Abstract

Background:

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is a heterogenous collection of signs and symptoms that when gathered, form a spectrum of disorder with disturbance of reproductive, endocrine and metabolic functions.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to correlate the skin manifestations with hormonal changes and to know the incidence and prevalence of skin manifestations in patients with PCOS.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 40 patients with PCOS were examined during 1 year time period from May 2008 P to May 2009. Detailed clinical history was taken from each patient. PCOS was diagnosed on the basis of ultrasonography. Hormonal assays included fasting blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, thyroid stimulating hormone, dehydroepiandrostenedione, prolactin, free testosterone, fasting lipid profile and sex hormone binding globulin. The results obtained were statistically correlated.

Results:

In our study, the prevalence of cutaneous manifestations was 90%. Of all the cutaneous manifestations acne was seen in highest percentage (67.5%), followed by hirsutism (62.5%), seborrhea (52.5%), androgenetic alopecia (AGA) (30%), acanthosis nigricans (22.5%) and acrochordons (10%). Fasting insulin levels was the most common hormonal abnormality seen in both acne and hirsutism, whereas AGA was associated with high testosterone levels.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of cutaneous manifestations in PCOS was 90%. Hirsutism, acne, seborrhea, acanthosis nigricans and acrochordons were associated with increased levels of fasting insulin, whereas AGA showed higher levels of serum testosterone.

Keywords: Cutaneous manifestations, hormonal changes, polycystic ovarian syndrome

What was known?

Previously, it was known that only females in post-menopausal age group were at a greater risk for developing cardiovascular disorders and hence monitoring for the same would start only at a later time period.

Introduction

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is an endocrine disorder that affects approximately 5-10% of all women of reproductive age.[1] In 1935, Stein and Levinthalfirst described the association between polycystic ovaries, amenorrhea, hirsutism and obesity.[2]

The morphology of the polycystic ovary has been redefined as an ovary with 12 or more follicles measuring 2-9 mm in diameter and/or increased ovarian volume (>10 cm3).[3] The fundamental ovarian hormonal and functional abnormalities that accompany PCOS are infrequent or absent ovulation, infrequent or absent secretion of progesterone, increased secretion of male hormones, persistent estrogen secretion, increased luteinizing hormone secretion, insulin resistance and cystic ovaries.[4]

It is characterized by hyperandrogenism, menstrual abnormality, infertility, obesity, diabetes mellitus and hirsutism with skin changes and abnormalities of biochemical profile including increased serum (LH), testosterone, androstenedione and insulin.[5]

The pathophysiology of PCOS appears to be multifactorial and polygenic. The main pathophysiology points to the ovary being the source of excess androgens, which appears to result from an abnormal regulation of steroidogenesis.[6]

The excessive secretion of androgens in PCOS patients results in a series of skin changes including hirsutism, acne, seborrhea and androgenetic alopecia.[7] These all originate in the pilosebaceous unit, the common skin structure that gives rise to both hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The other cutaneous changes are acanthosis nigricans and achrocordons.

At a joint European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology/American Society for Reproductive Medicine consensus meeting in 2003, a refined definition of PCOS was agreed, namely the presence of two out of the following three criteria:[8]

Oligo and/or anovulation

Hyper androgenism (clinical and/or biochemical)

Polycystic ovaries with the exclusion of other etiologies.

The aim of our study is to find the incidence and prevalence of dermatological manifestations as well as the correlation of the hormonal changes with dermatological changes in patients of PCOS.

Materials and Methods

A total of 40 patients with PCOS who attended out-patient department at care institute of medical sciences from May 2008 to May 2009 were included in the study after obtaining consent and ethics committee approval.

Inclusion criteria of PCOS are Oligo OR anovulation, hyperandrogenism biochemical evidence of androgen excess, polycystic ovaries as defined by ultrasonography, females in reproductive age group.

Exclusion criteria: Included other pathological conditions of hormonal imbalance such as ovarian virilizing tumor, adrenal tumor, late onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing's syndrome, hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia.

Details of clinical, menstrual and obstetric history were taken from each patient.

Cutaneous manifestations were noted down on the basis of its clinical appearance as acne, hirsutism, AGA, seborrhea, acanthosis nigricans and acrochordons. PCOS was diagnosed based on ultrasonography when ovary showed 12 or more follicles measuring 2-9 mm in diameter or a total ovarian volume of > 10 cm3.

Hormonal assays such as – follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), LH, sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), dehydroepiandrostenedione (DHEA-S), prolactin and free testosterone levels on the 2nd day of the menstrual cycle.

Other hormonal assays included were fasting blood sugar, postprandial blood sugar, fasting lipid profile, fasting insulin levels and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

FSH and LH levels were assessed in the serum and plasma using electrochemiluminescent assay. Quantitative determination of human TSH levels in serum and plasma was done using the access hypersensitive hTSH assay, T3 and T4 levels were assayed using access total T3 and T4 assay, which is a form of chemiluminescent assay. Testosterone and DHEA-S levels were measured using access immunoassay systems.

Statistical analysis

Patients were included on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria as elaborated above. The measures of central tendency were calculated by using mean. The measures of dispersion were calculated using standard deviation. All variables were tabulated using Microsoft Excel package.

Results

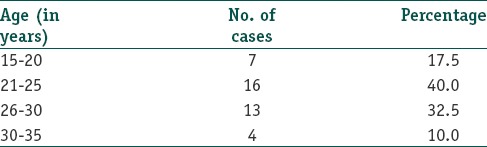

The total number of patients evaluated as seen from Table 1 are 40, out of which 16 patients were in the age group of 21-25 (40%), 13 patients were in the age group of 26-30 (32.5%). Among patients participated in our study most of the them were in the age group of 21-30 years (72.5%).

Table 1.

Number of patients studied and their percentages in different age group

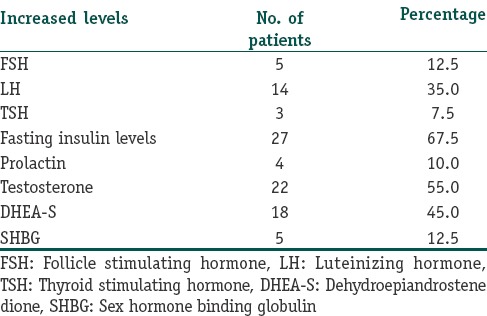

Table 2 shows the increased levels of hormones and their respective percentages in patients. As seen by the table most common hormonal abnormality encountered was rise in fasting insulin levels (67.5%).

Table 2.

Increased levels of hormones and their respective percentages in patients

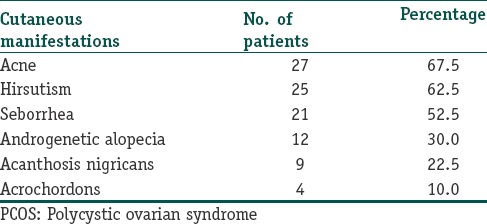

Table 3 shows the cutaneous manifestations and their frequencies. amongst the cutaneous manifestations in patients with PCOS acne vulgaris topped the list with 27 patients (67.5%) showing acne, followed closely by hirsutism in 25 (62.5%) patients, seborrhea was seen in 21 (52.5%) patients, AGA in 12 (30%) patients, acanthosis nigricans in 9 (22.5%) patients and acrochordons in 4 (10%) of patients.

Table 3.

Cutaneous manifestations and their frequencies in PCOS patients

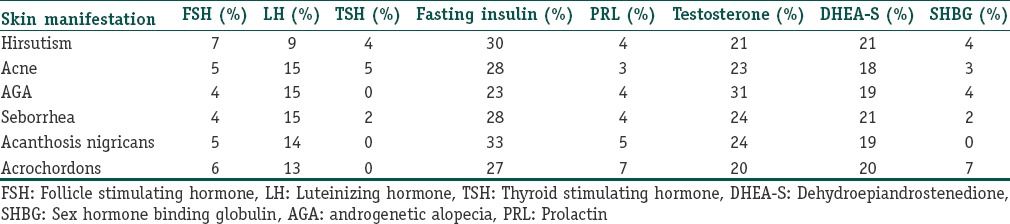

Table 4 shows the correlation of skin changes with hormonal changes. Hirsutism was associated with increased fasting insulin in 30%, serum testosterone in 21%, DHEA-S in 21%, LH in 9%.

Table 4.

Correlation of skin changes with increased hormone levels

Acne was associated with increase in fasting insulin in 28%, testosterone in 23%, DHEA-S in 18%, LH in 15%. AGA showed increase in testosterone by 31%, fasting insulin by 23%, DHEA-S by 19%. Seborrhea showed increase in fasting insulin by 28%, testosterone by 24% and DHEA-S in 21%. Acanthosis nigricans showed increased fasting level insulin in 33%, increased testosterone in 24% and DHEA-S in 19%. In patients with acrochordons 27% had a rise in fasting insulin levels, 20% showed rise in both testosterone and DHEA-S.

Discussion

PCOS is the most common endocrinopathy in women of reproductive age characterized by chronic anovulation/infrequent ovulation, obesity, hirsutism, hyperandrogenism and numerous follicular cysts in the enlarged ovaries. In recent years, it has become apparent that PCOS is also associated with characteristic metabolic disturbances that may have implications for long-term health. The pathophysiology of PCOS appears to be multifactorial and polygenic. The main pathophysiology points to the ovary being the excess source of androgens, which appears to result from an abnormal regulation of steroidogenesis.[6] The risk of developing PCOS is partly genetic and disturbance in insulin metabolism plays a key role. Insulin gene variable number of tandem repeats class II allele was associated with PCOS and showed strong correlation with anovulatory PCOS.[9] The steroidogenic response to the trophic hormone is modulated by an array of small peptides, which include insulin and insulin like growth factors, insulin also augments LH stimulated androgen production via its receptors.[10] Insulin acts through multiple sites to increase endogenous androgen levels, excess insulin binds to insulin growth factor-1 receptors, which enhances the theca cell androgen production in response to LH stimulation, hyperinsulinemia also decreases the synthesis of sex hormone binding globulin by the liver further increasing the androgen levels.[11]

Genetic studies have also identified a link between PCOS and disordered insulin metabolism.[12] Lack of ovulation and infrequent menstrual periods, which is the centrecenter of disturbed pathophysiology in PCOS is caused by infrequent release of progesterone hormone and excess estrogen levels.[4]

Excess androgen production by ovary and occasionally by adrenal glands is responsible for the cutaneous changes such as acne, seborrhea, AGA and hirsutism.[4]

In our study of 40 patients who were diagnosed with PCOS according to the criteria, the prevalence of cutaneous manifestations was 90%. Among the study group 72.5% (29) were n the age group of 21-30 years, which was comparable with the studies carried out by Sharma et al.,[13] Majumdar and Singh,[14] Wijayaratne et al.,[15] Tayob et al.,[16] this shows that PCOS in Indian females set at an early age.

The prevalence of obesity, which is about 32.5% in our study was comparable with studies conducted by Majumdar and Singh,[14] Sundaraman et al.,[17] Balen et al.,[3] Cresswell et al.[18] which showed similar results.

In our study, acne was the most common cutaneous manifestation in patients with PCOS followed by hirsutism, seborrhea, AGA, acanthosis nigricans and acrochordons in decreasing order of frequency, which was comparable with the studies conducted by Sharma et al.,[13] Majumdar and Singh,[14] Dramusic et al.[19] and Bunker et al.[20,21] which also showed that acne was the most common cutaneous manifestation in PCOS group, but the prevalence rates of hirsutism was found at lower rates by Majumdar and Singh[14] and Sundararaman et al.[17]

In our study of the hormonal changes, high fasting insulin levels were seen in 27 (67.5%) patients, which accounts for the highest percentage change. An increased level of serum testosterone was seen in 22 (55%) patients; whereas increased levels of DHEA-S was seen in 15 (45%) of patients. Similarly, increased LH was seen in 14 (35%) patients; increased LH/FSH ratio was seen in 11 (27.5%) patients, increased levels of SHBG was seen in 5 (12.5%) patients; increased FSH in 5 (12.5%) and increased prolactin levels in 4 (10%) patients.

PCOS is a heterogenous, familial condition. Ovarian dysfunction leads to the main signs and symptoms. Ovary is influenced by external factors in particular the gonadotrophins, insulin and other growth factors, which are dependent upon both genetic and environmental influences. There are long-term risks of developing diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases, therapy to date has been symptomatic, but by our improved understanding of the pathogenesis, treatment options are becoming available that strike more at the heart of the syndrome.

Westernization, urbanization and mechanization, which are the hallmarks of development in our country, are the factors that affect expression and presentation of PCOS. In our country, as the prevalence rates was found higher in the younger age group it is important to identify and treat the problem at a younger presenting age and henceforth combat the adverse metabolic effects, which would present much later in life.

PCOS is probably the same world over; although, there may be many factors that affect expression and presentation. Considering the unique structure of Indian population, it is imperative that more studies of relation between hormones and PCOS should be conducted so as to pave way for suitable medical interventions. This emphasizes the importance of studying the incidence and prevalence of dermatological manifestations as well as the correlation of hormonal changes with dermatological changes in patients of PCOS.

A review of the literature indicates that there are no studies correlating the hormonal changes in PCOS with cutaneous manifestations. In our study, we found that skin manifestations in Indian women with PCOS account for 90% with hirsutism, acne, seborrhea, acanthosis nigricans and acrochordons associating with increased levels of fasting insulin whereas manifestations like AGA showing higher levels of serum (4) testosterone. It is therefore imperative for the treating physicians to understand the adverse metabolic effects associated with PCOS and recognize these potential health risks in patients and treat them accordingly.

Our study being a small series statistical comparison could not be performed; hence, our observations need further confirmation in a larger prospective controlled study.

What is new?

From our study, it shows that PCOS should be considered as a metabolic syndrome and since females at a younger age group are showing to be at higher risk for developing cardiovascular disorders, monitoring for the same should start at an earlier age to reduce the morbidity.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Kathe G. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [Last accessed 2013 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.Revolutionhealth.com/londitireproductivehealth/infertility/female-cause PCOS .

- 2.Stein IF, Levinthal MI. Amenorrhea associated with bilateral polycystic ovaries. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 1935;29:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balen AH, Laven JS, Tan SL, Dewailly D. Ultrasound assessment of the polycystic ovary: International consensus definitions. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:505–14. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.William N, Burns WN. Patient information: Polycystic ovary syndrome – Disease process and treatment. [Last accessed on 2015 Jun 26]. Available from: http://marshallhealth.org/media/19971/PolycysticOvarySyndrome.pdf .

- 5.Conway GS, Honour JW, Jacobs HS. Heterogeneity of the polycystic ovary syndrome: Clinical, endocrine and ultrasound features in 556 patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1989;30:459–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1989.tb00446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenfield RL, Barnes RB, Cara JF, Lucky AW. Dysregulation of cytochrome P450c 17 alpha as the cause of polycystic ovarian syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:785–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balen AH, Conway GS, Kaltsas G, Techatrasak K, Manning PJ, West C, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome: The spectrum of the disorder in 1741 patients. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2107–11. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-Sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) Hum Reprod. 2004;19:41–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterworth DM, Bennett ST, Gharani N, McCarthy MI, Hague S, Batty S, et al. Linkage and association of insulin gene VNTR regulatory polymorphism with polycystic ovary syndrome. Lancet. 1997;349:986–90. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balen AH, Conway GS, Homburg R, Legro RS. Oxfordshire: Taylor and Francis; 2005. Polycystic ovary syndrome: A guide to clinical management. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergh C, Carlsson B, Olsson JH, Selleskog U, Hillensjö T. Regulation of androgen production in cultured human thecal cells by insulin-like growth factor I and insulin. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55675-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franks S, Gharani N, McCarthy M. Candidate genes in polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:405–10. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma NL, Mahajan VK, Jindal R, Gupta M, Lath A. Hirsutism: Clinico-investigative profile of 50 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2008;53:111–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.42387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Majumdar A, Singh TA. Comparison of clinical features and health manifestations in lean versus obese Indian women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2009;2:12–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-1208.51336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wijeyaratne CN, Balen AH, Barth JH, Belchetz PE. Clinical manifestations and insulin resistance (IR) in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) among South Asians and Caucasians: Is there a difference? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;57:343–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tayob Y, Robinson G, Adams J, Nyle M, Whitelaw N, Shaw R, et al. Ultrasound appearance of the ovaries during the pill free interval. Br J Fam Plann. 1990;16:94–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sundararaman PG, Shweta, Sridhar GR. Psychosocial aspects of women with polycystic ovary syndrome from south India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:945–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cresswell JL, Barker DJ, Osmond C, Egger P, Phillips DI, Fraser RB. Fetal growth, length of gestation, and polycystic ovaries in adult life. Lancet. 1997;350:1131–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)06062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dramusic V, Rajan U, Chan P, Ratnam SS, Wong YC. Adolescent polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;816:194–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bunker CB, Newton JA, Kilborn J, Patel A, Conway GS, Jacobs HS, et al. Most women with acne have polycystic ovaries. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:675–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb08208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunker CB, Newton JA, Conway GS, Jacobs HS, Greaves MW, Dowd PM. The hormonal profile of women with acne and polycystic ovaries. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:420–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1991.tb01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]