Abstract

Objective

To describe weight misperception and to examine the influence of sociodemographic factors on underestimation of weight status in Caucasian, Latino, Filipino, and Korean Americans.

Design

Data from 886 non-pregnant adults who participated in a cross-sectional survey administered in English, Spanish, and Korean, were analyzed. The actual weight status derived from the participants’ body mass index (BMI) categories and their perceived weight status were compared. A multiple logistic regression model was used to explore if underestimation of weight status was associated with ethnicity, gender, and education level.

Results

Caucasians, Latinos, Filipinos, and Koreans represented 19.4%, 26.8%, 27.4%, and 26.4% of the total sample of 886. Overall, 2 in 3 participants correctly perceived their weight status, but 42% of Latinos underestimated their weight status and 22% of Koreans overestimated their weight status. Latino ethnicity, male, and low education (≤ high school) were related to greater underestimation of weight status (p < 0.05). In contrast, Korean ethnicity was related to less underestimation of weight status (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Misperception of weight status should be counted in any efforts to develop a weight management intervention for Latino and Korean Americans.

Keywords: Body-Mass Index, BMI, Weight status, Latino, Filipino, Korean

Introduction

In the United States (US), more than two-thirds of adults (68.5%) are overweight or obese.1 Being overweight or obese not only increases the risk of developing adverse health problems including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, and certain types of cancers,2 but also places an economic burden on individuals and the healthcare system.3 In 2008, the estimated direct and indirect costs related to obesity increased to $147 billion in the U.S.4 These costs are expected to escalate if no action is taken to reduce this obesity epidemic.

The prevalence of overweight/obese populations among some racial and ethnic minority groups is significantly higher than Caucasians (i.e., non-Hispanic Blacks and Mexican Americans).5 Although the prevalence of overweight/obese in Asian Americans as a group has been lower than Caucasians, dramatic increases in the prevalence of overweight/obesity among some Asian subgroups (e.g. Asian Indians, Filipinos) were observed in 1992–2011 National Health Interview Survey. Between 1992 and 2011, the overweight/obese prevalence increased from 33.2% to 69.7% for Filipinos and from 22.4% to 32.9% for Koreans.6 Moreover, Asian Americans are known to experience higher all-cause and obesity-related mortality/morbidity risk at lower body mass index (BMI) compared to Caucasians. 7,8,9 These findings suggest we closely monitor obesity risks in racial and ethnic minorities including Asians.

An individual’s weight perception can be different from his or her actual weight status and weight misperception, especially underestimation, may be one of obesity risks or barrier to any attempts to manage healthy body weight. Overweight/obese adults who misperceived their weight were less likely to report weight management behaviors than those with a correct weight perception in a nationally representative sample from the 1999–2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).10 Weight misperception is often reported among the US public and it is known to vary depending on sociodemographic factors such as racial and ethnic minority status, gender, and socioeconomic status.11,12 Thus, this study was focused on examining the influence of these factors on weight misperception, especially underestimation of weight status among ethnic minority groups and Caucasians.

Some evidence shows that underestimation of weight status is higher among Latinos than Caucasians.12,13 Although Asian Americans are among the fastest-growing racial groups, the literature on weight misperception among Asian Americans is scant. Within Asian Americans, Filipinos and Koreans, have a higher prevalence of type 2 diabetes compared to Caucasians, despite a low prevalence of overweight/obesity.14 That is, it is noteworthy to examine weight perception among those underrepresented ethnic minority groups. Thus, the purpose of this study was: 1) to describe discrepancies between actual weight status and perceived weight status and 2) to examine the influence of sociodemographic factors on underestimation of weight status in Caucasian, Latino, Filipino, and Korean American community-dwelling women and men.

Methods

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional survey, entitled “the Digital Link to Health (DiLH) Survey,” was conducted to develop a culturally tailored diabetes prevention program for understudied high-risk racial and ethnic groups including Latino, Filipino, and Korean Americans in the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego.15,16 Online or paper surveys were administered in English, Spanish, and Korean. From August to December 2013, 1,039 adults who were 18 years or older and reported no history of diabetes participated in the study. Among participants, 905 individuals were identified themselves as Caucasian, Latino, Filipino, or Korean and 134 identified themselves as other racial/ethnic groups. Of these 905, individuals with missing data on gender (n=1) and being pregnant (n=1), and pregnant women (n=17) were excluded. The sample for analysis consisted of 886 individuals (171 Caucasians, 238 Hispanics, 243 Filipinos, 234 Koreans). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research (CHR) at the University of California, San Francisco.

Procedures

Participants were recruited both online and in person. Online survey links in English, Spanish, and Korean were posted on Craigslist and websites that target on Filipino, Korean, or Latino on a weekly basis. Bilingual staff screened potential participants at the community events and churches. The community events included ethnic specific (e.g., Korean Day Cultural Festival, Pistahan Philippine Festival) and local (e.g., North Fair Oaks Community Festival, Presidio Picnic & Food Truck Fair) festivals, community health fairs, as well as, three multiethnic and three mono-ethnic churches. Participants completed the self-administered survey independently. If participants had questions or preferred verbal administration, bilingual staff were available to answer specific questions or read the survey to participants. An online link was provided to participants who preferred to take the survey online at community events. Overall, it took approximately 15 minutes to complete the entire survey. Participants who completed a paper survey were given a complimentary tote bag and those who completed the online survey had the option of entering a $25 gift card raffle.

Data collection and key measurements

Classification of calculated weight status

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (weight [kg]/squared height [m2]) on self-reported weight and height. According to the WHO expert consultation panel’s recommendation, the WHO classification for Asians was used for Filipino Americans and Korean Americans since the standard WHO classification has shown the tendency to underestimate obesity-related risks in Asian populations.9 The WHO classification for Asians is as follows: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI between 18.5 and 22.99 kg/m2), overweight (BMI between 23.0 and 27.49 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥ 27.5 kg/m2). For Caucasians and Latinos, the standard WHO classification was adopted: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI between 25.0 and 29.9 kg/m2) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2).

Classification of perceived weight status

The perceived weight status was assessed by the question: “Do you know if you are?” The response options for the question were “underweight,” “normal weight,” “overweight,” “obese,” and “don’t know.” Those who chose “don’t know” response option were excluded from the further analyses.

Classification of weight misperception

If the participant’s calculated weight status and perceived weight status were in agreement they would be classified as accurate. If there were a discrepancy between the participant’s calculated weight status and perceived weight status they would be classified as weight misperception. Individuals who reported their perceived weight status at least one category above their BMI categories were classified as overestimation and those who reported their perceived weight status at least one category below their BMI categories were classified as underestimation.

Education level was asked and it was classified into three categories: 1) high school or less, 2) some college or college, and 3) graduate school level. Age, gender, pregnancy (whether they are currently pregnant), race/ethnicity, the primary language spoken at home, survey administration mode (either online or paper) were assessed. Weight loss attempts during the last month were assessed with a dichotomous question (Yes/No) and an additional open-ended question to describe the weight loss attempts. All the responses were categorized based on pre-determined coding systems. Experience of participating in commercial weight loss programs was also assessed with a dichotomous question (Yes/No) with a list of commercial weight loss programs.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe 4 racial and ethnic group’s sociodemographic and weight related characteristics. Differences among the 4 racial and ethnic groups were compared using one-way ANOVAs for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. The proportions of 4 BMI categories based on self-reported weight and height, and 4 categories of perceived weight status were compared in each racial and ethnic group. A multiple logistic regression model was examined with underestimation of weight status as the dependent variables, and ethnicity, gender, and education level as independent variables. The model was controlled for age, speaking English as primary language at home, and survey administration mode. Statistical significance was set at p-value 0.05. Analysis of the data was conducted using the SPSS 21.0.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

Caucasians, Latinos, Filipinos, and Koreans represented 19.4%, 26.8%, 27.4%, and 26.4% of the total sample of 886. The sociodemographic and weight related characteristics of participants across 4 racial and ethnic groups are detailed in Table 1. The overall mean age was 44.4 (SD ± 16.1) years and 63.5% were female. About 27% reported high school or less than high school as their highest level of education. About 45% reported English as a primary language spoken at home.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and weight characteristics across four racial/ethnic groups

| Variables | All | Caucasian | Latino | Filipino | Korean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (± SD) or % (n) | Mean (± SD) or % (n) | Mean (± SD) or % (n) | Mean (± SD) or % (n) | Mean (± SD) or % (n) | Overall p-value | |

| Age (years) (n=878) | 44.4 (±16.10) | 45.0 (±16.12) | 41.7 (±14.02) | 41.24 (±18.16) | 49.94 (±14.34) | <.001 |

| Gender (n=886) | .014 | |||||

| Female | 63.5 (563) | 72.5 (124) | 64.3 (153) | 63 (153) | 56.8 (133) | |

| Male | 36.5 (323) | 27.5 (47) | 35.7 (85) | 37 (90) | 43.2 (101) | |

| Education (n=883) | <.001 | |||||

| High School or some high school | 27.1 (239) | 11.1 (19) | 62.3 (147) | 13.4 (32) | 17.5 (41) | |

| College or some college | 57.5 (508) | 63.7 (109) | 34.7 (82) | 74.8 (181) | 58.1 (136) | |

| Graduate school | 15.4 (136) | 25.1 (43) | 3 (7) | 12 (29) | 24.4 (57) | |

| English as Primary Language (n=886) | <.001 | |||||

| Yes | 44.6 (395) | 98.2 (168) | 18.1 (43) | 66.7 (162) | 9.4 (22) | |

| No | 55.4 (491) | 1.8 (3) | 81.9 (195) | 33.3 (81) | 90.6 (212) | |

| Height (inch/cm) | 98.6 (874) | 100 (171) | 95.8 (228) | 99.6 (242) | 99.6 (233) | <.001 |

| Weight (lb/kg) | 98.4 (872) | 100 (171) | 97.5 (232) | 97.9 (238) | 98.7 (231) | .204 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n= 866) | 25.5 (± 5.33) | 25.6 (± 6.05) | 27.9 (± 5.53) | 25.5 (± 5.22) | 23.1 (± 3.22) | <.001 |

| BMI categories based on self-reported height & weight n=866 (Asian BMI applied to Filipinos and Koreans) | <.001 | |||||

| Underweight | 2.7 (23) | 1.8 (3) | 1.3 (3) | 2.5 (6) | 4.8 (11) | |

| Normal weight | 52.4 (454) | 52.6 (90) | 33.2 (75) | 52.1 (124) | 71.4 (165) | |

| Overweight | 27.9 (242) | 26.9 (46) | 33.2 (75) | 30.3 (72) | 21.2 (49) | |

| Obese | 17 (147) | 18.7 (32) | 32.3 (73) | 15.1 (36) | 2.6 (6) | |

| Do you know your BMI? (n=884) | <.001 | |||||

| No | 86.4 (764) | 74.9 (128) | 95.8 (228) | 83.5 (202) | 88.4 (206) | |

| Yes | 13.6 (120) | 25.1 (43) | 4.2 (10) | 16.5 (40) | 11.6 (27) | |

| Do you know if you are (n=884) | <.001 | |||||

| Underweight | 4 (35) | 2.3 (4) | 4.2 (10) | 2.5 (6) | 6.4 (15) | |

| Normal weight | 46.8 (414) | 53.8 (92) | 33.3 (79) | 49.2 (119) | 53 (124) | |

| Overweight | 37 (327) | 29.2 (50) | 45.1 (107) | 36 (87) | 35.5 (83) | |

| Obese | 6.3 (56) | 11.1 (19) | 5.5 (13) | 7 (17) | 3 (7) | |

| Don’t know | 5.9 (52) | 3.5 (6) | 11.8 (28) | 5.4 (13) | 2.1 (5) | |

| Weight perception (n=816) | ||||||

| Correctly perceived | 66.9 (546) | 77.6 (128) | 53.2 (107) | 69.6 (156) | 68.6 (155) | <.001 |

| Overestimated | 11.4 (93) | 6.7 (11) | 4.5 (9) | 10.7 (24) | 21.7 (49) | <.001 |

| Underestimated | 21.7 (177) | 15.8 (26) | 42.3 (85) | 19.6 (44) | 9.7 (22) | <.001 |

| Have you tried to lose weight during the last month? (n=877) | <.001 | |||||

| No | 52.5 (460) | 62.6 (107) | 52.4 (120) | 41.6 (101) | 56.4 (132) | |

| Yes | 47.5 (417) | 37.4 (64) | 47.6 (109) | 58.4 (142) | 43.6 (102) | |

| Weight loss strategies (n=886) | ||||||

| Diet | 33.4 (296) | 32.2 (55) | 31.1 (74) | 38.3 (93) | 31.6 (74) | <.001 |

| Reducing caloric intake | 18.2 (161) | 15.8 (27) | 10.1 (24) | 21.8 (53) | 24.4 (57) | |

| Healthier diet | 12.9 (114) | 16.4 (28) | 21 (50) | 11.5 (28) | 3.4 (8) | |

| Self-monitoring | 2.4 (21) | 3.5 (6) | .8 (2) | 4.5 (11) | .9 (2) | |

| Changing eating pattern | 1.9 (17) | 1.2 (2) | 1.3 (3) | 2.9 (7) | 2.1 (5) | |

| Fasting and/or detox | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | .4 (1) | 0 (0) | 3.4 (8) | |

| Dietary supplement | .8 (7) | 1.2 (2) | .4 (1) | 1.2 (3) | .4 (1) | |

| Other | 1.4 (12) | 4.7 (8) | .4 (1) | .8 (2) | .4 (1) | |

| Physical Activity | 31.7 (281) | 25.1 (43) | 29.8 (71) | 41.6 (101) | 28.2 (66) | <.001 |

| Endurance activity | 30.9 (274) | 22.2 (38) | 29.8 (71) | 41.6 (101) | 27.4 (64) | |

| Muscle strengthening | 1 (9) | 0 (0) | .8 (2) | 1.2 (3) | 1.7 (4) | |

| Flexibility activity | .8 (7) | .6 (1) | .4 (1) | .8 (2) | 1.3 (3) | |

| Commercial program | 9.6 (85) | 21.6 (37) | 10.1 (24) | 7.8 (19) | 2.1 (5) | <.001 |

| Weight Watchers | 5.6 (50) | 17.5 (30) | 2.9 (7) | 3.7 (9) | 1.7 (4) | |

| Nutritionist | 4 (35) | 7 (12) | 6.3 (15) | 2.5 (6) | .9 (2) | |

| South Beach Diet | 1.8 (16) | 4.7 (8) | 1.7 (4) | 1.2 (3) | .4 (1) | |

| Nutrisystem | 1.5 (13) | 2.3 (4) | 1.7 (4) | 1.2 (3) | .9 (2) | |

| Jenny Craig | 1 (9) | 2.9 (5) | .4 (1) | .8 (2) | .4 (1) | |

Note: some variables have missing data. Overall p-value represents the results of ANOVAs for continuous measures and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Weight status characteristics

The overall mean BMI was 25.5 (SD ± 5.33) kg/m2, with 27.9% and 17% of the sample were “overweight” and “obese” respectively based on their calculated BMI scores. Latinos had highest proportions for overweight (33%) and obesity (32%) among all racial and ethnic groups. Approximately 14% (n=120) of the participants reported they knew their BMI scores. However, only 8% (n=72) estimated their BMI scores within ± 2 kg/m2 from the calculated BMI. The proportion of those who could estimate their BMI scores within ± 2 kg/m2 from the calculated BMI varied across ethnic groups (17% for Caucasians to 2.5% for Latinos). Moreover, among the groups, the proportion of individuals unable to report their height in inches or centimeters was highest in Latinos (4.2%).

Regarding participants’ perceived weight status, 37% and 6.3% considered themselves as overweight and obese, respectively, while approximately 6% did not know their weight status. The proportion of individuals who did not know their weight status was the highest (11.1%) among Latinos compared to Caucasians, Filipinos, and Koreans (3.5%, 5.5%, 2.2%, respectively). Overall, 67% accurately perceived their weight, 22% underestimated, and 11% overestimated. About 78% of Caucasians correctly perceived their weight followed by Filipinos (69.6%), Koreans (68.6%), and Latinos (53.2%). Approximately 42% of Latinos underestimated their weight status, followed by Filipinos (19.6%), Caucasians (15.8%), and Koreans (9.7%). Weight status was overestimated by 22% of Koreans, followed by Filipino Americans (10.7%), Caucasians (6.7%), and Latinos (4.5%).

Roughly one out of two participants (48%) reported they tried to lose weight during the last month, and one-third reported either diet and/or physical activity as their weight loss strategies. Overall participation in commercial weight loss program (e.g., Weight Watchers, South Beach Diet, Nutritionist) was relatively low with (21.6%) Caucasians indicating past participation in commercial weight loss programs compared to Latinos (10.1%), Filipinos (7.8%), and Koreans (2.1%)

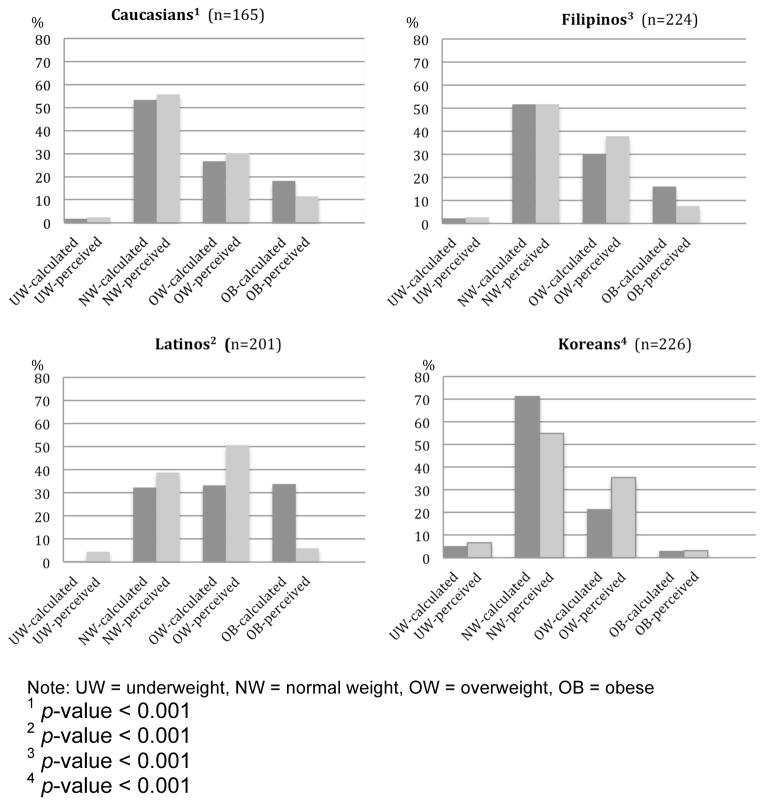

Calculated vs. perceived weight status proportions

Figure 1 shows the proportions of weight status classification according to 1) the calculated BMI and 2) perceived weight status across 4 racial and ethnic groups. Among Latinos, Filipinos, and Caucasians, there were wide discrepancies between BMI-classified obese individuals and those who self-classified themselves as obese. For example, 32.3% of Latinos were obese, but only 5.3% perceived themselves as obese. A similar pattern of weight underestimation was shown by BMI-classified obese Caucasians and Filipinos. In contrast, Koreans classified by BMI as normal weight tended to overestimate their weight status. Among Koreans only 53.7% perceived their weight status as normal even though 71.4% actually fell within normal BMI weight limits.

Figure 1.

Proportions of Individuals in BMI Categories (calculated vs. perceived) across four racial/ethnic groups

Note: UW = underweight, NW = normal weight, OW = overweight, OB = obese

1 p-value < 0.001

2 p-value < 0.001

3 p-value < 0.001

4 p-value < 0.001

Multiple logistic regression

Table 2 summarizes the results of the multiple logistic regression in predicting underestimation of weight status and its known risk factors, controlling for age, speaking English as primary language at home, and survey administration mode. Latino ethnicity (Adjusted Odds Ratio (OR) = 2.18; 95% CI = 1.09 – 4.36), male (Adjusted OR = 1.62; 95% CI = 1.12–2.33), and low education (≤ high school) (Adjusted OR = 2.16; 95% CI = 1.11–4.20) were significantly related to greater underestimation of weight status (p < 0.05) compared to Caucasians, female gender, and higher education (≥ graduate school). On the other hand, Korean ethnicity (Adjusted OR = .38; 95% CI = 0.18–0.82) was significantly related to less underestimation of weight status (p < 0.05), compared to Caucasians.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression predicting underestimation of weight status (N=8081))

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 1.00 | -- | <.0012) |

| Latino | 2.18 | 1.09 – 4.36 | .03 |

| Filipino | 1.17 | .64 – 2.14 | .60 |

| Korean | .38 | .17 – .82 | .01 |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.00 | -- | |

| Male | 1.62 | 1.12 – 2.33 | .01 |

| Education | |||

| Graduate school | 1.00 | -- | <.0051) |

| College or some college | .97 | .54 – 1.75 | .92 |

| ≤ High school | 2.16 | 1.11 – 4.20 | .02 |

| Age | 1.01 | 1.00 – 1.02 | .13 |

| English as primary language | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | -- | |

| No | .77 | .47 – 1.27 | .31 |

| Survey administration mode | |||

| Paper | 1.00 | -- | |

| Online | .94 | .58 – 1.52 | .80 |

Note. Adjusted for age, speaking English as primary language at home, and survey administration mode.

CI = confidence interval for odds ratio

78 cases excluded due missing values

Overall p-value

Discussion

The aims of the study are to examine the discrepancies between the actual weight status and perceived weight status, and to examine the influence of sociodemographic factors on underestimation of weight status in Caucasians, Latinos, Filipinos, and Koreans. While the majority of the Caucasians could report their heights and weights, there were small proportions of racial and ethnic minorities who could not report their heights (in either centimeters or inches) and weights (in either kilograms or pounds). This lack of awareness suggests a significant proportional disconnect in weight estimation and subsequent weight misperception among racial and ethnic minorities. For example, 11% of the Latinos could not report their weight status and 42% of the Latinos underestimated their weight status. Latinos also reported the lowest level of knowing their BMIs (about 4%) and only 2.5% could actually estimate their BMIs within ± 2 kg/m2 from the calculated BMI. Given that two thirds of Latinos in the study were either overweight or obese, their reported lack of awareness of height, weight, BMI, and weight status should be considered when developing interventions to promote weight loss among this population.

BMI is a reliable screening tool of overweight and obesity and significantly correlated with total body fat content.17 Since BMI is calculated from the information collected easily (height and weight), it has become a recognized indicator for overweight or obesity. However, only 14% of the sample reported that they knew their BMI score and only 8% of the sample correctly estimated their BMIs (within ± 2 kg/m2 from the calculated BMI). Compared to Caucasians, Latino, Filipino, and Korean Americans consistently reported lower levels of knowing their BMIs and fewer could correctly estimate their BMI scores in the study. Lack of BMI awareness especially among racial/ethnic minority groups, is especially noteworthy. Efforts to increase public awareness of BMI and cut-off points for overweight and obesity classification should be made, especially for racial/ethnic minority groups.

It is widely recognized that weight perception is influenced by culture and norm,18 however, there is dearth of research on Asian Americans’ weight perception. In our study, fewer Filipinos and Koreans correctly perceived their weight status than Caucasians and more Filipinos and Korean either underestimated or overestimated than Caucasians. The proportions of those who knew their BMI among Filipinos and Koreans were also lower than that of Caucasians. Especially, Koreans showed the tendency of overestimation compared to Caucasians. According to the 2009 Korean Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS), about 12% of Korean adolescent participants were actually overweight or obese, but about 38% of all participants perceived themselves as overweight or obese.19 In an international study with young adults from 22 countries including Koreans, Asians consists of young adults from Korea, Japan, and Thailand consistently showed higher prevalence of overestimation of weight status compared to those from other regions of countries.20 Korean Americans may be influenced by Korean culture and norm of “thin ideal.” This finding suggests that racial and ethnic minorities may consider their own racial/ethnic group as their reference group to evaluate their weight status. Thus, it is important to assess cultural acceptance of obesity and cultural norm for healthy weight status for each racial and ethnic group when researchers design a weight management intervention.

We explored the effects of ethnicity, gender, and education level on underestimation of weight status controlling for age, speaking English as primary language at home, and survey administration mode. Latinos, men, and individuals with lower education level were more likely to underestimate their weight status whereas Koreans were less likely to underestimate their weight status. The significant racial and ethnic differences in weight perception among Latinos are consistent with other studies, which show that Latinos living in the U.S. are less likely to consider themselves as overweight than Caucasians.12,13 Given the high prevalence of obesity among Latinos, their high tendency of underestimating weight status need health professionals’ attention and cultural factors that may influence their attitudes to weight should be further explored. Our study findings show that men were more likely to underestimate their weight status than women. It may indicate common cultural phenomenon for underestimation or under-concern among men, and overestimation or over-concern among women. Given the higher prevalence of overweight and obesity among men (74%) than women (64%) among the U.S. adults, our findings highlight the need to focus men as much as women in weight loss interventions.21 In addition, it is important to increase the awareness of perceived weight status among those with low education level since obesity is disproportionately affecting those who are in low socioeconomic status in the U.S.5

Strengths and Limitations

The major limitation of this study is the use of self-reported weight and height. Potential bias due to under- or over-reporting cannot be eliminated, but the use of self-reported weight and height is considered sufficiently accurate in epidemiological setting.22 Another limitation is the samples of Caucasians, Latinos, Filipinos, and Koreans may not represent the populations living in the U.S. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this study represents the first attempts to describe perceived weight status in under-represented racial and ethnic minority groups, and presents the evidence of possible associations among ethnicity, gender, education level, and underestimation of weight among these groups.

Implications

To prevent the epidemic of obesity in our society, the perceived underestimation of weight status among Latinos, male, and individuals with low education level should be addressed and these populations should be targeted in future studies and public education programs. Perceived weight status may assist in explaining discrepancies between clinical recommendations based on weight status and actual weight loss attempts. Health care providers should investigate how a patient perceive his/her weight status and what kind of weight management attempts are being made if there are any, in addition to obtaining actual weight status. As our findings indicate, majority of people are not familiar with BMI and do not know their BMI scores. Raising public awareness of BMI and a message like “Know Your Number” should be promoted, especially, among racial and ethnic minorities.

Acknowledgments

This survey was supported by the National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (R01HL104147 & 3R01HL104147-02S1) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Nursing Research, NIH (#2 T32 NR07088-18), and University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing Fund. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We also thank the outreach staff at Vista Community Clinic and volunteers, Monica Cruz, BS, Dilma Fuentes, Jeongeun Heo, AS, Helen Kim, BS, Jihyeon Lee, BS, Claire Pham, BS, Roy Salvador, BS, RN, Joelle Takahashi, BA, and Amalia Dangilan Fyles, RN, CNS, MSN, CDE at San Francisco General Hospital.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NIH. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res. 1998;6(Suppl 2):51S–209S. published erratum appears in Obes Res 1998;Nov 6(6):464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quesenberry CP, Caan B, Jacobson A. Obesity, health services use, and health care costs among members of a health maintenance organization. Arch Intern Med. 1998 Mar;158(5):466–472. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual Medical Spending Attributable To Obesity: Payer- And Service-Specific Estimates. Health Affairs. 2009;5:w822–w831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Beydoun MA. The obesity epidemic in the United States – gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev. 2007;29:6–28. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxm007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh GK, Lin SC. Dramatic increases in obesity and overweight prevalence among Asian Subgroups in the United States, 1992–2011. ISRN Prev Med. 2013;2013:898691. doi: 10.5402/2013/898691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jih J, Mukherjea A, Vittinghoff E, Nguyen T, Tsoh JY, Fukuoka Y, Bender MS, Tseng W, Kanaya AM. Using appropriate body mass index cut points for overweight and obesity among Asian Americans. Prev Med. 2014;65:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen CP, David Cheng TY, Tsai SP, Chan HT, Hsu HL, Hsu CC, Eriksen MP. Are Asians at greater mortality risks for being overweight than Caucasians? Redefining obesity for Asians. Public Health Nutrition. 2009;12(4):497–506. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorsey R, Eberhardt MS, Ogden CL. Racial and ethnic differences in weight management behavior by weight perception status. Ethnicity & disease. 2010;20(3):244–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang VW, Christakis NA. Self-perception of weight appropriateness in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(4):332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00020-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuchler F, Variyam JN. Mistakes were made: Misperception as a barrier to reducing obesity. Int J Obes. 2003;27:856–861. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yancey AK, Simon PA, McCarthy WJ, et al. Ethnic and sex variations in overweight self-perception: Relationship to sedentariness. Obes. 2006;14(6):980–988. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JW, Brancati FL, Yeh HC. Trends in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Asians versus whites: results from the United States National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2008. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:353–357. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bender M, Choi J, Arai S, Paul S, Gonzalez P, Fukuoka Y. Digital technology ownership, usage, and factors predicting downloading health apps among Caucasian, Filipino, Korean, and Latino Americans - DiLH Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research mHealth and uHealth. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3710. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuoka Y, Bender M, Choi J, Gonzalez P, Arai S. Gender Differences in Lay Knowledge of Type 2 Diabetes Symptoms among Community-dwelling Caucasian, Latino, Filipino, and Korean Adults, Diabetes Educator. doi: 10.1177/0145721714550693. Accepted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in cooperation with The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. 1998 Sep; The Evidence Report. NIH Publication no 98-4083. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, Kaufman FR, Palinkas LA, Rosenbloom AL, Schwimmer JB. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment: a consensus statement of Shaping America. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2211–21. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim H, Wang Y. Body weight misperception patterns and their association with health-related factors among adolescents in South Korea. Obes. 2013;21:2596–2603. doi: 10.1002/oby.20361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardle J, Haase A, Steptoe A. Body image and weight control in young adults: International comparisons in university students from 22 countries. Int J Obes. 2006;30:644–651. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.USDHHS. Overweight and Obesity Statistics. NIH Publication No. 04–4158 Updated October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowman RL, DeLucia JL. Accuracy of self-reported weight: a meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1992;23:637–655. [Google Scholar]