Abstract

Collecting phenotypic data necessary for genetic analyses of neuropsychiatric disorders is time consuming and costly. Development of web-based phenotype assessments would greatly improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of genetic research. However, evaluating the reliability of this approach compared to standard, in-depth clinical interviews is essential. The current study replicates and extends a preliminary report on the utility of a web-based screen for Tourette Syndrome (TS) and common comorbid diagnoses (obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)). A subset of individuals who completed a web-based phenotyping assessment for a TS genetic study was invited to participate in semi-structured diagnostic clinical interviews. The data from these interviews were used to determine participants’ diagnostic status for TS, OCD, and ADHD using best estimate procedures, which then served as the gold standard to compare diagnoses assigned using web-based screen data. The results show high rates of agreement for TS. Kappas for OCD and ADHD diagnoses were also high and together demonstrate the utility of this self-report data in comparison previous diagnoses from clinicians and dimensional assessment methods.

Keywords: Tourette Syndrome, Obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, web-based assessment

1. Introduction

Tourette Syndrome (TS) is a childhood-onset neuropsychiatric disorder marked by the occurrence of multiple motor tics and at least one phonic tic for a period of more than a year (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The reported prevalence of TS is 0.3–0.7% internationally (Scharf et al., 2014) and affects males more frequently than females at a rate of 3 or 4 to 1 (Robertson, 2008; Scharf and Pauls, 2008). TS symptom severity generally waxes and wanes, typically beginning between ages 5 and 7, intensifying between ages 10 and 12, and diminishing in strength thereafter (Conelea et al., 2014). While many individuals experience a marked decrease in tic symptoms in adulthood, for others, symptoms persist (Ludolph et al., 2012; Tamara, 2013).

The disease burden of TS is high. In a recent study, adults with TS reported lower quality of life (QOL) than was reported by “healthy” adults and scored significantly higher on scales of depression and anxiety than the general population (Conelea et al., 2014). This may be due in part to the high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, predominantly obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which occur at rates of 30–50% and 30–90% respectively (Bloch et al., 2006; Coffey et al., 2000; Freeman, 2007; Hirschtritt et al., 2015).

Etiological studies have demonstrated a complex relationship between TS, OCD, and ADHD, both phenotypically and genetically (Davis et al., 2013; Gunther et al., 2012; Mathews and Grados, 2011; McGrath et al., 2014; O’Rourke et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2015). Additionally, recent evidence suggests that TS, OCD, and ADHD are polygenic, meaning many genes contribute jointly to their symptom expression (Davis et al., 2013; Gratten et al., 2014). Therefore, studies attempting to identify specific, genome-wide significant TS-related genes necessitate large sample sizes, typically in the range of thousands to tens of thousands (O’Rourke et al., 2009; Scharf et al., 2013). As with other neuropsychiatric disorders, sample collection has been a rate-limiting factor in TS genetic research. Traditionally, recruitment of appropriate participants has taken place through TS specialty clinics, which tend to be located in large urban areas and therefore have a limited referral base. In addition, phenotypic data have historically been obtained through lengthy structured interviews, creating a substantial participant burden at a high cost of time and resources.

To address these obstacles, we have developed a web-based phenotyping measure, the Tourette Internet-implemented Questionnaire, (TIQue) (Egan et al., 2012) for online recruitment of participants throughout the United States. Not only does this measure allow individuals who do not live near a TS specialty clinic to participate, it also enables efficient, cost-effective collection of TS phenotype data, including tic symptoms, severity, and information about comorbid conditions. This information is entered directly by the participants into the TIQue through a secure web-site.

Following the initial phase of web-based recruitment for an ongoing TS genetic study, the authors reported on the effectiveness of the TIQue, showing that 631 participants completed the online questionnaires and also provided a DNA sample compared to only 238 TS participants recruited through a standard methods at six TS specialty clinics over the same time period (Egan et al., 2012). The authors also reported a concordance rate of 100% between eligibility criteria for genetic studies of TS determined by the web-based screen and eligibility based on in-depth diagnostic interviews conducted in a subset of participants.

Since this initial report, over 1,400 additional individuals have completed the TIQue; thus, we now have the ability to expand our previous validation of the TIQue for TS and to extend analyses to OCD and ADHD. Therefore, the goals of this study were 1) to examine the concordance rates for TS diagnoses between the TIQue and gold standard diagnoses in a larger, potentially more heterogeneous sample, and 2) to analyze the reliability of OCD and ADHD diagnoses provided by the TIQue, and 3) to identify the best method of assigning DSM-IV diagnoses using TIQue variables.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedures and Participants

The data used in the current study were part of a larger data collection effort for ongoing TS genetic studies (Egan et al., 2012; Scharf et al., 2013). Detailed procedures, including the development and implementation of the TIQue, have been described in Egan and colleagues (2012). Current analyses consist of TIQue data collected between April 2010 and January 2014, and include the preliminary sample evaluated in the initial report. In addition to letters emailed and mailed to Tourette Syndrome Association (TSA) members, patients identified as likely having TS were referred to the website by clinicians at multiple collaborating sites. Individuals accessed the TIQue through an open link. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at each site. Participants, or their parents, in the case of minors, provided informed consent before completing the TIQue.

As the main study aimed to collect TS-affected individuals for genetic research, exclusion criteria included the following: known intellectual disability, seizure disorder or epilepsy, other known genetic or neurological conditions, individuals whose family members had previously completed the TIQue, or completion of a TS genetic study in the previous five years by an individual or family member. Since its launch, a total of 3251 individuals initiated the TIQue and 2643 individuals completed it (81.3%). A random sample of those with complete data (n = 614) was invited to undergo in-depth clinical interviews for the current validation study; 257 (41.9%) agreed.

A semi-structured clinical interview (the TSAICG Tic and Comorbid Symptom (TICS) inventory described in section 2.2.2) was conducted in-person or using an online video-calling service to enable observation and documentation of tics, or by telephone when other options were not available. Interviews were administered by a PhD level interviewer or a senior medical student with clinical research experience (CI, CE, ME, MH), specifically trained in TS and related disorders and in the standardized administration and scoring of the TICS inventory. Additionally, interviewers were asked to provide narrative information documenting their observations of psychiatric symptoms.

2.2 Assessments

2.2.1 The TIQue

The TIQue (Egan et al., 2012) is a web-based screen and assessment tool adapted from the comprehensive diagnostic Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics (TSAICG) TICS Inventory (Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics, 2007). The TIQue collects demographic, medical history and disorder-specific symptom information corresponding to the diagnoses of TS, OCD and ADHD. The TIQue also asks participants whether they had been previously diagnosed with TS, OCD, or ADHD by a clinician.

2.2.1.1

The Tic section of the TIQue is comprised of a checklist of tic symptoms grouped into 12 categories of simple and complex motor tics and 6 categories of simple and complex phonic tics. Each category contains examples of several related tics. For example, the Eye Movements category includes eye blinking, squinting, eye rolling, or opening eyes wide briefly, looking surprised or quizzical, looking to one side for a brief period of time. Respondents indicated their lifetime experience of each tic category (i.e., whether the tics occurred in the past month, sometime in the past, or never). Subsequent questions assessed the participant’s age at tic onset, duration of tics, and characteristics such as suppressibility, premonitory urges, and fluctuating severity and course.

2.2.1.2

The TIQue OCD symptom checklist is based on the Florida Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (FOCI; Storch et al., 2007) and includes 10 obsessions and 10 compulsions that participants rated for lifetime occurrence (i.e., current, past, never). Severity ratings for time, distress, control, avoidance and interference for both current and worst ever periods were also collected. These dimensions were rated on the 5 point scale adapted from the Yale Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale ratings (Goodman et al., 1989), generally corresponding to “0-none”, “1-mild”, “2-moderate”, “3-severe” and “4-extreme”.

2.2.1.3

The ADHD section was adapted from the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire (SNAP-IV; Swanson et al., 1992) and consists of 10 inattentive and 10 hyperactive-impulsive symptoms (e.g., “often had difficulty sustaining attention in tasks or play activities”). ADHD symptoms were rated on a 4 point scale, depending on how frequently they occurred as a child, corresponding to “0-not at all” to “3-very much”. Information on age of symptom onset, interference and impairment were also collected.

2.2.1.4

Although TIQue data can be used in many ways (e.g., to examine number of tics, severity of OCD symptoms, etc), the aim of the current study was to assess the reliability of categorical TS, OCD, and ADHD diagnoses in relation to diagnoses assigned using the current gold standard (see description in 2.3). We thus developed algorithms using the TIQue responses to assign diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria for TS, OCD, and ADHD.

In order to determine lifetime TS diagnoses, past and current responses were combined. As multiple tics were contained within each category, a TS diagnosis was assigned if a participant endorsed at least one category of motor tics and one of phonic tics, tic onset before 18, and duration of tics for at least one year.

To meet criteria for an OCD diagnosis, a participant had to endorse a minimum of either moderate time (>1 hour per day) spent on obsessions or compulsions with some reported distress or interference, or at least moderate interference or distress caused by these symptoms. The number of obsessive compulsive symptoms needed to maximize the reliability of the OCD screen was explored statistically as subsequently described. If no symptoms were endorsed, severity was set to “none”.

A diagnosis of ADHD was assigned if participants endorsed at least 6 inattentive or hyperactive symptoms, with age of onset before 7 and impairment across at least two domains. If a participant endorsed interference with daily life at school as well as difficulties at school, this was considered impairment in only one domain. If no symptoms were endorsed, interference and impairment items were set to “none”.

2.2.2. TSAICG Tic and Comorbid Symptom Inventory (TICS; Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics, 2007)

The TICS Inventory was used by trained clinicians, as described above, to conduct clinical interviews. The TICS Inventory is a semi-structured diagnostic interview originally developed by the TSAICG for ongoing genetic studies of TS. Previous psychometric evaluations of an earlier version of the TICS Inventory demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability and validity based on comparisons with expert clinician ratings (Leckman et al., 1993; Pauls et al., 1995). The current version of the TICS Inventory includes a demographics section, the diagnostic assessments of tics, OCD, ADHD, and grooming disorders, a medication checklist and prenatal, perinatal and early developmental history. Both child and adult versions of the interview are available. Only the tic, OCD, and ADHD sections (described below) were used for the current study. For all symptoms described in the following sections, clinicians were asked to rate the likelihood that the endorsed symptoms were actual symptoms of the respective disorders on a scale of 0 (not likely to be a real symptom) to 3 (definitely a real symptom).

The tic section of the TICS Inventory is comprised of 62 specific motor tics (e.g., rolling of eyes to one side) and 24 specific phonic/vocal tics (e.g., coughing), some of which are derived from the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS; Leckman et al., 1989). Each tic symptom is rated on lifetime occurrence (i.e., past week, past 6 months, ever, or never). Interviewers also rated whether tics were observed or were based on historical report only, and whether they were simple or complex. The severity assessment for current and worst ever periods for motor and phonic tics is based on the severity items from the YGTSS (i.e., number, frequency, intensity, complexity, impairment and interference). Moreover, age of onset of first tics, age at worst ever period, and diagnostic and treatment history were also collected.

The OCD assessment in the TICS Inventory consists of 47 compulsive behaviors (e.g., Do you have excessive or ritualized hand washing?) and 61 obsessive symptoms (e.g., Do you fear that you might harm other people?) that are rated using the same lifetime occurrence criteria as in the tic assessment. The OCD checklist is followed by severity ratings corresponding to those in the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS; Goodman et al., 1989), separately evaluating severity of obsessions and compulsions and also current and worst ever periods. Using the same 5-point scoring as the YBOCS, obsessive and compulsive symptoms are rated in terms of time, interference, distress, resistance and control. Similar to the tic assessment, information on age at symptom onset and at worst ever period as well as diagnostic and treatment information are also gathered.

The ADHD section is identical to the ADHD section of the TIQue, with the addition of questions about medication use for ADHD and a narrative section for the clinician to describe the ADHD symptoms and their functional impact.

2.3 Best estimate procedure

A best estimate procedure using all available clinical information was used to assign clinical diagnoses from the in-depth interviews against which the TIQue was validated. (Leckman et al., 1982) Using a web-based process developed by the TSAICG (McMahon et al., 2006), best estimators (clinicians with expertise in TS who did not conduct the interviews) reviewed electronic copies of participants’ responses to the TICS inventory and any interviewer notes, and assigned diagnoses for TS, chronic motor or vocal tic disorder (CMVT), tic disorder not otherwise specified (TD NOS), OCD, subclinical OCD, ADHD, and ADHD NOS using criteria based on the DSM-IV (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Best estimate (BE) diagnostic criteria

| Diagnosis | Criteria |

|---|---|

| TS | At least 2 motor tics and 1 phonic tic endorsed, tics have occurred for at least 1 year, and age of onset prior to 18 |

| Tic disorder NOS | At least 2 motor tics and 1 phonic tic endorsed, tics have occurred for at least 1 year, age of onset after 18 |

| OCD | Symptoms endorsed occur for: ≥ 1 hour AND (distress ≥ mild OR interference ≥ mild) OR < 1 hour AND (distress ≥ moderate OR interference ≥ moderate) |

| OCD subclinical | Symptoms endorsed occur for < 1 hour or distress = mild AND/OR interference = mild |

| ADHD | 6 inattentive OR 6 hyperactive symptoms endorsed Age onset before 7 Impairment present in at least 3 settings |

| ADHD NOS | Meets symptom & impairment criteria, age of onset 7–13yo OR Current symptoms don’t meet full criteria and unclear whether criteria have previously been met |

Best estimators gave a rating of “not present”, “probable” or “definite” for each lifetime diagnosis, age of onset of each disorder and an indication of whether the individual met diagnostic criteria at the time of the interview (current vs. no longer present). A diagnosis was coded as “probable” if the full criteria were not quite met but the overall information included in the chart suggested that the individual likely met criteria. For example, ADHD inattentive subtype would be coded as “probable” if the individual met impairment and age of onset criteria but endorsed only 5 inattentive symptoms. Only one best estimate was conducted initially. If all diagnoses were assigned either “not present” or met threshold criteria for definite TS, OCD, and ADHD, no second rater was assigned. If any of the TS, OCD or ADHD diagnoses were rated as “probable” or “unable to code” or if any rating other than “not present” was given for CMVTD, TD NOS, subclinical OCD or ADHD NOS, a second best estimator was assigned. Discrepancies were identified and discussed until a consensus was reached.

2.4 Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted in SPSS version 19. Descriptive statistics were used to compare the subsample that completed clinical interviews to those who did not. For the purposes of the analyses, “probable” and “definite” BE diagnoses were collapsed into one category.

For TS diagnoses, we examined the agreement between a best estimate diagnosis of TS and whether an individual reported a previous TS diagnosis by a clinician as well as whether an individual met criteria for TS based on the TIQue TS items (we could not analyze kappa for TS diagnoses because individuals unaffected by TS were not actively recruited). For OCD and ADHD, Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, 1960) was used to examine the agreement on diagnostic status using best estimate diagnoses as the gold standard and various criteria from the TIQue OCD and ADHD sections, including whether an individual reported a previous OCD or ADHD diagnosis by a clinician. Additional kappas were calculated to examine whether excluding certain information from the TIQue changed diagnostic agreement with BE data. For example, in the OCD analyses, TIQue diagnostic status was determined using different symptom endorsement cut-offs (i.e., one symptom endorsed plus severity criteria met, two symptoms endorsed plus severity criteria met, etc.); similar analyses were conducted for ADHD. Kappas were interpreted based on standard criteria (Landis and Koch, 1977): 0.0–0.2 slight, 0.21–0.4 fair, 0.41–0.6 moderate, 0.61–0.8 substantial, 0.81–1.0 almost perfect.

Finally, ROC curves were plotted to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the web-based quantitative OCD severity and ADHD symptom scores using the best estimate diagnostic status as the gold standard; the non-parametric method was used to estimate the area under the curve (AUC). As explained above, the TIQue OCD and ADHD items were adapted from the FOCI and SNAP, respectively; these were developed as continuous measures that employ cut-off scores to determine diagnostic status. Thus, we were able to compare the performance of the TIQue data employed in algorithms based on DSM-IV diagnoses versus use as continuous measures of symptom severity.

3. Results

3.1 Sample Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive data for the total sample and the validation subsample appear in Table 2. Compared to those not asked to complete the clinical interview, those included in the validation subsample were slightly older but did not significantly differ with regard to sex, ethnicity, or race. Using the gold standard best estimate (BE) diagnostic procedure 249 (96.9%) of the 257 participants in the validation sample were assigned a TS diagnosis, 148 (57.6%) had an OCD diagnosis, and 99 (38.5%) had an ADHD diagnosis. Of those with ADHD, twenty-five individuals (25.3%) were given an ADHD inattentive type diagnosis, 9 (9.1%) had an ADHD hyperactive-compulsive subtype diagnosis, and 65 (65.6%) had an ADHD combined subtype diagnosis.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for total sample and validation subsample.

| Total Sample (n = 2363) | Validation Subsample (n = 257) | Not included in validation (n = 2106) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t (df) | p | |

| Age | 23.94 | 16.28 | 28.34 | 17.39 | 23.40 | 16.06 | 4.34 (311.64) | ≤ .001 |

| f | % | f | % | χ2 (df) | ||||

| Male | 1613 | 68.3 | 182 | 70.8 | 1431 | 67.9 | .87 (1) | .35 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Hispanic | 163 | 6.9 | 13 | 5.1 | 150 | 7.1 | 1.45 (1)a | .23 |

| Non-Hispanic | 2189 | 92.6 | 241 | 93.8 | 1948 | 92.5 | ||

| Not reported | 11 | .5 | 3 | 1.2 | 8 | .4 | ||

| Race | ||||||||

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 | .1 | 0 | 2 | .1 | .013 (1) a | .91 | |

| Asian | 24 | 1.0 | 5 | 1.9 | 19 | .9 | ||

| Black or African American | 18 | .8 | 1 | .4 | 17 | .8 | ||

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 | .1 | 0 | 3 | .1 | |||

| White or Caucasian | 2089 | 88.4 | 229 | 89.1 | 1860 | 88.3 | ||

| Multiple | 185 | 7.8 | 20 | 7.8 | 165 | 7.8 | ||

| Not reported | 42 | 1.8 | 2 | .8 | 40 | 1.9 | ||

Due to low frequencies, categories were collapsed into Hispanic versus Non-Hispanic and White versus other. “Not reported” was considered missing.

3.2 Agreement between best estimate TS diagnosis and TS clinician diagnosis or TIQue derived TS diagnosis

The concordance between a previous TS diagnosis from a clinician and the best estimate diagnosis was 87.9%. Seven of the discordant individuals had previously been diagnosed by a clinician but were not given a TS diagnosis by best estimators. Twenty-four had not previously received a TS diagnosis from a clinician but were given a TS diagnosis by best estimators.

The rate of concordance between the TIQue diagnostic criteria and the best estimate diagnosis was 91.3%. Five individuals were excluded because they were missing age of onset information on the TIQue (total available n=252). There was one false positive; this individual met TIQue criteria but was assigned tic disorder NOS by best estimates. There were 21 false negatives (given TS diagnosis by best estimators but did not meet TIQue criteria): twelve did not endorse any phonic tics, three reported age of onset after 18 and six reported tic duration as less than one year on the TIQue.

3.3 Reliability of OCD clinician diagnosis and TIQue derived OCD diagnosis

Thirty-nine participants were missing OCD data (two missing best estimate data, one missing all TIQue OCD symptoms and severity data, and 36 missing TIQue OCD severity data) and, thus were excluded from reliability analyses (total available n = 218). Kappa statistics were used to compare best estimate OCD diagnoses to 1) OCD diagnosis by a clinician and 2) different thresholds for the number of TIQue symptom items endorsed plus the severity criterion. Kappas and corresponding rates of sensitivity, specificity, and other predictive values appear in Table 3.

Table 3.

Reliability data for TIQue OCD diagnosis compared to BE OCD diagnosis

| Kappa | SE | p | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | MR | CCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed by cliniciana | 0.54 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 71.2 | 84.5 | 86.8 | 67.2 | 23.3 | 76.7 |

| 1 OCD symptom & severity | 0.60 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 91.1 | 66.3 | 81.5 | 82.1 | 18.3 | 81.7 |

| 2 OCD symptoms & severity | 0.61 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 90.4 | 68.7 | 82.4 | 81.4 | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| 3 OCD symptoms & severity | 0.62 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 86.7 | 74.7 | 84.8 | 77.5 | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| 4 OCD symptoms & severity | 0.63 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 83.7 | 79.5 | 86.9 | 75.0 | 17.9 | 82.1 |

| 5 OCD symptoms & severity | 0.63 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 77.0 | 89.2 | 92.0 | 70.5 | 18.3 | 81.7 |

| 6 OCD symptoms & severity | 0.58 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 71.9 | 90.4 | 92.4 | 66.4 | 21.1 | 78.9 |

Abbreviations: Se=sensitivity, Sp=specificity, PPV=positive predictive value, NPV = negative predictive value, MR=misclassification rate, CCR = correct classification rate

n = 236 for this analysis

Of the various diagnostic definitions in Table 3, requirement of four endorsed obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) as well as severity criteria on the TIQue performed optimally. Although requiring a four OCS and a five OCS threshold both resulted in similarly high kappas (.63), the four symptom cut-off had a better balance of sensitivity (83.7%) and specificity (79.5%). Thus, a four symptom criterion was used to further examine the discrepancies between diagnoses based on the TIQue and those derived from best estimates.

Meeting severity criteria and endorsing at least four OCS resulted in 17 false positives and 22 false negatives (Table 3). Of the 17 false positives, best estimators gave seven individuals subclinical OCD diagnoses and determined that six individuals endorsed some OCS but did not meet time or impairment criteria. For one participant who endorsed OCS (but denied time, distress or impairment), the notes stated that the interviewer believed the reported symptoms were explained better by a different diagnosis (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder). For another, the notes stated that the endorsed symptoms were “not problematic.”

The TIQue data for the 22 false negatives showed that 12 did not meet severity criteria, nine reported only 2–3 OCS, and one endorsed only one OCS. However, these individuals reported symptoms of sufficient severity during the clinical interview to be assigned a best estimate OCD diagnosis.

In order to examine whether reliability would be improved if the severity criteria was less strict, additional kappas were calculated 1) by lowering the required severity threshold (i.e., endorsed at least mild severity), 2) by comparing TIQue OCD diagnoses to best estimate diagnoses where OCD and OCD subclinical categories were collapsed, and 3) by considering “probable” and “definite” BE diagnoses separately. However, all of these resulted in lower kappas and are therefore not reported.

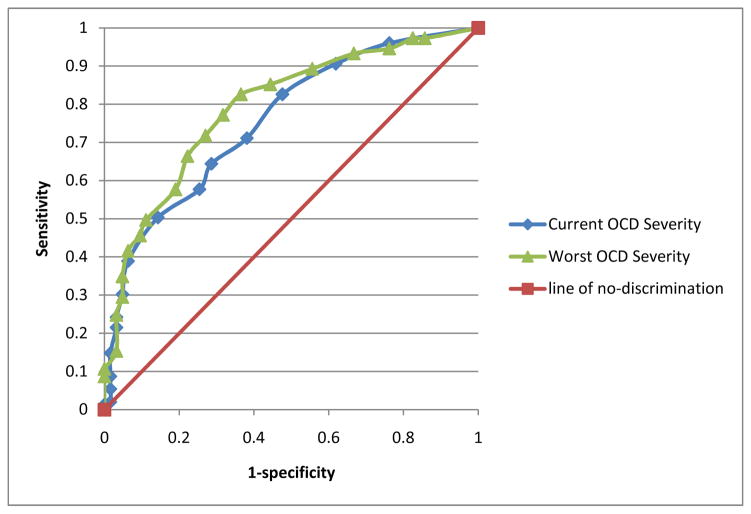

3.4 Sensitivity and Specificity of TIQue OCD total severity scores

The ROC curve for the OCD severity items scored as a quantitative scale was also examined (see Figure 1). Scaled scores were calculated separately for current and worst ever TIQue severity items and compared to best estimate OCD diagnoses. This resulted in a fair AUC (Current: .76, CI = .72–.80, p ≤ .001; Worst ever: .79, CI = .76–.82, p ≤ .001). However, sensitivity and specificity data did not point to an obvious cut-off score that optimally balanced rates of false positives and false negatives (see Table 4).

Figure 1.

Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis of TIQue OCD severity score

Table 4.

Sensitivity and 1 - Specificity rates for TIQue OCD severity scores

| Severity Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | 1 - Specificity | Correct Classification Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 0.5 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.75 |

| 1.5 | 0.91 | 0.62 | 0.75 | |

| 2.5 | 0.83 | 0.48 | 0.74 | |

| 3.5 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.68 | |

| 4.5 | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.67 | |

| 5.5 | 0.58 | 0.25 | 0.63 | |

| 6.5 | 0.50 | 0.14 | 0.61 | |

| 7.5 | 0.39 | 0.06 | 0.55 | |

| 8.5 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.50 | |

| 9.5 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 0.46 | |

| 10.5 | 0.22 | 0.03 | 0.44 | |

| 11.5 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.40 | |

| 12.5 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.35 | |

| 13.5 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.33 | |

| 14.5 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.31 | |

| 16 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.31 | |

| 18.5 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.30 | |

| Worst | 0.5 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.73 |

| 1.5 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.74 | |

| 2.5 | 0.95 | 0.76 | 0.74 | |

| 3.5 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.75 | |

| 4.5 | 0.89 | 0.56 | 0.76 | |

| 5.5 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.76 | |

| 6.5 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.77 | |

| 7.5 | 0.77 | 0.32 | 0.75 | |

| 8.5 | 0.72 | 0.27 | 0.72 | |

| 9.5 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.70 | |

| 10.5 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.65 | |

| 11.5 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.61 | |

| 12.5 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.59 | |

| 13.5 | 0.42 | 0.06 | 0.57 | |

| 14.5 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.53 | |

| 15.5 | 0.30 | 0.05 | 0.49 | |

| 16.5 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 0.46 | |

| 17.5 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.40 | |

| 18.5 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.37 | |

| 19.5 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.36 |

3.5 Reliability of ADHD clinician diagnosis and TIQue ADHD derived diagnosis

Five cases were missing all best estimate ADHD data and two were missing ADHD-inattentive data. Regarding TIQue data, one case was missing all ADHD data and 45 were missing age of onset data. Thus, the number of cases included in reliability analyses for ADHD varied based on the criterion used (n ranged from 204 to 249). Kappas and corresponding rates are reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reliability data for TIQue ADHD diagnosis

| Kappa | SE | p | Se | Sp | PPV | NPV | MR | CCR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compared to BE of ADHD Any subtype | |||||||||

| Diagnosed by clinicianc | 0.51 | 0.06 | <0.001 | 64.6 | 85.1 | 74.7 | 77.9 | 23.2 | 76.8 |

| Compared to BE of ADHD-inattentive | |||||||||

| ADHD-inattention a | 0.36 | 0.12 | <0.001 | 31.6 | 97.3 | 54.5 | 93.3 | 8.8 | 91.2 |

| Compared to BE of ADHD-hyperactive | |||||||||

| ADHD-hyper b | 0.35 | 0.14 | <0.001 | 44.4 | 95.9 | 33.3 | 97.4 | 6.3 | 93.7 |

| Compared to BE of ADHD-combined | |||||||||

| ADHD-combined b | 0.56 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 55.8 | 94.8 | 78.4 | 86.4 | 15.0 | 85.0 |

| Compared to BE of ADHD Any subtype | |||||||||

| ADHD Any subtypea | 0.69 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 68.8 | 96.8 | 93.2 | 82.8 | 14.2 | 85.8 |

| ADHD Any sxs & agea | 0.71 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 72.5 | 96.0 | 92.1 | 84.4 | 13.2 | 86.8 |

| ADHD Any sxs & impaird | 0.64 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 75.2 | 87.8 | 80.9 | 83.9 | 17.3 | 82.7 |

| ADHD Any sxs d | 0.68 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 82.2 | 86.5 | 80.6 | 87.7 | 15.3 | 84.7 |

| ADHD Any 5 symptomsa | 0.69 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 72.5 | 94.4 | 89.2 | 84.2 | 14.2 | 85.8 |

| ADHD Any 5 sxs & agea | 0.71 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 76.3 | 92.7 | 87.1 | 85.8 | 13.7 | 86.3 |

| ADHD Any 4 symptomsa | 0.69 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 75.0 | 92.7 | 87.0 | 85.2 | 14.2 | 85.8 |

| ADHD Any 4 sxs & agea | 0.69 | 0.05 | <0.001 | 78.8 | 89.5 | 82.9 | 86.7 | 14.7 | 85.3 |

Abbreviations: Se=sensitivity, Sp=specificity, PPV=positive predictive value, NPV = negative predictive value, MR=misclassification rate, CCR = correct classification rate

n = 204

n = 206

n = 237

n = 249

Information regarding ADHD subtype for self-reported clinician diagnoses was not available; therefore, any subtype of ADHD coded by best estimators was compared to ADHD diagnosis by a clinician. The results demonstrate that a past diagnosis by a clinician may be useful in screening for ADHD in a TS population; kappa was in the moderate range (0.51). However, kappas were improved when TIQue diagnostic items were used instead (Table 5).

Regarding the TIQue ADHD diagnoses, the highest kappa for the different ADHD subtypes was for ADHD-combined. Twenty-five percent of the sample had an ADHD-combined diagnosis; kappa comparing TIQue and BE for this subtype was in the moderate range (.56). Rates of inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive subtypes were low (<10% of sample). As a result, kappas for these subtypes were also low (.36 and .35 respectively). In examining the false positives and false negatives, many discrepancies were in regard to subtype (i.e., a participant’s TIQue data indicated he met criteria for ADHD-inattentive but was assigned ADHD-hyperactive by best estimators). For this reason, the remaining analyses did not make a distinction between the subtypes but, rather, looked at the criteria for meeting any subtype of ADHD.

The kappa for the comparison of TIQue ADHD diagnosis to BE ADHD diagnosis was in the substantial range (.69). Of the four false positives, two were given ADHD NOS by best estimators because they endorsed age of onset at 10. Of the 25 false negatives, four did not meet the impairment criteria, ten did not meet the age of onset criteria, two did not meet either age or impairment criteria on the TIQue. Of those that met the TIQue age and impairment criteria, one did not endorse symptoms, two endorsed three symptoms, one endorsed four symptoms, three endorsed five symptoms for either hyperactive or inattentive subtypes.

Reliability was slightly increased and an improved balance between false positives and false negatives was obtained by excluding the impairment criterion (Table 5).

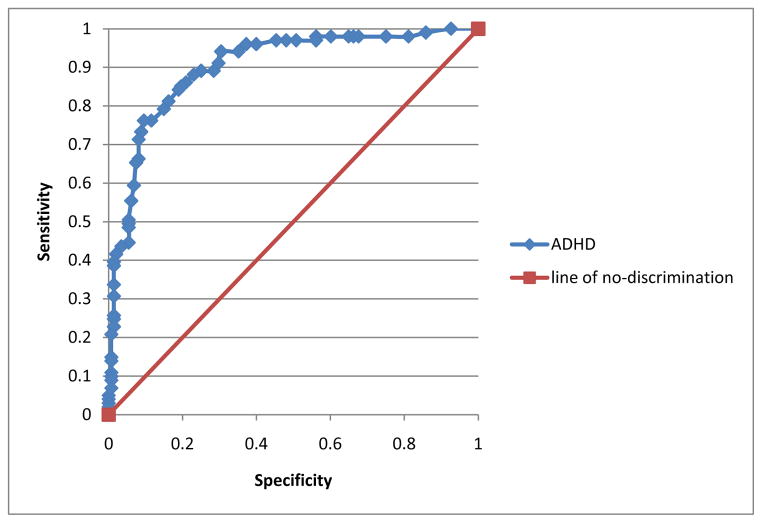

3.7 Sensitivity and Specificity of TIQue ADHD symptoms

The ROC curve of the TIQue ADHD symptom quantitative score was also examined (Figure 2). The total scale score was compared to BE ADHD diagnosis. This resulted in a good AUC (.90, ci = .86–.94, p < .001). Unlike the OCD analyses, we were able to identify an appropriate cutoff to quantify scores for ADHD. Choosing a cutoff of 24.5 appeared to result in an acceptable balance between sensitivity (81% true positives) and specificity (16% false positives; see Table 6).

Figure 2.

Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis of TIQue ADHD symptoms score

Table 6.

Sensitivity and 1-Specificity rates for ADHD TIQue symptoms score

| ADHD Cutoff Score | Sensitivity | 1-Specificity | Correct Classification Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.45 |

| 1.5 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 0.49 |

| 2.5 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 0.51 |

| 3.5 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.55 |

| 4.5 | 0.98 | 0.68 | 0.59 |

| 5.5 | 0.98 | 0.66 | 0.60 |

| 6.5 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.61 |

| 7.5 | 0.98 | 0.60 | 0.63 |

| 8.5 | 0.98 | 0.56 | 0.66 |

| 9.5 | 0.97 | 0.56 | 0.65 |

| 10.5 | 0.97 | 0.51 | 0.69 |

| 11.5 | 0.97 | 0.48 | 0.70 |

| 12.5 | 0.97 | 0.45 | 0.72 |

| 13.5 | 0.96 | 0.40 | 0.75 |

| 14.5 | 0.96 | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| 15.5 | 0.94 | 0.35 | 0.77 |

| 16.5 | 0.94 | 0.30 | 0.80 |

| 17.5 | 0.91 | 0.30 | 0.79 |

| 18.5 | 0.89 | 0.28 | 0.79 |

| 19.5 | 0.89 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| 20.5 | 0.88 | 0.23 | 0.82 |

| 21.5 | 0.86 | 0.21 | 0.82 |

| 22.5 | 0.85 | 0.20 | 0.82 |

| 23.5 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.82 |

| 24.5 | 0.81 | 0.16 | 0.83 |

| 25.5 | 0.79 | 0.15 | 0.83 |

| 26.5 | 0.76 | 0.12 | 0.84 |

| 27.5 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 0.85 |

| 28.5 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.84 |

| 29.5 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.84 |

| 30.5 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.82 |

| 31.5 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.82 |

| 32.5 | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.80 |

| 33.5 | 0.55 | 0.06 | 0.78 |

| 34.5 | 0.51 | 0.05 | 0.77 |

| 36 | 0.50 | 0.05 | 0.76 |

| 37.5 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.76 |

| 38.5 | 0.45 | 0.05 | 0.74 |

| 39.5 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.75 |

| 40.5 | 0.42 | 0.02 | 0.75 |

| 41.5 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.75 |

| 42.5 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| 43.5 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.72 |

| 44.5 | 0.31 | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| 45.5 | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.69 |

| 46.5 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.69 |

| 47.5 | 0.23 | 0.01 | 0.68 |

| 48.5 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.67 |

| 50.0 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.65 |

| 51.5 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.65 |

| 52.5 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| 53.5 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| 54.5 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.63 |

| 55.5 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.62 |

| 56.5 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.61 |

| 57.5 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.61 |

| 58.5 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.61 |

| 59.5 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.60 |

4. Discussion

This study confirms the utility of the TIQue for remote, web-based screening of tic disorders, OCD, and ADHD. The results of the current analyses demonstrated a high level of agreement (91.3%) between the TIQue-derived and best estimate TS diagnoses. Thus, online phenotyping for TS can be effective and reliable, at least for individuals who self-identify as having a tic disorder.

Our data also support the reliability of the TIQue for assessing OCD. The original FOCI, from which our screen was derived, was designed as a self-report measure (Storch et al., 2007) and is available on many OCD related websites. The FOCI has moderate correlation with Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) obsessive, compulsive, and total severity scores (correlations = 0.71 to 0.87) (Storch et al., 2007). However, to our knowledge, the FOCI has not been validated against the current gold standard, an OCD diagnosis obtained by clinician-administered, structured interview. Similarly, the best use of the FOCI questions to assign OCD diagnoses with maximum reliability has not been previously examined. While we did not find the traditional scoring of the FOCI using the severity measure to be optimal for assigning OCD diagnoses in our sample, we were able to create an algorithm, which included the presence of four or more OCD symptoms plus the traditional severity criteria, that had a correct classification rate of 82%, indicating that it is an appropriate alternative to an in-depth clinical interview. While the DSM does not require a specific number of OCS necessary to meet diagnostic criteria, our data indicated that individuals who endorsed only a few OCS on the TIQue typically did not meet full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. This may be because the TIQue does not describe the ego dystonicity that is characteristic of OCS. Adding such a description to the questionnaire to further specify what experiences individuals should consider when reporting symptoms may improve its reliability. This could also affect the number of symptoms needed to have a reliable TIQue derived OCD diagnosis.

As with OCD, we used a previously published instrument in common use for ADHD screening (SNAP-IV), and modified it to fit the project needs. Using DSM-IV derived TIQue criteria rather than a dimensional measure of ADHD symptom items led to much better specificity (categorical TIQue-derived diagnoses had a 3% false positive rate, while the dimensional symptom count criteria had a 16% false positive rate). However, the sensitivity of the dimensional score was much better than the categorical diagnostic criteria (81% and 69% true positive, respectively).

We argue that use of the ADHD portion of the TIQue is likely to be the most effective when our algorithm, based on DSM-IV criteria, is used. This is because the DSM-IV ADHD symptom criteria can be implemented across samples without difficulty, while the appropriate cutoff derived from the quantitative score is likely to change from sample to sample, based on other characteristics (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity, and co-occurring conditions). However, the predictive power of the TIQue ADHD section may also be improved by requiring individuals to respond to the age of onset item, as much of the missing data related to age of onset. Future revisions of the TIQue might also change the way in which this question is asked; the current form asks if symptom onset occurred before age 7, which did not allow us to examine how the TIQue performs when considering the new age of onset criteria (onset before age 12) in DSM-5 (2013). Additionally, exploring different ways to ask about the impairment criterion may be warranted since excluding this criterion slightly improved the reliability of the TIQue data. Excluding the severity criteria is not an optimal solution as there is already concern regarding the potential over-diagnosis of ADHD.

The results comparing clinician diagnoses to best estimate diagnoses were also of interest. Many large, population-based studies rely on clinician-assigned diagnoses (e.g., ICD codes in a health registry database) to identify eligible participants. We were able to examine the effectiveness of clinician-assigned diagnoses in this study, as the TIQue asked participants whether they had previously been given a TS, OCD, or ADHD diagnosis. There was a high rate of agreement between a clinician diagnosis and best estimate diagnosis for TS, OCD and ADHD. However, the appropriateness of using reported clinician-assigned diagnosis rather than direct assessment depends on the study design. For those studies where false positives are of concern but false negatives are not, our data suggests that using clinician diagnoses is an acceptable methodological decision. For example, for OCD and ADHD, rates of false positives were no more than 15%. However, the rates of false negatives using clinician assigned diagnoses were much higher, and the reliability of the TIQue-derived diagnoses for OCD and ADHD showed a substantial improvement over clinician-assigned diagnoses. Thus, if false negatives are of concern in a particular study design, a web-based assessment that asks about specific criteria, such as the TIQue, should be considered.

4.1 Limitations

The primary limitation of this study is generalizability of the current findings to other samples. This research was conducted as part of a larger genetic study and recruitment targeted individuals with TS who were interested in TS related research. For this reason, the vast majority of our participants had TS, precluding reliability analyses for TS diagnoses. Future studies will need to examine the reliability of TS diagnoses using the TIQue in a general sample. In addition, the results of the reliability analyses for OCD and ADHD may not be generalizable beyond a sample of individuals with TS. Although participants were not selected on OCD or ADHD status, both of these disorders are more prevalent in TS samples than in the general population. Future research will need to examine the TIQue’s performance in mental health treatment seeking populations or the general population in order to support the utility of the TIQue more broadly. However, the potential to expand the reach of research to underserved geographical regions and increase the efficiency and ability to study TS in the future is encouraging.

Highlights.

We compared a web-based screen to standard, clinical interviews in a TS sample.

Concordance between TS diagnoses given by the two methods was high.

The web-based screen gave reliable OCD and ADHD diagnoses.

Use of DSM criteria was more useful than quantitative scores to assess OCD and ADHD.

Previous diagnosis by a clinician may also be a useful screening method.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers R01MH096767 (“Refining the Tourette syndrome phenotype across diagnoses to aid gene discovery,” PI: Carol Mathews), U01NS040024 (“A genetic linkage study of GTS,” PI: David Pauls), K23MH085057 (“Translational phenomics and genomics of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome,” PI: Jeremiah Scharf), K02MH00508 (“Genetics of a behavioral disorder: Tourette syndrome,” PI: David Pauls), and R01NS016648 (“A genetic study of GTS, OCD, and ADHD,” PI: David Pauls), and from the Tourette Syndrome Association.

Footnotes

Contributors

Sabrina M. Darrow- best estimation, data analyses, wrote parts of and reviewed and approved manuscript

Cornelia Illmann - data collection, clinical interviews, best estimation, wrote parts of and reviewed and approved manuscript

Caitlin Gauvin- data collection, wrote parts of and reviewed and approved manuscript

Lisa Osiecki-data collection and management, reviewed & approved manuscript

Crystelle A. Egan-clinical interviews, reviewed and approved manuscript

Erica Greenberg- best estimation, reviewed & approved manuscript

Monika Eckfield- clinical interviews, reviewed and approved manuscript

Matthew E. Hirschtritt- clinical interviews, reviewed and approved manuscript

David Pauls- design of original clinical study, best estimation, reviewed & approved manuscript

James Batterson - data collection, reviewed & approved manuscript

Cheston Berlin- data collection, reviewed & approved manuscript

Irene Malaty- data collection, reviewed & approved manuscript

Douglas. Woods- data collection, reviewed & approved manuscript

Jeremiah Scharf- design of original clinical study, design of current study, best estimation, reviewed & approved manuscript

Carol Mathews- design of original clinical study, design of current study, best estimation, wrote parts of, reviewed & approved manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Woods, Pauls, Malaty, Scharf and Mathews have received research support, honoraria and travel support from the TSA. Drs. Malaty, Mathews and Woods are members of the TSA Medical Advisory Board; Dr. Scharf is a member of the TSA Scientific Advisory Board. Dr. Malaty is a participant in the TSA Center of Excellence program. None of the funding agencies for this project (NINDS, NIMH, the Tourette Syndrome Association) had any influence or played any role in a) the design or conduct of the study; b) management, analysis or interpretation of the data; c) preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. Dr. Woods receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Springer Press, and Guilford Press. The other authors do not have potential conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Arlington, VA: 2000. Text Revision ed. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5TM. 5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; Arlington, VA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch MH, Peterson BS, Scahill L, Otka J, Katsovich L, Zhang H, Leckman JF. Adulthood outcome of tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children with Tourette syndrome. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160(1):65–69. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey BJ, Biederman J, Geller DA, Spencer T, Park KS, Shapiro SJ, Garfield SB. The course of Tourette’s disorder: a literature review. Harvard review of psychiatry. 2000;8(4):192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20:37–46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/001316446002000104. [Google Scholar]

- Conelea CA, Busch AM, Catanzaro MA, Budman CL. Tic-related activity restriction as a predictor of emotional functioning and quality of life. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(1):123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LK, Yu D, Keenan CL, Gamazon ER, Konkashbaev AI, Derks EM, Neale BM, Yang J, Lee SH, Evans P, Barr CL, Bellodi L, Benarroch F, Berrio GB, Bienvenu OJ, Bloch MH, Blom RM, Bruun RD, Budman CL, Camarena B, Campbell D, Cappi C, Cardona Silgado JC, Cath DC, Cavallini MC, Chavira DA, Chouinard S, Conti DV, Cook EH, Coric V, Cullen BA, Deforce D, Delorme R, Dion Y, Edlund CK, Egberts K, Falkai P, Fernandez TV, Gallagher PJ, Garrido H, Geller D, Girard SL, Grabe HJ, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Gross-Tsur V, Haddad S, Heiman GA, Hemmings SM, Hounie AG, Illmann C, Jankovic J, Jenike MA, Kennedy JL, King RA, Kremeyer B, Kurlan R, Lanzagorta N, Leboyer M, Leckman JF, Lennertz L, Liu C, Lochner C, Lowe TL, Macciardi F, McCracken JT, McGrath LM, Mesa Restrepo SC, Moessner R, Morgan J, Muller H, Murphy DL, Naarden AL, Ochoa WC, Ophoff RA, Osiecki L, Pakstis AJ, Pato MT, Pato CN, Piacentini J, Pittenger C, Pollak Y, Rauch SL, Renner TJ, Reus VI, Richter MA, Riddle MA, Robertson MM, Romero R, Rosario MC, Rosenberg D, Rouleau GA, Ruhrmann S, Ruiz-Linares A, Sampaio AS, Samuels J, Sandor P, Sheppard B, Singer HS, Smit JH, Stein DJ, Strengman E, Tischfield JA, Valencia Duarte AV, Vallada H, Van Nieuwerburgh F, Veenstra-Vanderweele J, Walitza S, Wang Y, Wendland JR, Westenberg HG, Shugart YY, Miguel EC, McMahon W, Wagner M, Nicolini H, Posthuma D, Hanna GL, Heutink P, Denys D, Arnold PD, Oostra BA, Nestadt G, Freimer NB, Pauls DL, Wray NR, Stewart SE, Mathews CA, Knowles JA, Cox NJ, Scharf JM. Partitioning the heritability of Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder reveals differences in genetic architecture. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(10):e1003864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan CA, Marakovitz SE, O’Rourke JA, Osiecki L, Illmann C, Barton L, McLaughlin E, Proujansky R, Royal J, Cowley H, Rangel-Lugo M, Pauls DL, Scharf JM, Mathews CA. Effectiveness of a web-based protocol for the screening and phenotyping of individuals with Tourette syndrome for genetic studies. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2012;159B(8):987–996. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RD. Tic disorders and ADHD: answers from a world-wide clinical dataset on Tourette syndrome. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16(Suppl 1):15–23. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-1003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, Heninger GR, Charney DS. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):1006–1011. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810110048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratten J, Wray NR, Keller MC, Visscher PM. Large-scale genomics unveils the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(6):782–790. doi: 10.1038/nn.3708. nn.3708 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther J, Tian Y, Stamova B, Lit L, Corbett B, Ander B, Zhan X, Jickling G, Bos-Veneman N, Liu D, Hoekstra P, Sharp F. Catecholamine-related gene expression in blood correlates with tic severity in tourette syndrome. Psychiatry Research. 2012;200(2–3):593–601. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.034. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls D, Dion Y, Grados MA, Illmann C, King R, Sandor P, McMahon WM, Lyon GJ, Cath DC, Kurlan R, Robertson MM, Osiecki L, Scharf JM, Mathews CA Genetics, ftTSAICf. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and etiology of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, Ort SI, Swartz KL, Stevenson J, Cohen DJ. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28(4):566–573. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198907000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodological study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1982;39(8):879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leckman JF, Walker DE, Cohen DJ. Premonitory urges in Tourette’s syndrome. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1993;150(1):98–102. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludolph AG, Roessner V, Munchau A, Muller-Vahl K. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders in childhood, adolescence and adulthood. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(48):821–288. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews CA, Grados MA. Familiality of Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Heritability analysis in a large sib-pair sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2011;50(1):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath LM, Yu D, Marshall C, Davis LK, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Li B, Cappi C, Gerber G, Wolf A, Schroeder FA, Osiecki L, O’Dushlaine C, Kirby A, Illmann C, Haddad S, Gallagher P, Fagerness JA, Barr CL, Bellodi L, Benarroch F, Bienvenu OJ, Black DW, Bloch MH, Bruun RD, Budman CL, Camarena B, Cath DC, Cavallini MC, Chouinard S, Coric V, Cullen B, Delorme R, Denys D, Derks EM, Dion Y, Rosario MC, Eapen V, Evans P, Falkai P, Fernandez TV, Garrido H, Geller D, Grabe HJ, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Gross-Tsur V, Grunblatt E, Heiman GA, Hemmings SM, Herrera LD, Hounie AG, Jankovic J, Kennedy JL, King RA, Kurlan R, Lanzagorta N, Leboyer M, Leckman JF, Lennertz L, Lochner C, Lowe TL, Lyon GJ, Macciardi F, Maier W, McCracken JT, McMahon W, Murphy DL, Naarden AL, Neale BM, Nurmi E, Pakstis AJ, Pato MT, Pato CN, Piacentini J, Pittenger C, Pollak Y, Reus VI, Richter MA, Riddle M, Robertson MM, Rosenberg D, Rouleau GA, Ruhrmann S, Sampaio AS, Samuels J, Sandor P, Sheppard B, Singer HS, Smit JH, Stein DJ, Tischfield JA, Vallada H, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Walitza S, Wang Y, Wendland JR, Shugart YY, Miguel EC, Nicolini H, Oostra BA, Moessner R, Wagner M, Ruiz-Linares A, Heutink P, Nestadt G, Freimer N, Petryshen T, Posthuma D, Jenike MA, Cox NJ, Hanna GL, Brentani H, Scherer SW, Arnold PD, Stewart SE, Mathews CA, Knowles JA, Cook EH, Pauls DL, Wang K, Scharf JM. Copy number variation in obsessive-compulsive disorder and tourette syndrome: a cross-disorder study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(8):910–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.04.022. S0890-8567(14)00404-3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon WM, Illmann CL, McGinn MM, Walkup JT, Mink JW, Hollenbeck PJ. Advances in neurology: Tourette syndrome. Vol. 99. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. Web-Based Consensus Diagnosis for Genetics Studies of Gilles De La Tourette Syndrome; pp. 136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke JA, Scharf JM, Platko J, Stewart SE, Illmann C, Geller DA, King RA, Leckman JF, Pauls DL. The familial association of tourette’s disorder and ADHD: the impact of OCD symptoms. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2011;156B(5):553–560. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke JA, Scharf JM, Yu D, Pauls DL. The genetics of Tourette syndrome: a review. J Psychosom Res. 2009;67(6):533–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Alsobrook JP, Goodman W, Rasmussen S, Leckman JF. A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(1):76–84. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MM. The prevalence and epidemiology of Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Part 1: the epidemiological and prevalence studies. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(5):461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf JM, Miller LL, Gauvin CA, Alabiso J, Mathews CA, Ben-Shlomo Y. Population prevalence of Tourette syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mds.26089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf JM, Pauls DL. Genetics of Tic Disorders. In: Rimoin CJDL, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, editors. Emery and Rimoin’s Principles and Practices of Medical Genetics. 5. Livingstone/Elsevier; 2008. pp. 2737–2754. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf JM, Yu D, Mathews CA, Neale BM, Stewart SE, Fagerness JA, Evans P, Gamazon E, Edlund CK, Service SK, Tikhomirov A, Osiecki L, Illmann C, Pluzhnikov A, Konkashbaev A, Davis LK, Han B, Crane J, Moorjani P, Crenshaw AT, Parkin MA, Reus VI, Lowe TL, Rangel-Lugo M, Chouinard S, Dion Y, Girard S, Cath DC, Smit JH, King RA, Fernandez TV, Leckman JF, Kidd KK, Kidd JR, Pakstis AJ, State MW, Herrera LD, Romero R, Fournier E, Sandor P, Barr CL, Phan N, Gross-Tsur V, Benarroch F, Pollak Y, Budman CL, Bruun RD, Erenberg G, Naarden AL, Lee PC, Weiss N, Kremeyer B, Berrio GB, Campbell DD, Cardona Silgado JC, Ochoa WC, Mesa Restrepo SC, Muller H, Valencia Duarte AV, Lyon GJ, Leppert M, Morgan J, Weiss R, Grados MA, Anderson K, Davarya S, Singer H, Walkup J, Jankovic J, Tischfield JA, Heiman GA, Gilbert DL, Hoekstra PJ, Robertson MM, Kurlan R, Liu C, Gibbs JR, Singleton A, Hardy J, Strengman E, Ophoff RA, Wagner M, Moessner R, Mirel DB, Posthuma D, Sabatti C, Eskin E, Conti DV, Knowles JA, Ruiz-Linares A, Rouleau GA, Purcell S, Heutink P, Oostra BA, McMahon WM, Freimer NB, Cox NJ, Pauls DL. Genome-wide association study of Tourette’s syndrome. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18(6):721–728. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SE, Illmann C, Geller DA, Leckman JF, King R, Pauls DL. A controlled family study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and Tourette’s disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1354–1362. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000251211.36868.fe. S0890-8567(09)61918-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Bagner D, Merlo LJ, Shapira NA, Geffken GR, Murphy TK, Goodman WK. Florida obsessive-compulsive inventory: Development, reliability, and validity. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(9):851–859. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20382. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson J, Nolan W, Pelham W. [14.11.2009];The SNAP-IV rating scale. 1992 http://www.adhd.net.

- Tamara P. Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders of childhood. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;112:853–856. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52910-7.00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourette Syndrome Association International Consortium for Genetics. Genome scan for Tourette disorder in affected-sibling-pair and multigenerational families. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;80(2):265–272. doi: 10.1086/511052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu D, Mathews CA, Scharf JM, Neale BM, Davis LK, Gamazon ER, Derks EM, Evans P, Edlund CK, Crane J, Fagerness JA, Osiecki L, Gallagher P, Gerber G, Haddad S, Illmann C, McGrath LM, Mayerfeld C, Arepalli S, Barlassina C, Barr CL, Bellodi L, Benarroch F, Berrio GB, Bienvenu OJ, Black DW, Bloch MH, Brentani H, Bruun RD, Budman CL, Camarena B, Campbell DD, Cappi C, Silgado JC, Cavallini MC, Chavira DA, Chouinard S, Cook EH, Cookson MR, Coric V, Cullen B, Cusi D, Delorme R, Denys D, Dion Y, Eapen V, Egberts K, Falkai P, Fernandez T, Fournier E, Garrido H, Geller D, Gilbert DL, Girard SL, Grabe HJ, Grados MA, Greenberg BD, Gross-Tsur V, Grunblatt E, Hardy J, Heiman GA, Hemmings SM, Herrera LD, Hezel DM, Hoekstra PJ, Jankovic J, Kennedy JL, King RA, Konkashbaev AI, Kremeyer B, Kurlan R, Lanzagorta N, Leboyer M, Leckman JF, Lennertz L, Liu C, Lochner C, Lowe TL, Lupoli S, Macciardi F, Maier W, Manunta P, Marconi M, McCracken JT, Mesa Restrepo SC, Moessner R, Moorjani P, Morgan J, Muller H, Murphy DL, Naarden AL, Nurmi E, Ochoa WC, Ophoff RA, Pakstis AJ, Pato MT, Pato CN, Piacentini J, Pittenger C, Pollak Y, Rauch SL, Renner T, Reus VI, Richter MA, Riddle MA, Robertson MM, Romero R, Rosario MC, Rosenberg D, Ruhrmann S, Sabatti C, Salvi E, Sampaio AS, Samuels J, Sandor P, Service SK, Sheppard B, Singer HS, Smit JH, Stein DJ, Strengman E, Tischfield JA, Turiel M, Valencia Duarte AV, Vallada H, Veenstra-VanderWeele J, Walitza S, Wang Y, Weale M, Weiss R, Wendland JR, Westenberg HG, Shugart YY, Hounie AG, Miguel EC, Nicolini H, Wagner M, Ruiz-Linares A, Cath DC, McMahon W, Posthuma D, Oostra BA, Nestadt G, Rouleau GA, Purcell S, Jenike MA, Heutink P, Hanna GL, Conti DV, Arnold PD, Freimer NB, Stewart SE, Knowles JA, Cox NJ, Pauls DL. Cross-Disorder Genome-Wide Analyses Suggest a Complex Genetic Relationship Between Tourette’s Syndrome and OCD. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(1):82–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101306. 1900626 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]