Abstract

Setting: Malawi has chronic shortages of health workers, high burdens of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and malaria and a predominately rural population. Mobile health clinics (MHCs) could provide primary health care for adults and children in hard-to-reach areas.

Objectives: To determine the feasibility, volume, and types of services provided by three MHCs from 2011 to 2013 in Mulanje District, Malawi.

Design: Cross-sectional retrospective study.

Results: The MHCs conducted 309 492 visits for primary health care, and in 2013 services operated on 99% of planned days. Despite an improvement in service provision, overall patient visits declined over the study period. Malaria and respiratory and gastro-intestinal conditions constituted 60% of visits. Females (n = 11 543) significantly outnumbered males (n = 2481) tested for HIV, yet males tested HIV-positive (27%) more often than females (14%). Malaria accounted for 26 421 (35%) visits for children aged <5 years, with a significant increase in the rainy season. Implementation of rapid diagnostic testing was associated with a decline in numbers treated for malaria. Antibiotic stockouts at government clinics were associated with increased MHC visits.

Conclusion: MHCs can routinely provide primary health care for adults and children living in rural Malawi and complement fixed clinics. Moving from a complementary role to integration within the government health system remains a challenge.

Keywords: operational research, SORT IT, HIV testing, malaria, primary health care

Abstract

Cadre : Le Mialawi soufre d'un manque chronique de personnel de santé, d'un lourd fardeau d'infection au virus de l'mmuodéficience humaine (VIH) et de paludisme avec une population surtout rurale. Des unités de santé mobiles (MHCs) pourraient fournir des soins de santé primaires aux adultes et aux enfants dans les zones d'accès difficile.

Objectifs : Déterminer la faisabilité, le volume et les types de services fournis par trois MHCs de 2011 à 2013 dans le district de Mulanje, Malawi.

Schéma : Etude rétrospective transversale.

Résultats : Les MHCs ont effectué 309 492 consultations de soins de santé primaires et en 2013, les services ont fonctionné pendant 99% des jours prévus. En dépit d'une amélioration dans la fourniture des services, le total des consultations de patients a décliné au cours de la période d'étude. Le paludisme et les problèmes respiratoires et gastro-intestinaux constituaient 60% des consultations. Les femmes étaient significativement plus nombreuses (n = 11 543) que les hommes (n = 2481) à avoir un test VIH, mais les hommes étaient plus souvent VIH positifs (27%) que les femmes (14%). Le paludisme représentait 26 421 (35%) consultations pour les enfants de moins de 5 ans avec une augmentation significative en saison des pluies. La mise en œuvre des tests de diagnostic rapide a été associée à un déclin du nombre de patients traités pour paludisme. Les ruptures de stock d'antibiotiques dans les centres de santé du gouvernement étaient associés à une augmentation des consultations des MHC.

Conclusion : Les MHC peuvent offrir en routine des soins de santé primaires aux adultes et aux enfants vivant dans les zones rurales du Malawi et compléter les structures fixes. Mais passer d'un rôle de complément à l'intégration au sein du système de santé du gouvernement reste un défi.

Abstract

Marco de referencia: Malawi soporta una escasez crónica de personal sanitario, altas cargas de morbilidad por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) y el paludismo y su población es predominantemente rural. Los dispensarios ambulantes (MHC) podrían aportar atención primaria de salud a los adultos y los niños en las zonas de difícil acceso.

Objetivo: Examinar la factibilidad de la prestación de servicios ambulantes y determinar el volumen y los tipos de atención suministrados durante una intervención privada en tres MHC del 2011 al 2013 en el distrito de Mulanje, en Malawi.

Método: Fue este un estudio transversal retrospectivo.

Resultados: En los dispensarios ambulantes se practicaron 309 492 consultas de atención primaria y en el 2013, los servicios funcionaron durante el 99% de los días planeados. Pese a un progreso en la prestación de servicios, el número global de consultas disminuyó durante el período del estudio. El paludismo, las enfermedades respiratorias y gastrointestinales constituyeron el motivo de consulta en el 60% de los casos. Las mujeres fueron significativamente más numerosas que los hombres a practicar la prueba diagnóstica del VIH (11 543 contra 2481), pero los hombres obtuvieron con mayor frecuencia un resultado positivo (27% contra 14%). El paludismo correspondió a 26 421 consultas en los niños menores de 5 años de edad (35%) y se observó un aumento considerable en la temporada de lluvias. La ejecución de las pruebas diagnósticas rápidas se asoció con una disminución del número de pacientes tratados por paludismo. Los desabastecimientos de antibióticos en los consultorios gubernamentales se asociaron con un aumento en el número de consultas a los consultorios ambulantes.

Conclusión: Los MHC pueden suministrar atención sanitaria sistemática a los adultos y los niños que viven en las zonas rurales de Malawi y completar así la atención prestada por los consultorios fijos. La evolución de este sistema, de una función complementaria a su integración en los sistemas nacionales de salud, sigue siendo una tarea difícil.

In most low-income countries, access to affordable basic primary health care is limited. In Malawi, 84% of the population lives in rural villages, located far from fixed government health facilities.1 The distance that villagers travel to access health care adversely affects health-seeking behaviors and health outcomes, particularly in a country where the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is 10% and malaria incidence is 34 000 per 100 000 population annually.1,2 Only 46% of Malawians live within 5 km of a health facility.3 Deaths resulting from the acquired immune-deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are a major contributing factor to health care worker shortages and limit the capacity of the health system to deliver services.4,5 Government health facilities are chronically understaffed—51% of Ministry of Health (MOH) established health care worker positions were reported vacant in 2011.6 Moreover, a study by Oxfam in 2012 found that only 9% of local health facilities had the full essential health package of drugs, and that clinics were frequently out of basic antibiotics and HIV test kits.7

Although mobile health clinics (MHCs) often provide targeted health care services to vulnerable populations in both high- and low-income countries, limited evidence exists of their use and effectiveness in improving delivery of health services. In an attempt to increase the visibility of MHC utilization and its impact on the health care system, one study from the United States reviewed data from 1500 MHCs and found them to be effective in targeting hard-to-reach populations, in improving the care of chronic conditions, and in controlling health system costs.8 In low- and middle-income countries, MHCs are effective in screening for specific diseases such as HIV in South Africa and cervical cancer in Thailand and in treating targeted chronic conditions such as epilepsy in rural Malawi.9–11 MHCs have improved vaccination coverage and reduced parasite prevalence in children living in remote areas of Namibia, and they offer a means of extending access to primary health care for seasonal migratory workers in Turkey.12,13

From 2008 onwards, the Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance (GAIA) operated an MHC program to combat HIV, tuberculosis (TB), and malaria in Mulanje, Malawi, in conjunction with the Malawi MOH. Eighteen months after implementation, GAIA conducted an evaluation of implementation performance and challenges, and the program has since expanded the scope of services to include basic primary health care.14 A third MHC was launched in 2010. Beyond the preliminary evaluation of this program, there is no evidence to show that MHCs can continuously provide basic primary health care for both children and adults in Malawi. Such evidence has the potential to improve primary health care delivery in rural settings and inform deployment of additional MHCs, in both Malawi and other low-income countries in Africa.

The aim of this study was therefore to describe the feasibility of clinic operations and utilization of expanded services provided by the GAIA Elizabeth Taylor MHC program over a 3-year period from 2011 to 2013, with an in-depth review of HIV testing and malaria services. Specific objectives were to assess: 1) the feasibility of service provision; 2) the volume of services and utilization by type of service provided in relation to age and sex; 3) HIV testing and counseling, and administration of cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) for those who are HIV-positive; and 4) malaria screening and treatment.

METHODS

Design

The study was a cross-sectional analysis of retrospective data. The study describes routinely collected MHC data from January 2011 to December 2013, and data were analyzed from January to May 2014.

Setting

Malawi is located in Southern Africa, with a population of 16 million and a gross national income per capita of $320.1 In rural Mulanje District, with a population of 550 000, HIV prevalence is nearly double the national average at 17%, and the district is holoendemic for malaria. There is only one government hospital and 16 rural health facilities—many of which operate only 1–2 days per week—providing free health care, and one mission hospital and three mission health centers providing fee-for-service care. A shortage of district health personnel and frequent medication and supply stockouts are obstacles to obtaining basic health care. Vacancy rates remain high for clinical officers, at 76%, and for nursing officers, at 48%, in government and Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) facilities.6

To close the service gap for Malawian communities affected by HIV/AIDS, GAIA launched two MHCs in Mulanje District in 2008 with major funding from the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation. In 2010, GAIA launched a third MHC and increased the volume of services provided to address basic health care needs that were unmet by existing fixed clinics. The MHCs serve an estimated catchment population of 300 000 Malawians and Mozambicans.

Each MHC is fully funded by GAIA donors and staffed by a clinical officer, nurse, nurse aide, and driver. GAIA informs the community of MHC operations through radio, village leader networks, and community-based meetings. Each MHC visits five separate sites per week. Each clinic was intended to operate for 4 h, providing health talks and growth monitoring while an estimated 50 clients are seen, although up to 300 clients may be seen over 8–10 h during the rainy season.

MHCs conduct voluntary HIV testing in accordance with national policy and when the clinician feels it is indicated. Rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) are used to determine HIV serostatus, first with Determine (HIV-1/2 test, Abbott, IL, USA), and, for those found to be HIV-positive, the results are confirmed with Unigold (HIV-1, Trinity Biotech, Wicklow, Ireland). All HIV-positive clients receive CPT and are referred to the nearest hospital for antiretroviral therapy (ART) assessment. Before 2012, most clients were treated for clinical malaria based on history and symptoms using oral lume-fantrine-artemether or quinine injections. Since 2012, clinicians have investigated symptoms in all clients using a Paracheck-Pf (Orchid Biomedical Systems, Goa, India) RDT. Malaria treatment is targeted at those with a positive test result.

Study population

The study population included all visits to the MHCs from January 2011 to December 2013.

Data variables

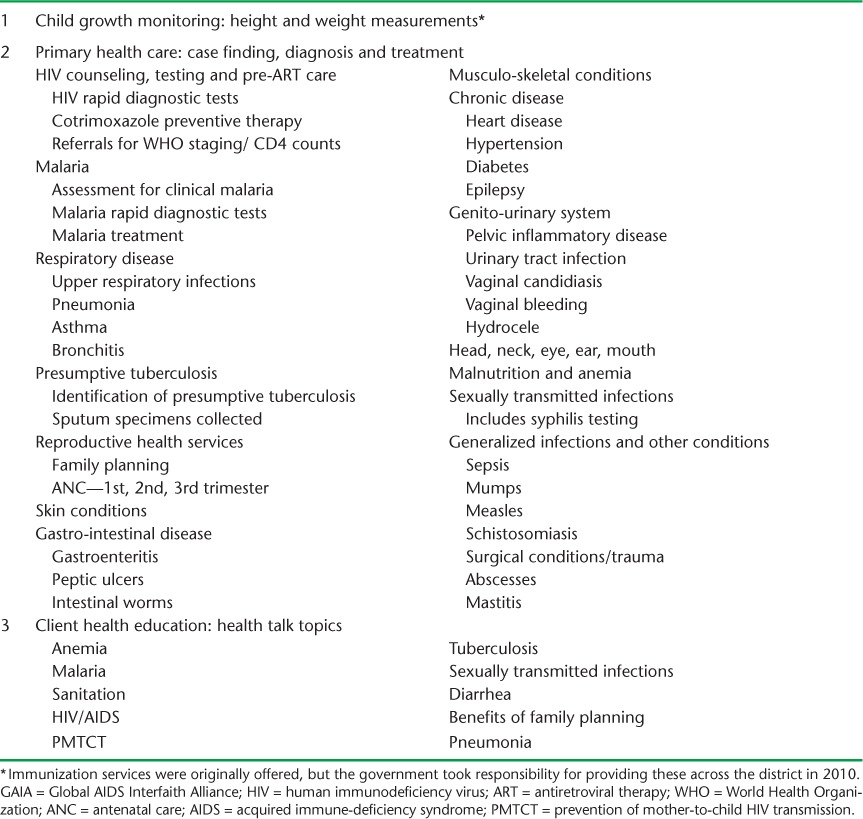

The preventive and curative health services offered at the MHCs include child growth monitoring, basic primary health care, and health education, detailed in Table 1. All staff, services, and supplies are funded directly by GAIA (with the exception of contraceptives, which are provided by the government). Data collected by clinic nurses are aggregated to summarize the services utilized at each clinic, by month, year, age group (under 5 years and over 5 years only), and sex (after 2011 for some services) for outcomes of interest. Data variables collected in this way include: clinic operating information, number of visits by type of service utilized, and conditions treated in relation to client age, sex, and month and year of the visit.

TABLE 1.

Preventive and curative care provided at the GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mulanje, Malawi

Analysis

Data were imported into Stata (Stata/SE11.2, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) from the Excel® database (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA). Summary statistics and t-tests were generated in Stata to determine whether the variable of interest, service utilization, was associated with year of service provision, age group, and sex, with differences at the 5% level being regarded as significant. Excel was used for time-trend analysis and graphical representation.

Ethics

The National Health Science and Research Committee of Malawi deemed this study exempt from ethics approval. The study met the Médecins Sans Frontières, Geneva, Switzerland, Ethics Review Board-approved criteria for analysis of routinely-collected program data. It also received approval from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France.

RESULTS

Feasibility of service provision

Data on clinic operating days were available for 2012 and 2013. In 2012, MHCs operated for 675 (93%) of the expected 723 clinic days. Missed days were due to planning meetings (n = 24), vehicle servicing (n = 10), death of a clinical officer and a national day of mourning for the president's death (n = 9), and countrywide fuel shortages (n = 5). In 2013, as a result of implementation changes, MHCs operated for 722 (99%) of 729 days, with missed days due to planning meetings (n = 6) and weather-related road conditions (n = 1).

Volume and types of service utilized

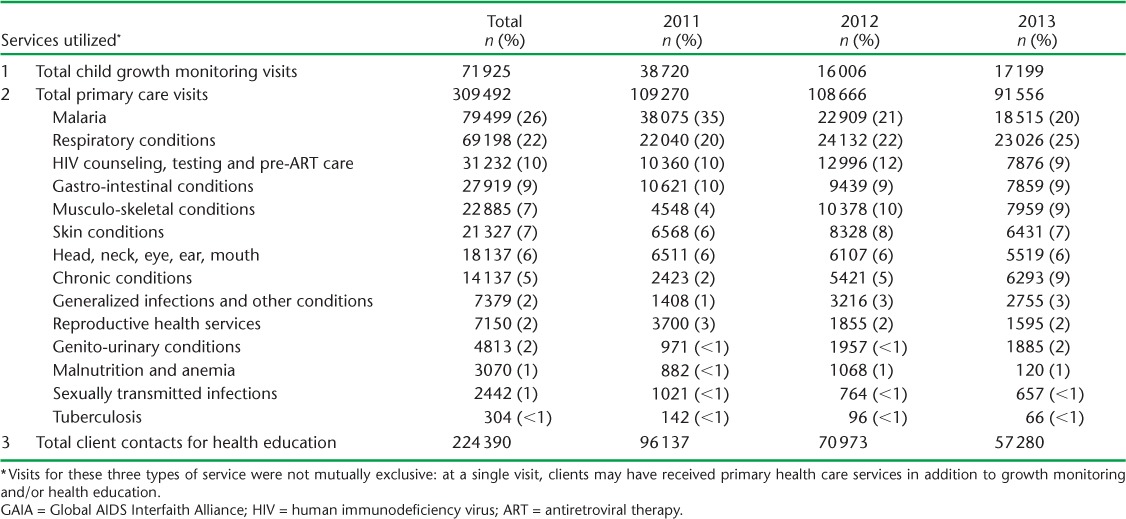

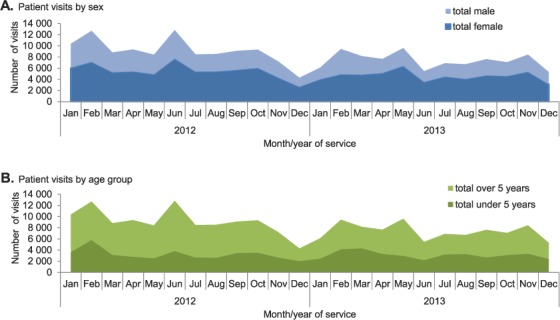

The overall total and annual utilization of the three types of MHC services are shown in Table 2. There was an average of over 100 000 client visits per year for primary health care, of which 75% were paired with health education. In children aged <5 years, primary health care visits often included child growth monitoring. For all types of service, there was a decline from 2011 to 2013; this was mirrored by client visits per day, which also decreased from a mean of 174 in 2011 to 162 in 2012 and 123 in 2013. Malaria and respiratory and gastro-intestinal disease were the most common conditions, accounting for nearly 60% of total primary health care visits. Monthly client visits by sex and age group from 2012 to 2013 are shown in Figure 1. Significantly more females utilized services every month (P < 0.001), accounting for 62% of all client visits. Children aged <5 years accounted for 39% of total client visits.

TABLE 2.

Preventive and curative care services utilized at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mulanje, Malawi, 2011–2013

FIGURE 1.

Monthly client visits by A) sex and B) age group at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mu-lanje, Malawi, 2012–2013. GAIA = Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance.

HIV testing, counseling and cotrimoxazole preventive therapy

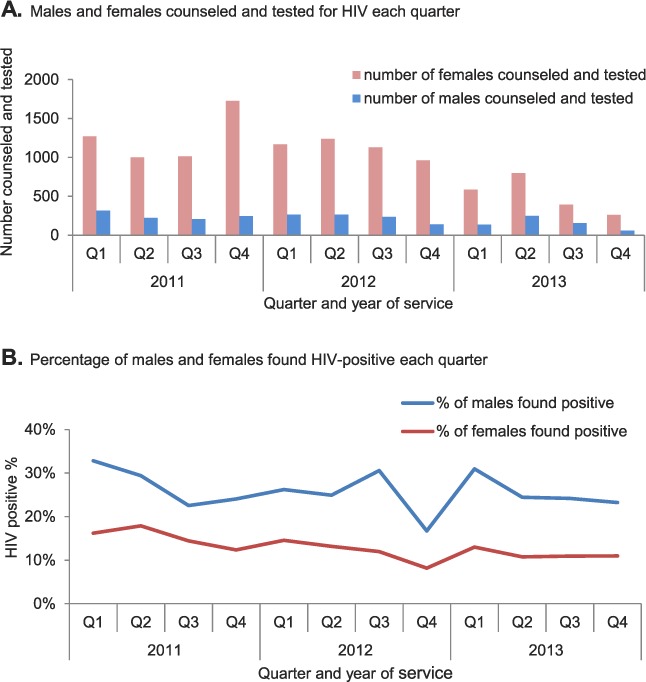

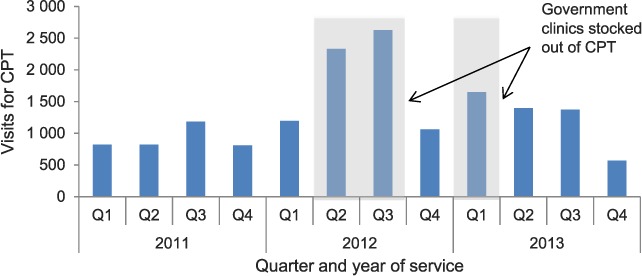

In the 3-year period, 14 024 HIV tests were carried out, 11 543 (82%) of which were among females. Figure 2 shows quarterly trends in visits for HIV testing and counseling along with the results. Numbers tested for HIV were similar in the first two years but declined in the third year, although visits for HIV counseling, testing, and pre-ART care represented roughly the same proportion of annual visits, between 9% and 12%. In each quarter, significantly more females than males were tested for HIV (P < 0.001). In contrast, in each quarter significantly more males were found to be HIV-positive (P < 0.001): in total, 27% of males were HIV-positive compared with 14% of females. Figure 3 shows quarterly visits for CPT. The two periods when client visits for CPT were high coincided with stockouts of CPT in government clinics.

FIGURE 2.

A) Males and females counseled and tested for HIV and B) percentage found positive at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mulanje, Malawi, 2011–2013. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; GAIA = Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance.

FIGURE 3.

Number of client visits for administration of CPT at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mulanje, Malawi, 2011–2013. GAIA = Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance; CPT = cotrimoxazole preventive therapy.

Malaria screening and treatment

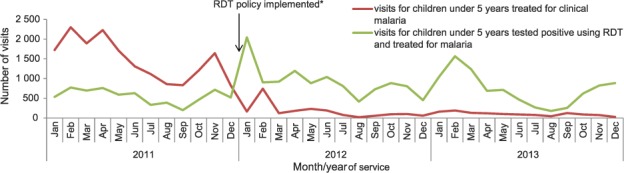

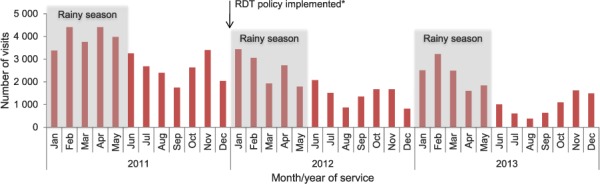

Of the 76 294 MHC visits in the 3-year period for children aged <5 years, 26 421 (35%) were for malaria diagnosis and treatment. Monthly visits for these children are shown in Figure 4. There was an overall decline in the total number of visits during the 3 years. With the implementation of the RDT policy, there was a significant decline in the number of patients treated for clinical malaria and a significant increase in treatment of RDT-positive malaria in 2012 compared with 2011 (P < 0.001). Figure 5 illustrates the monthly visits to the clinics for both adults and children treated for malaria. In each year, there were significantly more visits for malaria treatment during the rainy season months of January to May (2011 and 2013 P < 0.001; 2012 P < 0.003).

FIGURE 4.

Visits for children aged <5 years treated for clinical malaria and RDT-positive malaria at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Clinics, Mulanje, Malawi, 2011–2013. * GAIA Elizabeth Taylor mobile clinics implemented a policy of RDT for malaria for all children aged <5 years with suspected malaria. GAIA = Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance; RDT = rapid diagnostic testing.

FIGURE 5.

Number of visits (adults and children) each month for malaria treatment at GAIA Elizabeth Taylor mobile clinics, Mulanje, Malawi, 2011–2013. * GAIA Elizabeth Taylor mobile clinics implemented a policy of RDT for malaria for all children aged <5 years with suspected malaria. GAIA = Global AIDS Interfaith Alliance; RDT = rapid diagnostic testing.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report on the use of MHCs in providing routine primary health care for adults and children in a rural district of Malawi. The study had four main findings. First, the MHCs conducted an average of 153 client visits per clinic per day, the majority for the diagnosis and management of malaria and respiratory and gastrointestinal conditions, and for HIV testing. Females accessed these services more frequently than males, and children aged <5 years constituted 40% of visits. Health talk attendance decreased as overall client visits decreased, and this decrease coincided with client triaging procedures which reduced the need to arrive early, when the health talks would take place, to queue for care. Child growth monitoring visits decreased as the government introduced outreach clinics in 2012 to combat child malnutrition and stunting. As reproductive health care services and TB screening were increasingly offered by the fixed government clinics over the study period, utilization declined at the MHCs.

Second, significantly more females were tested for HIV compared with males. This parallels trends in national reports on HIV testing and counseling, and illustrates a general problem of low uptake of HIV testing by males.15 Males tested at MHCs had nearly double the HIV-positive rate of females, suggesting an urgent need to increase the male uptake of HIV testing and counseling.

Third, yearly quarters associated with high provision of CPT coincided with stockouts in government fixed clinics, showing that MHCs complement fixed facilities and fill a service provision gap.15,16 CPT is an important part of HIV/AIDS care, used for both pre-ART and as an adjunct for those on ART, and drug interruptions compromise quality of care and threaten survival.17

Fourth, visits for malaria diagnosis and treatment constituted over one third of under-five visits. Malaria is an important public health problem in Malawi, fluctuates seasonally, as shown by increased MHC visits in the rainy season, and is responsible for a large number of childhood deaths. Before 2012, malaria in Malawi was generally managed empirically, resulting in significant over-treatment. For example, only 2% of rural fixed health centers used RDTs to diagnose malaria in 2011.18 Malawi subsequently recommended the use of RDT in all clients with suspected malaria, with treatment targeted to those shown to be RDT-positive.19 The findings from MHCs showed a marked decrease in numbers of all clients being treated for malaria after this policy change. This may indicate a more rational use of anti-malarial treatment and facilitates further investigation in febrile clients without confirmed malaria.

The strengths of this study were the large catchment area served by MHCs, the long period of observation, and the closely monitored and comprehensive record keeping. Furthermore, this observational study adhered to Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.20 The main limitations, which were outside the scope of this study, were the lack of comparative data from fixed clinics in the district, the lack of qualitative data to explain the overall decline in client visits, and lower male participation, which limited analysis to trends in relation to season, age, and sex.

The study has several policy and practice implications. First, the continuity of the MHC services improved between 2012 and 2013 due to servicing of vehicles and organizing of planning meetings on weekends. Real-time accurate data on service continuity and feasibility can be used by management to inform and improve program implementation. Second, it is clear that MHCs complement the work of fixed government clinics through, for example, filling gaps in treatment when there are drug stockouts, rapidly implementing and monitoring changes in government health policy, and expanding access to health care for hard-to-reach communities. More, however, needs to be done to integrate complementary MHC services into the government health system and district health office budgets and to include MHC client data in district level databases. District level data from the next Malawi Demographic and Health Survey could also be used to analyze trends in child mortality due to malaria and pneumonia, which are routinely treated at the MHCs. Third, qualitative research is needed to understand and possibly resolve low MHC service utilization by males. The cost-effectiveness of the MHC approach should also be formally investigated.

In conclusion, we have shown that primary health care for large numbers of adults and children can be provided by non-governmental organizations on a routine basis through MHCs in a rural district of Malawi with limited resources. The most important challenge ahead is how best to integrate MHCs with public health sector services to target the most underserved populations.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). The specific SORT IT program that resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by: the Operational Research Unit (LUXOR), MSF, Brussels Operational Centre, Luxembourg; the Centre for Operational Research, The Union, Paris, France; The Union South-East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi, India; and the Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Norway.

The SORT IT program was funded by MSF, The Union, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the WHO. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The GAIA Elizabeth Taylor Mobile Health Clinics have been funded by the Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation since the program's inception in 2008.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

In accordance with WHO's open-access publication policy for all work funded by the WHO or authored/co-authored by WHO staff members, the WHO retains the copyright of this publication through a Creative Commons Attribution IGO license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode) which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

References

- 1.World Bank. Data: Malawi. Washington, USA: World Bank; 2014. http://data.worldbank.org/country/malawi Accessed October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Malawi. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2013. http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/malawi/ Accessed October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Second Generation, World Health Organization Country Cooperation Strategy, 2008–2013, Malawi. Brazzaville, Republic of Congo: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harries A D, Hargreaves N J, Gausi F, Kwanjana J H, Salaniponi F M. High death rates in health care workers and teachers in Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96:34–37. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90231-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Makombe S D, Jahn A, Tweya H et al. A national survey of the impact of rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy on health-care workers in Malawi: effects on human resources and survival. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:851–857. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malawi Ministry of Health. Health workforce optimization analysis: optimal health worker allocation for public health facilities across Malawi. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health and Clinton Health Access Initiative; 2011. https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/Malawi%20HRH%20Optimization%20Analysis%20Report.pdf Accessed October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxfam. Missing Medicines in Malawi: campaigning against ‘stock-outs’ of essential drugs. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxfam; 2012. http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/missing-medicines-in-malawi-campaigning-against-stock-outs-of-essential-drugs-226732 Accessed October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill C F, Powers B W, Jain S H et al. Mobile health clinics in the era of reform. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bassett I, Regan S, Luthuli P et al. Linkage to care following community-based mobile HIV testing compared with clinic-based testing in Umlazi Township, Durban, South Africa. HIV Med. 2013;15:367–372. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12115. Epub 2013 Nov 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swaddiwudhipong W, Chaovakiratipong C, Nguntra P, Mahasakpan P, Tatip Y, Boonmak C. A mobile unit: an effective service for cervical cancer screening among rural Thai women. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:35–39. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watts A E. A model for managing epilepsy in a rural community in Africa. BMJ. 1989;298:805–807. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aneni E, De Beer I H, Hanson L, Rijnen B, Brenan A T, Feeley F G. Mobile primary healthcare services and health outcomes of children in rural Namibia. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13:2380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simsek Z, Koruk I, Doni N Y. An operational study on implementation of mobile primary healthcare services for seasonal migratory farmworkers, Turkey. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16:1906–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindgren T G, Deutsch K, Schell E et al. Using mobile clinics to deliver HIV testing and other basic health services in rural Malawi. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11:1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malawi Ministry of Health. Government of Malawi Integrated HIV Program Report, April–June 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malawi Ministry of Health. Government of Malawi Integrated HIV Program Report, January–March 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowrance D, Makombe S, Harries A et al. Lower early mortality rates among patients receiving antiretroviral treatment at clinics offering cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;1:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinhardt L C, Chinkhumba J, Wolkon A et al. Quality of malaria case management in Malawi: results from a nationally representative health facility survey. PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e89050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malawi Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health guidelines for use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (mRDTs) Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, Pocock S J, Gøtzsche P C, Vandenbroucke J P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;147:573–578. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]