Abstract

Background: L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and ASC amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) have been associated with tumor growth and progression. However, the clinical significance of LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression in the prognosis of patients with lung adenocarcinoma remains unclear. Methods: In total, 222 patients with surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma were investigated retrospectively. Tumor sections were stained immunohistochemically for LAT1, ASCT2, CD98, phosphorylated mammalian target-of-rapamycin (p-mTOR), and Ki-67, and microvessel density (MVD) was determined by staining for CD34. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation status was also examined. Results: LAT1 and ASCT2 were positively expressed in 22% and 40% of cases, respectively. Coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was observed in 12% of cases and was associated significantly with disease stage, lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, CD98, Ki-67, and p-mTOR. Only LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression indicated a poor prognosis for lung adenocarcinoma. Furthermore, this characteristic was recognized in early-stage patients, especially those who had wild-type, rather than mutated, EGFR. Multivariate analysis confirmed that the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was an independent factor for predicting poor outcome. Conclusions: LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression is an independent prognostic factor for patients with lung adenocarcinoma, especially during the early stages, expressing wild-type EGFR.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, LAT1, ASCT2, coexpression, wild-type EGFR, prognostic factor

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death in the world. Despite years of research, the prognosis for patients with lung cancer remains dismal, with a 5-year survival rate of 14% [1]. Thus, assessing the potential of established biomarkers for predicting the outcome and the response to specific therapies is important to improve the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Tumor staging and performance status are currently the most powerful prognostic predictors in patients with NSCLC [2]. Recent large-scale studies demonstrated that sex, smoking history, and histology can affect the outcome after treatment in patients with NSCLC [3-5].

Among NSCLCs, lung adenocarcinoma is the most frequent, and its prognosis depends largely on the presence of mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene. This is because for patients with EGFR mutations, there are the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), molecularly targeted drugs which prolong overall survival markedly [6-9]. Thus, there is a continuing need for a new therapeutic target in patients with wild-type EGFR.

Amino acid transporters are necessary for tumor cell growth and proliferation, and the overexpression of amino acid transporters has been described as having an important role in the survival and metastasis of cancer cells [10-14]. Recently, it has been found that L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and ASC-type amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) were linked significantly to carcinogenesis and tumor pathogenesis [12,14-19].

LAT1 is a system L amino acid transporter that delivers large neutral amino acids, including essential amino acids, such as leucine, isoleucine, valine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, methionine, and histidine. It requires a covalent association with the heavy chain 4F2 antigen, which is a cell-surface antigen, also called CD98, for its functional expression on the plasma membrane [11,12]. It has been reported to be highly expressed in proliferating tissues, many tumor cell lines, and primary human neoplasms [12,17,19].

ASCT2 is a Na+-dependent transporter, responsible for the transport of small neutral amino acids, including glutamine, alanine, and serine, cysteine and threonine, and is a major glutamine transporter in human hepatoma cells [20]. It has recently been reported to be highly expressed in human tumors, such as hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal, prostate, and tongue cancers, and NSCLC [15,16,21,22].

LAT1 and ASCT2 provide cancer cells with essential amino acids for protein synthesis, and they coordinate tumor cell growth through the activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [13,20]. In an in vitro study, recently, LAT1 and ASCT2 were confirmed to be in close proximity to each other, followed by the suggestion that they could supply essential amino acids and glutamine to cells effectively [23,24]. It has been reported that the overexpression of LAT1 or ASCT2 is closely related to tumor aggressiveness and worse survival in a various human neoplasms.

To our knowledge, no clinicopathological study using clinical samples has assessed the effect of coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 on the prognosis and progression of NSCLC. Further study is warranted to identify the relationship between the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 and their prognostic roles after surgery in human neoplasms.

Thus, we conducted a clinicopathological study to evaluate the clinical significance of LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression in lung adenocarcinoma. The aim of this study was to clarify whether the coexpression of these markers is closely associated with the outcome after surgery and to explore the relationship between LAT1, ASCT2, and clinicopathological characteristics. We also examined the correlation of their protein expression with Ki-67 labeling index (LI), microvessel density (MVD), as determined by CD34, the phosphorylation of mTOR (p-mTOR), and expression of these markers according to EGFR mutation status.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board. We analyzed 236 consecutive patients with lung adenocarcinoma (pathological stage I-III) who underwent resection either by lobectomy or pneumonectomy with mediastinal lymph-node dissection at Gunma University Hospital (Maebashi, Gunma, Japan) between June 2003 and December 2010. Of these patients, 14 were excluded from further analysis because tissue specimens were not available.

Thus, 222 patients were enrolled in the study. No patient received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with platinum-based regimens and oral administration of tegafur (a fluorouracil derivative drug) were administered to six and 51 patients, respectively. There were 17 patients who used an EGFR-TKI as treatment after recurrence (gefitinib for 16 and erlotinib for 1).

The tumor specimens were classified histologically according to the World Health Organization criteria. The stages of pathological tumor-node-metastasis were established using the International System for Staging Lung Cancer, as adopted by the American Joint Committee on Cancer and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer [25]. The day of surgery was considered to be the first day after surgery. The follow-up duration ranged from 32 to 3821 (median, 1498) days.

Immunohistochemical staining

LAT1 expression was determined by immunohistochemical staining using a murine anti-human LAT1 monoclonal antibody 4A2 (provided by Dr. H. Endou (J-Pharma, Tokyo, Japan), 2 mg mL-1, dilution; 1:3200) [26]. The production and characterization of the LAT1 antibody have been described previously [16,18]. An affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA; 1:100 dilution) raised against the C-terminus of human CD98 was used to detect CD98. The detailed protocol for immunostaining was published elsewhere [17,19]. An affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., 1:300 dilution) was used to detect ASCT2. The production and characterization of the ASCT2 antibody have been described previously [21,22].

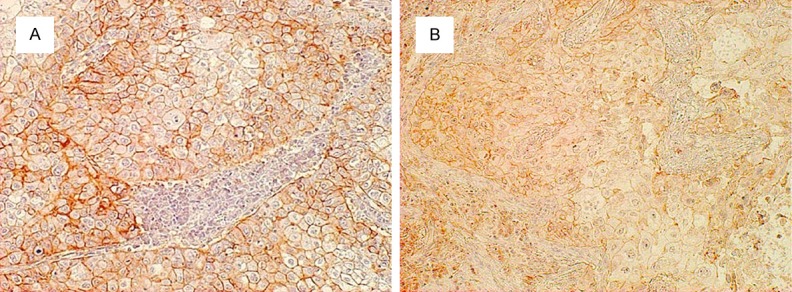

LAT1, CD98, and ASCT2 staining were considered positive only if distinct membrane staining was apparent. Their expression scores were assessed by the extent of staining: 1, ≤ 10% of the tumor area stained; 2, 11-25% stained; 3, 26-50% stained; and 4, ≥ 51% stained. Those tumors with a score ≥ 2 were deemed to be positive in expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissues. Immunohistochemical staining sections showed (A) positive L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1); and (B) positive ASC amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) expression in lung adenocarcinoma, respectively. The expression of LAT1 and ASCT2 were considered positive only if distinct membrane staining was present and their score represented more than two. The showed sections were from same patient, and the each score of LAT1 and ASCT2 were both four.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against CD34 (1:800 dilution; Nichirei Corp.) and Ki-67 (1:40; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and a rabbit monoclonal antibody against p-mTOR (1:80; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) were also used. The number of CD34-positive vessels was counted in four randomly selected regions in a ×400 field (0.26 mm2 field area). The MVD was defined as the mean number of microvessels per 0.26-mm2 field area, and tumors in which the number of stained tumor cells was greater than the median were defined as ‘high’ expressing. For Ki-67, epithelial cells with nuclear staining of any intensity were considered to be positive. Approximately 1000 nuclei were counted on each slide, and the proliferative activity was assessed as the percentage of Ki-67-stained nuclei (Ki-67 LI) in each sample. The median Ki-67 LI was evaluated, and tumors with an LI greater than the median were considered to be ‘high’ expressing. For p-mTOR, a semiquantitative scoring method was used: 1, ≤ 10%; 2, 11-25%; 3, 26-50%, 4, ≥ 51% of positive cells. Those tumors with a staining score > 3 were considered to be strongly stained [17,19]. All sections were assessed independently using light microscopy in a blinded manner by at least two of the authors.

DNA extraction and EGFR mutation analysis

After surgical removal, a portion of each sample was frozen immediately and stored at -80°C until DNA extraction. Genomic DNA was extracted from a 3-5-mm cube of tumor tissue using a DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and subsequently diluted to a concentration of 20 ng/µL. EGFR mutations in lung adenocarcinoma tissue were analyzed by PNA-enriched sequencing, as described previously [27].

Statistical analysis

P-values < 0.05 were considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the association between two categorical variables. The correlation between different variables was analyzed using the non-parametric Spearman’s rank test.

Elderly patients were defined as those over 65 years old, and an ‘ever smoker’ was defined as someone who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in his/her lifetime. Disease staging was divided into two groups: stage I and stages II-III. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival as a function of time, and survival differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. Overall survival (OS) was determined as the time from tumor resection to death by any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time between tumor resection and the first disease progression or death. Multivariate analysis was performed using a stepwise Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (ver. 21 for Windows; IBM Corp., NY, USA).

Results

Immunohistochemical analysis and clinicopathological features

In total, 222 primary lung adenocarcinoma lesions were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. The expression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was detected in carcinoma cells in tumor tissues and localized predominantly on the plasma membrane. All positive cells showed strong membranous staining. Positive expression of LAT1, CD98, and ASCT2 was recognized in 22% (48/222), 20% (45/222), and 40% (88/222) of all patients, respectively. LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression was observed in 12% (27/222).

The median number of CD34-positive vessels was 9 (range, 1-45), which was chosen as the cut-off point. The median Ki-67 LI was 8% (range, 1-92), which was used as the cut-off. ‘High’ expression of CD34 and Ki-67 LI was detected in 52% (115/222) and 55% (123/222), respectively. High expression of p-mTOR was observed in 32% (71/222) of the tumors.

LAT1 and ASCT2 expression and patient demographics

Patient characteristics based on LAT1 and ASCT2 expression are shown in Table 1. Positive LAT1 expression was significantly associated with sex, smoking, EGFR mutation status, disease stage, lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, CD98, Ki-67 LI, and p-mTOR, whereas positive ASCT2 expression was significantly associated with only three variables: T factor, CD98, and Ki-67 LI. LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression was significantly associated with smoking, disease stage, T factor, N factor, lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, CD98, Ki-67 LI, and p-mTOR. The coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was not associated with EGFR-TKI use in total patients, patients expressing wild-type EGFR, or patients with EGFR mutations (data not shown).

Table 1.

Patient’s demographics according to LAT1 and ASCT2

| LAT1 | ASCT2 | LAT1 and ASCT2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Variables | Total (n= 222) | Positive (n= 48) | Negative(n= 174) | P-value | Positive(n= 88) | Negative(n= 134) | P-value | Coexpression(n= 27) | Others(n= 195) | P-value |

| Age | ||||||||||

| <65 years/≥65 years | 76/146 | 15/33 | 61/113 | 0.623 | 27/61 | 49/85 | 0.366 | 7/20 | 69/126 | 0.332 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male/Female | 104/118 | 30/18 | 74/100 | 0.014 | 41/47 | 63/71 | 0.951 | 16/11 | 88/107 | 0.168 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Yes/No | 107/115 | 33/15 | 74/100 | 0.001 | 47/41 | 60/74 | 0.208 | 19/8 | 88/107 | 0.014 |

| EGFR mutation | ||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 98/124 | 13/35 | 85/89 | 0.007 | 40/48 | 58/76 | 0.750 | 8/19 | 90/105 | 0.105 |

| p-Stage | ||||||||||

| I/II-III | 164/58 | 27/21 | 137/37 | 0.002 | 62/26 | 102/32 | 0.347 | 13/14 | 151/44 | 0.001 |

| T factor | ||||||||||

| T1/T2-4 | 120/102 | 21/27 | 99/75 | 0.106 | 35/53 | 85/49 | 0.001 | 9/18 | 111/84 | 0.021 |

| N factor | ||||||||||

| N0/N1-2 | 174/48 | 33/15 | 141/33 | 0.067 | 67/21 | 107/27 | 0.511 | 17/10 | 157/38 | 0.038 |

| Lymphatic permeation | ||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 78/144 | 26/22 | 52/122 | 0.002 | 36/52 | 42/92 | 0.144 | 15/12 | 63/132 | 0.018 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 69/153 | 28/20 | 41/133 | <0.001 | 32/56 | 37/97 | 0.168 | 18/9 | 51/144 | <0.001 |

| CD98 | ||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 45/177 | 22/26 | 23/151 | <0.001 | 26/62 | 19/115 | 0.005 | 14/13 | 31/164 | <0.001 |

| Ki-67 | ||||||||||

| High/Low | 123/99 | 35/13 | 88/86 | 0.006 | 59/29 | 64/70 | 0.005 | 20/7 | 103/92 | 0.037 |

| CD34 | ||||||||||

| High/Low | 115/107 | 30/18 | 85/89 | 0.094 | 51/37 | 64/70 | 0.137 | 17/10 | 98/97 | 0.216 |

| p-mTOR | ||||||||||

| High/Low | 71/151 | 26/22 | 45/129 | <0.001 | 31/57 | 40/94 | 0.401 | 15/12 | 56/139 | 0.005 |

Abbreviations: ASCT2 = ASC amino acid transporter 2; LAT1 = L-type amino acid transporter 1; p-mTOR = phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin; p-stage = pathological stage. The bold entries show a statistically significant difference.

Correlation of LAT1 and ASCT2 expression with different biomarkers

On the basis of Spearman’s rank correlation, positive LAT1 expression showed a statistically significant correlation with CD98 and p-mTOR. LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression showed a statistically significant correlation with CD98. A weak but significant correlation was recognized between LAT1 and ASCT2. Positive ASCT2 expression also showed a weak but significant correlation with CD98 and Ki-67. In patients with stage I disease, positive LAT1 expression showed a statistically significant correlation with CD98, Ki-67, CD34, and p-mTOR, and positive ASCT2 expression showed a statistically significant correlation with Ki-67 and CD34. The coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 in patients with stage I disease showed statistically significant correlations with CD98 and CD34. However, there were no statistically significant correlations among these variables in patients at stages II-III. The significant correlations with Ki-67 and p-mTOR detected in patients with stage I disease were also seen in patients with stages II-III disease. In patients with wild-type EGFR, positive LAT1 expression was significantly correlated with ASCT2, CD98, Ki-67, CD34, and p-mTOR, and positive ASCT2 expression showed a significant correlation with CD98, Ki-67, and p-mTOR. Coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 in the patients with wild-type EGFR was significantly correlated with CD98 and p-mTOR. In contrast, there was no significant correlation between these variables in the patients with EGFR mutations, with the exception of significant correlations with Ki-67 and p-mTOR seen in both patients with and without EGFR mutations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between LAT1, ASCT2, and other biomarkers

| Biomarkers | Total (n= 222) | Stage I (n= 164) | Stage II-III (n= 58) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | EGFR mut (n= 98) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| |r| | P-value | |r| | P-value | |r| | P-value | |r| | P-value | |r| | P-value | |

| LAT1 - ASCT2 | 0.178 | 0.008 | 0.095 | 0.228 | 0.331 | 0.011 | 0.201 | 0.026 | 0.165 | 0.105 |

| LAT1 - CD98 | 0.334 | <0.001 | 0.404 | <0.001 | 0.197 | 0.138 | 0.352 | <0.001 | 0.221 | 0.029 |

| LAT1 - Ki-67 | 0.185 | 0.006 | 0.247 | 0.001 | 0.067 | 0.619 | 0.252 | 0.005 | 0.066 | 0.516 |

| LAT1 - CD34 | 0.112 | 0.095 | 0.231 | 0.003 | 0.193 | 0.148 | 0.259 | 0.004 | 0.114 | 0.262 |

| LAT1 - p-mTOR | 0.250 | <0.001 | 0.259 | 0.001 | 0.134 | 0.317 | 0.386 | <0.001 | 0.048 | 0.636 |

| ASCT2 - CD98 | 0.292 | 0.001 | 0.187 | 0.016 | 0.181 | 0.175 | 0.271 | 0.002 | 0.070 | 0.495 |

| ASCT2 - Ki-67 | 0.190 | 0.005 | 0.201 | 0.010 | 0.123 | 0.356 | 0.252 | 0.005 | 0.115 | 0.258 |

| ASCT2 - CD34 | 0.100 | 0.138 | 0.248 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.969 | 0.120 | 0.186 | 0.074 | 0.470 |

| ASCT2 - p-mTOR | 0.056 | 0.403 | 0.007 | 0.926 | 0.170 | 0.202 | 0.210 | 0.019 | 0.136 | 0.183 |

| LAT1/ASCT2 - CD98 | 0.292 | <0.001 | 0.368 | <0.001 | 0.180 | 0.177 | 0.301 | 0.001 | 0.230 | 0.023 |

| LAT1/ASCT2 - Ki-67 | 0.140 | 0.037 | 0.247 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.946 | 0.187 | 0.038 | 0.056 | 0.581 |

| LAT1/ASCT2 - CD34 | 0.083 | 0.217 | 0.238 | 0.002 | 0.231 | 0.081 | 0.150 | 0.097 | 0.018 | 0.858 |

| LAT1/ASCT2 - p-mTOR | 0.188 | 0.005 | 0.133 | 0.090 | 0.181 | 0.175 | 0.339 | <0.001 | 0.049 | 0.634 |

| Ki-67 - p-mTOR | 0.324 | <0.001 | 0.263 | 0.001 | 0.395 | 0.002 | 0.304 | 0.001 | 0.350 | <0.001 |

These biomarkers were examined by Spearman’s rank correlation test. Abbreviations: ASCT2 = ASC amino acid transporter 2; LAT1 = L-type amino acid transporter 1; p-mTOR = phosphorylated mammalian targe of rapamycin.

Patient mortality

The 5-year survival rate and median survival time for all patients were 73% and 3,542 days, respectively. Results of the univariate analysis are shown in Table 3. Worse prognosis after surgery was significantly associated with age, sex, smoking history, disease stage, lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, LAT1, ASCT2, coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2, Ki-67 LI, and CD34, as assessed by univariate analysis.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis in overall survival and progression-free survival

| Variables | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | EGFR mutation (n= 98) | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | EGFR mutation (n= 98) | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| 5-year survival rate (%) | P-value | 5-year survival rate (%) | P-value | 5-year survival rate (%) | P-value | 5-year survival rate (%) | P-value | 5-year survivalrate (%) | P-value | 5-year survivalrate (%) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| <65 years/≥65 years | 90/65 | <0.001 | 89/58 | 0.002 | 90/74 | 0.098 | 81/58 | 0.001 | 87/53 | 0.002 | 75/65 | 0.235 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male/Female | 68/78 | 0.026 | 60/77 | 0.053 | 86/78 | 0.908 | 64/68 | 0.224 | 60/68 | 0.232 | 72/67 | 0.992 |

| Smoking | ||||||||||||

| Yes/No | 66/80 | 0.005 | 59/80 | 0.010 | 83/80 | 0.924 | 56/74 | 0.004 | 56/75 | 0.028 | 57/74 | 0.117 |

| p-Stage | ||||||||||||

| I/II-III | 85/44 | <0.001 | 80/36 | <0.001 | 91/54 | 0.001 | 80/30 | <0.001 | 77/27 | <0.001 | 82/33 | <0.001 |

| Lymphatic permeation | ||||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 48/87 | <0.001 | 41/85 | <0.001 | 60/89 | 0.054 | 39/81 | <0.001 | 40/80 | <0.001 | 38/82 | <0.001 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 47/86 | <0.001 | 40/83 | <0.001 | 60/88 | 0.050 | 37/79 | <0.001 | 38/79 | <0.001 | 37/80 | 0.001 |

| LAT1 | ||||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 55/79 | 0.001 | 47/77 | 0.001 | 79/80 | 0.873 | 42/73 | 0.001 | 42/73 | 0.002 | 51/71 | 0.326 |

| ASCT2 | ||||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 63/80 | 0.011 | 56/76 | 0.012 | 71/85 | 0.417 | 49/74 | 0.007 | 49/74 | 0.013 | 57/75 | 0.258 |

| LAT1 and ASCT2 | ||||||||||||

| Coexpression/Others | 41/78 | <0.001 | 32/75 | <0.001 | 66/81 | 0.448 | 24/73 | <0.001 | 24/73 | <0.001 | 49/70 | 0.448 |

| CD98 | ||||||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 64/76 | 0.114 | 62/70 | 0.442 | 69/82 | 0.509 | 55/67 | 0.028 | 55/67 | 0.360 | 18/75 | 0.014 |

| Ki-67 | ||||||||||||

| High/Low | 62/86 | 0.002 | 57/80 | 0.012 | 68/92 | 0.034 | 51/82 | <0.001 | 52/78 | 0.009 | 52/86 | 0.002 |

| CD34 | ||||||||||||

| High/Low | 66/81 | 0.004 | 58/79 | 0.003 | 76/84 | 0.603 | 55/77 | 0.005 | 53/76 | 0.011 | 59/78 | 0.222 |

| p-mTOR | ||||||||||||

| High/Low | 64/78 | 0.082 | 57/72 | 0.118 | 71/85 | 0.319 | 47/71 | 0.002 | 47/71 | 0.063 | 49/79 | 0.013 |

Abbreviations: ASCT2 = ASC amino acid transporter 2; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; LAT1 = L-type amino acid transporter1; p-mTOR = phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin; p-stage = pathological stage. The bold entiries show a statistically significant difference.

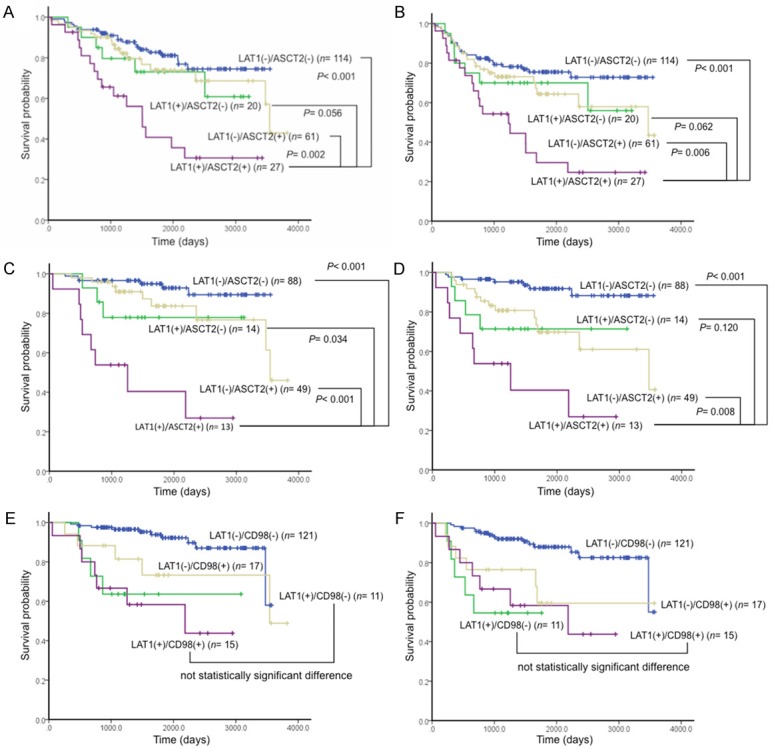

Next, we examined the relationship between LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression and survival. Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival stratified curves based on patients with LAT1 and ASCT2 double-positive, LAT1 single-positive, ASCT2 single-positive, and LAT1 and ASCT2 double-negative expression. Patients with double-positive expression of LAT1 and ASCT2 had markedly worse prognosis in terms of OS (Figure 2A) and PFS (Figure 2B), compared with those with single-positive expression. The same tendencies were seen in pathological stage I patients (Figure 2C, 2D). The coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 had a greater impact on stage I patients, in terms of both OS and PFS, than did that of LAT1 and CD98 (5-year survival rates: 40% vs. 58% for OS and 40% vs. 58% for PFS, respectively (Figure 2C-F).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to LAT1, ASCT2, and CD98 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. Statistically significant differences in OS and PFS were observed in the patients with LAT1 and ASCT2 double-positive expression in stages I-III (OS, A; PFS, B), and stage I (OS, C; PFS, D). Coexpression of LAT1 and CD98 did not show a statistically significant difference in patients with stage I, compared with LAT1 single-positive expression (OS, E; PFS, F).

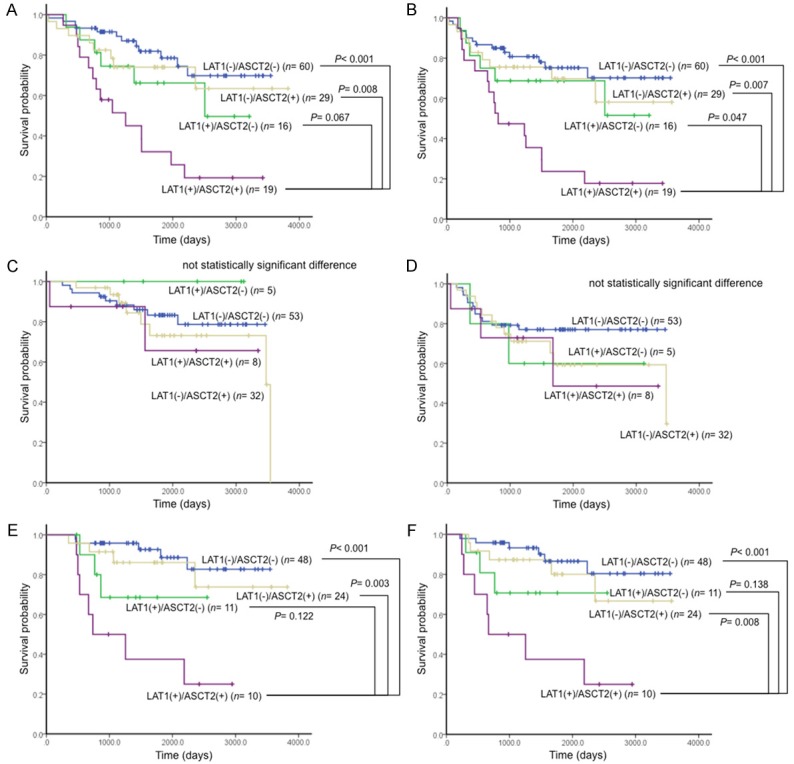

Moreover, we performed a survival analysis according to the presence or absence of EGFR mutations. In patients expressing wild-type EGFR, the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was a worse prognostic indicator, demonstrating a similar result as the patient survival data (Figure 3A, 3B). However, there was no statistically significant difference for patients in the EGFR mutation group (Figure 3C, 3D). Likewise, a statistically significant difference in survival was seen in wild-type EGFR patients with stage I disease (Figure 3E, 3F), but not in EGFR mutation patients (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) according to amino acid transporter expression (LAT1 and ASCT2) and EGFR mutation status. There were statistically significant differences in patients expressing wild-type EGFR (OS, A; PFS, B), but not in patients with EGFR mutations (OS, C; PFS, D). Likewise, there were statistically significant differences in wild-type EGFR patients with stage I disease (OS, E; PFS, F).

Finally, a multivariate analysis was performed for all patients. To confirm whether there was consistency in this population compared with previous studies, we performed separate analyses for LAT1, ASCT2, and their coexpression. ASCT2 was a significant independent prognostic factor for poor OS outcome (Table 4). LAT1 did not show a statistically significant difference according to multivariate analysis. We then confirmed that LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression was an independent prognostic factor for predicting poor OS as well as pathological stage. In patients with wild-type EGFR, coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 showed a similar result in OS as that of all patients, whereas it showed a tendency for a worse prognosis in PFS.

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis in overall survival and progression-free survival

| LAT1 | Overall survival | EGFR wild (n= 124) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male/Female | 1.252 0.577-2.715 | 0.569 | 0.879 0.328-2.357 | 0.798 | 0.702 0.363-1.358 | 0.293 | 0.607 0.242-1.523 | 0.287 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes/No | 1.540 0.699-3.394 | 0.284 | 2.201 0.759-6.378 | 0.146 | 2.263 1.142-4.486 | 0.019 | 2.419 0.902-6.486 | 0.079 |

| p-Stage | ||||||||

| I/II-III | 3.915 2.243-6.834 | <0.001 | 3.315 1.662-6.613 | 0.001 | 4.658 2.825-7.681 | <0.001 | 4.262 2.190-8.293 | <0.001 |

| LAT1 | ||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 1.289 0.715-2.326 | 0.399 | 1.414 0.689-2.899 | 0.345 | 1.117 0.655-1.904 | 0.685 | 1.248 0.631-2.469 | 0.524 |

|

| ||||||||

| ASCT2 | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male/Female | 1.464 0.695-3.086 | 0.316 | 1.023 0.390-2.680 | 0.964 | 0.786 0.409-1.511 | 0.469 | 0.679 0.274-1.678 | 0.401 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes/No | 1.474 0.697-3.117 | 0.310 | 1.960 0.690-5.566 | 0.206 | 2.119 1.087-4.134 | 0.028 | 2.166 0.818-5.737 | 0.120 |

| p-Stage | ||||||||

| I/II-III | 4.054 2.396-6.857 | <0.001 | 3.715 1.976-6.983 | <0.001 | 4.564 2.856-7.294 | <0.001 | 4.501 2.452-8.264 | <0.001 |

| ASCT2 | ||||||||

| Positive/Negative | 1.828 1.079-3.099 | 0.025 | 1.942 1.028-3.667 | 0.041 | 1.505 0.936-2.420 | 0.092 | 1.786 0.975-3.272 | 0.060 |

|

| ||||||||

| LAT1 and ASCT2 | Overall survival | Progression-free survival | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Variables | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | Total (n= 222) | EGFR wild (n= 124) | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | HR 95% CI | P-value | |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male/Female | 1.361 0.631-2.936 | 0.432 | 0.913 0.341-2.440 | 0.856 | 0.73 0.377-1.412 | 0.350 | 0.623 0.248-1.564 | 0.314 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Yes/No | 1.456 0.666-3.185 | 0.346 | 2.098 0.725-6.075 | 0.172 | 2.190 1.107-4.334 | 0.024 | 2.300 0.857-6.173 | 0.098 |

| p-Stage | ||||||||

| I/II-III | 3.642 2.098-6.322 | <0.001 | 3.186 1.648-6.159 | 0.001 | 4.447 2.718-7.275 | <0.001 | 3.940 2.084-7.450 | <0.001 |

| LAT1 and ASCT2 | ||||||||

| Coexpression/Others | 1.913 1.031-3.549 | 0.040 | 2.106 1.049-4.228 | 0.036 | 1.378 0.777-2.444 | 0.272 | 1.932 0.990-3.772 | 0.053 |

Abbreviations: ASCT2 = ASC amino acid transporter 2; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; LAT1 = L-type amino acid transporter 1; p-stage = pathological stage. The bold entries show a statistically significant difference.

Discussion

This is the first reported clinicopathological study to investigate the prognostic role of coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 in patients with surgically resected lung adenocarcinoma. Our results demonstrated that combined positive LAT1 and ASCT2 expression was a powerful negative prognostic indicator, compared with single-positive expression of LAT1 or ASCT2, especially in patients with stage I disease. Furthermore, we found that the coexpression had a meaningful effect on prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma with wild-type, but not mutated, EGFR. These observations suggest that the coexpression is important in early-stage wild-type EGFR lung adenocarcinoma. Considering our observations, the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 may play an important role in tumor progression and metastasis of early-stage wild-type EGFR lung adenocarcinoma. The seemingly close relationship between amino acid transporters and wild-type EGFR remains unclear. Further studies are needed to confirm and explain our results.

Kaira et al. reported that LAT1 expression is a promising pathological factor for the prediction of prognosis in patients with NSCLC [17], whereas Shimizu et al. showed an important role for ASCT2 expression in predicting poor prognosis in patients with pulmonary adenocarcinoma [22]. In our study, the expression frequency of ASCT2 was the same as that in a previous study (40% in both) [22], and multivariate analyses performed in both studies showed that ASCT2 positive expression was significantly different. Thus, this study was apparently consistent in terms of ASCT2 expression. The expression frequency of LAT1 in lung adenocarcinoma was also similar to that of a previous report (22% vs. 29%), but LAT1 did not show a statistically significant difference in the multivariate analysis in this study, unlike the previous report [17]. One difference is that they analyzed the significance of LAT1 expression in NSCLC, which consisted of 38% non-adenocarcinomas [17], whereas our investigation focused only on adenocarcinoma histology. It has been reported that the overexpression of LAT1 and CD98 is a meaningful prognostic indicator for patients with stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma [28]. This study focused on stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma, but the pathological role of ASCT2 expression in such patients remains unclear. The present study indicated that the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 contributed to predicting a poor outcome after surgery better than did LAT1 and CD98. There is no reported study comparing prognostic differences between LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression and LAT1 and CD98 coexpression. It would be useful to evaluate whether coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 is a more powerful marker for predicting poor prognosis than that of LAT1 and CD98.

In previous studies, prognostic significance was analyzed separately for LAT1 and ASCT2; thus, little is known about the prognostic role of LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression in primary human neoplasms, such as lung adenocarcinomas. We examined the prognostic role of these two amino acid transporters simultaneously. Compared with single-positive expression of LAT1 or ASCT2, the aggressiveness of tumor cells appeared higher in patients with double-positive expression of LAT1 and ASCT2. Tumor aggressiveness is thought to be closely related to cell proliferation, activation of the mTOR pathway, and tumor invasiveness into vessels or the lymphatic system. mTOR is a major regulator of cell size and tissue mass in both normal and diseased states, and glutamine is rate-limiting for mTORC1 activation by essential amino acids and growth factors [29-32]. Thus, it may be that the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 strongly contributes to malignant transformation.

LAT1 exchanges intracellular glutamine for extracellular neutral amino acids, including essential amino acids, which are used for cancer cell growth and proliferation. Intracellular glutamine is supplied mainly by ASCT2, because the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, which is one source of glutamine, does not function effectively in cancer cells because of the Warburg effect [33].

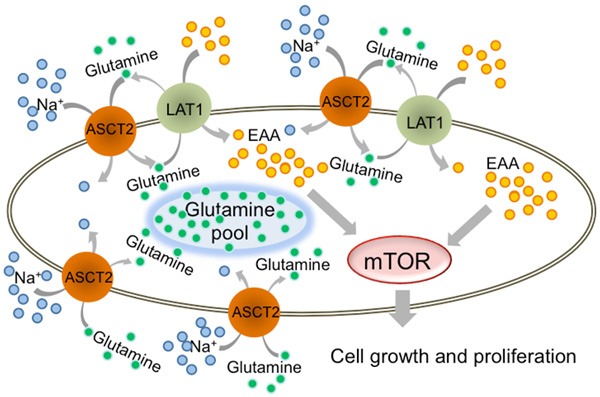

It is important for vigorous tumor growth and proliferation to incorporate glutamine without any intracellular shortage by exploiting another amino acid transporter. ASCT2 has been reported to play an important role in incorporating extracellular glutamine with Na+ into cells, and it is overexpressed in some cancer cells. Our results suggest that coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 could contribute to the supply of essential amino acids and glutamine in tumor cells, facilitating cancer cell expansion via the mTOR pathway [13,23,30]. These results are consistent with the mechanisms proposed by previous in vitro studies (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

LAT1 and ASCT2 coexpression promotes cell growth and proliferation in lung adenocarcinoma. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma cell growth and proliferation require mTOR signaling, which is regulated by essential amino acids (EAA). Intracellular uptake of EAA requires LAT1 and ASCT2. ASCT2 plays a role in storing glutamine intracellularly by contransport with Na+. Subsequently, LAT1 uses glutamine in EAA uptake.

The present study suggests that the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 was useful for predicting poor OS and PFS in patients expressing wild-type, but not mutated, EGFR. In our study, only 17 patients were treated with EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib and erlotinib, and the use of EGFR-TKIs did not affect the survival analysis according to the coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2. In particular, no patient received any EGFR-TKIs during the time from surgery to disease recurrence. Common malignancy factors, such as disease stage, lymphatic permeation, vascular invasion, and Ki-67 LI, also affected outcomes in the wild-type EGFR group, but these amino acid pathways did not affect poor outcomes in the EGFR mutation group.

It was reported by an in vitro study that EGFR mutant cancer cells differed from wild-type EGFR cells in that the mutated cells depended strongly on the EGFR signaling cascade for growth and proliferation, because of their ability to constitutively activate the EGFR signaling cascade [34]. It remains unclear why the presence of EGFR mutations causes this, but the signaling-dependent cascade might not require the LAT1/ASCT2 amino acid pathway.

For patients expressing wild-type EGFR, there is presently no effective treatment targeting lung adenocarcinomas. However, EGFR-TKIs, such as gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib, have shown a significant impact on prolonging survival of patients with EGFR mutations [35-38]. There is a continuing need for a new and effective molecularly targeted drug treatments, including adjuvant therapies, in patients without EGFR mutations.

Although adjuvant chemotherapy, including cisplatin-based combination regimens, after surgery is the current standard of care, based on the results of phase III trials in patients with stage II-III NSCLC [39-41], adjuvant chemotherapy using cisplatin-based regimens remains controversial for patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Thus, the investigation of potential markers for adjuvant therapy is important for the treatment of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma.

Several authors have reported that the inhibition of LAT1 leads to apoptosis by inducing intracellular depletion of amino acids required for the growth of cancers and inducing cell-cycle arrest at the G1 phase [42,43]. These investigations suggested that inhibition of LAT1 could be an effective therapeutic target for human neoplasms. Moreover, an experimental study showed that inhibition of ASCT2 reduced the availability of glutamine and other amino acids transported by ASCT2, and this could inhibit the survival of cancer cells via increased glutamine metabolism [44]. Thus, ASCT2 could also be a potential target for anticancer therapeutics. In the light of our data, these molecules offer therapeutic candidate targets for adjuvant therapy after surgical treatment of patients expressing LAT1, ASCT2 and wild-type EGFR, especially during the early stages.

Our study has several limitations. One was that it was a single-center cohort design, which may have biased the results. However, our study is the largest reported using the single histology, lung adenocarcinoma. Another limitation is that the optimal cut-off values for the expression levels of LAT1 and ASCT2 remain unclear. Previous studies revealed a strong correlation between the two transporters and their obligate chaperone [13,23,29]. However, the present study showed a relatively low percentage of correlation between LAT1 and ASCT2 expression. This discrepancy may be due to the qualities of the antibodies and the expression level measurements. This is a general limitation of immunohistochemical studies. Further study is warranted to investigate the most appropriate cut-off levels for these amino acid transporters.

In conclusion, coexpression of LAT1 and ASCT2 is a powerful and promising pathological marker predicting a worse outcome after thoracic surgery, and it is significantly associated with lung adenocarcinoma aggressiveness and proliferation. Thus, the LAT1 and ASCT2 may be potential targets for anticancer therapies in lung adenocarcinoma, especially in patients with wild-type EGFR and early stage disease.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Spira A, Ettinger DS. Multidisciplinary management of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:379–392. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brundage MD, Davies D, Mackillop WJ. Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer: a decade of prognosis. Chest. 2002;122:1037–1057. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawaguchi T, Takada M, Kubo A, Matsumura A, Fukai S, Tamura A, Saito R, Kawahara M, Maruyama Y. Gender, histology, and time of diagnosis are important factors for prognosis: analysis of 1499 never-smokers with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in Japan. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1011–1017. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181dc213e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura H, Ando K, Shinmyo T, Morita K, Mochizuki A, Kurimoto M, Tatsunami S. Female gender is an independent prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;17:469–480. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.10.01637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogure Y, Ando M, Saka H, Chiba Y, Yamamoto N, Asami K, Hirashima T, Seto T, Nagase S, Otsuka K, Yanagihara K, Takeda K, Okamoto I, Aoki T, Takayama K, Yamasaki M, Kudoh S, Katakami N, Miyazaki M, Nakagawa K. Histology and smoking status predict survival of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Results of West Japan Oncology Group (WJOG) Study 3906L. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:753–758. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31828b51f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitsudomi T, Kosaka T, Endoh H, Horio Y, Hida T, Mori S, Hatooka S, Shinoda M, Takahashi T, Yatabe Y. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor gene predict prolonged survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:2513–2520. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.00.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han SW, Kim TY, Jeon YK, Hwang PG, Im SA, Lee KH, Kim JH, Kim DW, Heo DS, Kim NK, Chung DH, Bang YJ. Optimization of patient selection for gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer by combined analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation, K-ras mutation, and Akt phosphorylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2538–2544. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim KS, Jeong JY, Kim YC, Na KJ, Kim YH, Ahn SJ, Baek SM, Park CS, Kim YI, Lim SC, Park KO. Predictors of the response to gefitinib in refractory non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2244–2251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takano T, Ohe Y, Sakamoto H, Tsuta K, Matsuno Y, Tateishi U, Yamamoto S, Nokihara H, Yamamoto N, Sekine I, Kunitoh H, Shibata T, Sakiyama T, Yoshida T, Tamura T. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and increased copy numbers predict gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:6829–6837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen HN. Role of amino acid transport and countertransport in nutrition and metabolism. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:43–77. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto Ki, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23629–23632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanagida O, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Segawa H, Nii T, Cha SH, Matsuo H, Fukushima J, Fukasawa Y, Tani Y, Taketani Y, Uchino H, Kim JY, Inatomi J, Okayasu I, Miyamoto K, Takeda E, Goya T, Endou H. Human L-type amino-acid transporter 1 (LAT1): characterization of function and expression in tumor cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1514:291–302. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: Partners in crime? Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:254–266. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baek S, Choi CM, Ahn SH, Lee JW, Gong G, Ryu JS, Oh SJ, Bacher-Stier C, Fels L, Koglin N, Hultsch C, Schatz CA, Dinkelborg LM, Mittra ES, Gambhir SS, Moon DH. Exploratory clinical trial of (4S)-4-(3-[18F] fluoropropyl)-L-glutamate for imaging xC- transporter using positron emission tomography in patients with non-small cell lung or breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5427–5437. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitte D, Ali N, Carlson N, Younes M. Overexpression of the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2555–2557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li R, Younes M, Frolov A, Wheeler TM, Scardino P, Ohori M, Ayala G. Expression of neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human prostate. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3413–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Hisada T, Tanaka S, Ishizuka T, Kanai Y, Endou H, Nakajima T, Mori M. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression in resectable stage I-III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:742–748. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Takahashi T, Nakagawa K, Ohde Y, Okumura T, Murakami H, Shukuya T, Kenmotsu H, Naito T, Kanai Y, Endo M, Kondo H, Nakajima T, Yamamoto N. LAT1 expression is closely associated with hypoxic markers and mTOR in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2011;3:468–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaira K, Sunose Y, Arakawa K, Ogawa T, Sunaga N, Shimizu K, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Itoh H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Segawa A, Furuya M, Mori M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression in surgically resected pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:632–638. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs BC, Finger RE, Onan MC, Bode BP. ASCT2 silencing regulates mammalian target of rapamycin growth and survival signaling in human hepatoma cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C55–C63. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00330.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toyoda M, Kaira K, Ohshima Y, Ishioka NS, Shino M, Sakakura K, Takayasu Y, Takahashi K, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Oyama T, Chikamatsu K. Prognostic significance of amino-acid transporter expression (LAT1, ASCT2, and xCT) in surgically resected tongue cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2506–2513. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimizu K, Kaira K, Tomizawa Y, Sunaga N, Kawashima O, Oriuchi N, Tominaga H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Yamada M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. ASC amino-acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) as a novel prognostic marker in non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2030–2039. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu D, Helmer ME. Metabolic activation-related CD147-CD98 comoplex. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1061–1071. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400207-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenczik CA, Sethi T, Ramos JW, Hughes PE, Ginsberg MH. Complementation of dominant suppression implicates CD98 in integrin activation. Nature. 1997;390:81–85. doi: 10.1038/36349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mountain CF. Revision in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest. 1997;11:1710–1717. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakata T, Ferdous G, Tsuruta T, Satoh T, Baba S, Muto T, Ueno A, Kanai Y, Endou H, Okayasu I. L-type amino acid transporter 1 as a novel biomarker for high-grade malignancy in prostate cancer. Pathol Int. 2009;59:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyamae Y, Shimizu K, Mitani Y, Araki T, Kawai Y, Baba M, Kakegawa S, Sugano M, Kaira K, Lezhava A, Hayashizaki Y, Yamamoto K, Takeyoshi I. Mutation detection of epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS genes using the smart amplification process version 2 from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung cancer tissue. J Mol Diagn. 2010;12:257–264. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Hisada T, Ishizuka T, Kanai Y, Nakajima T, Mori M. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and 4F2 heavy chain (CD98) expression in stage I pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2008;66:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicklin P, Bergman P, Zhang B, Triantafellow E, Wang H, Nyfeler B, Yang H, Hild M, Kung C, Wilson C, Myer VE, MacKeigan JP, Porter JA, Wang YK, Cantley LC, Finan PM, Murphy LO. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bodine SC, Stitt TN, Gonzalez M, Kline WO, Stover GL, Bauerlein R, Zlotchenko E, Scrimgeour A, Lawrence JC, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD. Akt/mTOR pathway is a crucial regulator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and can prevent muscle atrophy in vivo. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1014–1019. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohanna M, Sobering AK, Lapointe T, Lorenzo L, Praud C, Petroulakis E, Sonenberg N, Kelly PA, Sotiropoulos A, Pende M. Atrophy of S6K1(-/-) skeletal muscle cells reveales distinct mTOR effectors for cell cycle and size control. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:286–294. doi: 10.1038/ncb1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signaling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;41:424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koppenol WH, Bounds PL, Dang CV. Otto Warburg’s contributions to current concepts of cancer metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:325–337. doi: 10.1038/nrc3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okabe T, Okamoto I, Tamura K, Terashima M, Yoshida T, Satoh T, Takada M, Fukuoka M, Nakagawa K. Differential constitutive activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small cell lung cancer cells bearing EGFR gene mutation and amplification. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2046–53. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Sugawara S, Oizumi S, Isobe H, Gemma A, Harada M, Yoshizawa H, Kinoshita I, Fujita Y, Okinaga S, Hirano H, Yoshimori K, Harada T, Ogura T, Ando M, Miyazawa H, Tanaka T, Saijo Y, Hagiwara K, Morita S, Nukiwa T North-East Japan Study Group. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, Vergnenegre A, Massuti B, Felip E, Palmero R, Garcia-Gomez R, Pallares C, Sanchez JM, Porta R, Cobo M, Garrido P, Longo F, Moran T, Insa A, De Marinis F, Corre R, Bover I, Illiano A, Dansin E, de Castro J, Milella M, Reguart N, Altavilla G, Jimenez U, Provencio M, Moreno MA, Terrasa J, Muñoz-Langa J, Valdivia J, Isla D, Domine M, Molinier O, Mazieres J, Baize N, Garcia-Campelo R, Robinet G, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Lopez-Vivanco G, Gebbia V, Ferrera-Delgado L, Bombaron P, Bernabe R, Bearz A, Artal A, Cortesi E, Rolfo C, Sanchez-Ronco M, Drozdowskyj A, Queralt C, de Aguirre I, Ramirez JL, Sanchez JJ, Molina MA, Taron M, Paz-Ares L Spanish Lung Cancer Group in collaboration with Groupe Français de Pneumo-Cancérologie and Associazione Italiana Oncologia Toracica. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takano T, Fukui T, Ohe Y, Tsuta K, Yamamoto S, Nokihara H, Yamamoto N, Sekine I, Kunitoh H, Furuta K, Tamura T. EGFR mutations predict survival benefit from gefitinib in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma: a historical comparison of patients treated before and after gefitinib approval in Japan. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:5589–5595. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.7254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, O’Byrne K, Hirsh V, Mok T, Geater SL, Orlov S, Tsai CM, Boyer M, Su WC, Bennouna J, Kato T, Gorbunova V, Lee KH, Shah R, Massey D, Zazulina V, Shahidi M, Schuler M. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutaitons. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, Stephens RJ, Dunant A, Torri V, Rosell R, Seymour L, Spiro SG, Rolland E, Fossati R, Aubert D, Ding K, Waller D, Le Chevalier T LACE Collaborative Group. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:3552–3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douillard JY, Tribodet H, Aubert D, Shepherd FA, Rosell R, Ding K, Veillard AS, Seymour L, Le Chevalier T, Spiro S, Stephens R, Pignon JP LACE Collaborative Group. Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: subgroup analysis of the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:220–228. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c814e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.NSCLC Meta-analyses Collaborative Group. Arriagada R, Auperin A, Burdett S, Higgins JP, Johnson DH, Le Chevalier T, Le Pechoux C, Parmar MK, Pignon JP, Souhami RL, Stephens RJ, Stewart LA, Tierney JF, Tribodet H, van Meerbeeck J. Adjuvant chemotherapy, with or without postoperative radiotherapy, in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: two meta-analyses of individual patient data. Lancet. 2010;375:1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu XM, Reyna SV, Ensenat D, Peyton KJ, Wang H, Schafer AI, Durante W. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates LAT1 gene expression in vascular smooth muscle: Role in cell growth. FASEB J. 2004;18:768–770. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0886fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim CS, Moon IS, Park JH, Shin WC, Chun HS, Lee SY, Kook JK, Kim HJ, Park JC, Endou H, Kanai Y, Lee BK, Kim do K. Inhibition of L-type amino acid transporter modulates the expression of cell cycle regulatory factors in KB oral cancer cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2010;33:1117–1121. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oppedisano F, Catto M, Koutentis PA, Nicolotti O, Pochini L, Koyioni M, Introcaso A, Michaelidou SS, Carotti A, Indiveri C. Inactivation of the glutamine/amino acid transporter ASCT2 by 1,2,3-dthiazoles: proteoliposomes as a tool to gain insights in the molecular mechanism of action and of antitumor activity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;93:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]