Abstract

The aim of the present study was to investigate the clinical efficacy and safety of low-dose 90Sr-90Y therapy combined with the topical application of 0.5% timolol maleate solution for the treatment of superficial infantile hemangiomas (IHs). A total of 72 infants with hemangiomas were allocated at random into the observation group (17 cases aged ≤3 months, 20 cases aged >3 months) or the control group (15 cases aged ≤3 months, 20 cases aged >3 months). The observation group was treated with low-dose 90Sr-90Y combined with timolol, while the control group received an identical dose of 90Sr-90Y with physiological saline. Data were collected for statistical analysis, and treatment efficacy was compared between the two groups. In the observation group, 100% (37/37) of subjects exhibited an ‘excellent’ response to the treatment, while 94.1% (16/17) of patients aged ≤3 months and 85.0% (17/20) aged >3 months were classed as being cured. In the control group, the treatment was classed as ‘effective’ in 100% (35/35) of the subjects, while the excellent response rate was 86.7% (13/15) among the infants aged ≤3 months and 75.0% (15/20) among the infants aged >3 months. The ‘cure’ rates in the control group were 66.7% (10/15) and 60.0% (12/20) for the ≤3-month- and >3-month-old subjects, respectively. The excellent response and cure rates were notably higher in the observation group than those in the control group. Comparison between the two groups revealed a χ2 value of 13.90 (P<0.01) for excellent responses in subjects aged ≤3 months, while for patients aged >3 months the χ2 value was 28.57 (P<0.01). Analysis of the cure responses gave similar results [≤3 months, χ2=23.22 (P<0.01); >3 months, χ2=15.67 (P<0.01)]. At 3–4 months after the first course of treatment, the cure rate was 33.3% (11/33) in the observation group, which was significantly higher than the rate of 18.32% (4/22) in the control group (χ2=5.92, P<0.05). No serious adverse reactions were observed in either group. In summary, low-dose 90Sr-90Y therapy combined with the topical application of 0.5% timolol maleate induces a rapid response in superficial IH, with excellent efficacy and no obvious adverse reactions, and may represent a clinically applicable intervention.

Keywords: 90Sr-90Y application, low dose, timolol maleate, superficial infantile hemangioma, topical

Introduction

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common benign tumor of the skin in infants. The incidence rate of IH in premature or low birth weight infants is ≤22%, with an increased prevalence among female infants (~3–5:1, female to male). The life cycle of IH consists of three stages: Proliferating, involuting and involuted. The proliferating stage continues for a number of weeks prior to the involuting or involuted stages. The proliferating phase is characterized by the presence of small collections of primitive cells. The stimulus that promotes this growth is unknown. There are a number of characteristic endothelial markers of the early proliferating phase, including CD31 and Von Willebrand factor. Furthermore, other factors have been associated with IH growth in the later proliferating phase, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). All of these factors are plausible mechanisms underlying IH proliferation. IH is divided into three clinical types: Superficial, deep and mixed. Among these types, superficial IH predominantly occurs on the skin surface of the head, face and neck, followed by the limbs and trunk. Traditionally, the standard treatment for superficial or small-area hemangiomas was to observe the afflicted area and wait for spontaneous regression; however, certain superficial hemangiomas are large and the tumors often exhibit rapid growth at 6 months (1,2). Failure to conduct early intervention may lead to later treatment difficulty, prolong disease duration and ultimately result in facial defects or dysfunction. There are currently numerous methods for treating skin hemangioma; however, these continue to exhibit problems. Among the most effective treatment options for IH is the application of 90Sr-90Y radiation. Topical timolol maleate represent novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of IH, encouraging selection since it was first used in 2010 (3,4). In the present study, 90Sr-90Y radiation was combined with topically applied timolol to treat patients with IH between September 2012 and December 2013, in order to determine the value and clinical safety of the combination therapy.

Patients and methods

Patients

In total, 72 patients with IH were recruited from the 94th Hospital of PLA (Nanchang, China) between September 2012 and December 2013. The patients exhibited no serious heart, lung, liver or kidney diseases. IH was diagnosed according to the following criteria: i) Initial manifestation between a few days and 1 month after birth, with red punctate or patchy areas that were visible to the naked eye and that exhibited varying degrees of growth; ii) a subcutaneous hemangioma thickness of <3 mm, with no obvious blood flow signal and no arteriovenous malformation on color Doppler ultrasound; and iii) exclusion of other skin diseases following dermatological examination.

The 72 infants were allocated at random into the observation or control group. The observation group contained 15 males and 22 females, with ages ranging between 1 and 7 months (mean age, 3.8 months). Among the observation subjects, 17 cases were ≤3 months of age, while 20 cases were >3 months of age. The distribution of IH lesions consisted of 14 cases in the head, 10 cases in the face and 13 cases in the limbs and trunk. The tumor areas ranged between 0.8×0.7 and 18.6×8.0 cm, with 31 cases of single IH and 6 cases of multiple IH lesions. The control group consisted of 13 male and 22 female patients, with ages ranging between 1 and 7 months (mean age, 3.7 months). Among the control subjects, 15 cases were ≤3 months of age and the remaining 20 cases were >3 months old. The distribution of the vascular tumors was as follows: 16 cases in the head and face, 8 cases in the limbs and 11 cases in the trunk. The tumor area ranged between 0.8×1.0 and 15.0×6.3 cm, with 28 cases of single IH and 7 cases of multiple IH. The demographic data of the two groups of infants can be summarized as follows: Age ≤3 months, t=0.193 (P>0.05); age >3 months, t=0.611 (P>0.05); gender, χ2=0.087 (P>0.05); vascular tumor area, t=0.652 (P>0.05); lesion location, χ2=0.467 (P>0.05); and lesion count, χ2=0.174 (P>0.05). No statistically significant differences were observed in the patient demographics between the two groups. Treatments were approved by the hospital ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the guardians of each patient.

Treatment methods

The observation group received 1–2 courses of 90Sr-90Y contact therapy and local external application of 0.5% topical timolol solution (Wujing Medicine Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) on the affected area for 3–6 months. Control group patients received an identical dosage and treatment course of 90Sr-90Y contact therapy, combined with local topical application of normal saline (NS) for 3–6 months.

The 90Sr-90Y applicator was produced by Atomic Gaoke Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) with an applicator area of 2×2 cm and a surface-absorbed dose rate of 2.2 Gy/min. While in use, the active surface of the applicator was positioned on the surface of the hemangioma. If the tumor diameter was larger than the effective diameter of the 90Sr-90Y applicator, the tumor area was divided into a number of squares of the same size as the applicator, and the radiation therapy was then administered gradually (i.e. uniform irradiation) in order to ensure the correct dose of radiation exposure was received by the patient. Thick rubber (4–5 mm) was used to shield the normal skin surrounding the tumor. For the treatment of rapidly growing hemangiomas, the treatment area was extended to 0.5–1.0 cm beyond the edge of the tumor. The application of 90Sr-90Y radiation was conducted following the protocol described in a previous publication by the Chinese Medical Association (5); however, the dose of 90Sr-90Y was reduced to 10–12 Gy per treatment course. In cases with a total hemangioma area of <20 cm2, a single course of treatment consisted of a radiation dose of 2–2.4 Gy, once per day, for 5 consecutive days. In cases with a total hemangioma area of >20 cm2, a single course of treatment consisted of a radiation dose of 1–1.2 Gy, once per day, for 10 consecutive days. In the observation group, 0.5% timolol eye drops were applied evenly to the hemangioma surface at a dosage of 30 µl/cm2 each morning and night (6). The hemangioma surface was divided into a grid of 1×2-cm squares. Each region received a single 60-µl drop of 0.5% timolol solution, which was gently smeared over the area by finger for 5–10 sec until the solution was absorbed. Certain patients exhibited local ‘mild flaking’ following the administration of the timolol drops, which subsided after treatment was temporarily discontinued for 3–5 days. The control group received an identical dose of NS on the hemangioma surface. The two groups of patients were observed every month, and alterations in the color, size and texture of the hemangiomas were recorded. In cases in which the tumor was observed to be healing or to have significantly subsided, treatment was suspended, but regular follow-up continued. In all other cases, a second course of treatment was administered 3 months after the first, but the number of treatment courses did not exceed 2. The total dose administered prior to the termination of treatment was <24 Gy, while the total dose in sensitive areas, such as the lips, eyelids, orbital cavity and head, did not exceed 15 Gy.

Evaluation of efficacy and adverse reactions

Treatment efficacy criteria

The criteria for treatment efficacy were as follows (7): ‘Cure’, the hemangioma subsided completely and the skin returned to normal or exhibited barely visible discoloration; ‘excellent’, the color of the hemangioma faded significantly or the tumor size was reduced by more than two-thirds; ‘effective’, the hemangioma color faded or the tumor size was reduced by more than one-third; and ‘invalid’, the appearance of the hemangioma following treatment exhibited no significant alteration or the tumor continued to grow. The treatment response rates were calculated using the following equations: Effective response rate (%) = (cure cases + excellent cases + effective cases)/total number of cases × 100; excellent response rate (%) = (cure cases + excellent cases)/total number of cases × 100; cure response rate (%) = (cure cases)/total number of cases × 100.

Adverse reactions

Potential adverse reactions associated with the 90Sr-90Y radiation treatment include paresthesia (itching, burning, pain), pigmentation (mild pigmentation, lasting 2–3 months) or depigmentation, skin atrophy, dry radioactive dermatitis (erythema, rough, dry skin with fine scales) and wet radioactive dermatitis (skin edema, blisters, ulceration and infiltration, infection) (7).

In order to evaluate the adverse drug reactions, blood, liver, kidney, fasting blood glucose and electrocardiogram (ECG) data were collected from the two groups prior to and following treatment each month. In the observation group, breathing rate, heart rate, diet, stool quality and sleep behavior were recorded within 6 h after the 0.5% timolol solution administration. If adverse reactions were detected, the patients were administered the corresponding symptomatic treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Count data rates were compared using the χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Treatment efficacy

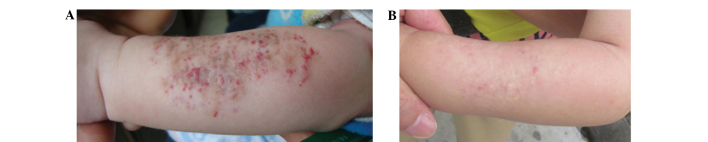

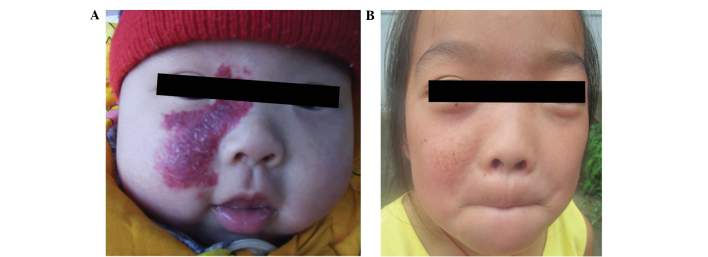

In the observation group, 16 cases were classed as being cured, 1 case showed an excellent response and there were no effective or invalid responses among the 17 subjects aged ≤3 months (Table I); among the 20 subjects aged >3 months, 17 cases were classed as being cured, 3 cases showed an excellent response and there were no effective or invalid responses (Table II). In the control group, 10 cases were classed as being cured, 3 cases showed an excellent response, 2 cases were effective and no cases were invalid among the 15 patients aged ≤3 months (Table I); among the 20 patients aged ≤3 months, 12 cases were classed as being cured, 3 cases were classed as excellent, 5 cases showed an effective response and no cases were invalid (Table II). The cure rates after the different treatment courses are shown in Table III. Examples of excellent and cure responses in variously located superficial hemangioma lesions of the observation group subjects are shown in Fig. 1 and Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Table I.

Comparison of the treatment efficacy in patients aged ≤3 months between the observation and control group.

| Response rate, % (n, total n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Patients, n | Cure | Excellent | Effective | Invalid |

| Observation | 17 | 94.1 (16/17)a | 100 (17/17)b | 100 (17/17)c | 0 (0/17) |

| Control | 15 | 66.7 (10/15) | 86.7 (13/15) | 100 (15/15) | 0 (0/15) |

Observation vs. control group:

χ2=23.22, P<0.01

χ2=13.90, P<0.01

χ2=0, P>0.05.

Table II.

Comparison of the treatment efficacy in patients aged >3 months between the observation and control group.

| Response rate, % (n, total n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Patients, n | Cure | Excellent | Effective | Invalid |

| Observation | 20 | 85.0 (17/20)a | 100 (20/20)b | 100 (20/20)c | 0 (0/20) |

| Control | 20 | 60.0 (12/20) | 75.0 (15/20) | 100 (20/20) | 0 (0/20) |

Observation vs. control group:

χ2=15.67, P<0.01

χ2=28.57, P<0.01

χ2=0, P>0.05.

Table III.

Comparison of the efficacy of the first and second treatment courses between the observation and control groups.

| First course | Second course | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Patients, n | Cure rate, % (n, total n) | Cure time, months | Cure rate, % (n, total n) | Cure time, months |

| Observation | 33 | 33.3 (11/33)a | 3–4 | 100 (33/33)b | 4–9 |

| Control | 22 | 18.2 (4/22) | 3–4 | 100 (22/22) | 4–9 |

Observation vs. control group:

χ2=5.92, P<0.05

χ2=0, P>0.05.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of treatment for a left-eye superficial hemangioma: (A) Before treatment and (B) 1 month after treatment withdrawal. A total dose of 11 Gy 90Sr-90Y was applied in a single course combined with 0.5% topical timolol treatment for 6 months.

Figure 2.

Efficacy of treatment for a left-forearm superficial hemangioma: (A) Before treatment and (B) 6 months after treatment withdrawal. A total dose of 11 Gy 90Sr-90Y was applied in a single course combined with 0.5% topical timolol treatment for 6 months.

Figure 3.

Efficacy of treatment for a left-crus superficial hemangioma: (A) Before treatment and (B) 3 months after treatment withdrawal. A total dose of 22 Gy 90Sr-90Y was applied in 2 courses combined with 0.5% topical timolol treatment for 6 months.

Adverse reactions

Two patients in the observation group exhibited mild pruritus, although in 1 case the patient did not require any additional treatment for the reaction and the symptoms subsided after 3 weeks. The symptoms of the other case were more marked, but subsided following the external application of Elocon ointment (Schering-Plough Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for a few days. Mild normal skin pigmentation 1 cm from the outer edge of the lesion was observed in 6 cases after 1–2 weeks of treatment. Skin color returned to normal after 3 months of treatment with topical vitamin E gel treatment (Sinopharm Xingsha Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China).

In 1 case of a large-area (10.8×6.4 cm) forearm hemangioma, the subject exhibited a fever (38.4°C) after 2 days of 90Sr-90Y application. Analysis revealed that the patient's leukocyte and neutrophil counts were slightly below normal, and the lymphocyte ratio was slightly elevated. The fever subsided following symptomatic treatment for 4 days, and routine blood tests showed normal results after 1 month. Re-examination of the blood 1 month later also showed normal results. In 1 case of orbital superficial hemangioma (Fig. 1), eyelashes that were adjacent to the tumor were temporarily lost after 2 weeks of treatment, but normal eyelash growth was recovered after 6 months of follow-up. Two patients exhibited mild skin flaking subsequent to receiving the topical timolol application, but the symptoms disappeared following the temporary discontinuation of the treatment for 3–5 days. No similar reactions were observed once the dose was reduced.

In the control group, 3 subjects experienced mild itching, which subsided after 2 days of symptomatic treatment. Mild pigmentation of the normal skin adjacent to the tumor edge was observed in 7 cases, which returned to normal between 3 weeks and 2 months later.

In the observation group, the adverse reaction rate was 32.4% (12/37), while the control group adverse reaction rate was 28.6% (10/35), resulting in no significant difference between the groups (χ2=0.212, P>0.05). During the course of treatment, there were no obvious blisters, ulceration, exudation, infection or other wet dermatitis reaction in the two groups. No significant alterations were detected in respiration and heart rate, stool quality, diet or sleep habits and no other systemic adverse reactions were detected. Furthermore, no abnormal changes were observed in liver and kidney function, fasting blood glucose and ECG prior to or following treatment.

Discussion

A variety of methods for treating superficial hemangiomas exist, including lasers, freezing and 90Sr-90Y paste. Laser treatment is convenient and quick, but is associated with an enhanced risk of hemangioma proliferation relapse following treatment. Furthermore, only moderate laser energy should be used, to avoid the formation of local cicatrices. Cryotherapy may cause pain and can lead to hypopigmentation. Among the most effective methods of treating IH are 90Sr-90Y applicators, the use of which has been reported in a number of previous studies (8,9). The total cumulative radiation dose must, however, be strictly controlled, as an excessive dose may result in serious complications. Potential short-term complications of excessive radiation include blisters, infection and ulcers, while possible long-term complications include local pigmentation or hypopigmentation, scar formation, soft tissue dysplasia and bone growth inhibition (10,11). In a previous set of experiments (data not shown), 1 patient with superficial hemangioma received 3 courses of 90Sr-90Y applicator treatment in January 2008, with a total dose of 50 Gy, >2 times the dose of the present study. Mild pigmentation was visible at the treatment site at the 3-year follow-up (Fig. 4). The use of small doses of fractionated irradiation is currently advocated (5), but which may prolong cure time and reduce the pathogenicity of certain IHs with an abundant blood supply.

Figure 4.

Partial pigment formation with high-dose applicator therapy: (A) Before and (B) after treatment. The patient received 3 courses of 90Sr-90Y treatment from January 2008, with a total radiation dose of 50 Gy. Mild pigmentation remained visible on the treatment site at the 3-year follow-up.

The application of propranolol was a crucial development in the treatment of the IH (12). Propranolol is able to effectively control the proliferation of severe hemangioma, and has provided a new drug option for the treatment of hemangioma. The disadvantage of using propranolol is the long cycle of treatment, with countries generally advocating a treatment duration in infant patients of >12 months. Patients that do not complete the prescribed treatment schedule may experience treatment failure or hemangioma relapse. Furthermore, a limited number of infants are not sensitive to propranolol and respond negatively. There may be a variety of adverse responses if propranolol is used to treat small and superficial lesions that are not particularly suitable, including bradycardia, hypotension, hypoglycemia, bronchospasm, drowsiness or insomnia, nightmares, loss of appetite and sweating (13). Recently, Tang et al (7) reported that 90Sr-90Y application combined with propranolol was more effective than single-use 90Sr-90Y applicator therapy for the treatment of infants with large-area skin hemangiomas; however, recipients required close monitoring in order to detect any adverse systemic reactions.

Following research into the clinical application of propranolol, it was found that the topical application of non-selective β-blocker also effectively induced the degradation of skin hemangioma. Timolol is a non-selective β-adrenergic receptor blocker, which was initially used for the treatment of glaucoma in the USA in 1978 (14,15). Timolol treatment has been safely used in clinical pediatrics and has been employed as a first-line treatment for glaucoma in the field of pediatric ophthalmology for 30 years (16). According to previous studies, the pharmacological effects of timolol are 4–10 times more marked than those of propranolol (17–19). Ni et al (19) applied 0.5% timolol eye drops, twice per day, to the faces and necks of 4 patients with IH (age range, 3–10 months). The color of the hemangiomas faded after 2–4 months of treatment, and the affected area was reduced with no obvious adverse reactions. Wang et al (6) treated patients with a 0.5% topical application of timolol three times a day, every 8 h, for 6 consecutive months. The efficacy rate in the treatment group was 64%, which was significantly higher than that in the control group (17.65%) (χ2=43.74, P<0.01) (6). The precise mechanism underlying the timolol-mediated treatment of IH remains unknown; however, we suggest that it involves a similar mechanism to that of oral propranolol therapy (20) and that timolol is able to block the β-receptors of the skin surface in IH or inhibit the expression of VEGF, leading to the inhibition of the tumor growth and the eventual eradication of the hemangioma, concurrent with the induced vasoconstriction.

In the present study, an 90Sr-90Y applicator combined with topical application of timolol was used to treat superficial IH. The total cumulative dose of the 90Sr-90Y applicator radiation and the number of courses (1 or 2) were reduced compared with the norm (21). The rate of responses classed as either a cure or effective was notably increased in the observation group compared with that in the control group. At 3–4 months after the first course of treatment, the cure rate in the observation group (33.3%) was significantly elevated compared with that in the single-use 90Sr-90Y control group (18.2%), which suggested the combined observation group therapy was more effective and rapid. It was frequently noted that, for the guardians of the patients, the desire for an excellent response or cure was secondary to the desire to observe rapid improvements in the superficial appearance of the hemangioma, i.e. an effective response, despite the former two outcomes being more favorable in the long term.

The dose of the therapeutic intervention determines the intensity and persistence of adverse reactions. No serious local or systemic adverse reactions, such as blisters, ulcers, hypoglycemia or bronchial asthma, were observed in the present study. The possible reasons for this may be the elevated local drug concentrations in the hemangioma and the relatively lower systemic plasma drug concentrations, in addition to the reduced 90Sr-90Y treatment doses and total radiation exposure. The local area surrounding the lesion exhibited mild flaking in the observation group, but this subsided following the temporary discontinuation of the treatment for a number of days. This reaction did not reappear once the dose of timolol was reduced appropriately, which may be associated with the individual sensitivity to the timolol. In 6 cases in the observation group, mild pigmentation of the normal skin was observable 1 cm from the outer edge of the lesions after 1–2 weeks of treatment. Skin color returned to normal following the topical application of vitamin E gel for 3 months, which may have been due to the vitamin E exerting antioxidative, free radical-scavenging and whitening effects that promoted pigment-fading. In 1 case of orbital vascular tumor, the patient's eyelashes fell off after 1 course of treatment (11 Gy), but regrew after 6 months. According to previous treatment experience, the use of a low-dose radiation applicator for the treatment of hemangiomas in areas with hair covering (orbital cavity, head) may result in temporary alopecia; however, the majority of patients will recover hair growth at a later stage. A variety of topical systemic adverse reactions have been reported as a result of timolol application, including bronchial spasm, cough, respiratory failure, nightmares and confusion (22). Close observation is therefore advisable to prevent the occurrence of adverse reactions during treatment, particularly in infants that are premature or exhibit cardiopulmonary dysfunction.

In summary, the results of the present study indicate that a combined treatment using an 90Sr-90Y applicator and local external application of 0.5% timolol eye drops exhibits a number of advantages for the treatment of IH, including rapid onset, efficacy, convenient administration, low cost and reduced adverse reactions, particularly for the treatment of superficial lesions on the face and eye area. The combined treatment described therefore possesses the potential for clinical application. However, due to the limited sample size and follow-up period (maximum 1 year) of the present study, the long-term complications of the therapy remain unknown. In addition, future studies are required to determine whether the therapeutic effects observed in the present study may be achieved using a further-reduced total dose of 90Sr-90Y.

References

- 1.Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M, Hamm H, Sebastian G. Hemangiomas of infancy and childhood. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5:334–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06168.x-i1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uihlein LC, Liang MG, Mulliken JB. Pathogenesis of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatric Annals. 2012;41:1–6. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20120727-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chakkittakandiyil A, Phillips R, Frieden IJ, Siegfried E, Lara-Corrales I, Lam J, Bergmann J, Bekhor P, Poorsattar S, Pope E. Timolol maleate 0.5% or 0.1% gel-forming solution for infantile hemangiomas: A retrospective, multicenter, cohort study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:28–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope E, Chakkittakandiyil A. Topical timolol gel for infantile hemangiomas: A pilot study. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:564–565. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou IQ. The Operation Standard in Clinical Technology Nuclear Medicine Fascicule. Chinese Medical Association. People's Military Medical Press; Beijing: 2004. Radiation treatment of nuclear application; pp. 194–196. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YM, Geng F, Zha ZY, Cheng R, Zhang ZY, Su WJ, Zhang YX. Effectiveness of 0.5% solution of topical maleate for infantile Hemangiomas. Zu Zhi Gon Cheng Yu Zhong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi She. 2012;8:208–212. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang ZW, Huang JH, Tang JH. Clinical efficacy of 90Sr-90Y applicator combined with propranolol treatment on large infantile cutaneous hemangiomas. Zhong Hua He Yi Xue Xa Zhi. 2013;33:49–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin TS, Chen WM. Clinical analysis of 90Sr-90Y applicator treatment for 2862 infantile cutaneous capillary hemangiomas. Fu Jian Yi Yao Za Zhi She. 2010;32:21–22. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xi Z, Chen F, Lu L. Effectiveness analysis of 90Sr/90Y applicator treatment for 107 infantile capillary hemangiomas. Biao Ji Mian Yi Fen Xi Yu Lin Chuang Bian Ji Bu. 2012;19:247–248. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang JD, Wang YC, Lv C, et al. Analysis of nuclide radiation treatment for 1076 infantile hemangiomas. Ren Min Jun Yi. 2011;54:224–225. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fragu P, Lemarchand-Venencie F, Benhamou S, François P, Jeannel D, Benhamou E, Sezary-Lartigau I, Avril MF. Long-term effect in skin and thyroid after radiotherapy for skin angiomas: A French retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 1991;27:1215–1222. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(91)90084-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan ST, Itinteang T, Leadbitter P. Low-dose propranolol for infantile haemangioma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64:292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiestl C, Neuhaus K, Zoller S, Subotic U, Forster-Kuebler I, Michels R, Balmer C, Weibel L. Efficacy and safety of propranolol as fist-line treatment for infantile hemangiomas. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:493–501. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Buskirk EM, Fraunfelder FT. Timolol and glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99:696. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010696022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciudad Blanco C, Campos Domínguez M, Moreno García B, Villanueva Álvarez-Santullano CA, Berenguer Fröhner B, Suárez Fernández R. Episcleral infantile hemangioma successfully treated with topical timolol. Dermatol Ther. 2015;28:22–24. doi: 10.1111/dth.12173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coppens G, Stalmans I, Zeyen T, Casteels I. The safety and efficacy of glaucoma medication in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46:12–18. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20090101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lohmöller G, Frohilch ED. A comparison of timolol and propranolol in essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 1975;89:437–442. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90148-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Achong MR, Piafsky KM, Ogilvie RI. Duration of cardiac effects of timolol and propranolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976;19:148–152. doi: 10.1002/cpt1976192148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ni N, Langer P, Wagner R, Guo S. Topical timolol for periocular hemangioma: Report of further study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:377–379. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L, Mai HM, Zheng JW. The mechanisms of propranolol treatment for infantile hemangiomas and advances in research. Zhong Guo Kou Qiang Zuo Mian Wai Ke Za Zhi She. 2012;10:342–346. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ding SM, Qu W, Wang SJ, Feng J, Zheng XH, Song C. Clinical observation of hemangioma treated by 90Sr/90Y application. Zhong Guo Pi Fu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi She. 2006;11:673–674. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon P, Oza V, Frieden IJ. Topical timolol for infantile hemangiomas: Putting a note of caution in ‘cautiously optimistic’. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:127–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]