Abstract

We report an unusual and dramatic presentation of a rare form of cutaneous lymphoma, known as subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). This patient presented with a pruritic, florid and purpuric rash that was diagnosed as lobular panniculitis and treated with oral steroids for 1 year with no success. His skin lesions would return each time oral corticosteroids were being weaned off. Upon presentation to our clinic, repeated deep skin biopsies with immunohistochemical analysis coupled with the clinical history of persistent B symptoms and the presence of pancytopenia helped clinched the rare diagnosis of SPTCL with hemophagocytosis. The patient was then started on cyclosporine and dexamethasone before definitive chemotherapy. This rare and diagnostically challenging condition is commonly misdiagnosed as benign panniculitis or eczema, and highlights the importance of repeated skin biopsies.

Keywords: Lymphoma, panniculitis, purpura, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

What was known?

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) is rare and is diagnostically challenging.

Introduction

We report an unusual presentation of a rare form of skin lymphoma, subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL), that was first described in 1991,[1] and that accounts for less than 1% of all cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma,[2] representing a diagnostic challenge. The incidence of SPTCL in Europe is almost zero, whereas in Asian nations, its incidence reaches 2.3% to 3%.[3,4,5] Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL) typically presents as multiple, painless, subcutaneous nodules that resolve and then reappear in varying skin locations. As such, it is commonly misdiagnosed as benign panniculitis, dermatitis, eczema and psoriasis[6] resulting in delay of appropriate treatment and poor outcomes. In this unique case, the condition manifested as a dramatic and florid purpuric dermatosis with large spreading rings on the patient's trunk.

Case Report

A 25-year-old Chinese man presented with a 1-year history of a recurrent, pruritic, target-like and palpable rash. This was also associated with an intermittent fever over a 3-month period, which would result in occasional night sweats. There was no loss of weight or appetite. Histology of a skin biopsy done in another laboratory was reported as a lobular panniculitis. No immunohistochemistry was performed. The lesions would improve with courses of oral corticosteroid but reappeared when the medication was being tapered off. He subsequently sought a second opinion with our hospital.

On examination, widespread infiltrated purpuric plaques were seen over his trunk [Figure 1a]. On his back, there were large annular rings, some with central necrotic crusts [Figure 1b]. Petechiae were present in areas where pressure had been applied [Figure 1c]. There was no significant peripheral lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

Figure 1.

(a) Multiple purplish plaques over the trunk with petechiae. (b) Florid, purplish annular plaques over the back. (c) Petechiae and superficial necrosis over the pressure areas (where the blood pressure cuff lay)

Blood investigations revealed pancytopenia (leukocyte count 3.9 × 10^9/L, hemoglobin of 8.9 g/dL, platelet count 3000/uL). Inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) were not elevated. Autoimmune workup with anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), complement studies and anti-extractable nuclear antigens were unremarkable. Infective screens for dengue and retroviral disease were also negative.

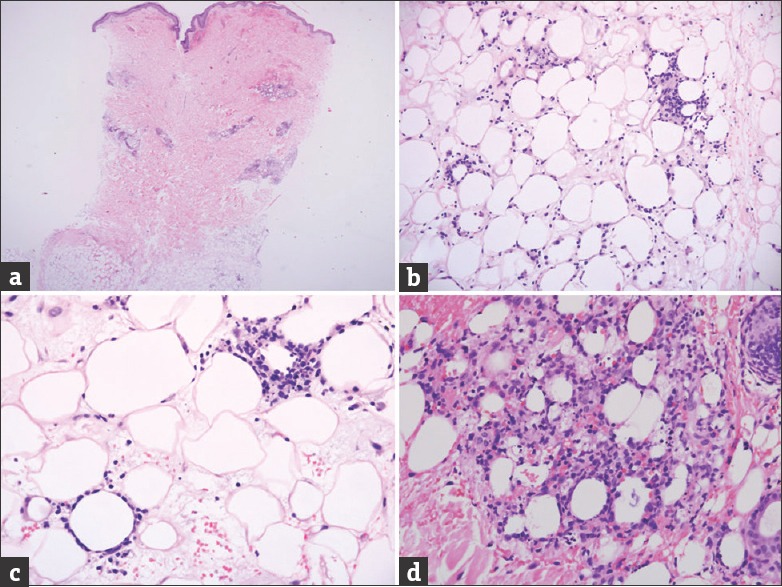

An initial biopsy performed in our center had only a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate and did not sample sufficient subcutaneous fat to assess for a possible panniculitic process. A deeper skin biopsy revealed atypical cytotoxic T-cell infiltrates in the dermis and in a panniculitic pattern, consistent with SPTCL [Figures 2 and 3]. The lymphocytes showed small to medium-sized nuclei and were seen to rim around the adipocytes.

Figure 2.

(a) Low power view of the skin biopsy shows perivascular and subcutaneous fat cellular infiltrate. (b) Medium power view of the subcutaneous fat shows a lobular lymphocytic infiltrate. (c) High power view shows that the lesional lymphocytes rim the adipocytes. Some nuclear dust is noted. (d) Another high power view shows marked lesional lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltrate amongst the adipocytes with nuclear dust. (Hematoxylin and Eosin, original magnification, A: ×20, B: ×100 and C and D: ×200)

Figure 3.

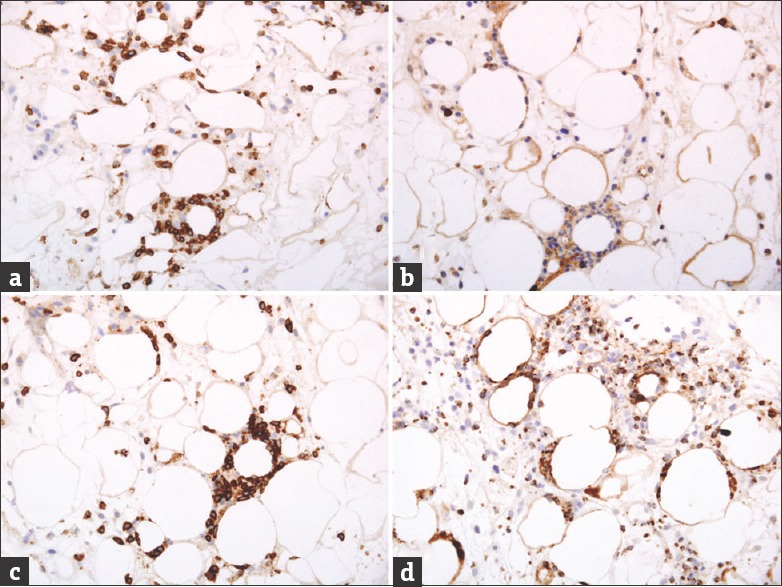

(a) Lesional lymphocytes with positivity for CD3. (b) Most lesional lymphocytes with negativity for CD4. (c) Lesional lymphocytes with positivity for CD8. Note the prominent rimming of the adipocytes by the lymphocytes. (d) Positivity for Granzyme-B. (Immunoperoxidase, original magnification: All ×200).

On immunohistochemical analysis, the lesional lymphocytes were reactive for CD3, CD8, Granzyme-B and Beta-F1. They were negative for TIA-1, CD4, CD56, CD20 and EBER (EBV encoded RNA)-in situ hybridization. The histiocytes were reactive for CD68 but not for myeloperoxidase.

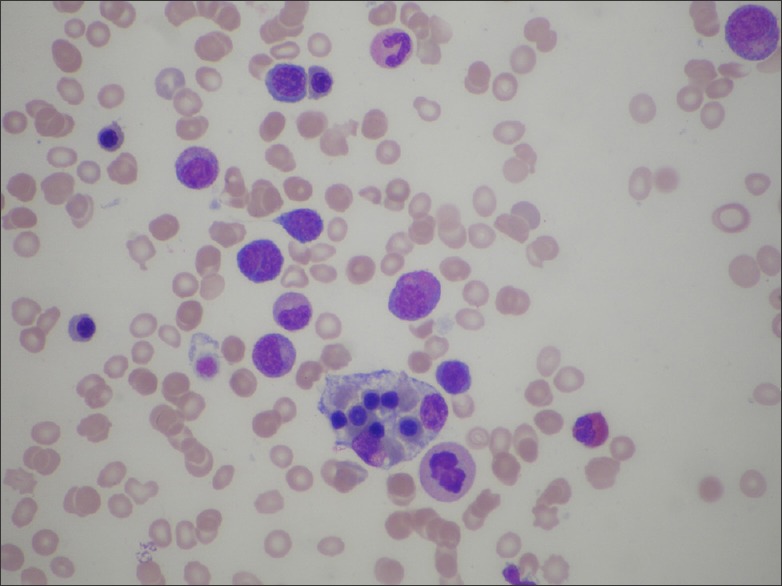

Bone marrow studies showed marked hemophagocytosis [Figure 4]. A full body positron emission tomography (PET) and computer tomography scan revealed only minimal subcentimeter nodes in the cervical, axillary, retroperitoneal, mesenteric and inguinal regions, which are non-specific. There was no bulky lymph node involvement.

Figure 4.

Bone marrow examination revealing the presence of hemophagocytosis

The patient was started on oral dexamethasone and cyclosporine for suppression of hemophagocytosis before choosing to return to his home country for definitive chemotherapy. Oral trimethoprim-sulfamethaxazole and acyclovir prophylaxis were also commenced.

Discussion

The diagnosis of SPTCL is based on pathological examination of skin and subcutaneous tissue biopsy, immunohistochemical staining patterns, molecular analysis, and clinical characteristics. More often than not, repeated biopsies are required before the diagnosis is made.

Patients with SPTCL tend to present with nodules or plaques, sometimes complicated with ulceration. Fever, weight loss and night sweats, or B symptoms, together with bone marrow suppression, are common. This is usually associated with multifocal skin lesions that typically develop on the arms, legs, and/or trunk.[7] The other cutaneous lymphomas such as mycosis fungoides, lymphomatoid papulosis, and anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma tend to affect mainly middle-aged men and normally do not warrant urgent aggressive treatment.[8] In contrast, SPTCL affects a broader age group including children and young adults, with varying outcomes. Survival has sometimes been reported as less than 3 years.[1]

With respect to its dermatological features, SPTCL tends to present as erythematous papulonodular lesions with subcutaneous infiltrates, classically with absence of lymph nodal involvement.[9] As it generally involves the subcutaneous fat, the clinical and pathological features mimic lobular panniculitis, especially lupus panniculitis. It is also important to note that more aggressive forms of cutaneous lymhoma may also infiltrate the dermis and epidermis and thus masquerade as dermatitis, eczema or psoriasis, leading to diagnostic confusion.

Histologically, the lymphoid infiltrates in SPTCL involve the fat lobules in a panniculitis-like pattern. Atypical lymphoid infiltrates are usually composed of small to medium cells with pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei. They surround the adipocytes, resulting in a classical rimmed appearance. While lymphocytic apoptotic bodies and even necrosis are sometimes seen, angiocentricity and angiodestructive patterns are not typical.[10]

Based on histology and immunohistochemical studies, SPTCL with αβ T-cell receptor (SPTCL- αβ) expresses the CD8+, CD3+, CD4- phenotype and is relatively indolent. This lymphoma is not commonly associated with hemophagocytosis (only up to 17%). Cutaneous lymphoma with γd T-cell receptor expresses CD3+, is usually CD4- and CD8-, and is typically associated with rapid clinical deterioration. Up to 50% of cases are associated with a co-existing hemophagocytosis syndrome (HPS). In addition, it should also be noted that for SPTCL, important clinical differences have been noted depending on the presence of HPS. Those with HPS tend to be refractory to CHOP-like chemotherapy and may require intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. Hence, early diagnosis of this disease entity and its appropriate classification is crucial in terms of treatment options and prognosis.[7]

PET scanning is useful for staging SPTCL and also for monitoring treatment responses whilst a patient is undergoing chemotherapy. Whole body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also appropriate for assessing the extent of disease and examining response to treatment.[11]

Regarding the treatment of SPTCL, systemic corticosteroids achieve only short periods of remission. Most commonly utilized initial chemotherapy usually involve CHOP (Cyclophosphamide, Hydroxydaunorubicin, Oncovin, Prednisolone)-like agents. Fludarabine-based intensive chemotherapy has also been used with remission rates of more than 70%. Other therapeutic options include the radiotherapy to localized skin lesions, autologous bone marrow and stem cell transplants.[11]

Although this patient's disease was classified as SPTCL, the presence of hemophagocytosis spells a significantly poorer prognosis and implies that CHOP-like chemotherapeutic regimes may not be sufficient to achieve remission. He would likely require high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation.[7]

Learning points

This case illustrates the importance of repeat biopsies in cases of high suspicion for rare diseases such as SPTCL, when initial biopsies are non-diagnostic. Red flags that should pique suspicion would include an unusual morphology, the presence of B symptoms and cytopenia(s)

When the index of suspicion is high, immunohistochemical studies must be considered. In this patient, his diagnosis was delayed by one year as a result of a previous skin biopsy reported as purely lobular panniculitis.

What is new?

We hope to highlight the importance of repeat biopsies in unusual cases of high suspicion of rare diseases such as SPTCL when initial biopsies are non-diagnostic, and to emphasize the importance of immunohistochemical analysis

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the assistance provided to us by Dr. Tung Moon Ley and the Hematology Department of the National University Hospital of Singapore for the bone marrow examination of this patient, and for proving the image [Figure 4] demonstrating hemophagocytosis.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Gonzalez CL, Medeiros LJ, Braziel RM, Jaffe ES. T-cell lymphoma involving subcutaneous tissue. A clinicopathologic entity commonly associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:17–27. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199101000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW, editors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues; p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenni D, Karpova MB, Seifert B. Primary cutaneous lymphoma: two-decade comparison in a population of 263 cases from a Swiss tertiary referral centre. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1071–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fujita A, Hamada T, Iwatsuki K. Retrospective analysis of 133 patients with cutaneous lymphomas from a single Japanese medical center between 1995 and 2008. J Dermatol. 2011;38:524–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao JB, Chuang SS, Chen HC, Tseng HH, Wang JS, Hsieh PP. Clinicopathologic analysis of cutaneous lymphoma in taiwan: a high frequency of extranodal natural killer/t-cell lymphoma, nasal type, with an extremely poor prognosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:996–1002. doi: 10.5858/2009-0132-OA.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagheri F, Cervellione KL, Delgado B, Abrante L, Cervantes J, Patel J, et al. An illustrative case of subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma. J Skin Cancer 2011. 2011:824528. doi: 10.1155/2011/824528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willemze R, Jansen PM, Cerroni L, Berti E, Santucci M, Assaf C, et al. EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Definition, classification, and prognostic factors: An EORTC Cutaneous Lymphoma Group Study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008;111:838–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulli M, Berti E. Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (including rare subtypes). Current concepts. II. Haematologica. 2004;89:1372–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sy AN, Lam TP, Khoo US. Subcutaneous panniculitislike T-cell lymphoma appearing as a breast mass: A difficult and challenging case appearing at an unusual site. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:1453–60. doi: 10.7863/jum.2005.24.10.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salhany KE, Macon WR, Choi JK, Elenitsas R, Lessin SR, Felgar RE, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: Clinicopathologic, immunophenotypic, and genotypic analysis of alpha/beta and gamma/delta subtypes. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;22:881–93. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Go RS, Wester SM. Immunophenotypic and molecular features, clinical outcomes, treatments, and prognostic factors associated with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: A systematic analysis of 156 patients reported in the literature. Cancer. 2004;101:1404–13. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]