Abstract

The BROTHERS Project (HPTN 061) was established to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a multi-component intervention among African American MSM to reduce HIV incidence. The goal of this analysis was to determine if the sexual partner referral approach used in HPTN 061 broadened the reach of recruitment with regards to characteristics associated with higher infection rates and barriers to quality health care. Overall, referred sexual partners had notable structural barrier differences in comparison to community-recruited participants: lower income, less education, higher unemployment, HIV positive diagnosis, incarceration history, and no health insurance. The study’s findings pose implications for utilizing the sexual partner referral approach in reaching African American MSM who may not be accessed by traditional recruitment methods or who are well-integrated in health care systems.

Keywords: HIV, African American MSM, Referrals, Recruitment

Introduction

The CDC in a recent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR, 2014) stated that the best way to keep those with HIV virally suppress, thereby reducing opportunities for transmission and new infection, is to engage HIV infected person in each phase along the care continuum (from diagnosis to periodic routine care) [1]. Also in the literature, researchers also suggest that high risk populations, which are often hard to reach, should be encouraged to seek, test, be treated and retained (STTR strategy) in order to capitalize on the current advancements in medical science [2]. But for some Americans, health care is not reaching those most in need. It has been reported that about 16 % of HIV infected African American men who have sex with men (MSM) are virally suppressed, as compared to 34 % of white MSM, an indication of disparities along the HIV care continuum [3]. African American MSM also endure greater infection rates, reported to be seven times more likely to be newly HIV infected as compared to their white counterparts [4]. Such disproportionate rates represent a critical public health problem in the United States, given the strides in medical science, care and technologies as well as our understanding of prevention efforts like Pre-exposure and Post-exposure prophylaxis. Recent studies have found high HIV infection rates, particularly among young African American MSM [5, 6]. HIV prevention research has shown that high rates of HIV among African American MSM may in part be attributed to younger sexual debut [7], older sexual partners [8], sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, sexual mixing within African American networks that facilitate HIV transmission [8–11], infrequent HIV testing [12], and undetected or late diagnosis of HIV infection [13, 14]. These issues are compounded by African American MSM poor access to quality medical care and HIV antiretroviral therapies [15, 16].

Barriers to health care access can occur for both sexual and racial/ethnic minorities including: structural barriers to care such as a lack of insurance [10, 17], reluctance to seek care because of high risk behaviors and/or expression of sexuality or gender [18, 19], and perceived racial discrimination and conspiracy thoughts regarding diseases (such as HIV) and about care regarding those diseases [20–22]. In addition, stigma is known to be a negative force that can separate those with diseases or at-risk for acquiring diseases from care settings where HIV positive people, for example, can be subjected to hostility and discrimination [23]. Thus, African American MSM who may be marginalized within their own community, who are poorer, have less education, and more likely to express gender or sexual variance within the context of homosexuality may interpret research interventions as spaces that are not culturally appropriate for them. African American MSM may also be less inclined to engage in MSM venues where recruitment for research often occurs because these venues are not as welcoming to them as their white counter-parts [24].

Expanding recruitment by using participant referrals can be effective in broadening the reach of HIV-related studies [25, 26]. The use of referrals may allow researchers to enroll subgroups of populations who do not frequent services or other venues, who are not likely engaged by traditional recruiting methods, who are potentially at higher risk of HIV infection and who may have poorer access to quality care [27–29]. In a study cited by the CDC using participant referrals among African American MSM, researchers reported that many African American MSM face socioeconomic challenges preventing access to care and thereby HIV and STI screenings [30].

HPTN 061, The BROTHERS Project, was established to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a multi-component intervention among African American MSM to reduce HIV incidence. HPTN 061 provides the opportunity to examine how effective a participant referral approach was in broadening the reach of recruitment. This analysis aims to determine if referred sexual partners were different than community-recruited participants with regards to characteristics that have been associated with higher infection rates and barriers to quality health care access. These characteristics included: demographics, sexual risk behaviors, health care utilization, conspiracy theories around HIV and composite scores on perceived discrimination, and the use of the project’s Peer Health Navigators (PHNs). Furthermore, to better understand recruitment efforts, community-recruited participants who referred sexual partners were compared to those who did not refer.

Methods

Participants

Between July 2009 and October 2010, 1,553 self-identified black (i.e. African American, Caribbean black, or multiethnic black) men (i.e. a man or male at birth) who were at least 18 years of age and who reported at least one instance of unprotected anal intercourse with a man in the past 6 months participated in HPTN 061 in Atlanta, Boston, Los Angeles, New York City, San Francisco, and Washington DC [5, 31]. The institutional review boards at all participating institutions approved the study. The study recruited men directly from the community or as referred sexual partners of index participants. Index participants were (1) men who were HIV-positive and unaware of their HIV status, (2) men who were HIV-positive and not in care or in care and reported unprotected sex with uninfected partners or partners of unknown status, or (3) initially a random sample of HIV uninfected men in the study. Later, partway through the study, all HIV uninfected men in the study were designated as indexes. For their participation all participants received as much as $100 for their baseline data collection and as much as $50 for follow-up data collections at 6- and 12-months, depending on the study site. In addition, community recruited participants who were categorized as index participants were asked to refer up to five sexual partners who were African American MSM. Community recruited index participants received a range of $5 (in Boston) to $20 (in Los Angeles and Atlanta) per referral. Indexes were given coded cards and instructed to given these coded cards to their sexual referrals for the project. Referrals were then recorded when they turned in the coded cards upon enrollment. Since the study participants included both HIV positive and negative men, referrals were not necessarily aware of the status of the indexes and no names of referrals were shared with indexes. Like the community-recruited participants, referred sexual partners were eligible to participate if they met the eligibility criteria described above.

At each participant’s enrollment visit, eligibility was confirmed and written consent obtained. All participants provided locator information, demographic information and then were asked to complete a behavioral assessment using audio computer-assisted self-interview technology (ACASI). All participants received HIV/STI prevention risk-reduction counseling and testing for HIV, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis. Reactive rapid HIV tests using blood samples were confirmed at study sites by Western blot testing. Quality assurance testing was performed retrospectively at the HPTN Network Laboratory to confirm the HIV infection status of all study participants at enrollment. For participants with low or undetectable HIV RNA who did not report a prior HIV diagnosis, enrollment samples were tested for the presence of antiretroviral drugs after the end of the study; men whose samples contained antiretroviral drugs indicative of antiretroviral therapy were considered to have a prior HIV diagnosis. Any participant who tested positive for any of the infections was referred for appropriate treatment, medical, and social services.

Measures

Demographic characteristics were collected by an interviewer and included measures for age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, education, housing, employment, and income. The additional measure of lifetime experience with incarceration was collected by ACASI. Participants were also asked about their prior experience with research studies. Baseline HIV status by laboratory testing was utilized for the analysis.

Sexual risk and substance use behaviors, also part of the ACASI interview, included early experiences with unwanted sex and in the six months prior to enrollment, the number of partners, the number of new partners, having female partners, had a primary male partner, unprotected (condom-less) receptive and insertive anal intercourse (URAI/UIAI) with male/transgender male partners, and receipt of money, drugs, or other goods or a place to stay for sex. Measures on alcohol use frequency, amount and dependency were derived from the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) in which the answers were recorded on a point system and a total of more than eight was used to indicate an alcohol problem [32]. Questions on other substance use in the six months prior to enrollment included: the use of marijuana, inhaled nitrates, smoked and powder cocaine, and methamphetamines.

Health care utilization questions included measures on whether participants had health insurance, a usual place of health care and HIV testing history. Two additional questions were asked about treatment optimism: “I feel comfortable having unprotected sex because treatments for HIV will continue to improve” and “I feel comfortable having unprotected sex because HIV can be easily managed now”. The answers for these two questions were on a five-point scale ranging from “disagree” to “agree”.

Conspiracy theories about HIV was measured with nine items such as “There is a cure for AIDS, but it is being withheld from the poor” with responses on a five-point, Likert-type scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” with the option of not being aware of the claim in the statement [20]. A composite score was used for this analysis with a range between −18 and 18. Low conspiracy composite scores ranged from −18 to 6 and the high conspiracy composite scores ranged from 7 to 18.

Perceived racism and sexuality discrimination were measured with 28 and 25 items (respectively) as the occurrence of experiences such as “being treated rudely or disrespectfully because of “my race” or “my sexuality” [5, 33, 34]. The extent that the events bothered the participant was measured with a five-point, Likert-type scale from “Not At All” to “Extremely”. For the perceived racial discrimination composite scores ranged from 0 to 140 and those who scored under 95 had a low composite score, while those that had 95–140 had a high composite score. For the perceived sexual discrimination composite score, the range was between 0 and 125, and those who had a score of 84 or less were considered to have a low composite score, while those who had a score of 85–125 had a high composite score.

The use of PHNs was an integral part of the HPTN (061) multi-component intervention. PHNs conducted assessments of participants’ health care history and unmet service needs, and then met with participants over time to implement action plans. For this analysis there were two questions that were examined: whether or not a participant accepted PHN at baseline and how many PHN sessions the participant attended over the course of their participation in the project.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made on six domains: demographics, sexual risk and drug use behaviors, health care utilization, conspiracy theories about HIV and composite scores on perceived discrimination, and the use of the project’s PHNs using Pearson χ2 tests and Fisher’s Exact tests, when cell counts were low. First, referred sexual partners were compared to all community-recruited participants. Next, community-recruited index participants who successfully referred sexual partners were compared to those who did not refer even though they were eligible to do so to determine if there was a bias in those who were successful in referring versus those who were not.

Finally, the community-recruited index participants who successfully referred sexual partners were compared to their sexual partner referrals that enrolled in the program. Generalized estimating equation methods were used to assess associations between characteristics of index participants and characteristics of their referred partners, where multiple partners from the same index were treated as repeated measures and correlations among them were counted for. Analyses were implemented using SAS® version 9.2.

Results

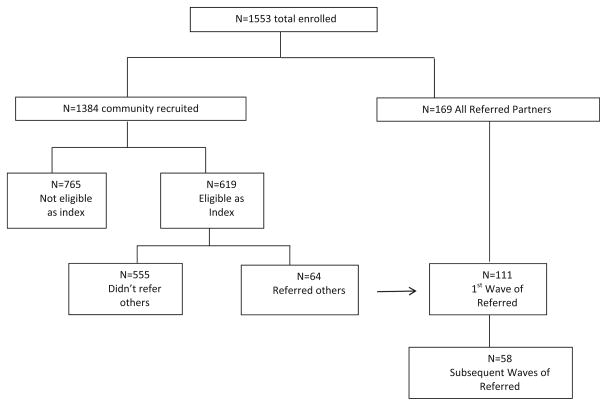

HPTN 061 enrolled a total of 1,553 participants (Fig. 1). Of the total number of participants, 1,384 were recruited directly through the community, of which 765 did not meet the eligibility requirements to recruit sexual network partners and 619 were eligible to recruit sexual network partners (indexes). Of the 619 index participants, 10.3 % or 64 index participants recruited a total of 111 sexual partners. These referred sexual network partners successfully recruited an additional 58 sexual partners into the project. Of the 64 indexes who successfully referred sexual partners: 35 referred 1 sexual partner; 18 referred two sexual partners; 5 referred 3 sexual partners; 5 referred 4 sexual partners; and one referred the maximum cap of 5 sexual partners.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of HPTN 061 participants based on their recruitment methods into the study

Referred Sexual Partner Participants (n = 169) Compared to Community-Recruited Participants (n = 1384)

Compared to the overall community-recruited participants, referred sexual partner participants were more likely to be between the ages of 31–45 (χ2 = 19.99; p <0.001) and less likely to be Latino identified (χ2 = 5.93; p = 0.015) (Table 1). Referred sexual partner participants were also significantly more likely to have less education (χ2 = 22.45; p = <0.001), lower household income (χ2 = 22.29; p <0.001), and to be unemployed (χ2 = 10.48; p = 0.001). Moreover, referred sexual partner participants were more likely to have been incarcerated (χ2 = 8.67; p = 0.003). Referred sexual partner participants in comparison to the overall community-recruited participants were less likely to have participated in a research study before (χ2 = 8.07; p = 0.004) and were more likely to be previously diagnosed as HIV positive at their baseline visit (χ2 = 71.44; p <0.001). Few differences were found on key sexual risk behaviors known to be associated with HIV infection (Table 2). However, a greater percentage of referred sexual partner participants reported having an unwanted sexual experience between the ages of 12–16 (χ2 = 8.69; p = 0.013). No differences were noted with regards to substance use behaviors.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of community-recruited and referred participants and community-recruited participants who did and did not refer

| Community-recruited participants | Referred participants | Test statistic | p value | Participants eligible to refer but did not | Participants eligible to refer and did | Test statistic | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,384 | n = 169 | n = 555 | n = 64 | |||||

| Age | 19.99 | < 0.001 | 5.32 | 0.070 | ||||

| ≤30 | 488 (35 %) | 31 (18 %) | 225 (41 %) | 17 (27 %) | ||||

| 31–45 | 490 (35 %) | 80 (47 %) | 187 (34 %) | 24 (38 %) | ||||

| ≥46 | 406 (29 %) | 58 (34 %) | 143 (26 %) | 23 (36 %) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 5.93 | 0.015 | 1.65 | 0.199 | ||||

| Latino or of hispanic origin | 114 (8 %) | 5 (3 %) | 53 (10 %) | 3 (5 %) | ||||

| Sexual orientation | 2.29 | 0.317 | 1.95 | 0.377 | ||||

| Exclusively homosexual/gay | 408 (30 %) | 51 (31 %) | 184 (34 %) | 24 (38 %) | ||||

| Exclusively bisexual | 380 (28 %) | 53 (33 %) | 139 (25 %) | 11 (17 %) | ||||

| Other | 570 (42 %) | 59 (36 %) | 224 (41 %) | 28 (44 %) | ||||

| Gender identity | 0.0019a | 0.002 | 0.012a | 0.296 | ||||

| Male | 1298 (94 %) | 152 (90 %) | 518 (93 %) | 61 (95 %) | ||||

| Female | 7 (1 %) | 1 (1 %) | 4 (1 %) | 1 (2 %) | ||||

| Transgender | 27 (2 %) | 6 (4 %) | 14 (3 %) | 2 (3 %) | ||||

| Other | 52 (4 %) | 10 (16 %) | 19 (3 %) | 0 (0 %) | ||||

| High school education equivalent or less | 699 (51 %) | 118 (70 %) | 22.45 | < 0.001 | 276 (50 %) | 44 (69 %) | 8.30 | 0.004 |

| Lack stable housing at enrollment | 130 (9 %) | 18 (11 %) | 0.28 | 0.599 | 47 (8 %) | 11 (17 %) | 5.13 | 0.023 |

| Household income | 22.29 | < 0.001 | 13.17 | 0.001 | ||||

| Under $20,000 | 795 (58 %) | 125 (74 %) | 295 (54 %) | 49 (77 %) | ||||

| $20,000–39,999 | 319 (23 %) | 35 (21 %) | 128 (24 %) | 11 (17 %) | ||||

| $40,000+ | 255 (19 %) | 9 (5 %) | 121 (22 %) | 4 (6 %) | ||||

| Currently not working | 936 (68 %) | 135 (80 %) | 10.48 | 0.001 | 364 (66 %) | 53 (83 %) | 7.65 | 0.006 |

| Incarcerated in last 6 months | 798 (59 %) | 116 (71 %) | 8.67 | 0.003 | 308 (57 %) | 41 (64 %) | 1.29 | 0.255 |

| Ever participated in research | 411 (30 %) | 32 (20 %) | 8.07 | 0.004 | 142 (26 %) | 17 (27 %) | 0.02 | 0.880 |

| HIV status at baseline of study | ||||||||

| Refused testing/unknown | 35 (3 %) | 3 (2 %) | 71.44 | < 0.001 | 0 (0 %) | 1 (2 %) | 0.0037 | 0.025 |

| HIV-negative | 1082 (78 %) | 85 (50 %) | 387 (70 %) | 38 (59 %) | ||||

| HIV-positive | 266 (19 %) | 81 (48 %) | 168 (30 %) | 25 (39 %) | ||||

Fisher’s exact test

Table 2.

Sexual risk behaviors and substance use among community-recruited and referred participants and community-recruited participants who did and did not refer

| Community-recruited participants | Referred participants | Test statistic | p value | Participants eligible to refer but did not | Participants eligible to refer and did | Test statistic | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1,384 | n = 169 | n = 555 | n = 64 | |||||

| Any unwanted sexual experiences between the ages of 12–16 years | 406 (30 %) | 60 (37 %) | 8.69 | 0.013 | 164 (30 %) | 23 (37 %) | 1.33 | 0.515 |

| Number of partners in the last 6 months | 5.65 | 0.227 | 4.9 | 0.297 | ||||

| 0 | 11 (1 %) | 3 (2 %) | 6 (1 %) | 0 (0 %) | ||||

| 1–3 | 493 (36 %) | 65 (38 %) | 197 (36 %) | 18 (28 %) | ||||

| 4–8 | 503 (36 %) | 58 (34 %) | 203 (37 %) | 27 (42 %) | ||||

| 9–15 | 221 (16 %) | 19 (11 %) | 90 (16 %) | 8 (13 %) | ||||

| ≥16 | 152 (11 %) | 24 (14 %) | 58 (10 %) | 11 (17 %) | ||||

| In last 6 months | ||||||||

| URAI with male/transgender male partners | 687 (50 %) | 90 (55 %) | 1.03 | 0.311 | 291 (53 %) | 35 (55 %) | 0.03 | 0.856 |

| UIAI with male/transgender male partners | 1023 (75 %) | 118 (72 %) | 0.76 | 0.381 | 405 (74 %) | 50 (78 %) | 0.44 | 0.507 |

| Received money, drugs, or other goods or place to stay to have sex | 295 (22 %) | 39 (24 %) | 0.38 | 0.539 | 103 (19 %) | 19 (30 %) | 3.81 | 0.051 |

| Harmful drinking (AUDIT ≥ 8) | 430 (41 %) | 41 (37 %) | 3.01 | 0.082 | 164 (39 %) | 14 (38 %) | 1.63 | 0.201 |

| Drug use | ||||||||

| Marijuana | 756 (56 %) | 86 (54 %) | 0.33 | 0.567 | 322 (59 %) | 34 (56 %) | 0.27 | 0.603 |

| Inhaled nitrites | 156 (12 %) | 16 (11 %) | 0.21 | 0.649 | 67 (13 %) | 7 (11 %) | 0.18 | 0.670 |

| Cocaine | 342 (26 %) | 42 (27 %) | 0.08 | 0.783 | 126 (24 %) | 17 (27 %) | 0.35 | 0.553 |

| Powder cocaine | 239 (18 %) | 28 (19 %) | 0.0009 | 0.976 | 92 (18 %) | 14 (23 %) | 0.88 | 0.346 |

| Methamphetamine | 127 (10 %) | 10 (7 %) | 1.48 | 0.224 | 40 (8 %) | 6 (10 %) | 0.157 | 0.615 |

There were some differences in comparing the two groups of participants’ utilization of existing health services, treatment optimism, conspiracy theories about HIV, perceived discrimination, and their use of the projects’ PHNs showed some differences (Table 3). A smaller percentage of the referred sexual partner participants in comparison to the community-recruited participants had health insurance (χ2 = 5.41; p = 0.020). Referred sexual partner participants reported being less likely to get care at a private facility (χ2 = 10.39; p = 0.001). Referred sexual partner participants were less likely to have had an HIV test in the last year, as compared to the overall community-recruited participants (χ2 = 17.06; p < 0.001). While no statistically significant differences occurred between the two groups with regards to their distribution of composite scores around HIV conspiracy theories, notable differences existed about their perceptions of discrimination. Referred sexual partner participants were more likely to have low composite scores on perceived racism (χ2 = 4.80; p = 0.028) and perceived sexual discrimination (χ2 = 7.91; p = 0.005) in comparison to community-recruited. No statistically significant difference occurred between the two groups with regards to their acceptance and uptake of the study’s peer health navigation.

Table 3.

Utilization of existing health services, treatment optimism, conspiracy theories about HIV, perceived discrimination, and the use of peer health navigation among community-recruited and referred participants and community-recruited participants who did and did not refer

| Community-recruited participants | Referred participants | Test statistic | p value | Participants eligible to refer but did not | Participants eligible to refer and did | Test statistics | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 1384 | n = 169 | n = 555 | n = 64 | |||||

| Ever HIV tested prior to this study | 1214 (88 %) | 133 (79 %) | 11.61 | < 0.001 | 472 (85 %) | 52 (83 %) | 0.31 | 0.576 |

| Times tested in the last year | 17.06 | < 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.978 | ||||

| 0 | 165 (14 %) | 35 (27 %) | 64 (14 %) | 7 (14 %) | ||||

| 1 | 456 (38 %) | 38 (29 %) | 183 (39 %) | 19 (38 %) | ||||

| 2–4 | 495 (41 %) | 51 (39 %) | 190 (41 %) | 20 (40 %) | ||||

| ≥5 | 84 (7 %) | 6 (5 %) | 30 (6 %) | 4 (8 %) | ||||

| Had health insurance | 849 (61 %) | 88 (52 %) | 5.41 | 0.020 | 365 (66 %) | 31 (48 %) | 7.47 | 0.006 |

| Place of health care | 0.905 | |||||||

| HIV/STD facilities or programs | 59 (4 %) | 14 (8 %) | 5.43 | 0.020 | 17 (3 %) | 3 (5 %) | 0.20a | 0.451 |

| Public health or research facilities | 846(61 %) | 116 (69 %) | 3.61 | 0.058 | 336 (61 %) | 37 (58 %) | 0.18 | 0.673 |

| Privacy facility | 174 (13 %) | 7 (4 %) | 10.39 | 0.001 | 64 (12 %) | 4 (6 %) | 1.63 | 0.201 |

| Comfortable with unprotected sex-treatment will continue to improve | 6.02 | 0.049 | 3.75 | 0.153 | ||||

| Disagree | 946 (69 %) | 101 (60 %) | 384 (70 %) | 37 (58 %) | ||||

| Unsure | 384 (28 %) | 56 (34 %) | 149 (27 %) | 24 (38 %) | ||||

| Agree | 46 (3 %) | 10 (6 %) | 18 (3 %) | 3 (5 %) | ||||

| Comfortable with unprotected sex-care is manageable now | 4.70 | 0.095 | 10.87 | 0.004 | ||||

| Disagree | 990 (72 %) | 105 (64 %) | 400 (73 %) | 35 (56 %) | ||||

| Unsure | 328 (24 %) | 50 (31 %) | 123 (22 %) | 26 (41 %) | ||||

| Agree | 48 (4 %) | 8 (5 %) | 25 (5 %) | 2 (3 %) | ||||

| Conspiracy theories surrounding HIV | 0.64 | 0.424 | 0.1076 | 0.320 | ||||

| Low | 1183(91 %) | 142 (93 %) | 482 (92 %) | 52 (88 %) | ||||

| High | 119 (9 %) | 11 (7 %) | 42 (8 %) | 7 (12 %) | ||||

| Perceived racism score | 4.80 | 0.028 | 5.07 | 0.024 | ||||

| Low (0–94) | 946 (77 %) | 122 (85 %) | 388 (80 %) | 37 (67 %) | ||||

| High (95–140) | 288 (23 %) | 22 (15 %) | 95 (20 %) | 18 (33 %) | ||||

| Perceived sexual discrimination score | 7.91 | 0.005 | 3.03 | 0.082 | ||||

| Low (0–84) | 945 (81 %) | 123 (90 %) | 382 (83 %) | 35 (73 %) | ||||

| High (85–125) | 228 (19 %) | 13 (10 %) | 78 (17 %) | 13 (27 %) | ||||

| Accepted peer health navigation at baseline visit | 717 (54 %) | 77 (52 %) | 0.26 | 0.609 | 312 (56 %) | 38 (59 %) | 0.20 | 0.651 |

| Number PHN visits | 4.11 | 0.128 | 7.11 | 0.029 | ||||

| 0 | 455 (55 %) | 42 (45 %) | 221 (60 %) | 18 (39 %) | ||||

| 1 | 113 (14 %) | 18 (19 %) | 44 (12 %) | 9 (20 %) | ||||

| 2+ | 258 (31 %) | 34 (36 %) | 106 (29 %) | 19 (41 %) |

Fisher’s exact test

Community Recruited Indexes who Successfully Referred Sexual Partners (n = 64) Compared to Community-Recruited Indexes Who did not Refer Sexual Partners (n = 555)

In comparing community-recruited participants who successfully referred sexual partners to those who did not, the community-recruited participants who referred sexual partners had lower education (χ2 = 8.30; p = 0.004), lacked stable housing (χ2 = 5.13; p = 0.023), and more likely unemployed (χ2 = 7.65; p = 0.006). They also were likely to be HIV positive at enrollment (Fisher’s Exact = 0.0037; p = 0.025) (Table 1). No differences in sexual risk and drug use behaviors were found between community-recruited participants who referred participants and those who did not (Table 2).

Community-recruited participants who successfully referred sexual partner participants in comparison those who did not were less likely to have health insurance (χ2 = 7.47; p = 0.006), had a higher composite scores of perceived discrimination based on race (χ2 = 5.04; p = 0.024), and more likely to attend two or more PHN meetings (χ2 = 7.11; p = 0.029).

Community Recruited Indexes Who Successfully Referred Sexual Partners (n = 64) as Compared to their Referred Sexual Partner Participants (n = 111)

Positive HIV status of the community-recruited index participant was associated with positive HIV status of sexual partners who they referred to the study (OR = 11.9; 95 % CI 3.6, 39.6). Younger age of the community-recruited index participant (age ≤ 30) was associated with younger age of referred sexual partners (OR = 4.8; 95 % CI 1.4, 15.7). An index who had STI at enrollment was more likely to refer sexual partners with STI (OR = 4.6; 95 % CI 1.2, 7.8). An index who was incarcerated prior to study enrollment were more likely to refer sexual partners who also had incarceration history (OR = 4.4; 95 % CI 1.3, 14.4). An index with no health insurance coverage was more likely to refer sexual partners who did not have insurance (OR = 4.4; 95 % CI 1.4, 13.6) (Table 4). No statistically significant association was found between community-recruited index participants and referred sexual partners in experience of racism or sexual discrimination, education, reported URAI, or acceptance of PHN service.

Table 4.

Community recruited indexes who successfully referred sexual partners (n = 64) as compared to their referred sexual partner participants (n = 111)

| Index participant with at least one referred partner who was | Then the Index was also likely to be | OR (95 % CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Was HIV+ at baseline | HIV+ | 11.9 (3.6, 39.6) |

| Was ≤ 30 years old | ≤ 30 | 4.8 (1.4, 15.7) |

| Had an STI at enrollment | Yes | 4.6 (1.2, 17.8) |

| Was ever incarcerated | Yes | 4.4 (1.3, 14.4) |

| Had health insurance | Yes | 4.4 (1.4, 13.6) |

| High rates of experienced racism | Experiencing racism | 2.2 (0.4, 11.3) |

| Having some college or above education | Some College | 1.6 (0.5,4.6) |

| Reported URAI | Yes | 1.4 (0.5, 3.8) |

| High rate of experienced sexual discrimination | Experiencing sexual discrimination | 1.0 (0.2, 5.5) |

| Accepted PHN | Yes | 0.9 (0.3, 2.6) |

Discussion

In the HPTN 061 Project, the referred sexual partner participants had some notable structural barrier differences in comparison to community-recruited participants. Overall, referred sexual partner participants were significantly poorer, had less education, and were more likely to be unemployed, to have experienced incarceration, and to not have health insurance. Referred sexual partner participants (in comparison to the overall community recruited participants) were also more likely to be older, be HIV infected at enrollment, and less likely to have ever participated in research. No significant differences were observed in sexual risk behaviors or drug use with the exception of reporting younger sexual debut among the referred sexual partner participants as compared to the overall community recruited participants. These findings are congruent with existing literature that also reported few sexual risk behavior differences among comparison groups of MSM [35–37]. Our study extends the scientific understanding by demonstrating that within the African American MSM population, there are those with socio-economic challenges who may not be reached through traditional recruitment methods. Allowing community-recruited participants to make referrals has been reported to provide the benefit of reaching sectors of populations that may not be accessible through other methods [26, 28].

On the other hand, the referred sexual participants were similar to their community-recruited partners. If a sexual partner referral was HIV positive, under 30 years old, had a STI at enrollment, or was ever incarcerated, the odds were significantly elevated that the community-recruited participant who made the referral also had those same characteristics, similar to finding from studies using respondent-driven sampling [38, 39]. The community-recruited participants who successfully referred sexual partners were also more likely to have attended one or two more Peer Health Navigator meetings as compared to those who did not successfully refer sexual partner participants. Community-recruited participants who attended a PHN meeting may have seen the value in the program and thus more willing make a referral. We do not know what percentage of referrals were made before or after PHN meeting(s) attendance, thus in future studies, assessing the timing of referrals in relationship to participation in an intervention could be beneficial.

A key health-related context that this particular study may have also illustrated is that of “positional inequality” [40], even within the group of at-risk African American MSM. Christakis and Fowler [40] point out inequality occurs because of whom we are connected to and not just based on the demographics that determine our social rankings. In fact, Sari Reisner and colleagues [41] in 2010 suggest that “seed” (or index participants) who are more productive recruiters may have denser social networks and strong social ties. Thus, the community-recruited men who made referrals, while by US society standards were more marginalized than their counterparts who did not make referrals, may have been better connected to those who had structural barriers to care access. In addition, it is plausible that, because of their overall knowledge of risk within their communities and seemingly better knowledge of the benefits of PHN (because they were more likely to attend at least one meeting), the community-recruited participants who made referrals may have been better connected to those who were not accessible through traditional means. Thus, through the referral process of the HPTN 061 study, it appears researchers gained greater access to African America MSM who were at risk (or possibly already infected) with HIV. However, research is needed in understanding factors that may have impeded some indexes to successfully refer sexual partners to the actualization of those partners participation.

The findings from this analysis of HPTN 061 should be considered within the context of key limitations. First, the index participants were given a narrow basic characteristics list of who they could and could not refer. While this approach kept the focus of the entire project on African American MSM, it is not clear if many of the men did not refer partners because their partners were not African American MSM. The various sites and their community-recruited participants were instructed to refer sexual partner participants but it is not clear that all index participants followed this rule and many may have recruited social (not sexual) “friends”. This information was not collected so it is unknown which referrals were sexual partners and which were social friends. Some indexes as well as referred sexual partners may have chosen to refer or participate because of limited resources (thereby being enticed by the incentives offered) or they may have had the time to participate. Reisner et al. found those of lower socioeconomic status and/or those who regularly used drugs were more productive “seeds” (or indexes) in part because they were “more motivated by…monetary incentives offered [41]”. Such realities of experiencing may have skewed who referred and who of those invited ultimately participated. While all indexes were encouraged to refer sexual partners, only a small proportion was successful in doing so. We were unable to track whether more community-recruited participants attempted to refer sexual partners who may not have enrolled. Another limitation was that the sample sizes of the comparison groups of the overall referred sexual partner participants (as compared to the overall community-recruited) and the indexes that successfully referred (as compared to those who did not) were small. Thus, the confidence intervals were wide for the comparisons.

There is diversity even within marginalized groups such as African American MSM that necessitate innovative ways to recruit those harder to engage both in research as well as care and treatment. Our findings like other existing evidence show that referrals made by community-recruited participants are a viable technique to engage those who are difficult to reach by other recruitment strategies. However, additional research questions are raised because of this analysis. Did more eligible community-recruited indexes actually reach out to sexual partners who just did not come in? Or were some community-recruited partners less likely to recruit their sexual partners, or did their partners not meet the project enrollment criteria? How would the distributions across the factors differ if more men were successful in recruiting sexual partners? Why were the composite scores of perceived discrimination (based on racism and sexual orientation) so low for the referred sexual partner participants? And ultimately, was the project successful in capturing the widest array of the African American MSM across the country who are at-risk for HIV or were there some that were still just not reached? Future HIV intervention programs aimed at African American MSM should encourage sexual partner referrals. In evaluating such programs, future efforts should assess if positive intervention involvement, with peers, is a critical tipping point for participants to recruit others who may be hard-to-reach within the community.

Acknowledgments

HPTN 061 grant support was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Cooperative Agreements UM1 AI068619, UM1 AI068617, and UM1 AI068613. Additional site funding was provided by the Fenway Institute CRS: Harvard University CFAR (P30 AI060354) and CTU for HIV Prevention and Microbicide Research (UM1 AI069480). Further support came from the George Washington University CRS: District of Columbia Developmental CFAR (P30 AI087714); Harlem Prevention Center CRS and NY Blood Center/Union Square CRS: Columbia University CTU (5U01 AI069466) and ARRA funding (3U01 AI069466-03S1). This project received support from the Hope Clinic of the Emory Vaccine Center CRS and The Ponce de Leon Center CRS: Emory University HIV/AIDS CTU (5U01 AI069418), CFAR (P30 AI050409) and CTSA (UL1 RR025008). Finally, this paper was also supported by the San Francisco Vaccine and Prevention CRS: ARRA funding (3U01 AI069496-03S1, 3U01 AI069496-03S2) in addition to the UCLA Vine Street CRS: UCLA Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases CTU (U01 AI069424). The lead author would also like to recognize the support of her colleagues and leadership at Howard Brown Health Center, Jamal Edwards, Emilio German, and her family.

HPTN 061 grant support provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Cooperative Agreements UM1 AI068619, UM1 AI068617, and UM1 AI068613. Additional site funding—Fenway Institute Clinical Research Site (CRS): Harvard University CFAR (P30 AI060354) and CTU for HIV Prevention and Microbicide Research (UM1 AI069480); George Washington University CRS: District of Columbia Developmental CFAR (P30 AI087714); Harlem Prevention Center CRS and NY Blood Center/Union Square CRS: Columbia University CTU (5U01 AI069466) and ARRA funding (3U01 AI069466-03S1); Hope Clinic of the Emory Vaccine Center CRS and The Ponce de Leon Center CRS: Emory University HIV/AIDS CTU (5U01 AI069418), CFAR (P30 AI050409) and CTSA (UL1 RR025008); San Francisco Vaccine and Prevention CRS: ARRA funding (3U01 AI069496-03S1, 3U01 AI069496-03S2); UCLA Vine Street CRS: UCLA Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases CTU (U01 AI069424).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest No conflicts were declared.

Contributor Information

Grace Hall, Email: glh6@cdc.gov, Howard Brown Health Center, 4025 N. Sheridan Road, Chicago, IL 60613, USA.

Keala Li, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Leo Wilton, Department of Human Development, College of Community and Public Affairs, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY, USA.

Darrell Wheeler, Graduate School of Social Work, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Jessica Fogel, Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Lei Wang, Vaccine and Infectious Disease Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, USA.

Beryl Koblin, Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention, New York Blood Center, New York, NY, USA.

References

- 1.Bradley H, Hall I, Wolitski RJ, et al. Vital Signs: HIV diagnosis, care, and treatment among persons living with HIV—United States 2011. [Accessed Dec 2014];MMWR. 2014 63(47):1113–7. From http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Normand J, Montaner J, Fang CT, Wu Z, Chen YM. HIV: seek, test, treat, and retain. J Food Drug Anal. 2013;21(4):S4–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Sep 2014];HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men. 2012 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/gender/msm/facts/index.html.

- 4.Rosenberg ES, Millett GA, Sullivan PS, del Rio C, Curran JW. Understanding the HIV disparities between blacks and white men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modeling study. Lancet. 2014;1(3):e112–8. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(14)00011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH, et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of black men who have sex with men in the United States. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg ES, Sullivan PS, Kelley CF, et al. [Accessed 15 Mar 2014];Race and age disparities in HIV incidence and prevalence among MSM in Atlanta, GA. 2014 from http://croi2014.org/sites/default/files/uploads/CROI2014_Final_Abstracts.pdf.

- 7.Outlaw AY, Phillips G, Hightow-Weidman LB, et al. Age of MSM sexual debut and risk factors: results from a multisite study of racial/ethnic minority YMSM living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S23–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.9879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millett G, Peterson JL, Flores SA, et al. Comparison of disparities and risk of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9838):411–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Cranston K, et al. Sexual mixing patterns and partner characteristics of black MSM in Massachusetts at increased risk for HIV infection and transmission. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):602–22. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9363-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, et al. HIV among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0476-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussen SA, Stephenson R, del Rio C, et al. HIV testing patterns among black men who have sex with men: a qualitative typology. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray KM, Cohen SM, Hu X, et al. Jurisdiction level differences in HIV diagnosis, retention in care, and viral suppression in the United States. JAIDS. 2014;65(2):129–32. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holtgrave DR, Kim JJ, Adkins C, et al. Unmet HIV service needs among Black men who have sex with men in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):36–40. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0574-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Millett GA, Jeffries WL, Peterson JL, et al. Common roots: a contextual review of HIV epidemics in black men who have sex with men across the African diaspora. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):411–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60722-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 21 June 2014];HIV among African Americans. from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/racialethnic/bmsm/facts/index.html.

- 17.Brown RE, Ojeda VD, Wyn R, Levan R. [Accessed 6 Aug 2012];Racial and ethnic disparities in access to health insurance and health care. 2000 From http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4sf0p1st#page-4.

- 18.Sullivan PS, Carballo-Dieguez A, Coates T, et al. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melendez RM, Pinto RM. HIV prevention and primary care for transgender women in a community-based clinic. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(5):387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogart LM, Thorburn S. Are HIV/AIDS conspiracy beliefs a barrier to HIV prevention among African Americans? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(2):213–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200502010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fields EL, Bogart LM, Galvan FH, et al. Association of discrimination-related trauma with sexual risk among HIV-positive African American men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):875–80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilley BJ, Keesee M. Linking ‘White oppression’ and HIV/AIDS in American Indian etiology: conspiracy beliefs among MSMs and their peers. Am Indian Alsk Nativ Ment Health Res. 2007;14(1):44–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond HF, McFarland W. Racial mixing and HIV risk among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(4):630–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9574-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown D, McCree DH, Eke A. Chapter 28: African Americans and HIV: epidemiology, context, behavioral interventions and future directions. In: Hall BJ, Hall JC, Cockerell CJ, editors. AIDS the first 30 years: where we have been, where we are and where we are going. Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei C, McFarland W, Colfax GN, et al. Reaching black men who have sex with men: a comparison between respondent-driven sampling and time-location sampling. Sex Trans Infect. 2012;88(8):622–6. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He H, Wang M, Zaller N, et al. Prevalence of syphilis and associations with sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25(6):410–9. doi: 10.1177/0956462413512804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadland SE, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Feng C, Montaner JS, Evan W. Prescription opioid injection and risk of hepatitis C in relation to traditional drugs of misuse in a prospective cohort of street youth. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel A, Gauld R, Norris P, Rades T. “This body does not want free medicines”: South African consumer perceptions of drug quality. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(1):61–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faugier J, Sargeant M. Sampling hard to reach populations. J Adv Nurs. 1997;26(4):790–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease ControlPrevention. HIV prevalence, unrecognized infections and HIV testing among men who have sex with men-Five U.S. cities. MMWR. 2005;54:597–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mayer KH, Wang L, Koblin BA, et al. Concomitant socioeconomic, behavioral, and biological factors associated with the disproportionate HIV infection burden among black men who have sex with men in 6 U.S. cities. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e87298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Barbor TF, de la Fuentes JR, Grant M. Development of the alcohol use disorders identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption–II. Addictions. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herek GM. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: correlates and gender differences. J Sex Res. 1988;25(4): 451–77. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrell SP, Merchant MA, Young SA. Psychometrics properties of the racism and life experiences scales (RaLES) Chicago Il: American Psychological Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Denning PH, Campsmith ML. Unprotected anal intercourse among HIV positive men who have steady male partners with HIV negative or unknown status. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(1):153–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.017814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malebranche DJ. Black men who have sex with men and the HIV epidemic: next steps for public health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):862–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Valleroy LA, MacKellear DA, Karon JM, et al. HIV prevalence and associated risk in young men who have sex with men. JAMA. 2000;284(2):198–204. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, et al. Using respondent-driven sampling methodology for HIV biological and behavioral surveillance in international settings: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(4 Suppl):S105–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wylie JL, Jolly AM. Understanding recruitment: outcomes associated with alternative methods for seed selection in respondent driven sampling. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christakis NA, Fowler JH. Connected: The surprising power of our social networks and how they shape our lives-how your friends ‘friends’ affect everything you feel, think, and do. New York: Back Bay Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Johnson CV, et al. What makes a respondent-driven sampling “seed” productive? Example of finding at-risk Massachusetts men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):467–79. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9439-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]