Abstract

Background. Neck circumference (NC) is an anthropometric measure of obesity for upper subcutaneous adipose tissue distribution which is associated with cardiometabolic risk. This study investigated whether NC is associated with indicators of chronic kidney disease (CKD) for high cardiometabolic risk patients. Methods. A total of 177 consecutive patients who underwent the outpatient departments of cardiology were prospectively enrolled in the study. The patients were aged >20 years with normal renal function or with stages 1–4 CKD. A linear regression was performed using the Enter method to present an unadjusted R 2, standardized coefficients, and standard error, and the Durbin-Watson test was used to assess residual independence. Results. Most anthropometric measurements from patients aged ≧65 were lower than those from patients aged <65, except for women's waist circumference (WC) and waist hip ratio. Female NC obtained the highest R 2 values for 24 hr CCR, uric acid, microalbuminuria, hsCRP, triglycerides, and HDL compared to BMI, WC, and hip circumference. The significances of female NC with 24 hr CCR and uric acid were improved after adjusted age and serum creatinine. Conclusions. NC is associated with indicators of CKD for high cardiometabolic risk patients and can be routinely measured as easy as WC in the future.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are two important global public health concerns that share common cardiometabolic risk factors that include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia. The above three diseases generally coexist, making them the most common risk factors for CVD [1]. In 2007, the Taiwan Health Promotion Administration of the Ministry of Health and Welfare conducted a survey involving 5,895 healthy individuals in Taiwan and concluded that, among those patients with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, their rates of developing heart disease in 5 years are 1.9, 1.5, and 1.8 times greater than those without hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, respectively [2]. Cardiovascular events include fatal and nonfatal cardiovascular events (stroke, infarction, angina, and heart failure). Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia contribute to the increased risk of experiencing cardiovascular events [3]. It is suggested that patients who currently have CVD or have received coronary revascularization should take steps to mitigate their cardiovascular risks [4].

Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia are also initiation factors for CKD [5]. One study showed that mild renal insufficiency was common among community-based citizens and that this condition was related to the high prevalence of CVD. Mild renal insufficiency increases the risk of cardiovascular events and total mortality [6]. It was reported that a lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) correlates with a higher risk of cardiovascular events and the related death [7]. Microvascular abnormality is a common triggering factor for both CVD and CKD [8]. The Kidney Early Evaluation Program study suggested that conditions for cardiovascular risk are defined as a urine albumin: creatinine ratio ≥30 mg/g (3.4 mg/mmol) or an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 [7].

The main complication of CKD is CVD. Observations made in the Kidney Early Evaluation Program and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey studies suggested that CKD may increase the prevalence of myocardial infarction or stroke [8]. Medium to severe renal function impairments exacerbate atherosclerosis, which in turn leads to an increased risk of cardiovascular events [9]. This means the deaths of CKD patients are more likely caused by CVD than by progression of kidney failure [10]. However, patients with CVD also suffer from a higher risk of CKD [11]. Patients who have undergone coronary revascularization must be aware of their potential CKD risk for the future. That CKD may also cause atherosclerosis in coronary arteries and the cerebrovascular and peripheral circulatory system [12]. Additionally, the coexistence of CVD and CKD leads to higher mortality [6]. Therefore, CVD and CKD should be considered mutual risk factors for each other. Among CVD patients the CKD prevention is necessary, and similar condition is conversely alike. Therefore, development of an indicator that predicts the risk of both conditions would help to effectively treat the coexistence of both diseases.

Abdominal obesity and general obesity would cause increases in triglycerides, low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, blood sugar, insulin, and blood pressures. They will also cause decreases in high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. All of these factors may lead to onset of CVD, which in turn increases coronary heart disease onset or mortality and total mortality [13, 14]. Neck circumference (NC) is an indicator of upper body fat distribution, whereas body morphologies and fat distribution can be used as factors to assess the risk of obesity [15]. In addition to body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, and hip circumference measurements as indicators of obesity, NC can also be used as a novel indicator for cardiometabolic risk [16, 17]. However, previous studies have not focused on NC with CKD. This pilot study aimed to investigate the relationship between NC and CKD. We intend to confirm whether NC is as an associated indicator of CKD for high cardiovascular risk patients or whether it is as an alternative option for disabled or bedbound patients for whom other body anthropometric indicator measurements are not suitable.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework and Participants

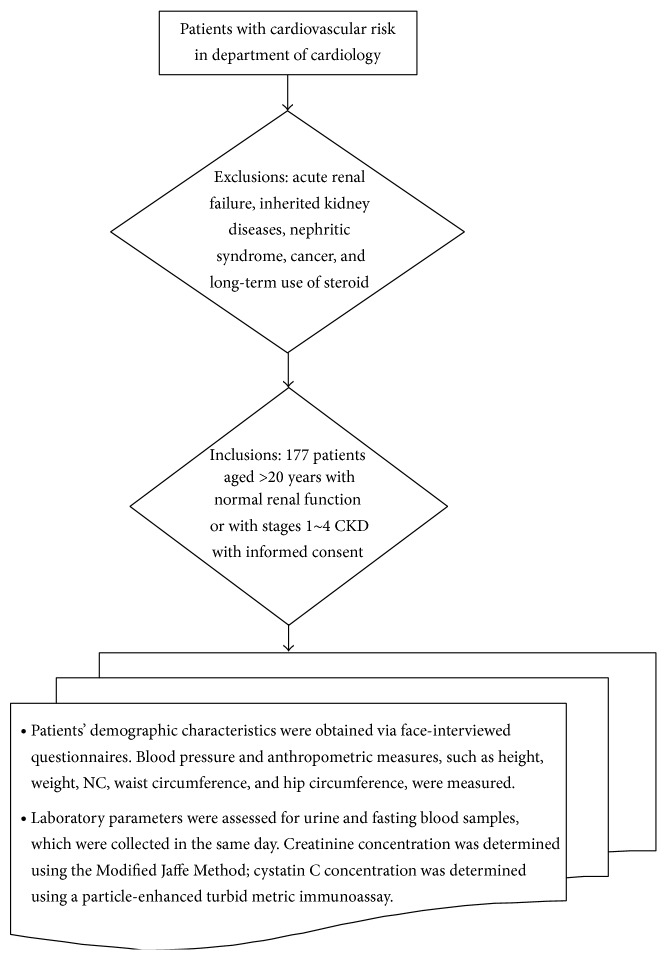

This study, as given in Figure 1, involved 177 patients with cardiovascular risk. Inclusion criteria were patients aged >20 years with normal renal function or with stages 1~4 CKD, excluding conditions such as acute renal failure, inherited kidney diseases, nephritic syndrome, cancer, and long-term use of steroid. This study was approved by the Institute Review Committees at Tri-Service General Hospital and Chiayi Chang Gung Memorial Hospital and all the participants signed informed consent prior to study enrolment.

Figure 1.

Research framework and participants.

2.2. Data Collection

Patients' demographic characteristics were obtained via face-interviewed questionnaires. Blood pressure and anthropometric measures, such as height, weight, NC, waist circumference, and hip circumference, were measured. Laboratory parameters were assessed for urine and fasting blood samples, which were collected in the same day. Creatinine concentration was determined using the Modified Jaffe Method with a SYNCHRON LXI 725 (Tokyo, Japan) instrument; cystatin C concentration was determined using a particle-enhanced turbid metric immunoassay with a Hitachi 7170 (Tokyo, Japan) instrument.

2.3. Assessment of Renal Function

GFR was calculated based on the 24-hour urine creatinine clearance rate (24 hr CCR) to assess renal function. The equation for 24 hr CCR is as follows: (24 hr urine total volume × urine creatinine concentration)/(creatinine concentration × 1440). The eGFR calculation was based on Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD), as eGFRMDRD = 186 × crea−1.154 × age−0.203 × (0.742 if female) × (1.212 if black), and Cockcroft-Gault Equation (CG), as eGFRCG = [(140 − age) × weight (kg)] ÷ (creatinine (mg/dL) × 72) × (0.85 if female).

2.4. Data Processing

All data were grouped by gender or age. A t-test was performed to assess the differences between ages within the same gender groups. The relevance between NC and each laboratory measurement was assessed using the Spearman correlation analysis. Continuous data for males and females were analyzed separately using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or the Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution. If data were not normally distributed, logarithmic transformation of the data was performed to make the data fit a normal distribution. To investigate the relevance between anthropometric measures and heart disease and CKD risk factors, a linear regression was performed using the Enter method to present an unadjusted R 2, standardized coefficients, and standard error, and the Durbin-Watson test was used to assess residual independence. An age adjustment was made for all assessed cardiovascular risk factors. To avoid the impact of renal function differences in individuals, age and log(creatinine) were included to correct the risk factors assessment. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant level.

3. Results

The characteristics of 177 participants in this study are presented in Table 1. There were 122 (71%) males with a mean age of 66 and 50 (29%) females with a mean age of 67. For most anthropometric measures, the measurements from patients ≧ 65 years old were lower than those from patients < 65 years old, except for women's waist circumference and waist hip ratio. Differences were observed in weight, BMI, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, serum creatinine, cystatin C, phosphorus, 24 hr CCR, eGFRMDRD, and eGFRCG between different ages among males. In each age of females, the differences were observed in height, weight, BMI, hip circumference, waist hip ratio, NC, cystatin C, albumin, urine creatinine, 24 hr CCR, and eGFRCG. Elderly patients of both genders typically perform a poor renal function.

Table 1.

Study characteristics by sex and age.

| Variables, mean (SD) | Men, n = 125 | Women, n = 52 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <65 yrs (n = 57) | ≧65 yrs (n = 68) | P value | <65 yrs (n = 26) | ≧65 yrs (n = 26) | P value | |

| Age (yrs) | 58 (5.2) | 73.7 (5.3) | <0.001 | 58.6 (5.5) | 75.1 (6) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 166.2 (6.1) | 164.8 (4.8) | 0.166 | 157 (5.7) | 153 (5.8) | 0.015 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.8 (11.8) | 70.8 (10.4) | 0.003 | 68.9 (12) | 59.7 (8.6) | 0.002 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.7 (3.5) | 26 (3.7) | 0.011 | 27.9 (4) | 25.5 (3) | 0.017 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 97.3 (9.7) | 94.5 (9.3) | 0.104 | 92.3 (11.3) | 95.8 (9.2) | 0.230 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 101.8 (7.2) | 100.2 (7.2) | 0.224 | 102.3 (10.4) | 97.5 (5.9) | 0.049 |

| Waist hip ratio | 1 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.198 | 0.9 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Neck circumference (cm) | 40.6 (3.3) | 39.6 (3.3) | 0.100 | 36.6 (2.9) | 34.7 (2.6) | 0.017 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 137.3 (12.3) | 136.4 (16.1) | 0.732 | 132.1 (12) | 133.9 (11.7) | 0.588 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.9 (6.7) | 76.8 (8.9) | 0.030 | 78 (8) | 73.9 (8.3) | 0.073 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 119.5 (44.2) | 110.9 (27) | 0.205 | 111.3 (30.5) | 112.5 (27.6) | 0.883 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 183.2 (34.5) | 181.2 (32.2) | 0.748 | 205.6 (41.1) | 197.8 (29.4) | 0.448 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 114.5 (29.9) | 114.5 (27.1) | 0.990 | 123.5 (37.1) | 112.9 (27.4) | 0.258 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44.3 (7.8) | 46.5 (15.4) | 0.315 | 53.9 (12.9) | 49.9 (11.3) | 0.258 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 148.5 (74.4) | 117.1 (46.9) | 0.006 | 137.9 (80.1) | 136.3 (53.4) | 0.937 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.5) | 0.011 | 0.9 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0.584 |

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.4) | <0.001 | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.024 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 17.9 (6.3) | 20.2 (7.2) | 0.075 | 16.9 (4.8) | 18.9 (10.1) | 0.373 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 7 (1.6) | 6.9 (1.4) | 0.908 | 6 (1.6) | 6.2 (1.5) | 0.632 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.4 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.3) | 0.437 | 4.4 (0.3) | 4.3 (0.2) | 0.046 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 2 (2) | 1.6 (2.2) | 0.319 | 2.1 (2.5) | 2.1 (2.7) | 0.992 |

| Microalbuminuria (mg/day) | 23.4 (33) | 29.5 (61.1) | 0.505 | 29.2 (54.8) | 17.6 (34.6) | 0.377 |

| Total protein (mg/dL) | 7.4 (0.5) | 7.6 (0.5) | 0.094 | 7.7 (0.5) | 7.5 (0.4) | 0.138 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 28.9 (23.1) | 30.7 (30.2) | 0.721 | 25.4 (10.6) | 26.3 (20.3) | 0.842 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 35.7 (31.2) | 33.8 (37.4) | 0.753 | 35.7 (30.9) | 23 (18.7) | 0.085 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 63.6 (24.4) | 61.4 (15.1) | 0.777 | 65.7 (15.1) | 64 (33.1) | 0.912 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.8 (0.5) | 8.7 (0.5) | 0.655 | 8.7 (0.5) | 8.8 (0.7) | 0.547 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 3.5 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.5) | 0.012 | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.7 (0.5) | 0.175 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 143.7 (2) | 143.2 (2.2) | 0.200 | 144.4 (2) | 143.8 (2) | 0.299 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.9 (5.3) | 4.9 (5.4) | 0.953 | 5.8 (8.1) | 6.4 (9.1) | 0.842 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.1 (1.4) | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.233 | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.194 |

| Urine creatinine (mg/dL) | 74.6 (28.7) | 79.7 (36.2) | 0.395 | 71.9 (30.9) | 56.1 (17.9) | 0.034 |

| 24 hr CCR (mL/min) | 103.3 (33.1) | 78.1 (31.7) | <0.001 | 93 (33.3) | 67.8 (25.9) | 0.004 |

| eGFRMDRD (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 75.1 (18.9) | 62.1 (17.5) | <0.001 | 72.6 (20) | 67 (19) | 0.319 |

| eGFRCG (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 81.7 (23.6) | 53.7 (16.5) | <0.001 | 76.8 (23.8) | 52 (15.2) | <0.001 |

Table 2 showed the Spearman correlation coefficients with NC between both sexes. In males, most relevant coefficients were significant, especially those anthropometric measures, fasting glucose, triglycerides, cystatin C, aspartate aminotransferase, 24 hr CCR, and eGFRCG, where positive correlations were observed between NC and 24 hr CCR, eGFRCG, hsCRP, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol. In females, diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, uric acid, albumin, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), total protein, phosphorus, and eGFRCG reached significance, where negative correlations were observed between NC and total cholesterol, HDL, total protein, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, phosphorus, sodium, and potassium.

Table 2.

Spearman correlation coefficients of neck circumference by sex and age.

| Variables | Men < 65 yrs (n = 57) | Men ≧ 65 yrs (n = 68) | Women < 65 yrs (n = 26) | Women ≧ 65 yrs (n = 26) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | P value | Coefficients | P value | Coefficients | P value | Coefficients | P value | |

| Age (yrs) | −0.263 | 0.048 | −0.113 | 0.361 | −0.373 | 0.060 | 0.167 | 0.414 |

| Height (cm) | 0.125 | 0.355 | 0.149 | 0.224 | 0.552 | 0.003 | 0.255 | 0.209 |

| Weight (kg) | 0.677 | <0.001 | 0.649 | <0.001 | 0.635 | <0.001 | 0.760 | <0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 0.738 | <0.001 | 0.643 | <0.001 | 0.417 | 0.034 | 0.668 | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 0.665 | <0.001 | 0.712 | <0.001 | 0.331 | 0.098 | 0.622 | 0.001 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 0.660 | <0.001 | 0.743 | <0.001 | 0.560 | 0.003 | 0.832 | <0.001 |

| Waist hip ratio | 0.342 | 0.009 | 0.337 | 0.005 | −0.054 | 0.794 | 0.114 | 0.579 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.059 | 0.665 | 0.230 | 0.059 | 0.159 | 0.438 | 0.185 | 0.365 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 0.141 | 0.295 | 0.229 | 0.060 | 0.648 | <0.001 | −0.170 | 0.406 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 0.125 | 0.356 | 0.339 | 0.006 | −0.027 | 0.899 | 0.092 | 0.662 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.222 | 0.097 | 0.104 | 0.409 | −0.170 | 0.418 | −0.032 | 0.879 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.227 | 0.089 | 0.223 | 0.074 | −0.229 | 0.271 | 0.193 | 0.356 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 0.099 | 0.464 | −0.181 | 0.156 | −0.274 | 0.185 | −0.261 | 0.218 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 0.176 | 0.191 | 0.339 | 0.006 | 0.295 | 0.152 | 0.423 | 0.044 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | −0.167 | 0.215 | −0.076 | 0.546 | 0.057 | 0.788 | −0.036 | 0.866 |

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 0.303 | 0.034 | −0.100 | 0.450 | 0.276 | 0.226 | −0.041 | 0.863 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | −0.040 | 0.773 | 0.116 | 0.377 | −0.090 | 0.668 | 0.318 | 0.121 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | −0.202 | 0.135 | 0.113 | 0.374 | 0.630 | 0.001 | 0.140 | 0.505 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 0.057 | 0.674 | 0.082 | 0.521 | 0.268 | 0.195 | −0.397 | 0.050 |

| hsCRP (mg/L) | 0.188 | 0.174 | 0.244 | 0.058 | 0.627 | 0.001 | 0.053 | 0.806 |

| Microalbuminuria (mg/day) | 0.238 | 0.077 | 0.049 | 0.709 | 0.380 | 0.067 | 0.256 | 0.217 |

| Total protein (mg/dL) | 0.044 | 0.745 | 0.078 | 0.541 | −0.040 | 0.849 | −0.607 | 0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 0.003 | 0.982 | −0.314 | 0.012 | −0.011 | 0.957 | −0.161 | 0.443 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 0.028 | 0.834 | 0.089 | 0.482 | −0.020 | 0.925 | −0.044 | 0.833 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 0.443 | 0.172 | 0.185 | 0.526 | −0.319 | 0.538 | 0.559 | 0.192 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | −0.018 | 0.895 | 0.157 | 0.215 | 0.260 | 0.209 | 0.171 | 0.414 |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | −0.121 | 0.373 | −0.013 | 0.918 | −0.221 | 0.288 | −0.432 | 0.031 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 0.070 | 0.606 | 0.117 | 0.357 | −0.134 | 0.524 | −0.237 | 0.255 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 0.001 | 0.995 | 0.261 | 0.067 | −0.055 | 0.818 | −0.026 | 0.915 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.001 | 0.997 | −0.041 | 0.746 | 0.277 | 0.180 | −0.116 | 0.581 |

| Urine creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.165 | 0.220 | 0.037 | 0.770 | 0.249 | 0.230 | −0.011 | 0.958 |

| 24 hr CCR (mL/min) | 0.440 | 0.001 | 0.296 | 0.017 | 0.231 | 0.267 | 0.064 | 0.760 |

| eGFRMDRD (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.216 | 0.107 | 0.077 | 0.541 | −0.066 | 0.752 | 0.039 | 0.852 |

| eGFRCG (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.475 | <0.001 | 0.355 | 0.004 | 0.341 | 0.095 | 0.442 | 0.027 |

Regression curves after age adjustment are shown in Table 3(a). Compared to BMI, waist circumference, and hip circumference, the higher R 2 values were obtained for female NC and microalbuminuria, hsCRP, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol. Age- and log(creatinine)-adjusted curves are shown in Table 3(b). The items showing statistical significance in male and female NC are roughly the same as those in Table 3(a). Female NC was adjusted for age and log(creatinine), the significance of 24 hr CCR and uric acid was improved. Compared to BMI, waist circumference, and hip circumference, the highest R 2 values were obtained for female NC and 24 hr CCR, uric acid, microalbuminuria, hsCRP, triglycerides, and HDL cholesterol (negative correlation).

Table 3.

(a) Age adjusted linear regression of CVD and CKD risk among body shape indicators. (b) Age- and log(creatinine)-adjusted linear regression of CVD and CKD risk among body shape indicators.

(a).

| Dependent variables | Men (n = 125) | Women (n = 52) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | R 2 | B (SE) | P value | R 2 | B (SE) | P value |

| 24 hr CCR | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.279 | 269.32 (76.68) | 0.001 | 0.232 | 114.479 (122.29) | 0.243 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.290 | 181.14 (47.90) | <0.001 | 0.211 | −26.755 (73.81) | 0.719 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.310 | 268.82 (62.92) | <0.001 | 0.210 | −13.095 (87.87) | 0.882 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.337 | 412.97 (84.67) | <0.001 | 0.210 | −30.973 (117.5) | 0.793 |

| eGFRCG | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.524 | 206.02 (44.09) | <0.001 | 0.503 | 163.779 (71.69) | 0.027 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.591 | 172.49 (25.72) | <0.001 | 0.534 | 121.746 (41.36) | 0.005 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.601 | 237.27 (33.85) | <0.001 | 0.531 | 142.509 (49.32) | 0.006 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.588 | 312.44 (47.22) | <0.001 | 0.576 | 236.87 (62.72) | <0.001 |

| eGFRMDRD | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.140 | 20.87 (46.60) | 0.655 | 0.081 | −50.119 (81.36) | 0.541 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.144 | 25.1 (29.26) | 0.393 | 0.130 | −82.537 (47.14) | 0.086 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.150 | 49.83 (38.86) | 0.202 | 0.084 | −42.682 (57.52) | 0.462 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.157 | 85.06 (53.13) | 0.112 | 0.096 | −82.797 (76.46) | 0.284 |

| log(Cystatin C) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.179 | 0.43 (0.31) | 0.166 | 0.210 | 0.131 (0.49) | 0.789 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.166 | −0.09 (0.19) | 0.624 | 0.313 | 0.635 (0.26) | 0.021 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.166 | 0.15 (0.26) | 0.571 | 0.263 | 0.543 (0.33) | 0.104 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.169 | 0.29 (0.36) | 0.419 | 0.254 | 0.634 (0.42) | 0.139 |

| Uric Acid | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.009 | −3.75 (3.99) | 0.349 | 0.188 | 19.258 (6.05) | 0.003 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.002 | 0.02 (2.45) | 0.993 | 0.216 | 12.354 (3.54) | 0.001 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.002 | −0.41 (3.28) | 0.901 | 0.111 | 10.223 (4.48) | 0.027 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.014 | −5.39 (4.48) | 0.231 | 0.149 | 16.098 (5.87) | 0.009 |

| log(Urine microalbuminuria) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.021 | 2.36 (1.51) | 0.120 | 0.200 | 7.255 (2.16) | 0.002 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.093 | 3.14 (0.92) | 0.001 | 0.105 | 3.089 (1.35) | 0.027 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.058 | 3.26 (1.23) | 0.009 | 0.110 | 3.764 (1.6) | 0.023 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.049 | 4.09 (1.70) | 0.017 | 0.06 | 3.661 (2.19) | 0.102 |

| log(hsCRP) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.048 | 2.98 (1.40) | 0.036 | 0.101 | 4.366 (1.96) | 0.031 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.062 | 2.13 (0.85) | 0.014 | 0.067 | 2.091 (1.18) | 0.084 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.055 | 2.66 (1.14) | 0.022 | 0.063 | 2.407 (1.41) | 0.094 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.043 | 3.15 (1.59) | 0.049 | 0.095 | 3.995 (1.86) | 0.037 |

| log(Systolic blood pressure) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.015 | 0.14 (0.12) | 0.252 | 0.025 | 0.175 (0.16) | 0.292 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.042 | 0.16 (0.07) | 0.031 | 0.003 | −0.006 (0.1) | 0.951 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.031 | 0.18 (0.10) | 0.068 | 0.006 | 0.049 (0.12) | 0.674 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.036 | 0.27 (0.14) | 0.047 | 0.006 | 0.061 (0.16) | 0.698 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.105 | 27.44 (19.94) | 0.171 | 0.260 | 31.523 (30.9) | 0.313 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.157 | 37.4 (12.09) | 0.002 | 0.045 | −4.045 (18.69) | 0.830 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.114 | 29.63 (16.58) | 0.076 | 0.273 | 29.645 (21.42) | 0.173 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.123 | 48.09 (22.66) | 0.036 | 0.260 | 29.157 (29.33) | 0.325 |

| log(Fasting plasma glucose) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.023 | 0.48 (0.29) | 0.100 | 0.013 | 0.142 (0.41) | 0.731 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.055 | 0.47 (0.18) | 0.010 | 0.022 | 0.176 (0.24) | 0.474 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.094 | 0.82 (0.23) | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.165 (0.29) | 0.573 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.034 | 0.68 (0.33) | 0.042 | 0.016 | −0.19 (0.39) | 0.627 |

| log(Triglyceride) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.137 | 1.49 (0.46) | 0.002 | 0.172 | 2.45 (0.82) | 0.005 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.089 | 0.56 (0.30) | 0.064 | 0.145 | 1.379 (0.51) | 0.010 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.087 | 0.73 (0.40) | 0.070 | 0.138 | 1.562 (0.6) | 0.012 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.094 | 1.12 (0.55) | 0.042 | 0.094 | 1.691 (0.82) | 0.044 |

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.023 | 134.99 (85.59) | 0.117 | 0.007 | −69.724 (153.93) | 0.653 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.015 | 66.37 (54.09) | 0.222 | 0.004 | 23.785 (91.82) | 0.797 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.012 | 76.58 (72.20) | 0.291 | 0.006 | 46.529 (109.06) | 0.672 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.007 | 71.37 (99.35) | 0.474 | 0.003 | 30.962 (146.12) | 0.833 |

| LDL cholesterol | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.040 | 158.88 (72.59) | 0.031 | 0.012 | 27.354 (141.34) | 0.847 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.048 | 109.69 (45.5) | 0.017 | 0.030 | 80.653 (83.39) | 0.338 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.023 | 99.41 (61.43) | 0.108 | 0.017 | 51.923 (99.87) | 0.606 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.009 | 84.18 (84.89) | 0.323 | 0.016 | 66.655 (133.64) | 0.620 |

| log(HDL cholesterol) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.008 | −0.19 (0.29) | 0.506 | 0.101 | −0.936 (0.42) | 0.032 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.032 | −0.33 (0.18) | 0.071 | 0.023 | −0.241 (0.26) | 0.365 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.011 | −0.22 (0.24) | 0.376 | 0.024 | −0.294 (0.31) | 0.354 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.005 | −0.14 (0.34) | 0.688 | 0.017 | −0.311 (0.43) | 0.471 |

R 2: unadjusted R 2; B: unstandardized coefficients beta; SE: unstandardized coefficients Std. Error.

(b).

| Dependent variables | Men (n = 125) | Women (n = 52) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | R 2 | B (SE) | P value | R 2 | B (SE) | P value |

| 24 hr CCR | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.642 | 260.86 (54.29) | <0.001 | 0.340 | 169.5 (114.94) | 0.147 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.621 | 138.8 (35.39) | <0.001 | 0.310 | 22.78 (72.38) | 0.754 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.643 | 221.38 (45.7) | <0.001 | 0.310 | 17.76 (83.87) | 0.833 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.659 | 337.81 (61.38) | <0.001 | 0.309 | 7.43 (112.11) | 0.947 |

| eGFRCG | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.867 | 200.2 (23.38) | <0.001 | 0.800 | 193.98 (46.15) | <0.001 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.891 | 143.99 (13.43) | <0.001 | 0.924 | 193.43 (17.47) | <0.001 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.907 | 205.1 (16.53) | <0.001 | 0.857 | 183.11 (27.77) | <0.001 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.889 | 261.02 (24.76) | <0.001 | 0.910 | 288.32 (29.52) | <0.001 |

| eGFRMDRD | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.923 | 13.96 (14.05) | 0.322 | 0.945 | −7.1 (20.16) | 0.726 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.923 | −11.03 (8.88) | 0.217 | 0.945 | 3.87 (12.42) | 0.757 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.922 | 9.6 (11.86) | 0.420 | 0.946 | 12.38 (14.28) | 0.391 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.923 | 20.57 (16.24) | 0.208 | 0.946 | −14.26 (19.12) | 0.460 |

| log(Cystatin C) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.674 | 0.33 (0.2) | 0.098 | 0.619 | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.681 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.665 | 0.02 (0.12) | 0.852 | 0.639 | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.141 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.670 | 0.21 (0.17) | 0.215 | 0.637 | 0.33 (0.23) | 0.169 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.679 | 0.47 (0.22) | 0.037 | 0.631 | 0.36 (0.3) | 0.242 |

| Uric Acid | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.138 | −3.49 (3.74) | 0.353 | 0.346 | 17.8 (5.5) | 0.002 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.133 | 1.17 (2.3) | 0.612 | 0.319 | 9.93 (3.46) | 0.006 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.132 | 0.87 (3.08) | 0.778 | 0.262 | 8.4 (4.17) | 0.050 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.136 | −3.34 (4.24) | 0.432 | 0.296 | 13.84 (5.44) | 0.014 |

| log(Urine microalbuminuria) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.096 | 2.62 (1.46) | 0.075 | 0.271 | 6.68 (2.1) | 0.003 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.168 | 3.24 (0.89) | <0.001 | 0.168 | 2.47 (1.36) | 0.077 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.142 | 3.64 (1.18) | 0.003 | 0.191 | 3.35 (1.56) | 0.037 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.134 | 4.74 (1.64) | 0.005 | 0.145 | 3.02 (2.14) | 0.164 |

| log(hsCRP) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.073 | 3 (1.39) | 0.033 | 0.114 | 4.25 (1.97) | 0.037 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.094 | 2.3 (0.85) | 0.008 | 0.072 | 1.92 (1.24) | 0.127 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.085 | 2.85 (1.13) | 0.014 | 0.074 | 2.26 (1.43) | 0.121 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.073 | 3.44 (1.58) | 0.031 | 0.104 | 3.82 (1.88) | 0.048 |

| log(Systolic blood pressure) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.017 | 0.14 (0.12) | 0.248 | 0.028 | 0.14 (0.17) | 0.388 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.045 | 0.16 (0.07) | 0.030 | 0.012 | 0.01 (0.1) | 0.927 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.034 | 0.19 (0.1) | 0.066 | 0.022 | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.494 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.037 | 0.27 (0.14) | 0.053 | 0.017 | 0.08 (0.16) | 0.633 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.127 | 27.95 (19.83) | 0.161 | 0.211 | 29.04 (29.34) | 0.328 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.169 | 35.02 (12.26) | 0.005 | 0.197 | 8.09 (18.23) | 0.659 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.132 | 27.86 (16.66) | 0.097 | 0.227 | 28.83 (20.72) | 0.171 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.139 | 43.71 (22.83) | 0.058 | 0.240 | 45.54 (27.46) | 0.104 |

| log(Fasting plasma glucose) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.033 | 0.47 (0.29) | 0.103 | 0.068 | 0.09 (0.41) | 0.826 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.061 | 0.45 (0.18) | 0.014 | 0.068 | 0.08 (0.25) | 0.765 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.100 | 0.8 (0.23) | 0.001 | 0.069 | 0.1 (0.29) | 0.733 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.041 | 0.64 (0.33) | 0.055 | 0.077 | −0.28 (0.38) | 0.469 |

| log(Triglyceride) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.138 | 1.49 (0.46) | 0.002 | 0.436 | 2.25 (0.69) | 0.002 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.090 | 0.57 (0.3) | 0.061 | 0.355 | 0.92 (0.47) | 0.056 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.088 | 0.74 (0.4) | 0.068 | 0.384 | 1.27 (0.52) | 0.018 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.095 | 1.14 (0.55) | 0.040 | 0.351 | 1.32 (0.7) | 0.067 |

| Total cholesterol | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.033 | 133.61 (85.5) | 0.121 | 0.007 | −71.5 (156.05) | 0.649 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.023 | 59.89 (54.46) | 0.274 | 0.004 | 22.75 (96.28) | 0.814 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.021 | 69.07 (72.53) | 0.343 | 0.006 | 45.77 (111.37) | 0.683 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.016 | 59 (99.97) | 0.556 | 0.003 | 29.37 (149.02) | 0.845 |

| LDL cholesterol | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.048 | 157.85 (72.6) | 0.032 | 0.012 | 28.43 (143.31) | 0.844 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.052 | 105.66 (45.9) | 0.023 | 0.033 | 88.74 (87.34) | 0.315 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.029 | 94.18 (61.81) | 0.130 | 0.017 | 54.16 (101.96) | 0.598 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.016 | 75.3 (85.54) | 0.381 | 0.017 | 69.33 (136.28) | 0.613 |

| log(HDL cholesterol) | ||||||

| log(Neck circumference) | 0.023 | −0.2 (0.29) | 0.494 | 0.202 | −0.86 (0.4) | 0.039 |

| log(Body mass index) | 0.051 | −0.36 (0.18) | 0.049 | 0.123 | −0.07 (0.26) | 0.782 |

| log(Waist circumference) | 0.028 | −0.25 (0.24) | 0.305 | 0.128 | −0.18 (0.3) | 0.562 |

| log(Hip circumference) | 0.022 | −0.18 (0.34) | 0.596 | 0.124 | −0.15 (0.41) | 0.724 |

R 2: unadjusted R 2; B: unstandardized coefficients beta; SE: unstandardized coefficients Std. Error.

4. Discussion

Several studies have revealed the relationship between body adipose abnormalities, CVD, and metabolic syndrome [16–29] as well as between cardiometabolic factors and CKD [1, 4, 5, 7–11, 30, 31]. However, there is lack of reporting on the relevance between NC and CKD. This is the first study to report their relationship and it is discovered that NC is associated with indicators of renal disease such as 24 hr CCR, eGFRCG, uric acid, and urine microalbuminuria, in addition to conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as hsCRP, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol.

NC is an alternative measurement for upper-body subcutaneous fat, and therefore NC may play a vital role in CVD clinical prediction [16]. NC as an associated factor for diabetes, after adjusted BMI and waist circumference, was the only risk factor related to type II diabetes mellitus [26]. These results confirmed that NC measurements can be used as an effective clinical screening tool for insulin resistance, and can be used as powerful indicators to improve the screening ability for type II diabetes mellitus. In addition to insulin resistance and type II diabetes mellitus, NC also has associated power to assess cardiometabolic risk [28].

NC also correlated significantly with intima-media thickness of common or internal carotid arteries after BMI and waist circumference adjustment. For every 1-standard deviation unit increase in NC, there is a 0.025 mm thickness increase in common carotid artery, and remaining significant even after BMI adjustment [27]. In a follow-up study involving acute ischemic stroke patients who have a 1-year total mortality of 8.9%, the author discovered that aging and larger neck circumference were more frequent findings among the dead, but not obesity. Therefore, NC is a critical clinical warning factor for fatal outcomes in acute ischemic stroke [25]. Insulin resistance, related with NC, causes arterial stiffness, which in turn has an impact on CKD and even nondiabetic CKD. CKD patients who develop metabolic syndrome would also have a higher risk of arterial stiffness [30].

Although gender differences of anthropometric measures, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and fasting plasma glucose exist, NC is also related to cardiometabolic risk [16] and is a powerful indicator for predicting dyslipidemia. In particular, the correlation between triglycerides and NC is stronger than BMI and waist circumference [28]. Moreover, the relevance and importance of waist circumference and metabolic syndrome to CVD have been discussed previously [32]. One study showed that dual indicators using both triglycerides and waist circumference can assess the risk of coronary artery disease in patients with abdominal obesity. When the Framingham model was used for predicting CVD risk, these dual indicators may help to add associated value. The hypertriglyceridemic-waist phenotype might become a superior health indicator compared to metabolic syndrome [33]. Another study in CKD patients suggested that the hypertriglyceridemic-waist phenotype can be used to evaluate the severity of carotid atherosclerosis and can also be used as an effective indicator to predict CVD risk [31]. Our study showed NC is highly correlated to waist circumference and triglycerides. Therefore, NC may replace waist circumference for phenotyping, especially because this phenotype can be used for both coronary heart disease and CKD. NC is an ideal associated indicator for these two coexisting diseases that are risk factors for each other. Moreover, for patients who are disabled, in serious condition, in particular those who are bedridden, or even in healthy status, this method would be not only simple but also easy to perform with high efficiency and convenience. Therefore, NC may be popularized for clinical applications as an associated indicator of risk for both outcomes.

Based on the eGFRCG equation, we know that weight and eGFR are positively correlated. Specifically, heavier weights correlate with higher eGFRCG among those with the same sex, age, and creatinine level. From Table 2 in this study, we can conclude that NC and weight are positively correlated. Subjects aged <65 years have higher mean NC values and also have higher mean eGFRCG values and eGFRMDRD, indicating that patients with higher NC values usually have better renal function. This means that NC is positively correlated with eGFR. The eGFRMDRD and eGFRCG equations had the gender-specific coefficient of creatinine.

Hoebel et al. have established the cutoffs for NC to evaluate the risk of metabolic syndrome, which were 40 cm and 41 cm for the young and older men, 34 cm and 33 cm for young and older women, respectively [22], which indicates potential uses of NC for other purposes. Body morphologies, other than NC, have an existing normal level; out of which indicate unhealthy conditions. Appropriate cut-off values for NC should be established, in the future, to assess early stage risk of CKD. This cross-sectional study relied on hospital-based samples. It is suggested that a future population-based study and a cohort-based study with follow-up should be conducted, so that the importance of NC to the CKD risk prediction can be validated, and it can be determined whether this importance will change with increasing age. However, in fashion experience and healthy population, the circumference of someone's neck would be about the same as his/her pants width; that is, the waist circumference is about twice the neck circumference [34]. Several studies report similar ratios around 1.9 to 2.1 for circumferences of waist to neck in control groups [16, 17, 21, 22, 29].

Many indicators are testing for obesity and NC is an anthropometric measure of obesity for upper subcutaneous adipose tissue distribution which is associated with cardiometabolic risk, while NC is an alternative and novel indicator to test body fat distribution [17], and it is also a simple and time-saving screening tool to capture overweight or obese patient [20]. NC also is an easy associated tool for metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance [22] and a powerful indicator of atherosclerotic lipid abnormalities and their risk factors [17]. NC is also an independent associated factor for cardiometabolic risk [16, 29] and an effective screening test for cardiovascular risk in children [18] or even in obese children [23]. Studies mentioned above have suggested that NC is a superior indicator for metabolic syndrome in terms of both relevance and significance compared to BMI and waist circumference [17, 19, 21, 24, 28, 35, 36].

5. Conclusions

NC is associated with indicators of CKD for high cardiometabolic risk patients and can be routinely measured as easy as WC in the future.

Conflict of Interests

All contributing authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Schiffrin E. L., Lipman M. L., Mann J. F. E. Chronic kidney disease: effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation. 2007;116(1):85–97. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.678342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai C.-H. Incidence of hypertension, hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia: the results from national survey. Proceedings of the 41st Asia Pacific Consortium for Public Health Conference; 2009; Taipei, Taiwan. NTUH International Convention Center; [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cabrera M. A. S., de Andrade S. M., Mesas A. E. A prospective study of risk factors for cardiovascular events among the elderly. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2012;7:463–468. doi: 10.2147/cia.s37211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCullough P. A., Steigerwalt S., Tolia K., et al. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: data from the kidney early evaluation program (KEEP) Current Diabetes Reports. 2011;11(1):47–55. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0162-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taal M. W., Brenner B. M. Predicting initiation and progression of chronic kidney disease: developing renal risk scores. Kidney International. 2006;70(10):1694–1705. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culleton B. F., Larson M. G., Wilson P. W. F., Evans J. C., Parfrey P. S., Levy D. Cardiovascular disease and mortality in a community-based cohort with mild renal insufficiency. Kidney International. 1999;56(6):2214–2219. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go A. S., Chertow G. M., Fan D., McCulloch C. E., Hsu C.-Y. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(13):1296–1370. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa041031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCullough P. A., Li S., Jurkovitz C. T., et al. CKD and cardiovascular disease in screened high-risk volunteer and general populations: the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) and National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. The American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;51(4, supplement 2):S38–S45. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olechnowicz-Tietz S., Gluba A., Paradowska A., Banach M., Rysz J. The risk of atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. International Urology and Nephrology. 2013;45(6):1605–1612. doi: 10.1007/s11255-013-0407-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarnak M. J., Levey A. S., Schoolwerth A. C., et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease, High Blood Pressure Research, Clinical Cardiology, and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–2169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000095676.90936.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gansevoort R. T., Correa-Rotter R., Hemmelgarn B. R., et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. The Lancet. 2013;382(9889):339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yerkey M. W., Kernis S. J., Franklin B. A., Sandberg K. R., McCullough P. A. Renal dysfunction and acceleration of coronary disease. Heart. 2004;90(8):961–966. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.015503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klop B., Elte J. W. F., Cabezas M. C. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1218–1240. doi: 10.3390/nu5041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cornier M.-A., Després J.-P., Davis N., et al. Assessing adiposity: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation. 2011;124(18):1996–2019. doi: 10.1161/cir.0b013e318233bc6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1956;4(1):20–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/4.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preis S. R., Massaro J. M., Hoffmann U., et al. Neck circumference as a novel measure of cardiometabolic risk: the framingham heart study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(8):3701–3710. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stabe C., Vasques A. C. J., Lima M. M. O., et al. Neck circumference as a simple tool for identifying the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance: results from the Brazilian Metabolic Syndrome Study. Clinical Endocrinology. 2013;78(6):874–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Androutsos O., Grammatikaki E., Moschonis G., et al. Neck circumference: a useful screening tool of cardiovascular risk in children. Pediatric Obesity. 2012;7(3):187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Noun L., Laor A. Relationship of neck circumference to cardiovascular risk factors. Obesity Research. 2003;11(2):226–231. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Noun L., Sohar E., Laor A. Neck circumference as a simple screening measure for identifying overweight and obese patients. Obesity Research. 2001;9(8):470–477. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ben-Noun L. L., Laor A. Relationship between changes in neck circumference and cardiovascular risk factors. Experimental and Clinical Cardiology. 2006;11(1):14–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoebel S., Malan L., de Ridder J. H. Determining cut-off values for neck circumference as a measure of the metabolic syndrome amongst a South African cohort: the SABPA study. Endocrine. 2012;42(2):335–342. doi: 10.1007/s12020-012-9642-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurtoglu S., Hatipoglu N., Mazicioglu M. M., Kondolot M. Neck circumference as a novel parameter to determine metabolic risk factors in obese children. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;42(6):623–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laakso M., Matilainen V., Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. Association of neck circumference with insulin resistance-related factors. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26(6):873–875. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medeiros C. A. M., de Bruin V. M. S., de Castro-Silva C., Araújo S. M. H. A., Chaves Junior C. M., de Bruin P. F. C. Neck circumference, a bedside clinical feature related to mortality of acute ischemic stroke. Revista da Associacao Medica Brasileira. 2011;57(5):559–564. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42302011000500015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preis S. R., Pencina M. J., D'Agostino R. B., Sr., Meigs J. B., Vasan R. S., Fox C. S. Neck circumference and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(1, article e3) doi: 10.2337/dc12-0738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenquist K. J., Massaro J. M., Pencina K. M., et al. Neck circumference, carotid wall intima-media thickness, and incident stroke. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):e153–e154. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vallianou N. G., Evangelopoulos A. A., Bountziouka V., et al. Neck circumference is correlated with triglycerides and inversely related with HDL cholesterol beyond BMI and waist circumference. Diabetes Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2013;29(1):90–97. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou J. Y., Ge H., Zhu M. F., et al. Neck circumference as an independent predictive contributor to cardio-metabolic syndrome. Cardiovascular Diabetology. 2013;12(1, article 76) doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan D. T., Watts G. F., Irish A. B., Ooi E. M. M., Dogra G. K. Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome are associated with arterial stiffness in patients with chronic kidney disease. American Journal of Hypertension. 2013;26(9):1155–1161. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpt077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhe X., Bai Y., Cheng Y., et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist is associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephron Clinical Practice. 2012;122(3-4):146–152. doi: 10.1159/000351042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lassale C., Galan P., Julia C., Fezeu L., Hercberg S., Kesse-Guyot E. Association between adherence to nutritional guidelines, the metabolic syndrome and adiposity markers in a french adult general population. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076349.e76349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arsenault B. J., Lemieux I., Després J.-P., et al. The hypertriglyceridemic-waist phenotype and the risk of coronary artery disease: results from the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2010;182(13):1427–1432. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murakami M., Hikima R., Arai S., Yamazaki K., Iizuka S., Tochihara Y. Short term longitudinal changes in subcutaneous fat distribution and body size among Japanese women in the third decade of life. Journal of Physiological Anthropology and Applied Human Science. 1999;18(4):141–149. doi: 10.2114/jpa.18.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Freedman D. S., Rimm A. A. The relation of body fat distribution, as assessed by six girth measurements, to diabetes mellitus in women. The American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79(6):715–720. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.6.715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fox C. S., Massaro J. M., Hoffmann U., et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;116(1):39–48. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.675355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]