Abstract

Background

The American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) established guidelines for fertility preservation for cancer patients. In a national study of US oncologists, we examined attitudes towards the use of fertility preservation among patients with a poor prognosis, focusing on attitudes towards posthumous reproduction.

Method

A cross-sectional survey was administered via mail and Internet to a stratified random sample of US oncologists and measured demographics, knowledge, attitude, and practice behaviors regarding posthumous reproduction and fertility preservation with cancer patients of childbearing age.

Results

Only 16.2% supported posthumous parenting, while the majority (51.5%) did not have an opinion. ANOVA analyses indicated attitudes towards posthumous reproduction were significantly related to physician practice behaviors and dependent on oncologists’ knowledge of ASCO guidelines.

Conclusions

Physician attitudes may conflict with following recommended guidelines and may reduce the likelihood that some patients receive information about fertility preservation. Further education may raise physicians’ awareness of poor prognostic patients’ interest in pursuing this technology.

Keywords: posthumous assisted reproduction, poor prognosis, infertility, cancer, oncologist, attitudes

Introduction

Cancer and Infertility

Improvements in treating cancer have resulted in an increased population of cancer survivors. Unfortunately, these treatments have detrimental effects on reproductive functioning. In females, cancer treatments can interfere with the functioning of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus or cervix, affect hormone balance, or decrease the number of primordial follicles (Lee, Schover et al. 2006; Oktay, Beck et al. 2008). Male infertility as a result of cancer treatment results from damaged or depleted germinal stem cells resulting in compromised sperm number, motility, morphology, and DNA integrity (Lee, Schover et al. 2006). Rates of infertility and comprised fertility after cancer treatment depend on a number of factors including age, sex, cancer site, treatment type, treatment dose, and pretreatment fertility of the patient (Wallace, Anderson et al. 2005; Lee, Schover et al. 2006). Estimated risk of infertility is 40–80% in female cancer patients of childbearing age (Sonmezer and Oktay 2006) and 30–75% in male cancer patients (Schover, Martin et al. 1999).

Cancer and Fertility Preservation

Fortunately, fertility preservation (FP) options are available that allow for storage of reproductive material in hopes of future parenthood. The established methods of fertility preservation are sperm cryopreservation and embryo cryopreservation (Lee, Schover et al. 2006; Oktay, Beck et al. 2008). Ooctye freezing is considered an experimental option, but can be considered for women who do not have a partner and do not wish to use donor sperm (Lee, Schover et al. 2006; Oktay, Beck et al. 2008). Both embryo and ooctye freezing procedures may delay cancer treatment for approximately two to six weeks. This delay in treatment may not be a viable option for some patients, particularly those with advanced stages of disease (Pfeifer and Coutifaris 1999).

Patients’ Concern with Fertility Loss

Although some health care providers have questioned the importance of fertility loss amidst a cancer diagnosis, research shows that cancer survivors desire a return to normal life post-treatment and are very much concerned with fertility loss and interested in fertility preservation options. Infertility caused by cancer treatments is one of the most distressing side effects of cancer treatment, adversely affect quality of life (Pfeifer and Coutifaris 1999; Schover, Brey et al. 2002a; Partridge, Gelber et al. 2004) and causing increased emotional distress (Rieker, Fitzgerald et al. 1990; Schover, Martin et al. 1999; Schover, Brey et al. 2002a; Partridge, Gelber et al. 2004; Wallace, Anderson et al. 2005; Lee, Schover et al. 2006; Sonmezer and Oktay 2006; Oktay, Beck et al. 2008). Additionally, cancer patients are interested in parenthood and are specifically interested in having biological children (Pfeifer and Coutifaris 1999; Wallace, Anderson et al. 2005; Sonmezer and Oktay 2006; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2008). Research has shown that banking sperm or embryos is a positive factor to help patients cope with cancer even if samples were never used (Bahadar 2000; Saito, Suzuki et al. 2005). Knowledge of available fertility preservation often provides patients with a sense of reassurance about their future (Bahadar 2000). Should no preservation options be available, discussions with an infertility specialist provide the opportunity for mourning the loss of fertility and considering other options (Schover, Martin et al. 1999; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2008).

Oncologist’s Role

Considering oncologist role in treatment decisions and communication of treatment side effects, both the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) issued guidelines which highlight the importance of patient education and recognizing the oncologists as the main communicator of fertility related information. (Ethics Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine 2005; Lee, Schover et al. 2006) ASCO guidelines state that

“As part of the informed consent before cancer therapy, oncologists should address the possibility of infertility with patients treated during their reproductive years and be prepared to discuss possible fertility preservation options or refer appropriate and interested patients to reproductive specialist”.

ASRM similarly states that physicians should inform cancer patients about fertility future fertility and fertility preservation options prior to treatment. In sum, these guidelines stress that addressing this issue with patients is an important aspect of quality cancer care and that physicians must provide timely information (Lee, Schover et al. 2006). Despite these guidelines, recent research suggests oncologists are not always providing or referring for fertility information to their patients (Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2009). Many factors may contribute to the lack of discussion of fertility issues between patients and physicians, including the physician’s specialty, age, knowledge and attitudes toward FP, or comfort with the topic (Schover, Brey et al. 2002b; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2007; Vadaparampil, Clayton et al. 2007; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2008; Vadaparampil, Quinn et al. 2008). The physician’s perception of a patient’s insurance status, availability of resources, and cost of procedures may also serve as barriers (Schover, Brey et al. 2002b; Vadaparampil, Clayton et al. 2007; Vadaparampil, Quinn et al. 2008). They may also be reluctant to have this discussion with patients who have a poor prognosis for survival (Pfeifer and Coutifaris 1999; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2007; King, Quinn et al. 2008).

Posthumous Assisted Reproduction (PAR)

Posthumous reproduction is a controversial topic that is complicated further by the lack of national legislation regarding posthumous reproduction in the US (Pennings, De Wert et al. 2006; Pennings, De Wert et al. 2007). While a few studies have suggested that physicians may have personal or ethical concerns with fertility preservation when used to conceive a child subsequent to the death of the patient, i.e., posthumous assisted reproduction (PAR) (Bahadur 1996; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2007; Vadaparampil, Clayton et al. 2007; Vadaparampil, Quinn et al. 2008), none evaluate these attitudes in a large national sample of oncology care physicians. As part of a larger national study focused on knowledge, attitudinal, and practice factors associated with discussion and referrals for fertility, preservation among cancer patients of childbearing age (Quinn, Vadaparampil, 2009), we explored attitudes, particularly toward posthoumous reproduction, as they related to discussion of FP with patients with a poor prognosis..

Methods

Sample

A stratified random sample of U.S. oncologists from the American Medical Association Masterfile was recruited by U.S. mail. The sample included physicians in specialties of hematology/medical oncology, gynecologic oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and musculoskeletal oncology. In addition to specialty, other eligibility criteria included: 1) graduation from medical school after 1945; 2) practicing medicine in the U.S. including Puerto Rico; and 3) those who list patient care as their primary job and locum tenens. The purpose of the main study was to assess oncologist’s patterns for discussion and referrals for fertility preservation in cancer patients of childbearing age. Those results are reported in another paper and a copy of the survey is available from the author (Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2009).

Recruitment

A three-phased recruitment approach patterned after the Dillman Method was utilized (Dillman, 1978). A $100 honorarium was offered to those completing the survey. Requests for honorarium could be made by returning the pre-addressed post card provided in the study packet or sending an email to study team with contact information.

Measure

A 53-item survey was developed to measure physicians attitudes, knowledge, barriers, and practice behaviors related to fertility preservation in cancer patients of childbearing age (16–44). See Quinn et al. 2009 for description of survey development and survey items (Dillman,1978). This study represents a sub-set of results focused on an attitude item measuring physicians attitudes towards posthumous reproduction and FP in patients’ with a poor prognosis in relation to practice behaviors that may enable FP.

FP Attitudes towards poor prognosis

Attitude towards FP in patients with a poor prognosis were assessed with the statement: “Patients with a poor prognosis should not pursue fertility preservation.” Physicians indicated agreement with the statements using 5 point Likert-style items (strongly agree to strongly disagree with a neither agree/disagree midpoint).

Participants were considered to have a favorable attitude toward FP in patients with a poor prognosis if they disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement. FP Attitudes towards Posthumous Reproduction. Attitude towards posthumous reproduction was measured by the statement, “I support posthumous parenting (child born from assisted reproduction subsequent to the patient’s death)”. Physicians indicated agreement with the statements using 5 point Likert-style items (strongly agree to strongly disagree with a neither agree/disagree midpoint).

Participants were considered to have an overall favorable attitude toward FP in patients with a posthumous reproduction if they agreed or strongly agreed with the statement.

Practice Behavior

Practice behaviors were assessed by the statement “I discuss fertility issues with patients whose prognosis is poor.” Physicians indicated agreement with statements on a five point Likert-style scale (always, often, sometimes, rarely, never).

Data Analyses

Frequencies were obtained to determine physician’s attitude towards posthumous reproduction and FP in patients with a poor prognosis. A correlation analysis was performed to determine if physicians that disagreed with a poor prognosis also disagreed with posthumous reproduction. Simple logistic regressions were used to determine if demographic or clinical characteristics related to a negative attitude towards posthumous parenting. Using a backwards elimination process, a multiple logistic regression was conducted to determine which variables were most related to negative attitude towards posthumous reproduction. Finally, ANOVA analyses were conducted to determine if attitude towards posthumous reproduction influenced practice behaviors. We also examined knowledge of ASCO guidelines and looked at the interaction of knowledge of ASCO guidelines and posthumous attitude to detect a possible interaction with attitudes and practice behaviors. Analyses were conducted by CK, TM, and JM using SPSS V 17.0 and all tests were two-sided with a declared significant at the 5% level.

Results

Sample Information

Of the 1,979 physicians recruited, 613 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 33%, after accounting for mail that were ineligible (n=6) and undeliverable (n=43), which is slightly higher than the average response rate in previous physician surveys (McCloskey, Tao et al. 2007; Thorpe, Ryan et al. 2009). Five participants were excluded from analyses for incomplete data. The analyses included a total of 511 physicians with the majority of the sample male (70.8%), White (76.7%), not Hispanic or Latino (94.5%), Catholic (29.8%), and had children (85.1%). Most physicians graduated from medical school in 1991 or earlier (68.2%) and specialized in medical oncology or hematology (31.9%). The primary practice location for most participants was a teaching hospital, university-affiliated cancer center, NCI-designated cancer center, or another location other than a private oncology practice (68.1%).

Attitude towards FP in patients with a poor prognosis

Among 516 participants, 232 (45.2%) neither agreed nor disagreed with FP in a poor prognosis. 117 (22.8%) agreed that patients with a poor prognosis should not pursue FP. 164 (32%) disagreed with the statement that patients with a poor prognosis should not pursue FP. Therefore, the majority of physicians had a neutral stance on the issue of patients with a poor prognosis pursuing FP”

Attitude towards posthumous parenting

Only 83 (16.2%) reported that they supported posthumous parenting, while the majority 263 (51.5%) did not have an opinion. 165 disagreed (32.3%) with posthumous reproduction.

The statement “Patient’s with a poor prognosis should not pursue fertility preservation” was significantly correlated with “I support posthumous parenting” suggesting that those who disagree with FP in a poor prognosis also disagree with posthumous reproduction (r = −.282, p<.001).

Demographic and clinical characteristics related to attitude towards PAR

Simple Bivariate Analyses

In logistic regressions, significant factors of having a negative attitude towards posthumous reproduction were Jewish Religion, year graduated from medical school, and specialty in gynecologic oncology (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association between demographic and practice characteristics in relation to negative attitude towards posthumous reproduction

| Demographic and Practice Characteristics | OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 0.76 | 0.50 – 1.16 | |

| Race | |||

| Other | 1.00 | ||

| White | 0.72 | 0.46 – 1.14 | |

| Religious Background | |||

| Catholic | 1.00 | ||

| Protestant | 0.77 | 0.48 – 1.24 | |

| Jewish* | 0.40 | 0.22 – 0.75 | |

| Atheist | 0.49 | 0.27 – 0.87 | |

| Other* | |||

| Year Graduated From Medical School * | |||

| 1991 or Earlier | 1.00 | ||

| 1992 or Later | 0.55 | 0.36 – 0.85 | |

| Specialty | |||

| Medical Oncology/Hematology | 1.00 | ||

| Gynecologic Oncology* | 1.712 | 1.03 – 2.84 | |

| Radiation Oncology | 1.24 | 0.73 – 2.11 | |

| Surgical Oncology | 1.41. | 0.83 – 2.40 | |

| Musculoskeletal/orthopedic Oncology | 0.73 | 0.19 – 2.72 | |

| Primary Practice Location | |||

| Private Oncology Practice | 1.00 | ||

| Teaching University and Affiliated NIH | 1.01 | 0.68 – 1.52 | |

| Practice Arrangement | |||

| Full/Part Owner | 1.00 | ||

| Employee | 0.81 | 0.56 – 1.19 | |

| Size of Practice Setting | |||

| Small (1–5 physicians) | 1.00 | ||

| Medium (6–15 physicians) | 1.00 | 0.62 – 1.60 | |

| Large (>16 physicians) | 1.36 | 0.88 – 2.10 | |

| Number of Oncology Patients Seen Per Week | |||

| <10 | 1.00 | ||

| >11 | 0.44 | 0.17 – 1.19 | |

| Have Children | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| No | 0.51 | 0.35 – 1.10 | |

| Aware of ASCO Guidelines* | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | ||

| No | 1.02 | 0.69 – 1.50 | |

Multivariate analyses

Physicians with a negative attitude towards posthumous parenting were compared against those who reported a favorable or neutral opinion towards posthumous parenting. Using the backward elimination model, factors that significantly predicted having a negative attitude towards posthumous parenting were years since graduation (p<.001) and Jewish religion (p<.001). Physicians that graduated prior to 1992 compared to physicians that graduated after 1992 were more likely to have a negative attitude towards posthumous parenting (OR=0.54; 95%CI, 0.35–0.83). Physicians with a Jewish religion were significantly less likely to have a negative attitude towards posthumous parenting compared to physicians with a Catholic religion (OR=5.01; 95%CI .285–.880).

Attitude towards PAR related to discussing FP in patients with a poor prognosis

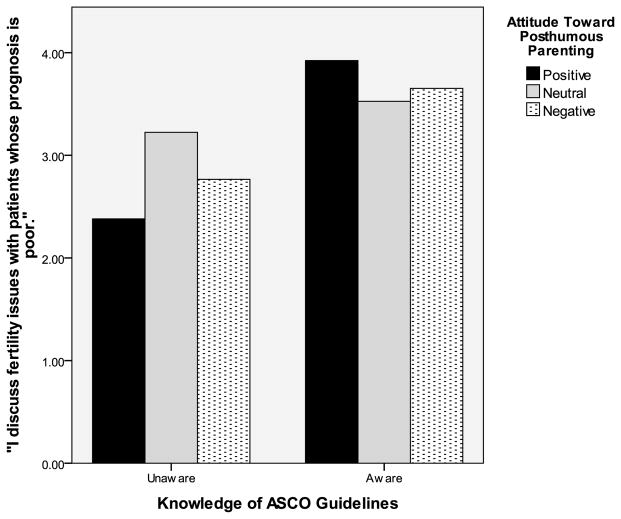

For secondary and exploratory purposes, we performed an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model to determine if a negative attitude towards PAR influenced practice behavior. To explore the nature of this relationship more closely, attitude towards posthumous reproduction at 3 levels (Negative: strongly agree, agree, Neutral: neither agree nor disagree; Positive: disagree, strongly disagree) was the predictor variable and the practice behavior question “I discuss fertility issues with patients whose prognosis is poor”, 1 rarely – 5 always. Attitude towards posthumous reproduction did not significantly predict discussion of fertility to patients with a poor prognosis (p > .05, Table 2). Knowledge of ASCO guidelines (Aware, Unaware) was entered as a predictor variable. There was a significant main effect in that physicians that were aware of guidelines were more likely to discuss fertility issues in patient whose prognosis is poor (p<.001; Table 3). Furthermore, there was an interaction with attitude towards posthumous parenting and knowledge of ASCO guidelines in predicting discussion of fertility issues to patients whose prognosis is poor (p<.01; Table 4). Physicians who had a negative attitude were more likely to discuss if they had knowledge of ASCO guideline compared to physicians that had negative attitudes and no knowledge of ASCO guidelines (Table 5, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics: Attitude towards posthumous parenting and in relation to discussion of fertility in patient whose prognosis is poor

| Attitude Towards Posthumous Parenting | Mean | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 3.152 | .177 | 2.805 | 3.499 |

| Neutral | 3.375 | .104 | 3.170 | 3.580 |

| Negative | 3.209 | .123 | 2.966 | 3.452 |

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics: Knowledge of ASCO guidelines predict discussion of fertility in patient whose prognosis is poor

| Knowledge of ASCO Guidelines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaware | 2.790 | .126 | 2.543 | 3.038 |

| Aware | 3.701 | .098 | 3.508 | 3.893 |

p<.001

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics: Attitude towards posthumous parenting and knowledge of ASCO guidelines predict discussion of fertility in patient whose prognosis is poor

| Attitude Towards Posthumous Parenting | Knowledge of ASCO Guidelines | Mean | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Unaware | 2.381 | .285 | 1.821 | 2.941 |

| Aware | 3.923 | .209 | 3.512 | 4.334 | |

| Neutral | Unaware | 3.224 | .159 | 2.910 | 3.537 |

| Aware | 3.526 | .134 | 3.263 | 3.790 | |

| Negative | Unaware | 2.766 | .190 | 2.392 | 3.140 |

| Aware | 3.652 | .157 | 3.343 | 3.961 | |

p>.01

Table 5.

ANOVA Model: Attitude towards posthumous parenting and knowledge of ASCO guidelines predict discussion of fertility in patient whose prognosis is poor

| Source | Type III Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected Model | 58.839a | 5 | 11.768 | 6.913 | .000 |

| Intercept | 2819.524 | 1 | 2819.524 | 1656.415 | .000 |

| Attitude Towards Posthumous Parenting | 2.878 | 2 | 1.439 | .845 | .430 |

| Aware of ASCO Guidelines | 55.451 | 1 | 55.451 | 32.576 | .000 |

| Interaction: Attitude Towards Posthumous Parenting, Aware Guidelines | 16.845 | 2 | 8.423 | 4.948 | .008 |

| Error | 565.125 | 332 | 1.702 | ||

| Total | 4442.000 | 338 | |||

| Corrected Total | 623.964 | 337 |

R Squared = .094 (Adjusted R Squared = .081)

Figure 1.

Attitude towards posthumous parenting and knowledge of ASCO guidelines in relation to discussion of fertility issues in patients with a poor prognosis

Discussion

These results indicate that most oncologists are uncertain about the issue of FP in patients with a poor prognosis and the idea of posthumous reproduction. This is understandable given that little has been published in the academic literature about this concept. Although it has not been explored in the context of cancer patients, it has been examined somewhat in patients with HIV. HIV patients also report a strong desire for a biological child, even in the event of their death and perceive medical professionals as likely to be unsupportive of this choice (Klein, Peña et al. 2003). Additionally, US military personnel often bank sperm prior to deployment and often these services are provided at no charge (Alvord 2003; Sperm banking 2007).

Oncologists’ personal attitudes regarding posthumous reproduction were related to referral of patients with a poor prognosis. Attitudes regarding poor prognosis and posthumous reproduction only related to discussing fertility issues in patients with a poor prognosis when ASCO guidelines were not known. Knowledge of guidelines, not whether they followed the guidelines or not, influenced whether physicians discussed fertility issues with patients with a poor prognosis. Guidelines can improve quality of care but do not always correlate with a change in clinical practice (Cheng, Nieman et al. 2007; Han, Klabunde et al. 2011). Religion was specifically related to beliefs about FP in patients with a poor prognosis and posthumous reproduction with physicians of Jewish religion having more negative attitudes. This is surprising given that several ethical perspectives on Judaism and assisted reproductive technology cite the Jewish religion as being favorable towards both (Schenker 2000; Schenker 2005). There are a wide range of religious views regarding posthumous reproduction and the associated assisted reproductive technology (ART). Islamic law supports use of ART only if both parents are still living (Serour and Dickens 2001). Catholics have not historically condoned ART; and may disapprove of posthumous reproduction because it implies insemination of an unmarried woman (Dillman 1978; McCloskey, Tao et al. 2007; Pennings, De Wert et al. 2007; Kramer 2009; Quinn, Vadaparampil et al. 2009; Thorpe, Ryan et al. 2009).

Although there is no national database or record keeping system, it is likely that only a few number of posthumously conceived children have occurred and few people are likely to seek posthumous use of stored gametes (Bahadur 1996). Discussions and referrals for fertility preservation among cancer patients of childbearing age may be significantly hindered by personal beliefs. There are limitations to the interpretation of our study data. It is likely that physicians who were more interested in the topic responded to the survey and thus there may be response bias. Additional, using a few single item indicators precludes our ability to evaluate situational considerations that oncologists face on a daily basis.

Conclusions

Oncologist should be cognizant of the adverse effects of cancer treatments on fertility, should also be aware of FP options, and offer referral to patients (Robertson 2005; Pennings, De Wert et al. 2006). Clearly, enabling a cancer patient with a poor prognosis to reproduce and possible posthumous reproduction presents ethical challenges. However, physicians’ perceptions of these challenges should not interfere with referral for fertility preservation. It is possible that the storage of gametes represents hope for the family or partners left behind in the event of death. One researcher reported this as a way to “make a bad death good” (Simpson 2001).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the American Cancer Society [RSGPB07-019-01-CPPB].

References

- Alvord V. Troops start trend with sperm banks. USA Today. 2003 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2003-01-26-sperm-inside_x.htm.

- Bahadar G. Fertility issues for cancer patients. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2000;169:117–122. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur G. Posthumous assisted reproduction: Posthumous assisted reproduction (PAR): cancer patients, potential cases, counselling and consent. Human Reproduction. 1996;11(12):2573–2575. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Nieman LZ, et al. Changes in perceived effect of practice guidelines among primary care doctors. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2007;13(4):621–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman D. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ethics Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. Fertility preservation and reproduction in cancer patients. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83:1622–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han PKJ, Klabunde CN, et al. Multiple Clinical Practice Guidelines for Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318202858e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King L, Quinn GP, et al. Oncology nurses’ perceptions of barriers to discussion of fertility preservation with patients with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(3):467–476. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein J, Peña JE, et al. Understanding the motivations, concerns, and desires of human immunodeficiency virus 1-serodiscordant couples wishing to have children through assisted reproduction. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;101(5 Part 1):987. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer AC. Sperm retrieval from terminally ill or recently deceased patients: a review. The Canadian Journal of Urology. 2009;16(3):4627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Schover LR, et al. American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(18):2917–2931. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey SA, Tao ML, et al. National survey of perspectives of palliative radiation therapy: role, barriers, and needs. The Cancer Journal. 2007;13(2):130. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31804675d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oktay K, Beck L, et al. 100 Questions and answers about cancer and fertility. Sudbury, Mass: Jones And Bartlett Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge AH, Gelber S, et al. Web-Based Survey of Fertility Issues in Young Women With Breast Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(20):4174–4183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings G, De Wert G, et al. ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law 11: posthumous assisted reproduction. Human Reproduction. 2006;21(12):3050. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings G, De Wert G, et al. ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law 13: the welfare of the child in medically assisted reproduction. Human Reproduction. 2007;22(10):2585. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer S, Coutifaris C. Reproductive technologies 1998: options available for the cancer patient. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1999;33:34–40. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199907)33:1<34::aid-mpo7>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, et al. Patient-physician communication barriers regarding fertility preservation among newly diagnosed cancer patients. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, et al. Discussion of fertility preservation with newly diagnosed patients: oncologists’ views. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1:146–155. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn G, Vadaparampil S, et al. Physician referral for fertility preservation with oncology patients: A national study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(35):5952–5957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieker P, Fitzgerald E, et al. Adaptive behavioral responses to potential inferility amond survivors of testis cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1990;8:347–355. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JA. Cancer and fertility: ethical and legal challenges. JNCI Monographs. 2005;2005(34):104. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Suzuki K, et al. Sperm cryopreservation before cancer chemotherapy helps in the emotional battle against cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:521–524. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker J. Women’s reproductive health: monotheistic religious perspectives. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2000;70(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenker JG. Assisted reproduction practice: religious perspectives. Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2005;10(3):310–319. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61789-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schover L, Brey K, et al. Knowledge and experience regarding cancer, infertility, and sperm banking in younger male survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002a;20:1880–1889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schover L, Brey K, et al. Oncologists’ attitudes and practices regarding banking sperm before cancer treatment. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002b;20:1890–1897. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schover L, Martin B, et al. Having Children after Cancer: A Pilot Survey of Survivors’ Attitudes and Experiences. Cancer. 1999;86:697–709. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990815)86:4<697::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serour GI, Dickens B. Assisted reproduction developments in the Islamic world. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2001;74(2):187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00425-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson B. Making ‘bad’ deaths ‘good’: the kinship consequences of posthumous conception. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2001;7:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sonmezer M, Oktay K. Fertility preservation in young women undergoing breast cancer therapy. Oncologist. 2006;11(5):422–434. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-5-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperm banking. Army Times. 2007 [Internet]. Available from: http://www.armytimes.com/offduty/health/online_ll_spermbank_box070219/

- Thorpe C, Ryan B, et al. How to obtain excellent response rates when surveying physicians. Family Practice. 2009;26(1):65. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil S, Clayton H, et al. Pediatric oncology nurses’ attitudes related to discussing fertility preservation with pediatric cancer patients and their families. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2007;24(5):255–263. doi: 10.1177/1043454207303878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil S, Quinn G, et al. Institutional availability of fertility preservation. Clinical Pediatrics. 2008;47(3):302–305. doi: 10.1177/0009922807309420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadaparampil S, Quinn G, et al. Barriers to fertility preservation among pediatric oncologists. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace W, Anderson R, et al. Fertility preservation for young patients with cancer: who is at risk and what can be offered? The Lancet Oncology. 2005;6:209–218. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]