To the Editor:

Despite recent advances in therapy, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), characterized by occlusive vasculopathy of the pulmonary arteries, remains a progressive disease without a cure (1–3). Although currently approved PAH medications have not demonstrated antiremodeling properties in humans, novel antiproliferative strategies have shown some benefits and also raised safety concerns (4–6); for example, none target a genetic predisposition of PAH: dysfunctional bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) signaling.

Loss-of-function mutations in BMPR2 in patients with familial and idiopathic PAH (7–9) are associated with increased pulmonary vasculopathy (10). Furthermore, reduced BMPR2 expression is observed even in patients without a mutation, reinforcing the importance of decreased BMPR2 in PAH (11). In a high-throughput screen of 3,600 drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, we identified low-dose FK506 (tacrolimus) as a potent BMPR2 activator that reversed experimental PAH (12). We therefore hypothesized that low-dose FK506 would be beneficial in patients with PAH by increasing BMPR2 signaling.

On the basis of these findings, we initiated a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial (FK506 [Tacrolimus] in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension [TransformPAH]) to evaluate the safety and tolerability of FK506 in stable patients with PAH. Here, we report our clinical experience with compassionate use of low-dose FK506 in three patients with end-stage PAH who did not qualify for our trial because of the severity of their illness (patient details are provided in the online supplement). We assessed traditional clinical parameters, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, 6-minute-walk distance, serologic biomarkers, and hospital admissions, as well as protocolized cardiac magnetic resonance imaging assessed by blinded readers (13, 14). All patients continued receiving stable doses of PAH medication and diuretics throughout the 12-month period.

The TransformPAH clinical trial was registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 01647945).

Patient 1

Patient 1 is a 36-year-old historically athletic woman, NYHA-IV, with rapidly progressive idiopathic PAH requiring rapid up-titration of epoprostenol and the addition of sildenafil and ambrisentan for recurrent hospitalizations for right ventricular (RV) failure (Figure 1). Despite aggressive treatment, she still reported NYHA-III/IV symptoms, an elevated N-terminal-pro-B type natriuretic peptide, and a Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease Management (REVEAL) risk score of 11, stratifying her as high risk with a potential 1-year mortality risk of 15–30% (3, 15). She was listed for lung transplantation. At that time, she was offered compassionate treatment with FK506 (goal trough blood level, 1.5–2.5 ng/ml).

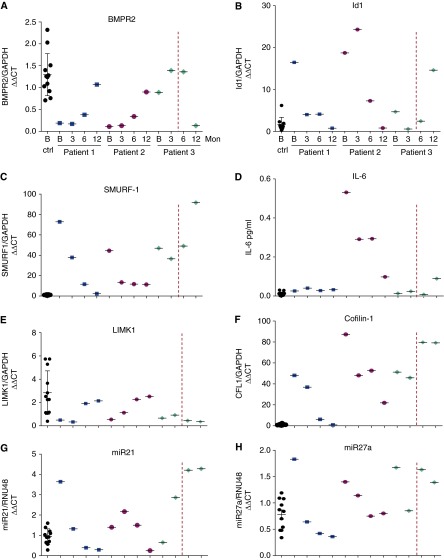

Figure 1.

Timeline of symptoms, clinical parameters, events, and therapies for patients 1–3 before and after initiation of FK506. Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term PAH Disease Management (REVEAL) risk score, %1-year survival: score 1–7 = 95–100% (low risk), 8 = 90–95% (average risk), 9 = 85–90% (moderately high risk), 10–11 = 70–85% (high risk), and 12 or above = <70% (very high risk) (3). Events reported as those related to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH): RHF, HepF, Sync, Tx List, and Tx Hold. Dop = dopamine; ERA = endothelin receptor antagonist; HepF = hepatic failure; NYHA = New York Heart Association functional class; PDE-I = phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor; Prost = prostacyclin; RHF = right heart failure; Sync = syncope; Tx Hold = placed on hold for transplantation because of clinical improvement; Tx List = listed for heart and/or lung transplantation.

Within 1 month of FK506 initiation, she reported substantial improvement in symptoms (Figure 2). Within 2 months, she was placed on hold for transplantation by the lung transplant team. After 3 months, her 6-minute-walk distance improved by 100 m, her N-terminal-pro-B type natriuretic peptide decreased more than 50%, and she reported NYHA-I symptoms (Figure 1; see Figure E1A in the online supplement). During the 12-month period, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed a stable RV ejection fraction, RV end-diastolic volume index, and cardiac index (Figure E1B). Her REVEAL risk score decreased to 3 (range, 3–6), placing her in the low-risk category (Figure 1). Although the 12 months before FK506 were characterized by three hospitalizations for RV failure, the subsequent 12 months were free of any PAH-associated hospitalizations (Figure 1). At the time of this submission, the patient is 27 months from the initiation of FK506, continues to report NYHA-II symptoms, and has been free from hospitalization or clinical deterioration.

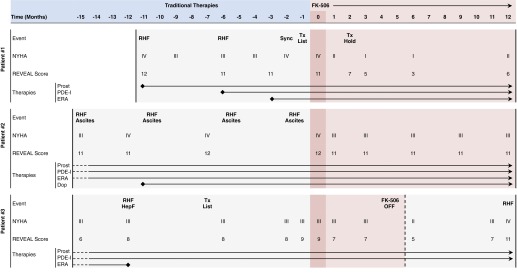

Figure 2.

Biomarkers for patients 1–3 before and after initiation of FK506. (A) Bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2) messenger RNA (mRNA)/glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of healthy control subjects (ctrl) at baseline (B) (n = 12) and three patients (n = 3) at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months (Mon). The red dashed line indicates the time FK506 was stopped in patient 3. (B) Id1/GAPDH mRNA in PBMCs. (C) SMURF-1/GAPDH mRNA in PBMCs. (D) IL-6 plasma levels via ELISA. (E) LIMK1/GAPDH mRNA in PBMCs. (F) Cofilin-1 (CFL1)/GAPDH mRNA in PBMCs. (G and H) miR21/RNU48 and miR27a/RNU48 RNA expression in PBMCs, respectively. CT = cycle threshold; Id1 = inhibitor of differentiation 1; SMURF-1 = SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1; LIMK1 = LIM domain kinase 1; miR = microRNA; RNU48 = small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 48.

Patient 2

Patient 2 is a 50-year-old woman with end-stage systemic sclerosis–associated PAH receiving intravenous treprostinil, sildenafil, and ambrisentan, as well as an intravenous dopamine infusion for end-stage RV failure and hypotension. The patient continued to report NYHA-III/IV symptoms and had an elevated N-terminal-pro-B type natriuretic peptide (range, 4,926–15,161 pg/ml) and four hospitalizations for progressive RV failure and palliative paracenteses (Figure 1). Given the lack of further therapeutic options, she was offered FK506.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and 3 and 6 months showed substantial improvement in RV ejection fraction, stable RV end-diastolic volume index, and improvement in right ventricular stroke volume index and cardiac index (Figure E1B), with a reduction back to baseline at 12 months. Her REVEAL risk score decreased from 12 to 11. At 12-month follow-up, she had stable NYHA-III symptoms, a 94-m increase in 6-minute-walk distance, 30% reduction in her N-terminal-pro-B type natriuretic peptide, and no PAH-related hospitalizations since being on FK506 (Figure 1). The patient is currently 26 months post-FK506 initiation and has not experienced further clinical deterioration.

Patient 3

Patient 3 is a 55-year-old woman with severe end-stage drugs-and-toxins–associated PAH, NYHA-III/IV, who is receiving high-dose intravenous treprostinil and sildenafil, has an intolerance to endothelin receptor antagonists, is listed for lung transplantation, and was offered FK506. Despite initial symptomatic improvement (Figure 1), the patient voluntarily discontinued FK506 after 4.5 months. Unfortunately, during the ensuing 7 months, she showed progressive clinical worsening, culminating in an intensive care unit admission for RV failure and large pericardial effusion. On the patient’s wish, she was restarted on FK506 and is currently 12 months after her second FK506 initiation, feeling much better, with compensated NYHA-II symptoms and without any further hospital admission for RV failure.

Serologic Biomarkers

None of the three patients had mutations in BMPR2, SMAD9, or caveolin-1. We measured BMPR2 expression and specific BMPR2-associated genes and molecules (Id1 [inhibitor of differentiation 1], Smurf-1 [SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1], IL-6, LIMK1 [LIM domain kinase 1], Cofilin-1, and microRNAs 21 and 27a) at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months into FK506 treatment in patients versus healthy controls (n = 12) (see online supplement). Patients had significantly lower BMPR2 messenger RNA expression at baseline (Figure 2), with near normalization of BMPR2 and associated genes after 12 months of FK506 treatment. Strikingly, patient 3, who stopped FK506 after 4.5 months and who worsened clinically during the following 7 months, showed a 12-month BMPR2 profile that was opposite that of patients still receiving FK506 therapy.

Discussion

Our results suggest a potential clinical benefit of low-dose FK506 in end-stage PAH, judged by the patients’ marked clinical response, stabilization in cardiac function, and freedom from hospitalization for RV failure. Despite the overall positive experience, we caution that these findings are highly preliminary. The efficacy of this therapy must be validated in appropriate, well-designed, prospective clinical trials. Our choice of low-dose FK506 was based on data from preclinical studies (12) and the desire to avoid major immunosuppressive adverse effects in patients with indwelling lines. We did not observe an increase in line sepsis or opportunistic infections. We also did not observe serious adverse effects of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, acute kidney injury or worsening of creatinine, an elevated systemic blood pressure, hyperglycemia, hyperkalemia, anemia, or a change in white blood cell count. The currently underway clinical phase IIa trial will address safety and tolerability in greater detail, as even low-dose immunosuppression over time can lead to complications.

This is the first study in patients with PAH that repurposes FK506 to increase BMPR2 signaling. The changes in serologic biomarkers are encouraging and show that we have indeed targeted BMPR2 in patients with reduced levels of BMPR2. It will be of interest to determine whether the same effect can be achieved in patients with documented mutations and whether a subset of patients is particularly sensitive to the beneficial effects of this strategy and could therefore be identified up front as potential “responders” on the basis of BMPR2 levels.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant 1K08HL107450-01 (E.S.), National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant P01 HL108797 (M.R., M.B., and R.T.Z.), a supplemental grant from the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (E.S. and D.S.), a SPARK seed grant from Stanford University (E.S.), and a research grant from the Vera M. Wall Center for Pulmonary Vascular Disease at Stanford (E.S., R.T.Z., and M.R.). A.V.N. is supported by the Netherlands CardioVascular Research Initiative: The Dutch Heart Foundation, Dutch Federation of University Medical Centers, the Netherlands Foundation for Health Research and Development, and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Science.

Author Contributions: E.S., Y.K.S., M.R., and R.T.Z. were responsible for the design, implementation, and analysis of the results. M.A.A. was involved in genetic sequencing. R.D. and P.C.Y. performed the cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scans. M.C.v.d.V., A.V.N., A.J.S., and A.L. were responsible for blinded interpretation of the cardiac magnetic resonance imaging scans. J.L.-B., E.S., and R.T.Z. were responsible for development of the dosing algorithm. E.S. and D.S. performed and interpreted serologic biomarker assays. M.B. was responsible for blood collection and biobanking. All authors contributed to the development of the manuscript.

This letter has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue's table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Simonneau G. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1425–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Manes A, Negro L, Palazzini M, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Branzi A. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:394–403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benza RL, Miller DP, Barst RJ, Badesch DB, Frost AE, McGoon MD. An evaluation of long-term survival from time of diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2012;142:448–456. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schermuly RT, Dony E, Ghofrani HA, Pullamsetti S, Savai R, Roth M, Sydykov A, Lai YJ, Weissmann N, Seeger W, et al. Reversal of experimental pulmonary hypertension by PDGF inhibition. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2811–2821. doi: 10.1172/JCI24838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoeper MM, Barst RJ, Bourge RC, Feldman J, Frost AE, Galié N, Gómez-Sánchez MA, Grimminger F, Grünig E, Hassoun PM, et al. Imatinib mesylate as add-on therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the randomized IMPRES study. Circulation. 2013;127:1128–1138. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghofrani HA, Morrell NW, Hoeper MM, Olschewski H, Peacock AJ, Barst RJ, Shapiro S, Golpon H, Toshner M, Grimminger F, et al. Imatinib in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients with inadequate response to established therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:1171–1177. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0123OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng Z, Morse JH, Slager SL, Cuervo N, Moore KJ, Venetos G, Kalachikov S, Cayanis E, Fischer SG, Barst RJ, et al. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado RD, Aldred MA, James V, Harrison RE, Patel B, Schwalbe EC, Gruenig E, Janssen B, Koehler R, Seeger W, et al. Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:121–132. doi: 10.1002/humu.20285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomson JR, Machado RD, Pauciulo MW, Morgan NV, Humbert M, Elliott GC, Ward K, Yacoub M, Mikhail G, Rogers P, et al. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-beta family. J Med Genet. 2000;37:741–745. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stacher E, Graham BB, Hunt JM, Gandjeva A, Groshong SD, McLaughlin VV, Jessup M, Grizzle WE, Aldred MA, Cool CD, et al. Modern age pathology of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:261–272. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0164OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkinson C, Stewart S, Upton PD, Machado R, Thomson JR, Trembath RC, Morrell NW. Primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with reduced pulmonary vascular expression of type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor. Circulation. 2002;105:1672–1678. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012754.72951.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spiekerkoetter E, Tian X, Cai J, Hopper RK, Sudheendra D, Li CG, El-Bizri N, Sawada H, Haghighat R, Chan R, et al. FK506 activates BMPR2, rescues endothelial dysfunction, and reverses pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3600–3613. doi: 10.1172/JCI65592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kind T, Mauritz GJ, Marcus JT, van de Veerdonk M, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Right ventricular ejection fraction is better reflected by transverse rather than longitudinal wall motion in pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:35. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-12-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauritz GJ, Kind T, Marcus JT, Bogaard HJ, van de Veerdonk M, Postmus PE, Boonstra A, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A. Progressive changes in right ventricular geometric shortening and long-term survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141:935–943. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benza RL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Miller DP, Frost A, Frantz RP, Foreman AJ, Badesch DB, McGoon MD. The REVEAL Registry risk score calculator in patients newly diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2012;141:354–362. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]