Abstract

We have recently reported that the extracellular enamel protein amelogenin has affinity to interact with phospholipids and proposed that such interactions may play key roles in enamel biomineralization as well as reported amelogenin signaling activities. Here, in order to identify the liposome-interacting domains of amelogenin we designed four different amelogenin mutants containing only a single tryptophan at positions 25, 45, 112 and 161. Circular dichroism studies of the mutants confirmed that they are structurally similar to the wild-type amelogenin. Utilizing the intrinsic fluorescence of single tryptophan residues and fluorescence resonance energy transfer FRET, we analyzed the accessibility and strength of their binding with an ameloblast cell membrane-mimicking model membrane (ACML) and a negatively charged liposome used as a membrane model. We found that amelogenin has membrane-binding ability mainly via its N-terminal, close to residues W25 and W45. Significant blue shift was also observed in the fluorescence of a N-terminal peptide following addition of liposomes. We suggest that, among other mechanisms, enamel malformation in cases of Amelogenesis Imperfecta (AI) with mutations at the N-terminal may be the result of defective amelogenin-cell interactions.

Keywords: Amelogenin, Enamel, Liposomes, Intrinsic Florescence Spectroscopy, Ameloblasts

1. Introduction

Interactions of enamel extracellular matrix components with cells are believed to be necessary for polarization, differentiation and migration of ameloblasts, the cells that assemble and build one of the most resilient mineralized tissues in mammalian body [1,2,3]. The main protein constituent of enamel extracellular matrix is amelogenin, which is critically involved in the mineralization of dental enamel [4,5]. Mutation in the amelogenin gene in humans leads to Amelogenesis Imperfecta, and complete deletion of the amelogenin gene in mice leads to thin and aprismatic enamel [5,6].

The amelogenin protein is characterized by three prominent amino acid domains: a hydrophobic 45-amino acid N-terminal domain rich in tyrosine, a large central predominantly hydrophobic proline-rich domain, and a C-terminal domain that is charged and hydrophilic [7]. The primary structures of the N- and C-terminal regions of amelogenin are almost completely conserved across mammalian species, suggesting they are critical functional domains that play important roles in amelogenesis [8]. Using bioinformatic tools as well as NMR and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy studies in solution, it has been determined that amelogenin belongs to the class of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), and is extended in its monomeric form [9].The intrinsically disordered nature provides amelogenin with conformational flexibility, contributing to its ability to recognize different targets including cell membrane. In the extracellular matrix amelogenin is likely to be in contact with charged biological surfaces such as phospholipids of the cell membrane, non-amelogenin proteins, calcium phosphate ions and apatite mineral [10,11,12,13,14].

While the function of amelogenin in controlling apatite mineralization has been extensively studied, investigations of amelogenin in matrix-cell interactions have been limited. We recently reported that interaction between amelogenin and SDS micelles led to significant changes in its secondary structure. Using CD and NMR we showed that the highly conserved N-terminal domain is prone to form a helical structure when bound to SDS micelles [15]. We further reported that amelogenin possesses liposome-binding ability with a disordered-to-ordered conformational change [16]

Four different amelogenin mutants containing only a single tryptophan (Trp161, Trp112, Trp45 or Trp25) were used for fluorescence analysis [17]. By creating these single-tryptophan amelogenins, which behaved in the same way as the wild type, we were able to identify phospholipid-interacting domains. Similar to our previous studies, we used two small unilamellar vesicles: an ameloblast cell membrane-mimicking model (ACML) and a negatively charged membrane model (POPG) [16]. The formulation of ACML, which is composed of zwitterionic phospholipids (POPC and POPE) and anionic phospholipids (POPS), was based on lipid composition information available in the literature for ameloblasts [18]. Comparison of the intrinsic fluorescence of each of the Trp mutants in the presence and absence of liposomes elucidated their binding affinity and revealed the regions with strongest binding. By analyzing the accessibility of the Trp residue in each mutant and measuring the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) from the Trp to the liposome, we determined which region of amelogenin bound most strongly to which liposome model.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein and peptide preparation

Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out on the DNA template of full-length porcine amelogenin rP172 to generate four mutant proteins, specifically rP172(W25Y,W45Y), rP172[(W25Y,W45Y,W161Y),(F112W)], rP172(W25Y,W161Y), and rP172(W45Y,W161Y), and using Quick Change mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies) as described elsewhere [15,17]. These mutants were designed such that each has only one tryptophan in its entire sequence. We refer to them here as rP172W161, rP172W112, rP172W45 and rP172W25 according to the single tryptophan remaining in the sequence. The tryptophan mutants of amelogenin (rP172) were produced using Escherichia coli BL21-codon plus ((DE3)-RP, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), expressed and purified as previously described. After selective fractionation using 20% ammonium sulfate, each mutant was dissolved in 0.1% TFA, loaded on a reverse-phase C4 column (10 × 250 mm2, 5 μm), mounted on a VarianProstar HPLC system (ProStar/Dynamics 6, version 6.41 Varian, Palo Alto, CA) and eluted with a linear gradient of 60% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. Similar to recombinant porcine amelogenin (rP172), these tryptophan mutants lack the N-terminal methionine and the phosphate in the serine at the 16th position (Figure 1A). The C-terminal (M149-D173) 25 amino acid residue peptide (25 C-term) and the TRAP polypeptide (residues M1-W45) were synthesized at the Microchemical Core Laboratory at the University of Southern California, using the Pioneer peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) following the N-Fmoc-L-aminoacid pentafluorophyenyl ester/HOBt coupling method. Peptides were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (C4–214TP54 column or C18 column; Vydac/The Separations Group, Hesperia, CA). The homogeneity was confirmed by analytical chromatography and ESI-MS measurements.

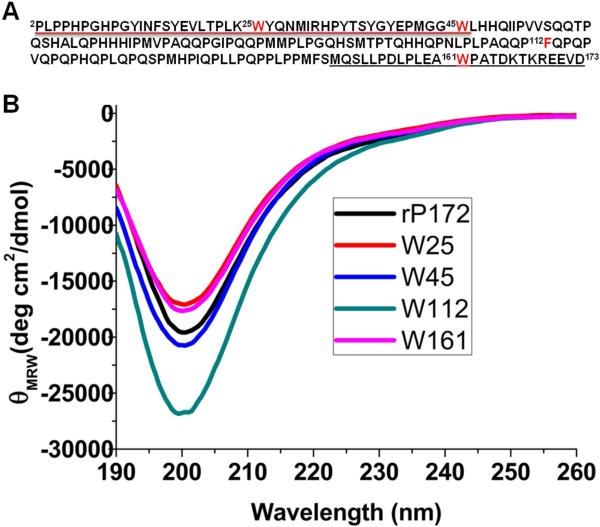

Figure 1.

(A) Amino acid sequence of porcine amelogenin (rP172). Residues denoted in red indicate the positions that were selectively mutated to generate the three double mutants and one triple mutant used in this study. The region underlined in black represents the sequence of the C-terminal 25-mer and that underlined in red represents the sequence of TRAP (note that TRAP had additional Met at the N-terminal). (B) Circular dichroism spectra show the secondary structure comparison of monomeric tryptophan mutants with the wild-type rP172 recorded at pH 3.5.

2.2. Preparation of Small Unilamellar Lipid Vesicles

POPG (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol), POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), POPA (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate), POPS (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine), POPI (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol), POPS (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine) and POPE (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine) were purchased from Avanti polar lipids, Birmingham, Al, USA. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared according to the following protocol. Ameloblast cell membrane-mimicking lipid vesicles (ACML) were prepared by mixing dry lipids POPC:POPE:POPI:POPS:POPA:Cardiolipin at a ratio of 1:2:2:2:1:2 mol/mol and dissolved in the solvent mixture (POPE was substituted with 18:1 dansyl PE for FRET experiments). Thin films of POPG and ACML were made by dissolving the appropriate amount of dry lipid powders in chloroform/methanol followed by the evaporation of the solvent mixture under a nitrogen stream. The lipid films were subjected to overnight desiccation and then hydrated in a defined volume of 25 mM Tris buffer (pH 8.0) to obtain a final concentration of 10 mM. This procedure resulted in a distinctly hazy solution characteristic of a suspension of large multilamellar vesicles. Following a standard protocol, large multilamellar vesicles were converted to SUVs by sonication in a water bath at 42 kHz in a borosilicate glass vial (12mm diameter) for 30–40 min. The size and homogeneity of the prepared SUVs were confirmed using DLS as previously reported; 300 μM of each POPG and ACML SUVs had radii of 14.3 ± 0.7 and 12.2 ± 0.2 respectively [16].

2.3. Protein Sample Preparation

The stock solutions of rP172 tryptophan mutants were prepared by dissolving 3-4 mg of pure and lyophilized protein in 1 mL of deionized water. The samples were rocked at 4 °C for 24-36 h to ensure maximum solubility. The so lution thus obtained was further centrifuged at 10,000 g for 1 h at 4 °C, in order t o avoid un-dissolved aggregates. Stock concentrations were measured through absorption at 280 nm using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Products, Wilmington, DE). An appropriate amount of buffer (25 mM Tris at pH 8.0) was added to dilute the protein stock to a final concentration of 10 μM. For titration experiments, individual samples with specific protein/lipid ratios were prepared and used. In all the experiments the final reaction volume used was 100 μL.

2.4. Tryptophan Fluorescence Spectroscopy

As all rP172 mutants had single tryptophan residue, their specific intrinsic fluorescence spectra were first obtained on a PTI QuantaMaster QM-4SE instrument (Photon Technology International, Birmingham, NJ) by exciting them at 295 nm. The extent of the lipid binding of each mutant was studied by monitoring the change in the Trp fluorescence emission (intensity and blue shift) between 310 to 400 nm upon addition of SUVs of various lipid compositions. Amelogenin-lipid binding studies were carried out by adding appropriate volumes of lipid vesicles (POPG or ACML) from a 10 mM lipid stock into a sample containing 10 μM rP172 tryptophan mutant to obtain a lipid concentration range of 10-1000 μM. For each lipid-rP172 mutant concentration, experiments were carried out separately. Corresponding solutions without rP172 tryptophan mutant were used to correct for background and SUV scattering contributions to the fluorescence signal, and spectra were also corrected for dilution effects. The data presented are maximal changes observed at a lipid/protein molar ratio of 100:1.

2.5. Acrylamide Quenching of Tryptophan Fluorescence

The extent of the burial of tryptophan residues in the lipid environment was determined by monitoring the quenching of fluorescence intensity upon addition of successive 1 μL doses of acrylamide from a stock solution of 5 M acrylamide to obtain concentrations ranging from 0.05 M to 0.25 M, in the absence and presence of lipid vesicles. Stern-Volmer plots were generated using the equation:

F0/F= 1+KSV [Q]

where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensity in the absence and presence of acrylamide quencher, respectively; [Q] is the concentration of the quencher used; and KSV is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant obtained from the slope of the curve. The net accessibility factor (NAF) was calculated from the ratio of KSV obtained from quenching of tryptophan fluorescence in the presence of lipid vesicles to its value in the absence of lipid vesicles [19].

2.6. Binding of rP172 tryptophan mutants to lipid vesicles by FRET

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) from the Trp residue of each rP172 tryptophan mutant to the dansyl (DNS) chromophore in the lipid vesicles was determined by setting the excitation monochromator at 295 nm and monitoring the fluorescence emission between 300 and 550 nm. Lipid vesicles were doped with 2 mol % of DNS-PE in buffer. The plots of FRET intensity shown are maximal changes observed at a lipid/protein ratio of 20:1.

2.7. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

Comparisons of the secondary structural properties of all the tryptophan mutants with their wild type counterpart (rP172) was done by acquiring their corresponding far-UV CD spectrum on a JASCO J-815 spectropolarimeter at pH 3.5. The concentrations of all the protein samples were maintained at 10 μM while a sample volume of 200 μL was placed in a 0.1 cm path length cuvette to record each spectrum. The temperature was maintained at 22 °C throughout. Three independent scans were recorded from 190 to 260 nm with a resolution of 0.5 nm and at a rate of 50 nm per min and averaged. The data were presented in the form of mean residue molar ellipticity.

3. Results

Amelogenin has three tryptophan residues, which reside at the 25th, 45th and 161st positions, and one phenylanaline at position 112 (Fig. 1A). The four mutant amelogenins used in our study were designed in such a way that each of the mutants has only one Trp residue in its entire sequence, and that Trp is present at one of the aforementioned positions. Through dynamic light scattering (DLS) studies we have demonstrated that these Trp mutants have similar self-assembly behavior to the wild type rP172 at both pH 5.5 (forming oligomers) and pH 8.0 (forming nanospheres) [17]. Further, circular dichroism studies of the mutants in their monomeric form confirmed that their secondary structures are highly comparable to that of their wild type counterpart (Fig.1B).Thus these mutants should be structurally and functionally similar to the wild type rP172 and they do not belong to the category of mutants that might cause Amelogenesis Imperfecta AI [6,17,20].

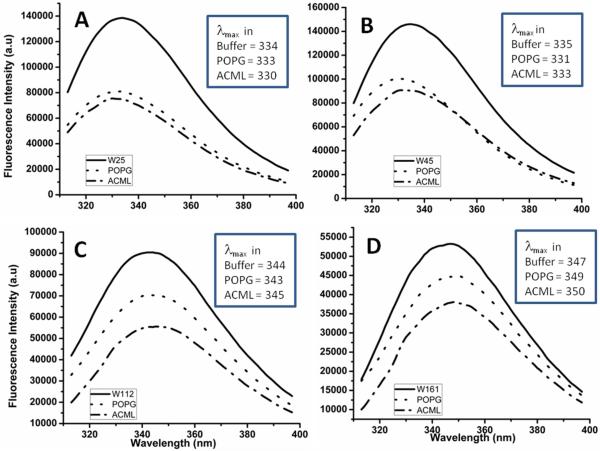

We analyzed the maximum binding ability of amelogenin mutants with the liposomes at pH 8.0, closest to physiological pH. The rP172 Trp mutants were studied as they interacted with the negatively charged liposome POPG and the ACML separately in order to identify the regions of amelogenin that interact with membranes. The presence of POPG or ACML caused a shift in the fluorescence emission maxima (λmax) of all the mutants (Fig 2). The extent to which each mutant interacted with liposomes was evident from their blue shifted maximal emission values in the presence of the liposomes. In the absence of liposomes, the Trp residues at positions 25 and 45 were buried and therefore there was a blue shift (lower λmax) in their intrinsic emission when compared to their monomers recorded at pH 3.5 (data not shown here). This is because nanosphere assembly at pH 8.0 mainly occurs via protein-protein interactions at the N-terminal region [17,21]. Following the addition of POPG and ACML liposomes, the N-terminal mutants rP172-W25 and rP172-W45 showed blue shifts (lower λmax, inset in Figs 2A and 2B). rP172-W112 and rP172-W161 exhibited λmax of 344 and 347 nm, respectively, indicating the presence of Trp residue in an aqueous environment. Addition of liposomes did not result in a significant change in their λmax values (Fig 2C and 2D). The accessibility of Trp to the aqueous quencher acrylamide was examined to shed light on the region of amelogenin responsible for liposome binding.

Figure 2.

Comparison of fluorescence emission spectra of tryptophan mutants shows the extent of their specific blue shifts in the presence of liposomes. The inset in each figure gives the λmax of each mutant in its given environment.

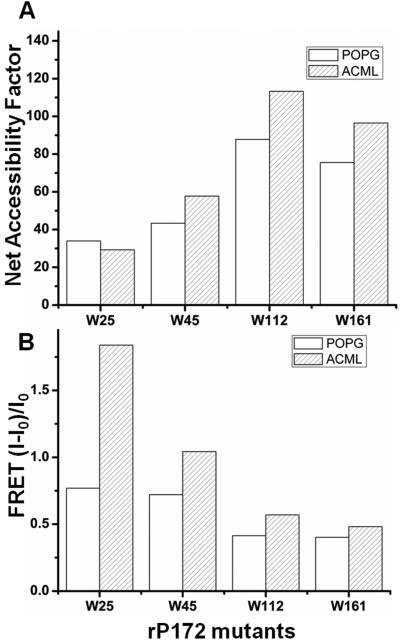

The accessibility of Trp residues in the rP172 Trp mutants to acrylamide is presented as a net accessibility factor (NAF) in Fig. 3A. As indicated in the NAF plot in Figure 3A, the Trp residues in rP172-W25 and rP172-W45 proteins are more shielded (lower NAF values 30-55) than those of Trp in rP172-W161 (higher NAF values 75-90), which suggests either self-association or association with POPG and ACML lipid vesicles. Note that the fluorescence quenching of the intrinsic tryptophan emissions of rP172-W112 and rP172-W161 were much higher in the presence of POPG and ACML lipid vesicles, as reflected by NAF values. This indicates that the C-terminal regions should be completely exposed or easily accessible for the quencher during amelogenin membrane interactions reflecting its least involvement in the binding.

Figure 3.

(A) Net accessibility factors (NAF) obtained from acrylamide quenching studies of Trp fluorescence of mutants in presence liposomes, lesser NAF value in W25, W45 and W161 signifies that Trp of these mutants are greatly buried in the hydrophobic core of lipid. (B) Comparison of FRET values of Trp mutants bound to DNS probed POPG and ACML lipid vesicles. Higher the FRET value (as noticed in ACML bound W25 and W45) shorter should be the distance between the probe of the particular vesicle with the Trp of the mutant due to strong interaction.

Fig. 3B shows a plot of FRET intensity (I-I0)/I0 for rP172 Trp mutants in the presence of lipid vesicles. The FRET signal shown is calculated as I–I0, where I is the intensity at 520 nm and I0 is the intensity for a solution of the lipid alone, without protein. The plots of FRET intensity shown are maximal changes observed at a lipid/protein ratio of 20:1. Higher intensity indicates closer interactions. The relatively high FRET value (1.84) of rP172-W25 in ACML lipid vesicles showed very clearly that the N-terminal region of rP172 had much higher affinity towards ACML than POPG at pH 8.0 (0.77) (Fig 3B).

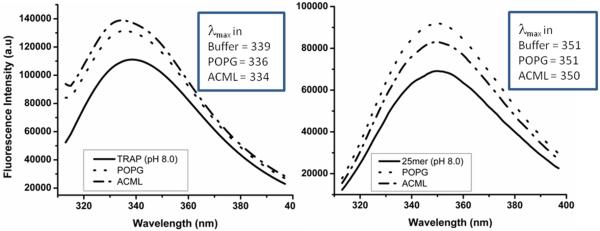

Addition of POPG or ACML to the C-terminal 25-mer synthetic peptide that encompasses the W161 area (black underlined in Fig 1A) did not cause any shift in the fluorescence spectra (Fig 4B) while 45 amino acid N-terminal TRAP which includes W25 and W45 (red underline in Fig 1A) showed significant blue shifts while interacting with ACML (Δλmax = 5) and POPG (Δλmax = 3) (Fig 4A) with ACML being stronger.

Figure 4.

Fluorescence emission spectra show that TRAP peptide (A) has increased blue shifted λmax values in presence of POPG and ACML when compared with C-terminal 25mer peptide (B).

4. Discussion

In order to give insight into the interactions of amelogenin containing enamel extracellular matrix with ameloblast cells, we investigated binding of a series of recombinant Trp mutant amelogenins with liposomes. Site-directed mutagenesis was applied to change the Trp to Tyr residues in such a way that each mutant had only one Trp residue and therefore the membrane-interacting regions of rP172 could be determined. We investigated the fluorescence properties of the Trp residues of rP172-W25, rP172-W45, rP172-W112 and rP172-W161 at pH 8.0, in the presence of POPG and ACML liposomes. At pH 8.0 the amelogenin Trp mutants self-assembled, leading to the burial of N-terminal Trp into a hydrophobic pocket even without liposomes, and hence there was only a subtle difference between the λmax values in the presence and absence of liposomes. The N-terminal has comparatively stronger interactions with the liposomes than the middle or the C-terminal regions.

The NAF curves showed that rP172-W25 and rP172-W45 had lower NAF values (less accessible) than rP172-W112 and rP172-W161, revealing that the former have greater affinity to both the liposomes (figures 3A). The NAF values also revealed that rP172-W112 interacts less with ACML than with POPG. The data became more convincing in light of the FRET analysis (figures 3B) since a FRET value is a measure of the amount of energy transferred from Trp to the dansylchromophore in the liposome. A high FRET value therefore suggests that the Trp is buried in the liposome and is closer to the chromophore. FRET indicated that rP172-W25 and rP172-W45 (representing the N-terminal) have greater interaction with liposomes than the molecules representing the central region (rP172-W112).

Most notably, rP172-W25 showed enhanced interaction with ACML as compared to POPG. Moreover examination of TRAP and C-terminal 25-mer peptides confirmed that neither POPG nor ACML interacted with the C-terminal peptide (Fig 4B) under similar conditions, while the N-terminal TRAP had greater interactions with ACML than with POPG (Fig 4A).

Further investigation is required to demonstrate amelogenin-ameloblast interactions at a molecular level in-vivo. However our present in-vitro studies hints that the N-terminal domain of amelogenin has the intrinsic ability to interact with ameloblast membranes and undergoes significant structural reorganization during the process of binding to them. The functional significance of the N- and C-terminal regions of amelogenin is evident from the fact that their sequences have remained unchanged for 360 million years [8]. Domains at both the N- and C-termini were reported to be involved in amelogenin-amelogenin as well as amelogenin-mineral interactions [22,23,24]. At least two mutations in the amelogenin N-terminal that have been observed in humans (T21I and P41T) are known to cause Amelogenesis imperfecta. In vitro studies have further shown that these mutations or deletion of the N-terminal conserved sequences lead to misfolding and uncontrolled aggregation of amelogenin [17,25,26]. The observation that the thin enamel seen in amelogenin knockout mice lacks prismatic-inter-prismatic architecture supports the notion that matrix-cell binding may be disturbed in the absence of amelogenin [27,28,29]. We suggest that, among other mechanisms, enamel malformation in cases of Amelogenesis Imperfecta with mutations at the amelogenin N-terminal may be the result of defective amelogenin-cell interactions.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

➢ An in vitro approach to explore ameloblast-amelogenin interactions is presented.

➢ An ameloblasts cell membrane model was assembled using a mix of liposomes.

➢ Intrinsic fluorescence of tryptophan and fluorescence resonance energy transfer techniques were utilized.

➢ We report that amelogenin has a strong membrane-binding ability via its N-terminal close to W25.

➢ Enamel malformation may be the result of defective amelogenin-cell interactions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Nanobiophysics Core Facility at the University of Southern California for access to circular dichroism and fluorescence spectroscopy. This research was supported by NIH-NIDCR R01 grants; DE-13414 and DE-020099 to JMO.

ABBREVIATION

- AI

Amelogenisis Imperfecta

- POPG

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoglycerol

- POPC

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylsn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPA

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylsn-glycero-3-phosphate

- POPS

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine

- POPI

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoylsn-glycero-3-phosphoinositol

- POPS

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-Lserine

- POPE

1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- TRAP

Tyrosine Rich Amelogenin Polypeptides

- ACML

Ameloblast Cell Membrane-mimicking Lipid vesicles

- NAF

Net Accessibility Factor

- FRET

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer

- CD

Circular Dichroism

- SUV

Small Unilamellar Vesicles

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

We declare no conflict of interest between the authors or with any institution in relation to the contents of this communication.

References

- [1].Chai H, Lee JJ, Constantino PJ, Lucas PW, Lawn BR. Remarkable resilience of teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7289–7293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902466106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Paine ML, White SN, Luo W, Fong H, Sarikaya M, Snead ML. Regulated gene expression dictates enamel structure and tooth function. Matrix Biology. 2001;20:273–292. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hoang AM, Klebe RJ, Steffensen B, Ryu OH, Simmer JP, Cochran DL. Amelogenin is a cell adhesion protein. J Dent Res. 2002;81:497–500. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Moradian-Oldak J. Protein-mediated enamel mineralization. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:1996–2023. doi: 10.2741/4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gibson CW, Kucich U, Collier P, Shen G, Decker S, Bashir M, Rosenbloom J. Analysis of amelogenin proteins using monospecific antibodies to defined sequences. Connect Tissue Res. 1995;32:109–114. doi: 10.3109/03008209509013711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hart PS, Aldred MJ, Crawford PJM, Wright NJ, Hart TC, Wright JT. Amelogenesis imperfecta phenotype-genotype correlations with two amelogenin gene mutations. Arch Oral Biol. 2002;47:261–265. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(02)00003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Snead ML, Zeichner-David M, Chandra T, Robson KJ, Woo SL, Slavkin HC. Construction and identification of mouse amelogenin cDNA clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:7254–7258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.23.7254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sire JY, Delgado S, Fromentin D, Girondot M. Amelogenin: lessons from evolution. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Delak K, Harcup C, Lakshminarayanan R, Sun Z, Fan YW, Moradian-Oldak J, Evans JS. The Tooth Enamel Protein, Porcine Amelogenin, Is an Intrinsically Disordered Protein with an Extended Molecular Configuration in the Monomeric Form. Biochemistry. 2009;48:2272–2281. doi: 10.1021/bi802175a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Chen CL, Bromley KM, Moradian-Oldak J, DeYoreo JJ. In situ AFM Study of Amelogenin Assembly and Disassembly Dynamics on Charged Surfaces Provides Insights on Matrix Protein Self-Assembly. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:17406–17413. doi: 10.1021/ja206849c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lakshminarayanan R, Moradian-Oldak J, editors. Intrinsic disorder in Amelogenin. Bentham science publishers Ltd; Oak Park, IL, Paris: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moradian-Oldak J, Bouropoulos N, Wang LL, Gharakhanian N. Analysis of self-assembly and apatite binding properties of amelogenin proteins lacking the hydrophilic C-terminal. Matrix Biology. 2002;21:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beniash E, Simmer JP, Margolis HC. The effect of recombinant mouse amelogenins on the formation and organization of hydroxyapatite crystals in vitro. J Struc Biol. 2005;149:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lu JX, Xu YS, Shaw WJ. Phosphorylation and Ionic Strength Alter the LRAP-HAP Interface in the N-Terminus. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2196–2205. doi: 10.1021/bi400071a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chandrababu KB, Dutta K, Lokappa SB, Ndao M, Evans JS, Moradian-Oldak J. Structural adaptation of tooth enamel protein amelogenin in the presence of SDS micelles. Biopolymers . 2013 doi: 10.1002/bip.22415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lokappa SB, Chandrababu K. Balakrishna, Dutta K, Perovic I, Evans J. Spencer, Moradian-Oldak J. Interactions of amelogenin with phospholipids. Biopolymers. 2015;103:96–108. doi: 10.1002/bip.22573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bromley KM, Kiss AS, Lokappa SB, Lakshminarayanan R, Fan D, Ndao M, Evans JS, Moradian-Oldak J. Dissecting amelogenin protein nanospheres: characterization of metastable oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34643–34653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.250928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Goldberg M, Septier D. Phospholipids in amelogenesis and dentinogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2002;13:276–290. doi: 10.1177/154411130201300305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Stern VO, Volmer M. On the quenching-time of fluorescence. Physikalische Zeitschrift. 1919;20:183–188. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lakshminarayanan R, Bromley KM, Lei YP, Snead ML, Moradian-Oldak J. Perturbed amelogenin secondary structure leads to uncontrolled aggregation in amelogenesis imperfecta mutant proteins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:40593–40603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.131136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Paine ML, Lei YP, Dickerson K, Snead ML. Altered amelogenin self-assembly based on mutations observed in human X-linked amelogenesis imperfecta (AIH1) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17112–17116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Paine ML, Snead ML. Protein interactions during assembly of the enamel organic extracellular matrix. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:221–227. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Moradian-Oldak J, Jimenez I, Maltby D, Fincham AG. Controlled proteolysis of amelogenins reveals exposure of both carboxy- and amino-terminal regions. Biopolymers. 2001;58:606–616. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(200106)58:7<606::AID-BIP1034>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shaw WJ, Campbell AA, Paine ML, Snead ML. The COOH terminus of the amelogenin, LRAP, is oriented next to the hydroxyapatite surface. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40263–40266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Moradian-Oldak J, Paine ML, Lei YP, Fincham AG, Snead ML. Self-assembly properties of recombinant engineered amelogenin proteins analyzed by dynamic light scattering and atomic force microscopy. Journal of Structural Biology. 2000;131:27–37. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lakshminarayanan R, Moradian-Oldak J. Intrinsic disorder in Amelogenin. In: Goldberg M, editor. Amelogenins: Multifaceted Proteins for Dental and Bone Formation and Repair. Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.; Oak Park, IL, Paris: 2010. pp. 106–132. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gibson CW, Kulkarni AB, Wright JT. The use of animal models to explore amelogenin variants in amelogenesis imperfecta. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;181:196–201. doi: 10.1159/000091381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pugach MK, Suggs C, Li Y, Wright JT, Kulkarni AB, Bartlett JD, Gibson CW. M180 Amelogenin Processed by MMP20 is Sufficient for Decussating Murine Enamel. J Dent Res. 2013;92:1118–1122. doi: 10.1177/0022034513506444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gibson CW, Li Y, Suggs C, Kuehl MA, Pugach MK, Kulkarni AB, Wright JT. Rescue of the murine amelogenin null phenotype with two amelogenin transgenes. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119(Suppl 1):70–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.