Abstract

MDMA is a widely abused psychostimulant which causes a rapid and robust release of the monoaminergic neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin. Recently, it was shown that MDMA increases extracellular glutamate concentrations in the dorsal hippocampus, which is dependent on serotonin release and 5HT2A/2C receptor activation. The increased extracellular glutamate concentration coincides with a loss of parvalbumin-immunoreactive (PV-IR) interneurons of the dentate gyrus region. Given the known susceptibility of PV interneurons to excitotoxicity, we examined whether MDMA-induced increases in extracellular glutamate in the dentate gyrus are necessary for the loss of PV cells in rats. Extracellular glutamate concentrations increased in the dentate gyrus during systemic and local administration of MDMA. Administration of the NMDA receptor antagonist, MK-801, during systemic injections of MDMA, prevented the loss of PV-IR interneurons seen 10 days after MDMA exposure. Local administration of MDL100907, a selective 5HT2A receptor antagonist, prevented the increases in glutamate caused by reverse dialysis of MDMA directly into the dentate gyrus and prevented the reduction of PV-IR. These findings provide evidence that MDMA causes decreases in PV within the dentate gyrus through a 5HT2A receptor-mediated increase in glutamate and subsequent NMDA receptor activation.

Keywords: MDMA, glutamate, parvalbumin, GABA, hippocampus, serotonin

1. Introduction

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, ecstasy) is a psychostimulant popular amongst both teenagers and younger adults. MDMA targets primarily the serotonin (5HT) neurotransmitter system to produce a rapid acute release of 5HT and a long-term depletion of 5HT resulting from what can be best described as a distal axotomy (Nichols et al., 1982, Johnson et al., 1986). This persistent decrease in 5HT is observed within the striatum, cortex and hippocampus and may underlie the cognitive deficits evident in human abusers of MDMA (Battaglia et al., 1987, O'Hearn et al., 1988, Parrott et al., 1998).

Several studies support the notion that MDMA-induced neurotoxicity may extend beyond serotonin terminals to include apoptosis within the hippocampus (Tamburini et al., 2006, Wang et al., 2009, Kermanian et al., 2012, Soleimani Asl et al., 2012). Further evidence for neuronal cell loss caused by MDMA originates from recent reports of a loss of parvalbumin (PV) interneurons in the dentate gyrus of MDMA-exposed rodents (Anneken et al., 2013, Abad et al., 2014). These studies concluded that the loss of PV interneurons is associated with MDMA-induced increases in hippocampal glutamate; however, a direct causal role for glutamate receptor activation in mediating this effect remains to be established. Along these lines, PV neurons express mGluR1/5 receptors, GluR2 lacking AMPA receptors as well as NMDA receptors within the hippocampus such that their coordinate or convergent activation may convey susceptibility to excitotoxicity (Kerner et al., 1997, Catania et al., 1998, Le Roux et al., 2013). In fact, decreases in PV immunoreactivity (PV-IR) are evident after neurotoxic insults in which glutamate neurotransmission is a presumed mechanism (Kwon et al., 1999, Gorter et al., 2001, Sanon et al., 2005).

The increases in extracellular glutamate concentrations caused by systemic injections of MDMA appear to be mediated by 5HT efflux and prevented by the systemic injections of the non-specific 5HT2 receptor antagonist ketanserin (Anneken and Gudelsky, 2012, Anneken et al., 2013). It remains to be determined which 5HT2 receptor subtype within the hippocampus mediates the increases in extracellular glutamate concentrations. Therefore, the current study determined if 5HT2A and/or NMDA receptor activation within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus during MDMA exposure is responsible for the increases in extracellular glutamate and decreases in PV-IR.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–275 g. Harlan Sprague Dawley, In, USA) were used in all experiments. Upon arrival, rats were grouped two rats per cage and allowed one week to acclimate. The rats were kept on a 12/12-hr light dark cycle in a temperature and humidity controlled room with food and water available ad libitum. All procedures were performed in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and in approval with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Toledo.

2.2 Drug Treatments

MDMA was obtained from the National Institutes of Drug Abuse (NIDA, Research Triangle). For PV cell count experiments, rats were injected with 0.9% (1 ml/kg) saline or MDMA (7.5 mg/kg, once every 2 hours X 4 injections). MDL100907 (generous gift from Wyeth) and MK801 (Tocris) were dissolved in saline with a pH 3 (adjusted with HCl) and were given via IP injections (0.1mg/kg), 30 minutes before each administration of MDMA. These doses were based on previous studies where this dose was used (Schreiber et al., 1998, Tutka et al., 2002). Core body temperatures were recorded 1 hour after each injection of saline or MDMA using a rectal probe digital thermometer (Thermalert TH-8, Physitemp Instruments). To control for decreases in MDMA-induced hyperthermia caused by MK801 or MDL100907, treatments of these groups were performed in an elevated ambient temperature (28.7°C).

2.3 Microdialysis

Rats were anesthetized with a xylazine/ketamine hydrochloride mixture (6/70 mg/kg i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). The active membrane (~1mm, 13KDa cutoff) of a microdialysis probe was placed in the dentate gyrus of the dorsal hippocampus (coordinates: 3.9 mm rostral from bregma, 2.2 mm lateral from the midline and 4.2 mm ventral). Three additional holes, with stainless steel screws were placed in the skull to act as anchors for the dental cement.

The morning after surgeries, Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (138 mM NaCl, 2.1 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 8.1 mm NaHPO4, 1.2 mm CaCl2, and 0.5 mM D-glucose, pH 7.4) (Sigma-Aldrich) was perfused at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min using a model 22 syringe perfusion pump (Harvard Apparatus). After a 1 hour equilibration period, four 30 minute baseline samples were collected. MDMA exposure began immediately following baseline collections and dialysate samples were collected every hour. MDMA exposure consisted of either 4 i.p. injections of 7.5 mg/kg, each injection given every other hour or reverse dialysis of 100 μM MDMA directly into the dentate gyrus. Reverse dialysis of the antagonists (100 nM) MDL100907 was started 30 minutes prior to reverse dialysis of MDMA. This dose was used based on previous findings highlighting selectivity of MDL100907 for 5HT2A receptors as compared to 5HT2C receptors (Kehne et al., 1996). Brains from rats used for microdialysis were sectioned and probe placement was verified.

2.4 High-performance Liquid Chromatography Analysis of Extracellular Glutamate

Dialysate samples (20μl) were injected onto a C18 column (150 x 2mm, 3μm particle filter, Phenomenex) and were eluted using a mobile phase which consisted of 0.1 M Na2HPO4, 0.1mM EDTA and 10% methanol (pH 6.4). As previous described, o-pthaldialdehyde was used to derivatize glutamate for electrochemical detection a using a LC-4C amperometric detector (BAS Inc.) (Donzanti and Yamamoto, 1988).

2.5 Immunohistochemistry

Fixation of the brain was performed by transcardially perfusing 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde on the 10th day after drug or saline exposure. Brains were cryoprotected, flash frozen and hippocampi sectioned into 50 μm thick slices. Sections were treated with 1% H2O2 for 30 min at room temperature (RT). The sections were blocked for 2 hr at RT with 10% normal goat serum (Life Technologies) in 0.1M PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X 100 and Avidin block (4 drops/mL; Vector Laboratories). For PV immunostaining, 50μm thick sections were incubated for 36 hr at 4°C with a mouse monoclonal PV antibody (1:2000; Swant, cat# PV235) in 0.1 M PBS containing 0.5% Triton-X 100, 1% NGS and Biotin block (4 drops/ml; Vector Laboratories). Sections were then incubated in goat anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibodies (Millipore, cat# AP124b) for 2hr at RT followed by incubation in avidin-biotin- horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit; Vector Laboratories) for 2hr at RT. Sections were then developed in diaminobenzidine (DAB/Metal Concentrate; Pierce) and mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Eukitt mounting medium (Sigma- Aldrich). All slides were coded and the code was not broken until the end of quantitative analysis.

2.6 Stereology

To assess PV-IR GABA interneurons in the dorsal hippocampus, a modified optical fractionator counting technique was used (West et al., 1991, Gundersen et al., 1999). Neuronal counts were made using a BX51 Olympus microscope equipped with a DVC camera interfaced with StereoInvestigator 8.21 software (MBF Bioscience). During quantification, every fourth section for a total of six sections through the dorsal hippocampus was systematically sampled. A border which contained the granule cell layer and hilus region was drawn with a 10x objective and counts were performed using a 20x objective. Tissue shrinkage due to processing prevented the use of guard zones above and below the dissector. PV counts were performed using 100μm X 100μm grid dimensions. Parameters for stereology experiments were determined in order to obtain a Gunderson coefficient of around 0.1 or below, which allows for an accurate estimate of total PV interneurons within the region.

2.7 Statistical Analyses

Stereological neuronal counts were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA to compare the effects of saline or MDMA and an interaction between these effects and that of the antagonists (MK801 or MDL100907). Extracellular glutamate concentrations were compared between groups using a two-way ANOVA with repeated measures. Post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s test. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05

3. Results

3.1 Effects of systemic injections of MDMA on extracellular glutamate concentrations in the dentate gyrus

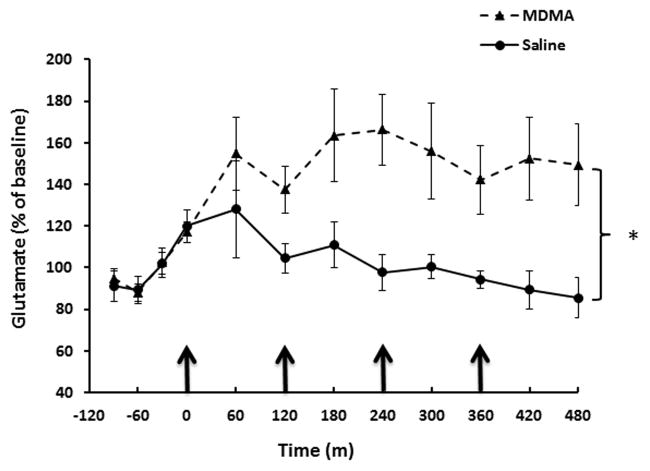

The effects of systemic injections of MDMA (7.5 mg/kg x 4 injections, each injection every 2 hrs) on extracellular glutamate concentrations within the dentate gyrus were determined via microdialysis. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant effect of MDMA treatment on extracellular glutamate concentrations (F(1,110)=9.635; P<0.01). Extracellular glutamate concentrations were significantly increased 1 hour after the second injection of MDMA (P<0.05) and at subsequent sample collection times (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of systemic MDMA injections on extracellular glutamate levels within the dentate gyrus. Rats received MDMA (7.5mg/kg every 2h X 4 i.p. injections) or saline (1mL/kg, every 2h). n=8–12 per group. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of MDMA treatment (P<0.005) *=statistically significant from saline treated controls (P<0.05).

3.2 NMDA receptor inhibition prevents MDMA-induced PV cell losses

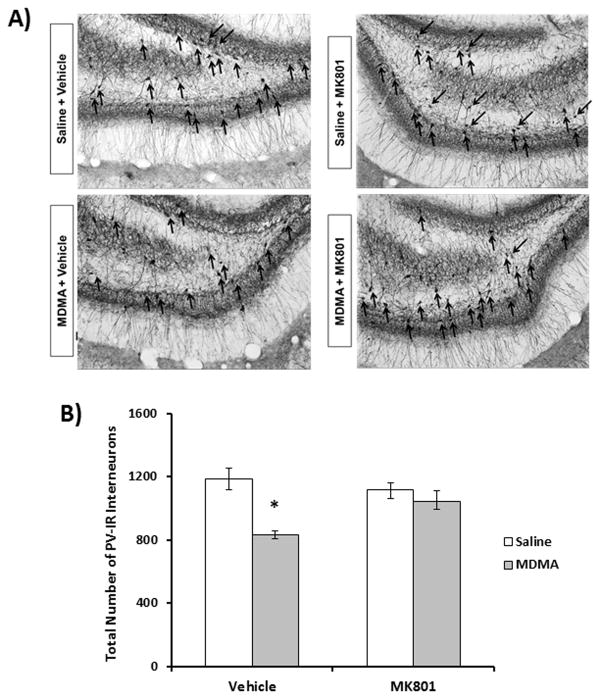

The role of NMDA receptor activation in mediating MDMA-induced PV deficits within the dentate gyrus was examined. Representative images (10x magnification) of the dentate gyrus from treatment groups, 10 days following drug exposure are shown in Fig. 2A. PV cells within the dentate gyrus were localized to the granule cell layer and hilus region. MDMA+vehicle treated rats had significantly fewer (30%, P<0.001) PV interneurons in the dentate gyrus than saline vehicle treated control animals. MDMA+vehicle treated animals had significantly increased core body temperatures (P<0.05) compared to saline+vehicle controls, but were not significantly different than MDMA+MK801 treated animals (mean temperatures were 39.1 °C and 39.2 °C for MDMA+vehicle and MDMA+MK801 respectively (data not shown). As shown in fig. 2B, two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of MDMA on PV cells (F(1,27)=22.7; P<0.001) as well as an interaction between MDMA and MK801 treatment on PV cell counts (F(1,27)=9.283; P<0.01). PV cell counts in the dentate gyrus of rats treated with MK801 prior to and during MDMA exposure were not significantly different from saline vehicle controls.

Fig. 2.

Effect of MK801 on MDMA-induced PV-ir interneuron decreases in the dentate gyrus. Rats were treated with MK801 (0.1mg/kg, i.p.) 30 minutes prior to each MDMA (7.5mg/kg every 2h X 4 i.p injections) or saline injection. Ten days after exposure, stereologic assessment of dentate PV-IR interneurons was performed. A) Representative photomicrographs of PV-IR for treatment groups with PV positive cells labeled with black arrows. B) Quatitative assessment of PV-IR (n=5–8 per group). MDMA+vehicle significantly decreased PV-IR neurons in the dentate gyrus compared to saline+vehicle treatments (P<0.001). MK801 pretreatment prevented decreases in PV cell counts caused by MDMA (P<0.005). *=statistically significant from saline+vehicle controls (P<0.05).

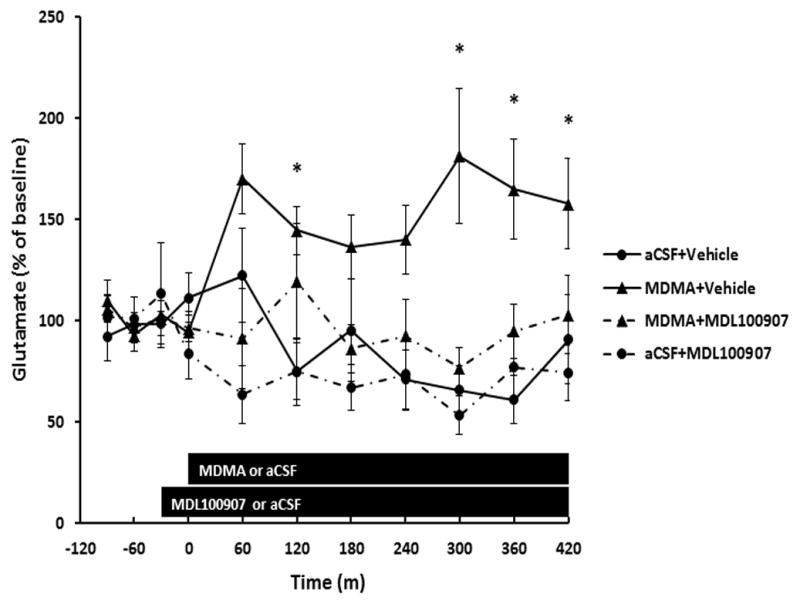

3.3 MDL100907 prevents increased glutamate concentrations caused by local perfusion of MDMA

The effects of local administration of the 5HT2A receptor antagonist MDL100907 on extracellular glutamate increases caused by reverse dialysis of 100 μM MDMA into the dentate gyrus was determined. As shown in Fig. 3, reverse dialysis of 100 μM MDMA+vehicle resulted in a significant increase in extracellular glutamate concentrations compared to aCSF+vehicle (P<0.01). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA on MDMA+vehicle and aCSF+vehicle groups revealed a significant effect of MDMA treatment (F(1,100)=6.68; P<0.05) and time(F(6,100)=2.27; P<0.05). A significant effect of MDL100907 treatment (F(1,107)=4.95; P<0.05) was revealed when two-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed on MDMA+vehicle and MDMA+MDL10097 groups. Additionally, extracellular glutamate concentrations were not significantly different between MDMA+MDL100907 and aCSF+vehicle groups.

Fig. 3.

MDL100907 prevents increases in extracellular glutamate within the dentate gyrus caused by reverse dialysis 100μM MDMA. Microdialysis measurements of extracellular glutamate concentrations were performed in the dentate gyrus in which 100μM of MDMA was perfused for 7 hours (noted by bar). MDL100907 (100nM) or vehicle was reverse dialysed 30 minutes prior and during MDMA. n=6–11 per group. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of MDMA (P<0.05). MDL100907 prevented MDMA-induced increases in glutamate (P<0.05). * denotes values statistically significant from aCSF+vehicle controls (P<0.05).

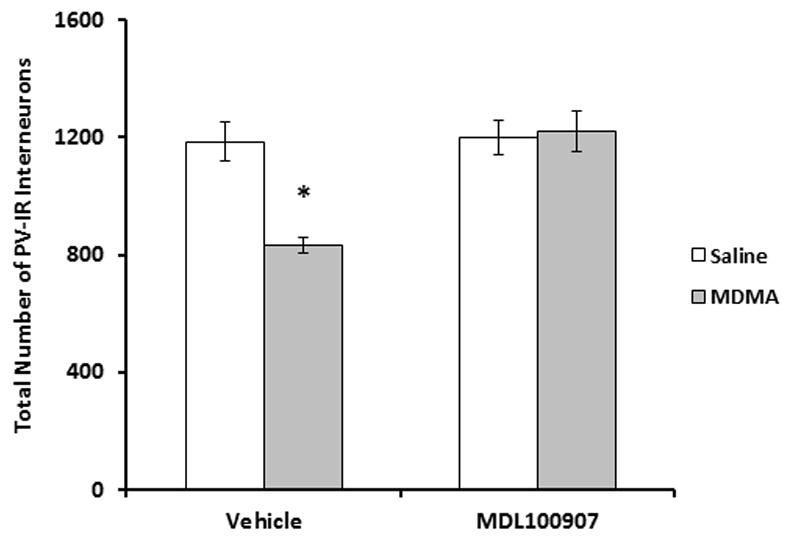

3.4 Effect of MDL100907 on MDMA-induced PV cell losses

The ability of MDL100907 to prevent MDMA-induced decreases in PV cell counts was determined. As shown in Fig. 4, MDMA+vehicle treated animals had significantly fewer PV interneurons in the dentate gyrus compared with saline+vehicle treated rats (P<0.05). A two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a main effect of MDMA (F(1,21)=9.26; P<0.01) as well as an interaction between MDMA and MDL100907 (F(1,21)=11.5; P<0.01) on the decreases in the number of PV-positive cells. MDL100907 prior to and during MDMA exposure blocked the decrease in PV cell counts and were not significantly different from saline vehicle controls. Core body temperatures of MDMA+MDL100907 treated rats did not differ significantly from those of MDMA+vehicle treated rats (mean temperatures were 39.1 °C and 39 °C. for MDMA+vehicle and MDMA+MDL100907, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Effect of MDL100907 on MDMA-induced PV-ir interneuron decreases in the dentate gyrus. Rats were treated with MDL100907 (0.1mg/kg) 30 minutes prior to each MDMA (7.5mg/kg every 2h X 4 injections) or saline injection. Ten days following exposure, stereologic assessment of dentate PV-ir interneurons was performed. PV counts for saline+vehicle and MDMA+vehicle groups are repeated from Fig. 2. n=6–8 per group. MDMA+vehicle significantly reduced PV-IR neurons in the dentate gyrus compared to saline+vehicle treatments (P<0.001). MDL100907 pretreatment prevented MDMA-induced decreases in PV neurons (P<0.001). *=statistically significant from saline+vehicle controls (P<0.05).

4. Discussion

Our findings support a role for glutamate within the dentate gyrus in mediating the long-term loss of PV interneurons caused by MDMA. It has been reported that systemic injections of MDMA as well as reverse dialysis of 100 μM MDMA increased glutamate concentrations within the hippocampus; however these experiments did not localize this effect to the dentate gyrus where PV cell losses occur (Anneken and Gudelsky, 2012, Anneken et al., 2013). We found that both the systemic injections of 7.5mg/kg MDMA (1 injection given every 2 hr for a total of 4 injections) as well as the direct administration of 100 μM MDMA into the dentate gyrus produced an increase in extracellular glutamate concentrations within the dentate gyrus. Therefore, these findings support the idea that the loss of PV interneurons in the dentate gyrus is a result of local increases in glutamate during MDMA exposure.

PV interneurons within the hippocampus are known to express NMDA receptors (Le Roux et al., 2013). Antagonism of NMDA receptors during MDMA exposure prevented the deficits in PV interneurons observed 10 days following MDMA exposure (Fig. 2). This effect was not dependent on the ability of MK801 to reduce MDMA-induced hyperthermia (Colado et al., 1998) since the increases in body temperatures between MDMA and MDMA+MK801 groups were similar. Our findings that MK801 pretreatment is able to prevent MDMA-induced decreases in PV cell numbers support the conclusion that increases in glutamate during MDMA exposure play a role in the PV cell losses through increased activation of NMDA receptors. Other studies have reported deficits in PV interneurons within the hippocampus resulting from neurotoxic insults where excitotoxicity is a presumed mechanism (Phillips et al., 1998, Kwon et al., 2000). These studies showed that these PV deficits could be prevented through inactivation of NMDA receptors. Because NMDA receptor activation plays a role in mediating excitotoxicity, it is possible that MDMA-induced glutamate increases are excitotoxic through activation of NMDA receptors on PV interneurons.

Anneken and Gudelsky (2012) concluded that the increases in hippocampal glutamate concentrations were the result of MDMA-induced increases in serotonin and subsequent 5HT2 receptor activation. In support of this conclusion, we found that MDL100907, an antagonist with high selectivity for 5HT2A receptors, prevented MDMA-induced glutamate increases in the dentate gyrus. Immunoreactivity of 5HT2A receptors is known to be relatively dense in the dentate gyrus, in particular the hilus region bordering the granule cell layer, and is similar to the densities of PV expressing interneurons in the region (Fig. 2A) (Luttgen et al., 2004). The relative density of serotonin innervation follows a similar pattern to that of 5HT2A receptor expression (Moore and Halaris, 1975). Thus, MDMA causes the release of 5HT to presumably increase 5HT2A receptor activation within the dentate gyrus.

5HT2A receptors within the dentate gyrus are known to be expressed by astrocytes and granule cells within the dentate gyrus (Xu and Pandey, 2000). MDMA-induced 5HT and activation of 5HT2A receptors would increase downstream signaling cascades including the activation of phospholipases. 5HT2A receptors in comparison to 5HT2C receptors are known to preferentially activate phospholipase A2 and subsequent arachidonate production (Felder et al., 1990, Berg et al., 1998). Arachidonate production could thus contribute to cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) mediated synthesis of prostaglandins such as PGE2, to increase glutamate release from astrocytes and neurons and cause excitotoxicity (Bezzi et al., 1998, Lin et al., 2014). It was previously reported that MDMA-induced increases in glutamate within the hippocampus could be prevented via inhibition of COX2 (Anneken et al., 2013) and supports the interpretation that MDMA-induced increases in glutamate (Figs. 1 and 3) are mediated via activation of 5HT2A receptors (see Fig. 3) with subsequent production of prostaglandins.

As mentioned, the localization of 5HT innervations and 5HT2A receptors is particularly dense within the inner portions of the granule cell layer and hilus region (Luttgen et al., 2004). This corresponds with the pattern of PV interneuron localization within the dentate gyrus and suggests that PV cells in this region have an increased likelihood of being impacted by increased 5HT2A receptor activation and subsequent increases in glutamate caused by MDMA. In support of this idea, we found that the 5HT2A receptor antagonist MDL100907 prevents MDMA-induced decreases in PV cells observed 10 days later (Fig. 4). The PV decreases are not mediated by the reduction in MDMA-induced hyperthermia since the average core body temperatures were similar between MDMA+vehicle and MDMA+MDL100907 treated rats.

The loss of PV interneurons following MDMA exposure may help explain a number of findings that suggest MDMA exposure may impair inhibition within the hippocampus and promote a loss of hippocampal function. PV interneurons within the dentate gyrus are known to synapse directly onto the somatic region of granule cells, which allows them to exert strong inhibitory control of action potential firing (Freund and Buzsaki, 1996, Miles et al., 1996). For this reason, a dysfunction in PV interneuron activity has been implicated in epileptogenesis. Along these lines, MDMA exposure in rodents has been shown to increase susceptibility to kainate induced seizures which correlates with a loss of PV interneurons within the dentate gyrus (Giorgi et al., 2005, Abad et al., 2014). In addition, PV interneurons play a role in feed-forward and feed-back inhibition within the dentate gyrus and thereby are integral components of information processing within the hippocampus (Kneisler and Dingledine, 1995a,b). Thus, a loss of PV interneurons could potentially impair hippocampus-mediated information processing. In fact, several studies have reported spatial memory impairments typically associated with dysfunction of hippocampal based cognitive processes in both adolescent and adult rats treated with MDMA (Robinson et al., 1993, Sprague et al., 2003, Williams et al., 2003, Vorhees et al., 2004, Skelton et al., 2006, Arias-Cavieres et al., 2010). Further studies are needed to determine the extent to which GABAergic function is impaired in the hippocampus after MDMA and whether these impairments underlie changes in hippocampus-mediated cognitive function caused by exposure to the drug.

In conclusion, MDMA-induced decreases in PV interneurons are mediated by the 5HT2A receptor, increases in glutamate neurotransmission and subsequent activation of NMDA receptors within the dentate gyrus during MDMA exposure. These effects of MDMA on PV interneurons within the hippocampus may have a significant impact on hippocampal physiology and explain spatial memory deficits as well as seizure susceptibility in animals treated with MDMA or human MDMA abusers.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health USA grant R01 DA07606 and DA07427.

Abbreviations

- MDMA

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

- PV

parvalbumin

- PV-IR

parvalbumin immunoreactive

- 5HT

serotonin

- GABA

gamma-Aminobutyric acid

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-aspartate

- AMPA

α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- RT

room temperature

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase 2

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abad S, Junyent F, Auladell C, Pubill D, Pallas M, Camarasa J, Escubedo E, Camins A. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine enhances kainic acid convulsive susceptibility. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2014;54:231–242. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anneken JH, Cunningham JI, Collins SA, Yamamoto BK, Gudelsky GA. MDMA increases glutamate release and reduces parvalbumin-positive GABAergic cells in the dorsal hippocampus of the rat: role of cyclooxygenase. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology. 2013;8:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9420-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anneken JH, Gudelsky GA. MDMA produces a delayed and sustained increase in the extracellular concentration of glutamate in the rat hippocampus. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63:1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Cavieres A, Rozas C, Reyes-Parada M, Barrera N, Pancetti F, Loyola S, Lorca RA, Zeise ML, Morales B. MDMA ("ecstasy") impairs learning in the Morris Water Maze and reduces hippocampal LTP in young rats. Neuroscience letters. 2010;469:375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia G, Yeh SY, O'Hearn E, Molliver ME, Kuhar MJ, De Souza EB. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine and 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine destroy serotonin terminals in rat brain: quantification of neurodegeneration by measurement of [3H]paroxetine-labeled serotonin uptake sites. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1987;242:911–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Maayani S, Goldfarb J, Clarke WP. Pleiotropic behavior of 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptor agonists. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;861:104–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzi P, Carmignoto G, Pasti L, Vesce S, Rossi D, Rizzini BL, Pozzan T, Volterra A. Prostaglandins stimulate calcium-dependent glutamate release in astrocytes. Nature. 1998;391:281–285. doi: 10.1038/34651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania MV, Bellomo M, Giuffrida R, Giuffrida R, Stella AM, Albanese V. AMPA receptor subunits are differentially expressed in parvalbumin- and calretinin-positive neurons of the rat hippocampus. The European journal of neuroscience. 1998;10:3479–3490. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colado MI, Granados R, O'Shea E, Esteban B, Green AR. Role of hyperthermia in the protective action of clomethiazole against MDMA ('ecstasy')-induced neurodegeneration, comparison with the novel NMDA channel blocker AR-R15896AR. British journal of pharmacology. 1998;124:479–484. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzanti BA, Yamamoto BK. An improved and rapid HPLC-EC method for the isocratic separation of amino acid neurotransmitters from brain tissue and microdialysis perfusates. Life sciences. 1988;43:913–922. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(88)90267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felder CC, Kanterman RY, Ma AL, Axelrod J. Serotonin stimulates phospholipase A2 and the release of arachidonic acid in hippocampal neurons by a type 2 serotonin receptor that is independent of inositolphospholipid hydrolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1990;87:2187–2191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF, Buzsaki G. Interneurons of the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1996;6:347–470. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:4<347::AID-HIPO1>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi FS, Pizzanelli C, Ferrucci M, Lazzeri G, Faetti M, Giusiani M, Pontarelli F, Busceti CL, Murri L, Fornai F. Previous exposure to (+/−) 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine produces long-lasting alteration in limbic brain excitability measured by electroencephalogram spectrum analysis, brain metabolism and seizure susceptibility. Neuroscience. 2005;136:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Lopes da Silva FH. Progression of spontaneous seizures after status epilepticus is associated with mossy fibre sprouting and extensive bilateral loss of hilar parvalbumin and somatostatin-immunoreactive neurons. The European journal of neuroscience. 2001;13:657–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB, Kieu K, Nielsen J. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology--reconsidered. Journal of microscopy. 1999;193:199–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Hoffman AJ, Nichols DE. Effects of the enantiomers of MDA, MDMA and related analogues on [3H]serotonin and [3H]dopamine release from superfused rat brain slices. European journal of pharmacology. 1986;132:269–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90615-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehne JH, Baron BM, Carr AA, Chaney SF, Elands J, Feldman DJ, Frank RA, van Giersbergen PL, McCloskey TC, Johnson MP, McCarty DR, Poirot M, Senyah Y, Siegel BW, Widmaier C. Preclinical characterization of the potential of the putative atypical antipsychotic MDL 100,907 as a potent 5-HT2A antagonist with a favorable CNS safety profile. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1996;277:968–981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermanian F, Mehdizadeh M, Soleimani M, Ebrahimzadeh Bideskan AR, Asadi-Shekaari M, Kheradmand H, Haghir H. The role of adenosine receptor agonist and antagonist on Hippocampal MDMA detrimental effects; a structural and behavioral study. Metabolic brain disease. 2012;27:459–469. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner JA, Standaert DG, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB, Landwehrmeyer GB. Expression of group one metabotropic glutamate receptor subunit mRNAs in neurochemically identified neurons in the rat neostriatum, neocortex, and hippocampus. Brain research Molecular brain research. 1997;48:259–269. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneisler TB, Dingledine R. Spontaneous and synaptic input from granule cells and the perforant path to dentate basket cells in the rat hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1995a;5:151–164. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kneisler TB, Dingledine R. Synaptic input from CA3 pyramidal cells to dentate basket cells in rat hippocampus. The Journal of physiology. 1995b;487 ( Pt 1):125–146. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YB, Yang IS, Kang KS, Han HJ, Lee YS, Lee JH. Effects of dizocilpine pretreatment on parvalbumin immunoreactivity and Fos expression after cerebral ischemia in the hippocampus of the Mongolian gerbil. The Journal of veterinary medical science / the Japanese Society of Veterinary Science. 2000;62:141–146. doi: 10.1292/jvms.62.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YB, Yoon YS, Han HJ, Lee JH. Effect of 7-nitroindazole, a selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, on parvalbumin immunoreactivity after cerebral ischaemia in the hippocampus of the Mongolian gerbil. Anatomia, histologia, embryologia. 1999;28:325–329. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0264.1999.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux N, Cabezas C, Bohm UL, Poncer JC. Input-specific learning rules at excitatory synapses onto hippocampal parvalbumin-expressing interneurons. The Journal of physiology. 2013;591:1809–1822. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.245852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY, Lu CW, Wang CC, Huang SK, Wang SJ. Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor celecoxib inhibits glutamate release by attenuating the PGE2/EP2 pathway in rat cerebral cortex endings. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2014;351:134–145. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.217372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttgen M, Ove Ogren S, Meister B. Chemical identity of 5-HT2A receptor immunoreactive neurons of the rat septal complex and dorsal hippocampus. Brain research. 2004;1010:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Toth K, Gulyas AI, Hajos N, Freund TF. Differences between somatic and dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:815–823. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Halaris AE. Hippocampal innervation by serotonin neurons of the midbrain raphe in the rat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1975;164:171–183. doi: 10.1002/cne.901640203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols DE, Lloyd DH, Hoffman AJ, Nichols MB, Yim GK. Effects of certain hallucinogenic amphetamine analogues on the release of [3H]serotonin from rat brain synaptosomes. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 1982;25:530–535. doi: 10.1021/jm00347a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hearn E, Battaglia G, De Souza EB, Kuhar MJ, Molliver ME. Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) cause selective ablation of serotonergic axon terminals in forebrain: immunocytochemical evidence for neurotoxicity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1988;8:2788–2803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-08-02788.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott AC, Lees A, Garnham NJ, Jones M, Wesnes K. Cognitive performance in recreational users of MDMA of 'ecstasy': evidence for memory deficits. Journal of psychopharmacology. 1998;12:79–83. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips LL, Lyeth BG, Hamm RJ, Reeves TM, Povlishock JT. Glutamate antagonism during secondary deafferentation enhances cognition and axo-dendritic integrity after traumatic brain injury. Hippocampus. 1998;8:390–401. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:4<390::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Castaneda E, Whishaw IQ. Effects of cortical serotonin depletion induced by 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) on behavior, before and after additional cholinergic blockade. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 1993;8:77–85. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanon N, Carmant L, Emond M, Congar P, Lacaille JC. Short-term effects of kainic acid on CA1 hippocampal interneurons differentially vulnerable to excitotoxicity. Epilepsia. 2005;46:837–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.21404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R, Melon C, De Vry J. The role of 5-HT receptor subtypes in the anxiolytic effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the rat ultrasonic vocalization test. Psychopharmacology. 1998;135:383–391. doi: 10.1007/s002130050526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelton MR, Williams MT, Vorhees CV. Treatment with MDMA from P11-20 disrupts spatial learning and path integration learning in adolescent rats but only spatial learning in older rats. Psychopharmacology. 2006;189:307–318. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0563-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani Asl S, Farhadi MH, Moosavizadeh K, Samadi Kuchak Saraei A, Soleimani M, Jamei SB, Joghataei MT, Samzadeh-Kermani A, Hashemi-Nasl H, Mehdizadeh M. Evaluation of Bcl-2 Family Gene Expression in Hippocampus of 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine Treated Rats. Cell journal. 2012;13:275–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague JE, Preston AS, Leifheit M, Woodside B. Hippocampal serotonergic damage induced by MDMA (ecstasy): effects on spatial learning. Physiology & behavior. 2003;79:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburini I, Blandini F, Gesi M, Frenzilli G, Nigro M, Giusiani M, Paparelli A, Fornai F. MDMA induces caspase-3 activation in the limbic system but not in striatum. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1074:377–381. doi: 10.1196/annals.1369.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tutka P, Olszewski K, Wozniak M, Kleinrok Z, Czuczwar SJ, Wielosz M. Molsidomine potentiates the protective activity of GYKI 52466, a non-NMDA antagonist, MK-801, a non-competitive NMDA antagonist, and riluzole against electroconvulsions in mice. European neuropsychopharmacology : the journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;12:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhees CV, Reed TM, Skelton MR, Williams MT. Exposure to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) on postnatal days 11–20 induces reference but not working memory deficits in the Morris water maze in rats: implications of prior learning. International journal of developmental neuroscience : the official journal of the International Society for Developmental Neuroscience. 2004;22:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhu SP, Kuang WH, Li J, Sun X, Huang MS, Sun XL. Neuron apoptosis induced by 3,4-methylenedioxy methamphetamine and expression of apoptosis-related factors in rat brain. Sichuan da xue xue bao Yi xue ban = Journal of Sichuan University Medical science edition. 2009;40:1000–1002. 1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in thesubdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. The Anatomical record. 1991;231:482–497. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT, Morford LL, Wood SL, Rock SL, McCrea AE, Fukumura M, Wallace TL, Broening HW, Moran MS, Vorhees CV. Developmental 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) impairs sequential and spatial but not cued learning independent of growth, litter effects or injection stress. Brain research. 2003;968:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Pandey SC. Cellular localization of serotonin(2A) (5HT(2A)) receptors in the rat brain. Brain research bulletin. 2000;51:499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]