Abstract

Water-mediated hydrogen exchange (HX) processes involving the protein main chain are sensitive to structural dynamics and molecular interactions. Measuring deuterium uptake in amide bonds provides information on conformational states, structural transitions and binding events. Increasingly, deuterium levels are measured by mass spectrometry (MS) from proteolytically generated peptide fragments of large molecular systems. However, this bottom-up method has limited spectral capacity and requires a burdensome manual validation exercise, both of which restrict analysis of protein systems to generally less than 150 kDa. In this study, we present a bottom-up HX-MS2 method that improves peptide identification rates, localizes high-quality HX data and simplifies validation. The method combines a new peptide scoring algorithm (WUF, weighted unique fragment) with data-independent acquisition of peptide fragmentation data. Scoring incorporates the validation process and emphasizes identification accuracy. The HX-MS2 method is illustrated using data from a conformational analysis of microtubules treated with dimeric kinesin MCAK. When compared to a conventional Mascot-driven HX-MS method, HX-MS2 produces two-fold higher α/β-tubulin sequence depth at a peptide utilization rate of 74%. A Mascot approach delivers a utilization rate of 44%. The WUF score can be constrained by false utilization rate (FUR) calculations to return utilization values exceeding 90% without serious data loss, indicating that automated validation should be possible. The HX-MS2 data confirm that N-terminal MCAK domains anchor kinesin force generation in kinesin-mediated depolymerization, while the C-terminal tails regulate MCAK-tubulin interactions.

Keywords: hydrogen/deuterium exchange, mass spectrometry, data independent acquisition, new algorithms, software, microtubules, kinesin

Introduction

Solvent-mediated hydrogen exchange (HX) is a useful tool for studying local and global conformational dynamics of proteins. When used carefully, the HX method can map protein interactions interfaces, chart mechanisms of allosteric regulation, and shed light on fundamental properties of protein folding. Historically HX has been wielded by NMR spectroscopists but with the advent of NMR methods for high-resolution analysis, HX has slowly faded in significance. Mass spectrometry (MS) has sparked a resurgence, and in some cases a re-learning, of the HX method. A growing number of studies incorporate HX-MS into biophysical analyses of protein folding,1,2 protein-ligand interactions,3,4 membrane protein dynamics5,6 and therapeutic antibody characterization.7 MS should open many new frontiers. Fast detection holds the promise of improved temporal resolution,8 and MS is not burdened by the same molecular weight and composition limits of the NMR routine.

Most HX-MS studies incorporate bottom-up LC-MS methods borrowed from proteomics, where peptides provide the deuteration data.9 Proteins are digested with acid-stable non-specific proteases. Peptides are identified by LC-MS2, and each peptide is monitored in the HX-MS labeling experiments. While bottom-up methods should permit ultra-large protein characterization by HX, this promise has yet to be realized. Label back-exchange imposes a serious restraint on data collection, by enforcing an LC workflow restricted to short analysis times. This back-exchange restraint leads to spectral overlap, ion suppression, and a burdensome manual validation of isotopic distributions selected for deuteration calculations. Even with the sophisticated software tools available for HX-MS, practitioners of the bottom-up method spend most of their time in manual analysis of peptide isotopic profiles.10 The problem becomes acute when projects involve replicate kinetics analyses, swelling the number of runs into the 10–100 range.

We previously showed that peptide fragments generated using MS2 provide surrogate measures of peptide deuteration, and increase the capacity of the basic HX-MS method.11,12 Software was developed to quantify deuteration levels in both MS and MS2 datasets sufficient to illustrate the utility of HX-MS2.13 In the exercise, we noticed a disconnect between the number of peptides identifiable using proteomic database search tools, and the number of peptides ultimately useable for HX measurements. Greater than 50% of the peptides identified were unsuitable for supporting deuteration measurements. In addition, many peptide features that seemed suitable for HX were not identified, an observation that was also made recently by Englander et al.14,15

The current study addresses whether the peptides generated in a bottom-up HX-MS workflow are being mined effectively for exchange analysis. In most HX-MS experiments, the contents of the sample are known and the number of proteins is usually modest, even when interrogating large multi-protein systems. This scenario is considerably different than a proteomics analysis, where the sample contents are not known, and where the sample composition is much more complex. Our use of informatics strategies borrowed from proteomics may not be appropriate. Here, we implement and optimize a data-independent acquisition (DIA) method for collecting comprehensive HX-MS2 data. The new approach is applied to a protein complex consisting of microtubules (MTs) saturated with the depolymerizing mitotic centromere-associated kinesin (MCAK).16 MCAK is a member of the Kinesin-13 family, which acts to depolymerize MTs during mitosis.17 Depolymerization is accomplished by active removal of α/β-tubulin through a conformational transition. MCAK engages the MT lattice and diffuses to the plus-end where depolymerization is initiated, in concert with a nucleotide cycling event.18 Drug-stabilized MTs resist depolymerization and can be used to capture intermediate states of depolymerization.19,20 Our previous study suggested that dimeric MCAK straddles MT protofilaments and induces lattice strain along both longitudinal and lateral axes.21 The study suggested independent roles for the N-terminal (residues 1–185) and C-terminal (residues 584–718) domains. Aided by N-terminal and C-terminal deletions, we clarify the role of MCAK termini in the MT depolymerization process, using the HX-MS2 method. New strategies for scoring peptide identifications are presented and evaluated through this protein system. Results are compared to conventional HX-MS data on the same protein system.

Results

Optimizing DIA HX-ms2 for HX measurements

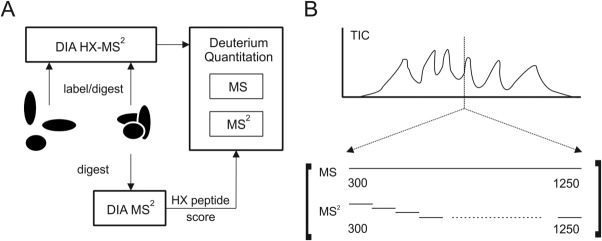

DIA methods provide an opportunity to collect peptide deuteration values in both the MS and MS/MS domains, by relying on fast fragmentation to generate sequence data across the entire mass range, and at a rate sufficient to support the chromatographic timescale.22 DIA methods for HX can blend identification and deuteration activities in each run (Fig. 1). The DIA dataset contains peptide fragments that align with the retention time of precursor ions, and the alignment establishes sequence identity and the presence of the peptide. Deuteration data can then be measured from the precursor ions for conventional HX-MS, but also from the fragments provided they have suitable ion statistics.

Figure 1.

The data-independent acquisition (DIA) of peptide fragment data built into the HX method for DIA HX-MS2. (A) The DIA method is applied to an unlabeled digest and used to generate a peptide list characterized by uniqueness and maximum utility for HX measurements. The peptides are then monitored in the full set of labeling experiments. Computational routines support an extraction of HX values from a combination of the best MS and MS2 data. (B) DIA provides a full complement of fragmentation spectra by fast sequential binning of the mass range.

We developed a DIA method around the compositional complexity presented by the MT-MCAK interaction. The interaction involves the α/β-tubulin dimer (110kDa) and a C-terminally deleted MCAK construct (ΔCT1-583, 65kDa), presenting ∼175 kDa of unique sequence, and an assembled state that exceeds 1 GDa (Supporting Information Fig. S1). We digested the complex using non-specific acid proteases to create a large pool of peptides.

We first tuned peptide ion transmission and collision energies on series of peptide standards for the QTOF mass spectrometer used in this work (Materials and Methods, and Supporting Information Fig. S2). In both pattern and S/N levels, fragmentation was comparable to peptides collected using the conventional data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. We then adjusted the fragmentation bin sizes, to achieve an even distribution of peptides across the m/z range. The adjustment created conditions under which fragment densities in each bin were roughly comparable (not shown), with bin sizes ranging from 25 to 40 Th.

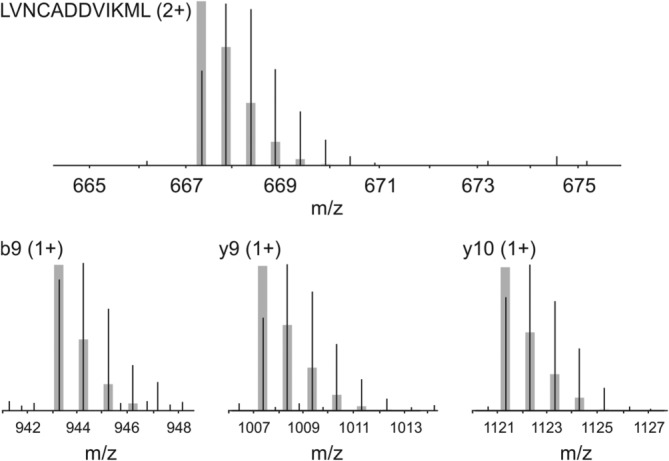

An HX-DIA method adds two additional complexities to the optimization exercise. The first involves deuterium randomization within the peptides. Deuterium should be “scrambled” throughout the sequence for a peptide fragment to function as a useful peptide surrogate.11 Fortunately, scrambling is the normal condition during high-efficiency ion transmission and collisionally induced dissociation (CID).23 We confirmed complete scrambling under our optimized settings using peptide HHHHHHIIKIIK (Supporting Information Fig. S3), a sequence designed to quantify MS-induced deuterium randomization.24 Mass Spec Studio software also tests more broadly for scrambling. In peptides where both MS and fragment deuteration data are available, fragment deuteration levels are calculated and compared to the real data. We inspected hundreds of peptides and have not observed a significant deviation from the scrambled state (not shown). The utility of peptide surrogacy was confirmed with a peptide from a region of MCAK that becomes protected upon binding to MTs (Fig. 2). Deuterated b and y ions were used to calculate the peptide's deuterium level, after correcting for the fraction of exchangeable hydrogens in the fragment. Deuteration values are generally consistent between the fragments and the peptide precursor, and fragments provide a sensitive measure of differences in deuteration when they are sufficiently intense (Table1).

Figure 2.

Peptide surrogacy using MS2 fragments. Isotopic profile of deuterated ΔCT-MCAK peptide LVNCADDVIKML and three fragments, representing the unbound state. Deuteration is evident by comparing the actual profiles to the calculated non-deuterated distributions, shown in gray.

Table 1.

Deuteration Values from Parent Peptide and Sequence Fragments as Surrogates

| %D complexa | %D freea | ΔD | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVNCADDVIKML (2+)b | 17.5 (0.6) | 25.2 (1.1) | −7.7 | 0 |

| y11 (1+) | 15.1 (3.8) | 28.4 (2.6) | −13.3 | 0.00 |

| y10 (1+) | 19.3 (0.6) | 26.1 (1.2) | −6.8 | 0.00 |

| y9 (1+) | 18.5 (1.8) | 25.7 (1.0) | −7.2 | 0.00 |

| y8 (1+) | 17.1 (2.0) | 25.8 (2.6) | −8.7 | 0.00 |

| y7 (1+) | 23.3 (1.6) | 26.3 (2.0) | −3.0 | 0.04 |

| b9 (1+)ML | 19.8 (2.5) | 26.3 (1.7) | −6.5 | 0.01 |

| b8(1+)IKML | 21.6 (3.7) | 26.6 (2.2) | −5.0 | 0.07 |

| b7 (1+)VIKML | 22.5 (1.2) | 26.6 (2.4) | −4.1 | 0.02 |

Value (std. dev.) in percentage of maximum peptide deuteration.

Peptide or sequence fragment (charge states).

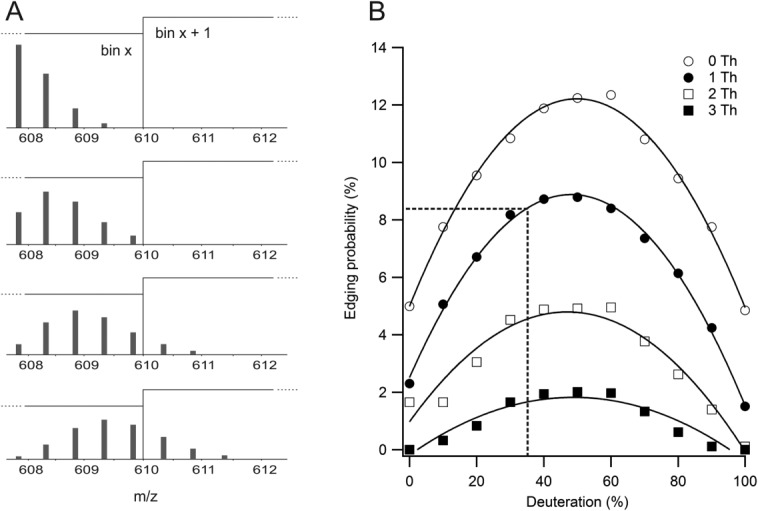

The second complexity introduced by DIA involves mass bin switching upon deuteration. Variable peptide deuteration in the course of an experiment can move an isotopic distribution from one bin into another [Fig. 3(A)]. This creates an edging effect, where the ion transmission windows can bisect a distribution. Edging would mean the data is only useable in the MS domain, and not the MS2. We modeled the severity of the effect using a library of 2800 peptides, with properties that represent a typical bottom-up HX experiment (5–27 amino acids in length, 12.5 amino acids average length), and explored the frequency of edging as a function of deuterium levels [Fig. 3(B)]. Our analysis shows that isotope expansion increases the frequency of edging, which can be rescued by overlapping the bins. However, mass bin overlap means more bins are needed, which in turn lengthens the cycle time and negatively impacts the effectiveness of DIA. We considered a 1Th overlap to be acceptable, and implemented a lower percentage of D2O in the labeling experiment (35%). The conditions generated a cycle time of 2.4 s.

Figure 3.

Mass binning can bisect isotopic distributions in a deuteration-dependent manner. (A) Edges of a given mass bin, here indicated by the vertical line, can exert a variable effect on a changing deuteration pattern. A peptide affected by bin edges can be useable in MS space but will have perturbed deuteration values in MS2 space. (B) Edging probability is a function of percent D2O applied, and can be minimized by overlapping bins. The black box marks the conditions used in this study (35% D2O, 1 Th overlap) and an estimate of the maximum data loss resulting from edging effects.

Peptide inventories

Feature identification for HX-MS

Peptide identification for HX-MS typically involves DDA applied to undeuterated digests, and then a database search on the output using Mascot, Sequest or some other database search engine. Because non-specific proteases are used, a restricted database containing only the expected proteins is created to improve search conditions. We applied DDA to the undeuterated proteolytic digestion of α/β-tubulin plus MCAK, to mimic the usual approach to HX-MS where peptide lists are first generated on the proteins to be characterized. The experiment was repeated and the identification lists combined, to ensure complete sampling. With this approach, we found 340 peptide features for α/β-tubulin. We then tested the tubulin peptide list on HX-MS2 data, collected for the MT-ΔCT interaction. Only the LC-MS data in the runs were interrogated with the peptide list, to match a typical HX-MS experiment. Of the 340 identified peptides, only 151 (44%) were found to be useful in HX measurements and present in at least 75% of the replicates. To be useful, we required an isotopic profile to be free of overlap, and of sufficient intensity to generate an expected isotopic distribution.

HX-tuned scoring functions

We then developed scoring functions for DIA data to test if we could improve identification rates and better support the manner in which HX data is used. Scoring algorithms and search strategies in shotgun proteomics generate identifications that subscribe to a principle of parsimony, returning the single-best sequence for a given MS2 spectrum (e.g., Ref.25). The handling of chimeric MS2 spectra—where two or more peptides selected in MS space generate overlapping fragmentation patterns—is a problem that becomes particularly acute in DIA HX-MS2. Large transmission windows, short LC run-times, and nonspecific digestion can lead to highly complex fragment space. Deuteration measurements should require that a selected isotopic profile is unique to a single sequence, because it is used to measure a biophysical property of a specific region in a protein. As digest complexity increases, a parsimonious scoring strategy may not correlate with uniqueness.

We first implemented a variant of the X!Tandem hyperscore function, the basic form of which is shown in Eq. 1.26,27 A library of all possible peptides of 3–25 residues was used to generate ion chromatograms in both the MS and MS2 space. Features were aligned, and then the fragment chromatograms were marked for uniqueness in the respective DIA mass bin. That is, a given mass bin was assessed for the peptides that could theoretically be present based on the peaks that were detected at that point in the chromatogram, and these were used to evaluate fragment uniqueness in the corresponding MS2 data. Peptides were scored using only unique fragment ions according to Eq. 1,

| 1 |

where Ii is the intensity for unique fragment i, normalized to the total fragment intensity, Nb is the number of unique b ions and Ny the number of unique y ions. If any of the sequence ions also exhibit unique neutral loss equivalents, they are included in the counts as well as well.

We previously showed that larger fragment ions are more reliable as surrogates in HX-MS2.12 High intensity fragments are also more likely to generate useful isotopic distributions for HX measurement. We devised a score that combined the identification of unique fragments with these observations [Eq. 2]:

| 2 |

where

and

to generate a weighted unique fragment (WUF) score. In the first sum, g is a sigmoidal function that scales unique fragment intensities Ii based on a slope parameter s, and a benchmark intensity value b. The sum is log transformed to avoid suppressing the identification power of the second sum. In this second sum, relative fragment lengths Fi are weighted with a rectangular hyperbolic function h, where Lp is the length of the peptide in amino acid residues, Li the length of the fragment in amino acid residues and a is a slope parameter. Here, fragments are unique b ions and y ions, as well as the unique neutral loss equivalents.

High fidelity isotopic distributions are desirable for precise HX measurements, so intensity scaling seeks to capture the idea that—below a certain value—two fragments of x intensity are not as useful in HX as one fragment of 2x intensity (g function). Similarly, we reasoned that isotopic distributions of low mass fragments would not generate a wide dynamic range of deuteration, thus two fragments of y length should not be scored the same as one fragment of 2y length. The proposed WUF score blends these two concepts with an identification that is based on the summation of unique fragment lengths.

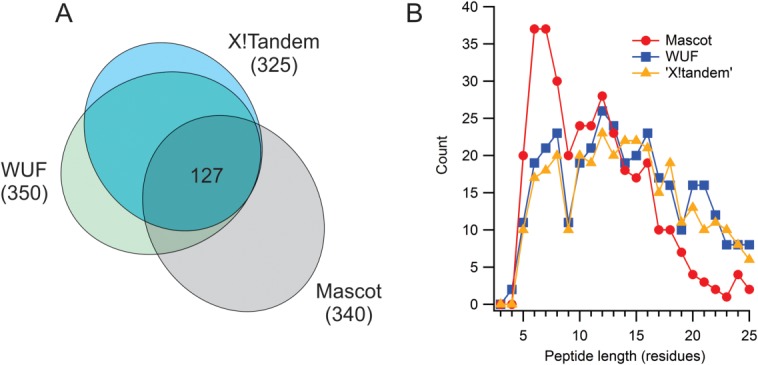

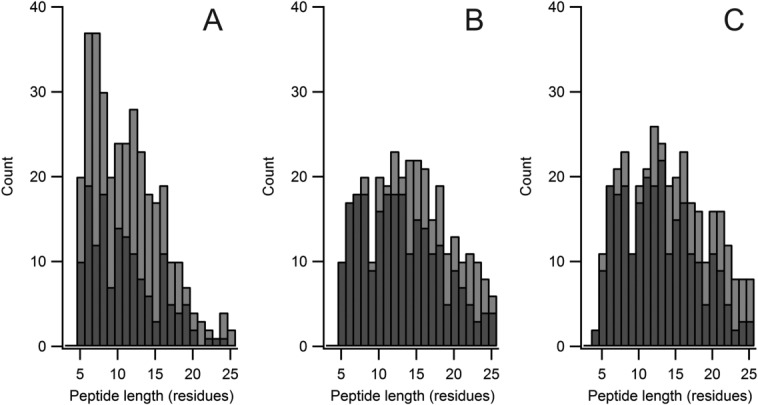

The hyperscore generated an extensive number of tubulin hits when applied to the unlabeled DIA data, slightly less than the number returned by the Mascot search on the DDA dataset, but clearly not fully intersecting (Fig. 4). The Mascot search was more strongly biased to smaller peptides than the hyperscore. It would be unfortunate to lose information on smaller peptides in an HX analysis, since short peptides convey higher structural resolution. We evaluated the hit set manually, to determine which tubulin peptides were useable for HX analysis in either MS or MS2 space. Similar to the Mascot validation exercise, a peptide was considered useable if the selected isotopic profile was free of overlap, and of sufficient intensity to generate a well-formed isotopic distribution. (The isotopic profile could reside in either MS or MS2 space, however.) The isotopic profile was required to be present in both bound and free states and in at least 75% of the replicates. The hyperscore returned a high percentage of useful hits (242 of 325, or 75%) compared to Mascot (151 of 340, or 44%) but without losing a meaningful fraction of short peptides (Fig. 5). In other words, the failure rate of Mascot is higher for the intended use, and more notably so for shorter peptides.

Figure 4.

Comparison of peptide scoring algorithms. (A) Intersection of peptide identifications for Mascot (applied to DDA data, P < 0.05), X!Tandem hyperscore (calculated from unique fragments in DIA data, FUR of 0.5%), and WUF score (from DIA data, FUR of 0.5%). (B) Distribution of hits as a function of peptide length, using the criteria as in (A).

Figure 5.

Distribution of validated hits compared to total hits, on length basis, for (A) Mascot (B) X!Tandem hyperscore on unique fragments and (C) WUF score. Hit lists as in Figure 4, and peptides validated against eight DIA HX-MS2 runs, using criteria described in the text. Total hits in light gray, validated hits in dark gray.

The WUF score generated a response incrementally better than the modified hyperscore. Figure 4 shows only minor differences in the total number of hits, and in the size distribution of the hits. The utilization rates are also similar (258 of 350, or 74%) (Fig. 5). Again, these utilization rates are high relative to Mascot. For either WUF or X!Tandem-unique, utilization rates can be increased substantially by adjusting the false utilization rate (FUR) associated with the scoring methods. FUR is calculated like a false discovery rate, and relies on the decoy database approach.28 For example, a WUF score with a FUR reduced from 0.5% to 0.1% returns a 91% utilization rate (162 of 178), with coverage that is superior to the Mascot-driven HX-MS approach.

To incorporate poorly fragmenting but otherwise abundant peptides in the pool of useable HX features, we included unique MS feature detection as an option in the WUF scoring approach. Peaks were detected in the ion chromatograms for all possible peptides produced by a nonspecific digest. Unfortunately, while many features were found that were not otherwise identified by MS2 data, most were either overlapped at the resolution of the instrument, nonredundant in sequence, or of poor ion statistics to be useful for HX. Only three peptides could be identified based on uniqueness in the MS domain.

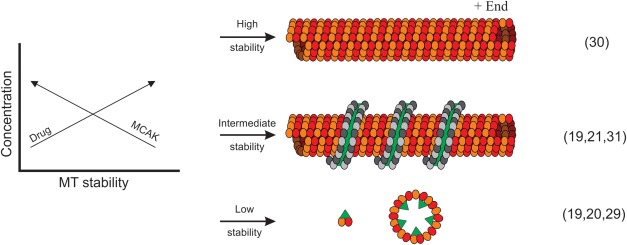

MCAK-MT interaction analysis by DIA HX-MS2

The optimized DIA method based on WUF scoring was then applied to a conformational analysis of MCAK deletion constructs bound to MTs, specifically to confirm how the N-terminal and C-terminal domains contribute to the generation of MT depolymerization force. Dimeric MCAK diffuses to the plus-end of a microtubule and undergoes a nucleotide-driven conformational change likely involving both longitudinal and lateral force components.18,21 Force generation imparts outward strain on the MT lattice and peels away tubulin protofilaments from the lattice. Drugs in the taxoid class stabilize MTs and oppose this potent depolymerization force, providing an opportunity to increase the MCAK load on the MTs and capture a stable depolymerized state (Fig. 6). Using this approach we described a model of MT depolymerization where dimerized MCAK straddles two parallel protofilaments. Upon nucleotide exchange to the ATP-loaded state, paired MT protofilaments are pulled outward and twisted.21

Figure 6.

Developing a testable representation of MCAK-driven MT depolymerization for HX. Drug-stabilized MTs are resistant to MCAK-induced destabilization, allowing for higher MCAK loading on the lattice to compensate. An intermediate state can be formed where residual MTs capture depolymerizing protofilament polymers as windings around the lattice. The lattice-bound captured protofilaments are efficiently isolated by centrifugation. Depolymerized protofilaments of α/β tubulin are shown (dark and light gray circles) captured on an MT lattice (yellow and orange circles). MCAK is shown in green. Citations in brackets provide additional details regarding the preparation and characteristics of the states.

Our previous analysis did not fully resolve the roles of the N and C termini in the depolymerization process. To test our model and shed light on the function of the termini, we induced MT depolymerization with full-length MCAK and a C-terminal MCAK deletion (ΔCT1-583). The HX-MS2 method was applied to both complexes, as well as the individual states (MTs, FL-MCAK, ΔCT-MCAK). Binding assays and electron microscopy confirmed the capture of the depolymerized state on microtubule templates for both full-length and ΔCT MCAK (Supporting Information Fig. S1). Sequence coverage was substantially improved for all protein states under HX-MS2 conditions, compared to the HX-MS approach alone (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

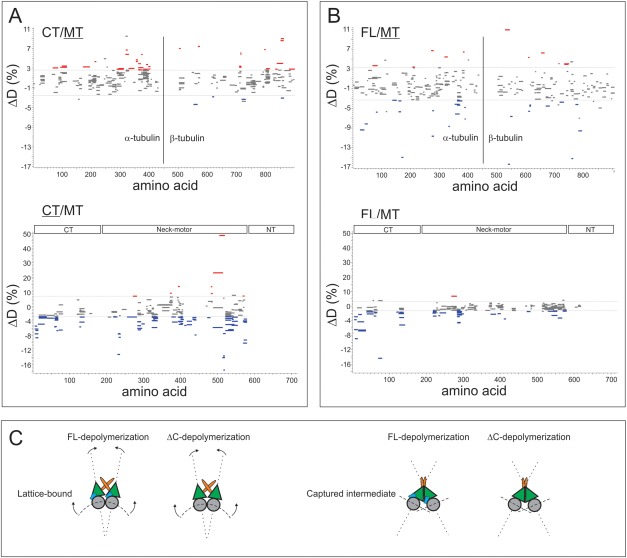

Deleting the CT domain from MCAK does not appear to influence the conformational state of the MCAK N-terminal domain (Fig. 7). It remains stabilized upon depolymerization and capture, similar to what we observe with full-length MCAK. The EM data confirm that the deletion still permits protofilament windings around the template MTs as modeled in Figure 6. These windings are indistinguishable from the ones we see with full length MCAK (Supporting Information Fig. S1), although the ΔCT windings occasionally transition to a thinner state, with lower periodicity. An ΔNT MCAK construct did not generate any ribbon windings (Supporting Information Fig. S1), and appears to behave similarly to the monomeric neck-motor domain in this regard (not shown). Together, these data support that windings are a property of dimeric MCAK under the depolymerization-resistant conditions we developed for the study. The N-termini are required for dimerization, and for anchoring the extra lateral force needed to depolymerize the drug-stabilized MT state.

Figure 7.

Woods plots assembled using validated DIA HX-MS2 data from the WUF scoring approach (FUR of 0.5%), applied to (A) an analysis of ΔCT-MCAK depolymerizing MTs (CT/MT) and (B) an analysis of full length MCAK depolymerizing MTs (FL/MT). The plots represent HX values for the depolymerized and captured state relative to the free state, for the underlined protein. Blue represents a stabilization upon depolymerization and capture, and red a destabilization. Horizontal lines in plots denote ±2 SD cut-off determined from noise in the ΔD measurements, and gray segments represent peptides with P > 0.05 from replicate analysis. Positions of the segments indicate location in protein sequence. (C) HX analysis together with EM data support a model that involves a dimerized MCAK (green motor units) generating lateral force through N-terminal (orange) domains, whereas the C-terminal (blue) domains regulate tubulin binding and release. In the absence of the C-terminal domains, the tubulin-MCAK interaction is proposed to be weakened.

In addition, removing the C-terminal tail destabilized the motor domain but this was strongly reversed upon depolymerization [Fig. 7(A)]. Our previous study pointed to a role for the C-terminal tail in regulating the MT interaction through the motor domain, which is consistent with our new data. It suggests that the C-terminal tail needs to be “dislocated” from the motor prior to full engagement of the motor on the MT lattice.

Interestingly, the CT deletion construct does not stabilize the captured MT windings as well as FL-MCAK. Longitudinal destabilizations are consistent with an outwardly-curved protofilament, as each α/β-tubulin dimer reverts to a bent form.32–34 We observe these longitudinal destabilizations in the FL-MT state, however they are more extensive in ΔCT-MT and accompanied by additional destabilizations in the lateral protofilament surfaces (Fig. 7). Additionally the windings randomly transition from thick to thin around the MT template. We conclude that the C-terminus is required to stabilize MCAK-tubulin interactions. With this interpretation, the variable thickness of the windings represents the loss of parallel protofilament segments, because of weaker interactions between MCAK and its tubulin partners, likely because the motor domain adopts an alternative conformation in the absence of the C-terminal tail.

Discussion

The DIA HX-MS2 method described in this study allowed us to test our model of MCAK-driven microtubule depolymerization, which proposed that dimeric MCAK produces both longitudinal and lateral force on parallel paired protofilaments. The model only inferred a role for the NT and CT domains. Using new MCAK constructs, EM and HX-MS2, we show that MCAK dimerization requires the NT domains, and strong lattice engagement requires the CT domains. The new data are therefore consistent with our earlier model, and point to separable functions for the tail regions of MCAK: the NT for anchoring force generation in the dimer and the CT for regulating tubulin interaction and release.

The bottom-up strategy of data collection is currently the only viable means of HX data collection for ultra-large assemblies like the MT lattice. As protein complexity increases we see a significant drop in the effective sequence coverage provided by the basic HX-MS method. Large collections of peptides constrained to short run times lead to ion suppression and overlap. As we have shown, a conventional workflow does not effectively mine the peptides that are present. A simplified HX-MS2 method requires only one identification run on a non-deuterated digest, under conditions otherwise identical to the labeling experiments (e.g., runtime, temperature, digestion conditions). The peptide list extracted from the run can be confidently applied to the labeled runs. Using MS2 data for HX quantitation along with scoring functions that are based on unique mass signatures, we can recover substantially higher peptide identification and usage rates. Higher performance of this nature is based on a more effective use of sequence data, and this performance should scale well to protein systems of even greater size. The modified hyperscore and the WUF score generate similar performance, which probably indicates that unique fragment masses are of primary importance. Modifications of the WUF score strategy are worth evaluating to drive usage rates even higher, and will be the subject of future work in this area. We note that excessively high percentages of D2O in the labeling experiment may weaken the current version of the identification algorithms. Higher D2O levels could lead to more extensive fragment overlap in MS2 space. Overlap detection can be applied in subsequent versions of the algorithm, but we note that high percentages of D2O are not usually needed in HX-MS.35 Overall, the DIA-based method can be implemented at minimal cost, because the MS data is still available for use.

The HX-MS2 data in this study raise a number of issues for the bottom-up method, which need to be considered when analyzing ever-larger complexes:

Peptide misidentification

MS-only HX data can be allocated to the wrong peptide. The frequency of fully-overlapped isotopic distributions grows with sample complexity, generating chimeric MS2 spectra. In the worst case, completely different regions of structure can be assigned when adopting typical proteomics identification strategies. A unique MS2 surrogate should be used in such cases, or the peptide rejected.

Unallocated peptide features

Although a large number features in LC-MS are not attributed to peptide sequences, it is unwise to use accurate mass unless the sample composition is fully known. Even with TOF and Orbitrap mass accuracies, the opportunity for capturing this unused pool on the basis of mass alone drops to negligible levels, with increasing protein molecular weight. Other fragmentation methods, and perhaps retention time prediction, may rescue a fraction of this pool.

Validating peptides for HX

Positive peptide identification and utility for HX do not necessarily correlate. Identification algorithms built around uniqueness and detectability are needed, to at least reduce the validation effort required for ultralarge systems. Scoring routines such as WUF essentially provide a validation score. A FUR determination provides a filter that can be selected based on the amount of coverage needed, and the validation effort willing to be undertaken.

Digestion restrictions

Variable digestion is one reason why peptides drop off the validated list. That is, a digestion routine for a single protein cannot be expected to generate an identical group of peptides when additional proteins are added. Large systems analysis will require careful digestion optimization as a result, and the problem will remain until an enzyme is found that generates complete digestion on the HX timescale.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals, reagents, and proteins

All synthetic peptides were purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). Bovine brain tubulin (99% pure, cat#TL238) was purchased from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO). GMPCPP purchased from Jena Biosciences (Jena Germany), ATP and Taxotere from Sigma. MCAK deletion constructs were expressed and purified as previously described.

Feature identification—DDA

Peptide feature identifications were made in the conventional manner. Briefly, proteins were digested under HX conditions and constraints (2.5 min digestion using nepenthes fluid concentrate at 10°C) and injected into an LC-MS2 system. We used an AB Sciex TripleTOF 5600 configured with an Eksigent Ultra 2D pump. Peptides were captured on a 250 μm ID × 15 mm C18 trap column and separated on a 200 μm ID × 70 mm C18 column, prepared in-house. A 10 min gradient (15–40% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid) was used to separate peptides, at a flow rate of 4 μL min−1. The LC system temperature was held at 4°C, in the HDX PAL module associated with the LC-MS system. For DDA analysis, MS/MS spectra were obtained from a single typical gradient run, and then repeated with a gradient three times as long, for comparison. Spectra were searched against a customized database containing multiple isoforms of bovine tubulin, and full length MCAK using MASCOT v2.4. A 10 ppm mass tolerance and P < 0.05 probability score cut-off were applied, with no enzyme specificity declared. No amino acid modifications were included.

DIA optimization

DIA optimization was performed using Sequential Windowed Acquisition of all THeoretical fragment ion mass spectra (SWATH™) on the AB Sciex TripleTOF 5600 by direct infusion of a solution containing 11 peptides, and compared to optimized product ion scans for each peptide. The declustering potential (DP) and the collision energy (CE) was selected for SWATH bins such that comparable fragmentation spectra were observed in each scan type. Fragment acquisition time in both modes was 100 ms. The impact of bins on bisection of isotope profiles was evaluated by simulations using identified peptides from nine different proteins from different projects (2,800 peptides). A peptide was classified as “edged” if 2% or more of the profile intensity occupied a second bin.

Protein complex reconstitution and HX labeling

The MCAK-MT complexes were generated and characterized as previously described.21 Briefly, doubly-stabilized microtubules were formed in assembly buffer (10 mM PIPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 100 mM KCl, pH 6.9). Stabilization was achieved using GMPCPP (1 mM) and taxotere (50 μM). MCAK constructs were added to microtubules and incubated at 37°C for 10 min to allow MCAK binding and depolymerization. Microtubules with bound MCAK were pelleted via centrifugation, and the excess MCAK and non-polymerized tubulin in the supernatant were removed. For HX experiments, the pellet was gently re-suspended in assembly buffer made from D2O for a final D2O concentration of 35%. Samples were labeled for 300 s. Labeling was quenched and digestion conducted at 10°C for 2.5 min by addition of 2 µL nepenthes fluid concentrate (in 100 mM glycine-HCl, 4 mM CaCl2, pH 2.35). The sample was injected into the LC-MS for HX analysis.

DIA for identification and HX-ms2

Using the gradient conditions and LC-MS described above, together with an HDX PAL autosampler to manage replicate analysis, a series of runs were performed. The only difference between the runs for identification and HX analyses involved D2O. For identification, the complexed samples (MCAK + MT) were diluted with unlabeled water, and with D2O for the HX runs. The mass spectrometer was operated in the optimized SWATH-acquisition mode. Each cycle was comprised of one MS scan (300–1250 m/z) accumulated for 250 ms, followed by 23 variable m/z bins spanning an m/z range of 300–1000, accumulated for 100 ms each.

DIA HX-ms2 data analysis

All data processing was conducted in Version 1.3.0 of Mass Spec Studio, which presents several enhancements to the previous HX-MS2 method described.13 First, project creation is simplified for any kind of HX experiment (MS only, DDA or DIA). Second, the DIA HX-MS2 method is now split into two stages: identification and HX quantification. The new peptide identification method, which includes the WUF score, requires undeuterated runs and can process both DIA and DDA data. The HX quantification method uses information from the identification run to apply custom filtering rules to the identified peptides before the manual validation stage. Finally, several overall performance improvements of the new method allows larger protein systems to be processed faster than the original version (see http://server.sams.ucalgary.ca/downloads/for software). For the scoring results, an FUR of 0.5% was applied unless otherwise specified. Deuteration levels were reported using MS domain data, unless overlap or low intensity spectra required the MS/MS domain. No back-exchange correction was applied. Validation procedures are described in main text. Standard deviations were determined from quadruplicate analysis, on a per peptide basis. Differential labeling between bound and unbound states was reported as significant if it passed two criteria: a pooled two-tailed t test for the individual peptide (P < 0.05) and a ΔD greater than two standard deviations of all the data with P > 0.05.

Glossary

- CID

collisionally induced dissociation

- DDA

data dependent acquisition

- DIA

data independent acquisition

- FUR

false utilization rate

- HX

hydrogen exchange

- MCAK

mitotic centromere associated kinesin

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS2

tandem mass spectrometry

- MT

microtubule

- SWATH™

sequential windowed acquisition of all theoretical fragment ion mass spectra

- WUF

weighted unique fragment

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Supporting Information Figure 1.

Supporting Information Figure 2.

Supporting Information Figure 3.

Supporting Information Figure 4A.

Supporting Information Figure 4B.

References

- Khanal A, Pan Y, Brown LS, Konermann L. Pulsed hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry for time-resolved membrane protein folding studies. J Mass Spectrom. 2012;47:1620–1626. doi: 10.1002/jms.3127. PMID: 23280751 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WB, Walters BT, Kan ZY, Mayne L, Rosen LE, Marqusee S, Englander SW. Stepwise protein folding at near amino acid resolution by hydrogen exchange and mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7684–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305887110. PMID: ISI:000319327700045 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MJ, Barakat K, Huzil JT, Tuszynski J, Schriemer DC. Discovery and characterization of the laulimalide-microtubule binding mode by mass shift perturbation mapping. Chem Biol. 2010;17:725–734. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.019. PMID: 20659685 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West GM, Willard FS, Sloop KW, Showalter AD, Pascal BD, Griffin PR. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor ligand interactions: structural cross talk between ligands and the extracellular domain. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105683–25180755. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105683. PMID: {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey M, Man P, Clemencon B, Trezeguet V, Brandolin G, Forest E, Pelosi L. Conformational dynamics of the bovine mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier isoform 1 revealed by hydrogen/deuterium exchange coupled to mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34981–34990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146209. PMID: 20805227 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore CS, Wood TJ, Beavis AW, Saunderson JR. Correlation of the clinical and physical image quality in chest radiography for average adults with a computed radiography imaging system. Br J Radiol. 2013;86:20130077. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20130077. PMID: 23568362 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei H, Mo J, Tao L, Russell RJ, Tymiak AA, Chen G, Iacob RE, Engen JR. Hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry for probing higher order structure of protein therapeutics: methodology and applications. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.019. PMID: 23928097 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami D, Devarakonda S, Chalmers MJ, Pascal BD, Spiegelman BM, Griffin PR. Time window expansion for HDX analysis of an intrinsically disordered protein. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2013;24:1584–1592. doi: 10.1007/s13361-013-0669-y. PMID: 23884631 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcsisin SR, Engen JR. Hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry: what is it and what can it tell us? Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;397:967–972. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3556-4. PMID: 20195578 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wales TE, Eggertson MJ, Engen JR. Considerations in the analysis of hydrogen exchange mass spectrometry data. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1007:263–288. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-392-3_11. PMID: 23666730 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy AJ, Slysz GW, Schriemer DC. Surrogate H/D detection strategy for protein conformational analysis using MS/MS data. Anal Chem. 2009;81:7900–7907. doi: 10.1021/ac901148u. PMID: 19681596 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy AJ, Schriemer DC. MRM methods for high precision shift measurements in H/DX-MS. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;302:26–35. PMID: ISI:000290693800005 {Medline} [Google Scholar]

- Rey M, Sarpe V, Burns KM, Buse J, Baker CA, van Dijk M, Wordeman L, Bonvin AM, Schriemer DC. Mass spec studio for integrative structural biology. Structure. 2014;22:1538–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.08.013. PMID: 25242457 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan ZY, Mayne L, Chetty PS, Englander SW. ExMS: data analysis for HX-MS experiments. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1906–1915. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0236-3. PMID: 21952778 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne L, Kan ZY, Chetty PS, Ricciuti A, Walters BT, Englander SW. Many overlapping peptides for protein hydrogen exchange experiments by the fragment separation-mass spectrometry method. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1898–1905. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0235-4. PMID: 21952777 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JR, Wagenbach M, Asbury CL, Wordeman L. Catalysis of the microtubule on-rate is the major parameter regulating the depolymerase activity of MCAK. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:77–82. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1728. PMID: 19966798 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wordeman L, Mitchison TJ. Identification and partial characterization of mitotic centromere-associated kinesin, a kinesin-related protein that associates with centromeres during mitosis. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:95–104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.1.95. PMID: 7822426 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel CT, Howard J. The kinesin-13 MCAK has an unconventional ATPase cycle adapted for microtubule depolymerization. EMBO J. 2011;30:3928–3939. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.290. PMID: ISI:000295967300008 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan D, Asenjo AB, Mennella V, Sharp DJ, Sosa H. Kinesin-13s form rings around microtubules. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:25–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605194. PMID: 17015621 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder AM, Glavis-Bloom A, Moores CA, Wagenbach M, Carragher B, Wordeman L, Milligan RA. A new model for binding of kinesin 13 to curved microtubule protofilaments. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:51–57. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812052. PMID: WOS:000265413200009 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns KM, Wagenbach M, Wordeman L, Schriemer DC. Nucleotide exchange in dimeric MCAK induces longitudinal and lateral stress at microtubule ends to support depolymerization. Structure. 2014;22:1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.06.010. PMID: 25066134 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JP, Ivosev G, Couzens AL, Larsen B, Taipale M, Lin ZY, Zhong Q, Lindquist S, Vidal M, Aebersold R, Pawson T, Bonner R, Tate S, Gingras AC. Mapping differential interactomes by affinity purification coupled with data-independent mass spectrometry acquisition. Nat Methods. 2013;10:1239–1245. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2702. PMID: 24162924 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand KD, Zehl M, Jorgensen TJ. Measuring the hydrogen/deuterium exchange of proteins at high spatial resolution by mass spectrometry: overcoming gas-phase hydrogen/deuterium scrambling. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47:3018–3027. doi: 10.1021/ar500194w. PMID: 25171396 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand KD, Jorgensen TJ. Development of a peptide probe for the occurrence of hydrogen (1H/2H) scrambling upon gas-phase fragmentation. Anal Chem. 2007;79:8686–8693. doi: 10.1021/ac0710782. PMID: 17935303 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geer LY, Markey SP, Kowalak JA, Wagner L, Xu M, Maynard DM, Yang X, Shi W, Bryant SH. Open mass spectrometry search algorithm. J Proteome Res. 2004;3:958–964. doi: 10.1021/pr0499491. PMID: 15473683 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R, Beavis RC. A method for reducing the time required to match protein sequences with tandem mass spectra. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2003;17:2310–2316. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1198. PMID: 14558131 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig R, Beavis RC. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1466–1467. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth092. PMID: 14976030 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. PMID: 17327847 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Verma S, Mitchison TJ, Walczak CE. Kin I kinesins are microtubule-destabilizing enzymes. Cell. 1999;96:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80960-5. PMID: 9989498 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzer KM, Ems-McClung SC, Kline-Smith SL, Lipkin TG, Gilbert SP, Walczak CE. Full-length dimeric MCAK is a more efficient microtubule depolymerase than minimal domain monomeric MCAK. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:700–710. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0821. PMID: 16291860 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Asenjo AB, Greenbaum M, Xie L, Sharp DJ, Sosa H. A second tubulin binding site on the Kinesin-13 motor head domain is important during mitosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73075. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073075. PMID: 24015286 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremichael Y, Chu JW, Voth GA. Intrinsic bending and structural rearrangement of tubulin dimer: molecular dynamics simulations and coarse-grained analysis. Biophys J. 2008;95:2487–2499. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.129072. PMID: 18515385 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MJ, Chik JK, Slysz GW, Luchko T, Tuszynski J, Sackett DL, Schriemer DC. Structural mass spectrometry of the alpha beta-tubulin dimer supports a revised model of microtubule assembly. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4858–4870. doi: 10.1021/bi900200q. PMID: 19388626 {Medline} [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asenjo AB, Chatterjee C, Tan D, DePaoli V, Rice WJ, Diaz-Avalos R, Silvestry M, Sosa H. Structural model for tubulin recognition and deformation by kinesin-13 microtubule depolymerases. Cell Rep. 2013;3:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.030. PMID: 23434508 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slysz GW, Percy AJ, Schriemer DC. Restraining expansion of the peak envelope in H/D exchange-MS and its application in detecting perturbations of protein structure/dynamics. Anal Chem. 2008;80:7004–7011. doi: 10.1021/ac800897q. PMID: 18707134 {Medline} [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information Figure 1.

Supporting Information Figure 2.

Supporting Information Figure 3.

Supporting Information Figure 4A.

Supporting Information Figure 4B.