Abstract

Background

The thalamus occupies a pivotal position within the cortico-basal ganglia-cortical circuits. In Parkinson's disease, the thalamus exhibits pathological neuronal discharge patterns, foremost increased bursting and oscillatory activity, which are thought to perturb the faithful transfer of basal ganglia impulse flow to the cortex. Analogous abnormal thalamic discharge patterns develop in animals with experimentally reduced thalamic noradrenaline; conversely, added to thalamic neuronal preparations, noradrenaline exhibits marked anti-oscillatory and anti-bursting activity. Our study is based on this experimentally established link between noradrenaline and the quality of thalamic neuronal discharges.

Methods

We analysed fourteen thalamic nuclei from all functionally relevant territories of nine patients with Parkinson's disease and eight controls and measured noradrenaline with high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection.

Results

In Parkinson's disease, noradrenaline was profoundly reduced in all nuclei of the motor (pallidonigral and cerebellar) thalamus (ventroanterior: -86%, p=0.0011; ventrolateral oral: -87%, p=0.0010; ventrolateral caudal: -89%, p=0.0014): Also marked noradrenaline losses, ranging from 68% to 91% of controls, were found in other thalamic territories, including associative, limbic and intralaminar regions; the primary sensory regions were only mildly affected.

Conclusions

The marked noradrenergic deafferentiation of the thalamus discloses a strategically located noradrenergic component in the overall pathophysiology of the Parkinson's disease, suggesting a role in the complex mechanisms involved with the genesis of the motor and non-motor symptoms. Our study thus significantly contributes to the knowledge of the extrastriatal non-dopaminergic mechanisms of Parkinson's disease with direct relevance to treatment of this disorder.

Keywords: noradrenaline, Parkinson's disease, thalamic nuclei

Introduction

Although loss of the nigrostriatal dopamine is the indispensable feature of Parkinson's disease (PD) 1, 2, the fully developed clinical disorder cannot be explained solely by striatal dopamine loss; dopaminergic treatments do not correct all PD symptoms 3, thus pointing to some additional, likely extrastriatal mechanisms. Within the extrastriatal components of the cortico-basal ganglia-cortical circuits the thalamus occupies a central position for the transfer of the cortico-basal ganglia motor, associative and limbic information back onto the cortex 4-6. Directly relevant to PD, the motor ventroanterior and the oral ventrolateral thalamic nuclei are direct targets of the large internal globus pallidus/substantia nigra reticulata (Gpi/SNr) input which in turn, is under the influence of the striatum and the subthalamic nucleus via the “direct” (excitatory) and the “indirect” (inhibitory) pathways. Another motor input to the thalamus originates in the cerebellum and terminates in the caudal ventrolateral motor thalamic nucleus (for review, see ref.7, 8). The recently disclosed pathological neuronal discharge patterns, above all burst firing and increased oscillatory activity in the parkinsonian motor thalamus 7, point to some pathologic alterations affecting directly the functioning of the thalamic neuronal networks. The prevailing explanation, however, holds that these thalamic abnormalities are fully accounted for by the loss of the basal ganglia dopamine, resulting in an increased inhibitory drive of the Gpi/SNr pathway on the thalamic neuronal activity (see ref. 7). This dopamine- and striatocentric view totally neglects the possible role of defects in the dense neurotransmitter/neuromodulator inputs to the thalamus from the lower brain stem which have strong modulatory influence on thalamic neuronal activity - of which the noradrenergic input from the locus coeruleus is the most prominent.

Noradrenaline has distinct and marked electrophysiologic effects on the neuronal activity of the thalamus. In thalamic slice preparations, noradrenaline changes the characteristic burst firing and oscillations of the relay neurons (the thalamus is a well-known “oscillator”, 9, 10) to the single spike (the “transfer”) mode of firing 11, 12. Noradrenaline thus changes the highly non-linear output of the relay neurons (relative to their input) to a more one-to-one (“high fidelity”) signal transfer 13. This effect is brought about by noradrenaline abolishing the low threshold Ca2+ spike discharges typical of thalamic neurons, and reducing the hyperpolarization of the neuronal membranes thereby dampening the neuronal responses to large hyperpolarizing inputs 14 (cf. review 15). In the anesthetized animal (rat), noradrenaline, applied to neurons in the ventroposterior medial thalamus, amplifies the “signal-to-noise” ratio and focuses the receptive fields of neuronal ensembles 16. In the awake freely moving rat, noradrenaline via α1 receptors blocks indices of thalamic oscillatory activity, which, conversely, are pathologically increased by reduction of thalamic noradrenaline levels (with intrathalamic or intracisternal 6-hydroxydopamine) 17.

In PD, the neurodegenerative changes, not confined to the dopaminergic substantia nigra, also affect the noradrenergic locus coeruleus 18, suggesting brain noradrenaline involvement in this disorder (for review of the status of the noradrenergic brain systems in PD, see ref. 19). The similarity between the pathological thalamic neuronal discharges in experimental animals with noradrenaline-depleted thalamus (see above) and those occurring in several thalamic territories in patients with PD, suggests a common mechanism. Guided by this consideration, we sought to obtain biochemical evidence for the assumption that in PD the expected changes of thalamic noradrenaline 20 might be both sufficiently severe and localized to functionally relevant thalamic territories, so as to contribute to the genesis of the motor and non-motor symptoms of this disorder.

Materials and Methods

Autopsied brains were obtained from 9 neuropathologically confirmed PD and 8 control subjects without evidence in their records of any neurological or psychiatric disorder. Clinical, drug history and brain neuropathological findings of the patients with PD are shown in Table 1. Neither the mean ages (± SEM) of the control and PD patient groups (72.1 ± 2.6 yrs and 75.0 ± 2.0 years, respectively) nor the mean interval between death and freezing of the brain (controls; 11.8 ± 1.7 hrs; patients; 13.3 ± 2.0 hrs) did differ significantly. The causes of death for the control subjects were carcinoma (n=2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=1), embolism (n=1), renal failure (n=1), exsanguination (n=1), rupture of atherosclerotic aorta (n=1), and natural death (n=1).

Table 1. Clinically diagnosed Parkinson's disease – Patient information.

| Age (yrs) Gender | pm time (hours) | Pathology Cell loss/LB in | Duration of disease (yrs) | Cause of death | PD medication | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN | LC | ||||||

| 1 | 79 F | 15 | +/++/LB | +/++/LB | 18 | Aspiration bronchopneumonia | Sinemet |

| 2 | 77 F | 6 | demelanized/LB | demelanized/LB | 16 | Unknown | Sinemet |

| 3 | 81 F | 19 | ++/LB | - / - | 29 | Pulmonal embolism | Sinemet |

| 4 | 70 M | 11 | +++/LB | - /LB | 25 | Unknown | Sinemet |

| 5 | 79 M | 10 | +++/LB | +++/LB | many yrs | Pneumonia | Not known |

| 6 | 66 F | 18 | atrophy/LB | - / - | many yrs | Massive aspiration | Sinemet |

| 7 | 69 M | 18 | +++/LB | +++/LB | ? | Bronchopneumonia | No L-dopa |

| 8 | 71 F | 3.5 | +/++/LB | ++/LB | appr. 25 yrs | Pneumonia | Not known |

| 9 | 83 M | 19 | +/++/LB | ++/LB | appr. 18 yrs | Unknown | Sinemet, deprenyl |

Abbr.: F = female, M = male, LB = Lewy body, LC = locus ceruleus, SN = substantia nigra, pm time = post mortem time

Cell loss: +/++ mild to moderate, ++ moderate, +++ severe, - no information

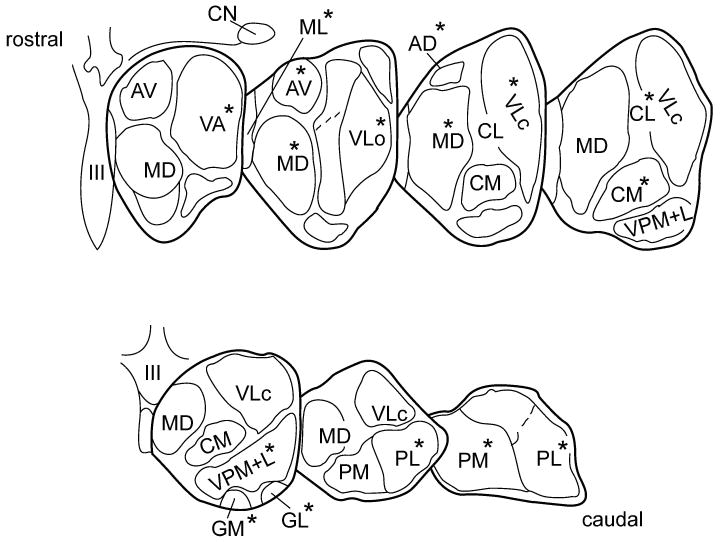

At autopsy, the brains were removed and divided into two half-brains (hemispheres) by a midsagittal section. The hemispheres to be used for neurochemical studies were immediately frozen at -80°C and kept at this temperature until dissection. They were then cut into coronal slices at a plane oriented at right angles to the long axis of the cerebral hemisphere21 on a glass plate kept on a bed of crushed dry ice. By this procedure, the whole of the rostro-caudal extension of the thalamus (approximately 30mm in length) was divided into 7 consecutive slices of approximately 4mm thickness each (Fig.1). In each thus dissected brain the thalamic slice no.4 was chosen as the reference slice, from which the intralaminar centromedian and centrolateral nuclei were taken for biochemical analyses; samples from all other nuclei were dissected from the three slices rostral and the three slices caudal to slice 4 respectively, as indicated in Fig.1. This standardized procedure allowed us to analyse, in each of the control and PD thalami, the same areas of the respective nuclei. The positions of the individual thalamic nuclei were identified according to the atlas of Riley21 with occasional help of the atlases in Crosby et al.22 and Carpenter23. The removed tissue samples were stored in tightly stoppered plastic vials at -80°C until analysis. The nomenclature for the dissected thalamic nuclei followed that used in Carpenter23.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic illustration showing the seven frontal slices, along the rostro-caudal axis, into which each of the control and PD thalami was divided. Delineated and labeled are those 14 nuclear regions from which tissue samples were dissected for noradrenaline analyses. The individual thalamic nuclei taken from a given slice are marked by an asterisk (*). Abbreviations: AD = anterodorsal; AV = anteroventral; CL = centrolateral; CM = centromedian; GL = lateral geniculate; GM = medial geniculate; MD = mediodorsal; ML midline (undivided); PL = lateral pulvinar; PM = medial pulvinar; VA = ventroanterior; VLo = ventrolateral oral; VLc = ventrolateral caudal; VPM+L = ventroposterior medial+lateral (combined). CN = caudate nucleus; III = third ventricle.

Noradrenaline and dopamine was determined by means of high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection as described previously24 with minor modifications: a LiChrospher 100 RP-18, 5μm column (LiChroCART®250-4, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), a programmable electrochemical detector 1049A at a potential of 0.55V (Hewlett Packard, Waldbronn, Germany) and a mobile phase containing 0.1M sodium phosphate, pH 4.9, 1mM EDTA, 0.5mM l-octane sulphonic acid and 9% methanol. The limits of detection, defined as a peak of at least the double the baseline noise, were 8 pg injected noradrenaline and 6 pg injected dopamine.

Semiquantitative assessment of neuronal loss in substantia nigra and locus coeruleus was accomplished using paraffin sections stained with haematoxylin-eosin/luxol fast blue and gliosis demonstrated with glial fibrillary acidic protein immunohistchemistry . Lewy bodies were detected by alpha-synuclein immunohistochemistry. Bielschowsky silver impregnation and tau immunohistochemistry were employed to highlight possible changes of Alzheimer's disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, or other tauopathies.

The results shown in Table 2 are the means ± SEM expressed in ng/g wet weight. Our pre-planned hypothesis was that mean thalamic noradrenaline levels would be decreased in the PD group as compared to those in the controls. Statistical difference between PD and control samples was calculated by two-tailed Student's t-test (as significantly different was considered p < 0.05). This study was approved by the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Research Ethics Board.

Table 2. Regional distribution of noradrenaline in human thalamus: Controls (A) vs. Parkinson's disease (B).

| Functional grouping of nuclear regions, and some of their putative functions1) | Individual nuclei analysed2) | Noradrenaline in ng/g wet weight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| A. Control (n = 8) | B. Parkinson (n = 9) | ||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| mean ± SEM | Range | mean ± SEM | range | % loss | P (vs. Control)3) | ||

| Motor: Motor movement, motor programs, complex behaviour | VA | 59.6 ± 9.9 | 24 – 103 | 8.5 ± 2.8 | 2 – 24 | -86% | 0.0011 |

| VLo | 104.4 ± 17.3 | 61 – 202 | 13.1 ± 3.7 | 2 – 31 | -87% | 0.0010 | |

| VLc | 150.5 ± 26.7 | 67 – 259 | 15.9 ± 3.9 | 2 – 33 | -89% | 0.0014 | |

| Limbic: Learning, memory, drive, emotional experience and expression | AV | 61.6 ± 20.1 | 7 – 183 | 5.4 ± 1.5 | 1 – 13 | -91% | 0.02674 |

| AD | 40.2 ± 5.3 | 19 – 56 | 9.0 ± 2.7 | 2 – 26 | -78% | 0.00033 | |

| Associative: Drive, motivation, executive function, working memory | MD | 164.4 ± 28.2 | 69 – 299 | 27.2 ± 7.5 | 1 – 60 | -84% | 0.00154 |

| - High supramodal associative | PL | 88.0 ± 14.0 | 18 – 146 | 11.7 ± 2.1 | 1 – 22 | -87% | 0.00089 |

| - Somatosensory, visual attention | PM | 86.9 ± 13.8 | 34 – 153 | 22.7 ± 4.2 | 6 – 46 | -74% | 0.00197 |

| Intralaminar/Midline: Arousal, motivation, attention, affective components of pain | CM | 312.0 ± 38.6 | 184 – 467 | 63.2 ± 29.8 | 5 – 283 | -80% | 0.00018 |

| CL | 160.1 ± 23.8 | 28 – 257 | 51.4 ± 16.2 | 2 – 137 | -68% | 0.00241 | |

| ML | 256.0 ± 73.3 | 59 – 650 | 60.3 ± 23.1 | 7 – 219 | -76% | 0.03316 | |

| Primary sensory: Processing of somatosensory, gustatory, vestibular information | VPM+L | 210.5 ± 24.4 | 121 – 330 | 95.1 ± 22.4 | 9 – 192 | -55% | 0.00343 |

| - Visual information | GM | 65.3 ± 10.0 | 27 – 93 | 38.2 ± 13.5 | 7 – 108 | -42% | 0.12991 |

| - Auditory information | GL | 13.2 ± 4.1 | 2 – 36 | 5.2 ± 1.1 | 2 – 12 | -66% | 0.10270 |

Results

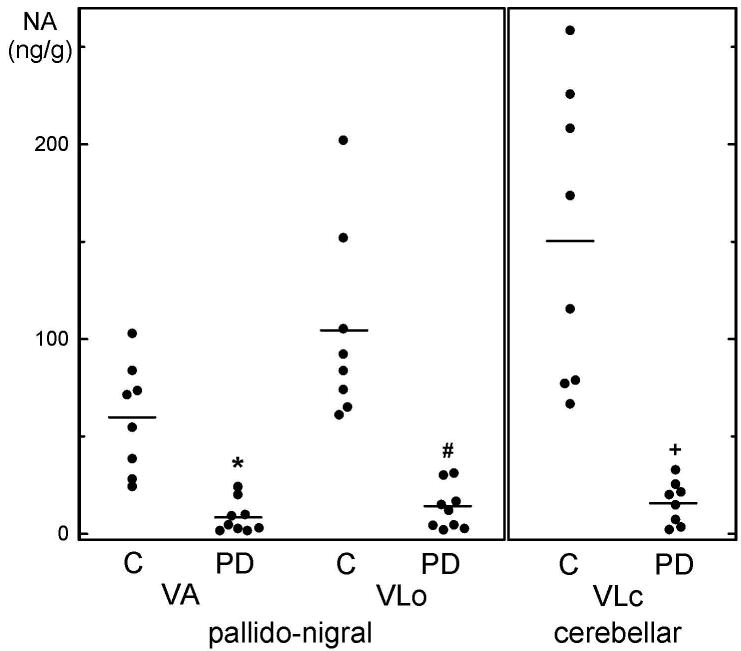

The 14 regions included in this study were taken from all functionally defined territories of the control and PD thalamus. As shown in Table 2 (mean noradrenaline levels ± s.e.m. and ranges) and Figure 2 (single values), no region of the human thalamus was devoid of noradrenaline, and none was completely spared from noradrenaline loss in PD.

Figure 2.

Individual values of noradrenaline (circles) and mean values (horizontal lines) in the ventroanterior (VA) and ventrolateral oral (VLo) nuclear group of the pallido-nigral and the ventrolateral caudal (VLc) nuclear group of the cerebellar motor thalamus of 8 control subjects (C) and 9 patients with Parkinson's disease (PD). * P=0.001072, # P=0.000997, + P=0.001409 by two-tailed Student's t-test.

In the control thalamus, the distribution pattern of noradrenaline was uneven (cf. Table 2A), ranging from less than 90 ng/g mean values in both the rostral and caudal portions to comparatively high levels ( ≥ 300 ng/g) in nuclei situated in the main body of the thalamic mass, where some individual noradrenaline levels reached one third to one half of the amine concentrations reported for the human postmortem hypothalamus25. The scatter of the individual noradrenaline levels within each thalamic nucleus, although considerable, ranged in most nuclei between 2.5-fold to 11-fold which is not greater than that observed in postmortem material for dopamine or serotonin in caudate and/or putamen26.

Specifically, within the group of the motor thalamic nuclei – regions of primary importance for PD as a motor disorder - in our control group, the distribution of noradrenaline varied considerably. Thus, the ventroanterior nucleus contained 59.6 ng/g noradrenaline, the ventrolateral oral 104.4 ng/g, and the ventrolateral caudal as much as 150.5 ng/g. In PD, all three motor nuclei suffered very severe noradrenaline losses (Table 2B), ranging between 86% and close to 90% loss. As shown in Figure 2, the single case noradrenaline values in the PD group did not overlap with any of the control values, conferring disease specificity on this alteration.

In the limbic anteroventral and anterodorasal nuclei, control noradrenaline levels were in the low range (62 ng/g and 40 ng/g, respectively). In PD, the noradrenaline loss was very severe in the former (91% loss), and somewhat less marked in the anterodorsal nucleus (78% loss).

In the associative nuclear group, the functionally prominent mediodorsal nucleus had intermediate control noradrenaline levels (164 ng/g), with the likewise associative lateral and medial pulvinar having 88 ng/g and 87 ng/g noradrenaline. In PD, a profound loss of noradrenaline was measured in both the mediodorsal nucleus (84% loss; not overlapping with controls!) and the lateral pulvinar (87% loss), with the losses in the medial pulvinar reaching the 74% mark.

The highest mean control noradrenaline levels measured in the human thalamus, 312 ng/g, were observed in the intralaminar centromedian nucleus, which not only has strong reciprocal connections with the basal ganglia, especially the PD-related putamen27, but also is affected by significant cell loss in PD28. The centrolateral nuclear region, also interlaminar, contained 160 ng/g, and the midline nuclear region, 256 ng/g noradrenaline. In PD, the loss of noradrenaline was profound in the centromedian nucleus (80% loss), with lesser losses in the midline (76% loss) and centrolateral (68% loss) nuclear regions.

The group of the primary sensory nuclei exhibited particularly high internuclear differences. Whereas the ventroposterior (lateral+medial) nucleus had noradrenaline in the high range (211 ng/g mean value), the medial geniculate nucleus had 65 ng/g and the lateral geniculate only 13 ng/g noradrenaline. In PD, these nuclei, in contrast to the rest of the thalamic nuclei, suffered only mild losses of noradrenaline: 66% loss in the lateral geniculate; 55% loss in the ventroposterior lateral+medial; and 42%, noradrenaline loss in the medial geniculate.

Except for the two geniculate nuclei, the loss of noradrenaline in all other thalamic nuclei analyzed in this study was statistically significant (Table 2, Student's two-tailed t-test).

Discussion

The nuclear distribution pattern of noradrenaline in the thalamus of our control subjects is in general agreement with the noradrenaline values provided in the thalamic “grid” distribution study of Oke et al.29, in which, however, the authors did not attempt to dissect and analyze individual thalamic nuclei.

This is the first systematic study of subregional noradrenaline patterns in functionally distinct thalamic territories of patients with PD. Our major finding is a marked to severe reduction of noradrenaline in most nuclear regions of the parkinsonian thalamus, with only the primary sensory regions having milder noradrenaline deficits. This widespread loss of thalamic noradrenaline in PD can be taken as being the result of the well-established degeneration of the melanin-containing noradrenergic neurons of the locus coeruleus 18 which supply the substantial noradrenergic innervation to most of the thalamic nuclei 30. The magnitude of the noradrenaline reduction in the majority of thalamic nuclei analysed fell within the extent of reduction in the same patients of dopamine in caudate (-77%) and putamen (-97%). However, there was no correlation between the dopamine loss in caudate or putamen and the noradrenaline loss in thalamic motor nuclei emphasizing the functionally distinct role of thalamic noradrenaline in PD. In contrast to the substantial loss of noradrenaline, the thalamic dopamine levels, besides being in the human only a fraction of noradrenaline 29, havebeen previously shown to be in PD not significantly different from controls 31.

What might be the significance of our observations for PD as a motor disorder? The near complete (by more than 85%) loss of motor thalamic noradrenaline will, with high probability, result in loss of noradrenaline's physiologic, experimentally established 14 influence on the functioning of thalamic neurons. Accordingly, because lack of noradrenaline reduces the efficacy and accuracy of thalamic information processing (high background noise; decreased specificity of the neuronal receptive fields; pathologically increased neuronal burst firing and oscillatory activity 16, 17), in the PD thalamus the overall quality of signal transfer can be expected to be significantly reduced, especially so in its motor subdivision. This appears to be indeed the case. Thus in the MPTP parkinsonian monkey, a marked decrease in the specificity of the receptive fields has been observed in the motor thalamus 32 and increased neuronal bursting and appearence of pathological oscillatory activity and synchrony in the motor thalamus (as in the other components of the basal ganglia-cortical circuitry) has now been recognized as one of the fundamental pathophysiologic abnormalities in PD 7, 33-35. The thalamic oscillations in the PD patient may have the characteristics of low-threshold Ca2+ spikes 36, 37 (but see ref. 38, 39) which in thalamic slice preparations are abolished by noradrenaline 14. This possible link to noradrenaline may be of some consequence, also for our observations; thus, the motor thalamic oscillations, besides being associated with the parkinsonian tremor, may also, according to Magnin et al. 37, play a part, via the thalamocortical connections with the supplementary and presupplementary motor areas, in the genesis of the symptoms of bradykinesia and rigidity. Also relevant to our noradrenaline findings (see below) appear observations indicating that some aspects of thalamic sensory processing, such as the thalamic receptive fields' specificity (which is sensitive to noradrenergic modulation 16) is lost, in the progressive MPTP primate, prior to development of the motor symptoms 32. Considered together, the loss of thalamic noradrenaline, which was especially massive and consistent in the motor nuclei of our PD patients, suggests itself as an important participant in the complex mechanisms of these pathophysiologic phenomena.

In the PD group the marked loss of thalamic noradrenaline was wide-spread, affecting, in addition to the motor thalamus, several associative, limbic, and intralaminar/midline nuclear groups (Table 2B). This suggests that, if the proposed interpretation of our data is correct, the perturbance of the thalamocortical information processing may be wide-spread in PD, especially in the functionally prominent associative mediodorsal (not overlapping with controls) and pulvinar, as well as the limbic anteroventral nuclei (see Table 2). Is there any indication of this from clinical observations? Although PD is traditionally considered as a disorder of movement, recently increasing attention is being paid to the non-motor symptoms, which in the majority of patients accompany, or even precede, the motor disorder; these include, besides autonomic disturbances: apathy, loss of drive and motivation, and several higher brain dysfunctions, such as cognitive, executive and memory impairments, mood changes, anxiety, depressive states, and dementia 40. To us, several components of the non-motor symptoms resemble disturbances also manifested (although mostly transiently) by patients with strokes of functionally distinct thalamic territories 41. Many of the affected brain functions implicated in these symptoms, in particular those requiring heightened states of wakefulness, arousal, attention, and cognition, are indeed subserved by the locus coeruleus noradrenergic forebrain systems 42-48; for reviews see ref. 15, 49, 50; thus, loss of noradrenaline of the magnitude found in our PD patients, at the level of the respective thalamic nuclei, may play a considerable role in the genesis of these notoriously difficult to treat disturbances in PD.

Apart from limitations inherent in work with human post-mortem brain material, the major limitation of our study was the lack of clinical patient information that would have permitted us to correlate the post-mortem noradrenaline data with behavioural measures in the patients and determine whether the loss of thalamic noradrenaline was an early or late event in the course of the illness. In principle, this could be explored in brain imaging studies once a suitable radiolabelled probe assessing noradrenaline neuron integrity becomes available. Further, it has been proposed that some of the noradrenergic locus ceruleus fibres innervate the brain's intraparenchymal blood vessels (arterioles and capillaries51, for review see ref.52). In principle, loss of this noradrenaline in PD thalamus might exaggerate, through changes in permeability and blood flow53, the neuronal dysfunction caused by the 1oss of noradrenergic innervation to the thalamic neuronal elements proper. Our study does not allow to decide about the importance for PD of this particular aspect of locus ceruleus pathophysiology.

In conclusion, this study has two clinically highly relevant aspects. First, the high deficits of noradrenaline throughout most of the PD thalamus, a brain centre whose role in the pathophysiology of the parkinsonian disorder is firmly established, furnishes a plausible anatomical-pathochemical substrate for some of the extrastriatal, non-dopaminergic motor and non-motor disturbances in patients with PD. Second, the translational nature of this study confers on our observations direct drug-therapeutic relevance. Following the early clinical reports on the effectiveness of dopamine substitution with L-dopa 54, 55 (for historical retrospective, see ref. 56), noradrenaline – like dopamine formed in brain from L-dopa 57 – was proposed to play a role in PD (for review, see ref. 19), possibly explaining L-dopa's “magic” therapeutic effects (for discussion see ref. 58), which clearly surpass mere dopamine replacement with the direct acting dopamine agonists 59. By identifying a particular centre, the thalamus, as the specific site of the noradrenergic pathology in PD, our study provides, for the first time, a rational functional basis for the development of new chemical agents with high potential for restoring, besides the basal ganglia dopamine, the thalamic noradrenaline function largely lost in PD. It can not be excluded that this goal is already realized in the L-dopa molecule. However, the noradrenaline yield from L-dopa is only moderate 57. This suggests that there is sufficient rationale for improvement based on our study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joseph Gilbert, Mark Guttman, Manfred D. Muenter and Ali H. Rajput for the brain material and Harald Reither for technical assistance with noradrenaline analysis.

Funding: Part of this study was supported by US NIH NIDA DA29056 to SJK.

Footnotes

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosure: nothing to report.

Author Roles: C.P. performed noradrenaline analyses and analysed the data, S.J.K collected and dissected the brain material and identified the thalamic territories, O.H. designed the study, interpreted the results and wrote the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on text of the manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O. Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system. Klin Wochenschr. 1960;38:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/BF01485901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornykiewicz O. Biochemical aspects of Parkinson's disease. Neurology. 1998;51(2 Suppl 2):S2–S9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2_suppl_2.s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barone P. Neurotransmission in Parkinson's disease: beyond dopamine. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(3):364–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evarts EV, Kimura M, Wurtz RH, Hikosaka O. Behavioral correlates of activity in basal ganglia neurons. Trends in Neurosciences. 1984;7(11):447–453. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of basal ganglia disorders. Trends Neurosci. 1989;12(10):366–375. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galvan A, Wichmann T. Pathophysiology of parkinsonism. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119(7):1459–1474. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obeso JA, Marin C, Rodriguez-Oroz C, et al. The basal ganglia in Parkinson's disease: current concepts and unexplained observations. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(Suppl 2):S30–S46. doi: 10.1002/ana.21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jahnsen H, Llinas R. Electrophysiological properties of guinea-pig thalamic neurones: an in vitro study. J Physiol. 1984;349:205–226. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steriade M, Deschenes M. The thalamus as a neuronal oscillator. Brain Res. 1984;320(1):1–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pape HC, McCormick DA. Noradrenaline and serotonin selectively modulate thalamic burst firing by enhancing a hyperpolarization-activated cation current. Nature. 1989;340(6236):715–718. doi: 10.1038/340715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KH, McCormick DA. Abolition of spindle oscillations by serotonin and norepinephrine in the ferret lateral geniculate and perigeniculate nuclei in vitro. Neuron. 1996;17(2):309–321. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCormick DA, Feeser HR. Functional implications of burst firing and single spike activity in lateral geniculate relay neurons. Neuroscience. 1990;39(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90225-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCormick DA, Pape HC, Williamson A. Actions of norepinephrine in the cerebral cortex and thalamus: implications for function of the central noradrenergic system. Prog Brain Res. 1991;88:293–305. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63817-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42(1):33–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hirata A, Aguilar J, Castro-Alamancos MA. Noradrenergic activation amplifies bottom-up and top-down signal-to-noise ratios in sensory thalamus. J Neurosci. 2006;26(16):4426–4436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5298-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buzsaki G, Kennedy B, Solt VB, Ziegler M. Noradrenergic Control of Thalamic Oscillation: the Role of alpha-2 Receptors. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3(3):222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarow C, Lyness SA, Mortimer JA, Chui HC. Neuronal loss is greater in the locus coeruleus than nucleus basalis and substantia nigra in Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(3):337–341. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaville C, Deurwaerdere PD, Benazzouz A. Noradrenaline and Parkinson's disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:31. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farley IJ, Hornykiewicz O. Noradrenaline in subcortical brain regions in patients with Parkinson's disease and control subjects. In: Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O, editors. Advances In Parkinsonism. Basle: Editiones Roche; 1976. pp. 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley HA. An Atlas of the Basal Ganglia, Brain Stem and the Spinal Cord. New York: Hafner; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crosby EC, Humphery T, Lauer EW. Correlative Anatomy of the Nervous System. New York: Macmillan; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carpenter MB. Human Neuroanatomy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Company; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pifl C, Schingnitz G, Hornykiewicz O. Effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine on the regional distribution of brain monoamines in the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 1991;44(3):591–605. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannak K, Rajput A, Rozdilsky B, Kish S, Gilbert J, Hornykiewicz O. Noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin levels and metabolism in the human hypothalamus: observations in Parkinson's disease and normal subjects. Brain Res. 1994;639(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91761-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kish SJ, Tong J, Hornykiewicz O, et al. Preferential loss of serotonin markers in caudate versus putamen in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 1):120–131. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith Y, Raju D, Nanda B, Pare JF, Galvan A, Wichmann T. The thalamostriatal systems: anatomical and functional organization in normal and parkinsonian states. Brain Res Bull. 2009;78(2-3):60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henderson JM, Carpenter K, Cartwright H, Halliday GM. Degeneration of the centre median-parafascicular complex in Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;47(3):345–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oke AF, Carver LA, Gouvion CM, Adams RN. Three-dimensional mapping of norepinephrine and serotonin in human thalamus. Brain Res. 1997;763(1):69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00404-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindvall O, Bjorklund A, Nobin A, Stenevi U. The adrenergic innervation of the rat thalamus as revealed by the glyoxylic acid fluorescence method. J Comp Neurol. 1974;154(3):317–347. doi: 10.1002/cne.901540307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerlach M, Gsell W, Kornhuber J, et al. A post mortem study on neurochemical markers of dopaminergic, GABA-ergic and glutamatergic neurons in basal ganglia-thalamocortical circuits in Parkinson syndrome. Brain Res. 1996;741(1-2):142–152. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)00915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pessiglione M, Guehl D, Rolland AS, et al. Thalamic neuronal activity in dopamine-depleted primates: evidence for a loss of functional segregation within basal ganglia circuits. J Neurosci. 2005;25(6):1523–1531. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4056-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivlin-Etzion M, Marmor O, Heimer G, Raz A, Nini A, Bergman H. Basal ganglia oscillations and pathophysiology of movement disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16(6):629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown P. Oscillatory nature of human basal ganglia activity: relationship to the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2003;18(4):357–363. doi: 10.1002/mds.10358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammond C, Bergman H, Brown P. Pathological synchronization in Parkinson's disease: networks, models and treatments. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30(7):357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaneoke Y, Vitek J. The motor thalamus in the Parkinsonian primate: Enhanced burst and oscillatory activities. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 1995;21(1-3):1428. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magnin M, Morel A, Jeanmonod D. Single-unit analysis of the pallidum, thalamus and subthalamic nucleus in parkinsonian patients. Neuroscience. 2000;96(3):549–564. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zirh TA, Lenz FA, Reich SG, Dougherty PM. Patterns of bursting occurring in thalamic cells during parkinsonian tremor. Neuroscience. 1998;83(1):107–121. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molnar GF, Pilliar A, Lozano AM, Dostrovsky JO. Differences in neuronal firing rates in pallidal and cerebellar receiving areas of thalamus in patients with Parkinson's disease, essential tremor, and pain. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93(6):3094–3101. doi: 10.1152/jn.00881.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poewe W. Non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(Suppl 1):14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmahmann JD. Vascular syndromes of the thalamus. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2264–2278. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000087786.38997.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Foote SL, Bloom FE, ston-Jones G. Nucleus locus ceruleus: new evidence of anatomical and physiological specificity. Physiol Rev. 1983;63(3):844–914. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.3.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, ston-Jones G. Locus coeruleus activity in monkey: phasic and tonic changes are associated with altered vigilance. Brain Res Bull. 1994;35(5-6):607–616. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)90175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Usher M, Cohen JD, Servan-Schreiber D, Rajkowski J, Aston-Jones G. The role of locus coeruleus in the regulation of cognitive performance. Science. 1999;283(5401):549–554. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5401.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.LaBerge D, Buchsbaum MS. Positron emission tomographic measurements of pulvinar activity during an attention task. J Neurosci. 1990;10(2):613–619. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-02-00613.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frith CD, Friston KJ. The role of the thalamus in “top down” modulation of attention to sound. Neuroimage. 1996;4(3 Pt 1):210–215. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1996.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Portas CM, Rees G, Howseman AM, Josephs O, Turner R, Frith CD. A specific role for the thalamus in mediating the interaction of attention and arousal in humans. J Neurosci. 1998;18(21):8979–8989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08979.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coull JT, Jones ME, Egan TD, Frith CD, Maze M. Attentional effects of noradrenaline vary with arousal level: selective activation of thalamic pulvinar in humans. Neuroimage. 2004;22(1):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Central norepinephrine neurons and behavior. New York: Raven Press, Ltd.; 1995. Psychopharmacology: The fourth generation of progress. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sara SJ. The locus coeruleus and noradrenergic modulation of cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(3):211–223. doi: 10.1038/nrn2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hartman BK, Zide D, Udenfriend S. The use of dopamine -hydroxylase as a marker for the central noradrenergic nervous system in rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69(9):2722–2726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.9.2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandor P. Nervous control of the cerebrovascular system: doubts and facts. Neurochem Int. 1999;35(3):237–259. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raichle ME, Hartman BK, Eichling JO, Sharpe LG. Central noradrenergic regulation of cerebral blood flow and vascular permeability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72(9):3726–3730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.9.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O. The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1961;73:787–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cotzias GC, Van Woert MH, Schiffer LM. Aromatic amino acids and modification of parkinsonism. N Engl J Med. 1967;276(7):374–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196702162760703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Young AB. Four decades of neurodegenerative disease research: how far we have come! J Neurosci. 2009;29(41):12722–12728. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3767-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chalmers JP, Baldessarini RJ, Wurtman RJ. Effects of L-dopa on norepinephrine metabolism in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68(3):662–666. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.3.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mercuri NB, Bernardi G. The ‘magic’ of L-dopa: why is it the gold standard Parkinson's disease therapy? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26(7):341–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schapira AH, Emre M, Jenner P, Poewe W. Levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16(9):982–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]