Abstract

The present study investigated the role of low academic competence in the emergence of depressive cognitions and symptoms. Structural equation modeling was conducted on a longitudinal sample of African American boys (n = 253) and girls (n = 221). Results supported the hypothesized path models from academic competence in 1st grade to depressive symptoms in 7th grade, controlling for a host of correlated constructs (conduct problems, inattention, social problems). Perceived control in 6th grade mediated the effect of academic competence on depressive symptoms. Although the models fit the data well for both boys and girls, the path coefficients were notably larger for girls; in particular, multiple-group analysis revealed a statistically stronger effect of low academic competence on perceptions of control for girls. The study and findings fit well with counseling psychologists’ commitment to prevention activities and to culture-specific research. Implications for designing interventions and prevention strategies for children with early academic problems are discussed.

Keywords: academic competence, depression, control-related beliefs, African Americans

Given the robust literature on the relationship between negative cognitions and depression, it is surprising how little was known until recently about when and how these cognitions emerge (McGinn, Cukor, & Sanderson, 2005). Explicating the development of negative cognitions has important implications for the design of prevention and treatment strategies. For instance, evidence that negative cognitions emerge from early parent modeling would direct prevention efforts to focus on minimizing these parenting influences. Additionally, specifying the timing of cognitive influence over depressive symptoms could help guide clinicians to make decisions about when cognitive methods are needed to supplement behavioral interventions for depressed children.

Growing evidence supports the role of social variables in explaining the development of depressive cognitions such as control-related beliefs. Research has shown that parenting behaviors marked by control, intrusiveness, inconsistency, and overprotection may compromise children’s control-related beliefs (Carton & Nowicki, 1994; Cole & Rehm, 1986; McGinn et al., 2005; Rudolph, KurlakowsKy, & Conley, 2001; Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, J. P., 1998). In addition to the home environment, school is a social setting that provides children with many opportunities to learn contingencies between actions and outcomes (Skinner et al., 1998). Similar to the findings regarding parenting, research has shown that classroom organization and interactions stimulate beliefs about competence and self-control. Structured and supportive school environments encourage mastery beliefs, whereas unpredictable classrooms contribute to negative self-perceptions (Eccles et al., 1991; Rudolph et al., 2001; Skinner et al., 1998). Failure feedback may be particularly damaging to children’s emerging perceptions of control (Rudolph et al., 2001).

Learning problems serve as an independent risk factor for depression, at least through middle childhood (Herman, Lambert, Ialongo, & Ostrander, 2007; Kellam, Brown, Rubin, & Ensminger, 1983). Kellam and colleagues (1983) found that early learning problems predicted later distress, including depressive symptoms in boys (Kellam et al., 1983), and an intervention that reduced academic risk also lowered subsequent depressive symptoms (Kellam, Rebok, Mayer, Ialongo, & Kalodner, 1994). More recently, analysis of longitudinal data from the Pittsburgh Youth Study (Maughan, Rowe, Loeber, & Stouthamer-Loeber, 2003) showed that reading problems occurred before the emergence of depressive symptoms for children aged 7–10 years. Severe reading problems increased risk of depression threefold for boys in this middle-childhood group from baseline assessment to 6-month follow-up. The predictive value of reading problems remained strong even when controlling for family variables, conduct problems, and inattention. However, available research does not support the reverse path between depression and learning problems (Anderson, Williams, McGee, & Silva, 1989; Maughan et al., 2003).

Given the demonstrated relationship between academic problems and depressive symptoms, a tenable hypothesis is that low academic competence fosters control-related beliefs associated with depression. In other words, school failure and dissatisfaction, which lead to depressive symptoms in younger children, may also contribute to the development of stable beliefs about their perceived efficacy to influence school-related outcomes. As cognitions begin to stabilize around the age of 9 or 10 (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Fincham & Cain, 1986; Herman & Ostrander, 2007; Nicholls & Miller, 1984), negative perceptions of personal control may mediate the academic competence–depression relationship.

Consistent with this hypothesis, Cole, Jacquez, and Maschman (2000) refined traditional cognitive theories of adult depression and proposed a competency-based model to describe the emergence of depressive symptoms in children. Similar to the traditional models, self-perceptions of competence contribute to depressive symptoms in the competency framework. However, according to Cole et al., these self-perceptions are learned from others’ perceptions and represent accurate appraisals of academic and social competence in early childhood. In other words, real performance deficits may precede self-perceptions of incompetence that are linked to depressive symptoms. In line with the looking glass hypothesis, Cole et al. proposed that peers and teachers accurately perceive a child’s incompetence in two critical domains, academic and social skills, and communicate these perceptions to the child who comes to view himself or herself as incompetent. In later childhood and early adolescence, these self-perceptions provide fertile ground for cognitive distortions that are associated with depressive symptoms in adults. Cross-sectional and longitudinal research supports Cole’s competency model of depression (Cole, Jacquez, & Maschman, 2001; Cole, Martin, Powers, & Truglio, 1996; Cole & Turner, 1993).

In particular, Herman and colleagues have documented the role of low academic competence in contributing to depressive symptoms in children. In two distinct samples, they found that academic problems mediated the known relationship between inattention and depression even when controlling for conduct problems (Herman et al., 2007; Herman & Ostrander, 2007; Ostrander & Herman, 2006). Their results suggest that one reason that children with attention problems are at greater risk for developing depression is because inattention undermines their academic skills. In a cross-sectional study, they also found that academic deficits contributed to the emergence of depressogenic cognitions.

Several recent investigations have explored the role of race and ethnicity in young children’s depressive symptoms. Cole and colleagues reported depressive symptoms were more common among African American children compared with Euro-American children (Cole, Martin, Peeke, Henderson, & Harwell, 1998), but in general, the competency model of depression has fit well across different racial and ethnic groups. In subsequent studies, Kistner and her colleagues (Kistner, David, & White, 2003; Kistner, David-Ferdon, Lewis, & Dunkin, 2007) found the highest rates of depression among African American boys and that achievement deficits consistently predicted future risk for depression across racial and ethnic groups.

Gender differences in academic self-perceptions may emerge during early and middle childhood as well. Boys tend to have higher expectations and be more optimistic about their academic potential (Frey & Ruble, 1987), whereas girls tend to underestimate their academic competence (Frome & Eccles, 1995). Girls are also more apt to adopt attributional biases by focusing on their low ability in explaining failure experiences (Frey & Ruble, 1987). Additionally, some studies have found the link between academic difficulties and depressive symptoms was restricted to girls (Willcutt & Pennington, 2000). Given the potential for gender differences to emerge on studied variables, we conducted analyses separately for boys and girls.

Because we were concerned with the unique relationships among early academic problems and future depressive cognitions and symptoms, we also controlled for known correlates of these variables—attention problems, conduct problems, and social problems. Theories and prior research suggest that the externalizing disorders, academic problems, and depression co-occur at rates greater than chance (Hinshaw, 1992; Patterson, Dishion, & Chamberlain, 1993). Including these variables in a model provided a robust test of any observed relationship between academic competence and depressive symptoms.

In summary, theory and empirical data give reason to suspect low academic competence as a risk factor for depressive cognitions, which ultimately lead to depressive symptoms. We build on prior literature in the present study by exploring these relationships among a group of African American children living in an urban context, a population on which academic competence–depression mechanisms have not been tested. Additionally, prior studies have not considered the role of gender differences, inattention, social problems, or conduct problems in modifying the relationship between academic problems and depressive symptoms.

We investigated the relationship between low academic competence and depressive cognitions and symptoms for African American children. We conducted analyses separately for boys and girls and controlled for baseline conduct problems, inattention, and social problems. We hypothesized that perceived control would mediate the relationship between low academic competence and depressive symptoms for boys and girls when controlling for these baseline characteristics. Given evidence that girls may be more susceptible to internalize academic failure, we expected the mediating role of perceived control to be especially strong for them.

Method

Participants

Data were drawn from a longitudinal study conducted by the Prevention Intervention Research Center (PIRC) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). The original study population consisted of a total of 678 children and families, representative of students entering first grade in nine Baltimore City public elementary schools. The children were recruited for participation in two school-based, preventive, intervention trials targeting early learning and aggression (Ialongo, Poduska, Werthamer, & Kellam, 2001). Three first-grade classrooms in each of the nine elementary schools were randomly assigned to one of the two intervention conditions or a control condition. The interventions were provided over the first-grade year, following a pretest assessment in the early fall.

Six hundred sixty-one children participated in the intervention trial in the fall of 1993 and completed self-reports of depressive symptoms on at least one assessment occasion in Grades 1–3. Eighty-nine percent (n = 585) of these children were African American. Analyses for this study focused on African American boys (n = 253) and girls (n = 221) who enrolled in the study in first grade and who completed assessments during the spring of seventh grade. African American children who completed seventh-grade assessments did not significantly differ from the African American children who did not on measures of self-reported depression, teacher-rated attention problems, or academic achievement scores collected during the fall of first grade ( ps > .05). As an indicator of low socioeconomic status, 71.1% of the sample for the present study received free lunch or reduced lunches according to parent report in the fall of first grade. This percentage did not significantly differ for those who completed seventh-grade assessments and those who did not ( ps > .05).

Assessment Procedures

Written informed consent was obtained from parents and verbal assent from the youth. Data for this study were obtained in the fall of first grade, the spring of sixth grade, and the spring of seventh grade. The predictors (low academic competence) and covariates (depressive symptoms, conduct problems, attention problems, social problems, and intervention status) were assessed in fall of Grade 1. The mediator (perceived control) was assessed in spring of Grade 6. The outcome variable (depressive symptoms) was assessed in spring of Grade 7. The time lag between measurement of the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables for this study was selected in order to permit conclusions about the influence of academic problems on subsequent perceived control and depressive symptoms. Measures of perceived control were not gathered in this study prior to sixth grade.

Instruments

Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaptation-Revised (TOCA-R; Werthamer-Larsson, Kellam, & Wheeler, 1991)

Teacher ratings of attention problems and conduct problems were obtained in the fall semester of the first grade using the TOCA-R (Werthamer-Larsson et al., 1991). The TOCA-R was developed and used by the JHU PIRC in the evaluation of the first- and second-generation JHU PIRC trials. The TOCA-R requires teachers to respond to 43 items pertaining to the child’s adaptation to classroom task demands over the last 3 weeks. Adaptation is rated by teachers on a 6-point frequency scale (ranging from 1 [almost never] to 6 [almost always]). Items for the subscales were largely drawn from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.; DSM–III; 3rd ed., rev.; DSM–III–R; 4th ed., text rev.; DSM–-IV–TR; American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1987, 2000).

The Attention-Concentration Problems subscale has nine items (e.g., “pays attention,” “easily distracted”) and a reported alpha of .91 in fall and spring of first grade. In terms of concurrent validity, each single unit of increase in teacher-rated attention/concentration problems was associated with a twofold increase in risk of teacher perception of the need for medication for such problems. In addition, for each unit increase in TOCA-R Attention/Concentration subscale scores in Grade 1, there was just under a 60% increase in the likelihood of failing to graduate from high school. Although diagnoses were not used in the present study, teacher ratings of inattention are considered the gold standard for identifying children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Ostrander, Weinfurt, Yarnold, & August, 1998). Inattention is normally distributed in the general population, and diagnostic classifications are used more for convenience.

The Conduct Problems subscale, measuring aggressive/disruptive behaviors, has nine items, including the following: started physical fights with classmates, lied, took other’s property, and coerced classmates. The coefficient alpha for the Conduct Problems subscale during first grade was .94. The 6-month test–retest intraclass reliability coefficient was .50. Scores on the Conduct Problems subscale have been shown to significantly relate to the incidence of school suspensions (i.e., the higher the score on conduct problems, the greater the likelihood of being suspended from school that year).

Depressed mood

The Baltimore How I Feel-Young Child Version, Child Report (BHIF-YC-C; Ialongo et al., 1999a) is a child self-report scale of depressive and anxious symptoms; items from the Depression subscale for the analyses described below were used. The BHIF-YC-C was designed to be used as a first-stage measure in two-stage epidemiologic investigations of the prevalence of child mood and anxiety disorders, as defined in the DSM–III–R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987); therefore, BHIF-YC-C items map onto DSM–III–R criteria for major depression and overanxious and separation anxiety disorders. A pool of items was drawn from existing child self-report measures, including the Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992), the Depression Self-Rating Scale (Asarnow & Carlson, 1985), the Hopelessness Scale for Children (Kazdin, Rodgers, & Colbus57, 1986), and the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1979).

The BHIF-YC-C was designed to be administered on a classroom-wide basis and to require no reading skills on the part of the children. It is administered by a three-person team made up of adult lay interviewers. While one team member reads each item aloud twice to the class, the two other team members circulate through the classroom maintaining classroom order and assisting children who are having difficulties in paying attention or understanding the instructions. To further obviate the need for reading skills, pictures of common objects (e.g., a ball, apple, and so forth) are used to represent the items and the answer choices in the booklets the children use to record their responses. For each item, children report the frequency of depressive and anxious symptoms over the last 2 weeks on a 3-point scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = almost always). The typical administration time is approximately 30–35 min.

Two BHIF-YC-C time points were used for the present analyses: fall of first grade and spring of seventh grade. The internal consistency for the BHIF-YC-C 14-item Depression subscale was .70 in first grade and .75 in third grade. Two-week test–retest reliability coefficients have ranged from .60 in first grade to .70 in middle school (Ialongo et al., 1999a). The 6-month, test–retest correlation coefficient in first grade for the BHIF-YC-C Depression subscale was .31, reasonable stability given the fluctuating nature of the construct. In terms of concurrent validity, for each standard deviation increase in BHIF-YC-C Depression subscale scores in first grade, there was a threefold and statistically significant increase in the likelihood of the child’s parent reporting that the child was in need of mental health services for “feeling sad, worried, or upset.” Data from the first-generation PIRC data sets revealed that child self-reports on the BHIF-YC-C Depression subscale during elementary school predicted to an age 19–20 report of a lifetime suicide attempt (odds ratio [OR] = 2.38, confidence interval [CI]= 1.30, 4.25) and a diagnosis of a lifetime episode of major depressive disorder (OR = 1.84, CI = 1.16, 2.92). More generally, the prognostic power of young children’s self-reported depressive symptoms was demonstrated by Ialongo, Edelsohn, and Kellam (2001). In a sample of mostly African American children from low-income families in Baltimore, Ialongo et al. found that first-grade self-reports of depressive symptoms predicted future need for and use of mental health services, future suicidal ideation, and diagnosis of major depressive disorder at age 14. Adolescent reports on the BHIF-YC-C in middle school are significantly associated with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children IV (Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000).

Academic competence (Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills; CTBS)

The Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills 4 (CTBS, 1990). The CTBS represents one of the most frequently used standardized achievement batteries in the United States. Subtests on the CTBS cover both verbal (word analysis, visual recognition, vocabulary, comprehension, spelling, and language mechanics and expression) and quantitative topics (computation, concepts, and applications). The CTBS was standardized on a nationally representative sample of 323,000 children from kindergarten through Grade 12. In the present study, the CTBS was administered during the fall of first grade. The CTBS total math and reading scores for each child collected during the fall of first grade were used for all analyses.

Peer relations

The Social Preference Construct is a subscale of the Pupil Nomination Inventory (PNI; Ialongo et al., 1999b). The PNI is a modified version of the Pupil Evaluation Inventory (PEI; Pekarik, Prinz, Leibert, Weintraub, & Neale, 1976). Ten items were selected from the original PEI on the basis of their relevance to three constructs: authority acceptance/aggressive behavior, social participation/shy behavior, and likeability/rejection. An additional four items were added to tap psychological well-being. The assessment was administered by providing pictures of each of the children in the classroom along with their names. The pictures were taken with a digital camera, uploaded to a personal computer, and then printed on an optical scan sheet for each question/nomination item. The scan sheet contained a bubble for each picture. The items were read aloud to the class, and each child filled in the bubble under the picture of a classmate if that classmate fit the description included in the question/nomination item (e.g., “Which children do you like best?”). Children were able to make unlimited nominations of classmates for each question. The raw scores on each of the above dimensions were converted to standard scores on the basis of the distribution of nominations within a child’s classroom. The social preference construct was determined by calculating the mean percent nomination for likeability versus the mean percent nomination for rejection for fall of first grade, with lower scores indicating that the child is less preferred and rejected more by classroom peers.

Test–retest correlations (intraclass correlation coefficients [ICC]) over a 6-month interval ranged from .19 to .66 for the 14-item peer nomination items. The test–retest data for the social preference construct were as follows: “Which children are your best friends?” (ICC = .55), “Which children don’t you like?” (ICC = .52). In terms of concurrent validity, the peer nomination items “Which children are your best friends” and “Which children do you like best” were each correlated in the expected direction with teacher-rated likeability/rejection in first grade (“best friends,” r = −.11; “like best”, r = −.18) for boys. The correlations were modest in magnitude but statistically significant. For girls, the correlation between “best friends” and teacher-rated likeability/rejection was significant and in the expected direction (r = −.30). The correlation between teacher-rated likeability/rejection and “like best” was also significant (r = −.32).

Perceived control

Perceived control was assessed using the Control scale developed by Weisz and colleagues (Weisz, Southam-Gerow, & McCarty, 2001; Weisz, Southam-Gerow, & Sweeney, 1998; Weisz, Sweeney, Proffitt, & Carr, 1993). The Control scale assesses beliefs about one’s ability to exert control over outcomes in academic, social, and behavioral domains. It has demonstrated relationships with depressive symptoms and low-perceived personal competence, another type of control-related belief, and also with perceived noncontingency of outcomes. Children respond to each item using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very true). Weisz et al. (2001) reported an alpha of .88 for total control scores. For the present study, academic and social perceived control scores were calculated by summing items in each of these domains. Total scores on the Academic and Social Perceived Control subscales were used as indicators of the perceived control latent construct, given that the competency model of depression holds that self-perceptions of both social and academic competence play a central role in the development of depression (Cole, Jacquez, & Maschman, 2001).

Perceptions of control were not collected prior to the fall of 6th grade in this sample; thus, the first measurement time point was used in the analyses described below. Although earlier assessments of perceived control would have been optimal, sixth grade is a critical period in the development of perceptions of control. As noted in the introduction, prior research has indicated that these cognitions only begin to stabilize around the age of 9 or 10 and take on a mediating role around that time (see Herman & Ostrander, 2007). Additionally, sixth grade was the first year of middle school for children in the present study, which is another key transition point (after school entry) for understanding developmental psychopathology according to the life course perspective that guided this research.

Analytic Plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM)

SEM was used to examine the hypothesized relationships among the latent constructs and to examine the relations between the predictors, mediators, and outcome variables. SEM was conducted using Mplus 4.2 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004), and maximum likelihood estimates were obtained. Bootstrapping methods with 500 draws were used with all SEM analyses to obtain less biased estimates of standard errors. The Mplus software uses a full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption that the data are missing at random (MAR; Arbuckle, 1996; Little, 1995), which is a widely accepted way of handling missing data (Muthén & Shedden, 1999). The minimum covariance coverage recommended for reliable model convergence is .10 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004). In this study, coverage ranged from .83 to 1.00.

Our measurement model balanced our desire to have two, or if possible three, indicators per variable while limiting the number of parameters estimated so as not to exceed conventional parameter to subject ratios. To provide more than one indicator of Time 3 depressive symptoms and allow the analyses to consider measurement error for this construct, a latent variable was created in the measurement model by dividing the scale into three separate item parcels. Item parcels are often used and preferred over individual items in SEM analyses because they are more likely to meet assumptions of the maximum likelihood procedures used in SEM, provide more precise estimates of parameters, and simplify models by reducing the number of parameters (Nasser & Wisenbaker, 2003).

Structural model fit was evaluated using multiple indicators of fit: chi-square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested that CFI and TLI values above .95 and RMSEA values less than .08 represent acceptable fit; RMSEA values equal to or less than .05 represent good fit (Browne & Cudek, 1993).

Mediated effects were tested according to guidelines outlined by Holmbeck (1997) and MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002). First, the direct effect of the predictor (academic competence) on the outcome (depressive symptoms) was assessed. Next, the fit of a model with paths from the predictor to the mediator (perceived control) and from the mediator to the outcome was tested. Next, models were compared under two conditions: (a) with the path from the predictor to the outcome constrained to zero (Model 1) and (b) with no constraint on the path from the predictor to the outcome (Model 2). A mediated effect is suspected if the addition of the direct path (Model 2) does not improve the fit of Model 1. As a final step, the significance of the indirect effect from the predictor to the outcome was tested using the delta method (see MacKinnon et al., 2002). A significant indirect effect was taken as evidence of mediation.

After testing the models for the overall sample, models were tested separately for boys and girls, consistent with prior literature that suggested that the studied relationships may vary by gender. Intervention status, depressive symptoms, attention problems, peer relations, and conduct problems in Grade 1 were controlled in all models.

Multiple-group analysis

Multiple-group analysis was used to test for gender differences on any identified mediated pathways. The multiple-groups approach is preferable to simply treating gender as a covariate in the models, which would impose many equalities between genders that may not be valid (e.g., within-group variability, residual variances, and effects of covariates). For the multiple-group analysis, the separate SEM models for girls and boys were run to determine whether significant mediation was found for each. Then, a fully constrained model with all paths for boys and girls constrained to be equal versus a model with one path freely estimated for girls was compared. A significant change in chi-square model fit between these models was taken as evidence of gender differences on the path that was freely estimated.

Results

Analyses

Descriptive statistics

We calculated descriptive statistics and preliminary Pearson correlation analyses to determine the univariate relations among study variables (see Tables 1–3). The means and range of scores were similar to prior studies in which these scales with this population were used (Kellam et al., 1994). Of note, the achievement scores on the CTBS were below average (Math M = 435.34; Reading M = 451.81; CTBS normative M = 500) and had less variability than the normative sample (SDs = 88.81 and 65.33 compared with the normative 100). Additionally, the mean depression score in first grade was comparable to scores reported in seventh grade. Although depression rates generally increase over childhood, this finding is consistent with prior studies in which relatively higher rates of depressive symptoms for African American children during childhood were shown (Cole et al., 1998).

Table 1.

Mean Scores on Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attention problems Grade 1 (TOCA-R) | 2.89 | 1.36 | 1–6 |

| Conduct problems Grade 1 (TOCA-R) | 1.40 | 0.70 | 1–5 |

| Depression Grade 1 (BHIF) | 0.83 | 0.34 | 0–2 |

| Peer relations Grade 1 (PNI) | 0.06 | 0.23 | −0.59–0.86 |

| Math Grade 1 (CTBS) | 434.93 | 90.01 | 201–678 |

| Reading Grade 1 (CTBS) | 451.62 | 66.68 | 229–632 |

| Academic control beliefs Grade 6 | 2.68 | 0.41 | 1–3 |

| Social control beliefs Grade 6 | 2.18 | 0.57 | 1–3 |

| Depression Grade 7 (BHIF) | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0–2 |

Note. TOCA = Teacher Observation of Classroom Adaption-Revised; BHIF = Baltimore How I Feel scale; PNI = Pupil Nomination Inventory; CTBS = Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills.

Table 3.

Intercorrelations Among Study Variables for Males and Females

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Math | — | .67* | −.13 | −.15* | −.47* | .35* | .19* | .30* | .28* | −.06 |

| 2. T1 Reading | .70* | — | −.09 | −.16* | −.47* | .38* | .22* | .29* | −.31* | −.05 |

| 3. T1 Depression | −.05 | −.04 | — | .05 | .08 | −.21* | −.22* | −.21* | .17* | .09 |

| 4. T1 Conduct problems | −.20* | −.20* | .08 | — | .39* | −.28* | .09 | .02 | .01 | .10 |

| 5. T1 Attention problems | −.54* | −.50* | .10 | .50* | — | −.45* | −.03 | −.18* | .10 | .19* |

| 6. T1 Peer relations | .23* | .19 | −.03 | −.37* | −.46 | — | −.06 | .15* | −.07 | −.12 |

| 7. T2 Academic perceived control | .11 | .11 | −.09 | .00 | −.11 | .15 | — | .39* | −.37* | .10 |

| 8. T2 Social perceived control | .08 | .04 | −.09 | −.08 | −.11 | .10 | .39* | — | −.28* | .03 |

| 9. T3 Depression | −.10 | −.05 | −.04 | .09 | .06 | −.08 | −.25* | −.25* | — | −.08 |

| 10. Intervention status | −.03 | .01 | −.05 | .07 | .15* | .03 | .00 | .03 | .03 | — |

Note. Male n = 253. Female n = 221. Intercorrelations for girls appear above the diagonal. Intercorrelations for boys appear below diagonal. T1 = first grade, T2 = sixth grade, T3 = seventh grade

p < .05.

All correlations between key study constructs were significant. Reading achievement was highly correlated with math achievement in first grade (r = .69), and social and academic perceived control were moderately related in sixth grade (r = .39). In addition to the theoretical model used to guide our SEM, these data provided justification for creating separate constructs (Achievement and Perceived Control) in the mediation analyses described below.

Mediation analysis: Overall group

The first two steps of mediation analyses described above were conducted next. Academic competence at Time 1 had a significant direct negative effect on depressive symptoms (B = −.36; p = .0001) at Time 3 when controlling for Time 1 depression, conduct problems, inattention, social problems, and intervention status (Step 1). Additionally, Time 1 academic competence had a direct effect on Time 2 perceived control (B = .35; p = .0001), which, in turn, had a direct negative effect on Time 3 depressive symptoms (B = −.58; p = .0001) (Step 2). Thus, the overall model met Holmbeck’s (1997) first two criteria for a significant mediation effect. The final criterion requires a direct comparison between the full model with the direct path from academic competence to depression constrained to zero (constrained model) and the full model with this path freely estimated (freely estimated model) (see Table 4). The constrained model (Model 1) yielded an adequate fit to the data, χ2(37, N = 474) = 49.22, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .026 (CI = .00, .04). Academic competence had a significant direct effect on perceived control (B = .36; p = .0001), perceived control had a significant direct effect on depressive symptoms (B = −.56; p = .0001). We tested the freely estimated model (Model 2) next. It also yielded an adequate fit to the data, though all fit indices were identical to or lower than the fit for Model 1, χ2(36, N = 474) = 45.77, CFI = .99, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .020(.00–.04). Perceived control had a significant effect on T3 depression (B = −.50; p = .0001) in this model; academic competence did not (B = −.15; p = .05) (i.e., the significant direct effect of academic competence on depression found in Step 1 was reduced to non-significance with perceived control in the model). Next, we compared the chi-square difference between Model 1 and Model 2. The freely estimated model did not significantly improve the model fit over the constrained model, χ2(1, N = 474) = 3.45, p = .063, suggesting that a direct path between academic competence and depressive symptoms was not needed. We used the Delta method to formally test the indirect effect of perceived control on the academic competence–depression relationship. The total indirect effect (−.20) was significant ( p = .0001), providing further evidence of a mediated model for the overall sample.

Table 4.

Goodness-of-Fit Indices for Mediation Models

| Model | χ2(df) | CFI/TLI | RMSEA (90% CI) | χ2 (df) difference: Model 1 vs. Model 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| Mediated model, direct path constrained to 0 | 49.22(37) | .99/.99 | .026 (.00, .04) | |

| Model 2 | ||||

| Nonmediated model, direct path freely estimated | 45.77(36) | .99/.99 | .020 (.00, .04) | 3.45(1), p > .05 |

Note. N = 474. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

Gender-specific models

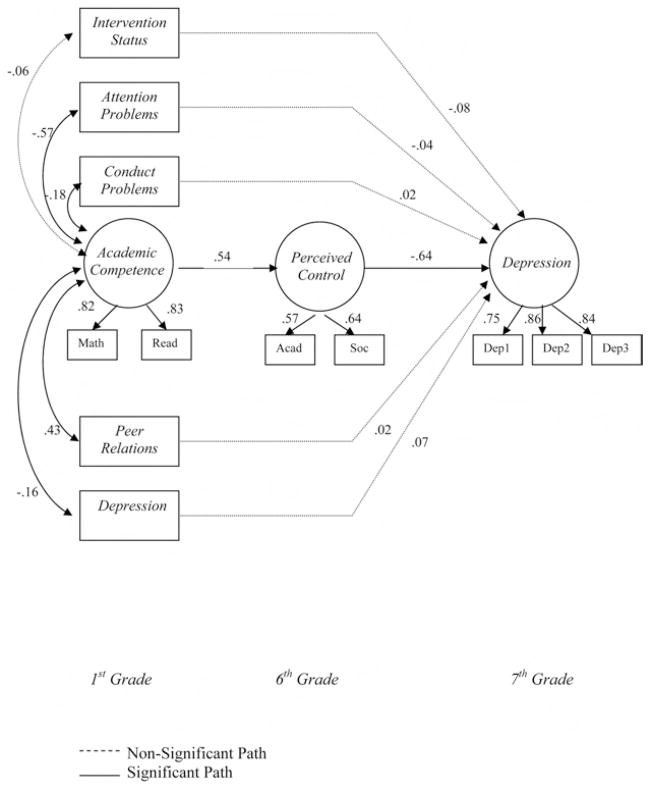

We repeated the above analyses separately by gender to determine whether the paths varied for boys and girls. For girls, the constrained model (Model 1) yielded an adequate fit to the data, χ2(37, N = 221) = 57.18, CFI = .97, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .050(.02–.07). Perceived control had a significant direct effect on depressive symptoms (B = −.64; p = .002). We tested the freely estimated model (Model 2) next. It also yielded an adequate fit to the data, though all fit indices were identical to or lower than the fit for Model 1, χ2(36, N = 221) = 54.22, CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .048(.02–.07). The freely estimated model did not significantly improve the model fit over the constrained model, χ2(1, N = 221) = 2.96, p = .09, suggesting that a direct path between academic competence and depressive symptoms was not needed. Finally, the total indirect effect (−.34) of academic competence on depression was statistically significant ( p = .0015), providing further evidence of a mediated effect for girls.

For boys, the constrained model (Model 1) yielded an adequate fit to the data, χ2(37, N = 253) = 31.02, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = .000(.00 –.03). Perceived control had a significant direct effect on Time 3 depressive symptoms (B = −.45; p = .003) in this model. We tested the freely estimated model (Model 2) next. It yielded a comparable fit for the data, as indicated by nearly all fit indices, χ2(36, N = 253) = 30.69, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0, RMSEA = .000(.00 –.035). As with the analysis for girls, the freely estimated model did not significantly improve the model fit over the constrained model, χ2(1, N = 253) = .33, p = .56, suggesting that a direct path between academic competence and depressive symptoms was not needed. The total indirect effect (.09) of academic competence on depression was significant ( p = .047). Thus, the mediated model (Model 1) was accepted as the best fitting model for boys. Final path coefficients were derived from final betas in each of the above structural models. These coefficients are depicted in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Final structural model from inattention to depression for girls. Read = Reading; Acad = Academic; Soc = Social; Dep = Depression.

Figure 2.

Final structural model from inattention to fepression for boys. Read = Reading; Acad = Academic; Soc = Social; Dep = Depression.

Multiple-group analysis

We conducted multiple-group analysis to determine whether these visually different path models for boys and girls were statistically different. In multiple-group analysis, we first compared the fully constrained model (i.e., with all paths set as equal for boys and girls) with a model with the path from academic problems (A) to perceived control (B) freely estimated for girls. The model fit for the fully constrained model, χ2(84, N = 474) = 117.98, was significantly worse than the model with the academic competence→perceived control path freely estimated, χ2(83, N = 474) = 111.48. The two models were significantly different, χ2(1, N = 474) = 6.48, p = .01, suggesting that there were gender differences on this path. The notably large path coefficient for girls represented a significantly larger effect. When we compared the freely estimated path from perceived control to depressive symptoms with the fully constrained model, we found no differences, χ2(1, N = 474)) = 3.04, p = .08, suggesting the relationship between perceived control and depressive symptoms, although appearing different, was comparable for boys and girls in this sample.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the links between academic competence and depressive symptoms, specifically, the role of control-related beliefs in mediating this relationship. Results supported the hypothesized path models from academic competence in first grade to depressive symptoms in seventh grade, controlling for a host of correlated constructs (conduct problems, inattention, peer relations). Perceived control in sixth grade mediated the effect of academic competence on depressive symptoms. Although the models worked for both boys and girls, the path coefficients were notably larger for girls; in particular, multiple-group analysis revealed a statistically stronger effect of academic competence on perceived control for girls. The effects held when controlling for conduct problems, inattention, and peer relations in first grade, suggesting that the path model was specific to low academic competence rather than to a more general externalizing or social rejection pathway.

The findings are consistent with a life course/social field perspective and with Cole, Jacquez, and Maschman’s (2000) competency model of depression. Actual academic skill deficits may place children at risk for developing negative perceptions of control that are known to be associated with depressive symptoms. The findings are also in line with the looking glass hypothesis. Cole hypothesized that significant others, such as peers and teachers, accurately perceive low academic competence and communicate these perceptions to children with skill deficits. In turn, these children are more likely to perceive themselves as academically incompetent on the basis of these perceptions of others.

Given past evidence that girls are more likely than boys to underestimate their academic abilities and also to attribute failures to their low ability (Frey & Ruble, 1987; Willcutt & Pennington, 2000), we expected the hypothesized relationships to be especially strong for girls. The constrained model fit well for both boys and girls; however, the effect sizes for girls were notably larger. Multiple-group analysis indicated that the effect of academic competence on perceived control was significantly stronger for girls. In other words, low academic skills at school entry lead children, especially girls, to believe that they have less influence over important outcomes in their life. These beliefs, in turn, serve as risk factors for depressive symptoms.

More generally, the findings raise questions about the role of academic competence in depression. Is there a threshold of academic competence below which children are at elevated risk for becoming depressed? Rather than a threshold, the present data imply a continuum of risk associated with low academic competence given that academic competence and depression were linearly related. Cultural imperatives, such as reading and writing skills, are laced with social meaning and may serve as a basis for social comparisons across the full spectrum of academic skills. Because individual differences will exist in basic academic skills even if educators improve instructional quality for all children, it may be necessary to explore and emphasize other assets for all children (e.g., other academic, interpersonal, athletic, musical skills), especially those with lower academic skill relative to their peers.

Subsequent studies are needed to chart the path from academic competence to perceived control, particularly the emergence of academic and social self-perceptions. Because perceived control was only measured in sixth grade in this study, we were unable to examine the nuanced development of perceptions of control during the elementary grades. The present study relied on an aggregate measure of perceived control in sixth grade that included both academic and social domains. It would be informative to explore the interactions between academic and social self-perceptions in relation to academic competence across development. A reasonable hypothesis is that low academic competence may initially lower perceptions of control in the academic domain but over time may influence perceptions of social control. After all, the most enduring consequence of low academic skills is likely not just how children come to view themselves as students but rather how they come to view themselves as social beings. In school, one of the main ways children can get others to like them is by being a good student. Children with low academic skills may come to believe, perhaps accurately, that they have one less method for influencing important social outcomes.

The findings have implications for understanding the development of these commonly co-occurring problems (low academic competence and depression) and for the design of preventive interventions to disrupt the progression of depressive symptoms in children. Specifically, the findings suggest that early identification of academic problems and amelioration of any associated academic problems may reduce risk for subsequent depressive cognitions and symptoms, perhaps especially so for girls. Instructional interventions to promote academic skills and success and efforts to increase academic engagement by altering school climate may help alleviate some of their risk for internalizing symptoms.

Given the well-documented achievement disparities between African American children and other groups of children in the United States (National Center for Education Statistics, 2005a, 2005b), the findings also have implications for the identification and treatment of academic problems in African American children. Failure to identify and treat academic problems may place many African American children at greater risk for academic failure and, in turn, depressive symptoms. Efforts to improve the identification and treatment of academic problems among African American children could yield the additional benefit of reducing their risk for depressive symptoms.

We used a community epidemiologically defined sample of children in the present study, which may be viewed an asset. Additionally, we extended prior research by analyzing longitudinal data for an understudied population. The study relied on continuous measures of key study variables rather than diagnostic data; thus, it is unknown whether the relationships described apply equally well to children with clinical diagnoses. Additionally, we measured academic competence, perceived control, and depressive symptoms at single points in time. Future studies using multiple time point assessments of these constructs (e.g., growth modeling) could improve the reliability of assessment and estimates.

The study provides guidance to counseling psychologists interested in the prevention of enduring emotional symptoms during early childhood. Counseling psychologists who are working with young African American children should be mindful of their academic performance. Academic problems pose a significant risk for children’s present and future emotional well-being. The findings in the present study suggest the importance of regular ongoing consultation with teachers to assess children’s academic performance and advocacy for early and intensive academic supports when indicated. Additionally, it is critical for counseling psychologists who are working with underachieving African American youth to find ways to highlight their nonacademic skills and assets and work with their caregivers and teachers to do the same. Hudley, Graham, and Taylor (2007) recently described an intervention model focused on promoting academic engagement and motivation that may be particularly useful in this regard. In their initial trial, the intervention significantly enhanced young children’s attributions in academic and social realms.

Concurrently, clinicians may also focus on promoting the ethnic identity of African American children as a protective factor against depression. Yasui, Dorham, and Dishion (2004) found that ethnic identity had especially strong predictive relations with indicators of emotional and academic well-being for African American youth. Similarly, Eccles, Wong, and Peck (2006) conceptualized ethnic identity as a central adaptive mechanism for African American youth to buffer their experiences of perceived discrimination and bolster their academic self-concept, motivation, and achievement.

Counseling psychology researchers are encouraged to contribute to the growing literature about early social-environmental risk factors for depression and methods to prevent these problems. Future studies are needed to examine the relationships between the variables in the present investigation and other related variables, including life stressors, social competence, and additional components of attributional style and family environment. Further clarification of the developmental pathway to depression for children may lead to improved prevention and treatment interventions for these children.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Study Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 Math | — | |||||||||

| 2. T1 Reading | .69* | — | ||||||||

| 3. T1 Depression | −.07 | −.05 | — | |||||||

| 4. T1 Conduct problems | −.19* | −.19* | .05 | — | ||||||

| 5. T1 Attention problems | −.51* | −.49* | .07 | .48* | — | |||||

| 6. T1 Peer relations | .31* | .30* | −.09 | −.37* | −.48* | — | ||||

| 7. T2 Academic perceived control | .15* | .17* | −.14 | .02 | −.08 | .04 | — | |||

| 8. T2 Social perceived control | .19* | .17* | −.14 | −.05 | −.13 | .11 | .39* | — | ||

| 9. T3 Depression | −.19* | −.18* | .06 | .05 | .07 | −.07 | −.31* | −.30* | — | |

| 10. Intervention status | −.05 | −.02 | .01 | .04 | .16* | −.04 | .05 | .00 | −.01 | — |

Note. N = 474. T1 = first grade, T2 = sixth grade, T3 = seventh grade

p < .05.

Contributor Information

Keith C. Herman, Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology, University of Missouri—Columbia

Sharon F. Lambert, Department of Psychology, George Washington University

Wendy M. Reinke, Department of Educational, School, and Counseling Psychology, University of Missouri—Columbia

Nicholas S. Ialongo, School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1987. rev. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text rev. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Williams S, McGee R, Silva P. Cognitive and social correlates of DSM-III disorders in preadolescent children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1989;28:842–846. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Carlson GA. Depression Self-Rating Scale: Utility with child psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:491–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.4.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudek R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carton JS, Nowicki S. Antecedents of individual differences in locus of control of reinforcement: A critical review. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs. 1994;120:31–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Developmental psychopathology and disorders of affect. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Risk, disorder, and adaptation (Vol) New York: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Jacquez FM, Maschman TL. Social origins of depressive cognitions: A longitudinal study of self-perceived competence in children. Cognitive Therapy & Research. 2001;25:377–395. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Peeke L, Henderson A, Harwell J. Validation of depression and anxiety measures in Euro-American and African American youths: Multitrait–multimethod analyses. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Martin JM, Powers B, Truglio R. Modeling causal relations between academic and social competence and depression: A multitrait–multimethod longitudinal study of children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:258–270. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Rehm LP. Family interaction patterns and childhood depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1986;14:297–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00915448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Turner JE. Models of cognitive mediation and moderation in child depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:271–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CTBS. Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills. 4. Monterey, CA: Author/McGraw-Hill; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, Leggett EL. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review. 1988;95:256–273. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Wong CA, Peck SC. Ethnicity as a social context for the development of African American adolescents. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:407–426. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Buchanan CM, Flanagan C, Fulgini A, Midgley C, Yee D. Control versus autonomy during early adolescence. Journal of Social Issues. 1991;47:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham F, Cain K. Learned helplessness in humans: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review. 1986;6:301–333. [Google Scholar]

- Frey KS, Ruble DN. What children say about classroom performance: Sex and grade differences in perceived competence. Child Development. 1987;58:1066–1078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme P, Eccles J. Underestimation of academic ability in the middle school years. Paper presented at the biennial meetings of the Society for Research in Child Development; Indianapolis, IN. 1995. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Lambert S, Ialongo N, Ostrander RO. Academic pathways between attention problems and depressive symptoms among urban African American children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35:265–274. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman KC, Ostrander RO. The effects of attention problems on depression: Developmental, cognitive, and academic pathways. School Psychology Quarterly. 2007;22:483–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: Causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:127–155. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GN. Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:599–610. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hudley C, Graham S, Taylor A. Reducing aggressive behavior and increasing motivation in school. Educational Psychologist. 2007;42:251–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Edelsohn G, Kellam SG. A further look at the prognostic power of young children’s reports of depressed mood. Child Development. 2001;72:736–747. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Kellam SG, Poduska J. Tech Rep No 2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 1999a. Manual for the Baltimore How I Feel. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Kellam SG, Poduska J. Tech Rep No 4. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 1999b. Manual for the Peer Nomination Inventory. [Google Scholar]

- Ialongo NS, Poduska J, Werthamer L, Kellam S. The distal impact of two first-grade preventive interventions on conduct problems and disorder in early adolescence. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2001;9:146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Rodgers A, Colbus D. The Hopelessness Scale for Children: Psychometric characteristics and concurrent validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:241–245. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Brown CH, Rubin BR, Ensminger ME. Paths leading to teenage psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse: Developmental epidemiological studies in Woodlawn. In: Guze SB, Earls FJ, Barratt JE, editors. Childhood psychopathology and development. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kellam SG, Rebok GW, Mayer LS, Ialongo N, Kalodner CR. Depressive symptoms over first grade and their response to a developmental epidemiological based preventive trial aimed at improving achievement. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:463–481. [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA, David CF, White BA. Ethnic and sex differences in children’s depressive symptoms: The mediating role of academic and social competence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:341–350. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner JA, David-Ferdon CF, Lewis CM, Dunkel SB. Ethnic and sex differences in children’s depressive symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:171–181. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ. Modeling the dropout mechanism in repeated measures studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Reading problems and depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:219–229. doi: 10.1023/a:1022534527021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinn LK, Cukor D, Sanderson WC. The relationship between parenting style, cognitive style, and anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2005;29:219–245. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Author; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using the EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;6:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser F, Wisenbaker J. A Monte Carlo Study investigating the impact of item parceling on measures of fit in confirmatory factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2003;63:729–757. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. The nation’s report card: Math 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. The nation’s report card: Reading 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2005b. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls JG, Miller AT. Reasoning about the ability of self and others: A developmental study. Child Development. 1984;47:990–997. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrander R, Herman KC. Potential developmental, cognitive, and parenting mediators of the relationship between ADHD and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:89–98. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrander R, Weinfurt KP, Yarnold PR, August GJ. Diagnosing attention deficit disorders with the Behavioral Assessment System for Children and the Child Behavior Checklist: Test and construct validity analysis using optimal discriminant classification trees. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:660–672. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Chamberlain P. Outcomes and methodological issues relating to treatment of antisocial children. In: Giles TR, editor. Handbook of effective psychotherapy. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 43–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik E, Prinz R, Leibert C, Weintraub S, Neal J. The Pupil Evaluation Inventory: A sociometric technique for assessing children’s social behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1976;4:83–97. doi: 10.1007/BF00917607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Factor structure and construct validity of “What I Think and Feel”: The Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1979;43:281–283. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4303_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Kurlakowsky KD, Conley CS. Developmental and social-contextual origins of depressive control-related beliefs and behavior. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:447–475. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MH, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, Connell JP. Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1998;63(2–3) Serial No. 254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, McCarty CA. Control-related beliefs and depressive symptoms in clinic-referred children and adolescents: Developmental differences and model specificity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:97–109. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Southam-Gerow MA, Sweeney L. The Perceived Control Scale for Children. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Sweeney L, Proffitt V, Carr T. Control-related beliefs and self-reported depressive symptoms in late childhood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:411–418. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werthamer-Larsson L, Kellam SG, Wheeler L. Effect of first-grade classroom environment on child shy behavior, aggressive behavior, and concentration problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1991;19:585–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00937993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcutt EG, Pennington BF. Psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with reading disability. Journal of Child Psycholology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:1039–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui M, Dorham CL, Dishion TJ. Ethnic identity and psychological adjustment: A validity analysis for African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2004;19:807–825. [Google Scholar]