigny J, Levesque R, Mathieu LG. Increase in the in vitro susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to antimicrobial agents in the presence of Candida albicans. Can J Microbiol. 1979; 25: 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carlson E. Synergistic effect of Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus on mouse mortality. Infect Immun. 1982; 38: 921–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peters BM, Noverr MC. Candida albicans-Staphylococcus aureus polymicrobial peritonitis modulates host innate immunity. Infect Immun. 2013; 81: 2178–2189. 10.1128/IAI.00265-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hogan DA, Vik A, Kolter R. A Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing molecule influences Candida albicans morphology. Mol Microbiol. 2004; 54: 1212–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kerr JR. Suppression of fungal growth exhibited by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Clin Microbiol. 1994; 32: 525–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta N, Haque A, Mukhopadhyay G, Narayan RP, Prasad R. Interactions between bacteria and Candida in the burn wound. Burns. 2005; 31: 375–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hornby JM, Jensen EC, Lisec AD, Tasto JJ, Jahnke B, Shoemaker R, et al. Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001; 67:2982–2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramage G, Saville SP, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. Inhibition of Candida albicans biofilm formation by farnesol, a quorum-sensing molecule. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002; 68: 5459–5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alem MA, Oteef MD, Flowers TH, Douglas LJ. Production of tyrosol by Candida albicans biofilms and its role in quorum sensing and biofilm development. Eukaryot Cell. 2006; 5: 1770–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cugini C, Calfee MW, Farrow JM III, Morales DK, Pesci EC, Hogan DA. Farnesol, a common sesquiterpene, inhibits PQS production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2007; 65: 896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jabra-Rizk MA, Meiller TF, James CE, Shirtliff ME. Effect of farnesol on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and antimicrobial susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006; 50: 1463–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuroda M, Nagasaki S, Ito R, Ohta T. Sesquiterpene farnesol as a competitive inhibitor of lipase activity of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007; 273: 28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Agard M, Asakrah S, Morici LA. PGE(2) suppression of innate immunity during mucosal bacterial infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013; 3: 45 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obermajer N, Wong JL, Edwards RP, Odunsi K, Moysich K, Kalinski P. PGE(2)-driven induction and maintenance of cancer-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Immunol Invest. 2012; 41: 635–657. 10.3109/08820139.2012.695417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bankhurst AD. The modulation of human natural killer cell activity by prostaglandins. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1982; 7: 85–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goto T, Herberman RB, Maluish A, Strong DM. Cyclic AMP as a mediator of prostaglandin E-induced suppression of human natural killer cell activity. J Immunol. 1983; 130: 1350–1355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kalinski P. Regulation of Immune Responses by Prostaglandin E-2. Journal of Immunology 2012; 188: 21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Erb-Downward JR, Noverr MC. Characterization of prostaglandin E2 production by Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2007; 75: 3498–3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gillum AM, Tsay EY, Kirsch DR. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1984; 198: 179–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 1993; 134: 717–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fradin C, De Groot P, Mac Callum D, Schaller M, Klis F, Odds FC, et al. Granulocytes govern the transcriptional response, morphology and proliferation of Candida albicans in human blood. Mol Microbiol. 2005; 56: 397–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eck R, Hundt S, Hartl A, Roemer E, Kunkel W. A multicopper oxidase gene from Candida albicans: cloning, characterization and disruption. Microbiology 1999; 145 (Pt 9): 2415–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Musken M, Di FS, Romling U, Haussler S. A 96-well-plate-based optical method for the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation and its application to susceptibility testing. Nat Protoc. 2010; 5: 1460–1469. 10.1038/nprot.2010.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Harrison JJ, Stremick CA, Turner RJ, Allan ND, Olson ME, Ceri H. Microtiter susceptibility testing of microbes growing on peg lids: a miniaturized biofilm model for high-throughput screening. Nat Protoc. 2010; 5: 1236–1254. 10.1038/nprot.2010.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen P, Abercrombie JJ, Jeffrey NR, Leung KP. An improved medium for growing Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. J Microbiol Methods. 2012; 90: 115–118. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Efthimiadis A, Spanevello A, Hamid Q, Kelly MM, Linden M, Louis R, et al. Methods of sputum processing for cell counts, immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridisation. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2002; 37: 19s–23s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peeters E, Nelis HJ, Coenye T. Comparison of multiple methods for quantification of microbial biofilms grown in microtiter plates. J Microbiol Methods. 2008; 72: 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Douglas LJ. Candida biofilms and their role in infection. Trends Microbiol. 2003; 11: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. El-Azizi MA, Starks SE, Khardori N. Interactions of Candida albicans with other Candida spp. and bacteria in the biofilms. J Appl Microbiol. 2004; 96: 1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999; 284: 1318–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramage G, Bachmann S, Patterson TF, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. Investigation of multidrug efflux pumps in relation to fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002; 49: 973–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramage G, Vandewalle K, Bachmann SP, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. In vitro pharmacodynamic properties of three antifungal agents against preformed Candida albicans biofilms determined by time-kill studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002; 46: 3634–3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ramage G, Wickes BL, Lopez-Ribot JL. Biofilms of Candida albicans and their associated resistance to antifungal agents. Am Clin Lab. 2001; 20: 42–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lewis K. Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001; 45: 999–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Klotz SA, Chasin BS, Powell B, Gaur NK, Lipke PN. Polymicrobial bloodstream infections involving Candida species: analysis of patients and review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007; 59: 401–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cassat JE, Lee CY, Smeltzer MS. Investigation of biofilm formation in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. Methods Mol Biol. 2007; 391: 127–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Harriott MM, Noverr MC. Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus form polymicrobial biofilms: effects on antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009; 53: 3914–3922. 10.1128/AAC.00657-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carlson E, Johnson G. Protection by Candida albicans of Staphylococcus aureus in the establishment of dual infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1985; 50: 655–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peters BM, Ovchinnikova ES, Krom BP, Schlecht LM, Zhou H, Hoyer LL, et al. Staphylococcus aureus adherence to Candida albicans hyphae is mediated by the hyphal adhesin Als3p. Microbiology 2012; 158: 2975–2986. 10.1099/mic.0.062109-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ovchinnikova ES, Krom BP, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC. Evaluation of adhesion forces of Staphylococcus aureus along the length of Candida albicans hyphae. BMC Microbiol. 2012; 12: 281 10.1186/1471-2180-12-281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Peters BM, Jabra-Rizk MA, Scheper MA, Leid JG, Costerton JW, Shirtliff ME. Microbial interactions and differential protein expression in Staphylococcus aureus-Candida albicans dual-species biofilms. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010; 59: 493–503. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00710.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kaneko M, Togashi N, Hamashima H, Hirohara M, Inoue Y. Effect of farnesol on mevalonate pathway of Staphylococcus aureus. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2011; 64: 547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tammer I, Reuner J, Hartig R, Geginat G. Induction of Candida albicans biofilm formation on silver-coated vascular grafts. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014; 69: 1282–1285. 10.1093/jac/dkt521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kaplan JB, Jabbouri S, Sadovskaya I. Extracellular DNA-dependent biofilm formation by Staphylococcus epidermidis RP62A in response to subminimal inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics. Res Microbiol. 2011; 162: 535–541. 10.1016/j.resmic.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaplan JB. Antibiotic-induced biofilm formation. Int J Artif Organs. 2011; 34: 737–751. 10.5301/ijao.5000027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kuhn DM, George T, Chandra J, Mukherjee PK, Ghannoum MA. Antifungal susceptibility of Candida biofilms: unique efficacy of amphotericin B lipid formulations and echinocandins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002; 46: 1773–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hornby JM, Nickerson KW. Enhanced production of farnesol by Candida albicans treated with four azoles. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004; 48: 2305–2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Takeuchi K, Kato S, Amagase K. Prostaglandin EP receptors involved in modulating gastrointestinal mucosal integrity. J Pharmacol Sci. 2010; 114: 248–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bozyk PD, Moore BB. Prostaglandin E2 and the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011; 45: 445–452. 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0025RT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Harmon GS, Dumlao DS, Ng DT, Barrett KE, Dennis EA, Dong H, et al. Pharmacological correction of a defect in PPAR-gamma signaling ameliorates disease severity in Cftr-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2010; 16: 313–318. 10.1038/nm.2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boucher RC. Airway surface dehydration in cystic fibrosis: pathogenesis and therapy. Annu Rev Med. 2007; 58: 157–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lucidi V, Ciabattoni G, Bella S, Barnes PJ, Montuschi P. Exhaled 8-isoprostane and prostaglandin E(2) in patients with stable and unstable cystic fibrosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 45: 913–919. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rigas B, Korenberg JR, Merrill WW, Levine L. Prostaglandins E2 and E2 alpha are elevated in saliva of cystic fibrosis patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989; 84: 1408–1412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Noverr MC, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. Production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes by pathogenic fungi. Infect Immun. 2002; 70: 400–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Alem MA, Douglas LJ. Prostaglandin production during growth of Candida albicans biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 2005; 54: 1001–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wachtler B, Wilson D, Haedicke K, Dalle F, Hube B. From attachment to damage: defined genes of Candida albicans mediate adhesion, invasion and damage during interaction with oral epithelial cells. PLoS One 2011; 6: e17046 10.1371/journal.pone.0017046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wachtler B, Citiulo F, Jablonowski N, Forster S, Dalle F, Schaller M, et al. Candida albicans-epithelial interactions: dissecting the roles of active penetration, induced endocytosis and host factors on the infection process. PLoS One 2012; 7: e36952 10.1371/journal.pone.0036952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fernandez-Arenas E, Bleck CK, Nombela C, Gil C, Griffiths G, Diez-Orejas R. Candida albicans actively modulates intracellular membrane trafficking in mouse macrophage phagosomes. Cell Microbiol. 2009; 11: 560–589. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01274.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aronoff DM, Canetti C, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits alveolar macrophage phagocytosis through an E-prostanoid 2 receptor-mediated increase in intracellular cyclic AMP. J Immunol. 2004; 173: 559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Roux D, Gaudry S, Khoy-Ear L, Aloulou M, Phillips-Houlbracq M, Bex J, et al. Airway fungal colonization compromises the immune system allowing bacterial pneumonia to prevail. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41: e191–e199. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a25d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Roux D, Gaudry S, Dreyfuss D, El-Benna J, de Prost N, Denamur E, et al. Candida albicans impairs macrophage function and facilitates Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia in rat. Crit Care Med. 2009; 37: 1062–1067. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31819629d2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bowman CC, Bost KL. Cyclooxygenase-2-mediated prostaglandin E2 production in mesenteric lymph nodes and in cultured macrophages and dendritic cells after infection with Salmonella. J Immunol. 2004; 172: 2469–2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ejima K, Layne MD, Carvajal IM, Kritek PA, Baron RM, Chen YH, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase-2-deficient mice are resistant to endotoxin-induced inflammation and death. FASEB J. 2003; 17: 1325–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sadikot RT, Zeng H, Azim AC, Joo M, Dey SK, Breyer RM, et al. Bacterial clearance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is enhanced by the inhibition of COX-2. Eur J Immunol. 2007; 37: 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang Y, Xu XL. Bacterial peptidoglycan-derived molecules activate Candida albicans hyphal growth. Commun Integr Biol. 2008; 1: 137–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Xu XL, Lee RTH, Fang HM, Wang YM, Li R, Zou H, et al. Bacterial peptidoglycan triggers Candida albicans hyphal growth by directly activating the adenylyl cyclase Cyr1p. Cell Host & Microbe 2008; 4: 28–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

(TIF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.