Abstract

Aim: Amino acid transporters are essential for the growth, progression and the pathogenesis of various cancers. However, it remains obscure about the clinicopathological significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and system ASC amino acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) for patients with human ovarian tumors. The aim of this study is to elucidate the prognostic role of these amino acid transporters in ovarian tumor. Methods: One-hundred forty-two patients with surgically resected ovarian tumors were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Expression of LAT1, ASCT2, CD98, Ki-67 and microvessel density (MVD) determined by CD34 were evaluated using specimens of the resected tumors. Results: LAT1 and ASCT2 were positively expressed in 39% and 53%, respectively, of ovarian tumors (n=142) and 50% and 57%, respectively, of epidermal ovarian cancers (n=107). A positive LAT1 expression was closely correlated with the expression for ASCT2 and CD98, and cell proliferation (Ki-67) in ovarian cancer. By multivariate analysis, LAT1 was clarified as a significant independent marker for predicting a poor overall survival (OS). The expression of LAT1 could clearly discriminate between epidermal ovarian cancer and borderline malignancy. The expression level of LAT1 within ovarian cancer cells varied among serous adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma and we found LAT1 expression was higher in clear cell adenocarcinoma than other histological types. Conclusions: LAT1 is highly expressed in various ovarian tumors and a positive LAT1 expression can serve as a significant independent factor for predicting a poor OS in patients with epidermal ovarian cancer.

Keywords: LAT1, ASCT2, ovarian cancer, amino acid transporter, prognosis

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among women in the worldwide. It is difficult to characterize ovarian cancer at an early-stage due to a lack of specific symptoms. Therefore, most ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed at advanced stage, spreading the abdomen with ascites [1]. To improve the outcome of patients with ovarian cancer, it is important to assess the potential of established molecular markers for predicting prognosis and the efficacy to specific therapeutics. But, there were no established clinical markers which have correlated with prognosis and therapeutic efficacy in patients with human ovarian neoplasms.

Amino acid transporters are essential for the tumor growth and progression, and the overexpression of them has been clarified to play an important role in the survival and metastasis of cancer cells [2-4]. L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) is an L-type amino acid transporter that transports large neutral amino acids and requires covalent association with the heavy chain of 4F2 cell surface antigen (4F2hc/CD98) for its functional expression in plasma membrane [2,3]. It has been already proven to be highly expressed in proliferating tissues, various tumor cell lines and primary human cancers [3,4]. System ASC amino acid transporter-2 (ASCT2) is a Na+-dependent transporter responsible for transport of neutral amino acids including glutamine, leucine and isoleucine, and is a major glutamine transporter in human hepatoma cells [5-7]. Recent experimental studies disclosed that LAT1 and ASCT2 were linked to the carcinogenesis and tumor pathogenesis [5-7]. The protein expression level of these transporters has been identified as a significant marker for predicting a poor prognosis and malignant aggressiveness with various human cancers [4,8-14].

However, it remains obscure whether LAT1 and ASCT2 have a close relationship with the tumor development and aggressiveness in human ovarian tumors. Here, we conducted the clinicopathological study to examine the prognostic significance of LAT1 and ASCT2 in patients with ovarian tumors. In the present study, we focus on the clinicopathological significance of LAT1 expression for patients with ovarian cancer. In addition, the expression of Ki-67 labelling index and angiogenic markers such as microvessel density (MVD) determined by CD34 were also investigated by immunohistochemistry.

Materials and methods

Patients

Between February 2000 and January 2008, we analyzed 146 consecutive patients with ovarian tumors who underwent surgical resection at Gunma University Hospital. Four patients were excluded because no adequate specimen was available for the immunohistochemical study. Therefore, 142 patients were analyzed in this study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board.

Pathological stage and histological subtype were determined for each surgical specimen according to 2002 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) criteria, and Pathology and Genetics Tumors of the Breast and Female Genital Organs (World Health Organization, WHO 2003). None of the patients were treated with preoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy. As postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy, 97 patients received any regimens. Out of these 97 patients, 84 patients were treated with carboplatin plus paclitaxel, 7 patients with irinotecan plus mitomycin C, 2 patients with cisplatin plus doxorubicin, 2 patients with cisplatin and 2 patients with combination of cisplatin, etoposide and peplomycin.

Immunohistochemical staining

The LAT1 expression was determined using immunohistochemical staining with an anti-human LAT1 antibody (1.6 mg/mL, anti-human monoclonal mouse IgG1, KM3149, provided by Kyowa Hakko Co., Ltd.; dilution of 1:800). The production and characterization of the LAT1 antibody have been previously described [8,9,12]. The anti-CD98 antibody is an affinity purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., 1:100 dilution) raised against a peptide mapping at the carboxy-terminus of CD98 of human origin. The anti-CD98 antibody clearly detects 4F2hc, and the antigen is SLC3A2/4F2hc/CD98hc. The anti-ASCT2 antibody is an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:300 dilution). The detailed protocol for immunostaining has been published elsewhere [14]. The expression levels of LAT1, CD98 and ASCT2 were assessed based on the degree of staining, as follows: score 1, ≤10% of tumor area stained; score 2, 11-25% stained; score 3, 26-50% stained; and score 4, ≥51% stained. Tumors in which the stained tumor cells were scored as 1 were defined as negative, whereas those with scores of 2, 3 or 4 were defined as positive.

Immunohistochemical staining for CD34 and Ki-67 was performed according to procedures described in previous reports [12,14]. The following antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal antibodies against CD34 (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan, 1:800 dilution) and Ki-67 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark, 1:40 dilution). The number of CD34-positive vessels was counted in four selected hot spots in a x400 field (0.26 mm2 field area). The microvessel density (MVD) was defined as the mean number of microvessels per 0.26 mm2 field area. The median number of CD34-positive vessels was determined, and tumors in which the number of stained tumor cells was greater than the median value were defined as having a high expression. For Ki-67, highly cellular areas on the immunostained sections were evaluated. All tumor cells with nuclear staining of any intensity were defined as exhibiting a high expression. Approximately 1,000 nuclei were counted on each slide. The proliferative activity was assessed as the percentage of Ki-67-stained nuclei (Ki-67 labelling index) in the sample. The median Ki-67 labelling index was calculated, and tumors in which the number of stained tumor cells was greater than the median value were defined as having a high expression. The sections were assessed using light microscopy in a blinded fashion by at least two of the authors.

Statistical analysis

Probability values of <0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference. Fisher’s exact test was used to examine the association of two categorical variables. The correlation between different variables was analyzed using the nonparametric Spearman’s rank test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate survival as a function of time, and survival differences were analyzed by the log-rank test. Overall survival (OS) was determined as the time from tumor resection to death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time between tumor resection and the first disease progression or death. Multivariate analyses were performed using stepwise Cox proportional hazards model to identify independent prognostic factors. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 8 (SAS, Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for Windows.

Results

Patient demographics

We analyzed one hundred and forty-two patients with ovarian tumors including ovarian borderline malignancy. The median age of the patients was 55 years, ranging from 17 to 83 years. The histology of all patients (n=142) consists of 107 surface epithelial-stromal cancers, 27 borderline malignancies and 8 others. Out of 107 surface epithelial-stromal cancers, there were 30 patients (28%) with serous adenocarcinoma (SA), 13 patients (12%) mucinous adenocarcinoma (MA), 26 patients (24%) endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EA), 32 patients (30%) clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCA), 5 patients (8%) undifferentiated carcinoma and 1 patient malignant Brenner tumor (1%).

Out of 26 borderline malignancies, there were 9 patients with serous cystic tumor, 13 patients mucinous cystic tumor, 2 patients mixed epithelial tumor including endometrioid and clear cell tumor and 2 patients Brenner tumor. In the remaining 9 tumors, there were 3 sex cord/stromal tumors and 5 germ cell tumors and 1 masodermal mixed tumor. The day of surgery was considered as the start day for measuring postoperative survival. The median follow-up duration for all patients was 2173 days (range, 101 to 5290 days).

Immunohistochemical analysis

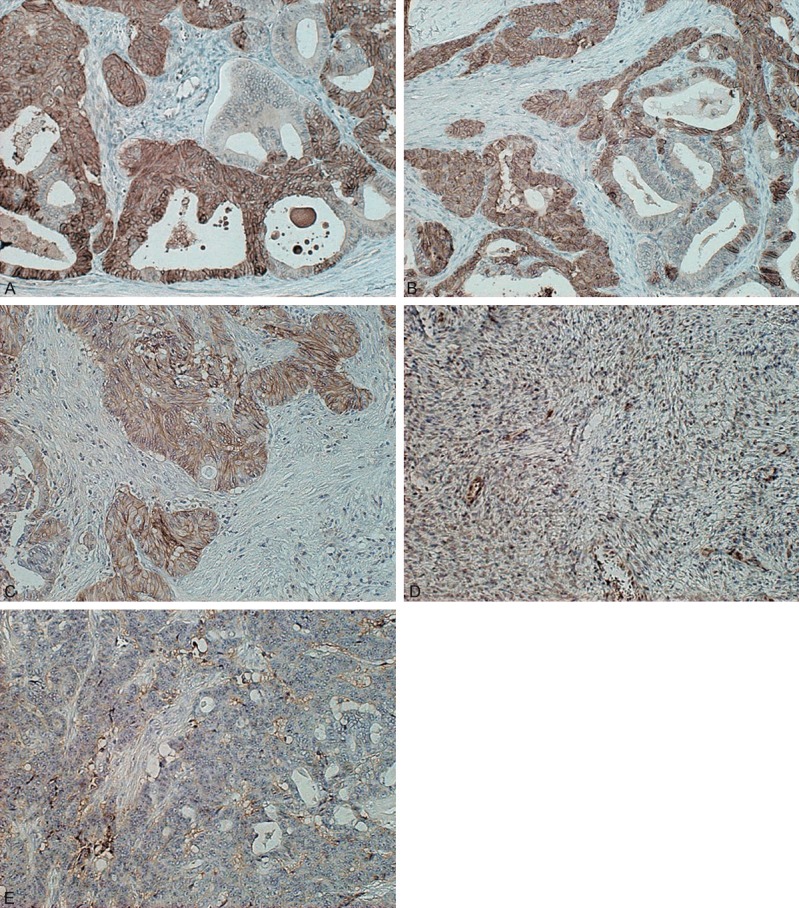

Immunohistochemical analyses were done using 142 primary sites of ovarian tumors. Figure 1 shows the representative pictures of LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98. LAT1 immunostaining was detected in the ovarian cancer cells, localized predominantly on the plasma membrane. All positive cells exhibited strong membranous immunostaining, and cytoplasmic staining was rarely evident. The rates of a positive expression and average scores for LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98 were 39% (56/142), 53% (75/142) and 39% (56/142) and 1.8±1.1, 2.1±1.1 and 1.7±0.9, respectively, in all patients. The rate of a positive expression was significantly higher for ASCT2 than for LAT1 and CD98 (P=0.032). In 107 patients with epidermal ovarian cancer, the rates of a positive expression and average scores for LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98 were 50% (53/107), 57% (61/107) and 46% (49/107) and 2.0±1.2, 2.1±1.1 and 1.8±1.0, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of a positive expression among LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98. In 27 patients with borderline malignancies, whereas, LAT1, CD98 and ASCT2 yielded a positive rate of 0% (0/27), 11% (3/27) and 52% (14/27), respectively, and an average score of 1.0±0.0, 1.1±0.3 and 2.1±1.1, respectively. The rate of a positive expression for ASCT2 achieved a significantly higher compared to that for LAT1 (P<0.001) and CD98 (P=0.003). The cut-off points for a high CD34 expression and high Ki-67 labelling index were determined based on the results of the analysis of the ovarian tumor tissues. The median number of CD34-positive vessels was 11 (range, 1-30), and a value of eleven was chosen as the cut-off point. The median Ki-67 labelling index was 16% (range, 1-88), and a value of 16% was chosen as the cut-off point. A high Ki67 expression and high CD34 expression were identified in 50% (71/142) and 44% (62/142) of the samples, respectively.

Figure 1.

Representative immunohistochemical staining of LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98 in epidermal ovarian cancer. Immunostaining of LAT1 (A), ASCT2 (B) and CD98 (C) displays a membranous immunostaining pattern in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma. There is no evidence of LAT1 immunostaining in serous papillary cystic tumor borderline (D) and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (E).

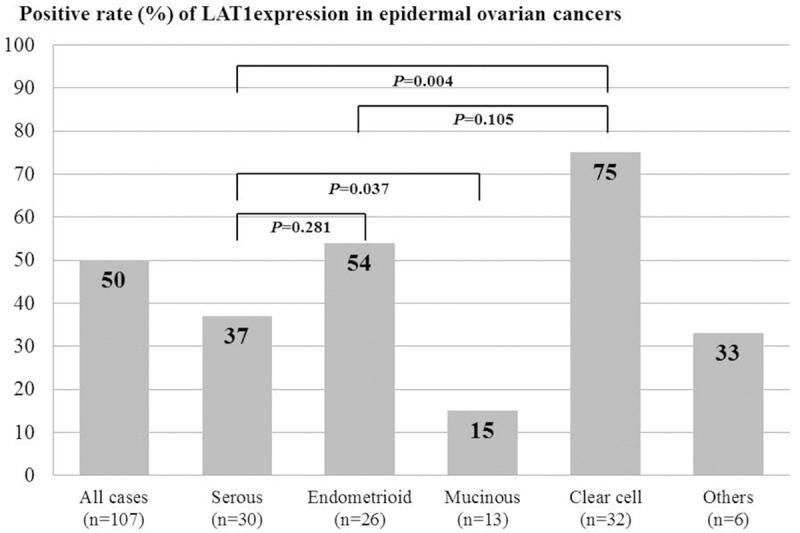

Next, we analyzed the clinicopathological features of ovarian tumors according to the expression of LAT1 (Table 1). A positive LAT1 expression was significantly associated with age, epidermal ovarian cancer, the positive expression of ASCT1 and CD98, cell proliferation (Ki-67 labelling index), angiogenesis (MVD determined by CD34) and adjuvant chemotherapy. In patients with epidermal ovarian cancer, however, the positive expression of LAT1 was closely related to a positive CD98 expression alone (Table 1, online only). We compared the expression level of LAT1 among patients with epidermal ovarian cancers (n=107) (Figure 2). The rates of a positive expression and average scores for LAT1 were 37% (11/30) and 1.4±0.5, respectively, in SA, 75% (24/32) and 2.8±1.2, respectively, in CCA, 15% (2/13) and 1.4±0.9, respectively, in MA, 54% (14/26) and 2.1±1.2, respectively, in EA and 33% (2/6) and 1.7±1.2, respectively, in the other tumors. The rate of a positive LAT1 expression was significantly higher in CCA than in SA, MA and others, demonstrating no significant difference between CCA and EA. The expression of LAT1 yielded a higher positive rate in SA and EA than in MA.

Table 1.

Patient’s demographics according to LAT1 expression in ovarian tumors (N=142)

| Variables | Total (n=142) | LAT1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Positive (n=56) | Negative (n=86) | p-value | |||

| Age | ≤50/>50 yr | 57/95 | 16/40 | 41/45 | 0.03 |

| FIGO stage | I or II/III or IV | 91/51 | 36/20 | 55/31 | >0.99 |

| Tumor type | epidermal/others | 107/35 | 53/3 | 54/32 | <0.01 |

| Ascites | Yes/No | 79/63 | 30/26 | 49/37 | 0.73 |

| Residal tumor | Yes/No | 36/106 | 13/43 | 23/63 | 0.69 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | Yes/No | 97/45 | 46/10 | 51/35 | <0.01 |

| ASCT2 | Positive/Negative | 75/67 | 36/20 | 39/47 | 0.04 |

| CD98 | Positive/Negative | 56/86 | 43/13 | 13/73 | <0.01 |

| Ki-67 | High/Low | 71/71 | 35/21 | 36/50 | 0.03 |

| CD34 | High/Low | 62/80 | 31/25 | 31/55 | 0.03 |

Abbreviation: LAT1, L-type amino acid transportere 1; ASCT2, ASC-amino acid transporter 2; epidermal, epidermal ovarian. others; borderline malignancy, sex cord/stromal tumor, germ cell tumor and masodermal mixed tumor. FIGO, The International Federation.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the expression level of LAT1 among patients with epidermal ovarian cancers (n=107). Positive rate of LAT1 expression was observed in 50% of all cases (n=107), 37% of serous adenocarcinoma (n=30), 54% of endometrioid adenocarcinoma (n=26), 15% of mucinous adenocarcinoma (n=13), 75% of clear cell adenocarcinoma (n=32) and 33% of the other cancers (n=6). A statistically significant difference in the positive rate of LAT1 expression was recognized between clear cell adenocarcinoma and serous adenocarcinoma (P=0.004), and between serous adenocarcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma (P=0.037), but no statistically significant difference was observed between clear cell adenocarcinoma and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (P=0.105), and between serous adenocarcinoma and endometrioid adenocarcinoma (P=0.281).

In addition, we investigated whether the biomarkers such as LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98 could differentiate epidermal ovarian cancer from borderline malignancy. The positive rate (57% vs. 52%; P=0.668) and average score (2.1±1.1 vs. 2.1±1.1; P=0.993) for ASCT2 expression was not significantly different between ovarian cancer and borderline malignancy. However, the expression level of LAT1 and CD98 was identified as being significantly higher in ovarian cancer than borderline malignancy regarding both a positive rate (LAT1: 50% vs. 0%, P<0.001; CD98: 46% vs. 11%, P<0.001) and average scoring (LAT1: 2.0±1.2 vs. 1.0±0.0, P=0.004; CD98: 1.8±1.0 vs. 1.1±0.3, P<0.001). Especially, there was no evidence of LAT1 immunostaining in any patients with borderline malignancies. No residual tumor was defined as complete resection or no dissemination.

Correlations between the LAT1 expression and the different variables

In all patients (n=142), Spearman’s rank test revealed that the LAT1 expression was significantly correlated with the ASCT2 (r=0.223, P=0.008), CD98 (r=0.701, P<0.001), Ki-67 (r=0.169, P=0.047) and CD34 (r=0.234, P=0.006). In 107 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, LAT1 showed also a significant correlation with ASCT2 (r=0.222, P=0.019), CD98 (r=0.695, P<0.001), Ki-67 (r=0.041, P=0.998) and CD34 (r=0.231, P=0.015).

Univariate and multivariate survival analyses

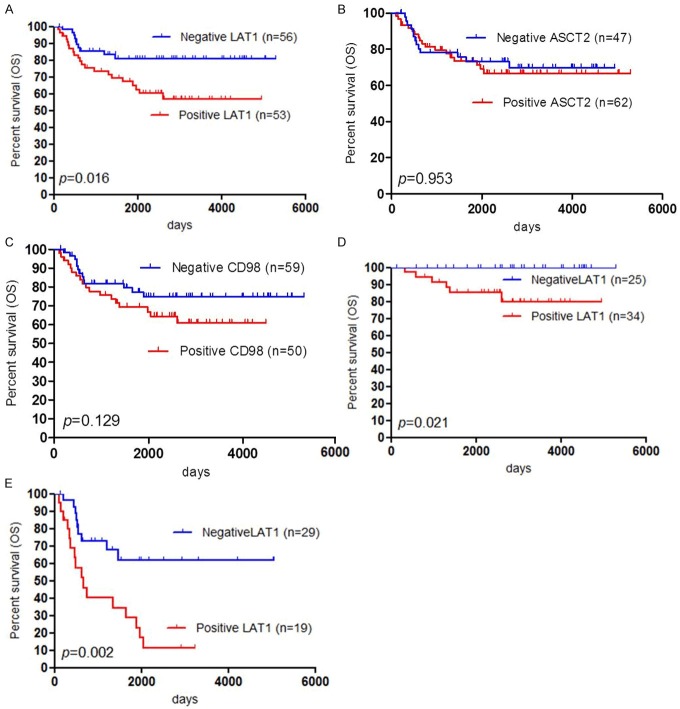

The five-year survival rates of PFS and OS for all patients (n=147) and patients with epidermal ovarian cancer (n=107) were 71% and 78%, respectively, and 64% and 74%, respectively. Out of the 107 patients with epidermal ovarian cancer, 30 died and 42 developed recurrence after the initial surgery. We performed the univariate and multivariate analyses for all patients (Table 2). By univariate analysis, we found that FIGO stage, tumor type, ascites, residual tumor, LAT1 expression and Ki-67 labelling index were identified to be significant variables for OS. Significant prognostic factors for PFS in the univariate analysis were almost the same as those for OS, identifying LAT1 expression to be not significant marker for PFS. The multivariate analysis confirmed that FIGO stage and a positive LAT1 expression were independent prognostic factors for predicting a negative OS, and a significant prognostic variable for PFS was only FIGO stage. Next, we performed the univariate and multivariate analyses for patients with epidermal ovarian cancer (Table 3). The univariate analysis indicated that FIGO stage, histology, ascites, residual tumor, LAT1 expression and Ki-67 labelling index were significant negative prognostic markers for OS and significant prognostic factors for PFS were almost the same as those for OS except for LAT1 expression. By the multivariate analysis, FIGO stage and a positive LAT1 expression were identified as significant independent prognostic factors to predict a poor OS, corresponding to the results of OS and PFS in all patients. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients with a positive and negative expression of LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate survival analysis in all patients (n=142)

| Variables | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 5-yrs rate (%) | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | 5-yrs rate (%) | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Age | ≤50/>50 yr | 86/73 | 0.051 | 80/64 | 0.031 | ||||||

| FIGO stage | I or II/III or IV | 94/44 | <0.001 | 4.84 | 2.14-20.66 | <0.001 | 85/38 | <0.001 | 2.43 | 1.51-4.16 | <0.001 |

| Tumor type | Ovarian cancers/Others | 74/94 | 0.01 | 1.16 | 0.62-2.96 | 0.672 | 64/91 | 0.012 | 1.26 | 0.81-2.18 | 0.334 |

| Ascites | Yes/No | 66/93 | <0.001 | 1.54 | 0.62-6.76 | 0.387 | 57/87 | <0.001 | 0.956 | 0.58-1.65 | 0.864 |

| Residal tumor | Yes/No | 45/86 | <0.001 | 0.85 | 0.56-1.27 | 0.434 | 38/78 | <0.001 | 1.03 | 0.71-1.47 | 0.868 |

| LAT1 | Positive/Negative | 64/87 | <0.001 | 2.13 | 1.45-3.22 | <0.001 | 63/76 | 0.122 | |||

| ASCT2 | Positive/Negative | 78/77 | 0.92 | 66/76 | 0.115 | ||||||

| CD98 | Positive/Negative | 70/83 | 0.02 | 65/74 | 0.205 | ||||||

| Ki-67 | High/Low | 65/91 | <0.001 | 57/85 | <0.001 | ||||||

| CD34 | High/Low | 76/81 | 0.132 | 64/76 | 0.121 | ||||||

Abbreviation: LAT1, L-type amino acid transporter 1; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate survival analysis in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (n=107)

| Variables | Overall survival | Disease-free survival | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 5-yrs rate (%) | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | 5-yrs rate (%) | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Age | ≤50/>50 yr | 75/72 | 0.42 | 67/63 | 0.54 | ||||||

| FIGO stage | I or II/III or IV | 91/45 | <0.001 | 5.2 | 2.23-22.29 | <0.001 | 79/35 | <0.001 | 2.2 | 1.32-3.59 | 0 |

| Histology | Serous/Other | 50/81 | 0.01 | 1.6 | 0.96-2.61 | 0.0 | 38/72 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 0.82-1.85 | 0.3 |

| Ascites | Yes/No | 65/89 | 0.01 | 1.7 | 0.67-7.36 | 0.3 | 54/81 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.53-1.58 | 0.7 |

| Residal tumor | Yes/No | 43/83 | <0.001 | 1.6 | 0.98-2.83 | 0.06 | 35/73 | <0.001 | 0.9 | 0.57-1.33 | 0.6 |

| LAT1 | Positive/Negative | 66/82 | 0.02 | 5 | 2.21-12.26 | <0.001 | 63/65 | 0.6 | |||

| ASCT2 | Positive/Negative | 73/71 | 0.95 | 58/72 | 0.15 | ||||||

| CD98 | Positive/Negative | 69/76 | 0.13 | 63/66 | 0.49 | ||||||

| Ki-67 | High/Low | 65/86 | 0.02 | 53/79 | 0.01 | ||||||

| CD34 | High/Low | 74/73 | 0.44 | 59/66 | 0.42 | ||||||

Abbreviation: LAT1, L-type amino acid transporter 1; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3.

Outcome after surgical resection given by Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) according to LAT1, ASCT2 and CD98 expression. A statistically significant difference in OS was observed between patients with positive and negative LAT1 expression (A). There was not statistically different between patients with positive and negative ASCT2 expression (B), and between patients with positive and negative CD98 expression (C). Survival analysis according to FIGO staging (early or advanced stage) showed that patients with a positive LAT1 expression achieved worse prognosis in stage I/II (D) and stage III/IV (E) than those with negative LAT1 expression.

Finally, we performed a survival analysis with respect to the expression of LAT1 in epidermal ovarian cancer (n=107) according to FIGO staging (stage I/II or stage III/IV) (Table 4). A positive LAT1 expression was proven to be a significant prognostic factor for predicting a poor OS in stage I/II (Figure 3D) and stage III/IV (Figure 3E).

Table 4.

Patient’s demographics according to LAT1 expression in epithelial ovarian cancer (N=107)

| Variables | Total (n=107) | LAT1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Positive (n=53) | Negative (n=54) | p-value | |||

| Age | ≤50/>50 yr | 36/71 | 14/39 | 22/32 | 0.15 |

| FIGO stage | I or II/III or IV | 59/48 | 34/19 | 25/29 | 0.08 |

| Histology | Serous/Other | 30/77 | 11/42 | 19/35 | 0.13 |

| Ascites | Yes/No | 70/37 | 29/24 | 41/13 | 0.03 |

| Residal tumor | Yes/No | 34/73 | 13/40 | 21/33 | 0.15 |

| Grade | 1 or 2/3 | 28/30 | 13/10 | 15/20 | 0.42 |

| NA | 51 | 30 | 19 | - | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | Yes/No | 87/20 | 44/9 | 43/10 | >0.99 |

| ASCT2 | Positive/Negative | 61/46 | 34/19 | 27/27 | 0.17 |

| CD98 | Positive/Negative | 49/51 | 40/13 | 9/45 | <0.01 |

| Ki-67 | High/Low | 61/46 | 32/21 | 29/25 | 0.56 |

| CD34 | High/Low | 51/57 | 29/24 | 22/33 | 0.17 |

Abbreviation: LAT1, L-type amino acid transportere 1; ASCT2, ASC-amino acid transporter 2; serous, serous adenocarcinoma; cancers including mucinous adenocarcinoma, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma, undifferentiated malignant Brenner tumor; FIGO, The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Others, ovarian carcinoma.

Discussion

This is a first clinicopathological study to examine the clinical significance of amino acid transporters (LAT1 and ASCT2) in patients with ovarian tumors. LAT1 and ASCT2 were highly expressed in ovarian tumors, especially epidermal ovarian cancer. A positive LAT1 expression was closely correlated with the expression for ASCT2 and CD98, and cell proliferation (Ki-67) in ovarian cancer. Our study disclosed that LAT1 was clarified as a significant independent marker for predicting a poor OS and could clearly discriminate between epidermal ovarian cancer and borderline malignancy. The expression level of LAT1 within ovarian cancer cells varied among SA, EA, CCA and MA, and we found LAT1 expression was higher in CCA than other histological types. Our study suggests that LAT1 expression plays a crucial role in the malignant formation and tumor progression in ovarian cancer.

Recent studies have clarified that LAT1 is highly expressed in various human cancers and proves to be closely associated with tumor progression and metastases [4,5,8-14]. Based on a broad spectrum of data From recent, we have known data about the frequency of LAT1 expression among human cancers. LAT1 expression in adenocarcinoma has been described to be closely associated with prognosis [4,5,8-15]. LAT1 expression is identified as a significant independent predictor relating with poor outcome for patients such as pulmonary adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, hepatobiliary cancer, gastric cancer and prostatic cancer [4-14]. In these neoplasms, LAT1 also has been proven to be closely related to tumor cell proliferation, angiogenesis and metastases, having a covalent association with the heavy chain of 4F2hc/CD98 [3,16]. In the present study, LAT1 seemed to play an important role in the tumor growth and survival of ovarian cancer. Interestingly, LAT1 might be helpful in differentiating borderline malignancyand ovarian cancer. Of 107 patients with epidermal ovarian cancer, the expression level of LAT1 in clear cell adenocarcinoma was prominently higher compared to the other histological types. Recently, Kaji et al have described that LAT1 plays a significant role in nutrition, proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer and is significantly up-regulated in various human epithelial ovarian cancers [17]. Large-scale study is warranted to confirm the results of our investigation according to the detailed analyses of each histological type in epithelial ovarian cancer.

In in vitro studies, it has been reported that LAT1 expression is increased in human ovarian cancer cell lines and the inhibition of LAT1 suppressed the proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer cells [18]. 2-aminobicyclo-(2,2,1)-heptane-2-carboxylic acid (BCH) was used as an inhibitor of LAT1 in those studies [18]. We also had investigated the targeting therapy for LAT1 in lung cancer and cholangiocarcinoma cells using BCH, and the in vitro and in vivo preliminary experiments disclosed that the inhibition of LAT1 by BCH significantly suppressed growth of the tumor and achieved an additive therapeutic efficacy [13]. LAT1 may be a promising molecular target for the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer.

In our study, the expression of ASCT2 was not identified as a significant prognostic variable for predicting a worse outcome in human ovarian tumors. Although ASCT2 is highly expressed in ovarian tumors, it was not useful to differentiate between borderline and malignant tumors. In previous studies, ASCT2 is highly expressed in various types of cancer cells that require glutamine for their survival and growth [6,7,14,15,19]. LAT1 provides the essential amino acids that signal to enhance tumor cell growth via the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, and ASCT2 keeps the cytoplasmic amino acid pool necessary to drive LAT1 function and fuel energy via delivery of glutamine [5]. Thus, the expression levels of LAT1 and ASCT2 are coordinately rose in human cancer and these two obligate amino acid exchangers are closely associated with the cell growth and survival linked to the mTOR signaling pathway [5]. Recent review has described that the mTOR pathway is frequently activated in ovarian cancer, especially clear cell carcinoma and endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and has a potential of therapeutic target for treatment of ovarian cancer [11,19]. In several human cancers, both the expression of LAT1 and ASCT2 showed a significant relationship with the phosphorylation of mTOR signaling pathway [11,20]. In the present study, we couldn’t elucidate the coordinate role of LAT1 and ASCT2 and the relationship between these amino acid transporters and mTOR signaling pathway in ovarian cancer, but, future investigation is to disclose the clinicopathological significance of relationship between AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and the expression of amino acid transport complex consisting of LAT1, ASCT2, CD98 and CD147 in patients with ovarian cancer.

Limitation of our study must be addressed. One limitation is that the sample size of our study was small and the subgroup analysis may bias our results. Another limitation is that we analyzed the heterogeneity of ovarian tumors consisting of epidermal ovarian cancer, borderline malignancy, sex/cord stromal tumor and germ cell tumor. LAT1 expression was proven to be variable according to histological type of cancers. Future study must focus on the individual population using immunohistochemistry.

In conclusion, we found that LAT1 is highly expressed in various ovarian tumors and a positive LAT1 expression can serve as a significant independent factor for predicting a poor OS in patients with ovarian cancer. As a differentiated diagnosis, the immunostaining of LAT1 successfully could distinguish between borderline and malignant tumors. LAT1 is closely correlated with the expression of CD98 and ASCT2, and cell proliferation by Ki-67 labelling index. Inhibition of LAT1 has a potential of attractive molecular target for epidermal ovarian cancer in the future.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by advanced research for medical products Mining Programme of the National Institute of Biomedical Innovation (NIBIO). We also deeply appreciate Prof. Masahiko Nishiyama of Department of Molecular Pharmacology, Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine, for the critical review of this manuscript, Ms. Yuka Matsui for her technical assistance of manuscript submission and Ms. Tomoko Okada for her data collection and technical assistance.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. Ca Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanai Y, Segawa H, Miyamoto KI, Uchino H, Takeda E, Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23629–232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanagida O, Kanai Y, Chairoungdua A, Kim DK, Segawa H, Nii T, Cha SH, Matsuo H, Fukushima J, Fukasawa Y, Tani Y, Taketani Y, Uchino H, Kim JY, Inatomi J, Okayasu I, Miyamoto K, Takeda E, Goya T, Endou H. Human L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT 1): characterization of function and expression in tumor cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1514:291–302. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Hisada T, Tanaka S, Ishizuka T, Kanai Y, Endou H, Nakajima T, Mori M. Prognostic significance of L-type amino acid transporter 1 expression in resectable stage I-III nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:742–748. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs BC, Bode BP. Amino acid transporters ASCT2 and LAT1 in cancer: Partners in crime? Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;15:254–66. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li R, Younes M, Frolov A, Wheeler TM, Scardino P, Ohori M, Ayala G. Expression of neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human prostate. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witte D, Ali N, Carlson N, Younes M. Overexpression of the neutral amino acid transporter ASCT2 in human colorectal adenocarcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:2555–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakata T, Ferdous G, Tsuruta T, Satoh T, Baba S, Muto T, Ueno A, Kanai Y, Endou H, Okayasu I. L-type amino acid transporter 1 as a novel biomarker for high-grade malignancy in prostate cancer. Pathol Int. 2009;59:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichinoe M, Mikami T, Yoshida T, Igawa I, Tsuruta T, Nakada N, Anzai N, Suzuki Y, Endou H, Okayasu I. High expression of L-type amino-acid transporter 1 (LAT1) in gastric carcinomas: Comparison with non-cancerous lesions. Pathol Int. 2011;61:281–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furuya M, Horiguchi J, Nakajima H, Kanai Y, Oyama T. Correlation of L-type amino acid transporter 1 and CD98 expression with triple negative breast cancer prognosis. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:382–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Takahashi T, Nakagawa K, Ohde Y, Okumura T, Murakami H, Shukuya T, Kenmotsu H, Naito T, Kanai Y, Endo M, Kondo H, Nakajima T, Yamamoto N. LAT1 expression is closely associated with hypoxic markers and mTOR in resected non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2011;3:468–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaira K, Sunose Y, Arakawa K, Ogawa T, Sunaga N, Shimizu K, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Itoh H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Segawa A, Furuya M, Mori M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. Prognostic significance of L-type amino-acid transporter 1 expression in surgically resected pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:632–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaira K, Sunose Y, Ohshima Y, Ishioka NS, Arakawa K, Ogawa T, Sunaga N, Shimizu K, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Itoh H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Yamaguchi A, Segawa A, Ide M, Mori M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. Clinical significance of L-type Amino Acid Transporter 1 Expression as a Prognostic marker and Potential of New Targeting Therapy in Biliary Tract Cancer. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namikawa M, Kakizaki S, Kaira K, Tojima H, Yamazaki Y, Horiguchi N, Sato K, Oriuchi N, Tominaga H, Sunose Y, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I, Yamada M. Expression of amino acid transporters (LAT1, ASCT2 and xCT) as clinical significance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hepr.12431. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyoda M, Kaira K, Ohshima Y, Ishioka NS, Shino M, Sakakura K, Takayasu Y, Takahashi K, Tominaga H, Oriuchi N, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Oyama T, Chikamatsu K. Prognostic significance of amino-acid transporter expression (LAT1, ASCT2 and xCT) in surgically resected tongue cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2506–13. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaira K, Oriuchi N, Imai H, Shimizu K, Yanagitani N, Sunaga N, Hisada T, Tanaka S, Ishizuka T, Kanai Y, Endou H, Nakajima T, Mori M. L-type amino acid transporter 1 and CD98 expression in primary and metastatic sites of human neoplasms. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2380–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaji M, Kabir-Salmani M, Anzai N, Jin CJ, Akimoto Y, Horita A, Sakamoto A, Kanai Y, Sakurai H, Iwashita M. Properties of L-type amino acid transporter 1 in epidermal ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:329–36. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d28e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan X, Ross DD, Arakawa H, Ganapathy V, Tamai I, Nakanishi T. Impact of system L amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) on proliferation of human ovarian cancer cells: a possible target for combination therapy with anti-proliferative aminopeptidase inhibitors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:811–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimizu K, Kaira K, Tomizawa Y, Sunaga N, Kawashima O, Oriuchi N, Tominaga H, Nagamori S, Kanai Y, Yamada M, Oyama T, Takeyoshi I. ASC amino-acid transporter 2 (ASCT2) as a novel prognostic marker in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2030–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mabuchi S, Kuroda H, Takahashi R, Sasano T. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:173–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]