Abstract

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) are frequent, commonly recurrent, and costly. Deficiency in a key autophagy protein, ATG16L1, protects mice from infection with the predominant bacterial cause of UTIs, Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC). Here, we report that loss of ATG16L1 in macrophages accounts for this protective phenotype. Compared to wild-type macrophages, macrophages deficient in ATG16L1 exhibit increased uptake of UPEC and enhanced secretion of IL-1β. The increased IL-1β production is dependent upon activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1. IL-1β secretion was also enhanced during UPEC infection of ATG16L1 deficient mice in vivo, and inhibition of IL-1β signaling abrogates the ATG16L1-dependent protection from UTIs. Our results argue that ATG16L1 normally suppresses a host-protective IL-1β response to UPEC by macrophages.

Keywords: autophagy, urinary tract infections, inflammasome, lysosome, caspase-1, NLRP3, bladder

INTRODUCTION

Half of all women will suffer from a urinary tract infection (UTI) at some point in their lives. Moreover, in the US, UTIs account for 8 million visits to emergency departments and clinics every year and 15% of all outpatient antibiotic prescriptions1. Despite effective clearance of the acute infection, as many as 10% of those who suffer from a UTI will go on to have recurrent infections that cannot be cured with antibiotics2. Thus, development of effective therapeutics will require an understanding of the ways in which bacteria infect the urinary tract and the defense mechanisms used by the host to combat the infection.

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is the causative agent in 75% of all UTIs2. Mouse models of UTI have revealed that clearance of UPEC from the bladder mucosa depends on the early recruitment of innate immune cells3,4. On the other hand, UPEC have evolved several mechanisms to actively subvert recruitment and response of host immune cells5,6. For example, UPEC suppress production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-67 and attenuate the ability of neutrophils to migrate towards the sites of infection8. However, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the recruitment and functionality of innate immune cells, especially those of the monocyte/macrophages lineage, in response to UPEC infection remains unclear.

Host mucosal defense against pathogens requires coordination of multiple signaling pathways within innate immune cells. One such pathway is autophagy, a cellular recycling pathway responsible for lysosomal degradation of cytosolic components, including damaged organelles, protein aggregates and intracellular pathogens9,10. The autophagy pathway in general, and the autophagy gene/protein ATG16L1 in particular, plays an important role in innate immune responses to infection11. A common polymorphism in ATG16L1 (T300A) remains prevalent within the Caucasian population and is associated with Crohn's disease12,13, a form of inflammatory bowel disease. An open question remains as how this ‘bad’ risk allele is prevalent in the population.

Recent studies have revealed that autophagy and ATG16L1 can dampen activation of the innate immune response to infection as well as activation of inflammasomes10,11, key signaling complexes that detect pathogenic microorganisms and which in turn activate the highly pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β)14. In particular, ATG16L1 and autophagy have been suggested to play a role in the production of IL-1β15,16 as well as another pro inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα)17,18. However, the mechanisms by which autophagy and ATG16L1 regulates the inflammasome in the context of infection are still uncertain.

We recently showed that mice deficient in ATG16L1 (Atg16L1HM 19,20, carrying a hypomorphic allele that reduces Atg16l1 expression) cleared UPEC infection more rapidly and thoroughly than controls21. We further demonstrated that ATG16L1 deficiency in the hematopoietic compartment was the primary driver of increased clearance of UPEC, although the adaptive immune compartment did not contribute to the protective phenotype21. These findings argue that loss of ATG16L1 in the innate immune system is responsible for resistance to UTIs, yet the underlying mechanism for this resistance remains to be examined.

In this report, we demonstrate that macrophages are essential for the control and clearance of UPEC from the bladders of ATG16L1-deficient mice. Mechanistic studies using primary macrophages revealed that loss of ATG16L1 increases bacterial uptake and enhances release of the cytokine IL-1β, but not TNFα, in response to UPEC. The increased IL-1β production is independent of NOD2 or gross lysosomal damage, but is dependent on caspase-1 and the NLRP3 inflammasome. Finally, we show that augmented IL-1β signaling is the primary mechanism responsible for enhanced clearance of UPEC from the urinary tract in ATG16L1-deficient mice. Together, our findings show that ATG16L1 deficiency makes macrophages better able to control UPEC infection in vivo during a UTI by regulating levels of IL-1β. Our findings have implications for elucidating how UPEC is able to evade host innate defenses to cause a UTI and suggest that polymorphisms in ATG16L1 may be maintained in the population because of protective effects from a common infection.

RESULTS

Macrophages are required for UPEC clearance in Atg16L1HM mice

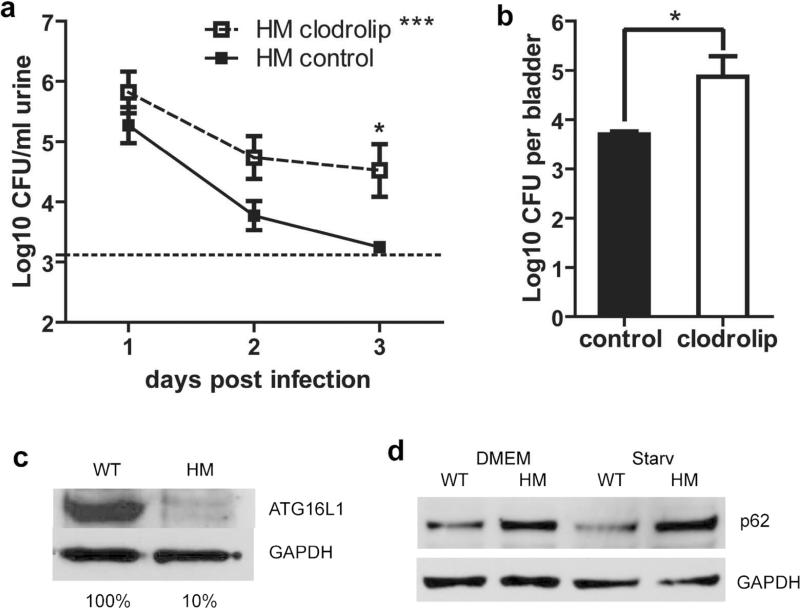

We previously found that monocyte recruitment was enhanced in the bladders of infected ATG16L1-deficient (Atg16L1HM) mice compared to those of infected wild-type (WT) animals21. Furthermore, Atg16L1HM mice cleared their UTIs more rapidly than WT mice. To determine whether monocytes and macrophages were necessary for this effect, we depleted monocytes and macrophages from Atg16L1HM mice by treating them with clodronate-containing liposomes (clodrolip)22,23 followed by transurethral infection with a well-characterized clinical cystitis strain of UPEC (UTI89). Clodrolip treatment decreased the number of systemic macrophages and monocytes in the spleens of Atg16L1HM mice by greater than 60% (Supplementary Figure 1), reduced the recruitment and number of macrophages in the bladder mucosa after infection (Supplementary Figure 2) and significantly attenuated their enhanced ability to clear the infection (Figure 1a and b). Furthermore, clodrolip treatment resulted in higher urine and bladder titers at three days post infection in Atg16L1HM mice relative to WT mice(Figure 1a-b). Clodrolip treatment can also deplete CD11c+ dendritic cells, however, it has been previously shown that dendritic cells are dispensable for UPEC pathogenesis24. Thus, we argue that macrophages or monocytes are essential for enhanced clearance of UTI89 in Atg16L1HM mice.

Figure 1. Macrophages and monocytes are essential for bacterial control in Atg16L1HM mice.

(a-b) CFU counts of bacteriuria (a) or 3dpi bladder homogenates (b) from Atg16L1HM mice treated with clodrolip or control liposomes as displayed as mean Log10CFU/ml and SEM. For a, n=3 independent experiments, for a total of 12 clodrolip treated mice and 13 control liposome treated mice. For b, n=2 independent experiments, for a total of 9 clodrolip treated mice and 9 control liposome treated mice. Two-way ANOVA with matching by animal, ***P<0.001, with bonferroni post-test at individual time points (a), and unpaired T-test (b), * P<0.05. (c) ATG16L1 levels in BMDMs from WT and Atg16L1HM mice as measured by western blot. (d) Western blot of p62 in samples of WT and ATG16L1-deficient BMDMs. Starvation (Starv) was used to induce autophagy. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, used as a loading control in (c) and (d). Data is representative of 3 independent experiments (c and d).

Altered UTI89 uptake and processing by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages

Macrophages have direct bactericidal functions and also secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines to orchestrate the host response to pathogens. Given the evidence that ATG16L1 deficiency in macrophages was crucial for the observed enhanced clearing of UTI89 in vivo, we sought to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying how ATG16L1 deficiency altered the response of macrophages to UTI89. To address this question, we isolated bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) from WT and Atg16L1HM mice and challenged them with UTI89. As expected, BMDMs from Atg16L1HM mice displayed a 90% reduction of ATG16L1 protein (Figure 1c). Consistent with a reduced rate of autophagic flux, they also accumulated the adaptor protein p62 (Figure 1d).

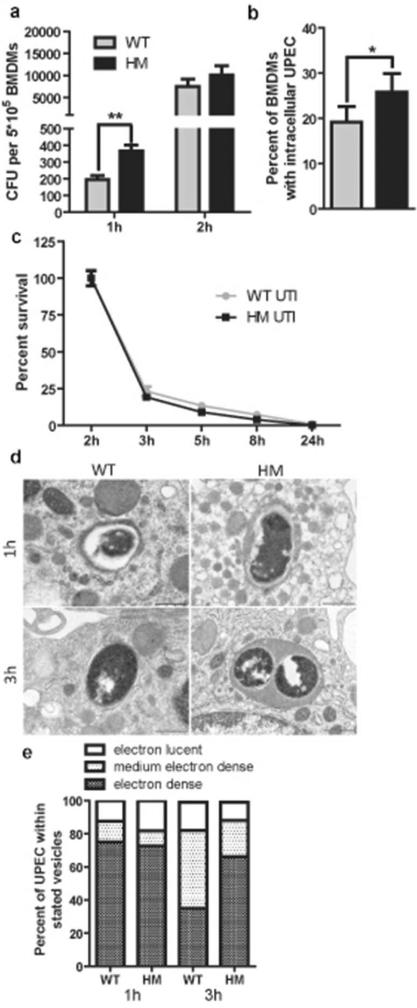

To assess the direct effect of ATG16L1 deficiency on bacterial clearance, we determined intracellular bacterial load at multiple time points post-infection and found that Atg16L1HM BMDMs contained significantly more bacteria than WT BMDMs at 1 hour post-infection (hpi) (Figure 2a). Likewise, immunofluorescence (IF) staining showed that more Atg16L1HM BMDMs contained intracellular bacteria than WT macrophages (Figure 2b, Supplementary Figure 3a). To determine whether ATG16L1 deficiency affects degradation of intracellular bacteria, we quantified the intracellular bacterial load in BMDMs over time as compared to levels at 2 hpi. We observed a similar pattern of decrease in bacterial counts between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages, arguing that the dynamics of bacterial killing over time was not altered by ATG16L1 deficiency (Figure 2c). Together, these findings indicate that ATG16L1 deficiency enhances killing of UTI89 by increasing bacterial uptake at early stages of infection. To examine whether ATG16L1 deficiency affected intracellular trafficking of UTI89, we performed IF and observed co-localization of UPEC with the lysosomal marker LAMP1 in both WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Supplementary Figure 3b). To further evaluate the intracellular localization of UTI89 within macrophages, we used transmission electron microscopy (TEM). At 1 and 3 hpi, consistent with the IF results, UTI89 were consistently found in single-membrane compartments in both WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Figure 2d). We counted the numbers of bacteria in electron-lucent or highly electron-dense compartments. At 1 hpi, the majority of bacteria appeared to be in highly electron-dense lysosomal compartments in both WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Figure 2e). However, by 3 hpi, whereas fewer bacteria were within highly electron-dense compartments in WT macrophages, the majority of bacteria still remained in these compartments in ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Figure 2e). This suggests that UTI89 alters its phagocytic compartment in macrophages over time but does so more slowly in ATG16L1-deficient cells. Thus, ATG16L1-deficient macrophages may sense and respond to intracellular UTI89 differently than WT macrophages do.

Figure 2. ATG16L1-deficient macrophages take up more bacteria than WT macrophages.

(a) Intracellular bacterial load of WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages at different times after UTI89 challenge. (b) Percent of macrophages that contained intracellular bacteria by immunoflourescence. (c) Intracellular bacterial survival displayed as percentage of intracellular CFU load at 2 hr. (d) TEM images of UTI89 within single-membrane vacuoles of different electron density at different time points (Scale bars = 500 nm), and (e) quantification of the distribution of vacuole types within which UPEC was found in WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages. **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Paired t-test (b) or two-way ANOVA with bonferroni post tests (a and c). Data are from 3 independent experiments, with 3 replicates per experiment (a and c) or 4 fields per experiment (b) presented as mean and SEM.

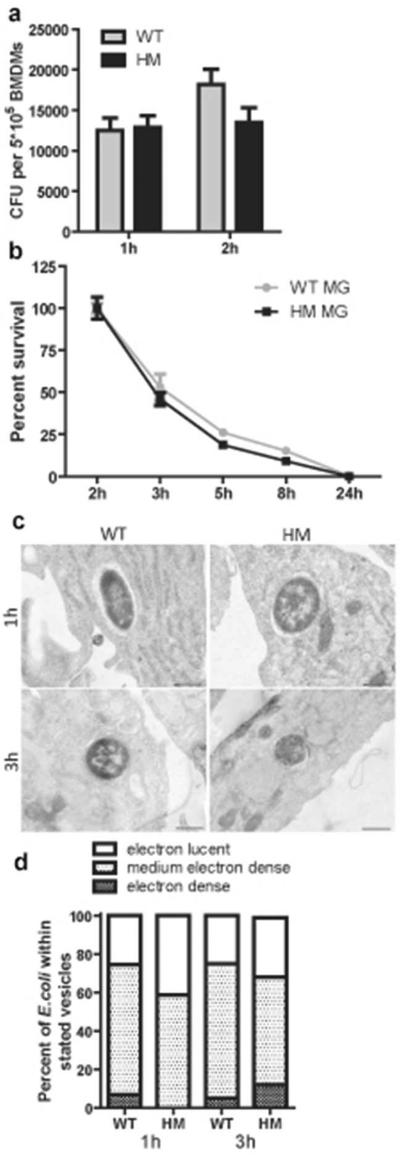

To determine whether the increased uptake by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages was specific to a UPEC strain or would be elicited by any intracellular E. coli, we challenged the macrophages with a commensal E. coli (MG1655)25. At 1 hpi, macrophages of both genotypes took up the commensal bacteria more efficiently than UTI89 (compare Figure 3a to Figure 2a). However, no significant differences in uptake (Figure 3a) or survival rates of MG1655 (Figure 3b) were observed between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages. TEM analysis revealed that, at 1 and 3 hpi, MG1655 were in single-membrane compartments, the majority of which were not highly electron-dense (Figure 3c). Moreover, the distribution of types of compartments containing MG1655 did not differ between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Figure 3d). We conclude that loss of ATG16L1 affects intracellular trafficking of UTI89 but not of a commensal strain of E. coli.

Figure 3. ATG16L1-deficient macrophages take up MG1655, an avirulent E. coli strain differently than the UPEC strain.

(a) Intracellular bacterial load of WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages at 1 and 2 hours after MG1655 challenge. (b) Intracellular bacterial survival displayed as percentage of intracellular CFU load at 2 hours. (c) TEM images of MG1655 within single-membrane vesicles of different electron density at different time points, and (d) quantification of the distribution of vesicle types within which MG1655 was found in WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages. Not significant by two-way ANOVA with bonferroni post-tests (a and b). Data are from 3 independent experiments, with 3 replicates per experiment (a and b) presented as mean and SEM.

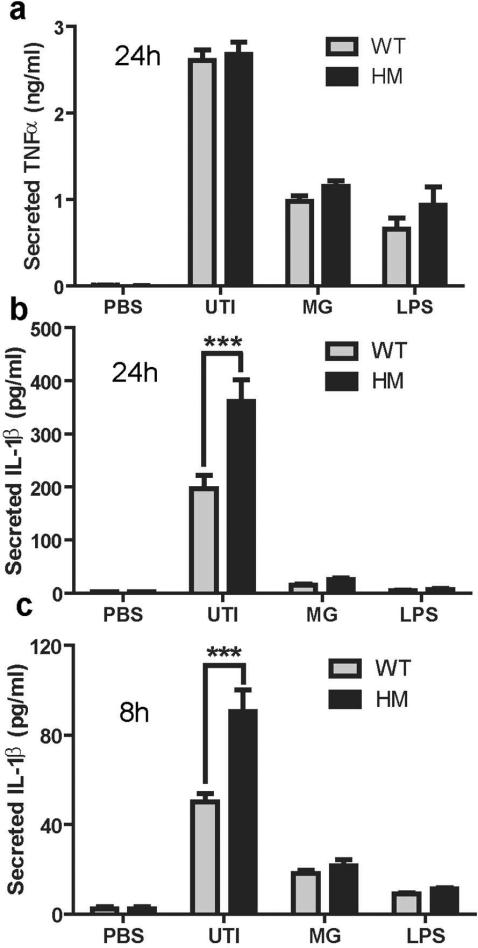

ATG16L1-deficient macrophages secrete more IL-1β in response to UPEC challenge

Given the important link between autophagy and inflammation, we reasoned that the cytokine response elicited by UTI89 may be altered in macrophages deficient in ATG16L1. To test this hypothesis, we challenged WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages with UTI89, MG1655, or LPS. In response to these stimuli, WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages secreted similar amounts of TNFα at 24 hpi (Figure 4a). In contrast, IL-1β release was significantly higher in UPEC-infected ATG16L1-deficient macrophages compared to control macrophages at 24 hpi (Figure 4b) and this response could be detected as early as 8 hpi (Figure 4c). No IL-1β was detected in WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages at 2hpi suggesting that increased IL-1β did not directly enhance UPEC uptake (Supplementary Figure 4a). Interestingly, IL-1β release only occurred following infection with the UPEC strains (UTI89 and CFT07326, a pyelonephritis strain, Supplementary Figure 4b), not in response to commensal E. coli or LPS (Figure 4b and c). Further, dose-dependent increases in IL-1β production was observed in WT macrophages treated with varying concentrations of 3-MA, an autophagy inhibitor that targets VPS34, suggesting that the increased IL-1β production by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages in response to UTI89 may be the result of their autophagy deficiency (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 4. ATG16L1-deficient macrophages produce more IL-1β than WT macrophages.

Levels of (a) TNFα and (b) IL-1β in the supernatants of WT and ATG16L1-deficient cells 24 hours after challenge with UTI89, MG1655, or LPS. (c) Levels of IL-1β in the supernatant after 8 hours of challenge with UTI89, MG1655 or LPS as determined by ELISA. ***P<0.001. Two-way ANOVA with bonferroni post-tests. Data are from three (a and c) and four (b) independent experiments presented as mean and SEM.

Increased IL-1β production by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages is independent of NOD2 activity and enhanced transcription of pro-IL-1β

IL-1β release is tightly controlled through the combination of two distinct triggers. First, activation of Toll-like receptor (TLRs) or Nod-like receptors (NLRs), such as by LPS, induces transcription of pro-IL-1β27,28. In a second step, pro-IL-1β protein is cleaved by caspase-1, a process that is regulated by inflammasomes, which are defined by their NLR component, which can include AIM2, NLRC4, NLRP1, and NLRP328. Thus, we wanted to know whether ATG16L1 deficiency affected pro-IL-1β generation (signal 1) or assembly of the inflammasome complex (signal 2).

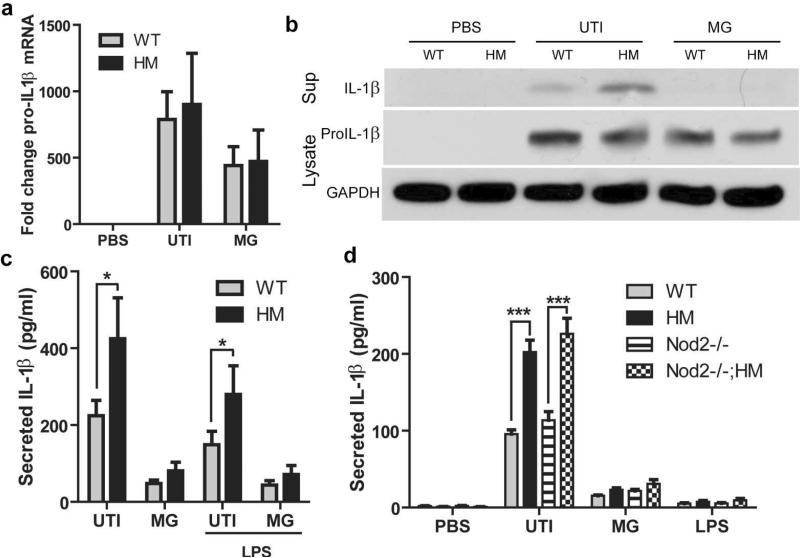

No significant differences were observed in level of pro-IL-1β mRNA (Figure 5a) or protein (Figure 5b) between ATG16L1-deficient and WT macrophages challenged with UTI89, even though increased cleaved IL-1β was observed in the supernatants by western blot. Additionally, caspase-11 and NLRP3 protein levels increased upon infection, but there was no significant difference between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Supplementary Figure 6). Furthermore, when we pre-treated cells with LPS to activate transcription of pro-IL-1β before activation by UTI89 ATG16L1-deficient macrophages still produced more IL-1β in response to UTI89 than WT cells did (Figure 5c). These findings argue enhanced IL-1β release in ATG16L1-deficient macrophages does not occur via modulation of signal 1.

Figure 5. Increased IL-1β secretion by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages is not due to enhanced signal 1 or NOD2.

(a) Levels of pro-IL-1β mRNA determined by quantitative PCR from macrophages at baseline or after 3 hours of challenge with UTI89 or MG1655. (b) Representative western blot of cleaved IL-1β in the supernatant at 24 hours and pro-IL-1β and GAPDH levels at 3 hours from macrophages treated with PBS or challenged with UTI89 or MG1655. (c) IL-1β level in the 24 hour supernatant of BMDMs pretreated with LPS or PBS for 4 hours before challenge with UTI89 or MG1655. (d) Levels of IL-1β in the supernatants of BMDMs from WT, ATG16L1HM, Nod2−/−, and Nod2−/− ; Atg16L1HM mice 24 hours after challenge with UTI89. ***P<0.001. Paired t-test (c) or two-way ANOVA with bonferroni post-tests (a and d). Data are from two (c) or three (a and d) independent experiments with three replicates per experiment presented as mean and SEM.

Recent studies have suggested that ATG16L1 is important for controlling secretion of IL-1β and TNFα in response to agonists of NOD2, an NLR that recognizes cytosolic bacterial components17,29,30. We thus asked whether NOD2 was required for the increased IL-1β secretion of UTI89-challenged ATG16L1-deficient macrophages. We found that macrophages from Nod2−/− and WT mice produced equivalent levels of IL-1β (Figure 5d). Likewise, upon challenge with UTI89, macrophages from Nod2−/−; Atg16L1HM mice produced similar amounts of IL-1β as macrophages from Atg16L1HM mice (Figure 5d), suggesting that NOD2 does not contribute to ATG16L1-deficiency-mediated increased secretion of IL-1β upon UPEC infection.

UTI89 activates NLRP3 inflammasomes in macrophages

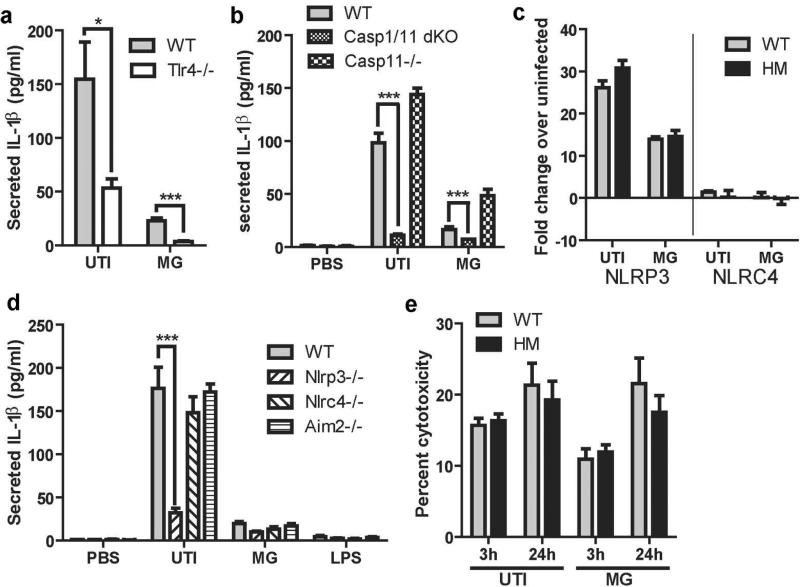

As our findings suggested that ATG16L1 deficiency likely impacts signal 2, we sought to define that mechanism by which UTI89 activates the inflammasome. Importantly, inflammasome activation in macrophages in response to UPEC had not been previously examined. Thus, we first confirmed that UTI89-induced IL-1β production was dependent on TLR4 activation; as expected, BMDMs from TLR4−/− mice produced significantly decreased levels of IL-1β (Figure 6a). Next, we determined if both caspase-1 and caspase-11 were essential for IL-1β secretion in response to UTI89. BMDMs isolated from caspase-1/caspase-11 double knockouts had minimal secretion of IL-1β in response to UTI89 and MG1655, but caspase-11 deficient mice had no defect in IL-1β secretion in response to UTI89 (Figure 6b). This suggests that UTI89 activates the canonical inflammasome rather than the non-canonical caspase-11 activated inflammasome31. To further define the key inflammasome proteins activated upon UPEC challenge, we performed q-RTPCR analysis of genes encoding two inflammasome proteins that sense and respond to bacteria (NLRC4 and NLRP3) 27,32,33 and found that whereas Nlrc4 transcription was minimally induced, Nlrp3 transcription was highly upregulated in response to UTI89 infection of both WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages (Figure 6c). We then examined IL-1β production by macrophages from mice lacking the inflammasome proteins NLRP3, NLRC4, or AIM2. Macrophages from Nlrp3−/− mice secreted significantly less IL-1β than WT macrophages (Figure 6d). In contrast, macrophages from Nlrc4−/− and Aim2−/− mice produced roughly the same amount of IL-1β as WT macrophages. Together, these findings demonstrate that most IL-1β secretion in response to UTI89 requires TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Figure 6. TLR4 and NLRP3 activation by UPEC are important for IL-1β production.

(a) Amount of IL-1β secreted by WT and Tlr4−/− macrophages in response to UTI89 and MG1655. (b) Amount of IL-1β secreted by WT, caspase1/11 double knockouts, or caspse11−/− macrophages in response to UTI89 and MG1655. (c) Levels of Nlrp3 and Nlrc4 mRNA (determined by quantitative PCR) in macrophages after challenge with UTI89 or MG1655 for 3 hours, presented relative to the 0 hour timepoint. (d) Secreted IL-1β detected by ELISA from macrophages from WT, Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4−/−, and Aim2−/− mice in response to UTI89, MG1655, and LPS challenge. (e) Measurement of cytotoxicity as LDH release by BMDM exposed to UTI89 for 3 hours or 24 hours (2 hours exposure to extracellular bacteria followed by incubation for 22 hours in gentamicin) as a percentage of total LDH release upon tritonX treatment. * P <0.05, *** P <0.001. Two way ANOVA and bonferroni post-test for each pair. Data are from 2 (a, b, and d) or 3 (c and e) independent experiments with 3 individual replicates per experiment.

In response to infection, macrophages can kill intracellular pathogens by undergoing a form of cell death called pyroptosis, which is associated with IL-1β release and caspase-1 activation34. It is not known if UPEC induce pyroptosis in macrophages. Thus, we investigated the effect of ATG16L1 deficiency on pyroptosis in response to UTI89 infection by using the CytoTox 96 assay, which measures the levels of release of the cytoplasmic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase into the supernatant. We detected no difference in total cell death between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages challenged with UTI89 or MG1655 (Figure 6e), suggesting that pyroptosis is not a mechanism of fast clearance of UTI89 in Atg16L1HM mice.

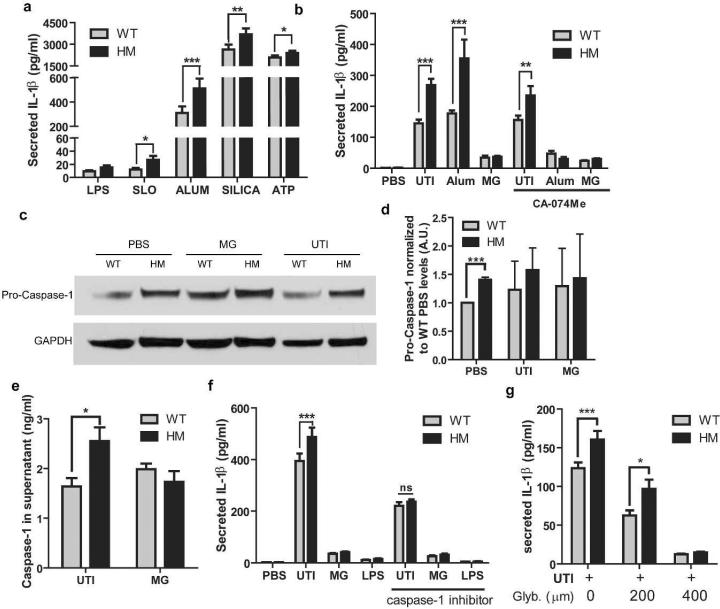

ATG16L1 deficiency enhances IL-1β secretion in response to UTI89 and other NLRP3 activators due to increased caspase-1 activation

Given that pro-IL-1β levels were similar between WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages, we hypothesized that the increased IL-1β secretion by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages was due to increased activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1. To determine whether ATG16L1 deficiency enhanced NLRP3 activation, we treated WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages with four known NLRP3 activators: Streptolysin-O, ATP, Alum, and Silica35,36. Each caused secretion of IL-1β by both types of macrophages, but in each case, ATG16L1-deficient macrophages produced more IL-1β than WT macrophages did (Figure 7a). Given that lysosome damage can trigger NLRP3 activation,28,37,38 in conjunction with our data indicating that UPEC traffics to lysosomes in macrophages, we reasoned that UPEC might activate the NLRP3 inflammasome by impairing lysosome integrity and inducing release of cathepsin B and other vacuolar contents into the cytosol. To test this, we treated UTI89 infected WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages with the cathepsin B inhibitor CAO74-ME 38. As expected, CAO74-ME decreased the secretion of IL-1β in response to Alum, a known inducer of lysosome damage36. In contrast, the release of IL-1β in response to UPEC was unaffected by cathepsin B inhibition (Figure 7b). Thus, inflammasome activation by UTI89 occurs without major lysosomal injury and cathepsin B release. This is consistent with our TEM observation that UTI89 were found within intact vacuoles in both WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages. These findings suggest that activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome occurs independently of gross lysosomal damage by UTI89.

Figure 7. ATG16L1-deficient macrophages produce more IL-1β due to increased NLRP3 and caspase-1 activity.

(a) Levels of IL-1β in the supernatants of WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages after pretreatment with LPS followed by exposure to Streptolysin O (with 10 mM DTT), Alum, Silica, or ATP. (b) Levels of IL-1β in the supernatants of WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages challenged with UTI89 for 24 hours or the NLRP3 activator Alum for 8 hours with or without the Cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074Me. (c) Representative western blot of pro-caspase-1 protein levels normalized to GAPDH values from macrophages at baseline and after 3 hours of UTI89 challenge, quantification (d) displayed normalized to baseline WT levels. A.U., arbitrary units. (e) Level of caspase-1 in the supernatants of macrophages challenged with UTI89 for 24 hours. (f) Level of IL-1β in the supernatants of macrophages challenged with UTI89 for 24 hours with or without a caspase-1 inhibitor during the entire experiment. (g) Level of IL-1β in the supernatants of macrophages challenged with UTI89 for 24 hours with increasing concentrations of glyburide, an NLRP3 inhibitor. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Paired t test (a) or two way ANOVA and bonferroni post test at for each condition (b, d-g). Data are from 3 independent experiments with 3 replicates per experiment (a-b, e-g) or 1 replicate per experiment (d) presented as mean with SEM.

We then determined the effect of ATG16L1 deficiency on caspase-1 activation. The levels of pro-caspase-1 in uninfected ATG16L1-deficient macrophages were higher than those observed in WT macrophages (Figure 7c and d). Upon challenge with UPEC, ATG16L1-deficient macrophages released more caspase-1 into the supernatant than WT macrophages, consistent with enhanced activation of this protease (Figure 7e and Supplementary Figure 6). To determine whether the difference observed in IL-1β secretion by WT and ATG16L1-deficient macrophages was due to changes in caspase-1 activity, we applied a caspase-1 inhibitor during infection. Caspase-1 inhibition, using 10μM Z-WEHD-FMK, eliminated the difference in secretion of IL-1β between WT and ATG16L1-deficient BMDMs (Figure 7f). Additionally, inhibiting NRLP3 with glyburide was able to inhibit IL-1β production in both WT and ATG16L1-deficient BMDMs in a dose dependent manner (Figure 7g). We conclude that NLRP3 and caspase-1 activation is enhanced by ATG16L1 deficiency, and this pathway mediates the enhanced release of IL-1β by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages in response to UTI89 challenge.

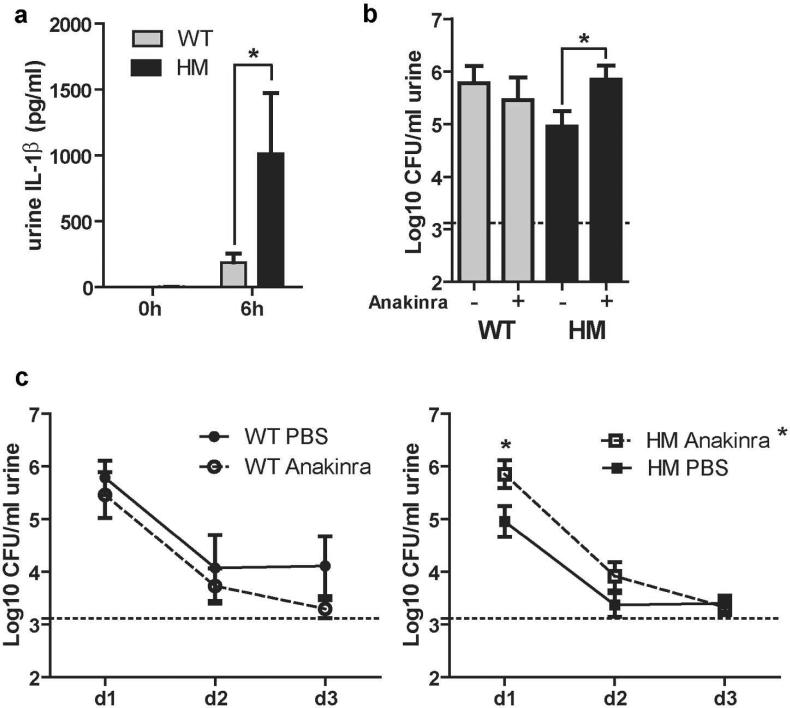

Blocking IL-1 signaling in Atg16L1HM mice reduces clearance of UPEC during a UTI

Our data suggest that Atg16L1HM mice are better able to clear a UPEC infection than WT mice for two reasons. First, as previously shown, more macrophages are recruited to the bladder mucosa21. Second, ATG16L1-deficient macrophages produce more IL-1β ex vivo in response to UPEC challenge due to increased caspase-1 activation (Figure 4b). In agreement with our mechanistic ex vivo studies, we found significantly more IL-1β in urines from Atg16L1HM mice than in urines from WT mice at 6 hpi (Figure 8a). To determine the physiological importance of IL-1β in vivo, we treated both WT and Atg16L1HM mice with Anakinra (a recombinant form of the endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-1Ra, which blocks both IL-1α and IL-1β signaling through IL-1R) to inhibit IL-1 signaling during infection39. Anakinra reduced bacterial clearance in Atg16L1HM mice compared to vehicle treated controls at 1dpi, whereas bacteriuric titers were not significantly affected in WT mice given vehicle (PBS) or Anakinra at 1dpi (Figure 8b). In fact, the infection phenotype of Anakinra-treated Atg16L1HM mice was similar to WT animals. In addition, Anakinra treated Atg16L1HM mice had a significantly worse course of infection than vehicle-treated Atg16L1HM mice (Figure 8c, right), whereas Anakinra treatment did not significantly change the course of infection in WT animals (Figure 8c, left). Thus, our data argue that in the context of WT macrophages, subverting IL-1β production is not a part of the UPEC arsenal of host defense evasion. However, our results demonstrate that the augmented IL-1β release from macrophages in Atg16L1HM mice is the primary driver of enhanced bacterial clearance in those mice.

Figure 8. IL-1β production is enhanced in Atg16L1HM mice and is important for faster clearance of UPEC.

(a) Urine levels of IL-1β at baseline and 6 hpi as measured by ELISA (b) CFU counts of day one bacteriuria from WT and Atg16L1HM mice given IP PBS or Anakinra. (c) Bacteriuria over time from WT (left) or Atg16L1HM (right) mice treated with Anakinra or PBS displayed as mean Log10CFU/ml. *P<0.05, Two-way ANOVA with matching by animal and bonferroni post-test at each time point (a and c) and Mann Whitney test (b). Data are from (a) two independent experiments with a total of 7 WT and 6 Atg16L1HM mice examined, and from (b-c) four independent experiments with 13 PBS treated Atg16L1HM mice, 11 Anakinra treated Atg16L1HM mice, 8 PBS treated WT mice, and 7 Anakinra treated WT mice, all are presented as mean with SEM.

DISCUSSION

Autophagy and its proteins are important for combating intracellular pathogens and have generally been considered to be anti-pathogenic11. However, emerging evidence suggests that autophagy proteins can also be pro-pathogenic21,40,41. In previous work, we found that ATG16L1-deficient mice display reduced levels of bacteriuria and bladder titers early in infection21. Our work suggested that hematopoeitic cells were important for ATG16L1-deficiency-mediated protection, but did not reveal the mechanism by which this occurred.

In this report, we showed that ATG16L1 deficiency-mediated protection from UTIs is dependent on the macrophage/monocyte lineage in vivo. ATG16L1 deficiency in the macrophage/monocyte lineage promoted a more robust IL-1β response to UPEC challenge, and blockade of IL-1 signaling in vivo abolished the protective phenotype mediated by ATG16L1 deficiency. Additionally, our findings show for the first time that the NLRP3 inflammasome is the principal inflammasome activated by UPEC during a UTI, with minimal IL-1β production as a result of activation of other inflammasomes including, NLRC4 or AIM2. Furthermore, our work has revealed that the IL-1β response mediated by NLRP3 was dependent on caspase-1 activation. Altogether, our results indicate that loss of ATG16L1 promotes a beneficial innate immune response during a UTI.

UTIs are not the only type of infection in which loss of ATG16L1 can be beneficial. Deficiency of this gene was recently shown to provide significant protection from Citrobacter rodentium infection of the intestine40. Moreover, ATG16L1-deficient macrophages and monocytes were found to be essential for the protection against both infections in these distinct mucosae. However, the underlying mechanisms differ in two ways. First, whereas an ATG16L1-deficient hematopoietic compartment is the main driver for the protective phenotype in UTI21, deficiency in the non-hematopoietic compartment also contributes to reduced Citrobacter titers and increased survival40. Second, although NOD2 plays an essential role in ATG16L1 deficiency-induced resistance to Citrobacter, we found that NOD2 was dispensable for ATG16L1 deficiency-induced resistance to UPEC42 and now show that NOD2 does not affect ATG16L1 deficiency-induced enhanced IL-1β secretion by BMDMs in response to UPEC. These differences suggest that ATG16L1 plays distinct roles in the pathogenesis of different infections.

Nonetheless, these studies indicate that ATG16L1 deficiency may be protective against a broader range of pathogens, particularly those that are not obligate intracellular pathogens and do not thrive within macrophages. For such pathogens, alterations in immune signaling and immune cell recruitment may outweigh any potential defects in controlling intracellular bacteria. Additionally, because UPEC do not thrive within macrophages and are primarily degraded43, we suggest that increased uptake of UPEC or similar pathogens by ATG16L1-deficient macrophages could itself be protective to the host. In contrast, increased uptake of intracellular pathogens that do thrive within macrophages could be detrimental. IL-1β is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a key role in the host response to infection and injury. This cytokine is tightly controlled at the transcriptional and post-translational level by two distinct signals, which prevent inappropriate activation and release44. An additional level of control exists through production of an endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) that competes with IL-1β for binding to the IL-1 receptor. Our work adds to evidence that ATG16L1 and autophagy can modulate the production and release of active IL-1β. Saitoh et al. were the first to show this connection when they discovered that both ATG16L1-deficient fetal liver-derived macrophages and peritoneal macrophages in which basal autophagy was inhibited produced more IL-1β in response to LPS and commensal bacteria but not Salmonella15. Later, Harris et al. showed that autophagy induction promotes the degradation of pro-IL-1β in response to LPS16. Most recently, Lee et al. demonstrated that ATG16L1 regulates IL-1β signaling by controlling p62 levels by autophagosomal and proteosomal degradation45. Our results suggest that increases in IL-1β in response to UPEC in our ATG16L1-deficient macrophages are primarily a result of altered caspase-1 activation rather than up-regulation of transcription as was reported in studies of the T300A variant of ATG16L146. Interestingly, in contrast to what was observed previously15, we found that LPS stimulation of Atg16L1HM macrophages was not sufficient to induce robust IL-1β secretion; this may be related to the degree of ATG16L1 deficiency. Nevertheless, our work provides the first evidence that, instead of harming the host, increased IL-1β secretion due to ATG16L1 deficiency can lead to a more effective response to infection.

The finding that elevated IL-1 signaling was important for the ability of Atg16L1HM mice to control UPEC suggests that ATG16L1 plays a role in dampening the bladder mucosal production of IL-1β in response to UPEC infection. Such dampening may be helpful in preventing excessive inflammation in mucosae that cannot resolve the inflammation. For example, elevated levels of IL-1β due to ATG16L1 deficiency are detrimental in the context of chemically induced colitis15. Inhibition of autophagy in cells infected with Borrelia burgdorferi has been shown to lead to increased IL-1β which is associated with worsened disease progression47. By contrast, increased macrophage-driven inflammation may be helpful in the bladder mucosa48, which is not permeable or absorptive like the gut mucosa and is usually sterile. Thus, the normal balance maintained by ATG16L1 may prevent infections by obligate intracellular pathogens in most cells but may lead to insufficient responses to other pathogens, such as UPEC. Furthermore, the enhanced secretion of IL-1β due to loss of ATG16L1 appears to uncover a vulnerability in the ability of UPEC to evade early innate immune defenses and colonize and persist in the urinary tract. Enhanced secretion of IL-1β is protective in the Atg16L1HM mice with inhibition of IL-1 signaling leading to bacteriuria levels similar to those of the WT mice at 1 dpi, yet inhibition of IL-1 signaling in WT mice did not make the infection worse, suggesting that the level and timing of IL-1β secretion may be important. Given the high numbers of UTIs and the increasing antibiotic resistance among UPEC isolates, the potential of this new knowledge to contribute to development of new treatment regimens to elicit an effective immune response to UPEC could be vital.

Our data and that of others suggests that the hyperinflammatory responses observed by ATG16L1-deficiency17,18 can be damaging or protective in different mucosal environments in response to different stimuli15,49. This may explain why the T300A polymorphism in ATG16L1 is highly prevalent in the Caucasian population12 even though it increases susceptibility to Crohn's Disease12,13. Recent studies have shown that the proteins produced by the T300A (human) or T316A (mouse) variants of ATG16L1 are more easily degraded by caspase-3, resulting in reduced expression of ATG16L149,50. ATG16L1 deficiency in the gastrointestinal tract is thought to cause intestinal dysbiosis because of an aberrant pro-inflammatory response to commensal gut flora19,20,51. Our work suggests that aberrant pro-inflammatory responses to commensals in the gut may occur as a trade-off for productive responses to pathogens in other tissues. The improved function of macrophages and increased production of IL-1β in response to UPEC by the hypomorphic ATG16L1 suggests that humans with the T300A variant may be more protected against pathogens such as UPEC where increased IL-1β would help clear the infection. Future genomic studies to investigate the possibility of associations between the T300A mutation and common infections such as UTI will help to reveal the selective pressure on maintenance of polymorphisms in ATG16L1 in the human population.

METHODS

Mice, treatments and infections

All protocols were approved by the animal studies committee of the Washington University School of Medicine (Animal Welfare Assurance #A-3381-01). Mice were maintained in a barrier facility under pathogen-free conditions and a strict 12-hour light/dark cycle. Atg16L1HM and wild-type (WT) mice on a C57BL/6 background were used at 7-9 weeks of age for infection (females) or to obtain bone marrow-derived macrophages (males). Atg16L1HM mice were given two intraperitoneal (IP) injections of 100 mg/kg of clodronate-containing liposomes (clodrolip) or the equivalent amount of control liposomes: two days and again 30 minutes (min) before infection. Mice were given two IP injections of 1 mg of Anakinra (Kineret, Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Stockholm, Sweden) diluted in Dulbecco's Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS): 16 hours and again 30 min before infection. For infections, the UPEC strain UTI89 was grown statically for 17 hours in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C; anesthetized mice were transurethrally inoculated with 107 colony forming units (CFU) of UTI89 in 50 μl of PBS as previously described52. Urines from infected mice were collected at multiple time points, serially diluted in PBS, and plated on LB plates52. Three days post-infection, bladders were aseptically removed, homogenized in 0.1% Triton-X, serially diluted in PBS, and plated on LB plates21.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions from spleens were stained with the following antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or flourescent dyes at 1:100 dilutions unless stated: anti-mouse GR1 FITC, anti-mouse F4/80 PE, anti-mouse CD11b APC, anti-mouse CD45 Pacific Blue, and 7AAD (1:500, AnaSpec Inc., Fremont, CA). Cells were fixed with 1% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min with Actinomycin (ACROS Organics, Geel, Belgium). Stained cells were analyzed on a BD FACSCantoII using BD FACS DIVA software (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

Isolation, differentiation and challenge of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs)

Bone marrow was aseptically isolated from Atg16L1HM, Tlr4−/−, Nlrp3−/−, Nlrc4−/−, Aim2−/−, Nod2−/−, Nod2−/− ; Atg16L1HM, 129S6 (caspase-11−/−), Caspase-1/Caspase-11 double knockout, and WT mice and differentiated on non-tissue-culture-treated petri dishes for 7 days at 37°C with 5% ambient CO2 in DMEM with 15% FBS, 30% L929 conditioned media, 1% Glutamax, 1% Na-Pyruvate, and 1% Penicillin and Streptomycin. Then on day 7 post-isolation, non-attached cells were aspirated, and the media was changed to DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% Glutamax, and 1% Na-Pyruvate. On day 8, cells were incubated with ice-cold DPBS, removed with a cell scraper, counted, and plated at 5×105 cells/ml. On day 9, BMDMs were challenged with UTI89 or MG165525 grown as described above for mouse infections at a MOI of 0.1.

Intracellular bacteria quantification

Intracellular CFU were determined by serially diluting and plating cell lysates from BMDMs that had been challenged with bacteria for 1 or 2 hours and then treated with 100 μg/ml gentamicin for 15 min. For bacterial survival time course, BMDMs were challenged with UPEC for 2 hours, treated with 100 μg/ml gentamicin for 1 hour, and then 10 μg/ml gentamicin for the remaining time stated. For imaging analysis, cells were stained with rabbit anti-E.coli (1:500, US Biologicals, Swampscott, MA)21 and rat anti-LAMP1 (1:50, clone ID4B; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA)21, and antigen-antibody complexes were detected with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor-488-conjugated secondary antibody and anti-rat Alexa-594-conjugated secondary antibody (both at 1:500, Invitrogen; Carlsbad, CA). Images were obtained with a Zeiss Apotome microscope.

ELISAs

BMDMs were incubated with UTI89, CFT073, or MG1655 for 2 hours, then treated with 100 μg/ml gentamicin containing medium for 1 hour and finally incubated with 10 μg/ml gentamicin containing medium for 5 hours (8-hr samples) or 21 hours (24-hr samples) at which point the supernatant was collected for ELISAs. IL-1β DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), TNFα DuoSet ELISA kit (R&D systems) and Caspase-1 (mouse) matched pair detection set (Adipogen, San Diego, CA) were used according to manufacturer instructions. Where indicated, the following inhibitors were used throughout the experiment: the Cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074 Me (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., Farmingdale, NY) was used at 10 μM, the caspase-1 inhibitor Z WEHD-FMK (R&D systems) was used at 10 μM, and the VPS34 inhibitor 3-MA (Calbiochem, Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used at 2, 5 and 10 mM. Alum- and Silica-treated samples were pretreated with 100 ng/ml LPS(E. coli strain 055:B5, Sigma) for 2 hours, and then treated with 200 μg/ml of Inject Alum (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) or 100 μg/ml of Silica (Thermo Scientific) in fresh media for 6 hours. Streptolysin O (SLO) (Sigma) was used at 10 μg/ml with 10 mM DTT for 5 min, and then the medium was changed and collected 6 hours later.

qPCR

TRIzol (Invitrogen) was used to isolate RNA from 4×106 BMDMs that had been challenged with bacteria or LPS for 2 hours and then treated with gentamicin for 1 hour. RNA was treated with DNase1 (Ambion, Austin, TX), and Superscript II RNase H reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) was used to synthesize cDNA from 1 μg of total RNA. Gene expression was determined by calculating ΔΔ CT with values normalized to 36B4 RNA levels and then to values from PBS treated samples.

Western Blots

Protein was isolated from cells as described21. Briefly, cell lysates were electrophoresed on 4-20% Pierce Precise Protein Gels (Thermo Scientific) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies: rabbit-anti-ATG16L1 (1:500, Sigma) guineapig-anti-p62 (1:1000, Progen Biotechnik, Heidelberg, Germany), rabbit anti-Caspase-1 (1:5000, Dr. Gabriel Nuñez), rat anti-Caspase-11 (1:250, Sigma), rat anti-NLRP3 (1:250, R&D systems), and rabbit-anti-GAPDH (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Goat-anti-rabbit IgG-HRP, goat-anti-guinea pig IgG-HRP, and goat-anti-rat IgG-HRP secondaries (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) were used and detected by SuperSignal West Dura (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical analyses

For time-course experiments, two-way ANOVAs with matching were used with Bonferroni post-tests for individual time points. To determine significance between two samples, unpaired t-tests, paired t-tests or non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were performed by using Graph Prism software. A value of P < 0.05 was used as the cut off for statistical significance.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Herbert ‘Skip’ Virgin for Atg16L1HM mice, Drs. Deborah J. Frank, Jason C. Mills, and Ken Cadwell for comments, Kassandra Weber for technical support, Dr. Kyle Bauckman for assistance with western blotting, Dr. Robyn Klein for the Caspase1/11 double knockout mice, and Dr. Wandy Beatty, Director of Imaging Facility, Department of Molecular Microbiology, for TEM assistance. This work was funded in part by R01AI063331 and R01DK091191 (to GN), NIH KO8 HL09837305 (to JDS), T32 AI 007172 35 (to NOB), K99/R00 DK080643; P30 DK052574; and R01 DK100644 (to IUM).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

JWS, CW, and IUM designed the research; JWS did research; JT did the TEM enumeration; NOB did the immunostaining experiments; RS provided the clodronate-containing liposomes; GN provided Nlrp3, Aim2, and Nlrc4 knockout mouse bones; JDS provided technical support and conceptual advice; JWS and IUM analyzed data; and JWS, CW, and IUM wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material is linked to the online version of the paper at http://www.nature.com/mi

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests

REFERENCES

- 1.Dielubanza EJ, Schaeffer AJ. Urinary tract infections in women. The Medical clinics of North America. 2011;95:27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.023. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foxman B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2014;28:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.003. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song J, Abraham SN. Innate and adaptive immune responses in the urinary tract. European journal of clinical investigation. 2008;38(Suppl 2):21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02005.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2008.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schilling JD, Martin SM, Hung CS, Lorenz RG, Hultgren SJ. Toll-like receptor 4 on stromal and hematopoietic cells mediates innate resistance to uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:4203–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0736473100. doi:10.1073/pnas.0736473100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulett GC, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli virulence and innate immune responses during urinary tract infection. Current opinion in microbiology. 2013;16:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.005. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billips BK, et al. Modulation of host innate immune response in the bladder by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infection and immunity. 2007;75:5353–5360. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00922-07. doi:10.1128/IAI.00922-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunstad DA, Justice SS, Hung CS, Lauer SR, Hultgren SJ. Suppression of bladder epithelial cytokine responses by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:3999–4006. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3999-4006.2005. doi:10.1128/IAI.73.7.3999-4006.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loughman JA, Hunstad DA. Attenuation of human neutrophil migration and function by uropathogenic bacteria. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2011;13:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.017. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parzych KR, Klionsky DJ. An overview of autophagy: morphology, mechanism, and regulation. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2014;20:460–473. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5371. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. doi:10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:722–737. doi: 10.1038/nri3532. doi:10.1038/nri3532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampe J, et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nature genetics. 2007;39:207–211. doi: 10.1038/ng1954. doi:10.1038/ng1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rioux JD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nature genetics. 2007;39:596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. doi:10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broz P, Monack DM. Molecular mechanisms of inflammasome activation during microbial infections. Immunological reviews. 2011;243:174–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01041.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saitoh T, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature. 2008;456:264–268. doi: 10.1038/nature07383. doi:10.1038/nature07383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris J, et al. Autophagy controls IL-1beta secretion by targeting pro-IL-1beta for degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:9587–9597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorbara MT, et al. The protein ATG16L1 suppresses inflammatory cytokines induced by the intracellular sensors Nod1 and Nod2 in an autophagy-independent manner. Immunity. 2013;39:858–873. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.013. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lapaquette P, Bringer MA, Darfeuille-Michaud A. Defects in autophagy favour adherent-invasive Escherichia coli persistence within macrophages leading to increased pro-inflammatory response. Cellular microbiology. 2012;14:791–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01768.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadwell K, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. doi:10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadwell K, et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn's disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell. 2010;141:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, et al. Atg16L1 deficiency confers protection from uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:11008–11013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203952109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203952109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schilling JD, Machkovech HM, Kim AH, Schwendener R, Schaffer JE. Macrophages modulate cardiac function in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2012;303:H1366–1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00111.2012. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00111.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeisberger SM, et al. Clodronate-liposome-mediated depletion of tumour-associated macrophages: a new and highly effective antiangiogenic therapy approach. British journal of cancer. 2006;95:272–281. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603240. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engel D, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-producing dendritic cells are rapidly recruited to the bladder in urinary tract infection but are dispensable for bacterial clearance. Infection and immunity. 2006;74:6100–6107. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00881-06. doi:10.1128/IAI.00881-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blattner FR, et al. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lloyd AL, Rasko DA, Mobley HL. Defining genomic islands and uropathogen-specific genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189:3532–3546. doi: 10.1128/JB.01744-06. doi:10.1128/JB.01744-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franchi L, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nature immunology. 2012;13:325–332. doi: 10.1038/ni.2231. doi:10.1038/ni.2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latz E, Xiao TS, Stutz A. Activation and regulation of the inflammasomes. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2013;13:397–411. doi: 10.1038/nri3452. doi:10.1038/nri3452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Travassos LH, et al. Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nature immunology. 2010;11:55–62. doi: 10.1038/ni.1823. doi:10.1038/ni.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carneiro LA, Travassos LH. The Interplay between NLRs and Autophagy in Immunity and Inflammation. Frontiers in immunology. 2013;4:361. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00361. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2013.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kayagaki N, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. doi:10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miao EA, et al. Innate immune detection of the type III secretion apparatus through the NLRC4 inflammasome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:3076–3080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913087107. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913087107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sauer JD, et al. Listeria monocytogenes engineered to activate the Nlrc4 inflammasome are severely attenuated and are poor inducers of protective immunity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12419–12424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019041108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1019041108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miao EA, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nature immunology. 2010;11:1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. doi:10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harder J, et al. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome by Streptococcus pyogenes requires streptolysin O and NF-kappa B activation but proceeds independently of TLR signaling and P2X7 receptor. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:5823–5829. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900444. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0900444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hornung V, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nature immunology. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. doi:10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annual review of immunology. 2011;29:707–735. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weber K, Schilling JD. Lysosomes integrate metabolic-inflammatory cross-talk in primary macrophage inflammasome activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:9158–9171. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.531202. doi:10.1074/jbc.M113.531202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Luca A, et al. IL-1 receptor blockade restores autophagy and reduces inflammation in chronic granulomatous disease in mice and in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:3526–3531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322831111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322831111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marchiando AM, et al. A deficiency in the autophagy gene Atg16L1 enhances resistance to enteric bacterial infection. Cell host & microbe. 2013;14:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Starr T, et al. Selective subversion of autophagy complexes facilitates completion of the Brucella intracellular cycle. Cell host & microbe. 2012;11:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.12.002. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C, et al. NOD2 is dispensable for ATG16L1 deficiency-mediated resistance to urinary tract infection. Autophagy. 2014;10:331–338. doi: 10.4161/auto.27196. doi:10.4161/auto.27196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bokil NJ, et al. Intramacrophage survival of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: differences between diverse clinical isolates and between mouse and human macrophages. Immunobiology. 2011;216:1164–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.05.011. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sims JE, Smith DE. The IL-1 family: regulators of immunity. Nature reviews. Immunology. 2010;10:89–102. doi: 10.1038/nri2691. doi:10.1038/nri2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J, et al. Autophagy suppresses interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta) signaling by activation of p62 degradation via lysosomal and proteasomal pathways. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:4033–4040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280065. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.280065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plantinga TS, et al. Crohn's disease-associated ATG16L1 polymorphism modulates pro-inflammatory cytokine responses selectively upon activation of NOD2. Gut. 2011;60:1229–1235. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.228908. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.228908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buffen K, et al. Autophagy modulates Borrelia burgdorferi-induced production of interleukin-1beta (IL 1beta). The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:8658–8666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.412841. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.412841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ingersoll MA, Kline KA, Nielsen HV, Hultgren SJ. G-CSF induction early in uropathogenic Escherichia coli infection of the urinary tract modulates host immunity. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:2568–2578. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01230.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lassen KG, et al. Atg16L1 T300A variant decreases selective autophagy resulting in altered cytokine signaling and decreased antibacterial defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407001111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1407001111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murthy A, et al. A Crohn's disease variant in Atg16l1 enhances its degradation by caspase 3. Nature. 2014;506:456–462. doi: 10.1038/nature13044. doi:10.1038/nature13044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kostic AD, Xavier RJ, Gevers D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1489–1499. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.009. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hung CS, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ. A murine model of urinary tract infection. Nature protocols. 2009;4:1230–1243. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.116. doi:10.1038/nprot.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.