Abstract

The distinct characteristic of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in South Korea is that it not only involves intra-hospital transmission, but it also involves hospital-to-hospital transmission. It has been the largest MERS outbreak outside the Middle East, with 186 confirmed cases and, among them, 36 fatal cases as of July 26, 2015. All confirmed cases are suspected to be hospital-acquired infections except one case of household transmission and two cases still undergoing examination. The Korean health care system has been the major factor shaping the unique characteristics of the outbreak. Taking this as an opportunity, the Korean government should carefully assess the fundamental problems of the vulnerability to hospital infection and make short- as well as long-term plans for countermeasures. In addition, it is hoped that this journal, Epidemiology and Health, becomes a place where various topics regarding MERS can be discussed and shared.

Keywords: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus, Outbreak, Hospital infection, Epidemiology, Statistics, Korea

INTRODUCTION

The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is an RNA virus in the family of Coronaviridae, which was first reported in Saudi Arabia [1]. Information on the mode of transmission of the virus remains limited at the moment. Furthermore, there is no effective medication or vaccine against MERS, and it shows a high case fatality rate of 40% [2-4].

It was May 20, 2015 when the first MERS patient was confirmed in Korea. As of July 26, within approximately two months, 186 cases have been confirmed, including 36 deaths and 138 completely recovered cases. Among the remaining 12 patients still under treatment, 9 are in stable condition but 3 are unstable. Currently, there are only one person in quarantine, and 16,692 people have been released [5]. Hospital-to-hospital transmission occurred in 17 hospitals, all of which originated in one hospital.

Characteristics of confirmed cases

Out of the 186 confirmed cases as of July 26, 2015, 111 were male and 75 were female, and the confirmed cases occurred most in those in their 50s among males and in those in their 60s among females. One male patient was in the 10 to 19 age range. Out of 186 confirmed cases reported, 28 were first generation cases (15.1%) infected by the index case, 125 second generation cases (67.2%), and 32 third generation cases (17.2%). In two additional cases, the modes of infection are not certain yet. There are 82 cases (44%) who were admitted (or treated) in the same hospital with a confirmed case, 71 cases (38%) who are family members, health care aides, or visitors, and 31 cases (17%) who are medical staff.

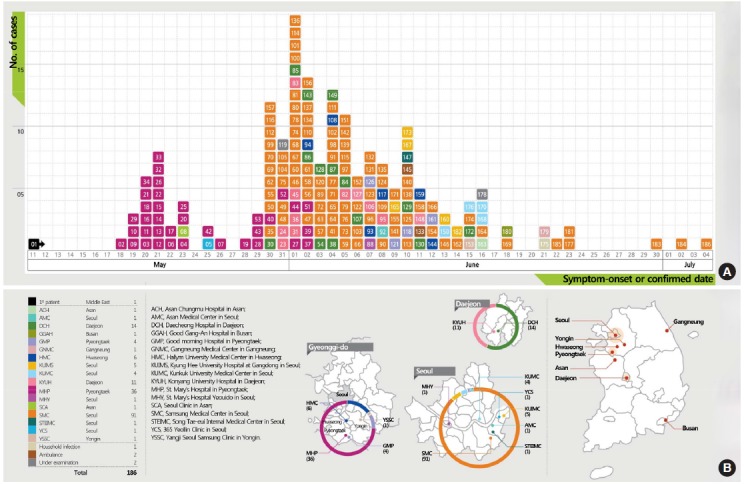

The number of confirmed cases associated with each hospital that has been affected by the outbreak are as follows: 36 cases (19.4%) originated at Pyeongtaek St. Mary’s Hospital where the outbreak was started by the index case, 91 cases (48.9%) at Samsung Medical Center by the 14th confirmed case who was infected at Pyeongtaek St. Mary’s Hospital, and 25 cases (13.4%) at Daecheong Hospital and Konyang University Hospital by the 16th confirmed case who was also infected at Pyeongtaek St. Mary’s Hospital. Furthermore, 11 cases (5.9%) at KunKuk University Medical Center, Kyung Hee University Hospital and ambulance are quaternary cases who were infected by the 76th confirmed case, who was infected at Samsung Medical Center by the 14th confirmed case. Twenty additional cases were distributed among 11 other hospitals or ambulance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Epidemic curve.

Among the confirmed cases, 77 patients (41%) had underlying diseases, and the most common initial symptoms included fever (93.5%), followed by cough (41.4%), myalgia (25.9%), sputum (18.8%), diarrhea (11.8%), shortness of breath (7.5%), and nausea and vomiting (7.5%).

Characteristics of deaths

Up until July 26, 36 cases had died out of 186, marking a case fatality rate of 19.4.%, but when the 12 cases under treatment are excluded from denominator, the case fatality rate becomes 20.7%. The case fatality rate was 29.3% among patients, 15.5% among family members, health care aides, or visitors, and 3.2% among medical staff. Among the medical staff, the death case was a 70 years old male driver of an ambulance. The case fatality rate was 21.6% among males, 16.0% among females, 77.8% among those in their 80s or beyond, 36.7% in those in their 70s, 30.6% in those in their 60s, 14.6% in those in their 50s, and 3.3% in patients in their 40s. Out of 77 patients with underlying diseases, 26 patients (33.8%) died, and out of 109 patients without underlying diseases, 10 patients (9.2%) died.

Epidemiological characteristics

The incubation period, that is, the duration from the midpoint of the exposure to the symptom onset, was 6.5 days (median; range, 2 to 16 days). The median time from symptom onset to confirmation was 5 days (0 to 17 days), that from symptom onset to death was 13 days (1 to 41 days), and that from symptom onset to discharge from the hospital was 20 days (8 to 41 days).

Characteristics of the outbreak

The MERS outbreak in Korea can be characterized by intra-hospital transmission as well as hospital-to-hospital transmission due to movement of cases from one hospital to another. Out of 186 cases, the majority are hospital-acquired infections: Only one patient is suspected of household transmission, and for two patients, the modes of transmission are still under examination. Among the latter two, one case is suspected to have been a community acquired infection by an unknown route. Specifically, the 1st generation cases infected by the index case, the 2nd generation cases infected by three of the 1st generation cases, and the 3rd generation cases infected by one of the 2nd generation cases comprise 87.6% of the total confirmed cases. This is similar to the main mode of transmission of the patients reported in Saudi Arabia in 2014, which involved super-spreaders and nosocomial transmission [6]. Specifically, the majority of people who transmitted the infection to many other people had close contact with the patients at the hospital after their pneumonia had progressed [7].

Based on this fact, the most important intervention for preventing the spread of the disease is to identify patients who show initial symptoms early on and to provide treatment in isolation before they progress to a severe status.

Causes of the outbreak

The large-scale infection of MERS in Korea is due to intra-hospital infection as well as hospital-to-hospital transmission. The reason that the MERS-infected patients at the Pyeongtaek St. Mary’s Hospital were not controlled and they could visit many different hospitals is because when the index case was confirmed on May 20, the people considered to be close contacts who needed to be quarantined were limited only to the patients and the families in the same hospital room and the medical staff who interacted with them. This was noticed only after another confirmed case was identified in another hospital room on May 28. However, this was already after some infected cases moved to other hospitals without having been informed about MERS. The initial criteria for quarantine was limited to only close contacts,—of being within two meters for more than an hour—, and casual contacts, —of being within the contaminated environments from confirmed case—, were not included. However both contacts should be in quarantine based on Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines [8]. In addition, the base causes of the spread of infection by the MERS infected patients as they moved throughout the country are associated with the Korean health care system, which is vulnerable to hospital-acquired infection, as well as with the cultural characteristics of Korea. Specifically, first of all, all Korean citizens are able to receive medical treatment at a relatively low cost through the nationwide health insurance system. However, in order to reduce costs, more than 50% of hospital rooms have more than 4 beds per room, and the family members of the patients are responsible for providing some care for the patients. Thus, hospital rooms are always crowded with patients as well as their families or privately hired health care aides taking care of the patients. Secondly, the Korean health care delivery system is very loose, in that patients themselves can pick and choose the hospitals that they want to visit. In order to visit tertiary general hospital after primary health care, a referral slip by a doctor is required, but one can be directly treated or admitted to tertiary hospitals without the referral slip if a patient visits the emergency room first. Therefore, many patients go directly to the emergency room in order to be treated at large tertiary hospitals. Thirdly, except for drug utilization reviews, which provide a comprehensive review of patients’ prescription and medication data to prevent duplicated drug prescriptions, information regarding patients’ past disease history, response to certain medications, or the results of examinations are not shared between hospitals. Finally, it is a Korean custom to pay a visit to patients in the hospital out of a sense of duty; thus many visitors come to hospitals. This is another factor that causes crowding in hospitals.

Plan for future countermeasures

The current MERS countermeasure plan provides quarantine criteria without considering the differences between hospital-acquired infection and community-acquired infection. While the current revised guideline seems appropriate in the case of community-acquired infection, it is necessary to use broader criteria for quarantine in the case of hospital-acquired infection [9]. The response to new infectious disease cannot always be perfect. However, it is possible to minimize the damage if we do our best to prepare for the situation. The uncontrollable spread of the outbreak due to the failures of initial epidemiologic investigation and preventive measures as well as the characteristics of the Korean health care system have many important implications. Many experts and organizations are proposing various solutions, and the government, after accepting these suggestions, has started to assess of the entire health care system. However, we must address the root cause rather than providing temporary solutions. In addition, a number of varying lines of research will be conducted based on the experience of the MERS outbreak. The journal Epidemiology and Health is planning to create a separate section dedicated to the MERS outbreak so that related studies can be easily accessible and readily available to researchers around the world. We welcome submissions on topics related to MERS.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the epidemiologic investigators, all of the civil servants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and members of the Korean Society for Preventive Medicine, as well as the members of the Korean Society of Epidemiology for their dedicated efforts in investigation of the MERS outbreak and prevention of its spread.

Footnotes

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material (Korean version) is available at http://www.e-epih.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Groot RJ, Baker SC, Baric RS, Brown CS, Drosten C, Enjuanes L, Fouchier RA, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J Virol. 2013;87:7790–7792. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01244-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: epidemiology and disease control measures. Infect Drug Resist. 2014;7:281–287. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S51283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [cited 2015 Jul 20] Available from: http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for hospitalized patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) [cited 2015 Jul 20] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/infection-prevention-control.html.

- 5.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MERS statistics; 2015 Jul 26 [cited 2015 Jul 26] Available from: http://www.mers.go.kr/mers/html/jsp/Menu_C/list_C4.jsp?menuIds=&fid=5767&q_type=&q_value=&cid=64419&pageNum=

- 6.Al-Tawfiq JA, Perl TM. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in healthcare settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28:392–396. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Em SJ, Lee YS. Surveillance for peumonia patients. News1 Korea; 2015 Jul 17 [cited 2015 Jul 26] Available from: http://news1.kr/articles/?2333841 (Korean)

- 8.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Guideline for management of MERS. Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. p. 28. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guideline for management of MERS; 2015 Jun 7 [cited 2015 Jul 20] Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr/CDC/info/CdcKrHealth 0289.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1132-MNU1013-MNU1913&fid=5742&q_type=title&q_value=%EC%A7%80%EC%B9%A8&cid=63696&pageNum= (Korean)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.