Abstract

Soil microbes play an essential role in the forest ecosystem as an active component. This study examined the hypothesis that soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity would vary with the increasing stand ages in long-term pure plantations of Pinus elliottii. The phospholipid fatty acids (PLFA) combined with community level physiological profiles (CLPP) method was used to assess these characteristics in the rhizospheric soils of P. elliottii. We found that the soil microbial communities were significantly different among different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations. The PLFA analysis indicated that the bacterial biomass was higher than the actinomycic and fungal biomass in all stand ages. However, the bacterial biomass decreased with the increasing stand ages, while the fungal biomass increased. The four maximum biomarker concentrations in rhizospheric soils of P. elliottii for all stand ages were 18:1ω9c, 16:1ω7c, 18:3ω6c (6,9,12) and cy19:0, representing measures of fungal and gram negative bacterial biomass. In addition, CLPP analysis revealed that the utilization rate of amino acids, polymers, phenolic acids, and carbohydrates of soil microbial community gradually decreased with increasing stand ages, though this pattern was not observed for carboxylic acids and amines. Microbial community diversity, as determined by the Simpson index, Shannon-Wiener index, Richness index and McIntosh index, significantly decreased as stand age increased. Overall, both the PLFA and CLPP illustrated that the long-term pure plantation pattern exacerbated the microecological imbalance previously described in the rhizospheric soils of P. elliottii, and markedly decreased the soil microbial community diversity and metabolic activity. Based on the correlation analysis, we concluded that the soil nutrient and C/N ratio most significantly contributed to the variation of soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity in different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations.

Introduction

Pinus elliottii is a tree species native to the southeastern United States, and has been widely planted in China since 1980s due to its forage characteristics of high yield and fast growth [1]. Presently, it covers 11 provinces and has become one of the most important economic tree species in China [2]. However, dramatic yield decline and soil degradation observed in long-term pure plantations of P. elliottii have attracted an increasing level of interest from many ecologists and foresters [3]. Previous studies have shown that continuous cultivation of a single species resulted in degradation of the soil [4]. This phenomenon has been observed in many cultivated tree species, such as Cunninghamia lanceolata, Larix gmelinii, Pinus massoniana, Eucalyptus spp., and Populus spp. [5–9]. It has also been demonstrated that soil degradation inevitably results in the imbalance of soil microbial communities [10]. In addition, it is suggested that this imbalance further exacerbates soil degradation in long-term pure plantation cultivation [11]. Due to its long-term importance as a forestry crop in China, a number of studies have addressed above-ground characteristics of P. elliottii continuous pure plantations, including their growth regulation, biomass, and allelopathy [12–13]. However, restricted by soil ecosystem complexity and reliable experimental methods, the effects of P. elliottii long-term pure plantation patterns on the below-ground soil microbial community has not yet been reported.

Soil microbes play an active and essential role in the forest ecosystem [14]. The community structure and carbon metabolic activity of microbes have been shown as key indicators of soil quality. Since soil degradation is a common phenomenon in long-term pure plantations, understanding how soil microbial communities change with stand age helps to gain a better scientific understanding of how to best manage these man-made forests. This approach has gained momentum in the scientific community, with studies conducted on a variety of annual and a few perennial species. For example, Lu et al. discovered that without any soil-health management practices, long-term safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) plantations resulted in a shift of soil fertility from high (bacteria dominant) to low (fungi dominant) over time [15]. Li et al. found that the amount of fungal biomass increased markedly in Chinese fir plantations over successive rotations [16]. Furthermore, many abiotic factors like climate, pH and soil properties also contribute to explain the variation of aboveground community composition [17]. The vegetation types also profoundly affect the soil microbial communities [18, 19]. However, limited information is currently available on the research of main factor affecting the soil microbial community in Pinus elliottii plantations.

To describe the composition of the microbial communities in forest soils, culture-independent methods have been widely applied. Compared to other methods, phospholipids fatty acid analysis (PLFA) and community level physiological profiles (CLPP) methods are quantitative, have a relatively high throughput, and allow rapid analyses for the high number of samples needed for field-based microbial ecology investigations. In this study, we addressed the hypotheses that soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity would vary with increasing stand ages in pure plantations of P. elliottii. The goal of this study was to answer two questions: (1) how different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations affect soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity? and (2) What are the possible environmental factors leading to these differences? For these objectives, PLFA combined with CLPP methods were used to detect the variation of soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity in P. elliottii plantations. Our study will help to further understand ecological linkages between plant diversity aboveground and microbial diversity underground, and will therefore facilitate the establishment of scientific-based, effective management to achieve better ecosystem balance in man-made forests.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

This study has been approved by the Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, which takes care of the planning and protecting of Xiqin Forest Farm. The study did not involve any endangered or protected species. All the data in this study can be published and shared.

2.1 Site description

The experiment was conducted at the Xiqin Forest Farm (26°40′N, 118°10′E), Fujian Province, South China, an 11.6 km2 forested area in the subtropical monsoon region. This is one of the earliest P. elliottii plantations in China. The annual mean temperature is 19.4°C with an extreme high and low temperature of 39.0°C and -0.6°C respectively. Annual mean relative humidity is 80.2%, and the region has an average of 84 fog days per year. Annual precipitation reaches 1817.0 mm, most of which (57.56%) falls in summer (May through August). The soil is dominated by yellow-red soil.

2.2 Field sampling and soil physicochemical properties determination

Four P. elliottii plantations aged 3, 10, 18 and 25 years and established in 2011, 2004, 1996 and 1989, respectively, were selected for our study. We established three 20 m×20 m soil sampling plots for each stand age in September 2014. Sampling plots were selected to have similar environmental characteristics such as altitude, slope position, and slope aspect. Soil samples were randomly collected from 0–20 cm depths in each plot using a soil core sampler (diameter of 2.0 cm). Twenty cores were mixed into one soil sample, which was then sieved (2 mm) to remove soil impurities, hand-mixed and stored in plastic bags. Half of each soil sample was stored at 4°C for microbe characteristics analysis, and the other half was air-dried and sieved to determine soil pH, total organic carbon (TOC), total nitrogen (TN), available nitrogen (AN), total phosphorus (TP), available phosphorus (AP), total potassium (TK), and available potassium (AK) as described by Wu et al. [20]. The C/N ratio was also calculated.

2.3 Analysis of phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA)

PLFAs were extracted and derivatized as described by Zelles et al. [21]. Phospholipids were methylated by methanolic KOH to form fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs), and then analyzed using a 450GC/240MS system according to the procedure described by Patra et al. [22]. We used 19:0 of known concentration as an internal standard to quantify other PLFAs. The detailed experimental procedure was shown in S1 Appendix. The classification standard of indicative PLFAs representing gram-positive bacteria (Gram (+)), gram-negative bacteria (Gram (-)), actinomycetes, fungi and protozoans was carried out according to McKinley et al., Huygens et al. and Brockett et al. [23–25]. The Gram (+)/Gram (-) PLFA ratio and fungal/bacterial PLFA ratio (F/B) were also calculated.

2.4 Analysis of community level physiological profiles (CLPP)

Community level physiological profiling (CLPP) owes its beginnings to the development of the BIOLOG system in the late 1980s. In this study, the microbial catabolic diversity was assessed using BIOLOG Eco Microplate system, which contains 31 different carbon substrates, allowing triplicate samples arranged on a single 96-well plate [26]. The optical density (OD) at 590 nm was recorded at 24 h-intervals by automatic microplate reader in order to calculate the average well-color development (AWCD). The average well-color development is the sum of all 31 substrates’ utilization values by culturable bacteria, divided by 31. Based on the examination of the kinetic curves of the AWCD, 96 h measurements were chosen for further data analysis. The AWCD was determined as described by Wu et al. [20]. The detailed experimental procedure was shown in S2 Appendix.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Microbial activity in each microplate, expressed as average well-color development (AWCD) was determined by the equation , where C was the optical density within each well and R was the absorbance value of the control well. To test significant differences among soil samples, we performed one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Least Significant Difference (LSD) tests (P < 0.05) using DPS software version 7.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) and correlation analysis were performed using SPSS11.5 software.

Results

3.1 Soil physicochemical properties

Most soil physicochemical properties selected for analysis in this study were significantly different among the soil samples (P<0.05, Table 1). The pH values ranged from 5.78 to 6.36, indicating that all test soils were acidic. A significant decrease was observed in TOC, AN, AP, and TK with increasing stand ages. These indicator properties in 3 year stand soil were 34.27%, 91.48%, 89.89%, and 71.85%, more than that in 25 year stand soil respectively. Conversely, the value of C/N ratio increased with the increasing stand ages.

Table 1. Soil physicochemical properties in different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations.

| Stand ages | Ph | TOC/ (g·kg-1) | TN/ (g·kg-1) | AN/ (mg·kg-1) | TP/ (g·kg-1) | AP/ (mg·kg-1) | TK/ (mg·kg-1) | AK/ (mg·kg-1) | C/N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 6.36a | 21.86a | 1.12a | 38.22a | 0.56a | 3.76a | 23.99a | 109.11a | 19.51d |

| 10 | 6.01b | 19.54b | 0.95b | 34.09b | 0.53a | 3.05b | 20.06b | 89.17c | 20.56c |

| 18 | 5.82c | 17.37c | 0.81c | 27.84c | 0.41b | 2.67c | 19.97c | 96.24b | 21.44b |

| 25 | 5.78c | 16.28d | 0.75c | 19.96d | 0.33c | 1.98d | 13.96d | 76.08d | 21.70a |

Note: Values within a column followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P<0.05. The same is true in subsequent table columns.

3.2 PLFA determination of microbial community composition

Our results demonstrated a significant effect of stand age on soil microbial community composition. The Gram (+) bacteria, Gram (-) bacteria, Fungi, and actinomycete components are listed in Table 2, which according to S1 Table. A total of 18 different PLFAs were identified in this study. Among them, 10Me17:0 was only found in the 3 year stand soil, while 16:1ω9c was only found in 3 and 10 year stand soil. All other PLFAs were detected in all stand age soils. The content of bacterial PLFAs was highest in all soil samples, followed by fungi, and actinomycetes were the least detected. Total PLFAs, Gram(+) bacteria and Gram(−) bacteria all decreased with increasing stand ages, with values in 3 year stand soil equaling 29.68%, 127.79% and 81.96%, higher than that in 24 year stand soil respectively. Many bacterial PLFAs showed the same trend, including 16:1ω7c, 16:00, cy19:0, i18:0, 18:00, cy17:0, i17:0 and i17:0. The Gram (+)/Gram (-) ratio was less than 1 in all soil samples, indicating that the abundance of Gram (+) PLFAs was higher than that of Gram (-) PLFAs. The amount of fungal PLFAs showed an opposite trend, increasing across stand ages, resulting in a corresponding increase in the fungi/bacteria ratio as well. Actinomycete levels did not change significantly across the stand ages.

Table 2. Types and contents of PLFAs in different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations (ug·g-1).

| No. | Biomarkers | Microbial group | Stand ages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 10 | 18 | 25 | |||

| 1 | 18:1ω9c | Fungi | 6.91d | 8.23c | 13.78b | 15.26a |

| 2 | 16:1ω7c | Gram(-) bacteria | 11.36a | 9.21b | 7.94c | 6.44d |

| 3 | i14:0 | Gram(+) bacteria | 3.59a | 2.88b | 2.41c | 2.38c |

| 4 | 10Me18:0 | Actinomycete | 4.66a | 3.54b | 3.45b | 3.06c |

| 5 | 16:00 | Gram(-) bacteria | 7.55a | 5.79b | 4.32c | 2.96d |

| 6 | cy19:0 | Gram(-) bacteria | 25.67a | 23.93b | 19.26c | 15.17d |

| 7 | 18:3ω6c(6,9,12) | Fungi | 9.74d | 11.43c | 14.94b | 15.85a |

| 8 | 16:1ω9c | Gram(+) bacteria | 4.09a | 2.56b | - | - |

| 9 | i18:0 | Gram(+) bacteria | 5.66a | 4.78b | 4.04c | 3.44d |

| 10 | a17:0 | Gram(+) bacteria | 3.31a | 2.79b | 2.54c | 2.46c |

| 11 | 10Me16:0 | Actinomycete | 3.93a | 3.27c | 3.44b | 3.85a |

| 12 | 18:00 | Gram(-) bacteria | 2.73a | 2.34b | 1.25c | 0.76d |

| 13 | cy17:0 | Gram(-) bacteria | 8.77a | 7.81c | 7.96b | 5.49d |

| 14 | 18:3ω3 | Fungi | 1.67d | 1.94c | 2.53b | 3.52a |

| 15 | 10Me17:0 | Actinomycete | 1.42 | - | - | - |

| 16 | i17:0 | Gram(+) bacteria | 1.93a | 1.78b | 1.59c | 1.16d |

| 17 | 20:4ω6c(6,9,12,15) | Protozoon | 0.58b | 0.74a | 0.51b | 0.83a |

| 18 | 15:0 | Gram(+) bacteria | 4.45a | 3.78b | 0.93c | 0.67d |

| 19 | - | Total PLFA | 108.02a | 96.80b | 90.89c | 83.30d |

| 20 | - | Bacteria | 79.11a | 67.65b | 52.24c | 40.93d |

| 21 | - | Gram(+) | 23.03a | 18.57b | 11.51c | 10.11d |

| 22 | - | Gram(-) | 56.08a | 49.08b | 40.73c | 30.82d |

| 23 | - | Fungi | 18.32d | 21.60c | 31.25b | 34.63a |

| 24 | - | Actinomycete | 10.01a | 6.81b | 6.89b | 6.91b |

| 25 | - | Gram (+) / Gram (-) (%) | 41.06a | 37.84b | 28.26d | 32.80c |

| 26 | - | Fungi/ Bacteria (%) (F/B) | 23.16d | 31.93c | 59.82b | 84.61a |

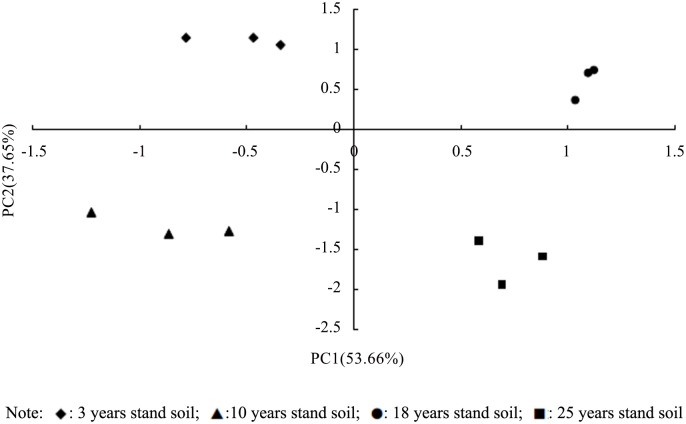

The content of all individual PLFAs was subjected to the principal component analysis (PCA) (Fig 1). Four soil samples were clearly distinguishable along the first principal component of the score plot, with 3 year stand soil and 10 year stand soil on the left side and 18 year stand soil and 25 year stand soil on the right side of the axis. PC1 accounted for 53.66% and PC2 accounted for 37.65% of the total variation, For PC1, lipid signatures cy19:0, a17:0, 18:1ω9c and 16:1ω7c had the highest loading scores, whereas for PC2, i14:0, i18:0 and cy17:0 had the highest loading scores.

Fig 1. Principal component analysis on PLFAs of different microbial groups in soils.

The figure describes the variance of soil microbial communities in the different stand ages of P. elliottii were clearly different from each other.

3.3 Analysis of community level physiological profiles (CLPP)

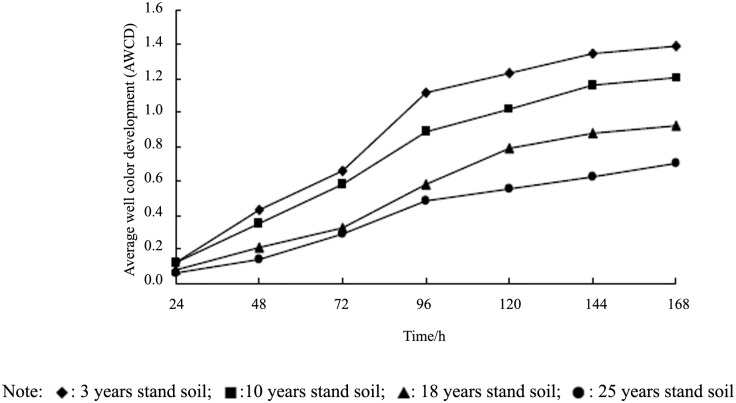

The AWCD values, as a measure of the total microbial activity, increased and showed a typical sigmoid course curve across the 168 h incubation for all samples (Fig 2, S2 Table). However, significant differences were observed in microbial activity rate of increase among the samples. The 3 year stand soil showed the highest utilization rate as indicated by a steep slope, whereas the 25 year stand soil showed the lowest utilization rate as indicated by a more gradual slope. Overall, the AWCD values significantly decreased with each increase in stand age measured (3 years > 10 years > 18 years > 25 years).

Fig 2. Changes of AWCD of soil microbe community with incubation time in soil samples of different stand ages.

The figure describes the AWCD of different stand soil change with incubation time, which were clearly different from each other.

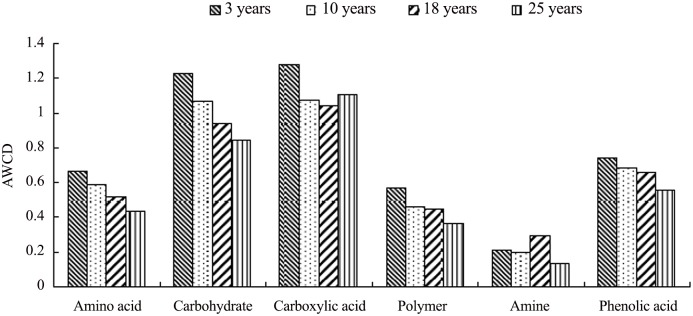

We divided 31 single carbon substrates into 6 categories: amino acids, polymers, phenolic acids, amines, carboxylic acids and carbohydrates as described by Chowdhury and Dick [27]. Overall, the sum of AWCD values within all 6 categories significantly decreased with each increase in stand age (3 years > 10 years > 18 years > 25 years) (Fig 3). Except for carboxylic acids and amines, the 96 h AWCD values of amino acid, carbohydrate, polymer and phenolic acid carbon substrate groups were highest in the 3 year stand soil and lowest in the 25 year stand soil. The levels of amino acids, carbohydrates, polymers, amines and phenolic acids of microbial communities from the 10 year and 18 year stand soil were higher than those from the 25 stand year soil. The Simpson index, Shannon-Wiener index, Richness index and McIntosh index in 3 year stand soil were all higher than that in 25 year stand soil, and these values also followed a significant sequence order 3 years > 10 years > 18 years > 25 years (Table 3).

Fig 3. Carbon source utilization by soil microbial community at different stand ages of P. elliottii plantations.

The figure describes the carbon source utilization of different stand soil microbial communities were clearly different from each other.

Table 3. Functional diversity indexes of soil microbial communities at different stand ages.

| Stand age | Simpson index | Shannon index | Richness index | McIntosh index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 years | 0.974 | 3.449 | 17.33 | 0.933 |

| 10 years | 0.926 | 3.286 | 15.19 | 0.876 |

| 18 years | 0.908 | 3.193 | 13.72 | 0.768 |

| 25 years | 0.875 | 3.051 | 11.09 | 0.669 |

3.4 The relationship between microbial community diversity and soil properties

Table 4 shows the relationship between microbial community diversity and soil properties. TOC and AN showed a significant positive correlation with the microbial community diversity, while C/N ratio showed a significant negative correlation. This indicates that soil C and N contents are very important factors to soil microbial diversity.

Table 4. Correlation analysis of microbial community diversity and soil properties.

| Simpson index | Shannon index | Richness index | McIntosh index | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | -0.395 | -0.347 | -0.384 | -0.290 |

| TOC/ (g·kg -1 ) | 0.956** | 0.981** | 0.947** | 0.965** |

| TN/ (g·kg -1 ) | 0.679 | 0.572 | 0.625 | 0.448 |

| AN/ (mg·kg -1 ) | 0.873* | 0.921** | 0.851* | 0.890* |

| TP/ (g·kg -1 ) | 0.709 | 0.878* | 0.842* | 0.731 |

| AP/ (mg·kg -1 ) | 0.930** | 0.755 | 0.801 | 0.819 |

| TK/ (mg·kg -1 ) | 0.871* | 0.830 | 0.744 | 0.731 |

| AK/ (mg·kg -1 ) | 0.677 | 0.938** | 0.885* | 0.711 |

| C/N | -0.926** | -0.907** | -0.949** | -0.980** |

Note:

*means P < 0.05, significant correlation;

**means P < 0.01, extremely significant correlation.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that soil microbial community diversity and metabolic activity decreased with increasing stand ages in P. elliottii plantations. The bacterial biomass decreased with the increasing stand ages, while the fungal biomass increased. The carbon source utilization rate and community diversity of soil microbes gradually decreased with increasing stand ages. Overall, both the PLFA and CLPP illustrated that the long-term pure plantation pattern exacerbated the microecological imbalance previously described in the rhizospheric soils of P. elliottii, and markedly decreased the soil microbial community diversity and metabolic activity. Similar trends were also reported in other tree species [28]. The importance of soil nutrient content in shaping microbial communities has been reported by a number of studies, and has been established as a key determinant for soil microorganism survival, species composition, and metabolism [6]. Therefore, the most important contributor to our observed reduction in microbial diversity and metabolic activity in P. elliottii stands is the decline of soil nutrient content. P. elliottii is a fast-growing tree species, and has a high requirement and utilization rate of soil nutrients to maintain this growth. Although litterfall can return nutrients to the soil and improve fertility to some extent, this rate of natural nutrient cycling is too slow [1]. In this study, the analysis of soil physicochemical properties showed that soil nutrient indicators such as TOC, AN, AP, and TK decreased with the increasing stand ages (Table 1). Correlation analysis also demonstrated close links between soil nutrient indicators and soil microbial diversity (Table 4). The correlation coefficient of community diversity with TOC and AN was greater than 0.945 (p<0.05) and 0.851 (p<0.05), respectively. Consequently, the decline of soil nutrient content inevitably leads to a decrease in soil microbial diversity. Furthermore, the effects of spatial change on soil nutrient content are also very important [29–32]. We will do further studies to compare the variation among different forest ecosystems in subtropical area.

In addition to nutrient content, soil C/N ratio is another important factor affecting soil microbial community structure. This study showed that the soil microbial community diversity was significantly negatively correlated with C/N ratio, indicating that high C/N ratio is not conducive to microbial growth. This result is also consistent with previous studies. For example, Högberg et al. found that soil C/N ratio and soil pH are important factors influencing soil microbial community composition [32]. Ushio et al. concluded that the variation of C/N ratio caused by tree species changed the soil microbial community structure profoundly [33]. P. elliottii litterfall contains many slowly-degrading components such as wax, cellulose, and lignin, and the C/N ratio in these substances are often relatively high [34]. Therefore, with the increasing stand ages, the accumulating litterfall increases the value of C/N ratio. Mudge et al. concluded the higher microbial C/N ratio indicated soil microorganisms activated by C-rich rhizodeposits with a high N demand and a greater potential for immobilization of N in the microbial biomass [35]. High C/N ratio leads to a lack of nitrogen in the soil, thereby inhibiting the activity of soil microorganisms. Furthermore, the soil tiny animals, plant root and seasonal variation might also cause or contribute to the differences. The F/B is also an indication of microbial community structure, and this proportion is known to change with changing soil environment conditions. Generally, the most abundant type of microorganism in healthy soils is bacteria, followed by actinomycetes and lastly fungi [36]. In this study, we found that during early developmental stages of P. elliottii plantations, adequate soil nutrition was beneficial to the reproduction of bacteria, which are favored in high-nutrient soil. Soil nutrient content decrease in increasing stand ages, however, resulted in an increase in fungal abundance, as fungal growth is favored in soil with lower fertility.

Our conclusions indicate that long-term monoculture plantations of P. elliottii result in a change in soil properties over time, and therefore cause a corresponding change in soil microbial community composition and metabolic activity. However, the CLPP and PLFA methods used here have limitations in their detection of soil microbial community characteristics. The experimental result of CLPP and PLFA are influenced by environmental change and physiological status of microbes under some environmental stresses. These results can be strengthened with future work combing with other soil microbial research methods such as terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP) and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Our studies help to more deeply understand the ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota, and thereby facilitate to establishment of an effective forest management practice for the improvement of forest ecosystem balance. Based on the results as mentioned above, improved management practices, such as microbial fertilizer application, organic matter amendment and enhanced plant diversity, could be used to relieve the consecutive monoculture problems of P. elliottii in future.

Supporting Information

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423487.

(DOC)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423488.

(DOC)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423489.

(XLS)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423490.

(XLS)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lin Sheng and Shen Lihua for experimental guidance during the study.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Izumi H, Cairney JWG, Killham K, Moore E, Alexander IJ, Anderson IC. Bacteria associated with ectomycorrhizas of slash pine (Pinus elliottii) in south-eastern Queensland, Australia. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2008; 282: 196–204. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01122.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ma ZQ, Liu JQ, Wang HM, Guo ZW. The growth pattern of Pinus elliottii plantation in central subtropical China. Acta Ecologica Sinica. 2011; 31: 1525–1537. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gonzalez-Benecke CA, Susaeta AI, Martin TA, Jokela EJ, Carter DR. Balancing revenue and nutrient removals in Pinus elliottii Engelm. stands managed for Pine straw and wood production. Forest Science. 2014; 60: 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dittrich S, Hauck M, Schweigatz D, Dorfler I, Huhne R, Bade C, et al. Separating forest continuity from tree age effects on plant diversity in the ground and epiphyte vegetation of a Central European mountain spruce forest. Flora. 2013; 208: 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou LL, Shalom ADD, Wu PF, Li SB, Jia YY, Ma XQ. Litterfall production and nutrient return in different-aged. Journal of Forest Research. 2015; 26: 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang WJ, Su DX, Qiu L, Wang HY, An J, Zheng GY, et al. Concurrent changes in soil inorganic and organic carbon during the development of larch, Larix gmelinii, plantations and their effects on soil physicochemical properties. Environmental Earth Sciences. 2013; 69: 1559–1570. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li Wen, Lei PF, Xiang WH, Yan WD, Liu SG. Soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in pure and mixed stands of Pinus massoniana and Cinnamomum camphora differing in stand age. Forest Ecology and Management. 2014; 328: 150–158. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen FL, Zheng H, Zhang K, Ouyang ZY, Lan J, Li HL, et al. Changes in soil microbial community structure and metabolic activity following conversion from native Pinus massoniana plantations to exotic Eucalyptus plantations. Forest Ecology and Management. 2013; 291: 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9. An R, Gong JR, You X, Ge ZW, Duan QW, Yan X. Seasonal dynamics of soil microorganisms and soil nutrients in fast-growing Populus plantation forests of different ages in Yili, Xinjiang, China. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology. 2011; 35: 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mendes R, Kruijt M, de Bruijn I, Dekkers E, Voort MV, Schneider JH, et al. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science. 2011; 332: 1097–1100. 10.1126/science.1203980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andersen R, Grassetc L, Thormannd MN, Rochefortb L, Francez AJ. Changes in microbial community structure and function following Sphagnum peatland restoration. Soil Biology & Biochemistry. 2010; 42: 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zhai L, Jokela EJ, Gezan SA, Vogel JG. Family, environment and silviculture effects in pure-and mixed-family stands of loblolly (Pinus taeda L.) and slash (P. elliottii Engelm. var. elliotttii) pine. Forest Ecology and Management. 2015; 337: 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chmura DJ, Tjoelker MG. Leaf traits in relation to crown development, light interception and growth of elite families of loblolly and slash pine. Tree Physiology. 2008; 28:729–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu Y, Zhang J, Yan BG, Huang X, Xu ZF, Wu FZ. Seasonal dynamics in soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen and microbial quantity in a forest-alpine tundra ecotone, Eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Chinese Journal of Plant Ecology. 2013; 36: 382–392. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu S, Quan W, Wang SM, Liu HL, Tan Y, Zeng GP, et al. Correlation of soil microbes and soil micro-environment under long-term safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) plantation in China. Journal of Environmental Biology. 2013; 34:471–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li MY, Hu CJ, Zhang J, Wang SL, Wang SJ. Microbial diversity in continuously planted Chinese fir soil. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2005; 16:1275–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vries FT, Manning P, Tallowin JRB, Mortimer SR, Pilgrim ES, Harrison KA, et al. Abiotic drivers and plant traits explain landscape-scale patterns in soil microbial communities. Ecology Letters. 2012; 11: 1230–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Monson RK, Lipson DL, Burns SP, Turnipseed AA, Delany AC, Williams MW, et al. Winter forest soil respiration controlled by climate and microbial community composition. Nature. 2006; 439: 711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zak DR, Holms WE, White DC, Peacock AD, Tilman D. Plant diversity, soil microbial communities, and ecosystem function: are there any links? Ecology. 2003; 84: 2042–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu LK, Li ZF, Li J, Khanb MA, Huang WM, Zhang ZX, et al. Assessment of shifts in microbial community structure and catabolic diversity in response to Rehmannia glutinosa monoculture. Applied Soil Ecology. 2013; 67: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zelles L, Bai QY, Rackwitz R, Chadwick D, Beese F. Determination of phospholipid-and lipopolysaccharide-derived fatty acids as an estimate of microbial biomass and community structures in soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 1995; 19: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Patra AK, Le Roux X, Grayston SJ, Loiseau P, Louault F. Unraveling the effects of management regime and plant species on soil organic carbon and microbial phospholipid fatty acid profiles in grassland soils. Bioresource Technology. 2008; 99: 3545–3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKinley VL, Peacock AD, White DC. Microbial community PLFA and PHB responses to ecosystem restoration in tallgrass prairie soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2005; 37: 1946–1958. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huygens D, Schouppe J, Roobroeck D, Alvarez M, Balocchi O, Valenzuela E, et al. Drying–rewetting effects on N cycling in grassland soils of varying microbial community composition and management intensity in south central Chile. Applied Soil Ecology. 2011; 48: 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brockett BFT, Prescott CE, Grayston SJ. Soil moisture is the major factor influencing microbial community structure and enzyme activities across seven biogeoclimatic zones in western Canada. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2012; 44: 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Haack SK, Garchow H, Klug MJ, Forney LJ. Analysis of factors affecting the accuracy, reproducibility, and interpretation of microbial community carbon source utilization patterns. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1995; 61: 1458–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chowdhury TR, Dick RP. Standardizing methylation method during phospholipid fatty acid analysis to profile soil microbial communities. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2012; 88: 285–291. 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang WD, Wang SL, Yan SK, Yang HX, Xu GB. Effects of root system and litter of Chinese fir on soil microbial properties. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology. 2009; 20: 2345–2350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun GQ. Pattern formation of an epidemic model with diffusion. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2012; 69: 1097–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun GQ, Wang SL, Ren Q, Jin Z, Wu YP. Effects of time delay and space on herbivore dynamics: linking inducible defenses of plants to herbivore outbreak. Scientific Reports. 2015; 5: 11246 10.1038/srep11246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sun GQ, Zhang G, Jin Z, Li L. Predator cannibalism can give rise to regular spatial pattern in a predator–prey system. Nonlinear Dynamics. 2009; 58: 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Högberg MN, Högberg P, Myrold DD. Is microbial community composition in boreal forest soils determined by pH, C-to-N ratio, the trees, or all three? Oecologia. 2007; 150: 590–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ushioa M, Wagaia R, Balserb TC, Kitayamaa K. Variations in the soil microbial community composition of a tropical montane forest ecosystem: Does tree species matter? Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 2013; 40: 2699–2702. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chen YL, Kang LH, Malajczuk N, Dell B. Selecting ectomycorrhizal fungi for inoculating plantations in south China: effect of Scleroderma on colonization and growth of exotic Eucalyptus globules, E. urophylla, Pinus elliottii and P. radiata . Mycorrhiza. 2006; 16: 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mudge PL, Schipper LA, Baisden WT, Ghani A, Lewis RW. Changes in soil C, N and delta N-15 along three forest-pasture chronosequences in New Zealand. Soil Research. 2014; 52: 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Corneo PE, Pellegrini A, Cappellin L, Roncador M, Chierici M, Gessler C, et al. Microbial community structure in vineyard soils across altitudinal gradients and in different seasons. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2013; 84: 588–602. 10.1111/1574-6941.12087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423487.

(DOC)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423488.

(DOC)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423489.

(XLS)

http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1423490.

(XLS)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.