Abstract

AIM: To assess the efficacy of full-thickness excision using transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) in the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

METHODS: We analyzed the data of all rectal neuroendocrine tumor patients who underwent local full-thickness excision using TEM between December 2006 and December 2014 at our department. Data collected included patient demographics, tumor characteristics, operative details, postoperative outcomes, pathologic findings, and follow-ups.

RESULTS: Full-thickness excision using TEM was performed as a primary excision (n = 38) or as complete surgery after incomplete resection by endoscopic polypectomy (n = 21). The mean size of a primary tumor was 0.96 ± 0.21 cm, and the mean distance of the tumor from the anal verge was 8.4 ± 1.4 cm. The mean duration of the operation was 57.6 ± 13.7 min, and the mean blood loss was 13.5 ± 6.6 mL. No minor morbidities, transient fecal incontinence, or wound dehiscence was found. Histopathologically, all tumors showed typical histology without lymphatic or vessel infiltration, and both deep and lateral surgical margins were completely free of tumors. Among 21 cases of complete surgery after endoscopic polypectomy, 9 were histologically shown to have a residual tumor in the specimens obtained by TEM. No additional radical surgery was performed. No recurrence was noted during the median of 3 years’ follow-up.

CONCLUSION: Full-thickness excision using TEM could be a first surgical option for complete removal of upper small rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

Keywords: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery, Rectal neuroendocrine tumor, Full-thickness excision, Primary excision, Complete excision, Retrospective study

Core tip: Rectal neuroendocrine tumors increase quickly and steadily. Although transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) was widely used for rectal neoplasms, the application of TEM in the full-thickness excision of rectal neuroendocrine tumors has not been well investigated. We analyzed data of all rectal neuroendocrine tumor patients who underwent local full-thickness excision using TEM as a primary excision or as complete surgery after incomplete resection by endoscopic polypectomy. The results suggested that full-thickness excision using TEM is a safe, minimally invasive procedure which could achieve complete resection, and might be a first surgical option for complete removal of higher rectal neuroendocrine tumors of less than 2 cm.

INTRODUCTION

A rectal neuroendocrine tumor is rare in the general population, but its incidence is increasing quickly and steadily worldwide[1]. It has been reported that the age-adjusted incidence of rectal neuroendocrine tumor has increased about 10-fold over the last 35 years[2]. This dramatic increase may be attributable to the introduction of colonoscopic screening and heightened awareness of the importance of early detection of colorectal disease, as 50% or more of rectal neuroendocrine tumors were diagnosed incidentally[3].

Surgical removal of a single lesion is the only guaranteed curative option[4]. For small rectal neuroendocrine tumors without blood vessel invasion and metastatic spread, local resection should be adequate[5]. Endoscopic polypectomy has been widely used for treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. However, most neuroendocrine tumors arise from the deep portion of the epithelial glands penetrating the muscularis mucosa into the submucosal layer where the tumor forms a nodular lesion[6,7]. Hence, the intrinsic limitations of the conventional endoscopic polypectomy result in a high chance of incomplete resection[6,8]. The rate of incomplete resection or unclear surgical margin and curability have been reported to be 24%-42% because of limited resection up to the submucosal layer and a burn effect[9,10].

With the introduction of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), the clinical efficacy of TEM for benign neoplasms has been widely reported. The TEM procedure provides several advantages over conventional excision by offering much improved visualization, exposure, and access to higher lesions in the rectum[11]. Moreover, the TEM procedure could achieve accurate determination of margins and full-thickness excision with the possibility of suturing[4]. Full-thickness excision using TEM enables a much greater degree of resection, ensuring more satisfactory oncological results for lesions with malignant potential. However, the application of TEM in full-thickness excision has not been well investigated. We here report our clinical experiences of the largest cohort of rectal neuroendocrine tumors treated by full-thickness excision using TEM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Between December 2006 and December 2014, full-thickness excision using TEM was performed in 59 patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Their clinical data were reviewed retrospectively, including: patient demographics, tumor characteristics, blood loss during surgery, operation time, postoperative outcomes, pathological results, and follow-up clinical notes.

Surgical techniques

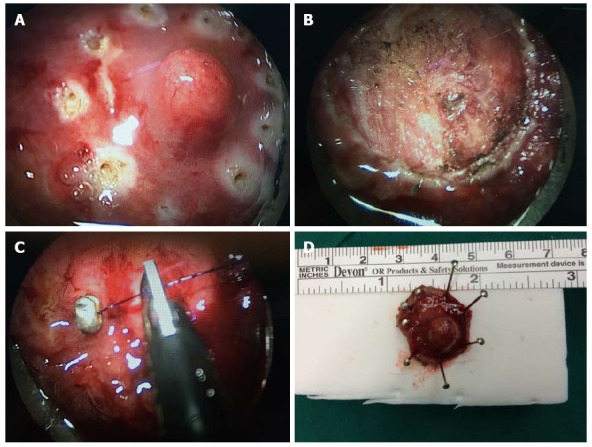

Routine colonoscopy was performed preoperatively to evaluate the location and size of a lesion, and endoscopic ultrasonography was used to evaluate the invasion depth or the status of vessels and lymph nodes. The operation was performed under general anesthesia. The patient was positioned such that the lesion was situated at the bottom of the operative field. Before resection, the scheduled resection area, including the tumor and a clear margin of at least 0.5 cm, was marked by coagulation dots using a needle electrode (Figure 1). Then full-thickness excision down to the outer fatty tissues was performed. The rectal wall was closed by a continuous running suture with absorbable thread and silver clips in place of knots. Tight sutures in the transverse direction were crucial for preventing wound bleeding, dehiscence, and stenosis of the rectal lumen.

Figure 1.

Full-thickness excision of a rectal neuroendocrine tumor visible under transanal endoscopic microsurgery. A: The tumor and a clearance margin marked by coagulation dots using a needle electrode; B: After full-thickness excision with neat surgical margins; C: After suturing the rectal wall. The leakage from the suture line will be negligible; D: The neuroendocrine tumor removed completely with safe surgical margins.

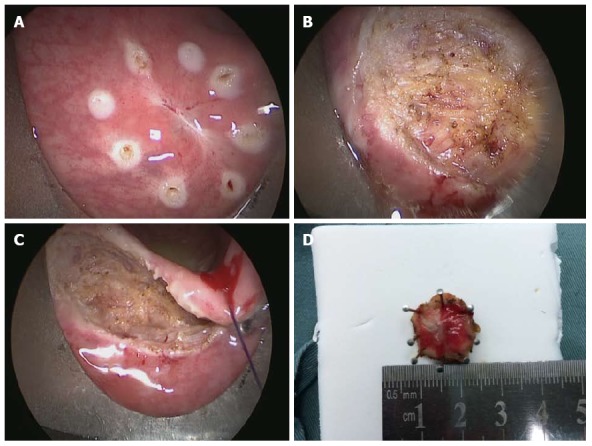

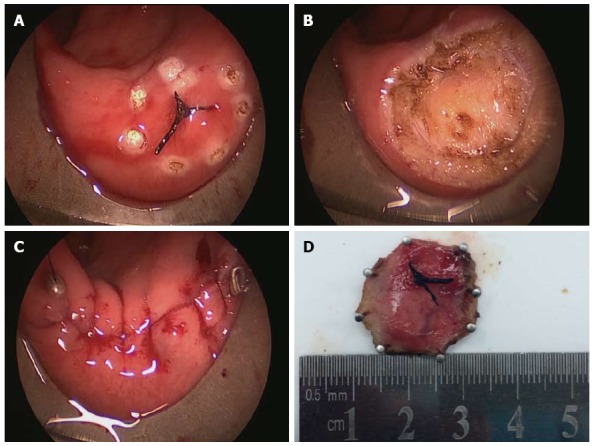

The full-thickness excision could also be used to remove the residual tumor after endoscopic polypectomy (Figure 2) or an unobtrusive neuroendocrine tumor arising in the deep portion of the epithelial glands diagnosed by transrectal ultrasound (Figure 3). A mark using a tattoo or thread knot was strongly recommended during endoscopic polypectomy or diagnosis of unobtrusive tumor to facilitate localization.

Figure 2.

Full-thickness excision of a rectal lesion after incomplete resection. A: The scar site after endoscopic polypectomy where the resection margin was identified as tumor positive; B: Fat tissue outside the rectal wall; C: Suturing of the rectal wall; D: Specimen obtained by transanal endoscopic microsurgery with a safe margin.

Figure 3.

Full-thickness excision of an unobtrusive rectal neuroendocrine tumor using transanal endoscopic microsurgery. A: The unobtrusive tumor found by trans-rectal ultrasound and marked by thread; B: The defect after full-thickness excision; C: Completion of suturing of the rectal wall; D: The neuroendocrine tumor removed completely with safe surgical margins.

Statistical analysis

Data were summarized and analyzed using the Student t test, Fisher’s exact test, and the χ2 test, which were performed with SPSS statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Differences with a P value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The study was reviewed and approved by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Review Board. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Zhou JL from Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

RESULTS

Patients and demographics

Between December 2006 and December 2014, 59 consecutive patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors underwent full-thickness excision using TEM (Table 1). The median age at diagnosis was 55 years (range, 31-70 years). Most tumors were diagnosed incidentally (47, 79.7%), and a minority were associated with neuroendocrine tumor syndrome (12, 20.3%). A total of 38 patients underwent TEM for primary tumor excision (primary excision group); the remaining 21 patients underwent complete resection (complete surgery group) after endoscopic polypectomy by gastroenterologists in other hospitals. The histopathological results showed that the tumor was a typical neuroendocrine tumor, and the resection margin was microscopically identified as tumor positive. These patients were referred to us for complete resections.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Total (n = 59) |

Purpose of TEM |

P value | ||

| Primary excision (n = 38) | Completion surgery(n = 21) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Male/female (n) | 32/27 | 21/17 | 11/10 | NS |

| Age (yr)1 | 55 (31-70) | 47 (31-68) | 53 (35-70) | NS |

| Tumor | ||||

| Size of tumor (cm) | 0.96 ± 0.21 | 1.01 ± 0.21 | 0.89 ± 0.19 | 0.04 |

| Location (A/P) | 24/35 | 15/23 | 9/12 | NS |

| Distance from AV (cm) | 8.4 ± 1.4 | 8.2 ± 1.3 | 8.9 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Central umbilication (yes/no) | 6/53 | 4/34 | 2/19 | NS |

Values are median (range). TEM: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery; A: Anterior wall; P: Posterior wall; AV: Anal verge; NS: Not significant.

Tumor characteristics

The characteristics of the removed neoplasms are shown in Table 2. The mean tumor size was 0.96 ± 0.21 cm, the anal verge to the distal tumor margin was 8.4 ± 1.4 cm, and 24 tumors were located on the anterior wall of the rectum. In the complete surgery group, the mean size of the primary tumor was 0.89 ± 0.19 cm, which was statistically smaller than that in the primary excision group (1.01 ± 0.21, P = 0.04). This might be the reason why endoscopic polypectomy was initially given.

Table 2.

Operative details and pathological findings

| Total (n = 59) |

Purpose of TEM |

P value | ||

| Primary excision (n = 38) | Completion surgery (n = 21) | |||

| Operative details | ||||

| Surgical duration (min) | 57.6 ± 13.7 | 59.6 ± 10.7 | 54.0 ± 17.7 | NS |

| Blood loss (mL) | 13.5 ± 6.6 | 13.2 ± 6.2 | 14.0 ± 7.5 | NS |

| Hospital stay (d) | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | NS |

| Wexner score | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.2 ± 1.4 | 5.0 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Size of specimen | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | NS |

| Margin(positive/negative) | 0/59 | 0/38 | 0/21 | NS |

| Invasion (M/SM/MP) | 26/16/5 | 22/11/5 | 4/5/01 | |

| Grade (G1/G2) | 35/12 | 28/10 | 7/21 | |

Nine specimens obtained by TEM had residual tumor. TEM: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery; M: Mucosa; S: Submucosa; MP: Muscularis propria; NS: Not significant.

Surgery

The full-thickness excisions using TEM were performed by the same surgical personnel. The mean surgical duration was 57.6 ± 13.7 min, the mean blood loss was 13.5 ± 6.6 mL, and all specimens were integrated. No severe immediate or late complications were noted. Perforation into the peritoneal cavity occurred in 2 patients (3.4%) without conversion to a transabdominal approach. There was no leakage of feces or intestinal juices into the peritoneal cavity because of good bowel preparation and prompt suturing. Moderate fever was observed in 8 patients (13.6%) within 3 d after the surgery, with a maximum body temperature of 38.2 °C, and was reduced without giving any antibiotics. Absorption fever might be the cause of the transient moderate fever. No complication of peritonitis, fistula, or fecal incontinence was observed during the hospital stay and follow-up period. Patients started walking on the first postoperative day, and per-oral intake on the second postoperative day. The mean hospital stay was 2.7 ± 1.0 d. The Wexner score at 6 mo was 4.5 ± 1.4.

Pathological data

All removed neoplasms in the primary excision group were diagnosed as typical neuroendocrine tumors. Among the 21 patients who underwent complete surgery after endoscopic polypectomy, 9 (42.9%) had a residual tumor in the mucosal or submucosal layer of the specimens obtained by TEM, but the remaining 12 patients had no histologic evidence of residual tumor. All vertical and lateral surgical margins of specimens were completely free of tumor cells, although 21 out of 59 tumors had developed outside the mucosal layer, with 5 infiltrating into the muscular layer.

Follow-up

No additional radical surgery was performed on these patients after TEM. They were followed up every 4 or 6 mo thereafter in the outpatient department. Computed tomography, transrectal endoscopy, and ultrasonography were performed. Of the 59 patients, follow-up data was collected for 53 cases. The median follow-up period was 3 years (range, 0.1-8.0 years). No recurrence, and no local or distant metastasis was observed.

DISCUSSION

A neuroendocrine tumor is a well-differentiated epithelial neoplasm with predominant neuroendocrine differentiation. It includes tumors previously classified as “carcinoid”, and rectifies its largely incorrect benign connotation. According to the World Health Organization 2010 classification, the neuroendocrine tumor could be classified as a grade G1 tumor [mitotic count < 2 per 10 high-power field (HPF) and/or Ki67 ≤ 2%] or a grade G2 tumor (mitotic count 2-20 per 10 HPF and/or Ki67 3%-20%)[4]. As the cellular atypia and the proliferative activity are low, a rectal neuroendocrine tumor generally has a favorable prognosis, with an overall 5-year survival rate of 88.3%[12]. The only guaranteed curative option is complete tumor resection[13].

Rectal neuroendocrine tumors larger than 2 cm, which are associated with significantly higher proliferative activity and metastatic risk (ranging between 60% and 80%)[14], are suitable candidates for radical surgery. Conventional anterior resection with total mesorectal excision or abdominoperineal extirpation could remove the local lesion and metastasis together when tumors display metastatic tendencies or for patients with any metastasis at diagnosis[4]. Meanwhile, multidisciplinary treatment options could be offered according to the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) Consensus Guidelines[4]. For most of the small and well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors, it is considered that radical surgery carries a higher risk-to-benefit ratio, and local resection is adequate. It is suggested that rectal neuroendocrine tumors that are 1 cm or less in size metastasize in only 3%-9.8% of cases[2,15], and local resection could provide complete resection. However, it may be difficult for conventional polypectomy used with virtual colonoscopy to obtain complete resection and achieve clear surgical margin, especially when the tumor is sessile or arises from the deep portion (Figure 3). As for rectal neuroendocrine tumors between 1 and 2 cm, the metastatic risk is considered to be between 10% and 15%[14]. Moreover, 76% of these tumors extend to the submucosal area[16], so local therapy using conventional endoscopic resection is a matter of debate[17,18].

TEM was developed by Buess et al[11] in Germany and was introduced into clinical practice in 1983. With a pressure-controlled gas (carbon dioxide) insufflator, an operating rectoscope (either 12 cm or 20 cm in length), and special long-handled surgical instruments for dissection, excision, and suturing, TEM is feasible for reaching tumors as much as 20 cm from the anal verge[3,13]. Our previous study proved that TEM could resect upper rectal neoplasms and be less invasive than traditional trans-anal or trans-sphincter approaches[19]. Moreover, the TEM procedure enables the accurate determination of surgical margins by marking the resection area with coagulation dots using a needle electrode before resection. Under a magnified visual view of up to 6-fold and a broadened operative field by carbon dioxide insufflations, tumor resection could be performed with safe surgical margins and an accurate surgical plane[20], and full-thickness suturing could be achieved (Figure 1).

Full-thickness excision using TEM is considered to provide complete resection of a local tumor without lymphatic or blood vessel invasion or lymph node metastases. As described in our report, although 35.6% of tumors developed outside the mucosal layer, the surgical margins of all specimens were negative. That indicates the effectiveness and accuracy of the full-thickness excision using TEM. No recurrence was found, and a cure rate of essentially 100% can be anticipated. Besides, 21 patients underwent complete resection after endoscopic polypectomy by gastroenterologists in other hospitals, because the margin of the specimen was identified as tumor positive. After full-thickness excision of lesions using TEM, 9 patients had microscopic evidence of residual tumors in the specimens obtained, and no complication or recurrence was found. Therefore, full-thickness excision using TEM can be an effective option for complete surgery. Localization using a tattoo or thread knot is strongly recommended during endoscopic polypectomy to facilitate full-thickness excision. If a mark was not applied at the time of snare polypectomy and the margins were found to be inadequate, the patient must be recalled urgently in order to identify the scar before it faded away[21,22].

Full-thickness excision using TEM is also a safe procedure. The morbidity of TEM was reported in the literature to be 4% to 29%[23,24], and the most common complications after TEM are bleeding, peritoneal entry, conversion to laparotomy, and fecal soiling[25]. Our data, in conjunction with the data presented by other surgeons, attest to full-thickness excision using TEM as being a very safe procedure[25,26]. The blood loss was about 15 mL, and electric coagulation and water rinsing could provide a clear surgical field. Entry into the peritoneal cavity during TEM was not considered as a complication and not associated with an increased risk of other complications[27]. With the possibility of suturing, rectal wall perforations which were considered as the most hazardous complication of local resection could also be tackled without conversion to laparotomy[28]. Achieving watertight intra-rectal repair of defects is crucial for preventing wound bleeding, peritonitis, and fistula[29]. No peritonitis, fistula, or fecal incontinence was observed in our study, and the Wexner score at 6 mo was 4.5 ± 1.4.

ENETS Consensus Guidelines suggested that a neuroendocrine tumor < 1 cm in diameter without muscularis invasion should have local resection endoscopically, with transanal mucosal-muscular resection using a variety of techniques and equipment for tumors < 1 cm with muscularis invasion, or for tumors between 1 and 2 cm without muscularis invasion[4]. In our study, the tumor of 12 patients in the completion group was < 1 cm in diameter and had no muscularis invasion. Endoscopic resection with many local transanal techniques (band-snare resection, aspiration lumpectomy) did not achieve a negative margin. Therefore, whether that type of endoscopic resection is suitable for these patients should be reconsidered, and full-thickness resection using TEM as the first surgical choice for these patients may be better. In addition, the guidelines did not give suggestions about tumors between 1 and 2 cm with muscularis invasion. We performed full-thickness excision of these tumors on 5 patients, and the surgical margins of all specimens were negative. Our experience is that for patients with neuroendocrine tumors < 2 cm without invasion of the lymph nodes or metastasis, full-thickness excision using TEM should be the preferred option. As TEM enables a much greater extent of resection, it ensures more satisfactory oncological results for lesions with malignant potential, and does not increase the complication rates.

With the clinical application of TEM for rectal neoplasms, several reports involving small case series have been published[30]. To the best of our knowledge, our report is the first and largest to describe the effectiveness of full-thickness excision of rectal neuroendocrine tumors using TEM in China. The largest series in the United States and Japan included 24 patients and 27 patients respectively, but they did not perform full-thickness excisions in all patients[11,21]. The retrospective design and lack of a comparative group are limitations of our study. Although evidence is limited, all the results showed that full-thickness excision using TEM could be a first surgical option for complete removal of rectal neuroendocrine tumors.

In conclusion, TEM is a safe, minimally invasive procedure, and full-thickness excision could achieve complete resection. Therefore, full-thickness excision using TEM could be a first surgical option for complete removal of higher rectal neuroendocrine tumors less than 2 cm.

COMMENTS

Background

The incidence of rectal neuroendocrine tumors is increasing quickly and steadily worldwide, and surgical removal of a single lesion is the only guaranteed curative option. With the introduction of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM), the clinical efficacy of TEM for benign neoplasm has been widely reported. Full-thickness excision using TEM enables a much greater extent of resection, ensuring more satisfactory oncological results for lesions with malignant potential. However, the application of TEM in full-thickness excision has not been well investigated.

Research frontiers

The TEM procedure provides several advantages over conventional excision by offering much improved visualization, exposure, and access to higher lesions in the rectum. Moreover, the TEM procedure could achieve accurate determination of margins and full-thickness excision with the possibility of suturing. The authors here report their clinical experiences of the largest cohort of patients with rectal neuroendocrine tumors treated by full-thickness excision using TEM.

Innovations and breakthroughs

With the clinical application of TEM for rectal neoplasms, several reports involving small case series have been published. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first and largest to describe the effectiveness of full-thickness excision of rectal neuroendocrine tumors using TEM in China. The largest series in the United States and Japan included 24 patients and 27 patients respectively, but they did not perform full-thickness excisions on all patients.

Applications

The study results suggest that full-thickness excision using TEM could be a first surgical option for complete removal of higher rectal neuroendocrine tumors less than 2 cm. TEM is a safe, minimally invasive procedure, and full-thickness excision could achieve complete resection.

Terminology

Neuroendocrine tumors are epithelial neoplasms with predominant neuroendocrine differentiation which occur in most organs of the body, and share common features, such as similar microscopic appearance, special secretory granules, and secretion of biogenic amines and polypeptide hormones. Many are benign, while some are malignant. TEM is an important application of minimally invasive surgery of the rectum. With a pressure-controlled gas (carbon dioxide) insufflator, an operating rectoscope (either 12 cm or 20 cm in length), and special long-handled surgical instruments, dissection, excision, and suturing could be achieved.

Peer-review

This manuscript analyzed a large number of patients with neuroendocrine tumor compared to the previous papers. Most reviewers found this topic interesting, informative and believed it to bring pleasure to the readers. The manuscript was praised for being well-written and structured.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Peking Union Medical College Hospital Review Board.

Informed consent statement: All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: No financial support or incentive has been provided for this manuscript. All authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Data sharing statement: We would share our technical appendix, statistical code, and dataset available from the corresponding author at [guolelin2002@163.com]. Participants gave informed consent for data.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: February 26, 2015

First decision: March 26, 2015

Article in press: May 7, 2015

P- Reviewer: Ji Y, Nomiya T, Su CH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Tsikitis VL, Wertheim BC, Guerrero MA. Trends of incidence and survival of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in the United States: a seer analysis. J Cancer. 2012;3:292–302. doi: 10.7150/jca.4502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scherübl H. Rectal carcinoids are on the rise: early detection by screening endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:162–165. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1119456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi HH, Kim JS, Cheung DY, Cho YS. Which endoscopic treatment is the best for small rectal carcinoid tumors? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:487–494. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i10.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caplin M, Sundin A, Nillson O, Baum RP, Klose KJ, Kelestimur F, Plöckinger U, Papotti M, Salazar R, Pascher A. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: colorectal neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:88–97. doi: 10.1159/000335594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okamoto Y, Fujii M, Tateiwa S, Sakai T, Ochi F, Sugano M, Oshiro K, Masai K, Okabayashi Y. Treatment of multiple rectal carcinoids by endoscopic mucosal resection using a device for esophageal variceal ligation. Endoscopy. 2004;36:469–470. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Son HJ, Sohn DK, Hong CW, Han KS, Kim BC, Park JW, Choi HS, Chang HJ, Oh JH. Factors associated with complete local excision of small rectal carcinoid tumor. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s00384-012-1538-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauven P, Ridge JA, Quan SH, Sigurdson ER. Anorectal carcinoid tumors. Is aggressive surgery warranted? Ann Surg. 1990;211:67–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199001000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeon SM, Cheon JH. Rectal carcinoid tumors: pitfalls of conventional polypectomy. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:2–3. doi: 10.5946/ce.2012.45.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maeda K, Maruta M, Utsumi T, Sato H, Masumori K, Matsumoto M. Minimally invasive surgery for carcinoid tumors in the rectum. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56 Suppl 1:222s–226s. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(02)00218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwaan MR, Goldberg JE, Bleday R. Rectal carcinoid tumors: review of results after endoscopic and surgical therapy. Arch Surg. 2008;143:471–475. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buess G, Theiss R, Hutterer F, Pichlmaier H, Pelz C, Holfeld T, Said S, Isselhard W. Transanal endoscopic surgery of the rectum - testing a new method in animal experiments. Leber Magen Darm. 1983;13:73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa K, Arita T, Shimoda K, Hagino Y, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Usefulness of transanal endoscopic surgery for carcinoid tumor in the upper and middle rectum. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1151–1154. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-2076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shields CJ, Tiret E, Winter DC. Carcinoid tumors of the rectum: a multi-institutional international collaboration. Ann Surg. 2010;252:750–755. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fb8df6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onozato Y, Kakizaki S, Iizuka H, Sohara N, Mori M, Itoh H. Endoscopic treatment of rectal carcinoid tumors. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:169–176. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b9db7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1587–1595. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsukamoto S, Fujita S, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto S, Akasu T, Moriya Y, Taniguchi H, Shimoda T. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of rectal well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:1109–1113. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherübl H. Comment on Ramage et al.: Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumours: well-differentiated colon and rectum tumour/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;88:157–158; author reply 158-159. doi: 10.1159/000158560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin GL, Meng WC, Lau PY, Qiu HZ, Yip AW. Local resection for early rectal tumours: Comparative study of transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) versus posterior trans-sphincteric approach (Mason’s operation) Asian J Surg. 2006;29:227–232. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demartines N, von Flüe MO, Harder FH. Transanal endoscopic microsurgical excision of rectal tumors: indications and results. World J Surg. 2001;25:870–875. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar AS, Sidani SM, Kolli K, Stahl TJ, Ayscue JM, Fitzgerald JF, Smith LE. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal carcinoids: the largest reported United States experience. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:562–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arolfo S, Allaix ME, Migliore M, Cravero F, Arezzo A, Morino M. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery after endoscopic resection of malignant rectal polyps: a useful technique for indication to radical treatment. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1136–1140. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3290-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HR, Lee WY, Jung KU, Chung HJ, Kim CJ, Yun HR, Cho YB, Yun SH, Kim HC, Chun HK. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the treatment of well-differentiated rectal neuroendocrine tumors. J Korean Soc Coloproctol. 2012;28:201–204. doi: 10.3393/jksc.2012.28.4.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serra-Aracil X, Mora-Lopez L, Alcantara-Moral M, Corredera-Cantarin C, Gomez-Diaz C, Navarro-Soto S. Atypical indications for transanal endoscopic microsurgery to avoid major surgery. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s10151-013-1040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar AS, Coralic J, Kelleher DC, Sidani S, Kolli K, Smith LE. Complications of transanal endoscopic microsurgery are rare and minor: a single institution’s analysis and comparison to existing data. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:295–300. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31827163f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flexer SM, Durham-Hall AC, Steward MA, Robinson JM. TEMS: results of a specialist centre. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1874–1878. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3407-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramwell A, Evans J, Bignell M, Mathias J, Simson J. The creation of a peritoneal defect in transanal endoscopic microsurgery does not increase complications. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:964–966. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allaix ME, Arezzo A, Caldart M, Festa F, Morino M. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal neoplasms: experience of 300 consecutive cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1831–1836. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b14d2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duek SD, Kluger Y, Grunner S, Weinbroum AA, Khoury W. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery for the resection of submucosal and retrorectal tumors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:66–68. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182757860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Léonard D, Colin JF, Remue C, Jamart J, Kartheuser A. Transanal endoscopic microsurgery: long-term experience, indication expansion, and technical improvements. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:312–322. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1869-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]