Abstract

Objectives

Patients with oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) have distinct risk factor profiles reflected in the human papillomavirus (HPV) status of their tumor, and these profiles may also be influenced by factors related to socioeconomic status (SES). The goal of this study was to describe the socioeconomic characteristics of a large cohort of patients with OPC according to HPV status, smoking status, and sexual behavior.

Materials and Methods

Patients with OPC prospectively provided information about their smoking and alcohol use, socioeconomic characteristics, and sexual behaviors. HPV status was determined by a composite of immunohistochemistry for p16 expression, HPV in situ hybridization, and PCR assay in 356 patients. Standard descriptive statistics and logistic regression were used to compare socioeconomic characteristics between patient subgroups.

Results

Patients with HPV-positive OPC had higher levels of education, income, and overall SES. Among patients with HPV-positive OPC, never/light smokers had more than 5 times the odds of having at least a bachelor’s degree and being in the highest level of SES compared with smokers. Patients with HPV-positive OPC and those with higher levels of education and SES had higher numbers of lifetime any and oral sex partners, although not all of these differences were significant.

Conclusion

Socioeconomic differences among subgroups of OPC patients have implications for OPC prevention efforts, including tobacco cessation, behavior modification, and vaccination programs.

Keywords: Human papillomavirus, oropharyngeal cancer, head and neck neoplasms, demography, socioeconomic factors, head and neck/oral cancers, behavioral epidemiology, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Two epidemiologically and clinically distinct forms of oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) exist: one strongly associated with smoking and alcohol use and the other strongly associated with prior human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. While the incidence of HPV-negative OPC declined by 50% between 1988 and 2004, the incidence of HPV-positive OPC increased by 225% during the same period [1]. These incidence trends correspond to changes in smoking and sexual behaviors that have occurred over the last five decades [2]. Smoking prevalence has decreased significantly since the 1964 Surgeon General’s warning about the dangers of tobacco use, and the decrease in smoking prevalence has corresponded with a decrease in the incidence of HPV-negative OPC [2]. At the same time, changes in sexual behavior, in particular increased oral sexual activity in certain demographic groups, are likely responsible for the increase in HPV-positive OPC incidence [3–7].

Patients with OPC have distinct risk factor profiles depending on the HPV status of their tumors [8]]. Sexual activity and marijuana exposure are independently associated with HPV-positive cancers, while tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, and poor oral hygiene are associated with HPV-negative cancers [8]. Also potentially associated with HPV-positive OPC are factors related to socioeconomic status (SES), such as higher income and higher education level [8, 9]. In addition to having distinct risk factor profiles, patients with HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC have distinct survival outcomes, including greatly increased 5-year survival for patients with HPV-positive tumors [10].

While many patients with HPV-positive OPC are never smokers or light smokers, a subset of patients with HPV-positive OPC is composed of heavier smokers. This distinction is important because among patients with HPV-positive OPC, never and light smokers have better survival and lower risk of second primary malignancies than heavier smokers [11]. Given this survival disparity, it is important to determine whether never/light smokers and heavier smokers with HPV-positive OPC have different risk factors, including those related to SES. To our knowledge, there are no published studies of socioeconomic characteristics of OPC patients that group patients by smoking status in addition to HPV status. Therefore, we report the demographic characteristics, especially SES, of a large cohort of patients with OPC according to both tumor HPV status and patient smoking status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

We included patients with histologically confirmed, previously untreated incident squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx who presented to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center during the period from May 1995 through April 2013. The patients were part of a large study of molecular epidemiology of head and neck cancer that was approved by the MD Anderson Institutional Review Board. All patients provided informed consent to participate in the study. Patients prospectively completed a questionnaire regarding their demographic and exposure characteristics (smoking and alcohol use) and provided biological specimens for laboratory testing. Beginning in February 2007, patients upon presentation to the institution were also invited to fill out a self-administered questionnaire, as previously described, about their sexual behavior history [12].

HPV determination

HPV in situ hybridization (ISH) and p16 immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Both HPV ISH and p16 IHC were performed using paraffin-embedded tumor tissue. Both methods have been described elsewhere [13, 14]. HPV ISH was performed with Ventana Inform HPV III probes (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), and p16 IHC was performed with a Bond Max automated immunostainer (Vision BioSystems, San Francisco, CA).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Paraffin-embedded tumor tissue was assessed for the presence of HPV16 DNA. We extracted DNA using a tissue DNA extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) and tested this DNA for the presence of HPV16 DNA using a type-specific PCR-based assay with modification for the E6 and E7 regions [15]. Samples were run in triplicate with positive and negative controls and β-actin as a quality control.

Statistical methods

To determine tumor HPV status, we used an algorithm based on that suggested by Singhi and Westra (Figure 1) [16], which incorporates p16 IHC and HPV ISH. According to the algorithm, p16-negative cases were considered HPV-negative, and p16-positive, HPV ISH-positive cases were considered HPV-positive. In the case of discordance (i.e., p16-positive and HPV ISH-negative), we used PCR as the tie-breaker such that cases negative by PCR were considered HPV-negative and cases positive by PCR were considered HPV-positive.

Figure 1.

HPV status of 356 OPC patients according to p16 IHC, HPV ISH, and PCR results.

We created an SES composite score based on the method of Robert et al (Table 1) [17]. This method divides single-SES indices, such as education and income, into categories based on their distribution. Categories are equally weighed and combined into a single composite index. Although there is no standard method for measuring SES, this method has been used in several studies of cancer [18, 19]. We created categories of income and education level based on their distribution among all patients. We then summed the 2 measures to produce a composite SES measure and grouped the composite measures into 3 categories, low, mid, and high, based on their tertile distribution. We were unable to determine SES status for 65 patients due to missing income data (education was also missing for 45 of these patients). We also performed a subgroup analysis of patients for whom sexual history data were available.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic composite scores based on categories of income and education level. Categories were based on their distribution among all patients.

| Education level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤High School |

Technical School/ Associate’s Degree |

Bachelor’s | Advanced | ||

| Income | <$50,000/yr | Low | Low | Mid | Mid |

| $50,000–$99,999/yr | Low | Mid | Mid | High | |

| ≥$100,000/yr | Mid | Mid | High | High | |

Clinical, demographic, and sexual history variables of interest were analyzed using standard descriptive statistical methods. Differences between groups were analyzed using chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test (when cell frequencies were <5) for categorical variables; Student’s t-test, with adjustment for unequal variances where appropriate, for continuous variables; and a nonparametric test for equality of medians. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using univariate and multivariable logistic regression models to compare demographic factors between patients with HPV-positive OPC and patients with HPV-negative OPC and between patients with HPV-positive OPC with 10 or fewer pack years of smoking (described as “never/light smokers”) and patients with more than 10 pack years of smoking (described as “smokers”). Multivariable models included all variables that were significant in univariate analysis as well as age and pack-years of smoking (except in models for HPV-positive patients as they were grouped based on pack-years).

RESULTS

For 356 patients, we were able to determine tumor HPV status using a composite of p16 IHC, HPV ISH, and PCR. Of these, 315 (88.5%) had HPV-positive OPC, and 41 (11.5%) had HPV-negative OPC (Figure 1). Of the 276 patients with HPV-positive OPC with pack years of smoking available, 175 (63.4%) had 10 or fewer pack years (never/light smokers), and 101 (36.6%) had more than 10 pack years (smokers). Sexual history data was available for 248 patients.

Clinical characteristics

Table 2 shows the clinical characteristics of OPC patients according to tumor HPV status and, among patients with HPV-positive OPC, according to smoking status. Compared to patients with HPV-negative OPC, patients with HPV-positive OPC were significantly less likely to be currently smoking at the time of diagnosis (19% vs. 51%) and were significantly less likely to have a history of more than 10 pack years of smoking (37% vs. 76%). Interestingly, all five patients who were p16 IHC-positive but HPV ISH-negative and PCR-negative, and therefore classified as HPV-negative, were never/light smokers. The majority of patients with both HPV-positive and HPV-negative OPC presented with late-stage disease; however, patients with HPV-positive OPC were significantly more likely to present with small primary tumors. In addition, although these differences were not statistically significant, higher proportions of patients with HPV-positive OPC than of patients with HPV-negative OPC had N category 2b–3 disease, poorly differentiated/non-keratinizing tumors, and Kaplan-Feinstein Comorbidity Index scores indicating no or mild comorbidity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of OPC patients by tumor HPV status determined by p16 expression and ISH with or without PCR and by smoking status (N=356)a

| All patients | HPV-positive patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HPV- positive (N=315) |

HPV- negative (N=41) |

P | Never/light smokers N=175 |

Smokers N=101 |

P |

| Smoking status | <.001 | <.001b | ||||

| Never | 115 (41.2) | 7 (18.9) | 115 (65.7) | 0 | ||

| Former | 110 (39.4) | 11 (29.7) | 48 (27.4) | 60 (59.4) | ||

| Current | 54 (19.4) | 19 (51.4) | 12 (6.9) | 41 (40.6) | ||

| Missing | 36 | 4 | ||||

| Pack years of smoking | <.001 | -- | ||||

| ≤10 | 175 (63.4) | 9 (24.3) | 175 (100) | 0 | ||

| >10 | 101 (36.6) | 28 (75.7) | 0 | 101 (100) | ||

| Missing | 39 | 4 | ||||

| Alcohol use | .763 | .111 | ||||

| Never | 76 (27.5) | 9 (24.3) | 55 (31.6) | 21 (20.8) | ||

| Former | 74 (26.8) | 12 (32.4) | 41 (23.6) | 32 (31.7) | ||

| Current | 126 (45.7) | 16 (43.2) | 78 (44.8) | 48 (47.5) | ||

| Missing | 39 | 4 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Subsite | .063b | .563b | ||||

| Tonsil | 172 (54.6) | 22 (53.7) | 93 (53.1) | 58 (57.4) | ||

| Base of tongue | 139 (44.1) | 16 (39.0) | 80 (45.7) | 41 (40.6) | ||

| Other | 4 (1.3) | 3 (7.3) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.0) | ||

| TNM stage | 1.0b | .747 | ||||

| I–II | 22 (7.0) | 3 (7.3) | 14 (8.0) | 7 (6.9) | ||

| III–IV | 293 (93.0) | 38 (92.7) | 161 (92.0) | 94 (93.1) | ||

| T category | .006 | .119 | ||||

| 1–2 | 227 (72.1) | 21 (51.2) | 133 (76.0) | 68 (67.3) | ||

| 3–4 | 88 (27.9) | 20 (48.8) | 42 (24.0) | 33 (32.7) | ||

| N category | .487 | .685 | ||||

| 0–2a | 91 (28.9) | 14 (34.2) | 49 (28.0) | 26 (25.7) | ||

| 2b–3 | 224 (71.1) | 27 (65.9) | 126 (72.0) | 75 (74.3) | ||

| Differentiation | .135 | .338 | ||||

| Well or moderately differentiated/keratinizing | 94 (32.5) | 17 (44.7) | 50 (31.1) | 34 (37.0) | ||

| Moderately poorly or poorly differentiated/non-keratinizing | 195 (67.5) | 21 (55.3) | 111 (68.9) | 58 (63.0) | ||

| Missing | 26 | 3 | 14 | 9 | ||

| Kaplan-Feinstein Comorbidity Index category | 0.136 | .368 | ||||

| None or mild | 285 (90.5) | 34 (82.9) | 163 (93.1) | 91 (90.1) | ||

| Moderate or severe | 30 (9.5) | 7 (17.1) | 12 (6.9) | 10 (9.9) | ||

Values in table are number of patients (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Fisher’s exact test.

Among patients with HPV-positive OPC, we did not see significant differences with respect to clinical characteristics between never/light smokers and smokers, but higher proportions of never/light smokers than of smokers presented with smaller primaries and poorly differentiated/non-keratinizing tumors (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics

Table 3 shows the demographic characteristics of patients with OPC according to tumor HPV status determined by p16 IHC, HPV ISH, and PCR and, among patients with HPV-positive OPC, according to smoking status. Compared to patients with HPV-negative OPC, patients with HPV-positive OPC were more likely to be male, be white, be currently married, and have higher income, education level, and overall SES, and these differences were all significant in univariate analysis (Table 3). Almost half of the patients with HPV-positive OPC had income above $100,000/year and at least a bachelor’s degree, compared with only one-third of patients with HPV-negative OPC. Moreover, more than half of patients with HPV-negative OPC were in the low SES tertile, whereas only one-quarter of patients with HPV-positive OPC were in the low SES tertile. However, these differences in SES between patients with HPV-positive and negative OPC were not significant after multivariate adjustment (Table 3). Only male sex remained significantly associated with HPV status after adjustment for all other covariates (OR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.1–0.6).

Table 3.

Demographic and SES characteristics of OPC patients by tumor HPV status determined by p16 expression and ISH with or without PCR and by smoking status (N=356)a

| All patients | HPV-positive patients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | HPV-positive (N=315) |

HPV-negative (N=41) |

p | Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI)b |

Never/light smokers (N=175) |

Smokers (N=101) |

p | Crude OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted OR (95% CI)b |

| Age, years | .313 | .001 | ||||||||

| ≤55 | 157 (49.8) | 17 (41.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 93 (53.1) | 45 (44.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| >55 | 158 (50.2) | 24 (58.4) | 0.7 (0.4–1.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.6) | 82 (46.9) | 56 (55.5) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 56 (50–62) | 58 (51–64) | ||||||||

| Sex | .001 | .051 | ||||||||

| Male | 276 (87.6) | 28 (68.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 149 (85.1) | 94 (93.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Female | 39 (12.4) | 13 (31.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.2 (0.1–0.6) | 26 (14.9) | 7 (6.9) | 2.3 (1.0–5.6) | 3.7 (1.3–11.1) | ||

| Ethnicity | .034 | .525 | ||||||||

| White | 287 (91.1) | 33 (80.5) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 160 (91.4) | 90 (89.1) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Other | 28 (8.9) | 8 (19.5) | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.5 (0.2–1.4) | 15 (8.6) | 11 (10.9) | 0.8 (0.3–1.7) | 0.8 (0.3–2.0) | ||

| Marital status | .043 | .176 | ||||||||

| Currently married | 218 (79.6) | 24 (64.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 142 (82.1) | 76 (75.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Never/formerly married | 56 (20.4) | 13 (35.1) | 0.5 (0.2–1.0) | 0.8 (0.3–2.0) | 31 (17.9) | 25 (24.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | ||

| Missing | 41 | 4 | 2 | 0 | ||||||

| Income/year | .052 | .005 | ||||||||

| <$50,000 | 55 (21.4) | 13 (38.2) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 25 (15.2) | 30 (32.3) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| $50,000–$99,999 | 79 (30.7) | 11 (32.4) | 1.7 (0.7–4.1) | 0.9 (0.3–2.6) | 52 (31.7) | 27 (29.0) | 2.3 (1.1–4.7) | 1.6 (0.7–3.6) | ||

| ≥$100,000 | 123 (47.9) | 10 (29.4) | 2.9 (1.2–7.0) | 1.3 (0.4–4.2) | 87 (53.1) | 36 (38.7) | 2.9 (1.5–5.6) | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) | ||

| Missing | 58 | 7 | .600c | 11 | 8 | .575c | ||||

| Education level | .002 | <.001 | ||||||||

| High school or GED or less | 65 (23.7) | 19 (51.4) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 25 (14.5) | 40 (39.6) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Technical or vocational school | 85 (31.0) | 6 (16.2) | 4.1 (1.6–11.0) | 2.8 (1.0–8.4) | 52 (30.1) | 33 (32.7) | 2.5 (1.3–4.9) | 2.0 (1.0–4.1) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or greater | 124 (45.3) | 12 (32.4) | 3.0 (1.4–6.6) | 1.2 (0.4–3.2) | 96 (55.5) | 28 (27.7) | 5.5 (2.9–10.5) | 5.2 (2.5–10.8) | ||

| Missing | 41 | 4 | .638c | 2 | 0 | <.001c | ||||

| SES composite | .003 | <.001 | ||||||||

| Q1 (low) | 65 (25.3) | 18 (52.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 27 (16.5) | 38 (40.9) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Q2 (mid) | 104 (40.5) | 7 (20.6) | 4.1 (1.6–10.4) | 2.6 (1.0–7.0) | 67 (40.9) | 37 (39.8) | 2.5 (1.3–4.8) | 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | ||

| Q3 (high) | 88 (34.2) | 9 (26.5) | 2.7 (1.1–6.4) | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) | 70 (42.7) | 18 (19.4) | 5.5 (2.7–11.2) | 5.3 (2.5–11.3) | ||

| Missing | 58 | 7 | .672c | 11 | 8 | <.001c | ||||

GED, graduate equivalency degree; IQR, interquartile range.

Values in table are number of patients (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Adjusted for all other variables and pack years of smoking (SES composite not adjusted for income/education level).

P for trend.

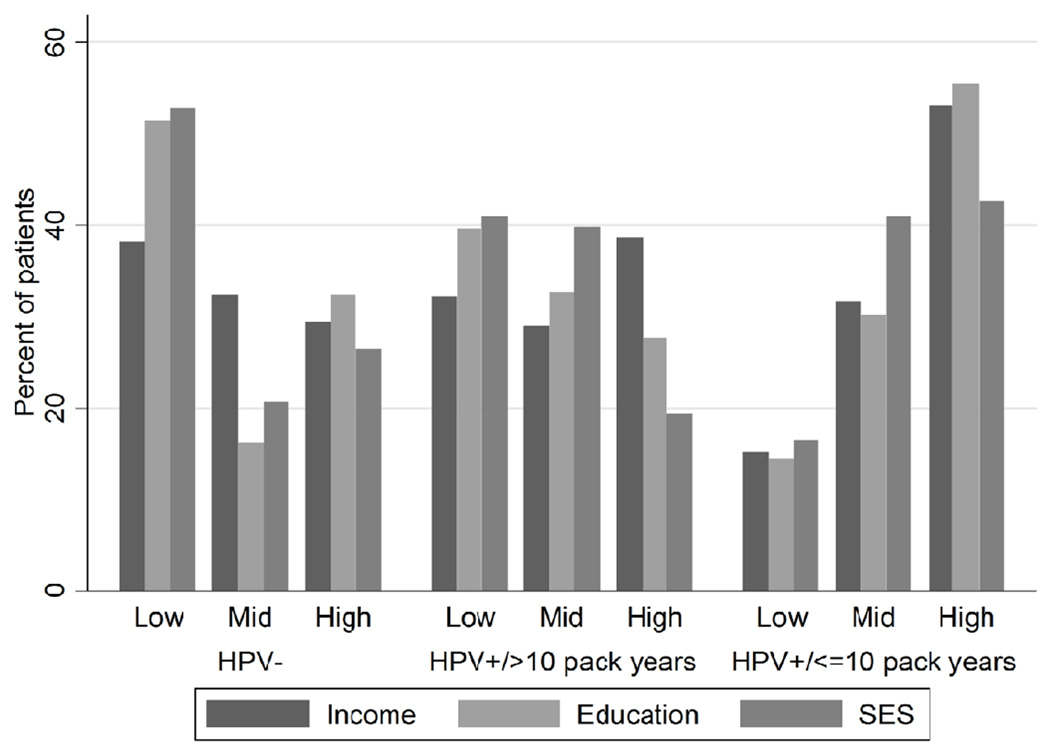

Among patients with HPV-positive OPC, never/light smokers were more likely to be younger, be female, and have higher income, higher education level, and higher overall SES (Table 3, Figure 2). In particular, we observed a significant trend for higher education level and overall SES among never/light smokers (P for trend<0.001 for both measures). Compared to smokers, never/light smokers had more than 5 times the odds of having at least a bachelor’s degree and being in the high SES group, and these associations remained after multivariate adjustment (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of income, education, and SES among OPC patients. Categories of income are: low, <$50,000; mid, $50,000–$99,999; high, ≥$100,000. Categories of education are: low, high school or GED or less; mid, technical or vocational school; high, Bachelor’s degree or greater. Categories of SES are: low, lowest one-third; mid, middle one-third; high, highest one-third. GED, graduate equivalency degree. Highlights SES characteristics of OPC patients are described by HPV and smoking status

Sexual history

Table 4 shows sexual behaviors among OPC patients according to tumor HPV status and demographic characteristics. As expected, patients with HPV-positive OPC had higher mean number of lifetime any (oral, anal, and vaginal) sex partners and oral sex partners than patients with HPV-negative OPC (p=.009 and p=.049, respectively; Table 4). This was mainly due to smokers with HPV-positive OPC, who had a significantly higher mean number of lifetime any sex and oral sex partners than did never/light smokers with HPV-positive OPC (p=.026 and p=.037, respectively; Table 4). White patients had a higher mean number of oral sex partners than did patients of other races (p=.002; data not shown), and never or formerly married patients had higher median number of lifetime any and oral sex partners than did currently married patients (p=.020 and p=.007, respectively; data not shown). We did not observe a significant difference by income level in lifetime number of either any or oral sex partners. Patients with higher education level had a higher mean and median number of lifetime any sex partners (mean, p=.008 and median, p=.070; Table 4). Although patients with higher education level also had a higher mean number of lifetime oral sex partners, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Likewise, patients with higher SES status had significantly more lifetime any sex partners but not oral sex partners. When stratified by SES, patients with HPV-positive OPC in the mid or high SES group had a significantly higher number of mean lifetime any sex partners than did those in the low SES group (p=.014; Table 4). Because sexual behavior reporting is strongly confounded by sex [20], we also analyzed the data stratified by sex and found that the trends in behavior noted above were principally apparent among men (data not shown).

Table 4.

Sexual behaviors of OPC patients with tumor HPV status determined by p16 expression and ISH with or without PCR (N=248)

| Lifetime any sex partnersa | Lifetime oral sex partners | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Pb | Median (IQR) | p | Mean(SD) | Pb | Median (IQR) | p | |

| HPV status | .009 | .070 | .049 | .003 | ||||

| Positive | 23.7 (38.9) | 10 (5–20) | 12.8 (25.9) | 4 (2–10) | ||||

| Negative | 11.3 (14.7) | 6.5 (3–10) | 6.0 (12.3) | 2 (1–3) | ||||

| HPV-positive | .026 | .070 | .037 | .117 | ||||

| Never/light smokers | 17.0 (26.7) | 8.5 (4–20) | 8.4 (13.8) | 4 (2–10) | ||||

| Smokers | 34.7 (53.7) | 12 (6–30) | 19.3 (37.7) | 6 (2–16) | ||||

| HPV-positive | .014 | .073 | .116 | .269 | ||||

| Low SES | 13.5 (16.8) | 7 (5–14) | 8.3 (12.4) | 4 (1–10) | ||||

| Mid or high SES | 25.9 (42.7) | 10 (5–25) | 13.5 (27.7) | 5 (2–10.5) | ||||

| Income/year | .785 | .293 | .825 | .267 | ||||

| <$50,000 | 24.8 (50.1) | 6.5 (4–16) | 13.3 (35.8) | 3.5 (1.5–10) | ||||

| ≥$50,000 | 22.2 (35.4) | 10 (5–25) | 11.8 (21.8) | 4 (2–10) | ||||

| Education level | .008 | .070 | .358 | .110 | ||||

| High school or GED or less | 13.0 (15.9) | 6 (4–16) | 9.4 (14.6) | 3 (1–10) | ||||

| Greater than high school or GED | 24.6 (41.5) | 10 (5–25) | 12.2 (26.6) | 4 (2–10) | ||||

| SES | .006 | .020 | .118 | .102 | ||||

| Low | 12.6 (16.6) | 6 (4–11) | 8.3 (13.3) | 3 (1–8.5) | ||||

| Mid or high | 25.4 (41.9) | 10 (5–25) | 13.1 (27.2) | 4 (2–10) | ||||

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range.

Any sex includes oral, vaginal, and anal sex.

Student’s t-test adjusted for unequal variances.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that patient SES factors were associated with tumor HPV status, patient smoking status, and sexual behavior. In particular, patients with HPV-positive OPC had higher income and education level than patients with HPV-negative OPC, and among patients with HPV-positive OPC, never/light smokers had the highest income and education levels. Sexual exposures were more common among patients with HPV-positive tumors, particularly smokers with HPV-positive tumors, and sexual exposures were more common among patients with higher education level and SES.

Our findings are consistent with previously reported findings that tobacco-related OPC is associated with low SES, while HPV-related OPC appears to be associated with higher SES [8]. Our study also adds to these previously reported findings by showing that among patients with HPV-related OPC, there are significant differences between never/light smokers and smokers. The pattern of association of low SES with tobacco-related OPC and high SES with HPV-related OPC may be due to differences in sexual behavior among different SES groups. Sexual behavior has been associated with oral HPV infection and HPV-positive OPC, and individuals with high number of lifetime sex partners or oral sex partners are at increased risk of OPC [21, 22]. Furthermore, population-based surveys from the 1990s showed that SES is associated with sexual behaviors [23–25]. In a subgroup analysis of sexual history data, we found that patients overall with HPV-positive OPC tended to have greater mean number of lifetime any sex and oral sex partners than HPV-negative patients, and that smokers with HPV-positive OPC tended to have higher number of partners than never/light smokers with HPV-positive OPC. This is consistent with previous research showing that smokers were more likely than nonsmokers to engage in more risky sexual behaviors [26]. While health education efforts in the young correctly focus much effort on tobacco avoidance and on risks associated with sex, these results point to a subgroup of the population at risk for more high-risk behaviors who may benefit from more intensive behavior modification interventions.

In this study, we found that patients with HPV-positive OPC were more likely to be white than patients with HPV-negative OPC. Evidence that racial differences exist in the association between sexual behaviors comes from the National Survey of Family Growth and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [27, 28]. Black males reported significantly more lifetime sex partners than white and Hispanic males (median, 8.3, 5.3, and 4.5, respectively); however, white males were more likely to have ever engaged in oral sex than black or Hispanic males (87%, 79%, and 74%, respectively). Additionally, white females were more likely to have ever engaged in oral sex than black or Hispanic females (88%, 75%, and 68%, respectively).

Moreover, we found that patients with higher levels of education and SES had a higher mean number of lifetime any sex partners. Our findings that both SES indicators and sexual behavior are associated with HPV and smoking status among OPC patients are consistent with other studies that have found that patterns of sexual behavior vary among men and women and across levels of SES [23–25, 29, 30]. While women of low SES are more likely to report higher number of sex partners, men of high SES are more likely to report higher numbers of sex partners. In a population-based survey of more than 2,000 adults in the U.S., Leigh et al reported that individuals with some college were more likely to have had 5 or more sex partners in the past 5 years than individuals without a high school degree [23].

Further evidence that SES and sexual behavior are associated comes from a pooled case-control study from the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium, which showed that lifetime number of sex partners and the likelihood of ever having had oral sex increased with education level among controls [29]. Furthermore, higher number of lifetime sex partners and oral sex partners both increased the risk for OPC but not tumors at other head and neck sites [29]. Additionally, in a case-control study, Gillison et al found that patients with HPV-positive head and neck cancer were more likely to be currently married and patients with HPV-negative head and neck cancer were less likely to have annual income of $50,000 or greater or to have a high school degree compared with cancer-free controls [8].

This study has several strengths. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study of SES in OPC patients that took into account not only HPV status but also smoking status. This is important as there seem to be 3 distinct groups of patients with different characteristics and outcomes: patients with HPV-positive OPC with little or no smoking history, who have excellent survival rates; patients with HPV-negative OPC with significant smoking history, who have a poor prognosis; and patients with HPV-positive OPC with significant smoking history, who have intermediate survival outcomes [11]. Second, we analyzed data from a prospectively recruited cohort of patients, which minimizes selection biases, whereas previously reported clinical trials suffer from selection bias related to stringent inclusion criteria.

This study also has some limitations. First, some misclassification of HPV status may have occurred. When determining HPV status by PCR, we only tested for HPV16. However, this practice is not likely to have resulted in high rates of misclassification as more than 90% of HPV-positive OPCs are positive for type 16 [31]. Moreover, only 6.5% of patients considered HPV-negative by PCR were classified as HPV-positive by the combination of IHC, ISH, and PCR, indicating that few patients were positive for HPV types not picked up by the ISH assay or had false-negative findings on PCR. A second limitation of our study is that selection bias is possible given that only a subset of patients were tested for HPV status. However, there were no set selection criteria for testing, and all patients who have tissue available are tested for HPV, limiting any differential effect of this bias. A third limitation is that other selection biases could also exist because our sample set included only patients presenting to a tertiary cancer center. Consequently, application of these findings to the population more generally should be with caution. Finally, since the majority of patients had HPV-positive OPC, it is possible that decreased study power biased the results toward the null and thereby significant associations were missed.

We found that measures of SES were associated with tumor HPV status and smoking status among OPC patients. We also found, consistent with the literature, that sexual behaviors were associated with HPV-positive OPC as well as SES. Higher number of sex partners and oral sex partners tended to be more common among women with lower SES and men with higher SES. HPV-positive OPC tends to be a disease of middleclass white males and this is precisely the group that is more likely to engage in more risky sexual behavior. Our results add to the evidence that demographic factors are associated with subgroups of patients with OPC stratified by tumor HPV status and patient smoking status. Certain demographic groups may benefit from increased smoking avoidance efforts as well as education on risks associated with certain sexual behaviors. We strongly advocate HPV vaccination in both boys and girls and across all SES groups.

Highlights.

Patients with HPV+ OPC had higher levels of education and income

HPV+ never/light smokers had higher levels of education than HPV+ smokers

SES differences among subgroups of OPC patients have implications for prevention

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephanie Deming for manuscript editing.

Financial support: This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support Grant, CA016672 and National Institutes of Health grant R03 CA128110-01A1 (to E.M.S.). This research was accomplished within the Oropharynx Program at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and funded in part through the Stiefel Oropharyngeal Research Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no financial interests or commercial associations with any of the material contained in the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–4301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ang KK, Sturgis EM. Human papillomavirus as a marker of the natural history and response to therapy of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2012;22:128–142. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner CF, Danella RD, Rogers SM. Sexual behavior in the United States 1930–1990: Trends and methodological problems. Sex Transm Dis. 1995;22:173–190. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernster JA, Sciotto CG, O'Brien MM, Finch JL, Robinson LJ, Willson T, et al. Rising incidence of oropharyngeal cancer and the role of oncogenic human papilloma virus. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:2115–2128. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31813e5fbb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammarstedt L, Lindquist D, Dahlstrand H, Romanitan M, Dahlgren LO, Joneberg J, et al. Human papillomavirus as a risk factor for the increase in incidence of tonsillar cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:2620–2623. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajos N, Bozon M, Beltzer N, Laborde C, Andro A, Ferrand M, et al. Changes in sexual behaviours: From secular trends to public health policies. AIDS. 2010;24:1185–1191. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328336ad52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–420. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D'Souza G, Zhang HH, D'Souza WD, Meyer RR, Gillison ML. Moderate predictive value of demographic and behavioral characteristics for a diagnosis of HPV16-positive and HPV16-negative head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:100–104. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, Xiao W, Westra WH, Trotti A, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–2111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlstrom KR, Tortolero-Luna G, Li G, Wei Q, Sturgis EM. Differences in history of sexual behavior between patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma and patients with squamous cell carcinoma at other head and neck sites. Head Neck. 2011;33:847–855. doi: 10.1002/hed.21550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo M, Baruch AC, Silva EG, Jan YJ, Lin E, Sneige N, et al. Efficacy of p16 and ProExC immunostaining in the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:212–220. doi: 10.1309/AJCP1LLX8QMDXHHO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo M, Gong Y, Deavers M, Silva EG, Jan YJ, Cogdell DE, et al. Evaluation of a commercialized in situ hybridization assay for detecting human papillomavirus DNA in tissue specimens from patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical carcinoma. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:274–280. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01299-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji X, Sturgis EM, Zhao C, Etzel CJ, Wei Q, Li G. Association of p73 G4C14-to-A4T14 polymorphism with human papillomavirus type 16 status in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck in non-Hispanic whites. Cancer. 2009;115:1660–1668. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhi AD, Westra WH. Comparison of human papillomavirus in situ hybridization and p16 immunohistochemistry in the detection of human papillomavirus-associated head and neck cancer based on a prospective clinical experience. Cancer. 2010;116:2166–2173. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert SA, Strombom I, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, McElroy JA, Newcomb PA, et al. Socioeconomic risk factors for breast cancer: Distinguishing individual- and community-level effects. Epidemiology. 2004;15:442–450. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000129512.61698.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du XL, Fang S, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Aragaki C, Cormier JN, et al. Racial disparity and socioeconomic status in association with survival in older men with local/regional stage prostate carcinoma: findings from a large community-based cohort. Cancer. 2006;106:1276–1285. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du XL, Sun CC, Milam MR, Bodurka DC, Fang S. Ethnic differences in socioeconomic status, diagnosis, treatment, and survival among older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008;18:660–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiederman MW. The truth must be in here somewhere: Examining the gender discrepancy in selfreported lifetime number of sex partners. J Sex Res. 1997;34:375–386. [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Souza G, Agrawal Y, Halpern J, Bodison S, Gillison ML. Oral sexual behaviors associated with prevalent oral human papillomavirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1263–1269. doi: 10.1086/597755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.D'Souza G, Cullen K, Bowie J, Thorpe R, Fakhry C. Differences in oral sexual behaviors by gender, age, and race explain observed differences in prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leigh BC, Temple MT, Trocki KF. The sexual behavior of US adults: Results from a national survey. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1400–1408. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.10.1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seidman SN, Mosher WD, Aral SO. Women with multiple sexual partners: United States, 1988. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1388–1394. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.10.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melbye M, Biggar RJ. Interactions between persons at risk for AIDS and the general population in Denmark. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:593–602. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Visser RO, Rissel CE, Smith AM, Richters J. Sociodemographic correlates of selected health risk behaviors in a representative sample of Australian young people. Int J Behav Med. 2006;13:153–162. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1302_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosher WD, Chandra A, Jones J. Sexual behavior and selected health measures: Men and women 15–44 years of age, United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2005;(362):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leichliter JS, Chandra A, Liddon N, Fenton KA, Aral SO. Prevalence and correlates of heterosexual anal and oral sex in adolescents and adults in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1852–1859. doi: 10.1086/522867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heck JE, Berthiller J, Vaccarella S, Winn DM, Smith EM, Shan'gina O, et al. Sexual behaviours and the risk of head and neck cancers: A pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39:166–181. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drolet M, Boily MC, Greenaway C, Deeks SL, Blanchette C, Laprise JF, et al. Sociodemographic inequalities in sexual activity and cervical cancer screening: Implications for the success of human papillomavirus vaccination. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:641–652. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaturvedi AK. Beyond cervical cancer: Burden of other HPV-related cancers among men and women. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(4 Suppl):S20–S26. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]