Abstract

Introduction:

Coexistence of Wilson’s disease and autoimmune hepatitis has been rarely reported in English literature. In this group of patients, there exist features of both diseases and laboratory and histopathological studies may be misleading. Medical treatment for any of these entities, per se, may result in poor response. Therefore, by considering the acute hepatitis resembling Wilson’s disease and autoimmune hepatitis, simultaneous therapy with immunosuppressive and penicillamine may have a superior benefit.

Case Presentation:

We present the case of a 10-year-old boy with nausea, vomiting, yellowish discoloration of skin and sclera, abdominal pain and tea-color urine. Physical examination showed mild hepatomegaly and right upper quadrant tenderness. Laboratory and histochemical studies and atomic absorption test were done and the results were highly suggestive of both Wilson’s disease and autoimmune hepatitis, in him.

Conclusions:

This case study highlights, although rare, the coexistence of Wilson’s disease and autoimmune hepatitis and the need to maintain a high level of awareness of this problem. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider this type of hepatitis in rare patients, with dominant features of both diseases at the same time.

Keywords: Hepatitis, Hepatolenticular Degeneration; Autoimmune

1. Introduction

Wilson’s disease (WD) and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) are considered as the common causes of acute and chronic hepatitis. The coexistence of these diseases in one patient, at the same time, is rare. Hepatocyte necrosis and intracellular antigen exposure to immune system is seen in WD and results in low titer autoantibody production. This finding is a misleading point in differentiating AIH from WD (1). In this group of patients, with WD, there is no evidence of dermatologic manifestations of autoimmune disorders and the serum level of immunoglobulins is not elevated. On the other hand, there are several cases of WD that were initially diagnosed as AIH and partial response to steroids and azathioprine was achieved in these patients. Therefore, it is highly recommended to screen WD in patients labeled as AIH, especially when there is poor response to immunosuppressive treatments. In this situation, combined treatment with steroid and d-penicillamine may be effective (2). Here, we present a case of acute hepatitis with dominant features of both WD and AIH.

2. Case Presentation

A 10-year-old boy presented to our tertiary children hospital with a history of nausea, vomiting, and tea-color urine, since 1 day before admission. His parents were not relatives. His father was suffering from insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. The patient was icteric and had an ill looking appearance, with not toxic facial traits. Clinical examination revealed body temperature 37°C, blood pressure 100/60 mmHg, heart rate 100 beats/min and respiratory rate 20/min. The spleen was not palpable, although mild hepatomegaly was detected. Findings in favor of chronic liver disease, such as spider angioma, caput medusa, palmar erythema and ascites were absent in abdominal examination. Laboratory investigations revealed mild anemia, abnormal coagulation profile, direct hyperbilirubinemia and liver enzymes and also, reversed albumin globulin ratio (albumin = 3 g/dL and globulin = 4.9 g/dL). Laboratory investigations are summarized in Table 1. Serologic testing for viral hepatitis A virus, hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus were negative. An advanced laboratory investigation, including antinuclear antibody and other autoantibodies, serum ceruloplasmin, serum copper, and 24-hour urine copper was performed. Results were summarized in Table 2. There was no specific key point in his past medical history or his familial history that would guide our investigation for a specific diagnosis. Therefore, we evaluated him for WD, AIH and viral hepatitis, in primary investigation.

Table 1. Primary Laboratory Investigation a.

| Marker | Value | Marker | Value | Marker | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC | 7.1 × 103 /microL | AST | 139 mg/dL | BUN | 9 mg/dL |

| RBC | 3.6 × 106/microL | ALT | 133 mg/dL | Cr | 0.3 mg/dL |

| Hb | 8.9 g/L | Uric acid | 1.8 mg/dL | Na | 137 meq/L |

| Platelet | 151 × 103/microL | Bilirubin (total, direct) | (7.3, 2.5) mg/dL | K | 4.3 meq/L |

| Reticulocytes | 2.7% | Alkaline phosphatase | 286 IU/L | Ca | 7.8 mg/dL |

| MCV | 99.7 fL | BS | 72 mg/dL | Phosphate | 1.9 mg/dL |

| Coombs (direct, indirect) | Neg. | PT, INR | 19.5 s, 2.02 | Total protein | 7. 9 g/dL |

| ESR | 54 mm/h | PTT | 53 s | Albumin | 3 g/dL |

a Abbreviations: ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; BS, blood sugar; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Ca, calcium; Cr, creatinine; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; Hb, hemoglobin; INR, international normalized ration; K, potassium; MCV, mean cell volume; Na, sodium; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RBC, red blood cell; and WBC, white blood cell.

Table 2. Specific Laboratory Investigation a.

| Marker | Value | Marker | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANA | 1/160 | Ceruloplasmin | 0.2 g/L |

| AMA | 1/160 | 24hr Urine Copper | 1600 microgr/d |

| ASMA | 1/80 | HCV-Ab IgM | 0.09 |

| Anti-LKM1 | 1/20 | Alpha 1 antitrypsin genotyping | MM-Pi |

| HAV Ab (IgM) | 0.3 | ||

| HBs Ag (ECL) | 0.9 | ||

| HBs Ab (ECL) | 23.9 |

a Abbreviation: ANA, anti-nuclear antibody; AMA, anti-mitochondrial antibody; ASMA, anti-smooth muscle antibody; Anti-LKM1, anti-liver kidney microsome type 1 antibody; ECL, electrochemiluminescence; HAV Ab, hepatitis A virus antibody; HBs Ab, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBs Ag, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV-Ab, hepatitis C virus antibody; and IgM, immunoglobulin M.

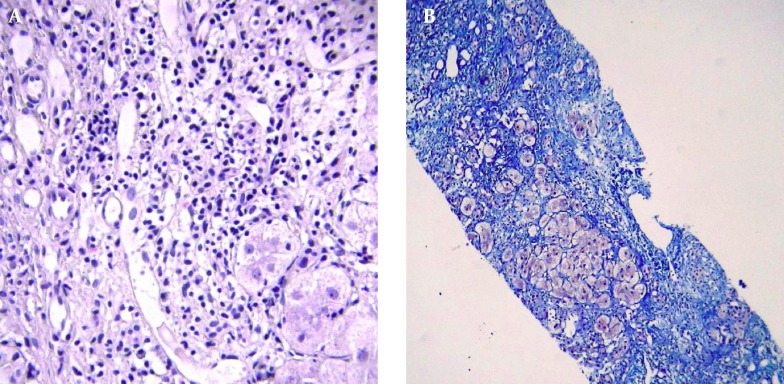

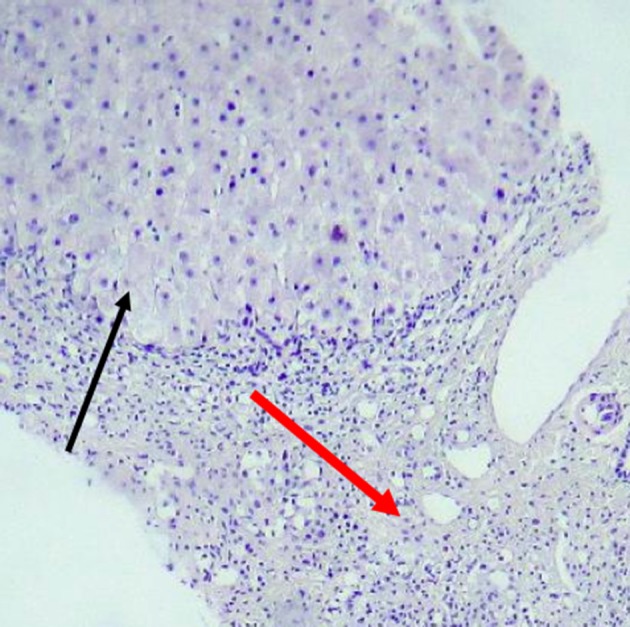

Liver span was about 120 mm, on ultrasonography, with no space-occupying lesion and homogenous echo pattern parenchyma. Spleen size was in the upper limit of normal, with normal parenchyma. Hydrops of gallbladder was seen. In slit-lamp examination by ophthalmologist, the Kayser-Fleischer ring was seen in upper and lower parts of cornea. Finally, liver biopsy was performed and histopathologic studies revealed fibrous bands encircling clusters of hepatocytes and regenerative nodules. Moderate to severe lymphocyte infiltrations and mild infiltration of eosinophil and neutrophils resulted in interface hepatitis. Binuclear and multi-nuclear hepatocytes were seen, with feathery degeneration in several cells. In specific staining of tissue, no finding in favor of copper rich cells was seen. Histochemical analysis with rhodamine and orcein was negative (Figures 1 and 2). However, the amount of copper in dry liver tissue was about 20 times the upper limit of normal. Scoring system for this patient was done and the score of 7 was reached for him, in both of WD and AIH scoring systems [according to the international scoring system, the score ≥ 7 are diagnostic for AIH and the score > 4 is considered positive for WD (3, 4)].

Figure 1. Liver Tissue With Distorted Architecture and Presence of Wide Bands of Fibrous Tissue (Red Arrow) Infiltrated by Lymphomononuclear Cells.

Hepatic Nodule is seen in upper part (black arrow).

Figure 2. A, Moderate Infiltration of Lymphomononuclear Cell in Fibrous Septae, Resulting in Interface Hepatitis; B, Trichrome Stain Shows Marked Fibrosis of Liver Encasing Nodules and Single Hepatocytes (Blue Areas).

By considering concomitant WD and AIH, we started oral prednisolone (1 mg/Kg/day) and azathioprine (1 mg/kg) and d-penicillamine for the patient, and an acceptable response was reached. Liver enzymes declined dramatically, after 20 days of treatment, and changed to near normal levels, after 6 months of medical therapy (aspartate transaminase = 54 mg/dL and alanine transfersase = 57 mg/dL). Prothrombin time and international normalization ratio changed to 17.5 seconds and 1.6, respectively, after administration of treatment and, at the end of 6 months of treatment, they were 14 seconds and 1.23, respectively. Also, the total and direct bilirubin changed to 0.7 and 0.2 mg/dL, at 6 months.

3. Discussion

Acute hepatitis has a wide variety of etiologies. Therefore, the correct diagnosis and selecting the appropriate therapy remains a clinical dilemma that pediatric gastroenterologists are faced in their practice with it (3, 5). There are few cases with classical manifestations of WD and several features of AIH, simultaneously. In this group of patients with WD, more convincing features of AIH are present and initial treatment with immunosuppressive medication may result in relative improvement (2). Differentiating these two entities is important. Autoantibody can be positive in WD due to hepatocyte necrosis, especially in early stage of this disease. Liver biopsy and histochemical staining is another diagnostic modality. Histochemical stains for copper or copper-associated proteins, such as rhodamine, provide qualitative evidence of increased liver copper (6). However, despite elevated hepatic copper content, these stains are frequently negative in patients with WD. Another test, which is confirmatory in patients with WD, is the 24-hour urine copper. This test is abnormal in 80 - 85% of untreated patients with WD. However, in any severe icteric hepatitis, abnormal copper metabolism may occur. Although the 24-hour urine copper in acute icteric hepatitis is occasionally increased, the level does not exceed the value of 200 microgram/24 hour (7, 8). In relation to a certain degree of overlapping between these two entities, it is highly recommended to screen for WD, particularly when poor response to steroid treatment is seen in patients with AIH (2, 9, 10). On the other hand, there are several cases of WD patients, who are suffering from superimposed manifestations of AIH. In this group of patients, combination therapy with penicillamine and steroid may be of benefit (1, 6). The coexistence of WD and AIH is not the sole example of concomitant presentation of two diseases (7). There are several other situations where the coexistence of two hepatic diseases in the same patient, at the same time, has been reported in the literature. The other example on this issue is the simultaneous presentation of AIH and concomitant non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (11). Steroids, as the mainstay of treatment in AIH, can result in insulin resistance, obesity, and fatty liver. This predisposes these patients to NAFLD. On the other hand, the incidence of obesity and NAFLD, as its complication, is increasing in the general population. Therefore, it is reasonable to investigate AIH associated with NAFLD, before starting therapy. Liver biopsy is the gold standard the case (12).

The observation of this young patient, in our practice, and the thorough review of the literature lead to the conclusion that physicians should consider coexistence of WD and AIH in patients with several difficulties in establishing the correct diagnosis.

Although the coexistence of WD and AIH is rare, we need to maintain a high level of awareness of this problem. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider this type of hepatitis in rare patients with dominant features of the diseases, at the same time, and start medical therapy for both of them.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Acquisition of data: Peiman Nasri. Drafting of the manuscript: Amir Hossein Hosseini. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Farid Imanzadeh, Naghi Dara, Peiman Nasri, Amir Hossein Hosseini. Administrative, technical, and material support: Ali Akbar Sayyari. Study supervision: Farid Imanzadeha.

References

- 1.Yener S, Akarsu M, Karacanci C, Sengul B, Topalak O, Biberoglu K, et al. Wilson's disease with coexisting autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(1):114–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milkiewicz P, Saksena S, Hubscher SG, Elias E. Wilson's disease with superimposed autoimmune features: report of two cases and review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(5):570–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts EA, Schilsky ML, American Association for Study of Liver D. Diagnosis and treatment of Wilson disease: an update. Hepatology. 2008;47(6):2089–111. doi: 10.1002/hep.22261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Pares A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2008;48(1):169–76. doi: 10.1002/hep.22322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halimiasl A, Ghadamli P, Afshar SE, Moussavi F, Hosseini AH. A Neglected Case of Wilson Disease. J Compr Ped. 2013;4(3):143–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheinberg IH, Sternlieb I. Wilson's Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deutsch M, Emmanuel T, Koskinas J. Autoimmune Hepatitis or Wilson's Disease, a Clinical Dilemma. Hepat Mon. 2013;13(5):e29043. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.7872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh V, Bhattacharya SK, Sunder S, Kachhawaha JS. Serum and urinary copper in acute hepatic encephalopathy. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990;38(7):467–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Santos RG, Alissa F, Reyes J, Teot L, Ameen N. Fulminant hepatic failure: Wilson's disease or autoimmune hepatitis? Implications for transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9(1):112–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wozniak M, Socha P. [Two cases of Wilson disease diagnosed as autoimmune hepatitis]. Przegl Epidemiol. 2002;56 Suppl 5:22–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamali R. Inappropriate Long-Term Steroid Therapy in Autoimmune Hepatitis Might Cause the Development of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; A Challenging Situation. Thrita J of Med Sci. 2012;1(4):111–2. doi: 10.5812/thrita.10391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shafiei M, Alavian SM. Autoimmune hepatitis in Iran: what we know, what we don't know and requirements for better management. Hepat Mon. 2012;12(2):73–6. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]