Abstract

New radiation modalities have made it possible to prolong the survival of individuals with malignant brain tumors, but symptomatic radiation necrosis becomes a serious problem that can negatively affect a patient’s quality of life through severe and lifelong effects. Here we review the relevant literature and introduce our original concept of the pathophysiology of brain radiation necrosis following the treatment of brain, head, and neck tumors. Regarding the pathophysiology of radiation necrosis, we introduce two major hypotheses: glial cell damage or vascular damage. For the differential diagnosis of radiation necrosis and tumor recurrence, we focus on the role of positron emission tomography. Finally, in accord with our hypothesis regarding the pathophysiology, we describe the promising effects of the anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody bevacizumab on symptomatic radiation necrosis in the brain.

Keywords: bevacizumab, positron emission tomography, pseudoprogression, radiation necrosis

Introduction

Most patients who develop radiation necrosis in the brain originally received radiation treatment for either brain tumors or head and neck cancers. In rare cases, radiation treatment for vascular lesions such as arteriovenous malformations may cause radiation necrosis, but the treatment modality and doses are quite different between the treatments for tumors and vascular lesions. In this review, therefore, we focus on radiation necrosis in the brain that is derived from radiation treatment for brain tumors and, head and neck cancers.

Radiation necrosis in the brain is often encountered after the treatment of metastatic brain tumors, especially by stereotactic radiosurgery, the incidence rate following stereotactic radiosurgery for such tumors is up to 68%.1–4) Numerous reports have also linked radiation necrosis to the treatment of primary brain tumors. The incidence of radiation necrosis in the setting of focal radiotherapy has been estimated as 3–24%.5–11) The most important factors in the risk of cerebral radiation necrosis are the radiation dose, the fraction size, and the subsequent administration of chemotherapy.8) A smaller fraction size even with the same total radiation dose will increase the biological effective dose and subsequently the incidence of radiation necrosis. For concurrent chemotherapy for malignant gliomas, the incidence increases by threefold.12–14) At least in patients who receive radiosurgery, the irradiated volume is also critical in terms of the risk of radiation necrosis7,15–17) and re-irradiation or additional boost radiation treatment by stereotactic radiotherapy pose additional risk as well.8)

There are two distinct concepts of radiation-induced injury in the brain. One is pseudoprogression and the other is radiation necrosis. Generally speaking, pseudoprogression occurs relatively earlier (i.e., 2–5 months after the initiation of adjuvant treatment), and is generally detected by contrast enhancement in neuro-imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Pseudoprogression usually shows a self-limited course and eventual resolution, both clinically and radiographically.12–14,18) Radiation necrosis occurs rather later than pseudoprogression, after the treatment, and often does not subside without intensive treatment. Histologically, radiation necrosis is found mainly in white matter with endothelial damage, perilesional edema, and gliosis, as described below.19–24) Sometimes pseudoprogression also shows symptoms,25) and occasionally it is difficult to differentiate pseudoprogression and radiation necrosis. In addition, pseudoprogression, radiation necrosis, and tumor recurrence are difficult to differentially diagnose, especially with neuroimaging modalities such as MRI.

Clearly, the risk of radiation-induced injury that attends radiation treatment is a significant challenge.

Pathophysiology of Radiation Necrosis

The histopathological characteristics of radiation necrosis include coagulation and liquefaction necrosis in the white matter, with capillary collapse and wall thickening and hyalinization of the vessels.26–30) Telangiectasia is also reported to be a result of the genesis of collateral blood flow against ischemia caused by the obstruction of small venules and arterioles, as reported in a monograph by Burger and Boyko.31) These histological changes seem to be caused by chronic inflammation and microcirculatory impairment.19,21–23,32–34)

With respect to the cause of radiation necrosis, two hypotheses have been put forward. One postulates that the necrosis arises due to direct injury of the brain parenchyma, especially glial cells. According to this hypothesis, radiation treatment directly injures the brain parenchyma, leading to secondary damage to vessels. The primary damage is focused on glial cells, especially oligodendrocytes, creating demyelination in the white matter.35,36) However, this hypothesis is not supported widely because even low doses of radiation that cannot result in histological necrosis cause a decrease in the number of glial cells.30,37) The other hypothesis is that the direct primary injury to the blood vessels causes the brain parenchymal injury as secondary damage.38) This hypothesis has been widely accepted because vascular injury was observed prior to the development of radiation necrosis in a rodent radiation necrosis model.39–41)

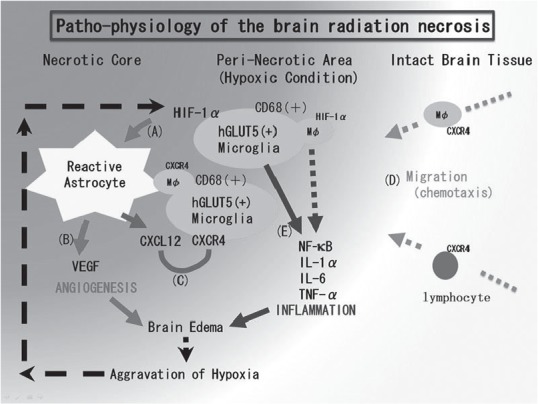

We recently published our original hypothesis based on histopathological findings from human radiation necrosis surgical specimens (Fig. 1).42) We considered that the first step in the development of radiation necrosis in a brain that has undergone radiation treatment is blood vessel damage just around the tumor. This is associated with hypoxia close to the irradiated tumor tissue, which causes the upregulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) in human glucose transporter 5 (hGLUT5)- and CD68-positive microglia. We based this hypothesis on our finding that HIF-1α is upregulated in the perinecrotic area in radiation necrosis specimens (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

The pathophysiology of brain radiation necrosis: our hypothesis. A: Vascular damage around the irradiated tumor tissue causes tissue ischemia. This hypoxia induces hGLUT5-positive microglia to express hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) around the necrotic core. B: Under HIF-1α regulation, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is expressed in reactive astrocytes, causing leaky and fragile angiogenesis. C: CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling is also regulated by HIF-1α. D: CXCL12-expressing reactive astrocytes might draw CXCR4-expressing macrophages and lymphocytes by chemotaxis into the perinecrotic area. E: These accumulated hGLUT5-positive microglia producing NF-κB and pro-inflammatory cytokines seem to aggravate radiation necrosis. This figure was taken from our recent publication (Reference 42) with the permission of the publisher. CXCL12: C-X-C motif chemokine 12, CXCR4: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, hGLUT5: human glucose transporter 5, IL: interleukin, NF-κB: nuclear factor-kappa B, TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

Fig. 2.

Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) immunohistochemistry of radiation necrosis. A, B: The results of HIF-1α immunohistochemistry on the radiation necrosis in a patient with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) who was treated by re-irradiation with boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT). The (A) intact brain area and (B) peri-necrotic area are shown. C, D: HIF-1α immunohistochemistry in patients with radiation necrosis from GBM and metastatic brain tumors, respectively. The former was treated with proton beam radiation and X-ray treatment as an initial treatment, while the latter was treated with repetitive BNCT at the recurrence. Int: intact brain, Ne: necrotic center, Pe: peri-necrotic area. The original objective magnification is ×40.

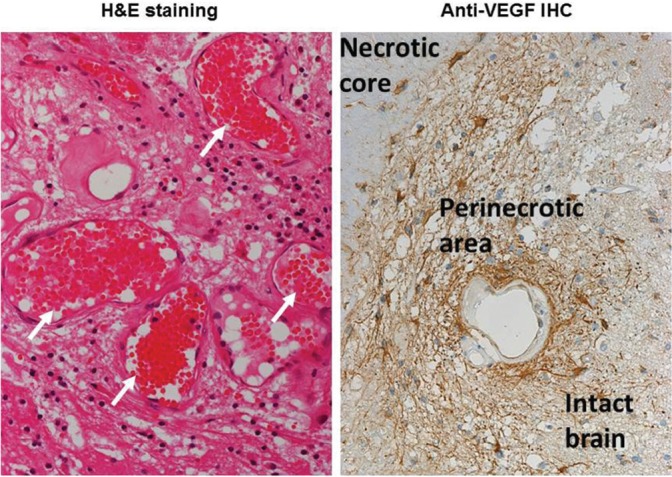

Because HIF-1α is well known as a transactivator of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling,43,44) the upregulation of HIF-1α augments VEGF and CXCL12 expression in glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive reactive astrocytes. The VEGF expression produces the leaky and fragile angiogenesis and the subsequent perilesional edema in radiation necrosis (Fig. 3).45) The C-X-C motif chemokine 12 (CXCL12) expression might draw C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4)-expressing hGLUT5-positive microglia and CXCR4-expressing lymphocytes by chemotaxis to the perinecrotic area. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α] by these accumulated hGLUT5-positive cells seem to aggravate the perilesional edema.

Fig. 3.

Surgical specimen of radiation necrosis derived from a metastatic brain tumor caused by stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). Hematoxylin and Eosin staining shows marked angiogenesis (indicated by white arrows) with perilesional edema. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) immunohistochemistry shows the abundant expression of VEGF in the perinecrotic area. The VEGF-producing cells seemed to be reactive astrocytes.

However, we found that although some CD45-positive lymphocytes gathered in the perinecrotic area, they were not involved in pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a key player in inflammation, would be expected to play a significant role in radiation necrosis. The aggravation of edema could lead to the further development of focal ischemia, which augments the expression of HIF-1α in the microglia in the perinecrotic area. Here, both angiogenesis and inflammation may contribute to a synergistic and malignant cycle in radiation necrosis. In any case, our observations suggest that inflammation participates in the pathophysiology of brain radiation necrosis, as Yoshi suggested.34)

Among the proinflammatory cytokines, one key upstream player is TNF-α, which regulates other cytokines to increase the blood-brain barrier’s permeability, increase leukocyte adhesion, activate astrocytes, and induce endothelial apoptosis.32,46,47) An important downstream molecule is intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), which is expressed on the surface of endothelial cells and is a principal mediator of leucocyte-endothelial cell adhesion.47–52) Our recent study provided evidence that platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) and their receptor families also play a significant role in cerebral radiation necrosis from the viewpoints of angiogenesis and inflammation.53) However, to save the space of this article, we will omit the details of the participation of PDGFs and their receptor families in radiation necrosis.

Diagnosis of Radiation Necrosis

There is no question that surgical exploration including biopsy is the gold standard for the histological confirmation of radiation necrosis or tumor progression. Irradiation is generally applied to surgically inaccessible lesions. In addition, biopsies occasionally show a mixture of radiation necrosis in most parts of the specimen but some viable tumor cells in other parts. It is important for clinicians to determine the next best treatment based on the correct diagnosis of radiation necrosis or tumor progression. When we encounter increasing edema and a contrast-enhanced lesion after the radiation treatment of a brain tumor or head or neck cancer, this next best treatment must be identified. If we judge the cause of increasing edema as radiation necrosis, we can choose from among several treatment options including bevacizumab, as described below. In contrast, if we judge the cause of edema as tumor progression, re-irradiation may be preferable.54)

I. MRI, ADC, MRS, and MR perfusion imaging

A typical characteristic of radiation necrosis in Gd-enhanced T1-weighted MRI is called “Swiss cheese” or “soap bubble” enhancement.6) However, conventional MRI is not sufficient to differentiate tumor progression/recurrence from treatment-related effects.5,6,11,55)

The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) may be important to differentiate tumor recurrence and radiation necrosis. In tumor recurrence, the ADC is low, because high cellularity restricts water mobility. An increased ADC is ascribed to increased water mobility in radiation necrosis.56–58) Several research groups have attempted to differentiate radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) from the viewpoint of metabolism.11,59–61) In radiation necrosis, N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) and creatinine (Cr) generally decrease, whereas high choline (Cho) is correlated with tumor progression.61–67) The Cho/Cr ratio and the Cho/NAA ratio have been described as good landmarks for differential diagnosis.59,60,68) MR perfusion techniques using contrast enhancement can measure the relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and estimate the vascularity and hemodynamics. Hyperperfusion is seen in tumor progression, and hypoperfusion is seen in radiation necrosis.69–71) Sugahara et al. reported that rCBV values < 0.6 suggest radiation necrosis and values > 2.6 suggest tumor progression.72)

II. Positron emission tomography (PET)

PET scan can directly demonstrate the metabolism of the brain or lesions such as radiation necrosis or tumor progression. Several studies using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) as a tracer initially suggested good sensitivity and specificity,73–78) but there is a paucity of histological correlations in these reports. Other studies using the same tracer showed unpromising results with decreased sensitivity and specificity.79–83)

The main reasons for this uncertainty about the utility of this tracer for the differentiation of radiation necrosis and tumor progression are as follows. The brain shows high sugar metabolism, and FDG-PET reveals a very high metabolic background in the normal brain. Moreover, FDG accumulates well in cases of inflammation.84) However, inflammatory cells commonly infiltrate at the radiation necrosis border as well as in normal brain tissue.26,85) It thus remains rather difficult to apply FDG-PET to discriminate between radiation necrosis and tumor progression.86) Indeed, it has been reported that some radiation necrosis cases show good accumulation of FDG despite the absence of evidence of tumor recurrence.87)

PET imaging using amino acids as tracers is promising for the detection of malignant tumors in the brain, because the background activity of protein metabolism in the brain is rather low compared to its sugar metabolism. 11C-labeled methionine (C-MET) has been used as a tracer for amino-PET, and for analyzing the metabolism in malignant brain tumors88,89) as well as for differentiating between radiation necrosis and tumor progression.89) In addition, 18F-labeled fluoroboronophenylalanine (F-BPA)-PET is very useful for the discrimination of radiation necrosis and tumor progression, as we have described in earlier studies.90,91) We are currently conducting a nationwide multicenter clinical trial under the rubric of “Intravenous administration of bevacizumab for the treatment of radiation necrosis in the brain with diagnosis based on amino acid PET” as Type 3 Investigational Medical Care System and Advanced Therapy, and has been approved by Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW).92)

Treatments for Radiation Necrosis

I. Surgical treatments

The surgical excision of radiation necrosis had been a gold-standard treatment for symptomatic radiation necrosis, in order to rapidly reduce the increased intracranial pressure.93) However, as described above, radiation treatment is often applied to surgically inaccessible lesions, and sometimes this surgical intervention worsens the patient’s neurological condition, as we described previously.45) Nonetheless, the indications for the removal of radiation necrosis should be decided carefully and strictly, and potent medical treatment should be developed for use in its stead.

II. Medical treatments other than bevacizumab

Corticosteroids have been used to treat radiation necrosis in the brain for several decades.94,95) The rationale underlying this steroid usage is that the radiation-induced vascular endothelial damage and resulting breakdown of the blood-brain barrier must be reversed. Some inflammatory responses may also be lessened by corticosteroids. The long-term use of corticosteroids can be expected to cause numerous adverse effects such as hypertension, hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, weight changes, moon face, psychiatric disturbances, and immunosuppression, all of which can severely decrease an individual’s quality of life.

As an initial step in the development of radiation necrosis, a hypoxic condition is caused by the damage to the microcirculation near a tumor treated with radiation treatment, as shown in Fig. 1. To improve such microcirculation impairments, anticoagulants and antiplatelets have been used to some effect, but not with satisfactory results.96) Hyperbaric oxygen treatment has also been used to treat radiation necrosis in the brain to stimulate angiogenesis and the repair of the regional cerebral blood supply compromised by radiation-mediated circulatory injury.97–99) However, there has been no large-scale study with distinct conclusions. At least one study has reported the use of hyperbaric oxygenation for the prophylaxis of radiation injury in the treatment of metastatic brain tumors with stereotactic radiosurgery.100)

III. Medical treatments with bevacizumab

As shown in our surgical specimen and reflected in our hypothesis (Figs. 1, 2), HIF-1α upregulation in the perinecrotic area is an initial step in the development of radiation necrosis in the brain. VEGF overproduction in reactive astrocytes then occurs; this is the most clear-cut cause of leaky and fragile angiogenesis and subsequent cerebral edema in radiation necrosis in the brain, as described above.42,45) A reasonable strategy to reduce this overexpression of VEGF is the use of the anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, bevacizumab.

The first report to describe the efficacy of bevacizumab for radiation necrosis was published by Gonzalez et al. in 2007.101) In that report, bevacizumab was used as an additional chemotherapeutic agent for recurrent malignant gliomas and the authors noted retrospectively that the cases in which bevacizumab was effective seemed to be those that involved radiation necrosis. Several later studies found that bevacizumab is effective as a treatment for radiation necrosis in the brain irrespective of the original histological tumor type (including metastatic brain tumors) and the applied radiation modalities.102–106) A placebo-controlled randomized trial of bevacizumab was published with class 1 evidence, although the number of patients was limited.107)

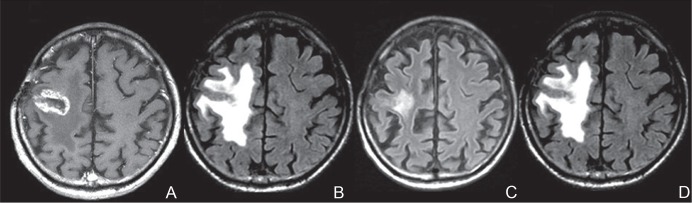

We have also routinely observed the effectiveness of bevacizumab for radiation necrosis, as shown in Fig. 4. However, we also sometimes encounter the aggravation of radiation necrosis after a transient improvement in neuro-imaging and clinical neurological findings (Fig. 4). Almost all of the relevant studies have observed promising effects of bevacizumab, but one review article raised the possibility of adverse effects such as cerebral hemorrhage and thrombo-embolitic complications.108)

Fig. 4.

A representative case of radiation necrosis treated with bevacizumab. The original disease was a metastatic brain tumor from lung cancer. The metastasis was treated with SRS. One year after the SRS, marked enhancement (A) and perilesional edema (B) were recognized on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). At the time of the MRI, the patient could not walk by himself. After three cycles of bevacizumab treatment 5 mg/kg biweekly, an MRI showed a marked decrease of the edema (C) and he could walk again. Unfortunately, 3 months after the bevacizumab treatment, MRI showed aggravation of the edema (D) with clinical symptom deterioration. Due to financial problems, the patient could not undergo a re-challenge of bevacizumab treatment. A: Gd-enhanced T1-weighted image. B–D: Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery images. SRS: stereotactic radiosurgery.

In many cases, however, cerebral radiation necrosis itself has shown a trend of spontaneous hemorrhage around the lesion as a natural course.45) Moreover, bevacizumab may be used for the prophylaxis of possible radiation necrosis in re-irradiation109,110) and may improve the clinical results such as the overall survival after re-irradiation itself.111) In addition to angiogenesis, we hypothesized that there is a significant role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of radiation necrosis, as shown in Fig. 1. In support of this hypothesis, preliminary reports have indicated that anti-TNF antibody may be effective for the treatment of cerebral radiation necrosis.32,46,47)

Conclusion

Clinicians must bear in mind that radiation treatment carries a risk of radiation-induced injury. Whenever encountering an aggravation of cerebral edema after irradiation for brain tumors or head and neck cancers, it is important to remember that not only tumor progression but also radiation necrosis is possible. At that time, a correct diagnosis and prompt treatment decisions are mandatory to avoid exacerbation of the patient’s condition. Re-irradiation should never be applied for possible radiation necrosis. If the lesion can be diagnosed as radiation necrosis, bevacizumab should be considered as a first-line treatment. We are currently trying to obtain the approval for the on-label use of bevacizumab for the treatment of radiation necrosis in Japan from the MHLW.

References

- 1). Blonigen BJ, Steinmetz RD, Levin L, Lamba MA, Warnick RE, Breneman JC: Irradiated volume as a predictor of brain radionecrosis after linear accelerator stereotactic radiosurgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 77: 996– 1001, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Minniti G, Clarke E, Lanzetta G, Osti MF, Trasimeni G, Bozzao A, Romano A, Enrici RM: Stereotactic radiosurgery for brain metastases: analysis of outcome and risk of brain radionecrosis. Radiat Oncol 6: 48, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Minniti G, D'Angelillo RM, Scaringi C, Trodella LE, Clarke E, Matteucci P, Osti MF, Ramella S, Enrici RM, Trodella L: Fractionated stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases. J Neurooncol 117: 295– 301, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Telera S, Fabi A, Pace A, Vidiri A, Anelli V, Carapella CM, Marucci L, Crispo F, Sperduti I, Pompili A: Radionecrosis induced by stereotactic radiosurgery of brain metastases: results of surgery and outcome of disease. J Neurooncol 113: 313– 325, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Brandsma D, Stalpers L, Taal W, Sminia P, van den Bent MJ: Clinical features, mechanisms, and management of pseudoprogression in malignant gliomas. Lancet Oncol 9: 453– 461, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Kumar AJ, Leeds NE, Fuller GN, Van Tassel P, Maor MH, Sawaya RE, Levin VA: Malignant gliomas: MR imaging spectrum of radiation therapy- and chemotherapy-induced necrosis of the brain after treatment. Radiology 217: 377– 384, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Marks JE, Baglan RJ, Prassad SC, Blank WF: Cerebral radionecrosis: incidence and risk in relation to dose, time, fractionation and volume. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 7: 243– 252, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Ruben JD, Dally M, Bailey M, Smith R, McLean CA, Fedele P: Cerebral radiation necrosis: incidence, outcomes, and risk factors with emphasis on radiation parameters and chemotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 65: 499– 508, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Shaw E, Arusell R, Scheithauer B, O'Fallon J, O'Neill B, Dinapoli R, Nelson D, Earle J, Jones C, Cascino T, Nichols D, Ivnik R, Hellman R, Curran W, Abrams R: Prospective randomized trial of low- versus high-dose radiation therapy in adults with supratentorial low-grade glioma: initial report of a North Central Cancer Treatment Group/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 20: 2267– 2276, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Soffietti R, Sciolla R, Giordana MT, Vasario E, Schiffer D: Delayed adverse effects after irradiation of gliomas: clinicopathological analysis. J Neurooncol 3: 187– 192, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Zeng QS, Li CF, Zhang K, Liu H, Kang XS, Zhen JH: Multivoxel 3D proton MR spectroscopy in the distinction of recurrent glioma from radiation injury. J Neurooncol 84: 63– 69, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12). Brandes AA, Franceschi E, Tosoni A, Blatt V, Pession A, Tallini G, Bertorelle R, Bartolini S, Calbucci F, Andreoli A, Frezza G, Leonardi M, Spagnolli F, Ermani M: MGMT promoter methylation status can predict the incidence and outcome of pseudo-progression after concomitant radiochemotherapy in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. J Clin Oncol 26: 2192– 2197, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Chamberlain MC, Glantz MJ, Chalmers L, Van Horn A, Sloan AE: Early necrosis following concurrent Temodar and radiotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. J Neurooncol 82: 81– 83, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14). de Wit MC, de Bruin HG, Eijkenboom W, Sillevis Smitt PA, van den Bent MJ: Immediate post-radiotherapy changes in malignant glioma can mimic tumor progression. Neurology 63: 535– 537, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Lee AW, Kwong DL, Leung SF, Tung SY, Sze WM, Sham JS, Teo PM, Leung TW, Wu PM, Chappell R, Peters LJ, Fowler JF: Factors affecting risk of symptomatic temporal lobe necrosis: significance of fractional dose and treatment time. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 53: 75– 85, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16). Shaw E, Scott C, Souhami L, Dinapoli R, Kline R, Loeffler J, Farnan N: Single dose radiosurgical treatment of recurrent previously irradiated primary brain tumors and brain metastases: final report of RTOG protocol 90-05. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 47: 291– 298, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Sheline GE, Wara WM, Smith V: Therapeutic irradiation and brain injury. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 6: 1215– 1228, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Graeb DA, Steinbok P, Robertson WD: Transient early computed tomographic changes mimicking tumor progression after brain tumor irradiation. Radiology 144: 813– 817, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Belka C, Budach W, Kortmann RD, Bamberg M: Radiation induced CNS toxicity—molecular and cellular mechanisms. Br J Cancer 85: 1233– 1239, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Li YQ, Ballinger JR, Nordal RA, Su ZF, Wong CS: Hypoxia in radiation-induced blood-spinal cord barrier breakdown. Cancer Res 61: 3348– 3354, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, Palmer TD: Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med 8: 955– 962, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD: Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 302: 1760– 1765, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Tofilon PJ, Fike JR: The radioresponse of the central nervous system: a dynamic process. Radiat Res 153: 357– 370, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). Zhao W, Robbins ME: Inflammation and chronic oxidative stress in radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: therapeutic implications. Curr Med Chem 16: 130– 143, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25). Miyatake S, Furuse M, Kawabata S, Maruyama T, Kumabe T, Kuroiwa T, Ono K: Bevacizumab treatment of symptomatic pseudoprogression after boron neutron capture therapy for recurrent malignant gliomas. Report of 2 cases. Neuro-oncology 15: 650– 655, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Burger PC, Mahley MS, Dudka L, Vogel FS: The morphologic effects of radiation administered therapeutically for intracranial gliomas: a postmortem study of 25 cases. Cancer 44: 1256– 1272, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Gaensler EH, Dillon WP, Edwards MS, Larson DA, Rosenau W, Wilson CB: Radiation-induced telangiectasia in the brain simulates cryptic vascular malformations at MR imaging. Radiology 193: 629– 636, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Poussaint TY, Siffert J, Barnes PD, Pomeroy SL, Goumnerova LC, Anthony DC, Sallan SE, Tarbell NJ: Hemorrhagic vasculopathy after treatment of central nervous system neoplasia in childhood: diagnosis and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 16: 693– 699, 1995. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Rabin BM, Meyer JR, Berlin JW, Marymount MH, Palka PS, Russell EJ: Radiation-induced changes in the central nervous system and head and neck. Radiographics 16: 1055– 1072, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). van der Kogel AJ: Radiation-induced damage in the central nervous system: an interpretation of target cell responses. Br J Cancer Suppl 7: 207– 217, 1986. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Burger P, Boyko O: The pathology of central nervous system radiation injury , in Gutin PH, Leibel SA, Sheline GE. (eds): Radiation Injury to the Nervous System . New York : Raven Press , 1991 , pp 191 – 208 [Google Scholar]

- 32). Ansari R, Gaber MW, Wang B, Pattillo CB, Miyamoto C, Kiani MF: Anti-TNFA (TNF-alpha) treatment abrogates radiation-induced changes in vacular density and tissue oxygenation. Radiat Res 167: 80– 86, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). Kishi K, Petersen S, Petersen C, Hunter N, Mason K, Masferrer JL, Tofilon PJ, Milas L: Preferential enhancement of tumor radioresponse by a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Cancer Res 60: 1326– 1331, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Yoshii Y: Pathological review of late cerebral radionecrosis. Brain Tumor Pathol 25: 51– 58, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). van der Maazen RW, Kleiboer BJ, Verhagen I, van der Kogel AJ: Irradiation in vitro discriminates between different O-2A progenitor cell subpopulations in the perinatal central nervous system of rats. Radiat Res 128: 64– 72, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). van der Maazen RW, Kleiboer BJ, Verhagen I, van der Kogel AJ: Repair capacity of adult rat glial progenitor cells determined by an in vitro clonogenic assay after in vitro or in vivo fractionated irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol 63: 661– 666, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Fike JR, Cann CE, Turowski K, Higgins RJ, Chan AS, Phillips TL, Davis RL: Radiation dose response of normal brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 14: 63– 70, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Allen NJ, Barres BA: Neuroscience: Glia—more than just brain glue. Nature 457: 675– 677, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Calvo W, Hopewell JW, Reinhold HS, Yeung TK: Time- and dose-related changes in the white matter of the rat brain after single doses of X rays. Br J Radiol 61: 1043– 1052, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40). Lyubimova N, Hopewell JW: Experimental evidence to support the hypothesis that damage to vascular endothelium plays the primary role in the development of late radiation-induced CNS injury. Br J Radiol 77: 488– 492, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Reinhold HS, Calvo W, Hopewell JW, van der Berg AP: Development of blood vessel-related radiation damage in the fimbria of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 18: 37– 42, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Yoritsune E, Furuse M, Kuwabara H, Miyata T, Nonoguchi N, Kawabata S, Hayasaki H, Kuroiwa T, Ono K, Shibayama Y, Miyatake S: Inflammation as well as angiogenesis may participate in the pathophysiology of brain radiation necrosis. J Radiat Res 55: 803– 811, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Liang Z, Brooks J, Willard M, Liang K, Yoon Y, Kang S, Shim H: CXCR4/CXCL12 axis promotes VEGF-mediated tumor angiogenesis through Akt signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 359: 716– 722, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, Clifford SC, Vaux EC, Cockman ME, Wykoff CC, Pugh CW, Maher ER, Ratcliffe PJ: The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399: 271– 275, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45). Nonoguchi N, Miyatake S, Fukumoto M, Furuse M, Hiramatsu R, Kawabata S, Kuroiwa T, Tsuji M, Fukumoto M, Ono K: The distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor-producing cells in clinical radiation necrosis of the brain: pathological consideration of their potential roles. J Neurooncol 105: 423– 431, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46). Mayhan WG: Cellular mechanisms by which tumor necrosis factor-alpha produces disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res 927: 144– 152, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47). Wilson CM, Gaber MW, Sabek OM, Zawaski JA, Merchant TE: Radiation-induced astrogliosis and blood-brain barrier damage can be abrogated using anti-TNF treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 74: 934– 941, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48). Dobbie MS, Hurst RD, Klein NJ, Surtees RA: Upregulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression on human endothelial cells by tumour necrosis factor-alpha in an in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier. Brain Res 830: 330– 336, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49). Gaber MW, Sabek OM, Fukatsu K, Wilcox HG, Kiani MF, Merchant TE: Differences in ICAM-1 and TNF-alpha expression between large single fraction and fractionated irradiation in mouse brain. Int J Radiat Biol 79: 359– 366, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50). Meistrell ME, Botchkina GI, Wang H, Di Santo E, Cockroft KM, Bloom O, Vishnubhakat JM, Ghezzi P, Tracey KJ: Tumor necrosis factor is a brain damaging cytokine in cerebral ischemia. Shock 8: 341– 348, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51). Nordal RA, Wong CS: Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and blood-spinal cord barrier disruption in central nervous system radiation injury. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 63: 474– 483, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52). Sumagin R, Sarelius IH: TNF-alpha activation of arterioles and venules alters distribution and levels of ICAM-1 and affects leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2116– H2125, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53). Miyata T, Toho T, Nonoguchi N, Furuse M, Kuwabara H, Yoritsune E, Kawabata S, Kuroiwa T, Miyatake S: The roles of platelet-derived growth factors and their receptors in brain radiation necrosis. Radiat Oncol 9: 51, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54). Miyatake S: [Diagnosis and treatment of symptomatic radiation necrosis in the brain]. No Shinkei Geka 41: 197– 208, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55). Mullins ME, Barest GD, Schaefer PW, Hochberg FH, Gonzalez RG, Lev MH: Radiation necrosis versus glioma recurrence: conventional MR imaging clues to diagnosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26: 1967– 1972, 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56). Asao C, Korogi Y, Kitajima M, Hirai T, Baba Y, Makino K, Kochi M, Morishita S, Yamashita Y: Diffusion-weighted imaging of radiation-induced brain injury for differentiation from tumor recurrence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 26: 1455– 1460, 2005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57). Biousse V, Newman NJ, Hunter SB, Hudgins PA: Diffusion weighted imaging in radiation necrosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 74: 382– 384, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58). Hein PA, Eskey CJ, Dunn JF, Hug EB: Diffusion-weighted imaging in the follow-up of treated high-grade gliomas: tumor recurrence versus radiation injury. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 25: 201– 209, 2004. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59). Dowling C, Bollen AW, Noworolski SM, McDermott MW, Barbaro NM, Day MR, Henry RG, Chang SM, Dillon WP, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB: Preoperative proton MR spectroscopic imaging of brain tumors: correlation with histopathologic analysis of resection specimens. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 22: 604– 612, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60). Plotkin M, Eisenacher J, Bruhn H, Wurm R, Michel R, Stockhammer F, Feussner A, Dudeck O, Wust P, Felix R, Amthauer H: 123I-IMT SPECT and 1H MR-spectroscopy at 3.0 T in the differential diagnosis of recurrent or residual gliomas: a comparative study. J Neurooncol 70: 49– 58, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61). Rock JP, Scarpace L, Hearshen D, Gutierrez J, Fisher JL, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T: Associations among magnetic resonance spectroscopy, apparent diffusion coefficients, and image-guided histopathology with special attention to radiation necrosis. Neurosurgery 54: 1111– 1117; discussion 1117–1119, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62). Chong VF, Rumpel H, Aw YS, Ho GL, Fan YF, Chua EJ: Temporal lobe necrosis following radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: 1H MR spectroscopic findings. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 45: 699– 705, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63). Rabinov JD, Lee PL, Barker FG, Louis DN, Harsh GR, Cosgrove GR, Chiocca EA, Thornton AF, Loeffler JS, Henson JW, Gonzalez RG: In vivo 3-T MR spectroscopy in the distinction of recurrent glioma versus radiation effects: initial experience. Radiology 225: 871– 879, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64). Schlemmer HP, Bachert P, Henze M, Buslei R, Herfarth KK, Debus J, van Kaick G: Differentiation of radiation necrosis from tumor progression using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuroradiology 44: 216– 222, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65). Schlemmer HP, Bachert P, Herfarth KK, Zuna I, Debus J, van Kaick G: Proton MR spectroscopic evaluation of suspicious brain lesions after stereo-tactic radiotherapy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 22: 1316– 1324, 2001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66). Schultheiss TE, Kun LE, Ang KK, Stephens LC: Radiation response of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31: 1093– 1112, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67). Sundgren PC, Fan X, Weybright P, Welsh RC, Carlos RC, Petrou M, McKeever PE, Chenevert TL: Differentiation of recurrent brain tumor versus radiation injury using diffusion tensor imaging in patients with new contrast-enhancing lesions. Magn Reson Imaging 24: 1131– 1142, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68). Ando K, Ishikura R, Nagami Y, Morikawa T, Takada Y, Ikeda J, Nakao N, Matsumoto T, Arita N: [Usefulness of Cho/Cr ratio in proton MR spectroscopy for differentiating residual/recurrent glioma from nonneoplastic lesions]. Nihon Igaku Hoshasen Gakkai Zasshi 64: 121– 126, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69). Aronen HJ, Perkiö J: Dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI of gliomas. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 12: 501– 523, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70). Covarrubias DJ, Rosen BR, Lev MH: Dynamic magnetic resonance perfusion imaging of brain tumors. Oncologist 9: 528– 537, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71). Ellika SK, Jain R, Patel SC, Scarpace L, Schultz LR, Rock JP, Mikkelsen T: Role of perfusion CT in glioma grading and comparison with conventional MR imaging features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28: 1981– 1987, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72). Sugahara T, Korogi Y, Tomiguchi S, Shigematsu Y, Ikushima I, Kira T, Liang L, Ushio Y, Takahashi M: Posttherapeutic intraaxial brain tumor: the value of perfusion-sensitive contrast-enhanced MR imaging for differentiating tumor recurrence from nonneoplastic contrast-enhancing tissue. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 21: 901– 909, 2000. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73). Di Chiro G, Oldfield E, Wright DC, De Michele D, Katz DA, Patronas NJ, Doppman JL, Larson SM, Ito M, Kufta CV: Cerebral necrosis after radiotherapy and/or intraarterial chemotherapy for brain tumors: PET and neuropathologic studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 150: 189– 197, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74). Doyle WK, Budinger TF, Valk PE, Levin VA, Gutin PH: Differentiation of cerebral radiation necrosis from tumor recurrence by [18F]FDG and 82Rb positron emission tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr 11: 563– 570, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75). Glantz MJ, Hoffman JM, Coleman RE, Friedman AH, Hanson MW, Burger PC, Herndon JE, Meisler WJ, Schold SC: Identification of early recurrence of primary central nervous system tumors by [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Ann Neurol 29: 347– 355, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76). Kim EE, Chung SK, Haynie TP, Kim CG, Cho BJ, Podoloff DA, Tilbury RS, Yang DJ, Yung WK, Moser RP: Differentiation of residual or recurrent tumors from post-treatment changes with F-18 FDG PET. Radiographics 12: 269– 279, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77). Ogawa T, Kanno I, Shishido F, Inugami A, Higano S, Fujita H, Murakami M, Uemura K, Yasui N, Mineura K: Clinical value of PET with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and L-methyl-11C-methionine for diagnosis of recurrent brain tumor and radiation injury. Acta Radiol 32: 197– 202, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78). Valk PE, Budinger TF, Levin VA, Silver P, Gutin PH, Doyle WK: PET of malignant cerebral tumors after interstitial brachytherapy. Demonstration of metabolic activity and correlation with clinical outcome. J Neurosurg 69: 830– 838, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79). Gómez-Río M, Rodríguez-Fernández A, Ramos-Font C, López-Ramírez E, Llamas-Elvira JM: Diagnostic accuracy of 201Thallium-SPECT and 18F-FDG-PET in the clinical assessment of glioma recurrence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35: 966– 975, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80). Kahn D, Follett KA, Bushnell DL, Nathan MA, Piper JG, Madsen M, Kirchner PT: Diagnosis of recurrent brain tumor: value of 201Tl SPECT vs 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163: 1459– 1465, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81). Olivero WC, Dulebohn SC, Lister JR: The use of PET in evaluating patients with primary brain tumours: is it useful? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 58: 250– 252, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82). Ricci PE, Karis JP, Heiserman JE, Fram EK, Bice AN, Drayer BP: Differentiating recurrent tumor from radiation necrosis: time for re-evaluation of positron emission tomography? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 19: 407– 413, 1998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83). Stokkel M, Stevens H, Taphoorn M, Van Rijk P: Differentiation between recurrent brain tumour and post-radiation necrosis: the value of 201Tl SPET versus 18F-FDG PET using a dual-headed coincidence camera—a pilot study. Nucl Med Commun 20: 411– 417, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84). Meller J, Sahlmann CO, Scheel AK: 18F-FDG PET and PET/CT in fever of unknown origin. J Nucl Med 48: 35– 45, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85). Miyatake S, Kuroiwa T, Kajimoto Y, Miyashita M, Tanaka H, Tsuji M: Fluorescence of non-neoplastic, magnetic resonance imaging-enhancing tissue by 5-aminolevulinic acid: case report. Neurosurgery 61: E1101– E1103; discussion E1103–E1104, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86). Wang SX, Boethius J, Ericson K: FDG-PET on irradiated brain tumor: ten years' summary. Acta Radiol 47: 85– 90, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87). Hung GU, Tsai SC, Lin WY: Extraordinarily high F-18 FDG uptake caused by radiation necrosis in a patient with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clin Nucl Med 30: 558– 559, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88). Ceyssens S, Van Laere K, de Groot T, Goffin J, Bormans G, Mortelmans L: [11C]methionine PET, histopathology, and survival in primary brain tumors and recurrence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 27: 1432– 1437, 2006. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89). Tsuyuguchi N, Takami T, Sunada I, Iwai Y, Yamanaka K, Tanaka K, Nishikawa M, Ohata K, Torii K, Morino M, Nishio A, Hara M: Methionine positron emission tomography for differentiation of recurrent brain tumor and radiation necrosis after stereotactic radiosurgery—in malignant glioma. Ann Nucl Med 18: 291– 296, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90). Miyashita M, Miyatake S, Imahori Y, Yokoyama K, Kawabata S, Kajimoto Y, Shibata MA, Otsuki Y, Kirihata M, Ono K, Kuroiwa T: Evaluation of fluoride-labeled boronophenylalanine-PET imaging for the study of radiation effects in patients with glioblastomas. J Neurooncol 89: 239– 246, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91). Miyatake S, Kawabata S, Nonoguchi N, Yokoyama K, Kuroiwa T, Matsui H, Ono K: Pseudoprogression in boron neutron capture therapy for malignant gliomas and meningiomas. Neuro-oncology 11: 430– 436, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92). Furuse M, Nonoguchi N, Kawabata S, Yoritsune E, Takahashi M, Inomata T, Kuroiwa T, Miyatake S: Bevacizumab treatment for symptomatic radiation necrosis diagnosed by amino acid PET. Jpn J Clin Oncol 43: 337– 341, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93). Mou YG, Sai K, Wang ZN, Zhang XH, Lu YC, Wei DN, Yang QY, Chen ZP: Surgical management of radiation-induced temporal lobe necrosis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: report of 14 cases. Head Neck 33: 1493– 1500, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94). Drappatz J, Schiff D, Kesari S, Norden AD, Wen PY: Medical management of brain tumor patients. Neurol Clin 25: 1035– 1071, ix, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95). Shaw PJ, Bates D: Conservative treatment of delayed cerebral radiation necrosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 47: 1338– 1341, 1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96). Glantz MJ, Burger PC, Friedman AH, Radtke RA, Massey EW, Schold SC: Treatment of radiation-induced nervous system injury with heparin and warfarin. Neurology 44: 2020– 2027, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97). Bui QC, Lieber M, Withers HR, Corson K, van Rijnsoever M, Elsaleh H: The efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of radiation-induced late side effects. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 60: 871– 878, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98). Chuba PJ, Aronin P, Bhambhani K, Eichenhorn M, Zamarano L, Cianci P, Muhlbauer M, Porter AT, Fontanesi J: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for radiation-induced brain injury in children. Cancer 80: 2005– 2012, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99). Kohshi K, Imada H, Nomoto S, Yamaguchi R, Abe H, Yamamoto H: Successful treatment of radiation-induced brain necrosis by hyperbaric oxygen therapy. J Neurol Sci 209: 115– 117, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100). Ohguri T, Imada H, Kohshi K, Kakeda S, Ohnari N, Morioka T, Nakano K, Konda N, Korogi Y: Effect of prophylactic hyperbaric oxygen treatment for radiation-induced brain injury after stereotactic radiosurgery of brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 67: 248– 255, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101). Gonzalez J, Kumar AJ, Conrad CA, Levin VA: Effect of bevacizumab on radiation necrosis of the brain. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 67: 323– 326, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102). Arratibel-Echarren I, Albright K, Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR: Use of Bevacizumab for neurological complications during initial treatment of malignant gliomas. Neurologia 26: 74– 80, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103). Boothe D, Young R, Yamada Y, Prager A, Chan T, Beal K: Bevacizumab as a treatment for radiation necrosis of brain metastases post stereotactic radio-surgery. Neuro-oncology 15: 1257– 1263, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104). Furuse M, Kawabata S, Kuroiwa T, Miyatake S: Repeated treatments with bevacizumab for recurrent radiation necrosis in patients with malignant brain tumors: a report of 2 cases. J Neurooncol 102: 471– 475, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105). Matuschek C, Bölke E, Nawatny J, Hoffmann TK, Peiper M, Orth K, Gerber PA, Rusnak E, Lammering G, Budach W: Bevacizumab as a treatment option for radiation-induced cerebral necrosis. Strahlenther Onkol 187: 135– 139, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106). Torcuator R, Zuniga R, Mohan YS, Rock J, Doyle T, Anderson J, Gutierrez J, Ryu S, Jain R, Rosenblum M, Mikkelsen T: Initial experience with bevacizumab treatment for biopsy confirmed cerebral radiation necrosis. J Neurooncol 94: 63– 68, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107). Levin VA, Bidaut L, Hou P, Kumar AJ, Wefel JS, Bekele BN, Grewal J, Prabhu S, Loghin M, Gilbert MR, Jackson EF: Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of bevacizumab therapy for radiation necrosis of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 79: 1487– 1495, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108). Lubelski D, Abdullah KG, Weil RJ, Marko NF: Bevacizumab for radiation necrosis following treatment of high grade glioma: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurooncol 115: 317– 322, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109). Gutin PH, Iwamoto FM, Beal K, Mohile NA, Karimi S, Hou BL, Lymberis S, Yamada Y, Chang J, Abrey LE: Safety and efficacy of bevacizumab with hypo-fractionated stereotactic irradiation for recurrent malignant gliomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 75: 156– 163, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110). Niyazi M, Ganswindt U, Schwarz SB, Kreth FW, Tonn JC, Geisler J, la Fougère C, Ertl L, Linn J, Siefert A, Belka C: Irradiation and bevacizumab in high-grade glioma retreatment settings. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82: 67– 76, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111). Miyatake S, Kawabata S, Hiramatsu R, Furuse M, Kuroiwa T, Suzuki M: Boron neutron capture therapy with bevacizumab may prolong the survival of recurrent malignant glioma patients: four cases. Radiat Oncol 9: 6, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]