Abstract

Ultrasound increases efficacy of drugs delivered from micelles, but the pharmacokinetics have not been studied previously. In this study, ultrasound was used to deliver doxorubicin sequestered in micelles in an in vivo rat model with bilateral leg tumors. One of two frequencies with identical mechanical index and intensity was delivered for 15 minutes to one tumor immediately after systemic injection of micellar doxorubicin. Pharmacokinetics in myocardium, liver, skeletal muscle, and tumors were measured for one week. When applied in combination with micellar doxorubicin, the ultrasoincated tumor had higher doxorubicin concentrations at 30 minutes, compared to bilateral noninsonated controls. Initially, concentrations were highest in heart and liver, but within 24 hours they decreased significantly. From 24 hours to 7 days, concentrations remained highest in tumors, regardless of whether they received ultrasound or not. Comparison of insonated and noninsonated tumors showed 50% more doxorubicin in the insonated tumor at 30 minutes post-treatment. Four weekly treatment produced additional doxorubicin accumulation in the myocardium but not in liver, skeletal leg muscle, or tumors compared to single treatment. Controls showed that neither ultrasound nor the empty carrier impacted tumor growth. This study shows that US causes more release of drug at the targeted tumor.

Keywords: ultrasound, drug delivery, doxorubicin, rat tumor model, pharmacokinetics

Introduction

In the effort to locally treat neoplasms, many novel techniques are being developed. One such method involves loading chemotherapeutic drugs inside stabilized micelles and injecting the encapsulated drug into the circulatory system. Ultrasound (US) is then focused on a tumor in an effort to locally deliver the drug at the diseased site only. This treatment ideally has the potential to not only spare the rest of the body from the toxic side effects of the drug, but also to locally increase the drug concentration in the cancerous tissue, thus increasing the drug’s effectiveness. Our research employs ultrasonic delivery of the common chemotherapeutic drug doxorubicin (Dox) in a rat model.

Ultrasound is a convenient tool in drug delivery because it can be non-invasively focused on the cancerous tissues. The frequency and intensity of US is manipulated to produce cavitation events within the tissue, defined as the generation and oscillation of gas bubbles. 1–3 The rapid oscillation and violent collapse (called collapse or inertial cavitation) of bubbles releases drug from the carrier that we have developed. 4,5 Collapse cavitation is also stressful to cells because the high shear stresses and shock waves can transiently or permanently create micropores in cell membranes. 6–12 In general, the likelihood and intensity of collapse cavitation is indicated by the “mechanical index” (MI), the ratio of peak negative pressure, P−, (in MPa) to the square root of frequency, f, (in MHz). 13 The threshold for the initiation of collapse cavitation occurs at a MI of approximately 0.3, whereas drug release from our carrier occurs at MI ≥ 0.38. 4,14

As mentioned, US at low frequencies has been shown to trigger the release in vitro of the hydrophobic Dox from Pluronic™ micelles. 4,5,14–18 Nelson et al. developed an in vivo rat model to investigate the effects of ultrasonically controlled release of micelle-encapsulated doxorubicin. 19,20 The particular micellar carrier used in their work is called NanoDeliv®, and consists of polyether triblock surfactant stabilized by an interpenetrating network of a thermally sensitive polyacrylamide. 21 During the course of their four-week treatment, tumors in this experiment were exposed to 20- or 70-kHz ultrasound for one hour following each weekly dose of Dox encapsulated in NanoDeliv®. Those results showed that application of low-frequency ultrasound and encapsulated Dox injections (via intravenous administration) at concentrations of 2.67 mg/kg resulted in a significant decrease in tumor size compared to non-insonated controls. 19 A more recent study showed that 15 min of treatment at 20 kHz or 476 kHz was also effective. 22 The present study goes beyond these previous studies to address some significant unresolved issues concerning possible mechanisms. Foremost is the test of the hypothesis that US causes drug release from NanoDeliv® in vivo. Another unresolved postulate is whether lower frequency US was more effective than higher frequency US in drug release. The present study held the mechanical index and time-averaged power intensity constant in order to look solely at the effect of frequency in an attempt to examine how frequency influences the distribution of Dox in various tissues, as well as it influence upon the final therapeutic effect of inhibiting tumor growth.

Dox Pharmacokinetics

While doxorubicin is successful in fighting certain types of cancer, it can cause side effects, the most severe being cumulative dose-dependent cardiotoxicity, often leading to cardiomyopathy with subsequent congestive heart failure. The incidence of Dox-induced cardiotoxicity becomes critical when the total cumulative dose administered approaches 450 to 500 mg/m2. 23 The therapeutic dose in adults is 20–75 mg/m2 as a single intravenous injection every three weeks.

For the past three decades, researchers have studied the pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin in various applications. A few of these applications include administration of free Dox (dissolved in saline) 23–25, or loading the drug into carriers such as liposomes 23,24 or micelles. 26 Free Dox displays a biphasic deposition in plasma after intravenous injection in rats and humans. For example in humans, free Dox has a distributive half-life of about 5 minutes and a terminal half-life of 20 to 48 hours,27 showing fast drug uptake into the tissues but slow elimination thereafter.

Tavoloni and Anthony analyzed Dox excretions in rat bile and urine and found that the data fit a two-compartment pharmacokinetic model. 25 Both biliary and urinary excretion followed the biphasic pattern. For example, after injection the labeled drug appeared in the bile within 3–5 minutes and reached peak excretion and concentration levels after 30 minutes, with the peak concentration strictly proportional to the administered dose. After reaching the maximum systemic concentration, the excretion of the drug declined with time in a monophasic pattern. 25

Alakhov et al. studied the pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of Dox formulated with SP1049C, a modified Pluronic™ compound, in normal and tumor-bearing mice. 28 Comparing the Dox/SP1049C formulation to free Dox, they reported that the block copolymers produced little effect on the pharmacokinetic profiles of the drug in liver, kidney, heart, or lung in either normal or tumor-bearing mice. However, comparison of data from micellar and free drug formulations revealed a statistically substantial 1.7-fold increase in drug accumulation in the solid tumors when micelles were used. 28 Pharmacokinetic studies on Pluronic™ compounds showed that these block copolymers are eliminated primarily by renal excretion. 26 Also, Pluronic™ concentrations in the plasma remain quite high for several hours after administration. 29

This report presents the concentrations of Dox in different tissues at various times post-insonation, from thirty minutes to one week. Furthermore, the effect of ultrasonic parameters, such as frequency and intensity, upon drug distribution is reported.

Materials and Methods

Drug/NanoDeliv® Preparation

The drug carriers used herein were stabilized Pluronic™ P105 micelles that were synthesized as described previously and stored at −20°C until use. 21 These micelles, called NanoDeliv®, contain a hydrophobic core of polypropylene oxide and an outer corona of polyethylene oxide, stabilized using an interpenetrating network of thermally responsive N,N-diethylacrylamide. Their average diameter of 50 to 80 nm allowed them to be sterilized by filtration. Dox was loaded into these micelles by introducing 3.75 ml of carrier suspension into a 10 mg vial of Dox via a 0.22-μm membrane filter. After thorough mixing, the Dox/micelle formulation was stored at −20°C and only thawed for short periods prior to injection.

Rat and Tumor Type

All procedures involving rats followed NIH guidelines for humane animal use and care, and were approved by IACUC of Brigham Young University (protocol number 080601). The BDIX rat readily grows the DHD/K12/TRb colorectal epithelial cancer cell line, which is susceptible to doxorubicin. 30 Studies show that this cell line can be injected anywhere in the BDIX rat to successfully produce tumors.31 Cells were inoculated by the injection of 25 μL of 2 × 106 cell/mL suspension intradermally over the lateral aspect of each posterior leg. After 3 weeks, measurable tumors had formed.22

Ultrasound Instrumentation

Rat tumors were insonated via either a 20-kHz ultrasonic probe (Vibra-Cell 400 VCX; Sonics & Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT) or a 476-kHz ultrasonic transducer (Sonic Concepts, Woodinville, WA). The 20-kHz probe operated in a continuous wave mode with an intensity of 1.0 W/cm2 at the tip (pressure amplitude of 0.173 MPa). The mechanical index at these conditions is 1.22. In order to match that mechanical index at the 476-kHz frequency, a pulse intensity of 23.61 W/cm2 (pressure amplitude of 0.842 MPa) was required. However, transmitting this amount of energy would most likely cause thermal damage to the rat. Therefore, the 476-kHz transducer was operated with 1,000 cycle pulses at a pulse repetition frequency of 20.161 Hz (duty cycle of 1/23.61) to create a temporal average intensity of 1.0 W/cm2. Thus both ultrasonic applications had the same mechanical index of 1.22 and the same temporal average power density of 1.0 W/cm2.

Experimental Design

Fifty-five rats were divided into three groups – Group A, Group B, and Group C – according to the time after Dox-injection at which they were euthanized and the types of tissues collected for analysis of Dox distribution. Group A consisted of sixteen rats that were euthanized at either 0.5, 3, 6, or 12 hours after insonation (four rats per time point), and both the insonated and non-insonated tumors were removed. Of these, half were insonated at 20 kHz and half were insonated at 476 kHz. The twelve rats enrolled in Group B had none or only 1 tumor and were euthanized at either 1, 6, 12, 24, or 48 hours after insonation (two to three rats per time point); the heart, liver, leg muscle, and tumor (if any) were removed. The remaining 15 rats in Group C were euthanized at either 0.5, 8, 12, 48, 96, or 168 hours after insonation (two to three rats per time point); only the heart and tumors were removed for analysis.

A control study without any drug was performed to determine any effect of US alone (no drug or carrier) or of the empty micellar carrier (no drug). Twenty-eight rats having tumors on both legs were divided into 4 treatment groups: 1) no US and no NanoDeliv®, 2) no US with NanoDeliv®, 3) 20 kHz US and no NanoDeliv®, and 4) both 20 kHz US and NanoDeliv®. There were 6 to 8 rats in each group, and each rat was injected with either NanoDeliv® or saline. Sham ultrasound was applied (transducer not activated) to the tumor when the treatment indicated “no US”. As with the experimental group, the treatments were applied once a week for 6 weeks, and the tumor volumes and rat weights were recorded at least weekly for at least 6 weeks, and up to the time of death or euthanization at 12 weeks.

Doxorubicin Injection and Ultrasound Application

Administration of the encapsulated Dox (2.67 mg-drug/kg-rat) was given via infusion set in the lateral tail vein. The appropriate volume of encapsulated Dox was drawn into a 1 ml syringe and then administered through the septum of a 12-cm microbore extension (LifeSheild, Hospira Inc., Lake Forest, IL) connected to a 27-ga. butterfly catheter (Surflo, Terumo Medical, Somerset, NJ). This was chased by 3 ml of the saline to completely flush the drug from the catheter. Only one tumor on the animal was exposed to ultrasound (the other serving as non-insonated control), and the same tumor was exposed each week, commencing within five minutes of the Dox injection. Ultrasound was applied for fifteen minutes.

Doxorubicin Extraction and HPLC Analysis

After euthanasia by CO2 asphyxiation, the desired tissues were immediately removed, placed in vials, and frozen in crushed dry ice. Dox in the tissues was extracted by a modification of the method described by Álvarez-Cedrón et al. 32 The entire tissue (heart, tumor, etc.) was weighed and then homogenized with 0.067 M potassium phosphate solution using an Ultra-Turrax® T 25 basic dispersion tool (IKA Works, Inc; Wilmington, NC). Enough potassium phosphate solution was added to create the following tissue-dependent concentrations upon homogenization: 50 mg liver/ml solution, 25 mg heart/ml solution, 15 mg muscle/ml solution, and 15 mg tumor/ml solution.

For every collected tissue, duplicate extractions and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses were performed. First, 0.15 ml of tissue homogenate was mixed into a 3 ml microfuge vial containing 0.20 ml of extraction solution, which was an equal volume combination of methanol and of 40% ZnSO4 aqueous solution. The mixture was vortex mixed for 30 seconds, after which it was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, 50 μl of the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system. The mobile phase was a mixture of 65 vol% methanol and 0.01 M phosphate buffer flowing at 1.2 ml/min. The HPLC system also used a Waters Novapak C18 column, a Waters fluorescence detector (λexcitation = 480nm, λemission = 550 nm), and Millennium data analysis software (Waters Corp., Milford, MA). The HPLC system quantified the amount of Dox in each injection, from which the drug concentration in the collected tissues was calculated. Calibration curves were made from Dox hydrochloride dissolved in the mobile phase buffer.

Results

Control Experiments without Dox

Control experiments investigated the effect of the US and the empty NanoDeliv® carrier in the absence of drug. Tumor volume growth curves for both treated and untreated legs were analyzed jointly using a longitudinal statistical model. The results indicate that neither the US treatment nor the use of the NanoDeliv® carrier, nor the combination thereof, had any statistically significant effect on the tumor size (p = 0.0741).33 If anything, rats in the group receiving both US and empty carrier had lower tumor growth rates. Neither did the use of US or NanoDeliv® have any negative effects on the survival of the rats. In fact the rats in the group receiving both US and empty carrier survived longer than those in the other 3 groups (p < 0.0001).33

Pharmacokinetics Experiments

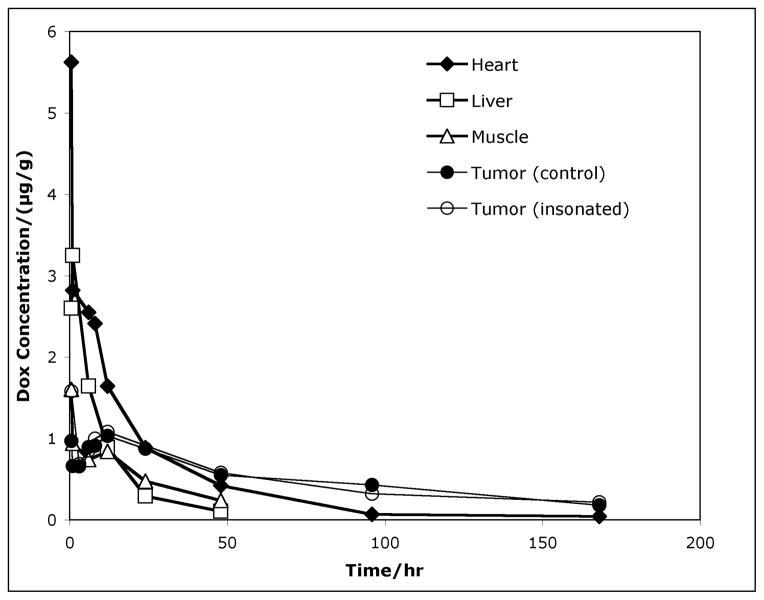

The data from the HPLC analysis is presented in Figure 1 and shows the average Dox concentration in the heart, liver, leg muscle, non-ultrasonicated tumor, and ultrasonicated tumor over the course of one week (168 hours) following drug administration. These data were collected from individual rats in various experiments over a two-year period. Each point represents anywhere between 1 to 20 measurements from 1 to 9 tissue samples. A total of 263 measurements were used to construct these plots. Data from both frequencies are combined in these plots because a statistical analysis showed that any differences due to frequency are not significant (see discussion).

Figure 1.

Average Dox concentration in the heart (◆), liver (□), leg muscle (△), non-ultrasonicated tumor (●), and ultrasonicated tumor (⭕) of the rats as a function of time following drug administration.

Drug concentrations at short times after ultrasound application were of particular interest, as were the drug concentrations in the treated and untreated tumors. The Dox concentration in the heart was very high at short times (30 min) post-treatment, but it decreased six-fold within 24 hours, and within 2-days post-treatment it reached concentrations lower than in the tumors. Similarly, the liver initially contained elevated Dox concentrations, but within 24 hours decreased to less than one-tenth of the initial levels. The leg muscle (adjacent to the tumors) initially contained Dox concentrations comparable to those in the tumors, but after about 12 hours, the levels in the leg musculature decreased more than in the tumors. The Dox concentrations in both non-insonated and insonated tumors initially were significantly less than in the more vascularized tissues (i.e. heart, liver); the concentration increased from zero to a maximum of 0.9 and 1.6 μg/g respectively at 30 minutes; the concentration then decreased to a minimum of 0.7 μg/g at 3 hrs, and then increased to another maximum of 1.1 μg/g at 12 hr. Finally the concentration decreased at a slower rate than the other tissues, resulting in comparatively higher average drug concentrations in the tumors after as little as 24 hours. Most importantly, the Dox concentration in the insonated tumors was greater than the non-insonated control only at the 30-minute time point; at later times the concentrations in the control and insonated tumors were not statistically different.

Using the drug concentrations in each tissue, the total weight of each organ or tumor, and the total amount of Dox injected into each rat, the percent of the total amount of Dox injection found in each organ or tumor was calculated. Because rat livers are much larger than their hearts, about 5% of the amount of Dox injected in the rat was found in the liver during the first hour after treatment whereas only about 0.5% was in the heart during the same time. Table 1 lists the average percentage of the injected Dox in the liver, heart, and tumors (both insonated and non-insonated) at various times after treatment.

Table 1.

Percent of Injected Doxorubicin Dose Found in Various Tissues at Various Times After Treatment

| Tissue | 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 168 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 4.871% | 5.432% | 2.744% | 1.476% | 0.484% | 0.172% | ||||

| Heart | 0.668% | 0.379% | 0.297% | 0.261% | 0.206% | 0.126% | 0.056% | 0.011% | 0.007% | |

| Tumor | 0.086% | 0.077% | 0.060% | 0.050% | 0.108% | 0.009% | 0.024% | 0.006% | ||

| Tumor (US) | 0.057% | 0.117% | 0.050% | 0.063% | 0.106% | 0.011% | 0.009% | 0.026% | 0.007% |

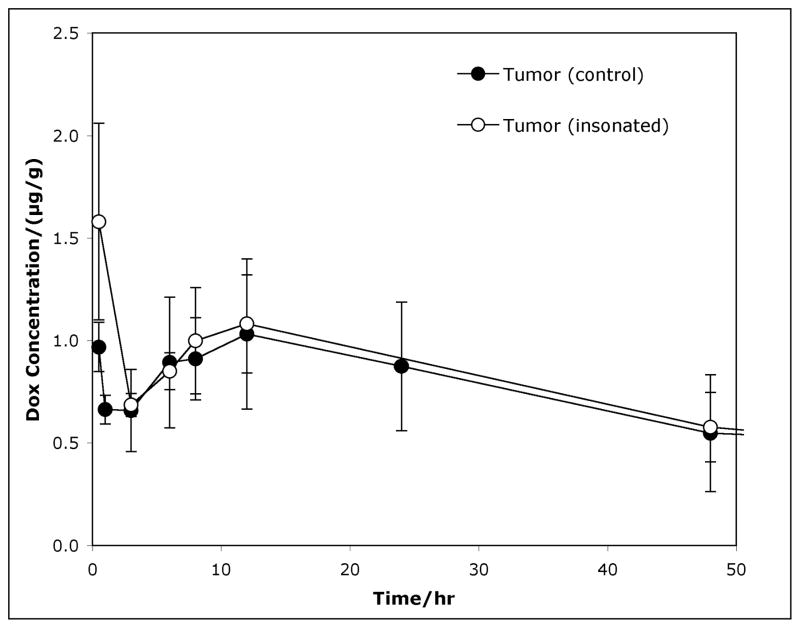

Drug Concentrations in Treated (Ultrasonicated) versus Non-Insonated (Control) Tumors

Figure 2 shows expanded detail of the average drug concentration (μg Dox per gram of tumor) for Dox in rat tumors (insonated and non-insonated) over the course of two days post-treatment. Comparison (see Table 2) between insonated tumors and control tumors (no US) showed no statistical difference in Dox concentrations beyond 30 minutes (i.e. 3 hours, 6 hours). At 30 minutes post-treatment, the mean Dox concentration was 1.47 μg/g and 0.94 μg/g for insonated and control tumors, respectively. This is marginally statistically significant (p = 0.055). Thus, the data may suggest that the application of ultrasound to the tumor increases the average Dox concentration to about 50% greater than in the contralateral tumor at the 30-minute time point. However by 3 hours and beyond, there was no statistical difference between the Dox concentrations in the two groups of tumors.

Figure 2.

Average drug concentration (μg/gram-tumor) of Dox in rat tumors over the course of two days after ultrasound treatment. The graph compares tumors which received ultrasound (US) (●) and those that did not (■). The bars represent the 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Statistical Summary: Dox Concentrations in Insonated Tumors (US) Versus Noninsonated Tumors (No-US)

| Time after treatment (h) | 0.5 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 12 | 24 | 48 | 96 | 168 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean DOX conc. (μg-DOX/g-tumor) (US) | 1.47 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 1 | 1.14 | 0.874 | 0.532 | 0.32 | 0.22 |

| Mean DOX conc. (μg-DOX/g-tumor) (no-US) | 0.94 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.652 | 1.09 | — | 0.604 | 0.43 | 0.18 |

| Standard Deviation (μg-DOX/g-tumor) (US) | 1.018 | 0.056 | 0.258 | 0.672 | 0.574 | 0.315 | 0.188 | 0.164 | 0.282 |

| Standard Deviation (μg-DOX/g-tumor) (no-US) | 0.287 | 0.13 | 0.402 | 0.657 | 0.384 | — | 0.343 | 0.302 | 0.092 |

| Sample size-n (US) | 14 | 6 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| Sample size-n (no-US) | 11 | 8 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| p-value (one-tail) | 0.055 | 0.326 | 0.317 | 0.105 | 0.395 | N/A | 0.34 | 0.246 | 0.399 |

| 95% conf. interval (US) | 0.99–1.95 | 0.64–0.73 | 0.8–1.03 | 0.7–1.29 | 0.9–1.37 | 0.45–1.3 | 0.42–0.65 | 0.17–0.47 | 0.0–0.52 |

| 95% conf. interval (no-US) | 0.78–1.09 | 0.57–0.74 | 0.72–1.25 | 0.28–1.03 | 0.92–1.26 | — | 0.3–0.91 | 0.19–0.67 | 0.08–0.27 |

Ultrasound Frequency Effect on Drug Concentration

The data in Fig 2 includes rats having tumors on only one leg and those with tumors on both legs. Those with bilateral tumors were treated repeatedly for 6 weeks (the short-term experiment group) with 20- or 476-kHz insonation. These 16 rats were euthanized at 0.5, 3, 6, or 12 hours after receiving their last ultrasound treatment on the sixth week, with four rats at each time point – two of which received 20-kHz insonation and two of which received 476-kHz insonation. Each drug concentration measurement was performed twice for each of the two tumors (insonated and non-insonated tumors). Because these rats had tumors on both legs, a paired-sample comparison of insonated and non-insonated control tumors on the same rat was evaluated using a student t-test. These results showed no statistical difference between the drug concentrations in the insonated tumors and control tumors (p = 0.988), regardless of the frequency employed. Comparison of Dox in the tumors in the group that received 20-kHz US to that in tumors receiving 476-kHz insonation showed no difference in drug concentration within the ultrasonicated group (p = 0.957), or within the non-ultrasonicated group (p = 0.934). It is noteworthy that measurement of tumor volume in these same rats showed no difference in tumor growth rate when these two different frequencies were applied with the same MI and time-averaged intensity. 22 In other words, the frequency employed had no statistical effect on drug concentration in the tumors.

Long Term Drug Accumulation Experiment

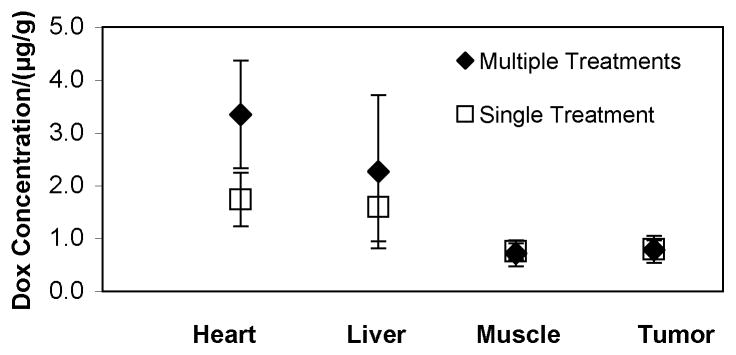

Three rats were given the Dox/NanoDeliv®/US treatment for four consecutive weeks before being euthanized six hours after the last treatment in order to examine whether repeated treatments produced any type of successively increasing drug accumulation in any tissues. The Dox concentrations in the heart, liver, leg muscle, and tumor (which were exposed to only 20-kHz insonation) were compared between rats that had received four consecutive weeks of drug injection and ultrasound treatment and rats that received only a single treatment. The results of this study are displayed in Figure 3, which compares the averages of the measurements. Statistical analysis showed a greater amount of Dox in the heart tissue at the end of four weekly treatments compared to a single treatment (p = 0.044), but there were no statistically significant differences in concentrations between the single and multiple treatment groups in the liver, leg muscle, and tumor tissues (p = 0.262, p = 0.397, and p = 0.327, respectively).

Figure 3.

Mean and 95% CI of Dox concentration in different rat tissues (heart, liver, leg muscle, and tumor). Two rats were euthanized after four consecutive weeks of treatment (

) and two rats were euthanized after only one treatment (

) and two rats were euthanized after only one treatment (

). All four were euthanized six hours after ultrasound treatment (20 kHz for fifteen minutes).

). All four were euthanized six hours after ultrasound treatment (20 kHz for fifteen minutes).

Discussion

A new cancer treatment method was evaluated in vivo using the BDIX rat model of a colon carcinoma. This treatment involved the localized delivery of Dox using stabilized micelles (NanoDeliv®) as the drug carrier and low frequency ultrasound as the mechanism to release the drug into the tumor. As part of this research, the kinetics of Dox distribution in various tissues and the effects of 2 different ultrasonic frequencies on drug delivery were successfully studied.

The control experiments without drug (empty carrier and/or ultrasound) show that the application of US at these low intensities has no adverse effect on the growth of the tumor or on the survival of the rats.33 Although all of the control rats eventually died of metastatic disease, insonation of the tumor did not measurably accelerate the growth of the tumor or the course of the metastatic disease. Furthermore, the empty carrier by itself appears to have no toxic effects measurable by weight loss or lifespan.

When Dox was administered via NanoDeliv®, the drug distribution in the heart, liver and skeletal muscle showed an exponential-type decay with time, suggesting that there might be a dynamic equilibrium between the blood and tissue compartments in these organs, and that the Dox concentration decreases monotonically as it is cleared from the body. The pharmacokinetic data in the tumor, however, were very different. Both non-insonated and insonated tumors showed an increase in concentration to a maximum at 30 minutes, followed by a decrease and then another increase to a maximum at 12 hours. The final decay in concentration beyond 12 hours was much slower than the clearance from the heart, liver and muscle, suggesting that it was not in dynamic equilibrium with Dox in the blood.

In contrast to normal tissue, many types of tumors contain a high density of abnormal blood vessels that have higher vascular permeability.34 Higher permeability has been attributed to larger interendothelial cell gaps, and increased capillary fenestration.35 Poor drainage by the lymphatic system also contributes to the buildup of macromolecules and nanoparticles in these types of tumors. For example, many tumors passively collect drug-containing liposomes having diameters from 90 to 300 nm, and accumulate labeled dextrans and other macromolecules of the same or slightly smaller size scale.34,35 This is commonly called the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect. Measurable accumulation is evident 30 minutes post-administration, and may continue for hours.

In our study, the maximum in drug accumulation in the tumors at 12 hours strongly suggests that there is an EPR effect occurring in these tumors with these drug-containing micelles. This maximum does not correlate with the monotonically decreasing concentrations in the heart, liver and adjacent skeletal muscle tissue, and suggests that some kind of compartmentalization is occurring. The persistence of the drug in the tumor for much longer times than the other tissues is also indicative of an EPR effect. Although the presence or absence of an EPR effect has not been reported previously for this DKD/K12 tumor, we propose that the maximum in drug concentration in the tumor at 12 hours is strongly indicative of an EPR effect in this tumor model. If we accept this hypothesis, then it appears that US has little if any influence on the EPR effect, at least beyond 3 hours post-insonation, since both insonated and non-insonated control tumors have the same Dox concentration attributed to enhanced permeation and retention. Other authors have suggested that US increases capillary permeability for short times after insonation. 36–39 If that is the case in our tumor model, then the insonated capillaries appear to have recovered by 3 hours post-treatment.

The high Dox concentrations in both the insonated and non-insonated control tumors at 30 minutes is attributed to the high Dox concentration in the blood immediately following injections, which decays similarly to the concentrations in the heart, liver and muscle until its signal is smaller than that from the accumulation in the tumor due to the EPR effect. We postulate that at these relatively short times, there is not enough time for appreciable accumulation of Dox-carrying micelles in the tumor due to the EPR effect. The maximum in concentration in the non-insonated tumor at 30 minutes is attributed to dynamic equilibrium with higher free and encapsulated Dox concentrations in the blood compartment, just as is seen in the adjacent muscle tissue. But why is there much more Dox in the insonated tumor at these short times? We speculate that the higher concentration is caused by Dox being released from micelles by ultrasonic activity, and that the diffusion of released drug into the tissues creates higher Dox concentrations only transiently. This concentration is over and above the high concentration observed in the non-insonated control tumors. These and other possible scenarios will be discussed later in this section.

Parallel experiments under the same experimental conditions (reported elsewhere 22) showed that after injection of Dox encapsulated within NanoDeliv®, the insonated tumors grew slower, on average, than the non-insonated control tumors that received the same systemic exposure to the drug formulation (p < 0.001). Thus US produced some beneficial effect to slow the tumor growth rate. But what were the mechanisms? One proposed hypothesis, consistent with the release profile discussed in the preceding paragraph, is that the ultrasound caused drug release from the micelles, depositing more Dox in the ultrasonicated tumor tissue. Although such a hypothesis is consistent with many in vitro studies4,14–18,40,41, this paper reports the first evidence that this also occurs in vivo. Furthermore, if ultrasonic release is occurring in vivo, the short-lived spike in Dox concentration is sufficient to slow tumor growth rate.

Because Dox is cardiotoxic, it is noteworthy that a small amount of this drug remains in the heart tissue at 48 hrs. Repeated exposure appears to increase the amount of Dox remaining in the heart at 6 hrs (see Fig 3). Since there were no concurrent studies performed using non-encapsulated (or free) Dox, no conclusion can be made as to the effect of the NanoDeliv®, if any, in protecting the heart by decreasing the amount of drug in the heart.

The initial high concentration of Dox in the liver was not unexpected considering that doxorubicin is primarily cleared through the biliary route. After two days, the amount of Dox in the liver was negligible, indicating that the drug had left the circulatory system and had been cleared or had settled in its final locations, such as in the tumors.

It was encouraging to see that in the long term (> 2 days), there was a higher concentration of Dox in the tumors than in the liver, skeletal muscle, and the heart. Though there was no difference in drug concentration between insonated and non-insonated tumors after one day, a detectable amount of Dox persisted in the tumors even at 1 week. The present study could not distinguish whether this drug had been released from the micelles during ultrasonication. It is possible that sustained concentration of the drug in the tumors occurred because the micelles protected the drug from being metabolized or cleared by the liver or kidneys. It is also possible that the drug remained in the NanoDeliv® after the micelle had been transferred from the circulatory system to the tumor interstitium through the leaky tumor capillaries. However, it is also likely that after one week the stabilized micelle would have disassociated, thus releasing its drug load. Previous studies by Pruitt showed that the half-life of NanoDeliv® micelles is about 17 hrs, so we expect that the NanoDeliv® carriers were completely degraded within one week18,21 and that the Dox remaining in the tumor at seven days is no longer encapsulated in the micelles.

The observation that a tumor receiving US and Dox/NanoDeliv® had a slower average growth rate than the bilateral non-insonated tumor indicates that insonation does produce a difference related to the chemotherapeutic effects of Dox. We propose three possible mechanisms, all of which could be operable. The first mechanism is that US does indeed release Dox from NanoDeliv® in vivo as it does in vitro. Such ultrasonically activated release may account for the higher concentration of Dox extracted from insonated tumors than non-insonated tumors at the 30-minute time point. If Dox were released during the 15 minutes of insonation, then one would expect to see a higher concentration in the insonated tumor tissue shortly thereafter, but the released Dox would not necessarily remain in the region for longer times unless it was irreversibly absorbed by the tissues.

A second proposed mechanisms is that US permeabilizes the tumor cell membrane, enhancing the uptake of NanoDeliv® particles containing Dox, and/or free Dox that might be released from micelles by the ultrasound. As mentioned, Schlicher 9 and others 8,11,42,43 have shown that cavitation events produced by US create transient, repairable holes in cancer cell membranes, through which drug and perhaps small nanosized particles can pass into the cytosol.

The third mechanism is that US may be enhancing the permeability of the capillaries in the tumor, as Kruskal and others have reported. 36–39 Though reports are abundant, the mechanisms producing enhanced capillary permeability are not yet known.

Our observations reported herein and elsewhere have led us to formulate the following scenario of ultrasonically activated drug delivery in tumors with leaky capillaries. Upon injection, Dox-containing NanoDeliv® nanoparticles (50–200 nm in diameter) circulate throughout the animal, including the capillaries of the tumor. A small fraction of these nanoparticles continually extravasate into the tumor tissue where they collect, building up the concentration over the first 12 hours while the micelle concentration in the blood is high. NanoDeliv® micelles are eventually cleared from the circulatory system by extravasation into tumors and clearance via the liver. (They are too large to be cleared by glomerular filtration.) During insonation, from about 2 to 17 minutes post-injection, most NanoDeliv® micelles are still in the circulatory system, with relatively few extravasated NanoDeliv® carriers in the tumor at this time. Cavitation events may release Dox from both circulating and extravasated NanoDeliv® micelles in the tumor. The released Dox from circulating micelles could diffuse from the capillaries into the tissues, thus producing the higher concentration in the insonated tissue at 30 minutes. Insonation also might transiently increase the capillary permeability allowing even greater extravasation. With further passage of time, Dox-containing NanoDeliv® particles continue to extravasate, but at slower rates as NanoDeliv® is cleared from the circulatory system and the capillaries regain their normal permeability. Free Dox in the tumor tissue, such as Dox that was release by US but not taken up by cells or Dox that was exported from cells, is flushed away by the lymphatic drainage. Thus by 3 hrs post-exposure, there is little difference between Dox concentration within the insonated and non-insonated tumor tissue. Dox concentration continues to build in the tissues during the first 12 hours as normal levels of extravasation continue, but then eventually declines as the circulatory system is cleared of the NanoDeliv® and as the extravasated NanoDeliv® degrades and releases its payload of Dox. Apparently the short exposure to higher Dox concentrations around the 30-minute time point is sufficient to slow the growth rate of the insonated tumor.

This study found that the ultrasonic frequency has no measurable effect on Dox concentration in tumor tissues, which is consistent with our study showing the lack of any effect of US frequency on tumor growth rate.22 Yet to be tested is the effect of mechanical index and power density on drug concentration in the tumor, or on tumor growth rate. A larger mechanical index or power density could produce a stronger therapeutic effect, but that remains to be tested. Future studies should consider the effect of different mechanical indices and time-averaged power intensities on growth rate and drug concentrations in the tumor.

Conclusions

The combination of Dox encapsulated within NanoDeliv® micelles followed by exposure to low-frequency ultrasound (at an intensity large enough to promote inertial cavitation) increased the average drug concentration by about 50% in the tumor around the 30-minute time point post-treatment. However, this observation is tempered in that it is only marginally statistically significant (p=0.055). The data supports our hypothesis that US increases drug delivery to targeted tumors (p<0.001). However, the exact mechanisms producing increased concentration and decreased growth rate is still unknown. The ultrasound could have 1) released more drug from the micelle carriers; 2) increased the permeability of the cancer cell membranes, allowing the drug to achieve higher concentrations in the cytosol; and/or 3) increased the permeability of the capillaries (effectively increasing the EPR effect), allowing more NanoDeliv® and its drug to enter into adjacent tissue. Any single one, or combination, of these mechanisms could cause an increased amount of Dox in the tumor tissue. The effect of ultrasound on average drug concentration is, however, short lived. After twelve hours, there is no difference in Dox concentration between insonated and non-insonated tumors.

The insonation frequency had little effect on pharmacokinetics in that changing the frequency more than 10-fold (while keeping the same mechanical index and time-averaged power density) produced no measurable effect on Dox concentration in the tumors and no effect on tumor growth rate.

Long-term drug distribution studies showed that multiple weekly administrations produced some significant drug accumulation in the heart but did not enhance the accumulation in the liver, skeletal leg muscle, or tumors over the course of four weeks of consecutive weekly injections of Dox-encapsulated NanoDeliv®. Pharmacokinetics showed that the initial Dox concentrations are highest in the heart and the liver, but they quickly decrease to less than one-fifth their initial concentration within the first 24 hours. After 24 hours, Dox concentration remains the greatest in the tumors, regardless of whether they received ultrasound or not.

Application of US alone or the use of empty drug carrier produced no significant effect upon tumor growth rate or the rat lifespan.

Acknowledgments

This research was support by NIH grant R01CA98138.

References

- 1.Hernot S, Klibanov AL. Microbubbles in Ultrasound-Triggered Drug and Gene Delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2008;60(10):1153–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husseini GA, Pitt WG. Micelles and Nanoparticles in Ultrasonic Drug and Gene Delivery. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2008;60(10):1137–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu JR, Nyborg WL. Ultrasound, Cavitation Bubbles and Their Interaction with Cells. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2008;60(10):1103–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husseini GA, Diaz MA, Richardson ES, Christensen DA, Pitt WG. The Role of Cavitation in Acoustically Activated Drug Delivery. J Controlled Release. 2005;107(2):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Husseini GA, Myrup GD, Pitt WG, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY. Factors Affecting Acoustically-Triggered Release of Drugs from Polymeric Micelles. J Controlled Release. 2000;69:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman HR, Nguyen DX, Kahn S, Prausnitz MR. Ultrasound-mediated disruption of cell membranes. I. Quantification of molecular uptake and cell viability. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;110(1):588–596. doi: 10.1121/1.1376131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa K, Tachibana K, Uchida T, Tai T, Yamashita N, Tsujita N, Miyauchi R. High-resolution scanning electron microscopic evaluation of cell-membrane porosity by ultrasound. Med Electron Microsc. 2001;34(4):249–253. doi: 10.1007/s007950100022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prentice P, Cuschierp A, Dholakia K, Prausnitz M, Campbell P. Membrane disruption by optically controlled microbubble cavitation. Nat Phys. 2005;1(2):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlicher RK, Radhakrishna H, Tolentino TP, Apkarian RP, Zarnitsyn V, Prausnitz MR. Mechanism of intracellular delivery by acoustic cavitation. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2006;32(6):915–924. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.02.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stringham SB, Viskovska MA, Richardson ES, Ohmine S, Husseini GA, Murray BK, Pitt WG. Over-Pressure Suppresses Ultrasonic-Induced Drug Uptake. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2009;35(3):409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tachibana K, Uchida T, Ogawa K, Yamashita N, Tamura K. Induction of cell-membrane porosity by ultrasound. Lancet. 1999;353:1409. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y, Kumon RE, Cui J, Deng CX. The Size of Sonoporation Pores on the Cell Membrane. Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 2009;35(10):1756–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Church CC. Frequency, pulse length, and the mechanical index. Acoust Res Lett Onl. 2005;6(3):162–168. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husseini GA, Diaz de la Rosa MA, Gabuji T, Zeng Y, Christensen DA, Pitt WG. Release of Doxorubicin from Unstabilized and Stabilized Micelles Under the Action of Ultrasound. J Nanosci Nanotech. 2007;7(3):1–6. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husseini GA, Christensen DA, Rapoport NY, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic release of doxorubicin from Pluronic P105 micelles stabilized with an interpenetrating network of N,N-diethylacrylamide. J Controlled Rel. 2002;83(2):302–304. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00203-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marin A, Muniruzzaman M, Rapoport N. Acoustic activation of drug delivery from polymeric micelles: effect of pulsed ultrasound. J Controlled Rel. 2001;71:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munshi N, Rapoport N, Pitt WG. Ultrasonic activated drug delivery from Pluronic P-105 micelles. Cancer Letters. 1997;117:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pruitt JD, Pitt WG. Sequestration and ultrasound-induced release of doxorubicin from stabilized pluronic P105 micelles. Drug Deliv. 2002;9(4):253–258. doi: 10.1080/10717540260397873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson JL, Roeder BL, Carmen JC, Roloff F, Pitt WG. Ultrasonically Activated Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery in a Rat Model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7280–7283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapoport N, Pitt WG, Sun H, Nelson JL. Drug delivery in polymeric micelles: from in vitro to in vivo. J Control Rel. 2003;91(1–2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pruitt JD, Husseini G, Rapoport N, Pitt WG. Stabilization of Pluronic P-105 Micelles with an Interpenetrating Network of N,N-Diethylacrylamide. Macromolecules. 2000;33(25):9306–9309. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Staples BJ, Roeder BL, Husseini GA, Badamjav O, Schaalje GB, Pitt WG. Role of Frequency and Mechanical Index in Ultrasound-Enhanced Chemotherapy of Tumors in Rats. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2009;64:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s00280-008-0910-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Danesi R, Fogli S, Gennari A, Conte P, Del Tacca M. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of the anthracycline anticancer drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(6):431–444. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linkesch W, Weger M, Eder I, Auner HW, Pernegg C, Kraule C, Czejka MJ. Long-term pharmacokinetics of doxorubicin HCl stealth liposomes in patients after polychemotheraphy with vinorelbine, cyclophosphamide and prednisone (CCVP) European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics. 2001;26(3):179–184. doi: 10.1007/BF03190394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tavoloni N, Guarino AM. Biliary and Urinary Excretion of Adriamycin in Anesthetized Rats. Pharmacology. 1980;20:256–267. doi: 10.1159/000137371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kabanov AV, Alakhov VY. Pluronic Block Copolymers in Drug Delivery: from Micellar Nanocontainers to Biological Response Modifiers. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 2002;19(1):1–73. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v19.i1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.USP, editor. Adriamycin (DOXOrubicin HCl) for Injection. Bedford, OH: Ben Venue Laboratories; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alakhov V, Klinski E, Li SM, Pietrzynski G, Venne A, Batrakova E, Bronitch T, Kabanov A. Block copolymer-based formulation of doxorubicin. From cell screen to clinical trials. Colloid Surface B. 1999;16(1–4):113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jewell RC, Khor SP, Kisor DF, LaCroix KAK, Wargin WA. Pharmacokinetics of RheothRx injection in healthy male volunteers. J Pharm Sci. 1997;86(7):808–812. doi: 10.1021/js960491e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacquet P, Stuart OA, Dalton R, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Effect of intraperitoneal chemotherapy and fibrinolytic therapy on tumor implantation in wound sites. J Surg Oncol. 1996;62(2):128–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9098(199606)62:2<128::AID-JSO9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martin F, Caignard A, Jeannin JF, Leclerc A, Martin M. Selection by Trypsin of Two Sublines of Rat Colon Cancer Cells Forming Progressive or Regressive Tumors. Int J Cancer. 1983;32:623–627. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910320517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alvarez-Cedron L, Sayalero ML, Lanao JM. High-performance liquid chromatographic validated assay of doxorubicin in rat plasma and tissues. J Chromatogr B. 1999;721(2):271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(98)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajeev D. MS Thesis. Brigham Young University; Provo, Utah: 2007. Separate and Joint Anaysis of Longitudinal and Survival Data; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dreher MR, Liu WG, Michelich CR, Dewhirst MW, Yuan F, Chilkoti A. Tumor vascular permeability, accumulation, and penetration of macromolecular drug carriers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2006;98(5):335–344. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seymour LW. Passive Tumor Targeting of Soluble Macromolecules and Drug Conjugates. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems. 1992;9(2):135–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kruskal J, Miner B, Goldberg SN, Kane RA. Optimization of Conventional Clinical Ultrasound Parameters for Enhancing Drug Delivery into Tumors. Radiology. 2002;225(Suppl S):587–588. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frenkel V, Etherington A, Greene M, Quijano J, Xie JW, Hunter F, Dromi S, Li KCP. Delivery of liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil) in a breast cancer tumor model: Investigation of potential enhancement by pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound exposure. Acad Radiol. 2006;13(4):469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2005.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuh EL, Shulman SG, Mehta SA, Xie JW, Chen LL, Frenkel V, Bednarski MD, Li KCP. Delivery of systemic chemotherapeutic agent to tumors by using focused ultrasound: Study in a murine model. Radiology. 2005;234(2):431–437. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2342030889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dromi S, Frenkel V, Luk A, Traughber B, Angstadt M, Bur M, Poff J, Xie JW, Libutti SK, Li KCP, Wood BJ. Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound and low temperature sensitive liposomes for enhanced targeted drug delivery and antitumor effect. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(9):2722–2727. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Husseini GA, Rapoport NY, Christensen DA, Pruitt JD, Pitt WG. Kinetics of ultrasonic release of doxorubicin from Pluronic P105 micelles. Coll Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2002;24:253–264. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marin A, Muniruzzaman M, Rapoport N. Mechanism of the ultrasonic activation of micellar drug delivery. J Control Rel. 2001;75:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen WS, Lu XC, Liu YB, Zhong P. The effect of surface agitation on ultrasound-mediated gene transfer in vitro. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;116(4):2440–2450. doi: 10.1121/1.1777855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehier-Humbert S, Bettinger T, Yan F, Guy RH. Plasma membrane poration induced by ultrasound exposure: Implication for drug delivery. Journal of Controlled Release. 2005;104(1):213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]