Abstract

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) plays a critical role in reward-motivated behaviors. Repeated cocaine exposure dysregulates the dorsal mPFC, and this is thought to contribute to cocaine-seeking and relapse of abstinent abusers. Neuropathology of the mPFC also occurs in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals, and this is exaggerated in those who also abuse cocaine. The impact of the comorbid condition on mPFC neuronal function is unknown. To fill this knowledge gap, we performed a behavioral and electrophysiological study utilising adult male rats that self-administered cocaine by pressing a lever for 14 oncedaily operant sessions. Saline-yoked (SAL-yoked) rats served as controls. Cue reactivity (CR) was used to indicate drug-seeking, assessed by re-exposing the rats to cocaine-paired cues wherein non-reinforced lever pressing was quantified 1 day (CR1) and 18–21 days (CR2) after the 14th operant session. Only cocaine self-administration (COC-SA) rats showed CR. One day after CR2, brain slices were prepared for electrophysiological assessment. Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of dorsal (prelimbic) mPFC pyramidal neurons from COC-SA rats showed a significant increase in firing evoked by depolarizing currents as compared with those from SAL-yoked control rats. Bath application of the toxic HIV-1 protein transactivator of transcription (Tat) also depolarized neuronal membranes and increased evoked firing. The Tat-induced excitation was greater in the neurons from withdrawn COC-SA rats than in controls. Tat also reduced spike amplitude, and this co-varied with cocaine-seeking during CR2. Taken together, these novel findings provide support at the neuronal level for the concept that the increased excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons following cocaine self-administration drives drug-seeking and augments the neuropathophysiology caused by HIV-1 Tat.

Keywords: cue reactivity, excitability, over-excitation, patch-clamp recording

Introduction

Abstinent cocaine abusers report drug-craving when re-exposed to cocaine-associated cues (Grant et al., 1996). Similarly, rats withdrawn from cocaine self-administration (COC-SA) show drug-seeking behavior when re-exposed to cocaine-paired cues (Grimm et al., 2001). Such behavior is referred to as cue reactivity (CR). CR is associated with altered transmission in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) projection to the nucleus accumbens (Cornish et al., 1999; Koya et al., 2009; Loweth et al., 2013), and the prelimbic subregion of the mPFC (PrL) is an essential mediator of drug-seeking (McFarland & Kalivas, 2001; Chen et al., 2013). These studies suggest that insults to the mPFC can exaggerate cocaine-induced pathophysiology, and in so doing may promote drug-craving/seeking.

Prefrontal cortex (PFC) activity is disrupted in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive individuals (Melrose et al., 2008), and neuropathology is exaggerated in HIV-positive cocaine abusers as compared with non-abusing HIV-positive individuals (Davies et al., 1997; Ferris et al., 2008). Although potential differences in cocaine-craving between HIV-positive and HIV-negative cocaine addicts have not been directly assessed, the comorbid condition does result in greater impairment on PFC-mediated cognitive tasks (Meyer et al., 2013). HIV-1-infected cells in the brain release proteins that are neurotoxic. One toxic protein coded by HIV-1 is transactivator of transcription (Tat) (Chang et al., 1997). Tat is found in the central nervous system of HIV-positive individuals even when serum CD4 levels are normalised with antiretroviral drugs (Mediouni et al., 2012). Tat excessively increases Ca2+ influx in neurons (Brailoiu et al., 2008; Napier et al., 2014). In mPFC pyramidal neurons, this results in increased firing and prolonged Ca2+ spikes mediated by voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channels (L-channels) (Napier et al., 2014). This pathophysiology probably reflects increases in the number of ion channels, as the number of cells that are immunoreactive for the Cav1.2-α1c subunit (pore-forming protein) of the L-channel is increased in the rat mPFC after a single intraventricular injection of Tat (Wayman et al., 2012). Moreover, Tat-induced pathophysiology is augmented in these neurons after non-contingent cocaine injections (Napier et al., 2014).

Drug-seeking behavior is more profound in COC-SA rats than in those receiving non-contingent cocaine injections (Grimm et al., 2000). This cocaine-seeking behavior increases progressively for up to 2 months during withdrawal (Grimm et al., 2001). It is unclear whether mPFC to accumbens projection neurons reflect these differential effects of the contingent and non-contingent cocaine exposure. The current study addressed these questions. We hypothesised that COC-SA followed by protracted withdrawal would elicit drug-seeking associated with abnormally increased responses of mPFC pyramidal neurons to excitatory stimuli. We also expected that the consequences of acute exposure to Tat, at concentrations that increase pyramidal neuron activity (Napier et al., 2014), would be enhanced by protracted withdrawal from COC-SA. We found that withdrawal from COC-SA resulted in a more vulnerable mPFC state than that observed with non-contingent cocaine administration.

Materials and methods

Animals

Fifty adult male Sprague Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN, USA); they weighed 200–225 g upon arrival, and were used for COC-SA or saline-yoked (SAL-yoked) experiments. In addition, three adult rats weighing 325–350 g were purchased and used to test the stability of electrophysiology recordings as untreated controls. All rats were habituated for a minimum of 3 days prior to any treatment. Rats were housed two per cage under a 12-h light/dark cycle in an environmentally controlled facility; food and water were provided ad libitum. Rats were handled in accordance with the procedures established in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, Washington DC, USA), and the protocols were approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Procedures related to operant tasks

Procedures for surgery, self-administration and CR followed our previously published protocols for methamphetamine (Graves & Napier, 2011, 2012), adopted for cocaine. Each is briefly overviewed below.

For surgery, rats were anesthetised with isoflurane, and implanted with custom-built catheters constructed of silastic tubing (internal diameter, 0.3 mm; outside diameter, 0.64 mm; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) in the right jugular vein. The distal end of the 13.5-cm cannula extended subcutaneously over the mid-scapular region, and exited through an 11-mm metal guide cannula (22 gauge; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA). This port remained capped with a 5-mm section of silastic tubing (sealed on one end) and protected with an additional metal cap (Plastics One) between operant sessions. All rats were allowed to recover for a minimum of 5 days before training to acquire self-administered cocaine infusions (COC-SA, n = 25) or receiving saline through yoked infusions (SAL-yoked, n = 25). Catheters were flushed daily with 0.1–0.2 mL of sterile saline, and catheter patency was indicated by unrestricted ease of flushing and consistent COC-SA. Self-administration experiments began when rats recovered to pre-operative weights. Rats with catheters that had lost structural integrity during the study were excluded from the study (COC-SA, n = 4; SAL-yoked, n = 4). To ensure that electrophysiological evaluations were conducted only on brain slices from rats with reliable drug-taking, these rats were rejected from this study.

Operant procedures were conducted in chambers equipped with two levers (the left lever was designated as ‘active’ and the right one as ‘inactive’), a stimulus light above each lever, and a houselight on the opposite wall, enclosed in a sound-attenuating, ventilated cabinet (Med Associates, St Albans, VT, USA). A motor-driven syringe pump (Med Associates) delivered infusions by depressing a 10-mL syringe that was connected to the port on the back of the rats. The infusion tubing between the rat and the syringe was protected by a flexible metal tether that prevented disconnection or destruction of the tubing during the operant sessions.

COC-SA sessions lasted for 2 h/day. Each press of the active lever resulted in an infusion of 1.0 mg/kg/0.1 mL of cocaine (Griggs et al., 2010) delivered over 6 s, and was accompanied by illumination of a cue light above the lever. Subsequently, a house-light was illuminated and remained lit for 20 s, indicating a ‘time-out’ period. During the infusion and time-out period, active lever presses were recorded but had no programmed consequences. Inactive lever presses had no programmed consequences throughout the self-administration periods. The numbers of active lever presses, inactive lever presses and infusions were recorded.

Rats were trained to self-administer cocaine for 14 days. For the first 7 days, rats self-administered on a fixed-ratio 1 (FR1) schedule of reinforcement, in which each lever press led to one cocaine infusion; on day 8, all rats were changed to a fixed-ratio 5 (FR5) schedule, in which five lever presses resulted in one cocaine infusion. SAL-yoked rats received yoked infusions of saline according to an active lever press of a COC-SA partner, which was also associated with a 6-s illumination of the cue light. Both levers in the operant chamber for SAL-yoked rats were inactive; that is, neither the cue light nor the infusion pump of the yoked operant chamber was activated by press responses on the levers presented to the SAL-yoked rats in this box.

First, CR was assessed 1 day after the last operant session of COC-SA to determine a baseline measure of seeking behavior (CR1) (Loweth et al., 2013). A second CR session (CR2) was performed 18–21 days after the last session of COC-SA. Between CR1 and CR2, rats remained in their home cage. Responses to contextual cues (operant chamber) and explicit cues (i.e. the cue light, time-out light, and the sound of activation of the infusion pump) associated with COC-SA were assessed with a 1-h extinction-like CR test session. During CR tests, both groups of rats had control over the presentation of the cue light; however, no infusion of cocaine or saline was delivered. Saline-filled syringes were connected to the infusion lines to prevent air from entering during the CR tests. During CR2, rats that showed a > 50% increase in lever-pressing over that shown during CR1 were classified as ‘high-responders’.

Ex vivo electrophysiology

One day after the CR2 test, rats were anesthetised with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). The brains were then immediately excised and immersed in ice-cold, high-sucrose/low-Ca2+ sectioning solution consisting of 248 mm sucrose, 2.9 mm KCl, 2 mm MgSO4, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 26 mm NaHCO3, 0.1 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 2.5 mm kynurenic acid, and 1.0 mm ascorbic acid (pH 7.4–7.45; 335–345 mOsm). Coronal brain sections (300 µm) containing the mPFC were sliced in oxygenated (95% O2; 5% CO2) sectioning solution, and then transferred to a holding chamber containing normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid consisting of 125 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 25 mm NaHCO3, 1.25 mm NaH2PO4, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, and 15 mm glucose (pH 7.4; 305–315 mOsm) (Nasif et al., 2005b). After at least 1 h of incubation at room temperature, brain slices were transferred and anchored into a recording chamber, and perfused with oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid maintained at ~34 °C.

Recording electrodes were constructed from glass pipettes pulled with a horizontal pipette puller (p-97; Sutter Instruments, Novata, CA, USA). For experiments to determine the number of evoked action potentials and their electrophysiological characteristics, the electrodes were filled with an internal solution consisting of 120 mm potassium gluconate, 10 mm HEPES, 20 mm KCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 3 mm Na2ATP, 0.3 mm NaGTP, 0.1 mm EGTA, and 0.1% biocytin (pH 7.3–7.35; 280–285 mOsm). The filled electrode had a resistance of 4–6 MΩ. Pyramidal neurons were visually identified and located within the PrL according to landmarks illustrated in a rat brain atlas (Paxinos & Watson, 1998) on an Olympus BX-51 microscope at × 10 magnification. The whole-cell configuration was obtained during voltage-clamp recording. Voltage-clamp was then switched to current-clamp for recording of the action potentials evoked by membrane depolarization. Neurons that successfully formed a whole-cell configuration were allowed to stabilise for approximately 5–10 min. The recorded signals were amplified and filtered with a MultiClamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), digitised with a Digidata 1322 interface (Axon Instruments), and stored on a PC. Responses of mPFC pyramidal neurons were assessed with application of hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current pulses (500 ms), respectively, in the range of −500 pA to +400 pA with increments of 25 pA. To be included for data analysis, neurons from SAL-yoked rats had to show a stable resting membrane potential (RMP) that was more negative than −63 mV. Depolarizing current pulses that induced moderate membrane depolarization were used to mimic normal excitatory inputs to the neurons. Neurons also needed to generate an Na+-dependent action potential with an amplitude (peak) of > 60 mV measured from the threshold to the peak of the action potential that was evoked by the rheobase (the minimal depolarizing current that generated the first action potential) (Nasif et al., 2005b). The input resistance (Rin) was determined by fitting the change in membrane potential at the −200-pA current pulse with the Boltzmann charge–voltage equation to provide a value for ΔV.

Recombinant HIV-1 Tat1–86 was provided by the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (Germantown, MD, USA). We have previously determined the effects of 10–160 nm Tat on the excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons from adolescent rats (Napier et al., 2014). Pilot experiments with pyramidal neurons in brain slices from adult rats were conducted after protracted withdrawal from COC-SA for the current study indicated that such concentrations used for adolescent rats would be excessive; therefore, we assessed lower concentrations of Tat (1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 nm). These Tat concentrations are consistent with Tat levels found in the cerebrospinal fluid of HIV-positive patients (Xiao et al., 2000; Li et al., 2008). As developed in our prior study (Napier et al., 2014), Tat was continuously applied via a recycling system for each neuron studied, wherein each successive concentration of Tat was double the previous concentration. In our prior study, we determined that continuous, recycled perfusion of a single 40 nm concentration of Tat produced stable excitatory responses in rat pyramidal neurons that were similar to those generated by 40 nm administered with an escalating concentration protocol similar to that employed in the current study (Napier et al., 2014). Here, we conducted an additional study with untreated rats, and confirmed that this neuronal response similarity could be obtained with very low concentrations of Tat, i.e. 2.5 and 5 nm. We also confirmed that recordings were stable for the duration of the escalating concentration protocol (i.e. 40 min). For this purpose, neurons from untreated rats were continuously recorded, and, after establishment of baseline, data were collected at 10 min (the time when data from the first of the successive Tat perfusions were obtained) and 40 min (the time of the last data collection). We previously demonstrated that heat-inactivated Tat (i.e. at 85 °C for 30 min) does not alter pyramidal neuronal membrane properties or firing (Napier et al., 2014).

Immunohistochemistry

In some experiments, the morphology and anatomical location of the recorded neurons noted visually during recording were verified immunohistochemically by staining for biocytin, which was dialyzed into the neurons at the end of the experiment. For this purpose, the internal pipette solution contained 0.1% biocytin (Perez et al., 2006), which diffused into the assessed neurons during recording. Brain slices were immersion-fixed with 10% formalin, and subsequently rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline and incubated for 30 min in a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing 10% methanol and 3% H2O2. Biocytin-labeled neurons were revealed with 3,3’-diaminobenzadine + H2O2 (Heng et al., 2011).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. Data were analysed with graphpad prism v5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), sigmaplot v12 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA), and spss (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-squared tests were used for non-parametric comparison of spiking inhibition. Correlation analysis was used to compare changes in lever-pressing during CR1 vs. CR2 tests with the peak amplitude in response to 2.5 nm Tat. All other comparisons were performed with an anova, with Newman–Keuls tests for post hoc contrasts, and α < 0.05 was used to indicate significant differences. Following COC-SA or SAL-yoked treatments, behavioral data from the self-administration tests were analysed and compared by use of a two-way repeated-measures anova (rmanova), with the self-administration day and the number of active lever presses as the factors. For comparisons of active lever-pressing during CR sessions, a two-way rmanova was used. Membrane properties of the neurons from SAL-yoked rats were compared with those of neurons from COC-SA rats at baseline and during each Tat perfusion, by use of a two-way anova. Furthermore, a mixed-factors anova was used to analyse the current–spike response relationship and the current–voltage relationship for each concentration of Tat (chronic treatment was the between-groups factor, and Tat concentration and current applied were the within-group factors).

Results

COC-SA induced drug-seeking behavior

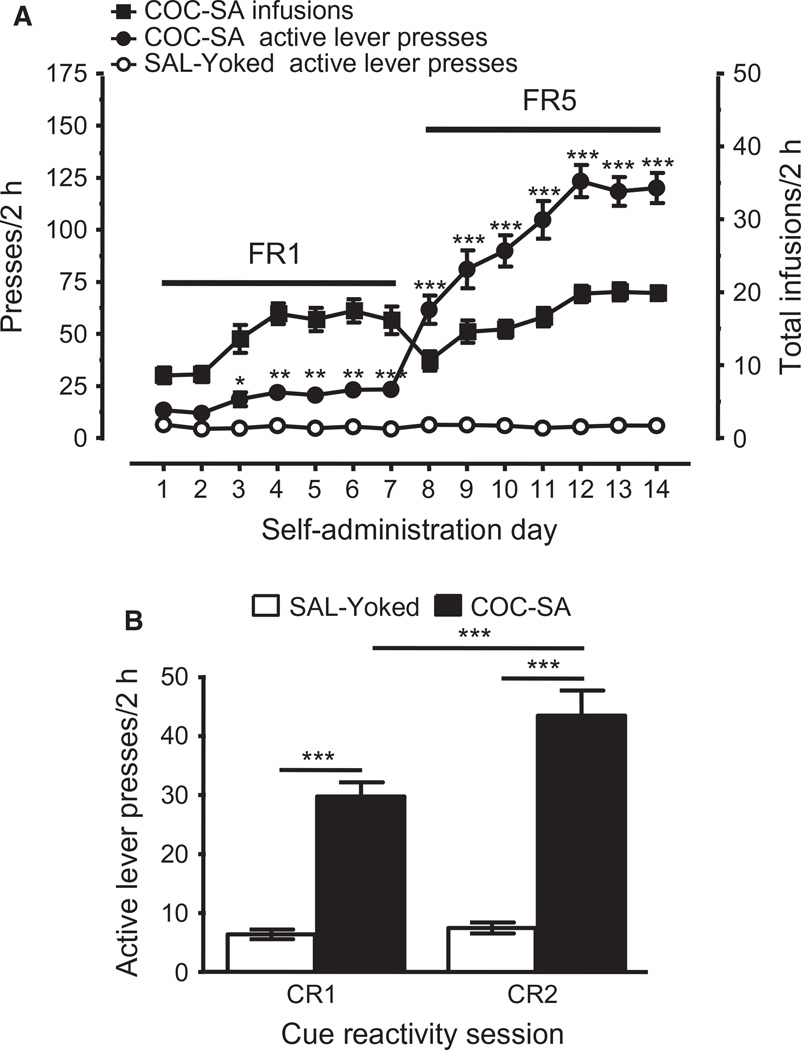

Twenty-one rats completed the COC-SA protocols, and these were paired with 21 SAL-yoked rats. The protocol resulted in effects of chronic treatment (F1,40 = 236.776, P < 0.001), self-administration day (F13,520 = 87.367, P < 0.001), and an interaction between these variables (chronic treatment × self-administration day: F13,520 = 85.320, P < 0.001). As shown on the left axis of Fig. 1A, a significant difference occurred in the number of active lever presses between COC-SA rats and SAL-yoked rats by day 3, indicating task acquisition. After switching to an FR5 schedule, active lever-pressing stabilised by day 11, and the rate was maintained until the last treatment day (i.e. day 14). As illustrated by the right axis of Fig. 1A, the number of cocaine infusions was similar for the FR5 and FR1 schedules (~20 infusions/2-h session).

Fig. 1.

COC-SA-induced drug-seeking behaviors were enhanced during prolonged abstinence. (A) Self-administration. Active lever presses (filled circles, left axis) and cocaine infusions (filled squares, right axis) for COC-SA rats (n = 21) reached stability on both FR1 and FR5 schedules of reinforcement. SAL-yoked rats (open circles, n = 21) did not show goal-directed lever-pressing. The number of active lever presses was significantly greater in COC-SA rats than that in SAL-yoked rats (two-way rmanova with a post hoc Newman–Keuls test: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001). (B) CR, assessed by two-way rmanova. During CR1, the number of presses on the lever previously paired with cocaine infusions and light cues was significantly increased in COC-SA rats (n = 21; filled bar) as compared with SAL-yoked rats (n = 21; open bar) with a post hoc Newman–Keuls test (***P < 0.001). An increase was also observed for COC-SA rats during CR2 (post hoc Newman–Keuls test, ***P < 0.001). Moreover, the number of active lever presses was significantly increased in COC-SA rats during CR2 as compared with CR1 (post hoc Newman–Keuls test: ***P < 0.001).

To determine whether COC-SA rats developed drug-seeking behavior during forced abstinence, cocaine-associated cues were presented, and pressing of the active lever in the absence of the drug was quantified for sessions conducted 1 day and 18–21 days after COC-SA (CR1 and CR2, respectively; Fig. 1B). Effects were observed for chronic treatment (F1,40 = 84.780, P < 0.001), day of CR test (F1,40 = 23.679, P < 0.001), and an interaction between these variables (chronic treatment × day of CR test: F1,40 = 17.193, P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that only COC-SA rats showed drug-seeking behavior during CR tests (the number of presses on the lever previously associated with cocaine infusions was significantly greater in COC-SA rats than in SAL-yoked rats during both CR1 and CR2). Moreover, the number of presses by COC-SA rats on the lever previously paired with cocaine infusions was significantly greater during CR2 than during CR1. For SAL-yoked rats, post hoc analysis did not reveal a significant difference in lever-pressing between CR1 and CR2. These results indicated that self-administered cocaine, but not yoked infusions of saline, induced drug-seeking behavior that was enhanced following a protracted period of forced abstinence.

Location and stability of recordings of mPFC pyramidal neurons

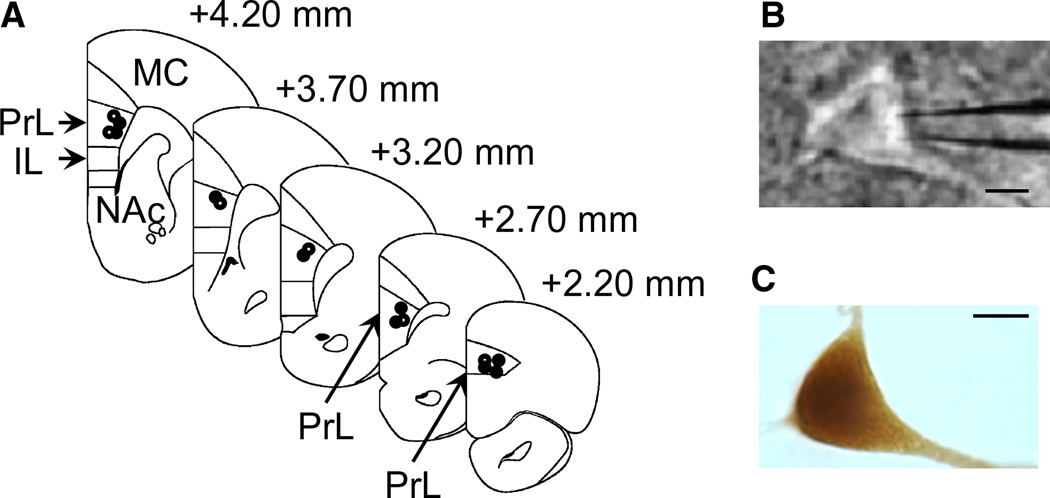

All recordings were conducted within the dorsal (PrL) mPFC (Fig. 2A), determined visually during the recording session (Fig. 2B). In some experiments (nine neurons from seven COC-SA rats, and six neurons from five SAL-yoked rats), the pyramidal morphology and location were confirmed by biocytin immunohistochemistry after the recording (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Location and morphology of the mPFC pyramidal neurons. (A) Illustrated sections of rat brain showing the locations where pyramidal neurons from COC-SA rats (n = 9; closed circles) or SAL-yoked rats (n = 6; open circles) were recorded and labeled with biocytin. (B) Representative image of a patched mPFC pyramidal neuron during recording (scale bar: 25 lm). (C) Representative recorded neuron identified with biocytin immunohistochemistry (scale bar: 25 µm). IL, infralimbic; MC, motor cortex; NAc, nucleus accumbens.

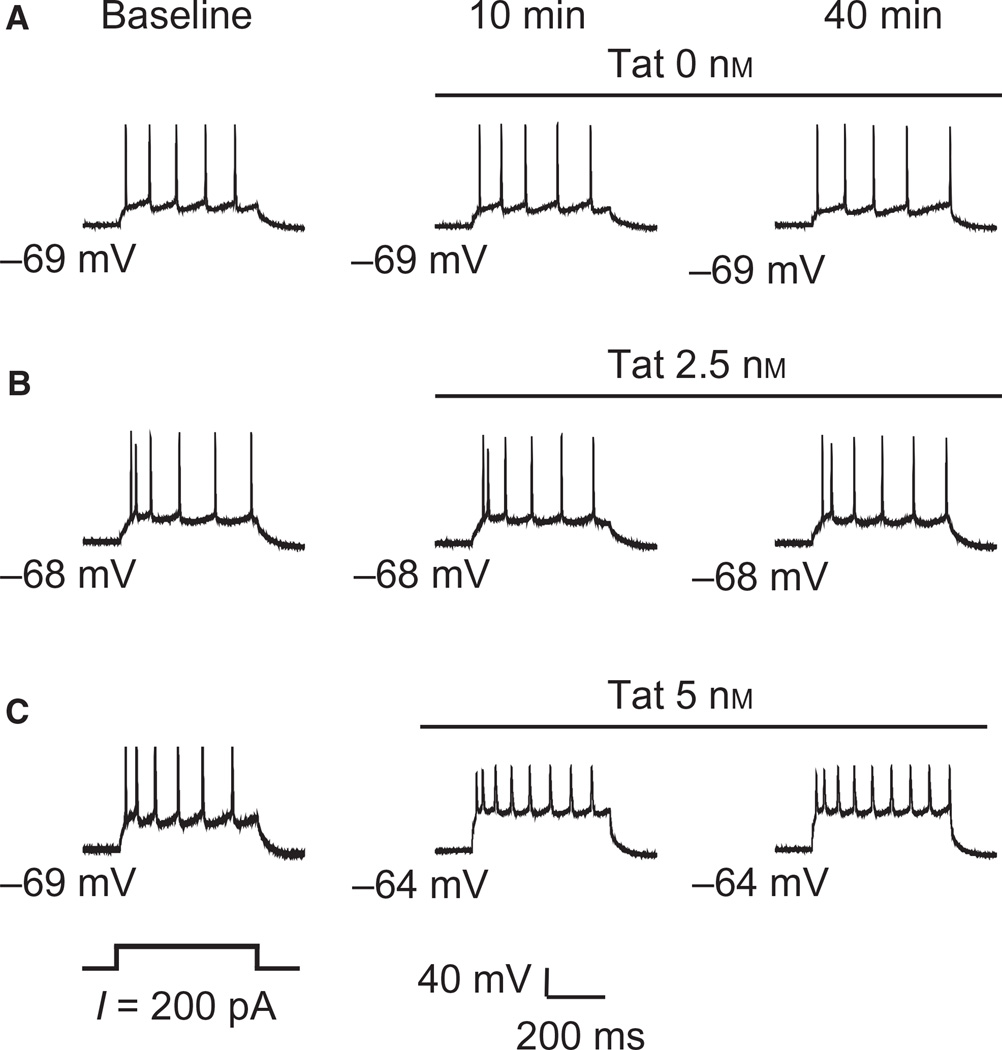

The number of action potentials evoked by a moderate depolarizing current pulse (200 pA) was not altered by continuous perfusion of artificial cerebrospinal fluid throughout the 50-min time frame needed to complete the experiments. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where firing was sampled at time points that corresponded to those used for data collection during perfusion of Tat, i.e. the baseline (Fig. 3A, left), and 10 and 40 min after the baseline recording had been completed (Fig. 3A, right). The recording was also stable during a 40-min perfusion of a single concentration of Tat, as shown in Fig. 3B for 2.5 nm and in Fig. 3C for 5 nm (three neurons from three untreated rats), and the response was similar after 10 and 40 min of Tat perfusion. Thus, maximal effects of bath-applied Tat were achieved by 10 min, and this effect was maintained for the duration of the 40-min recording period.

Fig. 3.

mPFC recordings were stable over the protocol duration. Illustrated are recordings of three separate mPFC pyramidal neurons (A–C) from untreated rats, showing baseline values, and values 10 and 40 min post-baseline. Each trace represents one neuron that was exposed to a single concentration of Tat for the duration of the recording protocol. (A) Action potentials evoked by a moderate depolarizing current (200 pA) remained stable in the absence of Tat perfusion (0 nm) for the 40-min protocol. (B) Evoked firing was not altered after 10 and 40 min of perfusion of bath-applied 2.5 nm Tat as compared with that recorded at baseline (0 min). (C) Tat bath-applied at 5 nm for 10 min reduced spike amplitude, and this response remained stable up to 40 min of perfusion.

Tat enhanced neuronal excitability in the mPFC from SAL-yoked rats

The effects of bath-applied Tat are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4. To summarise, the membrane properties altered by Tat were the RMP and rheobase. The RMP was significantly depolarized from baseline (nine neurons from eight rats) during infusion of 5 nm Tat (eight neurons from seven rats) and 10 nm Tat (eight neurons from seven rats). The rheobase was significantly reduced by 5 nm Tat (eight neurons from seven rats) and 10 nm Tat (eight neurons from seven rats). Perfusions of Tat at 1.25 nm (nine neurons from eight rats), 2.5 nm (eight neurons from seven rats) and 5 nm (six neurons from five rats) were not sufficient to alter the number of stimulation-evoked action potentials in neurons from SAL-yoked rats. Spiking during perfusion of 10 nm Tat (four neurons from four rats) is shown (Fig. 4A and B); however, owing to over-excitation/excito-toxicity at higher currents, these data were excluded from the analysis of the current–spike relationship. These results demonstrated a Tat-induced increase in the excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons.

Table 1.

Cocaine withdrawal potentiates Tat-induced alterations in membrane properties of mPFC pyramidal neurons

| Baseline |

1.25 nm Tat |

2.5 nm Tat |

5 nm Tat |

10 nm Tat |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAL-yoked | COC-SA | SAL-yoked | COC-SA | SAL-yoked | COC-SA | SAL-yoked | COC-SA | SAL-yoked | COC-SA | |

| No. of neurons | 9 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 10 |

| RMP(mV) | −69.1 ± 1.0 | −64.7 ± 1.1* | −68.3 ± 1.5 | −63.2 ± 1.2** | −67.7 ± 1.9 | −58.4 ± 1.3***,## | −64.3 ± 1.1*,$ | −56.2 ± 1.46***,### | −60.1 ± 2.0$ | −50.0 ± 2.4**,## |

| Rin (MΩ) | 116.5 ± 13.1 | 164.2 ± 10.4** | 123.6 ± 12.0 | 178.2 ± 14.9** | 128.6 ± 12.6 | 199.5 ± 19.8*** | 133.9 ± 17.8 | 191.2 ± 16.4** | 148.2 ± 16.8 | 200.8 ± 17.1***,### |

| Rheobase (pA) | 141.7 ± 17.2 | 66.1 ± 7.7*** | 127.8 ± 17.4 | 64.3 ± 7.3*** | 108.3 ± 17.2 | 55.4 ± 7.9*** | 81.3 ± 16.1$ | 50.0 ± 4.8*** | 80.6 ± 19.4$ | 40.4 ± 5.6** |

| Threshold (mV) | −40.0 ± 1.2 | −39.2 ± 2.0 | −38.1 ± 1.8 | −38.8 ± 1.9 | −39.2 ± 1.4 | −37.8 ± 2.0 | −41.8 ± 1.6 | −38.3 ± 2.4 | −40.4 ± 0.9 | −40.8 ± 4.0 |

| Peak amplitude (mV) | 81.2 ± 6.0 | 70.9 ± 3.3 | 74.6 ± 5.0 | 65.6 ± 4.0 | 72.7 ± 6.7 | 62.3 ± 4.8 | 65.7 ± 7.7$ | 58.1 ± 6.3* | 61.7 ± 7.3$ | 59.2 ± 8.1# |

Two-way anova with post hoc Newman–Keuls test:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01

P < 0.001 between chronic treatment;

P < 0.05 between Tat concentrations within the SAL-yoked group;

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01

P < 0.001 between Tat concentrations within the COC-SA group.

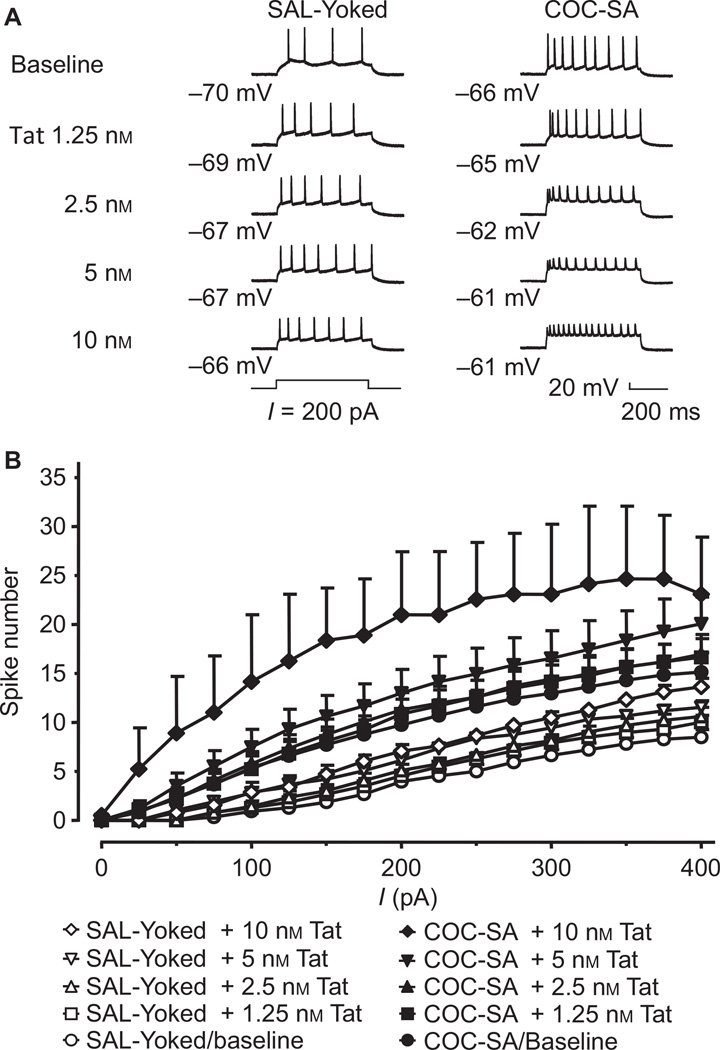

Fig. 4.

COC-SA potentiated Tat-mediated facilitation of evoked firing. (A) The illustrated traces show evoked firing in mPFC pyramidal neurons from SAL-yoked rats (left column) and COC-SA rats that showed CR (right column) in response to a 200-pA depolarizing current pulse, either in the absence of Tat (baseline) or during perfusion with 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 nm Tat. Tat increased the number of evoked action potentials in a concentration-dependent manner (1.25–10 nm), and also decreased the spike amplitude in a SAL-yoked neuron (left column). COC-SA also induced an increase in evoked firing (as compared with the SAL-yoked baseline), and enhanced the Tat effects on increasing the number of evoked action potentials and reducing the spike amplitude (right column). (B) The current–spike relationships indicate the number of evoked action potentials in response to a series of depolarizing current pulses (0–400 pA) at baseline (in the absence of Tat), and during perfusion with 1.25, 2.5, 5 and 10 nm Tat. There was no significant difference in the number of evoked action potentials between SAL-yoked neurons in the absence of Tat (SAL-yoked baseline, open circles; n = 9) and those exposed to bath application of 1.25 nm (n = 9; open squares), 2.5 nm (n = 8; open upward triangles) or 5 nm (n = 6; open downward triangles) Tat (mixed-model anova with post hoc Newman–Keuls test, P < 0.001). In neurons from rats withdrawn from COC-SA, the number of evoked action potentials was significantly increased in the absence of Tat as compared with SAL-yoked neurons (n = 14; filled circles; P < 0.001). Evoked action potentials were not altered in COC-SA neurons in response to Tat bath-applied at 1.25 nm (n = 14; filled squares) or 2.5 nm (n = 12; filled upward triangles), but were significantly increased in response to Tat at 5 nm (n = 8; filled downward triangles; P < 0.001) as compared with the COC-SA baseline. The neurons showing Tat-induced inhibition were excluded from the analysis of the current–spike relationships.

Tat-induced effects were enhanced in COC-SA rats

We assessed the effects of COC-SA during forced abstinence, with and without acute applications of Tat, on several passive and active electrophysiological characteristics of mPFC pyramidal neurons. Of the membrane properties measured, the RMP, rheobase and Rin showed significant changes (Table 1). The RMP was more depolarized in neurons from rats with a cocaine history than in neurons from SAL-yoked rats (chronic treatment: F1,81 = 48.112, P < 0.001). The RMP of the COC-SA neurons also showed greater sensitivity to the bath applications of Tat (Tat concentration: F4,81 = 12.230, P < 0.001), but there was no interaction between the two treatments (chronic treatment × Tat concentration: F4,81 = 0.875, P = 0.470). Post hoc analysis revealed that the RMP was significantly depolarized in COC-SA neurons as compared with SAL-yoked neurons at baseline and at all concentrations of bath-applied Tat. In addition, post hoc analysis indicated that Tat depolarized the RMP of COC-SA neurons at 2.5 nm (14 neurons from nine rats), 5 nm (11 neurons from seven rats) and 10 nm (10 neurons from six rats) as compared with the baseline condition. The rheobase was reduced by chronic treatment (F1,81 = 50.266, P < 0.001) and Tat concentration (F4,81 = 4.605, P = 0.002); however, there was no interaction between chronic treatment and Tat concentration (F4,81 = 1.030, P = 0.397). Post hoc analysis revealed that the rheobase was significantly reduced in COC-SA neurons at baseline and at all concentrations of bath-applied Tat as compared with SAL-yoked neurons at these intervals. Rin was increased by chronic treatment (F1,81 = 62.169, P < 0.001), but not by Tat concentration (F4,81 = 2.163, P = 0.080), and there was no interaction between chronic treatment and Tat concentration (F4,81 = 0.485, P = 0.746). Post hoc analysis revealed that Rin was significantly increased in COC-SA neurons at baseline and at all concentrations of bath-applied Tat as compared with SAL-yoked neurons at all time points. In addition, post hoc analysis revealed that Tat increased Rin of COC-SA neurons at 10 nm (10 neurons from six rats) as compared with baseline. Thus, COC-SA did not appear to have a synergistic action on the effects of Tat on the RMP, rheobase, or Rin.

Evoked firing was altered by chronic treatment (F1,1216 = 488.414, P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that COC-SA neurons (14 neurons from nine rats) showed more action potentials than SAL-yoked neurons (nine neurons from seven rats) in response to depolarizing currents of 175–400 pA (Fig. 4A, baseline; Fig. 4B, circles). Significant changes were induced by different Tat concentrations (F3,1216 = 33.253, P < 0.001) and current magnitudes (F16,1216 = 66.502, P < 0.001), but the Tat concentration × current interaction was not significant (F48,1216 = 0.293, P = 1.000). Post hoc analysis revealed that the number of evoked action potentials was significantly increased above baseline in response to 5 nm Tat (eight neurons from five rats) at depolarizing currents of 200 pA and 250–400 pA, but was not altered in response to Tat at 1.25 nm (14 neurons from nine rats) or 2.5 nm (12 neurons from nine rats; Fig. 4B) in COC-SA neurons. Tat was tested at 10 nm for two neurons (from two rats), and evoked spiking for these neurons is shown (Fig. 4B); however, these data were not included in the analysis of the current–spike relationship. As the neurons showing Tat-induced inhibition also showed action potential characteristics indicative of over-activation/excitotoxicity, these recordings were excluded from the analysis of the current–spike relationship. Statistically significant interactions occurred between chronic treatment and Tat concentration (F3,1216 = 8.995, P < 0.001) and between chronic treatment and current (F16,1216 = 4.142, P < 0.001), suggesting that cocaine and Tat produced a synergistic effect on neuronal excitability. It is noteworthy, however, that a statistically significant interaction was not obtained for chronic treatment × Tat concentration × current (F48,1216 = 0.070, P = 1.000). The lack of such an interaction here suggests a ceiling effect, during which the neurons lost the ability to respond further to higher currents and concentrations of Tat. These findings also suggest that protracted withdrawal from COC-SA has a synergistic effect on the ability of Tat to enhance action potential generation in mPFC pyramidal neurons.

The peak amplitude of the evoked action potentials was significantly reduced by chronic treatment (F1,81 = 6.916, P = 0.010) and by Tat concentration (F4,81 = 2.868, P = 0.028), but without a significant interaction between these variables (chronic treatment × Tat concentration: F4,81 = 0.025, P = 0.999; Table 1). With high concentrations of Tat, the peak amplitude of evoked spikes gradually decreased in SAL-yoked neurons, and such decreases were much greater in COC-SA neurons (Fig. 4A; SAL-yoked, left column; COC-SA, right column). The lack of significance in the interaction between COC-SA and Tat concentration suggests that these treatments reduced the peak amplitude of evoked action potentials by independent mechanisms.

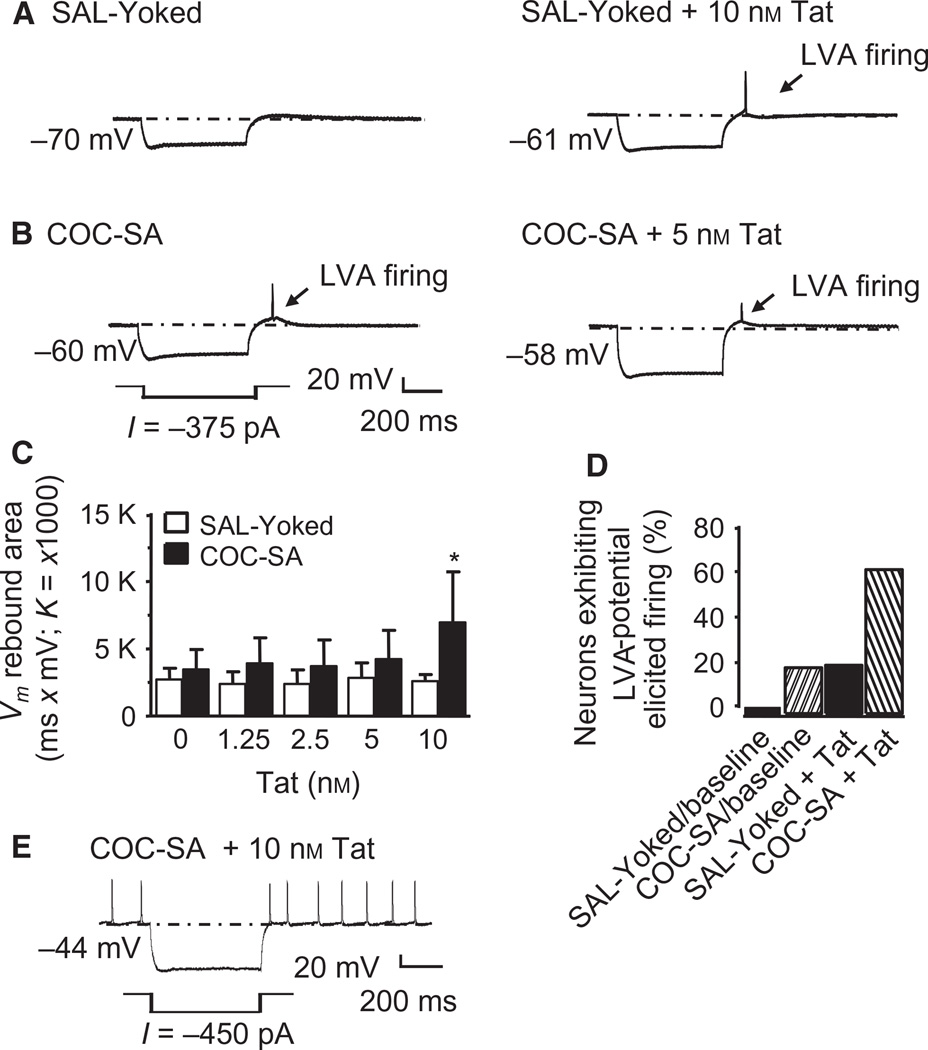

To ascertain the capacity of Tat to alter the subthreshold excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons, negative current pulses (−500 pA to −25 pA) were applied to hyperpolarize the membranes. Marked hyperpolarization can be followed by a subthreshold, low voltage-activated (LVA) potential (Vm rebound), as described previously (Griffith & Matthews, 1986; Khateb et al., 1992; Allen et al., 1993; Napier et al., 2014). Seven of nine neurons recorded from six SAL-yoked rats showed negligible post-hyperpolarization Vm rebound or only a small depolarization (Fig. 5A, left). However, after perfusion with 10 nm Tat, a concentration that depolarized the RMP, the Vm rebound was strikingly evident, being sufficiently large to evoke spontaneous firing in two of nine neurons tested (recorded from two rats; Fig. 5A, right). Three of 14 neurons recorded from three COC-SA rats showed an enlarged LVA potential with spontaneous firing in the absence of Tat (Fig. 5B, left). With the area of the Vm rebound as an index of the LVA potentials, significance was obtained for chronic treatment (F1,81 = 25.875, P < 0.001) and Tat concentration (F4,81 = 2.896, P = 0.026), as well as for the chronic treatment × Tat concentration interaction (F4,81 = 2.780, P = 0.031). Post hoc analysis revealed that the enlarged Vm rebound area of the recorded neurons showing spontaneous firing was significantly increased by 10 nm Tat in COC-SA rats (Fig. 5C). The proportion of neurons showing spontaneous firing was significantly different between COC-SA neurons and SAL-yoked neurons [SAL-yoked, baseline, 0/9 neurons from two rats; SAL-yoked, 10 nm Tat, 2/9; COC-SA, baseline, 3/14 neurons from six rats; COC-SA, 10 nm Tat, 9/14; χ21 = 5.287, P = 0.021; Fig. 5D]. A few COC-SA neurons (2/14 neurons from two rats) exposed to 10 nm Tat showed membrane depolarization that led to spontaneous firing even without the post-hyperpolarization Vm rebound, and the firing was further increased after marked membrane hyperpolarization (Fig. 5E). These results suggest COC-SA potentiates the ability of acute Tat to increase the subthreshold excitability of mPFC pyramidal neurons.

Fig. 5.

Both Tat and COC-SA facilitated the LVA potentials that elicited spontaneous firing. (A) Illustrated traces showing that a hyperpolarizing current pulse (−375pA) did not evoke a small Vm rebound (i.e. the LVA potential) in an mPFC pyramidal neuron from a SAL-yoked rat (SAL-yoked baseline; left trace), but facilitated generation of the LVA potential and spontaneous firing in this neuron with bath perfusion of 10 nm Tat (right trace). The arrow refers to where the evoked LVA potential was not seen in the SAL-yoked baseline condition, but was observed in response to acute Tat exposure, or after COC-SA, or both (see below). (B) The LVA potential and spontaneous firing were also evoked by the hyperpolarizing current pulses in a COC-SA neuron in the absence of Tat (COC-SA baseline; left trace). A more hyperpolarized membrane potential was observed than in the SAL-yoked baseline condition. With perfusion of 5 nm Tat, the membrane potential was driven to an even more hyperpolarized level that was followed by a Vm rebound with a deformed action potential (right trace). (C) The bar graphs show that the Vm rebound area was significantly greater in COC-SA neurons (n = 10; black bars) than in SAL-yoked neurons (n = 8; white bars) after perfusion with 10 nm Tat (two-way anova with post hoc Newman– Keuls test, *P < 0.05). (D) The percentage of neurons that showed the LVA potential and Vm rebound-elicited spontaneous firing at baseline and during exposure to 10 nm Tat was significantly different in COC-SA rats (chisquared test; ; P < 0.05). At baseline, there were three of 14 COC-SA neurons (21.4%; light hashed bar) showing spontaneous firing as compared with SAL-yoked neurons (n = 0/9, 0.0%, white bar). Perfusion of Tat (10 nm) caused a further increase in the percentage of neurons showing such changes (SAL-yoked + Tat, n = 2/9, 22.2%, black bar; COC-SA + Tat, n = 9/14, 64.3%, dark hashed bar). (E) The illustrated trace shows that spontaneous firing occurred in some COC-SA neurons with perfusion of 10 nm Tat (n = 2/14, 14.3%), which had a more depolarized RMP and a further increased firing frequency after the hyperpolarized current pulse. Such a phenomenon was not seen in SAL-yoked neurons in the presence of 10 nm Tat.

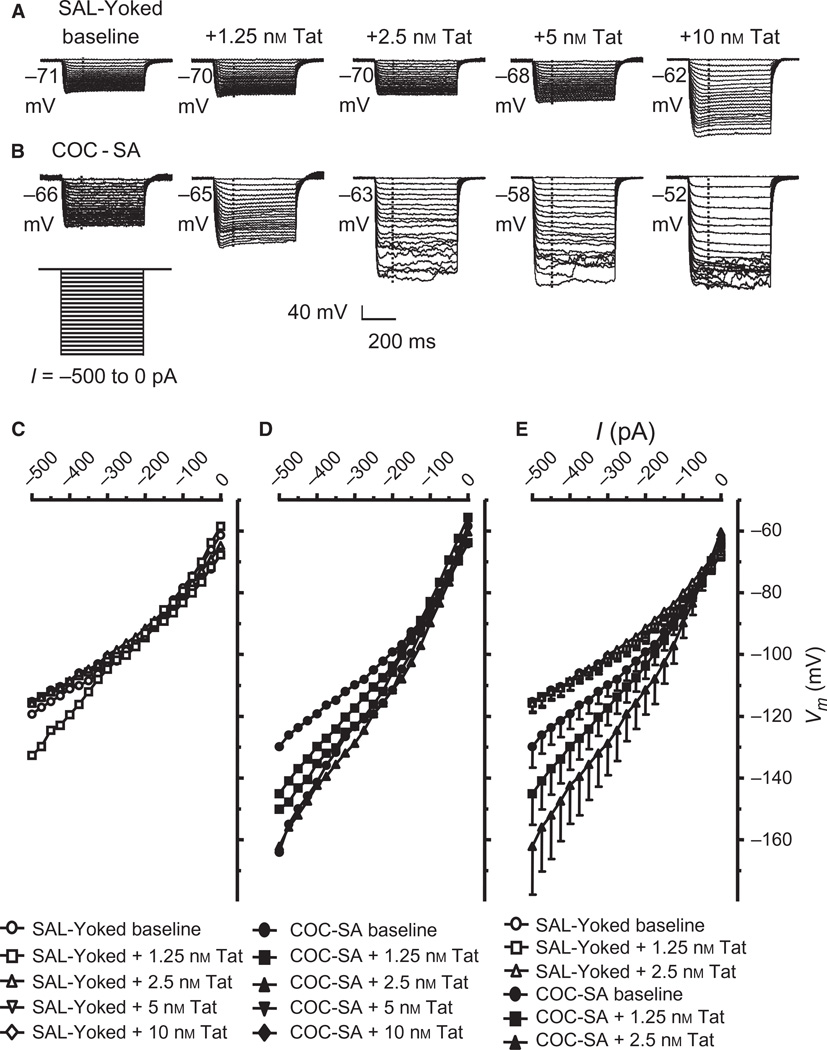

Inward rectification plays an important role in mediating Vm and neuronal responses to neurotransmitters (Bichet et al., 2003). Recording of 14 mPFC neurons from nine COC-SA rats revealed more hyperpolarized Vm levels in response to application of negative current pulses, showing a decrease in the inward rectification as compared with those from SAL-yoked rats (nine neurons from eight rats; SAL-yoked/baseline vs. COC-SA/baseline; Fig. 6). Current–voltage relationships at baseline and at each concentration of Tat are shown for nine neurons from eight SAL-yoked rats (Fig. 6A) and 14 neurons from nine COC-SA rats (Fig. 6B). Inward rectification was significantly reduced across currents in COC-SA neurons (chronic treatment × current: F20,1323 = 6.534, P < 0.001). This reduction was indicated by a much greater downward shift of the hyperpolarized membrane potential (Fig. 6B vs. A). The lower concentrations of Tat (1.25–5 nm) did not alter the inward rectification of SAL-yoked neurons (Fig. 6C), but a higher concentration of Tat (10 nm) induced a similar reduction in the inward rectification as observed with 1.25 nm or 2.5 nm Tat in COC-SA neurons (for example, membrane hyperpolarization reached approximately −160 mV; Fig. 6D). Post hoc analysis revealed that the reduction was significantly greater in COC-SA neurons treated with 1.25 and 2.5 nm Tat than at baseline (Fig. 6E). Together, these results suggest a synergistic effect and then a ceiling effect of cocaine and Tat on reducing the inward rectification in mPFC pyramidal neurons. Because of such effects, the 5 and 10 nm recordings were excluded from the statistical analyses of concentration–response relationships (Fig. 6E). These results suggest that the decreased inward rectification caused by COC-SA and Tat can synergistically alter the ability of mPFC pyramidal neurons to regulate subthreshold membrane excitability.

Fig. 6.

The inward rectification was reduced following COC-SA, and this effect was exacerbated by Tat. (A) Representative traces showing that membrane hyperpolarization by negative current pulses (−500 pA to 0 pA) induced an inward rectification in mPFC pyramidal neurons from SAL-yoked rats in the absence of Tat. Perfusion with 1.25, 2.5 or 5 nm Tat did not alter the inward rectification. The vertical dashed line indicates the time points at which the membrane potentials were measured. (B) COC-SA reduced the inward rectification. Membrane hyperpolarization was enhanced as compared with that in SAL-yoked neurons (left traces). Perfusion with Tat facilitated the reduced inward rectification at all concentrations, driving the membrane potentials to substantially higher hyperpolarization levels. (C) Current–voltage relationships. At baseline, no significant difference in the inward rectification (reflected by a downwards drop of the current–voltage curve) between the neurons from the baseline condition (without Tat) of SAL-yoked rats (n = 9; open circles) and those exposed to 1.25 nm (n = 9; open squares), 2.5 nm (n = 9; open upward triangles), 5 nm (n = 8; open downward triangles) and 10 nm (n = 8; open diamonds) Tat, assessed with a mixed-model anova with post hoc Newman–Keuls test, P < 0.05). (D) Mixed-model anova (with post hoc Newman–Keuls test, P < 0.05) revealed that the inward rectification was significantly reduced in COC-SA neurons in response to bath-applied Tat at 1.25 nm (n = 14; filled squares; P < 0.05), 2.5 nm (n = 14; filled upward triangles; P < 0.05), 5 nm (n = 11; filled downward triangles; P < 0.05) and 10 nm (n = 10; filled diamonds; P < 0.05) as compared with the COC-SA baseline (n = 14; filled circles). Thus, all of the current–voltage curves showed a downward shift in the presence of Tat at different concentrations in COC-SA neurons. (E) As compared with COC-SA neurons at baseline (n = 14; closed circles), bath-applied Tat at 1.25 nm (n = 14; filled squares) and 2.5 nm (n = 14; filled upward triangles) induced a reduction in the inward rectification (post hoc Newman–Keuls test, P < 0.05). This effect was absent in SAL-yoked neurons perfused with bath-applied Tat at 1.25 nm (n = 9; open squares) and 2.5 nm (n = 9; open upward triangles).

The pathophysiology of higher concentrations of Tat

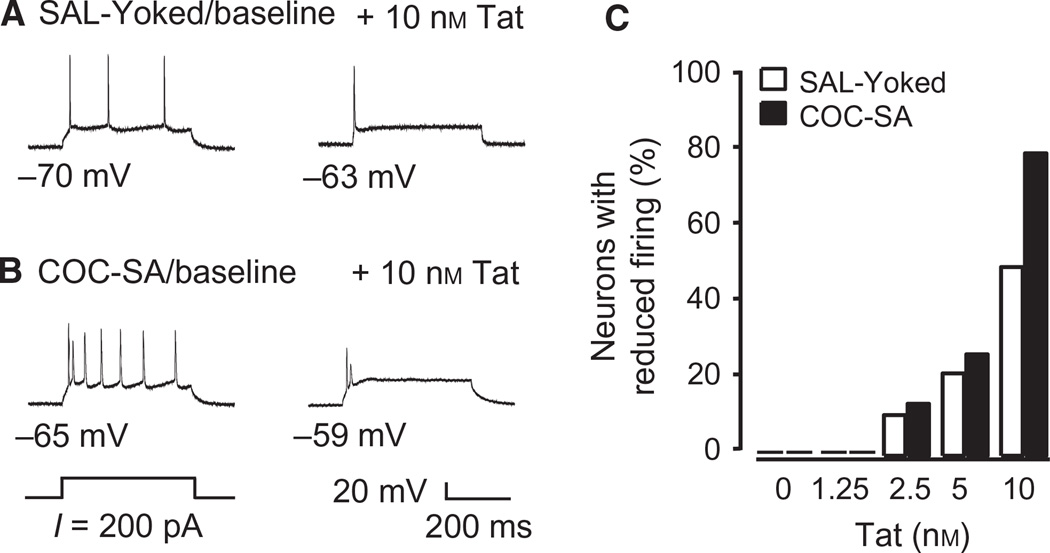

Excessive excitation is detrimental to neurons. This effect can be readily characterised by deformation of the action potential, e.g. a reduction in spike height (Hollerman & Grace, 1989; Hollerman et al., 1992). We noted pathophysiological features of over-activation in our recordings from COC-SA rats with low concentrations of Tat, and that SAL-yoked neurons were devoid of these features during Tat application (Fig. 7A and B). Quantifying this effect, we determined that the number of neurons showing reduced firing frequency and spike amplitude with higher depolarizing currents (300–400 pA) was potentiated by 2.5–10 nm Tat in both SAL-yoked rats (, P = 0.029) and COC-SA rats (, P < 0.001). The highest concentration of Tat studied (10 nm) induced excitotoxicity in eight of 10 recorded neurons from seven COC-SA rats, and in four of eight neurons recorded from seven SAL-yoked rats (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that higher concentrations of Tat rendered mPFC pyramidal neurons more susceptible and vulnerable to over-activation, and that this action was exaggerated in COC-SA rats.

Fig. 7.

A higher concentration of Tat suppressed evoked firing and deformed action potentials in some neurons. (A) Illustrated traces showing that a train of action potentials was evoked by a moderate depolarizing current pulse (200 pA) in an mPFC pyramidal neuron from a SAL-yoked rat in the absence of Tat (SAL-yoked/baseline; left trace). Exposure to 10 nm Tat remarkably suppressed the evoked firing and reduced the spike amplitude (right trace). (B) The same depolarizing current pulse (200 pA) evoked more spikes during the same stimulation period in a COC-SA neuron (COC-SA/ baseline; left trace) than in a SAL-yoked neuron (Fig. 8A, left trace) without Tat exposure. Perfusion with 10 nm Tat also suppressed the evoked firing and deformed the spikes (right trace). (C) Bar graphs indicating that the percentage of neurons that showed such reduced firing and deformed action potentials was significantly increased in both SAL-yoked rats (, P = 0.029) and COC-SA rats (, P < 0.001) in response to bath perfusion of Tat in a concentration-dependent manner. Among these neurons, those from COC-SA rats exposed to 10 nm Tat showed the highest percentage for this decrease.

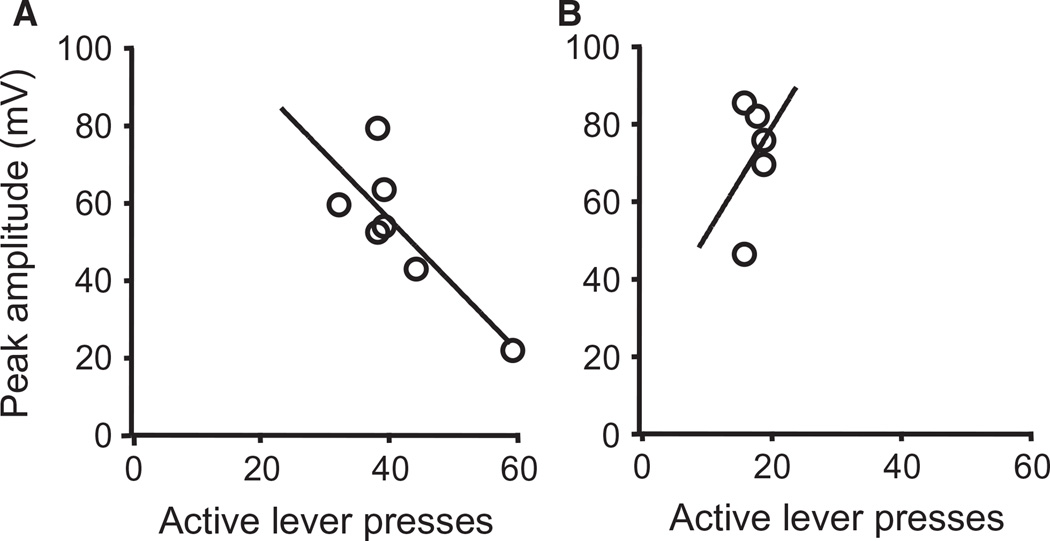

The ability of Tat to reduce spike amplitude correlated with cocaine-seeking in high-responding rats

To determine whether COC-SA-induced drug-seeking was correlated with the altered mPFC neuronal activity, we compared the magnitude of cocaine-seeking in CR2 with Tat-induced changes in evoked firing. There is a wealth of literature showing that outbred Sprague Dawley rats can be grouped into those that show high behavioral responses to cocaine and those that are less sensitive to the stimulant (Sorg et al., 2004; McCutcheon et al., 2009). Accordingly, we grouped the rats into high-responders, i.e. those that showed ≥ 50% enhancement in active lever-pressing between CR1 and CR2, and low-responders, i.e. those that showed < 50% enhancement in active lever-pressing between CR1 and CR2. We tested for correlations between enhanced active lever-pressing during CR2 and the RMP, Rin, rheobase, peak, and after-hyperpolarization. We found that neurons from high-responder COC-SA rats showed a significant reduction in peak amplitude when exposed to a subthreshold concentration of Tat (2.5 nm) (7/12 neurons from nine rats, 58%; correlation analysis, P = 0.0248; Fig. 8A). In contrast, recordings from COC-SA rats, which had < 50% enhancement of active lever-pressing between CR2 and CR1, did not show a correlation with peak amplitude during exposure to 2.5 nm Tat (5/12 neurons from nine rats, 42%; correlation analysis, P > 0.05; Fig. 8B). These correlation results suggest that the Tatinduced alterations in spike amplitude were associated with incubation of cocaine-seeking behavior in this subpopulation of rats and may contribute to over-excitation of neurons exposed to higher concentrations of Tat.

Fig. 8.

Tat-induced reduction of the peak amplitude was correlated with the magnitude of drug-seeking behavior. (A) Correlation analysis revealed a significant reduction in the peak amplitude during exposure to a subthreshold concentration of Tat (2.5 nm) (n = 7/12 neurons from nine rats, 58%; correlation analysis, P < 0.05) in the rats that were high-responders (showing a ≥ 50% enhancement in active lever-pressing during CR2 vs. CR1). (B) Neurons from COC-SA rats, which had a < 50% enhancement of active lever-pressing in drug-seeking behavior during CR2 (over that in CR1), did not have a significantly correlated reduction in the peak amplitude during exposure to 2.5 nm Tat (n = 5/12 neurons from nine rats, 42%; correlation analysis, P > 0.05).

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that drug-seeking behavior in COC-SA rats promoted over-excitation of mPFC pyramidal neurons in response to excitatory stimuli (e.g. depolarizing currents, or the HIV-1 protein Tat). Given the role of the mPFC in regulating cognition and drug-seeking (Grant et al., 1996; McFarland et al., 2003; Peters et al., 2009), these alterations may contribute to the accelerated cognitive deficits and functional/anatomical PFC dysregulation observed in HIV-positive cocaine abusers (Ferris et al., 2008; Meyer et al., 2013).

COC-SA rats showed drug-seeking behavior after forced abstinence (without extinction training) and re-exposure to cocaine-paired cues. The drug-seeking behavior was greater in rats after an 18–21-day withdrawal period than after 1 day of abstinence from the last COC-SA task, which was in agreement with an incubation profile (Grimm et al., 2001; Loweth et al., 2013). The mPFC is organised in a dorsal–ventral pattern, wherein the PrL pyramidal neurons send glutamatergic outputs to the nucleus accumbens core and basolateral amygdala (Heidbreder & Groenewegen, 2003; Peters et al., 2009). Inhibition of these pathways attenuates relapse to cocaine-mediated drug-taking in rats (McFarland et al., 2003; McLaughlin & See, 2003). Together, these findings suggest that COC-SA induces the mPFC neuropathology that renders glutamatergic pyramidal neurons more susceptible and vulnerable to excitatory stimuli. This hyper-responsivity reflected, at least in part, an increase in the suprathreshold excitability evoked by depolarizing currents that generated action potentials. Moreover, they also suggest that such over-excitation alters the PFC glutamate outputs to the subcortical nucleus accumbens and basolateral amygdala, which may contribute to the mechanisms of drug-seeking.

When perfused with 10 nm Tat, the neurons from SAL-yoked rats showed a post-hyperpolarization Vm rebound with spontaneous firing that occurred in the absence of a depolarizing current (subthreshold) and was not seen at baseline. This Vm rebound reflects the subthreshold excitability of pyramidal neurons mediated by LVA-Ca2+ channels that interact with N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (Markram & Sakmann, 1994; Markram et al., 1997). In our prior study using saline-pretreated adolescent rats, we also found such an Vm rebound with spontaneous firing in response to higher concentrations of Tat (40 nm) that was abolished via blocking of the L-channels (Napier et al., 2014). This suggests that the Tat-facilitated Vm rebound and spontaneous firing were probably mediated via enhancement of the activity of the LVA-Ca2+ channels (Khateb et al., 1992). Although it was not directly measured in the current study, enhanced activity of the LVA-Ca2+ channels could increase the activation probability of other voltage-gated ion channels (e.g. Na+ channels and high voltage-activated Ca2+ channels) that control firing. The Vm rebound and associated spontaneous firing were also observed in some neurons from COC-SA rats, and Tat enhanced this effect. When exposed to 10 nm Tat, some neurons even showed spontaneous firing without the Vm rebound. These findings suggest that the combined effects of COC-SA/withdrawal and acute Tat exposure abnormally increase the activity of both LVA and high voltage-activated L-channels, and that both may contribute to mPFC over-excitation.

Tat-induced over-excitation often resulted in a functional pathology identified by a reduced number and amplitude of evoked action potentials. The majority of mPFC pyramidal neurons from SAL-yoked or COC-SA rats were viable for the entire recording duration with lower concentrations of bath-applied Tat (≤ 5 nm). However, only 50% of the neurons from SAL-yoked rats tolerated 10 nm Tat. Neurons from COC-SA rats were even more vulnerable to 10 nm Tat, with 80% of the neurons showing suppressed firing. Given the role of the Na+ channels and L-channels in action potentials and Ca2+ influx, respectively, the Tat-mediated or COC-SA + Tat-mediated inactivation was probably attributable to over-excitation-induced inactivation of Na+ channels and L-channels. Further investigations are required to determine whether such inactivation is mediated by functional or structural alterations in these channels.

Acute Tat exposure and COC-SA decreased the inward rectification in mPFC pyramidal neurons. The exact mechanisms underlying this decrease are unknown. The family of Kir channels (the inward rectifier), including the K2P channels (Braun, 2012), play a critical role in mediating the inward rectification and RMP (Hille, 2001; Bichet et al., 2003), probably via polyamine regulation, which mediates cation currents through these channels. Previous studies have shown that Kir channels are blocked by polyamines (Bichet et al., 2003), and cocaine increases intracellular polyamine levels (Shimosato et al., 1995). The toxic effects of Tat on neurons are also mediated, in part, by direct interactions with polyamine-sensitive sites on N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors (Prendergast et al., 2002). Collectively, these findings suggest that the cocaine/Tat-induced decrease of the inward rectification was mediated by dysfunction of K+ channels, whereby a reduced K+ outflow via Kir and K2P channels could depolarize the RMP. In addition, a decrease in the inflow of K+ and other cationic currents through Kir and Ih channels will result in an accumulation of extracellular K+ and other cations, which would also facilitate membrane depolarization, as observed in the present study.

The present study also determined that the enhanced CR in COC-SA-withdrawn rats was correlated with a reduction in the peak amplitude of action potentials in mPFC pyramidal neurons induced by low concentrations of Tat (2.5 nm). This finding is consistent with an involvement of mPFC dysfunction in drug-seeking. Although the exact mechanism underlying this reduction is unknown, decreased activity of voltage-gated Na+ channels may play a role. Generation of an action potential primarily depends on the activation of voltage-sensitive Na+ channels, and repeated cocaine exposure induces a reduction in whole-cell Na+ currents through these channels, probbaly by altering protein kinase A-mediated signaling (Zhang et al., 1998; Hu et al., 2005; Ford et al., 2009). Thus, this correlation may reflect dysregulation of the Na+ channel in mPFC pyramidal neurons from COC-SA rats, which may contribute to the mechanisms promoting cocaine-seeking in HIV-positive individuals.

We demonstrated in a parallel study that non-contingent administration of cocaine in adolescent rats induced over-activation of L-type channels that was exacerbated by Tat. This increase in the firing of mPFC pyramidal neurons was associated with increased Ca2+ influx via the L-channel on exposure to 40 nm Tat (Napier et al., 2014). In the current study, a similar exacerbation was detected in adult SAL-yoked and COC-SA rats, but to a much greater extent, and the effects occurred with lower concentrations of Tat (5 and 10 nm). Several factors may have contributed to the exaggerated Tat-induced enhancement in excitability seen in the current study during abstinence from cocaine, including differences in age, duration of forced abstinence, and the method of cocaine administration. Age may play a role in the cocaine/Tat-mediated mPFC neuronal over-excitation. Although adolescent and adult rats show comparable intakes of self-administered cocaine (Kerstetter & Kantak, 2007), the consequences of self-administered cocaine differentially affect performance on PFC-mediated tasks (Harvey et al., 2009; Kantak et al., 2014). In addition to age differences, the adolescent rats in our prior study received a large single bolus of experimenter-injected cocaine once daily for 5 days (Napier et al., 2014); in the current study, rats were trained to self-administer (self-titrate) small doses of cocaine over a 2-h operant session for 14 days in the presence of cocaine-paired cues, and such differences may also have contributed to the disparity in neurophysiological consequences. For example, rats that self-administer cocaine and rats that receive cocaine non-contingently are known to have different modulation of glutamate and dopamine transporters in brain regions that include the mPFC (Miguéns et al., 2008). Furthermore, the withdrawal period is known to affect drug-seeking (Loweth et al., 2013). In our previous study, the adolescent rats experienced a 3-day forced abstinence period prior to performance of the recording experiments. In comparison, the present study used an 18–21-day period of forced abstinence prior to performance of the recordings. Both periods of abstinence (3 and 21 days) from repeated cocaine treatment are known to enhance Ca2+ plateau potentials (Nasif et al., 2005a); however, the surface expression of L-type channels is increased only after the protracted withdrawal in cocaine-treated rats (Ford et al., 2009). Together, these findings suggest that all of these factors contribute to the difference in cocaine/Tat sensitivity of these neurons between the two studies.

In the present study, we showed that cocaine-seeking behavior was associated with over-excitation and inactivation of mPFC pyramidal neurons mediated by COC-SA and acute Tat exposure. This finding is relevant because the neurotoxicity of Tat is known to be amplified not only by other viral proteins such as glycoprotein 120 (Haughey & Mattson, 2002), but also by drugs of abuse. Given the fact that the mPFC regulates cognitive function and motivation-driven behavior, our novel findings provide support at the cellular level for reports that the mPFC is altered in cocaine abusers (Goldstein & Volkow, 2011), patients with neuroAIDS (Antinori, 2007), and patients with comorbid diseases (Ferris et al., 2008).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by USPHSGs DA033206, DA033882, the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust, the Chicago Developmental Center for AIDS Research (P30AI082151), and the Center for Compulsive Behavior and Addiction at Rush University Medical Center.

Abbreviations

- COC-SA

cocaine self-administration

- CR

cue-reactivity

- FR1

fixed-ratio 1

- FR5

fixed-ratio 5

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- L-channel

voltage-gated L-type Ca2+ channel

- LVA

low voltage-activated

- mPFC

medial prefrontal cortex

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- PrL

prelimbic subregion of the medial prefrontal cortex

- Rin

input resistance

- rmanova

repeated-measures anova

- RMP

resting membrane potential

- SAL-yoked

saline-yoked

- Tat

transactiva-tor of transcription

References

- Allen TGJ, Sim JA, Brown DA. The whole-cell calcium current in acutely dissociated magnocellular cholinergic basal forebrain neurones of the rat. J. Physiol. (London) 1993;460:91–116. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, Clifford DB, Cinque P, Epstein LG, Goodkin K, Gisslen M, Grant I, Heaton RK, Joseph J, Marder K, Marra CM, McArthur JC, Nunn M, Price RW, Pulliam L, Robertson KR, Sacktor N, Valcour V, Wojna VE. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D, Haass FA, Jan LY. Merging functional studies with structures of inward-rectifier K(+) channels. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003;4:957–967. doi: 10.1038/nrn1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu GC, Brailoiu E, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Excitatory effects of human immunodeficiency virus 1 Tat on cultured rat cerebral cortical neurons. Neuroscience. 2008;151:701–710. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun AP. Two-pore domain potassium channels: variation on a structural theme. Channels. 2012;6:139–140. doi: 10.4161/chan.20973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Samaniego F, Nair BC, Buonaguro L, Ensoli B. HIV-1 Tat protein exits from cells via a leaderless secretory pathway and binds to extracellular matrix-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycans through its basic region. AIDS. 1997;11:1421–1431. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199712000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BT, Yau HJ, Hatch C, Kusumoto-Yoshida I, Cho SL, Hopf FW, Bonci A. Rescuing cocaine-induced prefrontal cortex hypoactivity prevents compulsive cocaine seeking. Nature. 2013;496:359–362. doi: 10.1038/nature12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish JL, Duffy P, Kalivas PW. A role for nucleus accumbens glutamate transmission in the relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1359–1367. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Everall IP, Weich S, McLaughlin J, Scaravilli F, Lantos PL. HIV-associated brain pathology in the United Kingdom: an epidemiological study. AIDS. 1997;11:1145–1150. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris MJ, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Neurotoxic profiles of HIV, psychostimulant drugs of abuse, and their concerted effect on the brain: current status of dopamine system vulnerability in NeuroAIDS. Neurosci. Biobehav. R. 2008;32:883–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KA, Wolf ME, Hu XT. Plasticity of L-type Ca2+ channels after cocaine withdrawal. Synapse. 2009;63:690–697. doi: 10.1002/syn.20651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011;12:652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant S, London ED, Newlin DB, Villemagne VL, Liu X, Contoreggi C, Phillips RL, Kimes AS, Margolin A. Activation of memory circuits during cue-elicited cocaine craving. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:12040–12045. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Napier TC. Mirtazapine alters cue-associated methamphetamine seeking in rats. Biol. Psychiat. 2011;69:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves SM, Napier TC. SB 206553, a putative 5-HT2C inverse agonist, attenuates methamphetamine-seeking in rats. BMC Neurosci. 2012;13:65–74. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-13-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith WH, Matthews RT. Electrophysiology of AChE-positive neurons in basal forebrain slices. Neurosci. Lett. 1986;71:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs R, Weir C, Wayman W, Koeltzow TE. Intermittent methylphenidate during adolescent development produces locomotor hyperactivity and an enhanced response to cocaine compared to continuous treatment in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Be. 2010;96:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Kruzich PJ, See RE. Contingent access to stimuli associated with cocaine self-administration is required for reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. Psychobiology. 2000;28:383–386. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y. Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature. 2001;412:141–142. doi: 10.1038/35084134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey RC, Dembro KA, Rajagopalan K, Mutebi MM, Kantak KM. Effects of self-administered cocaine in adolescent and adult male rats on orbitofrontal cortex-related neurocognitive functioning. Psychopharmacology. 2009;206:61–71. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1579-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey NJ, Mattson MP. Calcium dysregulation and neuronal apoptosis by the HIV-1 proteins Tat and gp120. JAIDS. 2002;31(Suppl 2):S55–S61. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200210012-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Groenewegen HJ. The medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: evidence for a dorso-ventral distinction based upon functional and anatomical characteristics. Neurosci. Biobehav. R. 2003;27:555–579. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heng L, Markham JA, Hu XT, Tseng KY. Concurrent upregulation of postynaptic L-type Ca2+ channel function and protein kinase A signaling is required for the periadolescent facilitation of Ca2+ plateau potentials in the prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:953–962. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. New York: Skyscrape; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Grace AA. Acute haloperidol administration induces depolarization block of nigral dopamine neurons in rats after partial dopamine lesions. Neurosci. Lett. 1989;96:82–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerman JR, Abercrombie ED, Grace AA. Electrophysiological, biochemical, and behavioral studies of acute haloperidol-induced depolarization block of nigral dopamine neurons. Neuroscience. 1992;47:589–601. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X-T, Ford K, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration decreases calcineurin (PP2B) but enhances DARPP-32 modulation of sodium currents in rat nucleus accumbens neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:916–926. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantak KM, Barlow N, Tassin DH, Brisotti MF, Jordan CJ. Performance on a strategy set shifting task in rats following adult or adolescent cocaine exposure. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:4489–4501. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3598-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Kantak KM. Differential effects of self-administered cocaine in adolescent and adult rats on stimulus-reward learning. Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0852-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khateb A, Mühlethaler M, Alonso A, Serafin M, Mainville L, Jones BE. Cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons display the capacity for rhythmic bursting activity mediated by low-threshold calcium spikes. Neuroscience. 1992;51:489–494. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90289-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koya E, Uejima JL, Wihbey KA, Bossert JM, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ventral medial prefrontal cortex in incubation of cocaine craving. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1):177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Huang Y, Reid R, Steiner J, Malpica-Llanos T, Darden TA, Shankar SK, Mahadevan A, Satishchandra P, Nath A. NMDA receptor activation by HIV-Tat protein is clade dependent. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:12190–12198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3019-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loweth JA, Tseng KY, Wolf ME. Adaptations in AMPA receptor transmission in the nucleus accumbens contributing to incubation of cocaine craving. Neuropharmacology. 2013;76B:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Sakmann B. Calcium transients in dendrites of neocortical neurons evoked by single subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potentials via low-voltage-activated calcium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:5207–5211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Lubke J, Frotscher M, Sakmann B. Regulation of synaptic efficacy by coincidence of postsynaptic APs and EPSPs. Science. 1997;275:213–215. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JE, White FJ, Marinelli M. Individual differences in dopamine cell neuroadaptations following cocaine self-administration. Biol. Psychiat. 2009;66:801–803. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Kalivas PW. The circuitry mediating cocaineinduced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:8655–8663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-21-08655.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Prefrontal glutamate release into the core of the nucleus accumbens mediates cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3531–3537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J, See RE. Selective inactivation of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex and the basolateral amygdala attenuates conditioned-cued reinstatement of extinguished cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2003;168:57–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mediouni S, Darque A, Baillat G, Ravaux I, Dhiver C, Tissot-Dupont H, Mokhtari M, Moreau H, Tamalet C, Brunet C, Paul P, Dignat-George F, Stein A, Brouqui P, Spector SA, Campbell GR, Loret EP. Antiretroviral therapy does not block the secretion of the human immunodeficiency virus Tat protein. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2012;12:81–86. doi: 10.2174/187152612798994939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melrose RJ, Tinaz S, Castelo JM, Courtney MG, Stern CE. Compromised fronto-striatal functioning in HIV: an fMRI investigation of semantic event sequencing. Behav. Brain Res. 2008;188:337–347. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer VJ, Rubin LH, Martin E, Weber KM, Cohen MH, Golub ET, Valcour V, Young MA, Crystal H, Anastos K, Aouizerat BE, Milam J, Maki PM. HIV and recent illicit drug use interact to affect verbal memory in women. JAIDS. 2013;63:67–76. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318289565c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguéns M, Crespo JA, Del Olmo N, Higuera-Matas A, Montoya GL, Garcia-Lecumberri C, Ambrosio E. Differential cocaineinduced modulation of glutamate and dopamine transporters after contingent and non-contingent administration. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:771–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napier TC, Chen L, Kashanchi F, Hu XT. Repeated cocaine treatment enhances HIV-1 Tat-induced cortical excitability via over-activation of L-type calcium channels. J. Neuroimmune Pharm. 2014;9:354–368. doi: 10.1007/s11481-014-9524-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasif FJ, Hu XT, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration increases voltage-sensitive calcium currents in response to membrane depolarization in medial prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005a;25:3674–3679. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0010-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasif FJ, Sidiropoulou K, Hu XT, White FJ. Repeated cocaine administration increases membrane excitability of pyramidal neurons in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005b;312:1305–1313. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.075184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Perez MF, White FJ, Hu XT. Dopamine D(2) receptor modulation of K(+) channel activity regulates excitability of nucleus accumbens neurons at different membrane potentials. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2217–2228. doi: 10.1152/jn.00254.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, Kalivas PW, Quirk GJ. Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learn. Memory. 2009;16:279–288. doi: 10.1101/lm.1041309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast MA, Rogers DT, Mulholland PJ, Littleton JM, Wilkins LH, Jr, Self RL, Nath A. Neurotoxic effects of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 transcription factor Tat require function of a polyamine sensitive-site on the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor. Brain Res. 2002;954:300–307. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03360-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimosato K, Watanabe S, Marley RJ, Saito T. Increased polyamine levels and changes in the sensitivity to convulsions during chronic treatment with cocaine in mice. Brain Res. 1995;684:243–247. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00468-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg BA, Li N, Wu W, Bailie TM. Activation of dopamine D1 receptors in the medial prefrontal cortex produces bidirectional effects on cocaine-induced locomotor activity in rats: effects of repeated stress. Neuroscience. 2004;127:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wayman WN, Dodiya HB, Persons AL, Kashanchi F, Kordower JH, Hu X-T, Napier TC. Enduring cortical alterations after a single in vivo treatment of HIV-1 Tat. NeuroReport. 2012;23:825–829. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283578050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Neuveut C, Tiffany HL, Benkirane M, Rich EA, Murphy PM, Jeang KT. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:11466–11471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X-F, Hu X-T, White FJ. Whole-cell plasticity in cocaine withdrawal: reduced sodium currents in nucleus accumbens neurons. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:488–498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00488.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]