Significance

In bacterial tRNAs with the 36GG37 sequence, where positions 36 and 37 are, respectively, the third letter of the anticodon and 3′ adjacent to the anticodon, the modification of N1-methylguanosine (m1G) at position 37 prevents +1 frameshifts on the ribosome. The m1G37 modification is introduced by the enzyme TrmD, which harbors a deep trefoil knot within the S-adenosyl-L-methionine (AdoMet)-binding site. We determined the crystal structure of the TrmD homodimer in complex with a substrate tRNA and an AdoMet analog. The structure revealed how TrmD, upon AdoMet binding in the trefoil knot, obtains the ability to bind the substrate tRNA, and interacts with G37 and G36 sequentially to transfer the methyl moiety of AdoMet to the N1 position of G37.

Keywords: RNA modification, SPOUT methyltransferase, TrmD, X-ray crystallography

Abstract

The deep trefoil knot architecture is unique to the SpoU and tRNA methyltransferase D (TrmD) (SPOUT) family of methyltransferases (MTases) in all three domains of life. In bacteria, TrmD catalyzes the N1-methylguanosine (m1G) modification at position 37 in transfer RNAs (tRNAs) with the 36GG37 sequence, using S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet) as the methyl donor. The m1G37-modified tRNA functions properly to prevent +1 frameshift errors on the ribosome. Here we report the crystal structure of the TrmD homodimer in complex with a substrate tRNA and an AdoMet analog. Our structural analysis revealed the mechanism by which TrmD binds the substrate tRNA in an AdoMet-dependent manner. The trefoil-knot center, which is structurally conserved among SPOUT MTases, accommodates the adenosine moiety of AdoMet by loosening/retightening of the knot. The TrmD-specific regions surrounding the trefoil knot recognize the methionine moiety of AdoMet, and thereby establish the entire TrmD structure for global interactions with tRNA and sequential and specific accommodations of G37 and G36, resulting in the synthesis of m1G37-tRNA.

It is highly exceptional for proteins to have a knot in their folding patterns. Actually, all of the proteins found to possess a deep trefoil knot (1–5) belong to a single family of RNA methyltransferases (MTases), named SPOUT after SpoU (currently called TrmH) and tRNA methyltransferase D (TrmD) (6). SPOUT MTases methylate the base or ribose moiety of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) or transfer RNA (tRNA) in all three domains of life. The deep trefoil knot of the SPOUT MTases provides the binding site for the methyl donor, S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet). The SPOUT MTase transfers the methyl moiety of AdoMet onto its substrate RNA, and produces the methylated RNA and S-adenosyl-l-homocysteine (AdoHcy). SPOUT MTases usually function as homodimers, although as an exception, yeast Trm10 functions as a monomer (7). In the homodimeric SPOUT MTases, the helix located at the carboxyl terminus of the deep trefoil knot is involved in the dimerization (1–5).

TrmD, the product of the trmD gene, is one of the broadly conserved SPOUT MTases in bacteria. It is responsible for the methylation at the N1 position of G37 in tRNA, in cases where the third anticodon letter, 5′ adjacent to G37, is also guanosine, G36 (Fig. 1A). The modified nucleotide N1-methylguanosine at position 37 (m1G37) is present in all three domains of life. Remarkably, mutations in trmD frequently result in growth defects, associated with increased +1 frameshift errors (8–12). Each TrmD monomer consists of two globular domains, the N-terminal domain (NTD), which harbors the SPOUT fold, called the “SPOUT domain,” and the TrmD-specific C-terminal domain (CTD) (Fig. S1A) (3, 5).

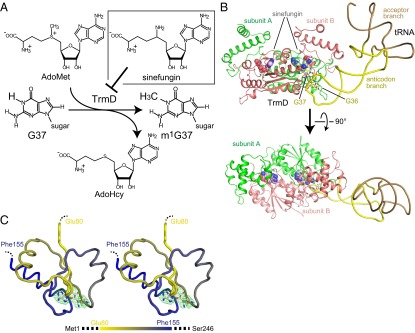

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of the TrmD•sinefungin•tRNA complex. (A) Schematic representation of the synthesis of m1G37-tRNA catalyzed by TrmD. The chemical structures of AdoMet, AdoHcy, and sinefungin are also shown. (B) Ribbon representation of the crystal structure of the ternary complex of TrmD, sinefungin, and tRNA. The TrmD subunits A and B are colored green and salmon, respectively. The acceptor and anticodon branches of tRNA are colored brown and yellow, respectively. G36 and G37 in the tRNA are represented by stick models. The sinefungin molecules in the AdoMet-binding sites of the TrmD subunits A and B are represented by CPK models, colored light green and light salmon, respectively. (C) The backbone wire model of the deep trefoil knot structure of subunit A in the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form of TrmD. The backbone model of the residues from Glu80 to Phe155 is presented in a stereoview, from the same angle as the lower panel of B. The color of the residues from Glu80 to Ala153 gradually changes from yellow to blue, to clarify the relationship between the positions in the primary structure and the knotted part in the tertiary structure, as in the bar indicated below. The bound sinefungin is represented by a stick model, and its simulated-annealing omit map, contoured at 3σ, is illustrated on the model.

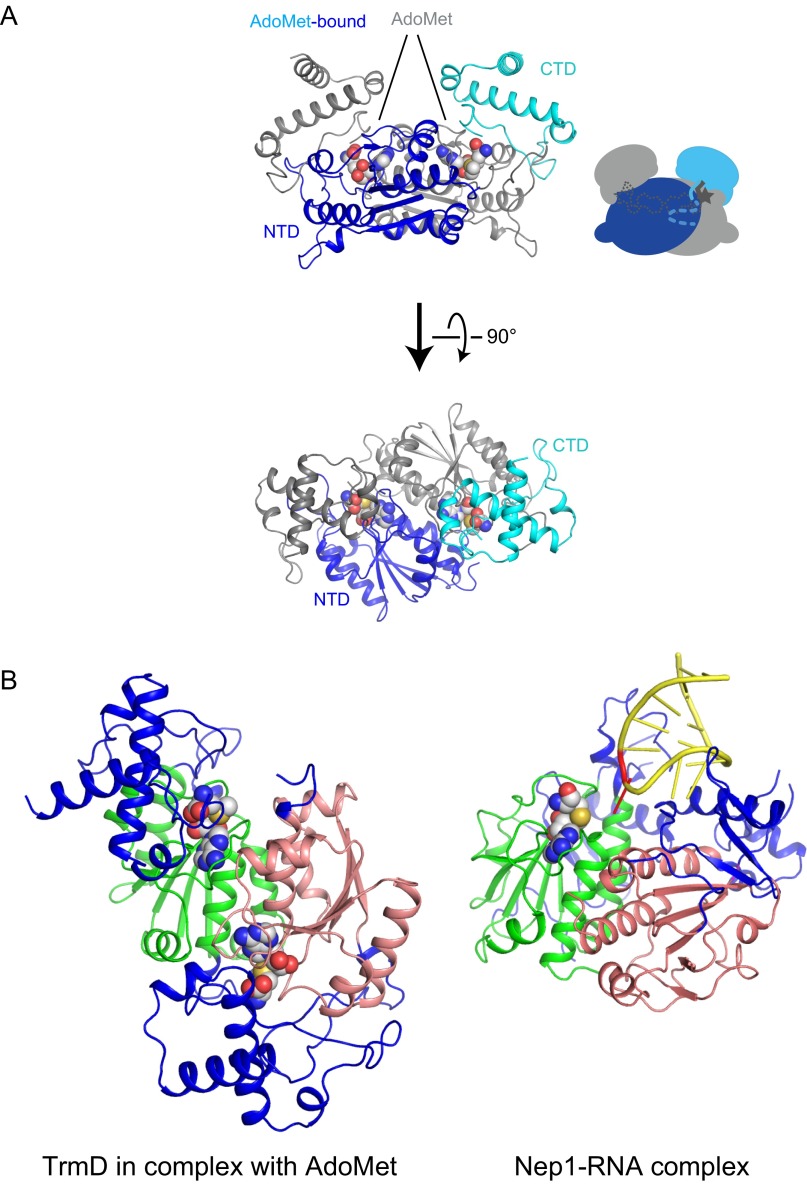

Fig. S1.

Comparison of the TrmD and Nep1 structures. (A) Ribbon representation of the crystal structure of the complex between TrmD and S-adenosyl-l-methionine (AdoMet): the tRNA-free AdoMet-bound form of TrmD. One subunit of the dimeric TrmD is colored blue and light blue for the NTD and CTD, respectively, and the other symmetric subunit is colored gray. The bound AdoMet molecule is represented by a CPK model. (B) Ribbon representations of TrmD in complex with AdoMet and Nep1 in complex with an RNA substrate are shown, and the SPOUT core domains of subunit A of TrmD and Nep1 are presented from the same viewing angle. The Nep1-bound RNA molecule is colored yellow, and the methylation residue is highlighted in red. The characteristic SPOUT domain structures are colored green and salmon for subunits A and B, respectively, and the specific structures of TrmD or Nep1 are colored blue. The TrmD-bound AdoMet and Nep1-bound AdoHcy are depicted by CPK models.

So far, only one SPOUT MTase in complex with a substrate RNA has been crystallized: the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Nep1•RNA complex (Fig. S1B) (13). Nep1 is the SPOUT MTase specific to the N1 position of Ψ1191 in the 18S rRNA (14, 15), but the importance of Nep1 actually resides in its chaperone function, rather than its methylation function. The TrmD and Nep1 dimers share quite similar SPOUT domain structures (Fig. S1B), but they exhibit largely different intersubunit orientations with distinct elements added to the SPOUT domain (colored blue in Fig. S1B). Therefore, it is intriguing to investigate how AdoMet binding may affect substrate RNA binding by TrmD.

Here, we report the crystal structures of TrmD in complex with an AdoMet analog, sinefungin (Fig. 1A), in the presence of wild-type and variant tRNA substrates. These structures revealed that the TrmD-specific structural features are the major determinants of tRNA binding and recognition. Furthermore, we performed structure-guided kinetic analyses of TrmD mutants and tRNA variants. Based on these results, we have elucidated the mechanism by which the SPOUT MTase TrmD captures AdoMet in the deep trefoil knot fold and ensures the subsequent m1G37 methylation of 36GG37-containing tRNAs.

Results and Discussion

Structure Determination and Overall Structures.

We purified the TrmD proteins from two species, Thermotoga maritima and Haemophilus influenzae, to crystallize in the complex with the T. maritima transcript and sinefungin. T. maritima possesses the 36GG37 sequence, which is necessary for recognition by TrmD. We successfully crystallized the ternary complex of H. influenzae TrmD, the T. maritima transcript, and sinefungin. Actually, the structure of H. influenzae TrmD was previously well characterized (3), and became the basis for the further structural characterization. Although the enzyme and the substrate are from different species, the T. maritima transcript is methylated by H. influenzae TrmD 2.2- to 99-fold more efficiently than the H. influenzae tRNA transcripts (Fig. S2) (rows A, E, F, and G in Table 1). Therefore, the interaction between H. influenzae TrmD and the T. maritima transcript is sufficiently functional. We determined the structure of this ternary complex of H. influenzae TrmD, sinefungin, and tRNA, referred to as the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form hereafter, at 3.0 Å resolution (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. S3A). We also determined high-quality structures of the tRNA-free H. influenzae TrmD•AdoMet and TrmD•sinefungin binary complexes, referred to as the AdoMet-bound and sinefungin-bound forms hereafter, at 1.55 Å and 1.6 Å resolutions, respectively (Figs. S1A, S3B, and S4A). The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S1.

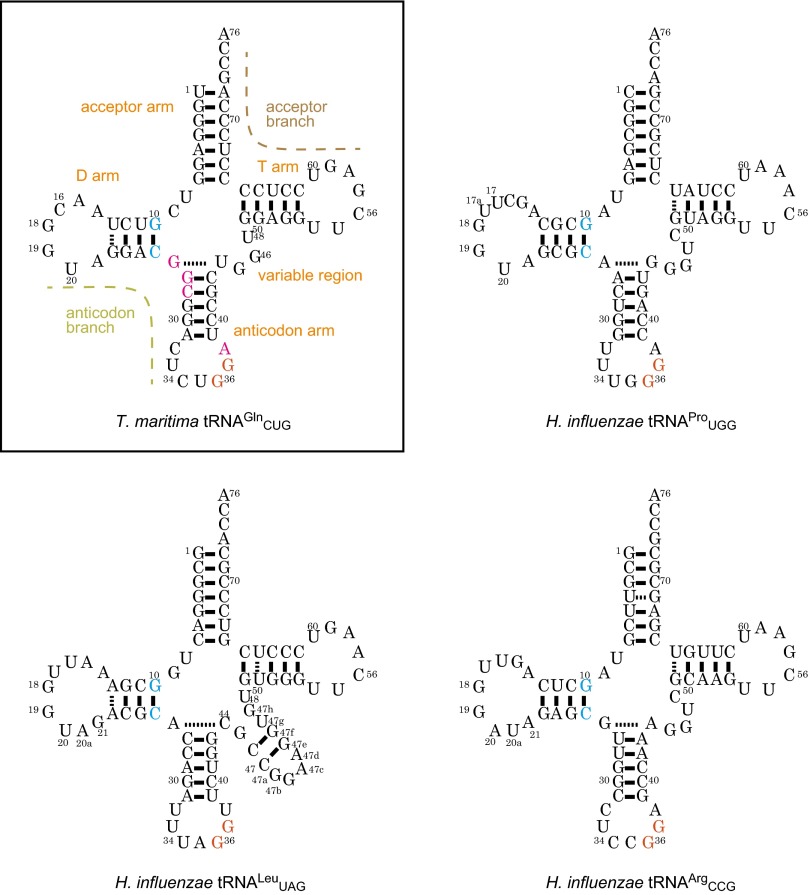

Fig. S2.

Sequences of tRNA transcripts used in this study. The sequences of the transcripts of Thermotoga maritima , Haemophilus influenzae , H. influenzae , and H. influenzae tRNAArgCCG are shown as cloverleaf models. The conserved G10:25C pair and 36GG37 sequence are colored cyan and orange, respectively. In the boxed panel of T. maritima tRNAGlnCUG, the residues with phosphate groups that are recognized by TrmD are colored magenta. In addition, the names of the five arms and the two branches of tRNA are indicated.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetics of H. influenzae TrmD

| Row | Enzyme | tRNA substrate | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (s−1⋅μM−1) | Relative |

| A | Hin TrmD WT | Tma tRNAGln WT | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.15 | 0.29 | 1 |

| B | Hin TrmD WT | Tma tRNAGln G36A | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 0.13 | 1/2.1 |

| C | Hin TrmD WT | Tma tRNAGln G36C | 0.36 ± 0.03 | 184 ± 16 | 0.002 | 1/150 |

| D | Hin TrmD WT | Tma tRNAGln G36U | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 114 ± 1 | 0.0015 | 1/190 |

| E | Hin TrmD WT | Hin tRNAPro | 0.13 ± 0.01 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.13 | 1/2.2 |

| F | Hin TrmD WT | Hin tRNALeu | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 8.0 ± 1.1 | 0.04 | 1/7.1 |

| G | Hin TrmD WT | Hin tRNAArg | 0.078 ± 0.003 | 27 ± 1 | 0.0029 | 1/99 |

| H | Hin TrmD Arg154Ala | Tma tRNAGln WT | 0.0014 ± 0.0002 | 64 ± 1 | 2.2 × 10−5 | 1/13,000 |

| I | Hin TrmD Ser165Ala | Tma tRNAGln WT | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 0.078 | 1/3.7 |

| J | Hin TrmD Asp169Ala | Tma tRNAGln WT | 0.0047 ± 0.0001 | 67 ± 19 | 7.0 × 10−5 | 1/4,100 |

Hin, Haemophilus influenzae; Tma, Thermotoga maritima; WT, wild-type.

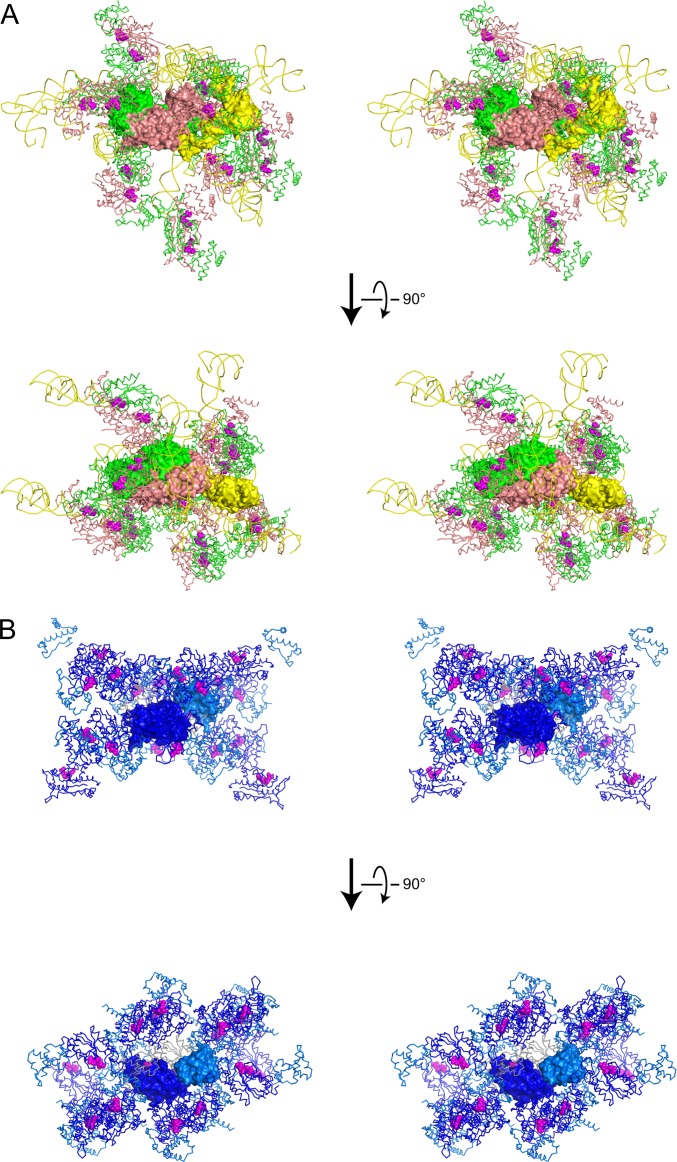

Fig. S3.

Crystal packing of the TrmD•tRNA•sinefungin ternary and TrmD•AdoMet binary complexes. (A) The packing manner in the crystal of the TrmD•tRNA•sinefungin ternary complex is represented in a stereoview from two orthogonal directions. Subunits A and B of TrmD, tRNA, and sinefungin are colored green, salmon, yellow, and magenta, respectively. A central ternary complex, constituting an asymmetric unit, is represented by a surface model, and the interacting symmetric molecules are represented by wire models, except that sinefungin is represented by the CPK model. (B) The packing manner in the crystal of the TrmD•AdoMet binary complex is represented in a similar manner to A. The central asymmetric unit of the TrmD monomer and AdoMet is represented by a surface model, and the other symmetric TrmD and AdoMet are represented by wire and CPK models, respectively. The N-terminal and C-terminal domains of TrmD and AdoMet are colored blue, light blue, and magenta, respectively, except that the TrmD dimerizing with the surface model is colored gray.

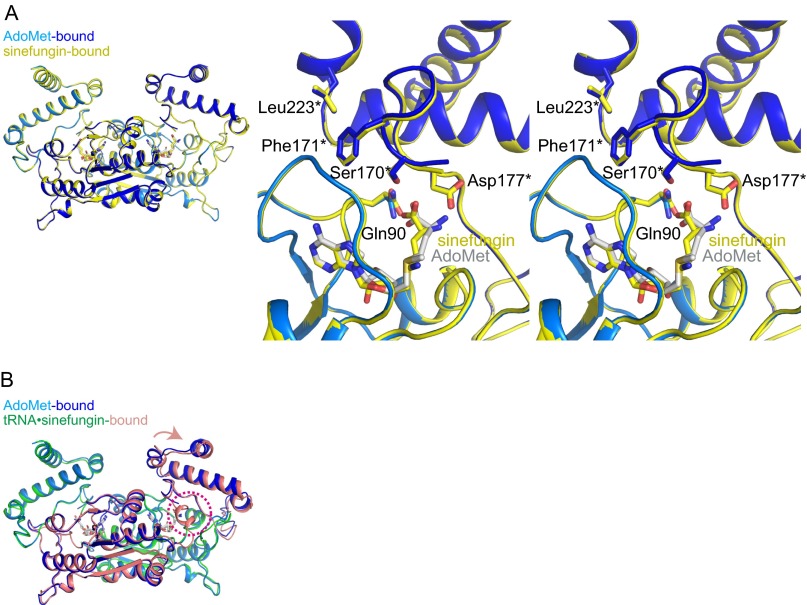

Fig. S4.

Structural comparison between the different forms of TrmD. (A) Structural comparisons between the binary complexes of the AdoMet-bound and sinefungin-bound TrmDs. The structures are overlaid according to the backbone atoms in the NTD. The overall structures and the close-up views of the AdoMet-binding site are presented on the left and right, respectively. Subunits A and B of the AdoMet-bound form are colored blue and light blue, respectively, and the sinefungin-bound form is colored yellow. The models on the right lack the NTD of subunit B, to facilitate visualization (stereoview). (B) Ribbon representations of the AdoMet-bound TrmD and the tRNA•sinefungin-bound TrmD, overlaid according to the backbone atoms in the NTD. The AdoMet-bound binary complex of TrmD is colored as in A, and the tRNA•sinefungin-bound ternary complex of TrmD is colored as in Fig. 2. The structural change of the CTD is indicated by the salmon colored arrow, and the interdomain helix induced by tRNA binding is indicated by the dotted red circle.

Table S1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Data collection and refinement | TrmD-AdoMet | TrmD-sinefungin | TrmD-WT tRNA -sinefungin | TrmD-36U tRNA -sinefungin | TrmD-36C tRNA -sinefungin |

| Data collection | |||||

| Beam line | BL-NW12A in PF | BL5A in PF | BL41XU in SP8 | BL-NE3A in PF | BL32XU in SP8 |

| Space group | R32:H | R32:H | P41212 | P41212 | P41212 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 93.9, 93.9, 178.0 | 93.8, 93.8, 177.9 | 86.8, 86.8, 227.0 | 87.4, 87.4, 229.0 | 87.5, 87.5, 228.7 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 120 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 | 90, 90, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00–1.55 (1.58–1.55) | 50.00–1.60 (1.63–1.60) | 50.00–3.00 (3.11–3.00) | 50.00–2.90 (3.00–2.90) | 50.00–3.00 (3.11–3.00) |

| Rsym | 0.064 (0.969) | 0.061 (0.553) | 0.121 (0.875) | 0.151 (0.852) | 0.153 (0.694) |

| I/σI | 43.7 (3.0) | 30.2 (3.6) | 20.7 (2.1) | 20.0 (2.5) | 20.2 (2.3) |

| Redundancy | 11.2 (11.2) | 6.1 (6.0) | 10.3 (9.3) | 9.9 (8.8) | 7.3 (7.4) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.2 (96.9) | 99.8 (100.0) | 99.6 (99.9) | 99.6 (99.8) | 99.8 (99.9) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 36.8–1.55 | 23.3–1.60 | 34.5–3.0 | 31.6–2.9 | 43.7–3.0 |

| No. of reflections | 40917 | 39805 | 17858 | 20515 | 18457 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.174/0.201 | 0.186/0.219 | 0.219/0.283 | 0.199/0.278 | 0.219/0.283 |

| Number of atoms | |||||

| Protein | 1,891 | 1,896 | 3,848 | 3,846 | 3,846 |

| RNA | — | — | 1,519 | 1,516 | 1,516 |

| AdoMet/Sinefungin | 27 | 27 | 54 | 54 | 54 |

| Water | 280 | 242 | — | — | — |

| B-factors (Å2) | |||||

| Protein | 20.1 | 22.3 | 89.7 | 64.6 | 79.2 |

| RNA | — | — | 104.7 | 88.4 | 104.6 |

| AdoMet/Sinefungin | 17.9 | 18.5 | 73.6 | 54.5 | 66.1 |

| Water | 34.4 | 32.9 | — | — | — |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.020 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.018 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.95 | 1.54 | 1.39 | 1.59 | 1.33 |

| Ramachandran plot | |||||

| Favored/allowed (%) | 99.1/0.9 | 99.2/0.8 | 97.7/2.1* | 97.9/2.1 | 97.9/2.1 |

| PDB ID code | 4YVG | 4YVH | 4YVI | 4YVJ | 4YVK |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

One residue (Leu229 in subunit B) is plotted slightly outside the allowed region in Ramachandran plot.

The crystal structures of the AdoMet-bound and sinefungin-bound forms of TrmD are almost the same. The asymmetric unit contains one TrmD subunit bound to one AdoMet or sinefungin molecule, and a homodimer is formed between the symmetry-related subunits (Figs. S1A, S3B, and S4A). H. influenzae TrmD consists of the NTD (residues 1–160) and the CTD (residues 169–246) (Fig. S1A), and the interdomain linker of residues 161–168 is disordered in the tRNA-free structures. These characteristics are consistent with those previously reported for the AdoMet- and AdoHcy-bound TrmD structures (PDB ID codes 1UAK, 1UAL, 1UAM, and 1P9P) (3, 5). Minor conformational differences were identified in the sugars and between the methionine and methionine-mimicking moieties of AdoMet and sinefungin (Fig. S4A). The sugar moieties of AdoMet and sinefungin adopt the C2′- and C3′-endo conformations, respectively, probably because of the chemical differences between the methyl donor and the analog.

In the crystal structure of the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form, the asymmetric unit contains the TrmD homodimer in complex with one tRNA molecule (Fig. 1B and Fig. S3A). However, each of the two catalytic pockets holds a sinefungin molecule, similar to the sinefungin-bound form, in which sinefungin is partially buried in the cavity constructed by the deep trefoil knot structure (Fig. 1C). The substrate tRNA interacts with the catalytic pocket involving the knot of subunit A, the NTDs of subunits A and B, and the neighboring CTD of subunit B (Fig. 1B). The identified stoichiometry between the TrmD monomer, sinefungin, and tRNA of 2:2:1 is consistent with the previous biochemical results (16). Upon tRNA binding, the CTD of subunit B changes its conformation to snugly contact the tRNA (arrow in Fig. S4B), and therefore the TrmD dimer is no longer conformationally symmetric. Consistent with biochemical studies (17), TrmD recognizes only the tRNA anticodon branch, composed of the D and anticodon arms, and the variable region (colored yellow in Fig. 1B), and lacks any contacts with the acceptor branch, formed by the acceptor and T arms (colored brown in Fig. 1B). The interdomain linker of subunit B forms a helix upon tRNA binding, and participates in the interaction with the substrate tRNA (Fig. 1B and the red dotted circle in Fig. S4B).

The Interaction with G37.

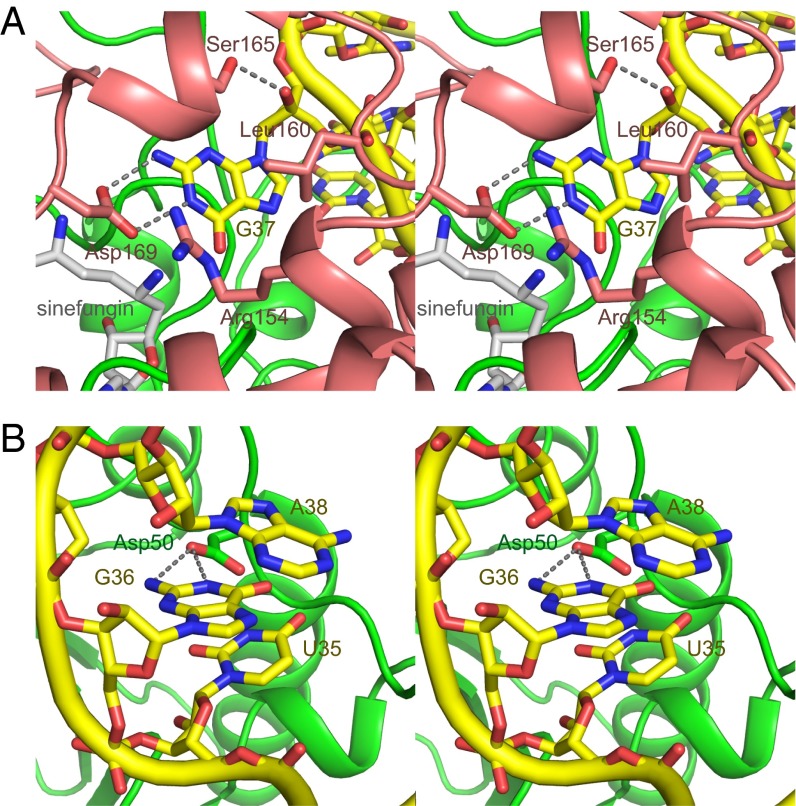

In the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form, the base moiety of G37 is flipped out from the anticodon loop, and protrudes into the catalytic pocket (Figs. 1B and 2A). The 1-NH and 2-NH2 groups of G37 hydrogen bond with the side-chain carboxyl group of Asp169 of subunit B. Hereafter, a residue name with an asterisk, such as “Asp169*,” indicates that of subunit B, and a residue name without an asterisk refers to that of subunit A. In all TrmD enzymes, this position is occupied by a negatively charged residue, such as aspartate or glutamate (Fig. S5). The side-chain of Leu160* stacks onto the guanine base, and the γ-OH group of Ser165* hydrogen bonds with the 2′-OH group of G37. In addition, the side-chain of Arg154* is close to the guanine base. The ε amino group of sinefungin, corresponding to the donor methyl group of AdoMet, is located next to the 1-NH group of G37, which is a suitable position for methyl-transfer after deprotonation of the 1-NH proton. The identified G37-interaction manner (Fig. 2A) is consistent with the results of a study of tRNAs containing guanosine analogs of G37 (18).

Fig. 2.

TrmD interactions with G37 and G36 in the target tRNA. (A) Close-up views of the G37-binding pocket (stereoview). The molecules are colored as in Fig. 1B, except that sinefungin is colored gray. The interacting residues of TrmD and sinefungin are indicated by stick models. The hydrogen bonds between TrmD and tRNA are indicated by gray dotted lines. (B) Close-up views of the G36-binding pocket (stereoview). The molecules are depicted as in A.

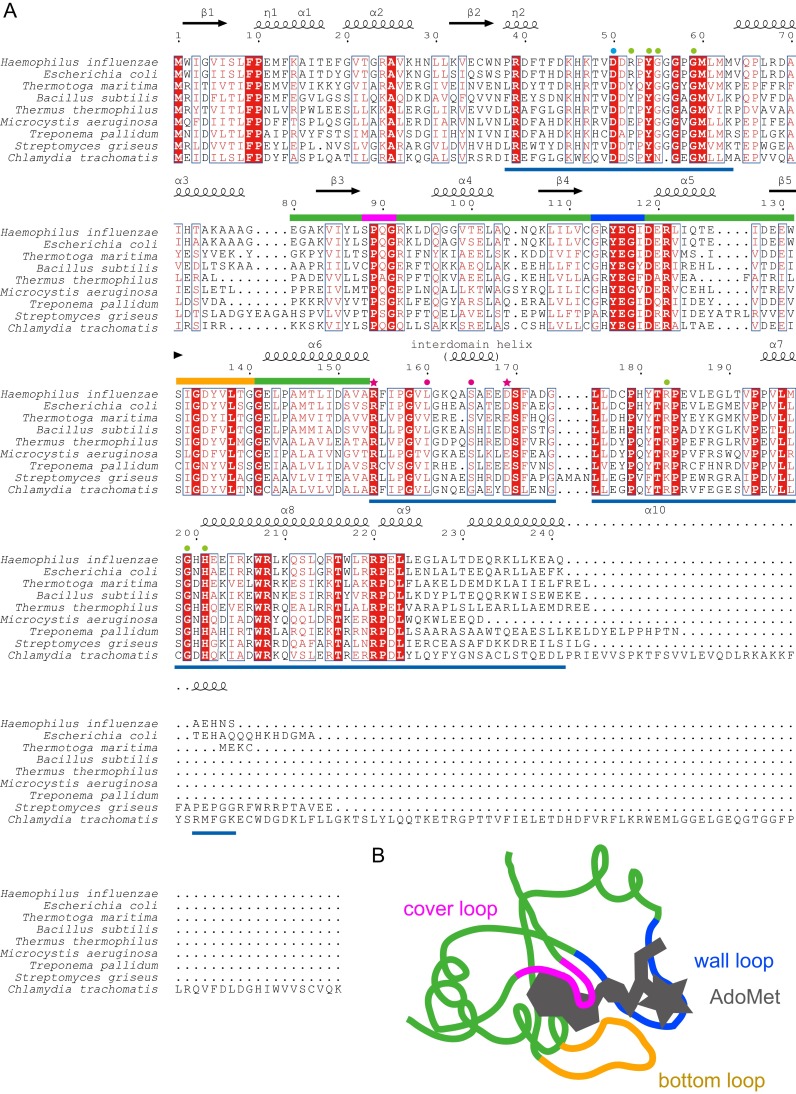

Fig. S5.

Sequence alignment of TrmDs. (A) Amino acid sequences of TrmD enzymes from nine bacteria (H. influenzae, Escherichia coli, T. maritima, Bacillus subtilis, Thermus thermophilus, Microcystis aeruginosa, Treponema pallidum, Streptomyces griseus, and Chlamydia trachomatis) were aligned by the program ClustalW (41), and visualized by the program ESPript (42). The fully conserved residues are highlighted in red boxes, and the moderately conserved residues are indicated by red characters. The secondary structural elements are indicated above the sequences. The G36-interacting residues, the G37-interacting residues, and the anticodon branch-interacting residues are indicated by cyan, magenta, and green circles, respectively. The G37-interacting catalytic residues of Arg154 and Asp169 are indicated by magenta stars. The deep trefoil-knot region is indicated by green bars, except that the cover, wall and bottom loops are indicated by magenta, blue, and orange bars, respectively. The TrmD-specific structures are indicated by blue lines under the sequences. (B) The schematic deep trefoil-knot structure is indicated with the bound AdoMet, which is also shown in Fig. S9 D and E. The cover, wall and bottom loops are colored as in A.

Next, we performed kinetic analyses with TrmD mutants, to evaluate the importance of the aforementioned residues (Table 1). The Arg154Ala and Asp169Ala mutations essentially abolished the activities. These mutations affected both the kcat and Km and decreased the kcat/Km values of Arg154Ala and Asp169Ala by 13,000- and 4,100-fold, respectively (rows H and J in Table 1). Therefore, these two residues play important roles in the catalysis of methyl transfer, consistent with the previous biochemical studies of Escherichia coli TrmD (5). In contrast, the Ser165Ala mutation had a modest influence on the TrmD activity (compare row I with row A in Table 1), consistent with the data showing that the 2′-OH group of G37 is not critical for TrmD (18).

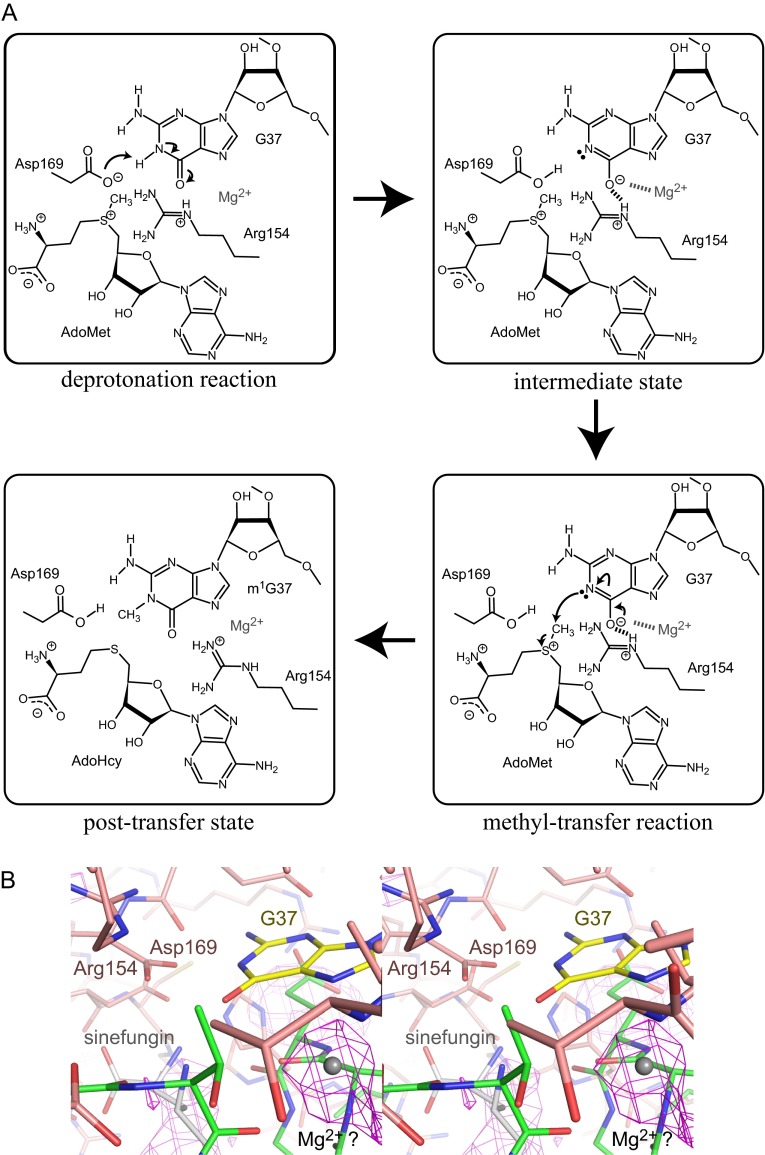

Based on our crystal structure and kinetic analyses, we propose a mechanism for methyl transfer by TrmD (Fig. S6A). First, the negatively charged side-chain carboxyl group of Asp169* functions as a catalytic general base, and abstracts the proton from N1 of G37. In the resultant intermediate state, the developing negative charge on O6 of G37 is stabilized by the positively charged guanidine group of the strictly conserved Arg154*. In a recent study, a Mg2+ ion was found to stabilize the developing negative charge on O6 of G37 after proton abstraction, thus contributing to the catalytic mechanism of methyl transfer (19). In the mFo-DFc map of the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form, a weak electron density was identified near N7 of G37, which might be a partially bound Mg2+ ion (Fig. S6B). The deprotonated N1 atom of G37 then nucleophilically attacks the methyl group of AdoMet, generating the m1G37-modified tRNA with AdoHcy as the leaving group.

Fig. S6.

Proposed mechanism of the catalytic reaction. (A) The proposed mechanism of the catalytic reaction is indicated in four panels: the deprotonation reaction, the intermediate state, the methyl-transfer reaction, and the posttransfer state. In the intermediate state, the electrostatic interaction between G37 and Arg154 is indicated by bold dotted lines. The Mg2+ ion, which stabilizes the developing negative charge on O6 of G37, and its interaction with O6 of G37 are indicated by a gray character and a dotted line, respectively. (B) Close-up views of the presumed Mg2+ ion-binding site in the TrmD•tRNA•sinefungin ternary complex (stereoview). The possible position of the Mg2+ ion is indicated by the gray ball, and the other molecules are indicated by line models, colored as in Fig. 2A. The mFo-DFc map, contoured at 3σ, is illustrated on the model by a magenta mesh.

The Interaction with G36.

As shown in Fig. 2B, the 1-NH and 2-NH2 groups of G36 interact with the side-chain carboxyl group of Asp50, which is strictly conserved in TrmD (Fig. S5A). This interaction stabilizes the guanine base in the syn conformation, which is rarely observed in tRNA molecules (Fig. 2B). The guanine base at position 36 is sandwiched between the bases of A38 and U35. The distance between the N9 atoms of G36 and A38 is only 4.1 Å, which is shorter than the corresponding distance between the adjacent stacking residues in a regular RNA double helix (∼4.8 Å), and there is no space for G37 to be inserted between the bases of G36 and A38. Thus, the identified G36-interacting pocket is formed only after the guanine base at position 37 is flipped from the loop and held by TrmD, indicating that the G36 interaction occurs after the G37 interaction.

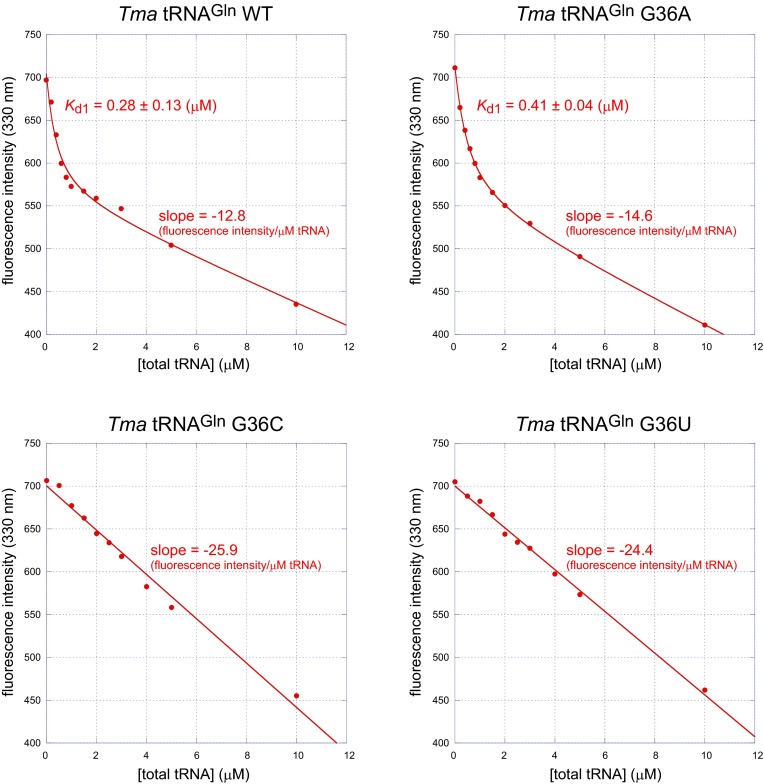

To examine the influence of the G36 interaction on the methyl transfer reaction, we analyzed TrmD kinetics with the tRNA variants G36A, G36U, and G36C, as well as the wild-type. The G36A variant was methylated by TrmD almost as efficiently as the wild-type, although the Km value was slightly higher than that of the wild-type (rows A and B in Table 1). The 6-NH2 group of G36A is probably recognized by one of the carboxyl oxygen atoms of Asp50. It is noteworthy that the 36AG37 tRNA sequence does not naturally occur in bacteria. In contrast, the methyl transfer efficiencies with the G36C and G36U variants fell to 1/150 and 1/190, respectively, of the wild-type level (rows A, C, and D in Table 1). The Km values of the G36C and G36U variants were more than 100-times higher than that of the wild-type, whereas the kcat values changed only slightly. Presumably, the side-chain of Asp50 is too short to capture a pyrimidine base. We measured the affinities between sinefungin-bound TrmD and tRNA variants, as well as the wild-type, by monitoring the quenching of the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of TrmD (Fig. S7). Compared with the dissociation constants for the wild-type tRNA (0.28 μM) and the G36A tRNA variant (0.41 μM), TrmD exhibited largely reduced affinities for the G36C and G36U tRNA variants (Kds were not determined), consistent with the Km values described above.

Fig. S7.

Binding experiments between sinefungin-bound TrmD and tRNA variants. The tRNA-binding was monitored by the quenching of the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of TrmD. For the wild-type and G36A tRNAs, the determined dissociation constants for the first strong tRNA binding (Kd1) are indicated next to the fitting lines. The calculated slopes for the weak binding are also indicated.

Comparison of the Structures in the Absence and Presence of the G36 Interaction.

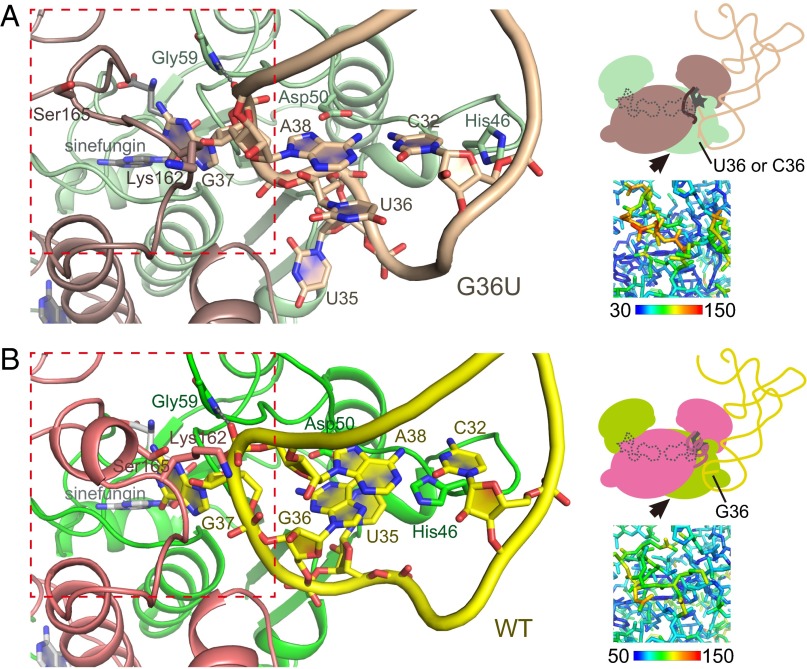

To reveal how the local G36 interaction influences the overall substrate interaction and the enzymatic reaction, we successfully determined the crystal structures of TrmD•sinefungin in complex with the G36U or G36C tRNA variant (Table S1). In each complex, the stoichiometry of the tRNA to the enzyme dimer remained the same as that in the wild-type complex. Because the tertiary structures with these two variants are almost the same, hereafter the structure of the G36U tRNA variant (Fig. 3A) is used for comparison with the wild-type structure (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

The structural changes induced by the G36 interaction. (A) Ribbon representation of the ternary complex of TrmD, sinefungin, and the G36U variant tRNA (Left), together with the schematic representation (Right Upper), and the stick model colored with B-factors (Right Lower). The key residues are depicted by stick models and labeled. The peptide bond between Gly59 and Pro58 is depicted by a stick model, and the hydrogen bond from the NH group of Gly59 is indicated by the gray dotted line. The viewpoint of the left panel is indicated by the black arrow in the schematic representation. The red dotted square corresponds to the region represented in the B-factor-colored model in the right lower panel. The colors of the molecules are fainter than those of the wild-type, as in Fig. 2. (B) Representations of the ternary complex of TrmD, sinefungin, and the wild-type tRNA, in the same manner as in A.

As expected from our kinetic experiments, we observed that the uracil base at position 36 does not interact with Asp50 in the variant structure, and is directed to the outside of the anticodon loop with the regular anticonformation (Fig. 3A). Because the G36 interaction with Asp50 is lost in the U36-tRNA structure, the extensive stacking between A38:C32 and G36 is also absent (Fig. 3A). In addition, the hydrogen-bonding partner of the main-chain NH group of the strictly conserved Gly59 is different: it is the O1P atom of A38 in the variant structure but the O2P atom in the wild-type structure, as indicated by the dotted lines in Fig. 3. Thus, we have designated these anticodon-arm structures as the “loose” and “tight” forms in the absence and presence, respectively, of the G36 interaction.

Although many differences have been identified between the wild-type and variant structures, the coordinates of the G37 base are quite similar between them (Fig. 3). This observation strongly suggests that the interaction of TrmD with G37 is independent of the interaction with G36, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the G36 interaction is established only after the G37 base is flipped out from the anticodon loop.

Regarding TrmD in the variant structure, the orientation of the His46 side-chain is quite different. The imidazole ring flips outside in the variant structure, while it stacks on the C32 base in the wild-type structure (Fig. 3), where the interaction between His46 and C32 would contribute to the conformational change of the anticodon arm. Most importantly, the interdomain helix between the NTD and the CTD, which becomes helically ordered upon wild-type tRNA binding, remains disordered in the variant structure (Fig. 3A), presumably because of steric hindrance between the interdomain helix and the anticodon arm of the variant tRNA. If the helix was formed in the variant structure, then the side-chain of Lys162* in TrmD would collide with the sugar moiety of A38 in the tRNA (Fig. 3). The interdomain region of the variant seems to be quite mobile, as indicated by its higher B-factors (Fig. 3A), and waters may easily enter the G37-interacting pocket, which would weaken the hydrogen bonds between Asp169* and G37. However, the stable formation of the interdomain helix prevents waters from entering the G37-interacting pocket (Fig. 3B). The disordered state of the interdomain linker was also observed in the tRNA-free binary complexes. Based on the ordering of the interdomain linker upon tRNA binding, we suggest that the insertion of G37 into the active site enables the interaction between Asp50 and G36, which induces additional conformational changes that further strengthen the interactions with G37 for the methyl transfer reaction.

Selection of tRNA Anticodon Branch and Detection of Position 37.

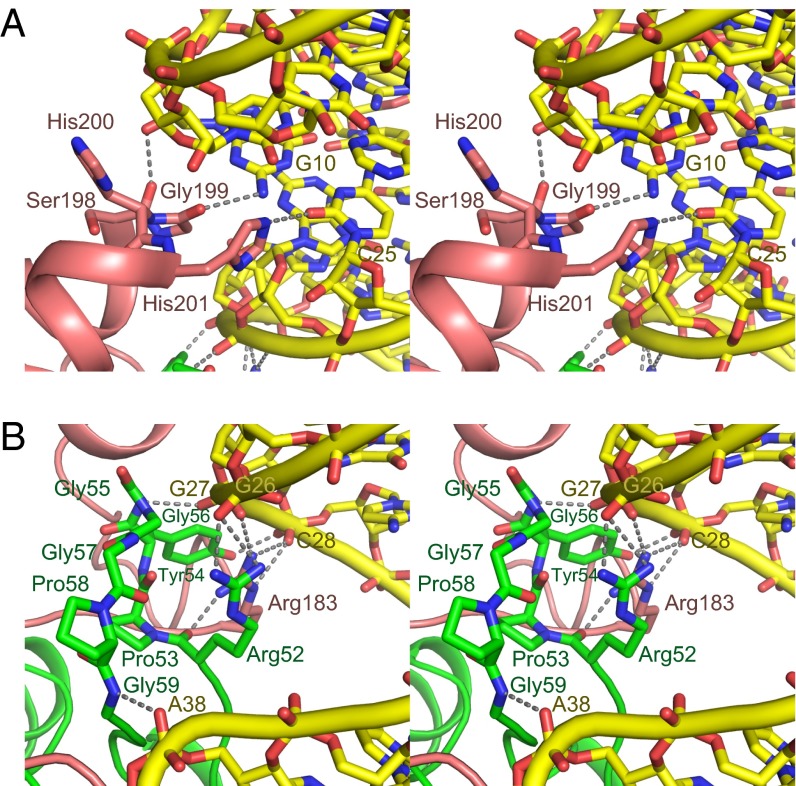

The manner in which TrmD interacts with the D and anticodon stems determines how TrmD searches for position 37 in substrate tRNAs. As shown in Fig. 4A, the CTD of subunit B binds to the D-stem end. The conserved Ser-Gly-His/Asp-His residues, located between helices α7 and α8 in the CTD, recognize the minor groove next to the G10:C25 base pair, which is conserved in all of the substrate tRNAs in H. influenzae. The identified recognition manner indicates that TrmD is able to similarly recognize the G10:U25 pair in the TrmD•substrate tRNAs from other species. However, the strong binding between TrmD and tRNA is likely to be established by the recognition of the phosphate groups on the 5′ strand of the anticodon arm, by the CTD of subunit B and the NTD of subunit A (Fig. 4B). The main-chain NH group of Gly55 and the side-chains of Arg52, Arg183*, and Tyr54, which are highly conserved in TrmDs (Fig. S5A), form networks with the phosphate groups of G26, G27, and C28, by electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions. Finally, the main-chain NH group of Gly59 interacts with the phosphate group of A38, located 3′ adjacent to the target position 37. This cascade of interactions allows TrmD to find and recognize the base moiety at position 37 in the tRNA.

Fig. 4.

The interaction between the anticodon branch and TrmD to find position 37. (A) The loop between helices α7 and α8 recognizes the minor groove next to the G10:C25 pair (stereoview). The key residues in TrmD are depicted by stick models. The identified electrostatic and hydrogen bonds are indicated by the dotted gray lines. (B) The recognition of the phosphate groups of G26, G27, C28, and A38 by TrmD is indicated in the same manner as in A.

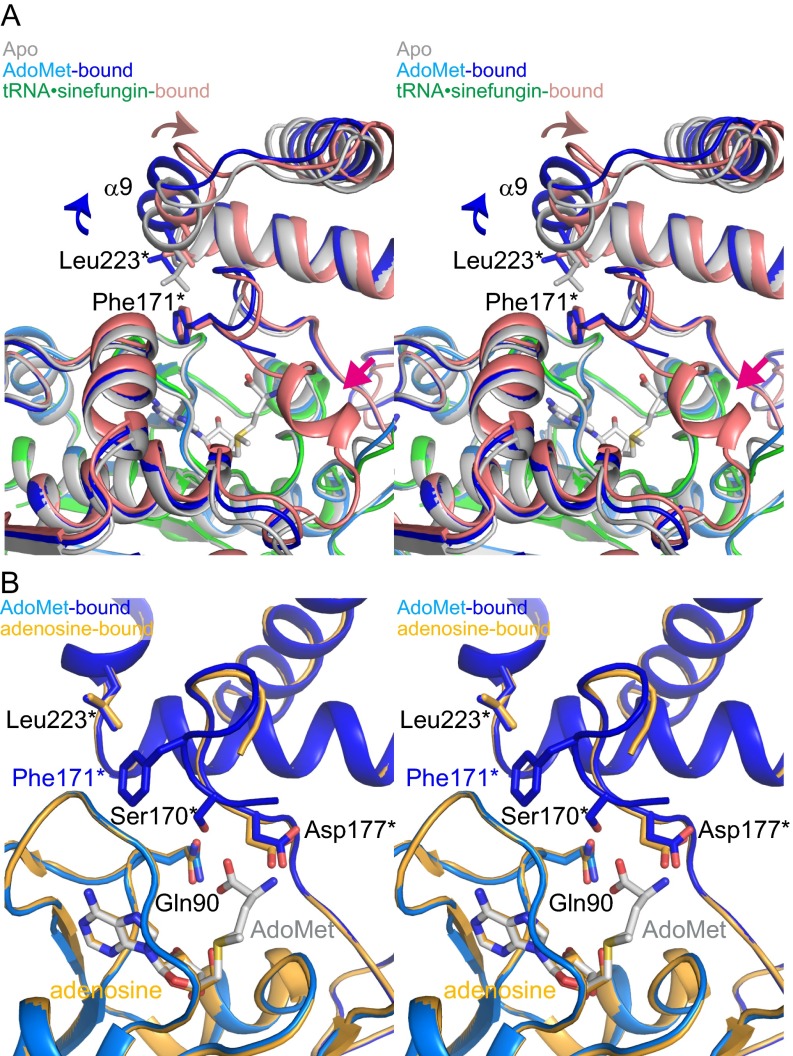

Structural Changes of TrmD upon AdoMet Accommodation.

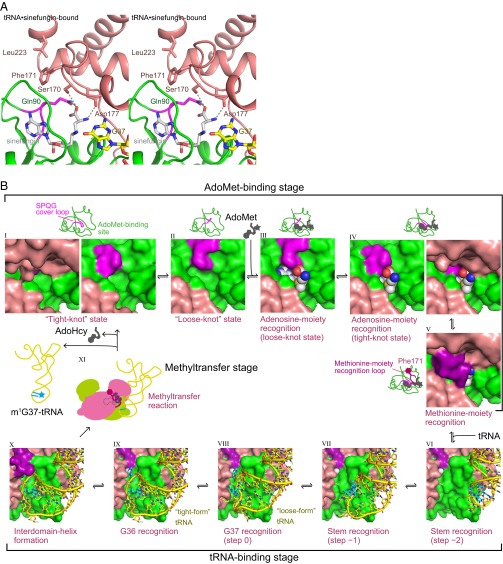

A comparative analysis of the tRNA•sinefungin-bound, AdoMet-bound, and previously determined apo (PDB ID code 1UAJ) (3) TrmD structures revealed several key differences around the AdoMet-binding site. The most notable is the orientation of Phe171* in the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form (Fig. 5A and Fig. S8A), which is inserted between the CTD of subunit B and the NTD of subunit A. Phe171* is next to the residues that form a pocket for the carboxyl and amino groups of the methionine-mimicking moiety of sinefungin. Other residues of the pocket include Gln90, Ser170*, and Asp177* (Fig. 5A). This orientation of Phe171* was also observed in the AdoMet-bound form, even though the interdomain linker was disordered. Intriguingly, the specific orientation of Phe171* was not observed in our previously determined TrmD structure in complex with adenosine, lacking the methionine moiety (PDB ID code 3AXZ) (Fig. S8B) (20). It appears that the interaction between the methionine moiety of AdoMet and the binding pocket of TrmD is necessary for the stable insertion of Phe171*.

Fig. 5.

A model of the enzymatic cycle of TrmD. (A) The AdoMet-binding site of the tRNA•sinefungin-bound TrmD (stereoview). The residues recognizing the methionine-mimic moiety of sinefungin are depicted by stick models, and the identified hydrogen bonds are indicated by the dotted gray lines. The model lacks the NTD of subunit B to facilitate visualization, and is colored as in Fig. 2, except that the 88SPQG91 cover loop is colored magenta. (B) Based on the crystal structures, the kinetic experiments and the structural analyses, the recognition order of AdoMet and the elements in the 36GG37-containing tRNA, and the subsequent methyl transfer reaction by TrmD are presented. The states in the AdoMet-binding stage (states I to V) are illustrated as close-up views of the AdoMet-binding site with schematic trefoil-knot structures, those in the tRNA-binding stage (states VI to X) are illustrated around the tRNA-binding site, and the methyltransfer stage (state XI) is illustrated schematically. The TrmD, AdoMet, and tRNA in the graphical panels are depicted by surface models, CPK models, and stick models with ribbons, respectively. The figures are colored as in Fig. 2, except that the nucleotides at positions 36 and 37 are colored cyan, the 88SPQG91 cover loop is colored magenta, and the ordered loop in the CTD and the interdomain helix are colored purple. The right panel of state I, the panels of states II and III, and the left panel of state IV lack the CTD of subunit B, to facilitate visualization.

Fig. S8.

Structural differences among the various forms of TrmD around the AdoMet-binding site. (A) Ribbon representations of the apo, AdoMet-bound, and tRNA•sinefungin-bound TrmDs are overlaid, according to the backbone atoms in the NTD of subunit A (stereoview). The key residues are depicted by stick models. The structural change from the apo to AdoMet-bound form is indicated by the blue arrows, and that from the AdoMet-bound to tRNA•sinefungin-bound form is shown by the salmon arrows. The interdomain helix in the tRNA•sinefungin-bound form is indicated by the magenta arrow. (B) Structural comparison between the AdoMet-bound and adenosine-bound TrmDs (stereoview). The structures are overlaid according to the backbone atoms in the NTD. The AdoMet-bound form is colored as in Fig. S4A, and the adenosine-bound form is colored yellow. The models lack the NTD of subunit B, to facilitate visualization. The specific orientation of Phe171* is observed only in the AdoMet-bound and tRNA•sinefungin-bound TrmDs.

In the apo form, in addition to the disorder of the interdomain linker, the following five residues from Gly161* to Asp173* in the CTD are also disordered, probably because of the lack of interaction with any ligand, such as AdoMet (Fig. S8A) (3). In the apo form, Phe171* is not inserted as in the AdoMet- or tRNA•sinefungin-bound form; instead, the side-chain of Leu223* of the CTD is inserted into the corresponding groove, whereas the CTD is displaced, especially around the α9 helix (Fig. S8A).

How does TrmD accommodate the AdoMet molecule? In the AdoMet-bound form, the adenosine moiety of AdoMet, especially the adenine-base part, is buried in the deep trefoil knot structure of TrmD (state IV in Fig. 5B). However, the structure of the deep trefoil knot fold does not seem to be capable of accommodating AdoMet within its binding site in TrmD without any steric hindrance (state I in Fig. 5B). These considerations raised the possibility that TrmD undergoes a conformational change during AdoMet accommodation.

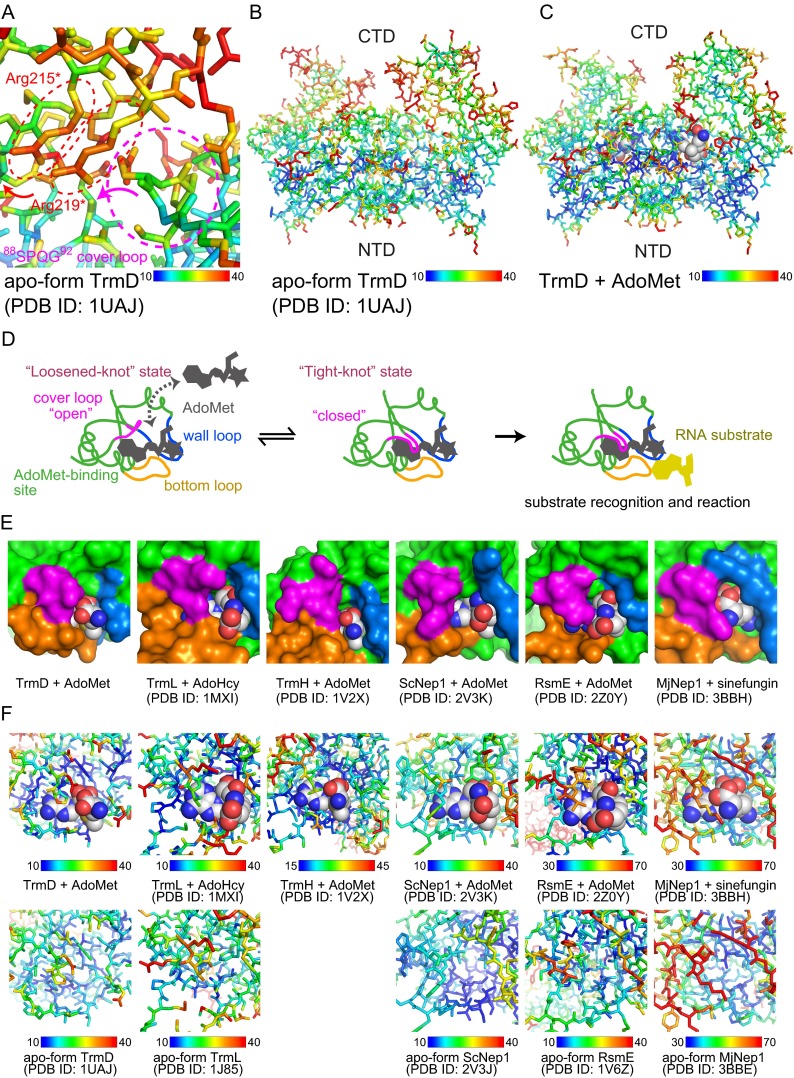

We therefore investigated the TrmD movement that would allow the accommodation of AdoMet. First, we looked at the B-factors around the AdoMet-binding sites of the determined structures, and found that the 88SPQG91 loop (referred to as the “cover loop,” hereafter) in the middle of the deep trefoil knot structure (colored magenta in Fig. 5B), and the side-chains of Arg215* and Arg219* in the CTD, have relatively high B-factors in the apo form (Fig. S9A). Manual modeling of the structure revealed that the small movements of the side-chains of Arg215* and Arg219* create space for the 88SPQG91 cover loop to open the AdoMet-binding site. The cover-loop motion may involve the movement of the entire CTD, because of its relatively high B-factors in both the apo and AdoMet-bound forms (Fig. S9 B and C). Because the knot structure is not involved in the crystal packing contacts (Fig. S3), the B-factors around the knot structure are affected mainly by the mobility of the structure. As a result, the open conformation of the 88SPQG91 cover loop allows AdoMet to enter its binding site (from state II to state III in Fig. 5B). In other words, the deep trefoil knot of TrmD can be loosened, thus opening the pocket to accommodate AdoMet. After accommodating the adenine base moiety, the knot can be retightened, which results in the AdoMet-bound form (state IV in Fig. 5B) (3).

Fig. S9.

Structural analysis of AdoMet accommodation. (A) Expanded view of the B-factor mapping around the 88SPQG92 cover loop of the apo-form TrmD. The cover loop and the two key arginine residues are encircled by the dashed light magenta and red ellipses, respectively. The B-factors in each model are mapped onto the stick model, and the B-factor color spectrum is indicated below. (B and C) The B-factor maps of the (B) apo and (C) AdoMet-bound TrmDs. The stick models are represented from the same angle as in the top panel of Fig. S1A. These panels show that the B-factors of the CTD are generally higher than those of the NTD. (D) Schematic representation of the function of the deep trefoil knot structure of the SPOUT MTases in the accommodation of AdoMet and the following target interaction. The cover, wall, and bottom loops from the deep trefoil knot are colored magenta, blue, and orange, respectively. (E) Structural comparison of the AdoMet-binding sites in the SPOUT MTases. Six SPOUT domains from TrmD (3), TrmL (4), TrmH (43), ScNep1 (44), RsmE, and MjNep1 (45) are represented by green surface models. All figures represent the monomer to facilitate visualization. The cover, wall, and bottom loops from the deep trefoil knot are colored as in D, and the bound AdoMet, AdoHcy, or sinefungin is indicated by a CPK model. The reference PDB ID codes are indicated under each panel. (F) The B-factor mapping of the AdoMet-binding sites from the six SPOUT MTases indicated in E. The AdoMet/AdoHcy/sinefungin-bound and apo SPOUT MTases are shown at the top and the bottom, respectively, together with the color spectrum of the B-factors, the enzyme name, and the PDB ID code.

We then examined the AdoMet-binding sites of other SPOUT MTases. The AdoMet-binding site of the SPOUT domain mainly consists of three loops from the deep trefoil knot: the cover, wall, and bottom loops (colored magenta, light blue, and orange, respectively, in Figs. S5B and S9D). The bottom loop, corresponding to residues Ser132 to Gly140 in TrmD, constructs the bottom of the AdoMet-binding site, and touches the other dimerizing SPOUT domain. The wall loop corresponds to residues Gly113 to Ile118 in TrmD, and forms a wall next to the methionine moiety of AdoMet. The cover loop corresponds to the residues 88SPQG91 in TrmD, and buries the adenosine moiety, as described above. This architecture of the three loops is common among six of the structurally characterized SPOUT domains (Fig. S9E). In all cases, the B-factors of the cover loop are higher than those of the wall and bottom loops in both the AdoMet(-analog)/AdoHcy-bound and apo forms (Fig. S9F). Therefore, the mechanism for AdoMet-accommodation by TrmD, starting with the opening of the cover loop, seems to be common among the SPOUT MTase family members (Fig. S9D).

The Overall Enzymatic Cycle of TrmD.

Based on the results described above, we propose a model for the TrmD enzymatic cycle, which is divided into three major stages: the AdoMet-binding, tRNA-binding, and methyl transfer stages (Fig. 5B).

The apo-form TrmD is likely to shuttle between the “tight-knot” (state I) and “loose-knot” (state II) states, by establishing an equilibrium between the closed and open conformations of the cover loop, and only TrmD in the “loose-knot” state is able to accommodate AdoMet without any steric hindrance (state III). In the loose-knot state, the adenosine moiety of AdoMet is captured in the hollow constructed by the deep trefoil knot structure in TrmD (state IV), whereas the methionine moiety is recognized by Gln90, Ser170*, and Asp177* (state V). The AdoMet recognition induces the stable insertion of the Phe171* side-chain, allowing the CTD to assume the tRNA-binding form preferentially and transitioning the structure into the tight-knot state. The importance of the insertion of Phe171* is consistent with the fact that the Ala substitution in E. coli TrmD abolishes the enzyme activity (5).

The AdoMet-bound TrmD then searches for a substrate tRNA. We hypothesize that TrmD binds first to the anticodon stem of the substrate tRNA with the canonical shape of the anticodon loop, and then the loop conformation changes to insert G37 into its binding pocket within TrmD (state VIII). However, if the tRNA anticodon stem binds in the manner observed in the crystal structures, then the canonical anticodon loop conformation sterically clashes with TrmD. In fact, TrmD interacts mainly with the phosphate groups at positions 26, 27, and 28 of the anticodon stem, from the minor groove side, in the crystal structures (“step 0”). We therefore hypothesized that TrmD can interact with the phosphate groups at positions 27, 28, and 29 (“step –1”) or positions 28, 29, and 30 (“step –2”). The steric hindrance with the canonical conformation of the anticodon loop is much less in step –1 than in step 0, and is negligible in step –2. Therefore, step –2 was postulated to be the first step of the anticodon binding (state VI). Then, TrmD and the anticodon stem are likely to mutually slide to step –1, together with the conformational change of the inherently flexible anticodon loop (state VII). Finally, one more slide to step 0 allows the main-chain NH group of Gly59 to capture the phosphate group at position 38, which becomes a landmark for the insertion of the base moiety at position 37 within the catalytic pocket (state VIII). Once the base at position 37 is judged as a guanine and interacting tightly, the pocket for position 36 searches for G36 (state IX). Immediately after G37 recognition, the anticodon arm is probably in the “loose form,” as in the crystal structures with U or C at position 36. The guanine base in the loose form at position 36 can flip to the syn conformation. With the recognition of the syn-form guanosine at position 36, the structures of the TrmD loops around G36 change, and the tRNA anticodon arm also undergoes a structural alteration to the “tight form.” The inward movement of the A38 sugar moiety provides space for the TrmD interdomain loop to fold into a helix just above G37 (state X).

TrmD traps the substrate tRNA tightly at this moment and is ready for the reaction. The methyl moiety of AdoMet is transferred to the N1 atom of G37 (state XI). After methyl transfer, the m1G37-modified tRNA and the other product, AdoHcy, are released from TrmD, accompanied by the collapse of the interdomain helix and the loosening of the knot structure. Finally, the resultant apo-form TrmD heads to the next round of the reaction. To facilitate the visualization of this TrmD enzymatic mechanism, a movie file is available (Movie S1).

The regions in direct contact with TrmD are strictly conserved in other TrmD substrate tRNAs, including the three H. influenzae tRNA transcripts analyzed in this study. Therefore, the overall enzymatic cycle is likely to be generally conserved. However, as described above, TrmD methylates the T. maritima transcript 2.2- to 99-fold more efficiently than the H. influenzae tRNA transcripts (rows A, E, F, and G in Table 1). Consequently, the tRNA sequences outside the direct contact regions—for example, the D and T arms—might influence the properties of the direct contact regions, and thus indirectly affect the reactivity of TrmD (“indirect readout” of the characteristics of tRNA substrates).

Why Do Bacteria Keep the 36GG37 Sequence in tRNAs?

It would seem easier for bacteria to replace the 36GG37 sequence in tRNANNG by the 36GA37 sequence, for preventing +1 frameshift errors. The fact that bacteria keep the 36GG37 sequence together with TrmD to synthesize m1G37 leads to the hypothesis that the N1-methylation status of G37 of the 36GG37-containing tRNAs functions to control gene expression. One interesting example in bacteria is that the +1 frameshift is used for the autogenous regulation of the translation of release factor 2 (RF-2), which functions to terminate translation at the UGA and UAA codons (21, 22). The early region of the RF-2 mRNA contains the in-frame UGA termination codon, as follows: UAU CUU UGAC UAC. When the RF-2 level is low, a tRNALeu with 36GG37 and lacking the m1G37 modification can shift into the +1 frame with the UUU codon, rather than the in-frame CUU codon at the P-site of the ribosome. This frameshift results in the translation of the GAC codon in the +1 frame to asparagine, as the residue next to the leucine. A lower level of RF-2 may be present because of slower bacterial growth and limiting metabolites (23, 24). The limiting metabolites include ATP and methionine, which would lead to reduced AdoMet levels and decreased synthesis of m1G37-tRNA by TrmD. Thereby, the lower levels of m1G37 would induce higher frequencies of +1 frameshifting of the tRNALeu, for translation of the full-length RF-2 protein. In other words, bacterial cells may use the synthesis of m1G37-tRNA to control the level of the +1 frameshift, and thus regulate gene expression.

Although TrmD synthesizes m1G37-tRNA in bacteria, a different enzyme, Trm5, performs the same enzymatic function in eukaryotes and archaea (25–28). The lack of homology between TrmD and Trm5—and the broad conservation of TrmD among bacterial species—have led to the focus on TrmD as a leading target for the next generation of antibiotics worthy of priority consideration (29). Potent inhibitors of TrmD, which are strong candidates for new antibiotic drugs, were recently reported (30). The present structural study provides the basis for designing robust and selective inhibitors of TrmD as a novel antimicrobial strategy.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Proteins and tRNA Transcripts.

The ORF of H. influenzae TrmD was cloned into the NdeI/XhoI sites of pET-28b(+), and the expressed protein has a His6-tag at the N terminus. E. coli strain Rosetta2 (DE3) was transformed by the recombinant plasmid and was cultured in LB medium. Protein synthesis was induced by adding isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside to a final concentration of 0.5 mM. Cells were cultured at 303 K for 5 h after induction and were harvested. The cells were lysed by sonication, and the debris was removed by centrifugation. The cleared lysate was purified by affinity chromatography using Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare), by ion-exchange column chromatography using RESOURCE Q or Mono Q (GE Healthcare), and by gel-filtration column chromatography using Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare). The purified TrmD protein was stored at 277 K in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 8.0), containing 100 mM NaCl and 5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol.

The site-directed mutations of the trmD gene were introduced using a PrimeSTAR Mutagenesis Basal Kit (Takara), and the mutants were purified in the same manner as wild-type TrmD.

All tRNA transcripts were prepared by in vitro transcription using T7 RNA polymerase, and the transcribed tRNAs were purified by RESOURCE Q ion-exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare). The purified and desalted tRNA transcripts were dissolved in 20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.6) buffer containing 5 mM MgCl2, heated at 353 K for 3 min, and then gradually cooled to room temperature for annealing.

Methylation Kinetics Analysis.

Steady-state kinetic analyses were performed according to the procedure described previously (31). Each tRNA sample (final concentration ranging from 0.1 to 80.0 µM, depending on the combination of the enzyme and the substrate tRNA) was denatured by heating at 85 °C for 3 min and annealed at 37 °C before use. The tRNA was mixed with a saturating amount of [3H-methyl]AdoMet (30 µM) in the reaction buffer, containing 0.1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 8.0, 4 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 6 mM MgCl2, 24 mM NH4Cl, and 0.024 mg/mL BSA, and then mixed with the H. influenzae TrmD enzyme (final concentration ranging from 0.02 to 5.0 µM). Aliquots were taken at various time points and precipitated by 5% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid on filter pads, and the amount of methyl transfer was determined by quantification of [3H] incorporation, using a scintillation counter. After correction of the quenching factor from filter precipitation, the initial rate at each tRNA concentration (pmole/min) was calculated and plotted as a function of the concentration. The data were fit to the Michaelis–Menten equation using the KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software), and the Km, kcat, and kcat/Km values for each tRNA and enzyme were calculated from the curve fitting.

Fluorescence Analysis of tRNA-Binding.

The interactions between sinefungin-bound TrmD and tRNAs were monitored by measuring the quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. The fluorescence was excited at 295 nm, and the emission was monitored at 310–400 nm at room temperature in fluorescence measurement buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl buffer (pH 8.0), containing 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10 μM sinefungin]. The TrmD dimer and tRNA variants were mixed to achieve final concentrations of 0.2 μM and 0–10 μM, respectively, and 750-μL samples were measured using a Spectrofluorometer FP-8500 (Jasco). The fluorescence intensities at 330 nm were used for the fittings. To obtain the dissociation constants for the first strong binding (Kd1) with the wild-type and G36A tRNAs, the quadratic equation was used for the fitting. The data did not reach a plateau within the tRNA concentration range. Additionally, the dissociation constants for the second binding with the wild-type and G36A tRNAs and those for the first and second bindings with the G36C and G36U tRNAs appeared unusually high. For these reasons, only the linear fits were applied, and the dissociation constants were not determined. Therefore, the equation for the wild-type and G36A tRNAs was,

| [1] |

and that for the G36C and G36U tRNAs was,

| [2] |

where F is the measured fluorescence signal intensity, F0 is the fluorescence signal intensity without the tRNAs, ΔF1 is the scale of the fluorescence signal change for the first strong binding, E is the total concentration of the TrmD dimer, A is the slope (the rate of the fluorescence signal change with respect to the tRNA concentration) for the weak binding, and T is the total concentration of tRNA. The data were fit to the above equations, using the KaleidaGraph software.

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Refinement.

For crystallizations of the TrmD•AdoMet and TrmD•sinefungin binary complexes, TrmD was concentrated to about 10 mg/mL, using an Amicon Ultra filter (Millipore). A 1.2-μL portion of the protein solution, supplemented with 1 mM AdoMet or sinefungin, was mixed with an equal volume of the reservoir solution, consisting of 0.8–0.85 M sodium citrate and 0.1 M N-cyclohexyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (pH 8.0–8.4). A crystallization drop was formed on an MRC-2 crystallization plate (Swissci) containing a 70-μL reservoir solution in the well, and was incubated at 293 K. Within a few days, crystals appeared in the drop. The crystals were flash-cooled with liquid nitrogen in a cryoprotectant reagent containing 25% (vol/vol) polyethylene glycol (PEG)-400.

For crystallization of the TrmD•tRNA•sinefungin ternary complex, equal volumes of the protein and tRNA solutions, at a molar ratio of 5:1, were mixed. This solution was concentrated using an Amicon Ultra filter (Millipore) to a final total concentration of about 5 mg/mL. A 1.2-μL portion of the sample solution, supplemented with 1 mM sinefungin, was mixed with 1.5-μL reservoir solution, containing 0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate (pH 4.6), 0.8 M ammonium phosphate monobasic, and 4% (wt/vol) PEG-20,000. The same crystallization plate as in the case of the binary complex was used and crystals appeared within a few days. The crystals were flash-cooled with liquid nitrogen in a cryoprotectant reagent containing 30% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol. The TrmD crystals in the complexes with the G37U or G37C tRNA variants were prepared by a similar method to that for the wild-type tRNA.

X-ray diffraction datasets were collected on beamlines at the Photon Factory (Ibaraki, Japan) and at SPring-8 (Hyogo, Japan), as described in Table S1. The datasets were processed with either the HKL-2000 software (32) or the XDS software (33). The initial phases were determined by the molecular-replacement method, using the program Phaser (34). The crystal structure of the apo-form of H. influenzae TrmD (PDB ID code 1UAJ) (3) was used as the search model for the structures of the TrmD•AdoMet and TrmD•sinefungin binary complexes. For solving the initial phase of the ternary complex with the wild-type T. maritima , the tertiary structures of the currently determined TrmD•sinefungin binary complex and the tRNA portion of the GluRS•tRNA complex (PDB ID code 3AKZ) (35) were used. The initial phases of the complex structures with the tRNA variants were calculated, using the coordinates of the currently determined ternary complex with the wild-type tRNA. The models were refined using the programs Coot (36), Refmac (37), CNS (38, 39), and Phenix (40). The dataset and refinement statistics, together with the Protein Data Bank accession codes, are provided in Table S1. The molecular graphics were prepared with the program PyMol (Schrödinger).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of the beamlines BL32XU and BL41XU at the SPring-8 and the beamlines BL-5A, AR-NW12A, and AR-NE3A at the Photon Factory for their support during data collection. This work was performed under the approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (Proposal 2011A1217), and that of the Photon Factory Program Advisory Committee (Proposal 2011G547). This work was supported by the Targeted Proteins Research Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, JSPS KAKENHI Grant 20247008 (to T.I. and S.Y.), and National Institutes of Health Grant GM081601 (to Y.-M.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 4YVG, 4YVH, 4YVI, 4YVJ, and 4YVK).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1422981112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Michel G, et al. The structure of the RlmB 23S rRNA methyltransferase reveals a new methyltransferase fold with a unique knot. Structure. 2002;10(10):1303–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00852-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nureki O, et al. An enzyme with a deep trefoil knot for the active-site architecture. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58(Pt 7):1129–1137. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902006601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn HJ, et al. Crystal structure of tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase: insights into tRNA recognition. EMBO J. 2003;22(11):2593–2603. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim K, et al. Structure of the YibK methyltransferase from Haemophilus influenzae (HI0766): A cofactor bound at a site formed by a knot. Proteins. 2003;51(1):56–67. doi: 10.1002/prot.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkins PA, et al. Insights into catalysis by a knotted TrmD tRNA methyltransferase. J Mol Biol. 2003;333(5):931–949. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anantharaman V, Koonin EV, Aravind L. SPOUT: A class of methyltransferases that includes spoU and trmD RNA methylase superfamilies, and novel superfamilies of predicted prokaryotic RNA methylases. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4(1):71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao Z, et al. Crystal structure of tRNA m1G9 methyltransferase Trm10: Insight into the catalytic mechanism and recognition of tRNA substrate. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(1):509–525. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byström AS, Björk GR. Chromosomal location and cloning of the gene (trmD) responsible for the synthesis of tRNA (m1G) methyltransferase in Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Gen Genet. 1982;188(3):440–446. doi: 10.1007/BF00330046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Björk GR, Wikström PM, Byström AS. Prevention of translational frameshifting by the modified nucleoside 1-methylguanosine. Science. 1989;244(4907):986–989. doi: 10.1126/science.2471265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Urbonavicius J, Qian Q, Durand JM, Hagervall TG, Björk GR. Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J. 2001;20(17):4863–4873. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Persson BC, Bylund GO, Berg DE, Wikström PM. Functional analysis of the ffh-trmD region of the Escherichia coli chromosome by using reverse genetics. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(19):5554–5560. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5554-5560.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li J, Esberg B, Curran JF, Björk GR. Three modified nucleosides present in the anticodon stem and loop influence the in vivo aa-tRNA selection in a tRNA-dependent manner. J Mol Biol. 1997;271(2):209–221. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas SR, Keller CA, Szyk A, Cannon JR, Laronde-Leblanc NA. Structural insight into the functional mechanism of Nep1/Emg1 N1-specific pseudouridine methyltransferase in ribosome biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(6):2445–2457. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wurm JP, et al. The ribosome assembly factor Nep1 responsible for Bowen-Conradi syndrome is a pseudouridine-N1-specific methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(7):2387–2398. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer B, et al. The Bowen-Conradi syndrome protein Nep1 (Emg1) has a dual role in eukaryotic ribosome biogenesis, as an essential assembly factor and in the methylation of Ψ1191 in yeast 18S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(4):1526–1537. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christian T, Lahoud G, Liu C, Hou YM. Control of catalytic cycle by a pair of analogous tRNA modification enzymes. J Mol Biol. 2010;400(2):204–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Christian T, Hou YM. Distinct determinants of tRNA recognition by the TrmD and Trm5 methyl transferases. J Mol Biol. 2007;373(3):623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakaguchi R, et al. Recognition of guanosine by dissimilar tRNA methyltransferases. RNA. 2012;18(9):1687–1701. doi: 10.1261/rna.032029.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi R, Lahoud G, Christian T, Gamper H, Hou YM. A divalent metal ion-dependent N1-methyl transfer to G37-tRNA. Chem Biol. 2014;21(10):1351–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lahoud G, et al. Differentiating analogous tRNA methyltransferases by fragments of the methyl donor. RNA. 2011;17(7):1236–1246. doi: 10.1261/rna.2706011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Craigen WJ, Cook RG, Tate WP, Caskey CT. Bacterial peptide chain release factors: Conserved primary structure and possible frameshift regulation of release factor 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(11):3616–3620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.11.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Craigen WJ, Caskey CT. Expression of peptide chain release factor 2 requires high-efficiency frameshift. Nature. 1986;322(6076):273–275. doi: 10.1038/322273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Enjalbert B, Letisse F, Portais JC. Physiological and molecular timing of the glucose to acetate transition in Escherichia coli. Metabolites. 2013;3(3):820–837. doi: 10.3390/metabo3030820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao KC, Tran LM, Liao JC. A global regulatory role of gluconeogenic genes in Escherichia coli revealed by transcriptome network analysis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(43):36079–36087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Björk GR, et al. A primordial tRNA modification required for the evolution of life? EMBO J. 2001;20(1-2):231–239. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goto-Ito S, et al. Crystal structure of archaeal tRNA(m1G37)methyltransferase aTrm5. Proteins. 2008;72(4):1274–1289. doi: 10.1002/prot.22019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goto-Ito S, Ito T, Kuratani M, Bessho Y, Yokoyama S. Tertiary structure checkpoint at anticodon loop modification in tRNA functional maturation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16(10):1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christian T, Evilia C, Williams S, Hou YM. Distinct origins of tRNA(m1G37) methyltransferase. J Mol Biol. 2004;339(4):707–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White TA, Kell DB. Comparative genomic assessment of novel broad-spectrum targets for antibacterial drugs. Comp Funct Genomics. 2004;5(4):304–327. doi: 10.1002/cfg.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill PJ, et al. Selective inhibitors of bacterial t-RNA-(N1G37) methyltransferase (TrmD) that demonstrate novel ordering of the lid domain. J Med Chem. 2013;56(18):7278–7288. doi: 10.1021/jm400718n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christian T, Evilia C, Hou YM. Catalysis by the second class of tRNA(m1G37) methyl transferase requires a conserved proline. Biochemistry. 2006;45(24):7463–7473. doi: 10.1021/bi0602314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito T, Yokoyama S. Two enzymes bound to one transfer RNA assume alternative conformations for consecutive reactions. Nature. 2010;467(7315):612–616. doi: 10.1038/nature09411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 4):486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vagin AA, et al. REFMAC5 dictionary: Organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brunger AT. Version 1.2 of the crystallography and NMR system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(11):2728–2733. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54(Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66(Pt 2):213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gouet P, Courcelle E, Stuart DI, Métoz F. ESPript: Analysis of multiple sequence alignments in PostScript. Bioinformatics. 1999;15(4):305–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.4.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nureki O, et al. Deep knot structure for construction of active site and cofactor binding site of tRNA modification enzyme. Structure. 2004;12(4):593–602. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leulliot N, Bohnsack MT, Graille M, Tollervey D, Van Tilbeurgh H. The yeast ribosome synthesis factor Emg1 is a novel member of the superfamily of alpha/beta knot fold methyltransferases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(2):629–639. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor AB, et al. The crystal structure of Nep1 reveals an extended SPOUT-class methyltransferase fold and a pre-organized SAM-binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(5):1542–1554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.