Significance

Much attention has been recently paid to the role of intestinal epithelial cells in the homeostatic regulation of intestinal immunity. Here we show that ablation of stomach-cancer–associated protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SAP-1) markedly increased the severity of colitis in interleukin (IL)-10–deficient mice, suggesting that SAP-1 protects against colitis in a cooperative manner with IL-10. We also identify carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule (CEACAM) 20, an intestinal microvilli-specific membrane protein, as a dephosphorylation target for SAP-1. Indeed, tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 promotes the binding of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), thereby inducing production of chemokines such as IL-8. Thus, we propose a mechanism by SAP-1 and CEACAM20 in the intestinal epithelium for regulation of the intestinal immunity.

Keywords: colitis, intestinal epithelial cells, intestinal immunity, protein tyrosine phosphatase

Abstract

Intestinal epithelial cells contribute to regulation of intestinal immunity in mammals, but the detailed molecular mechanisms of such regulation have remained largely unknown. Stomach-cancer–associated protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SAP-1, also known as PTPRH) is a receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase that is localized specifically at microvilli of the brush border in gastrointestinal epithelial cells. Here we show that SAP-1 ablation in interleukin (IL)-10–deficient mice, a model of inflammatory bowel disease, resulted in a marked increase in the severity of colitis in association with up-regulation of mRNAs for various cytokines and chemokines in the colon. Tyrosine phosphorylation of carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule (CEACAM) 20, an intestinal microvillus-specific transmembrane protein of the Ig superfamily, was greatly increased in the intestinal epithelium of the SAP-1–deficient animals, suggesting that this protein is a substrate for SAP-1. Tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 by the protein tyrosine kinase c-Src and the consequent association of CEACAM20 with spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) promoted the production of IL-8 in cultured cells through the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). In addition, SAP-1 and CEACAM20 were found to form a complex through interaction of their ectodomains. SAP-1 and CEACAM20 thus constitute a regulatory system through which the intestinal epithelium contributes to intestinal immunity.

Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) play a central role in food digestion and absorption of nutrients, water, and electrolytes. They also contribute to the regulation of intestinal immunity by subserving two main functions (1). First, the single layer of IECs provides a physical barrier that protects the lamina propria as well as the inner body from the external environment, which includes the vast array of microbes present in the intestinal lumen. This barrier function of IECs is achieved through intercellular adhesion mediated by tight junctions, adherens junctions, and desmosomes (2). Indeed, mice deficient in the tight-junction component JAM-A manifest increased paracellular permeability and inflammation in the intestine (3). Moreover, forced expression of a dominant negative mutant of N-cadherin, which attenuated expression of endogenous E-cadherin, a major component of adherens junctions, also resulted in colonic inflammation in mice (4). The importance of the epithelial barrier for intestinal immunity is further supported by the finding of abnormal intestinal permeability in first-degree relatives of individuals with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease (5).

The second function of IECs related to regulation of intestinal immunity is the production of a variety of antimicrobial peptides—such as α- and β-defensin, which are produced by Paneth cells and prevent the growth of pathogenic microbes (6)—as well as of mucus, which is produced mostly by goblet cells. Indeed, a reduced level of α-defensin in the intestine is frequently associated with Crohn’s disease (7). In addition, homozygous mutations of nucleotide oligomerization domain protein 2 (Nod2), an intracellular receptor for muramyl dipeptide, are highly associated with the incidence of Crohn’s disease (8), with Nod2 also having been found to promote expression of the defensin-related cryptdins (9). The importance of Paneth cells for regulation of intestinal immunity was further revealed by the observation that ablation of the transcription factor XBP1 in IECs resulted in a loss of Paneth cells as well as development of enteritis in mice (10). Mucin2 (Muc2) is the most abundant mucin of intestinal mucus, and ablation of Muc2 in mice was found to result in the spontaneous development of colitis (11, 12). In contrast to such a role for IECs in protection against colitis, IECs are thought to contribute to the development of inflammatory infiltrates by producing chemokines, such as interleukin (IL)-8 in humans or its homologs keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) in mice (13, 14). Moreover, proper turnover of IECs through regulation of cell death was shown to be important for homeostasis of intestinal immunity (15, 16). However, the detailed molecular mechanisms by which IECs regulate intestinal immunity have remained poorly elucidated.

Stomach-cancer–associated protein tyrosine phosphatase 1 (SAP-1, also known as PTPRH) is a receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) with a single catalytic domain in its cytoplasmic region and multiple fibronectin type III-like domains in its extracellular region (17). It was previously shown to be localized specifically to microvilli of the brush border in epithelial cells of the small intestine and stomach in mice (18). SAP-1–deficient mice manifest no marked changes in the morphology of the small intestinal epithelium (18), suggesting that SAP-1 is not important for determination of the cellular architecture of this tissue. Moreover, SAP-1 is dispensable for regulation of food digestion and absorption of nutrients and electrolytes in the intestine. In contrast, forced expression of SAP-1 in cultured cells was shown to inhibit cell proliferation, an effect mediated in part by attenuation of growth-factor–induced mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation or by induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis (19, 20). We have now investigated the potential role of SAP-1 in the regulation of intestinal immunity by IECs.

Results

Impact of SAP-1 Ablation on Development of Colitis in IL-10–Deficient Mice.

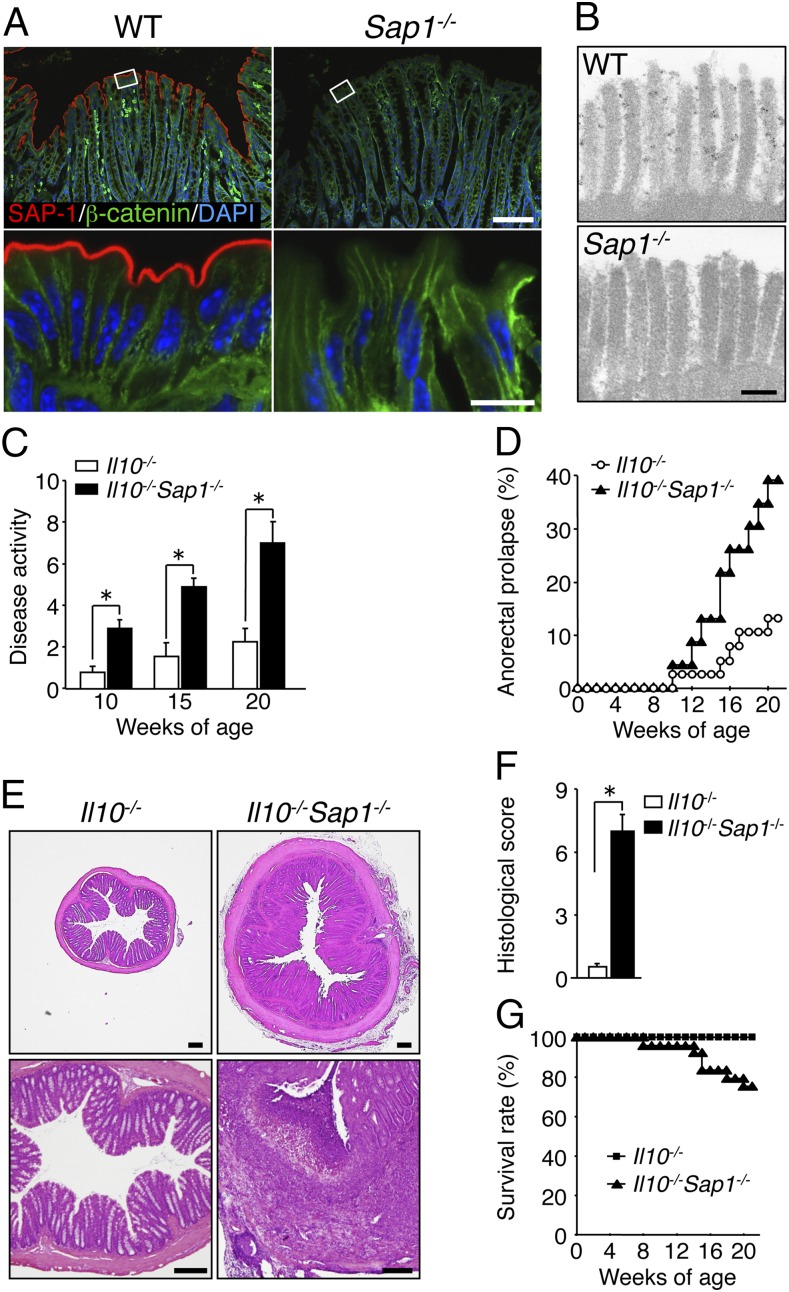

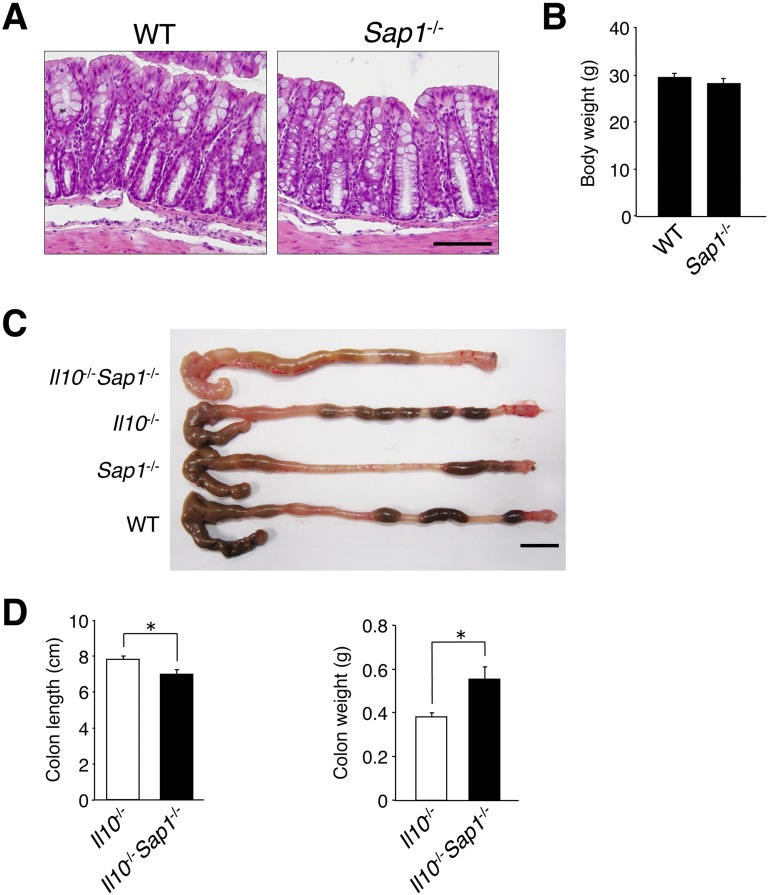

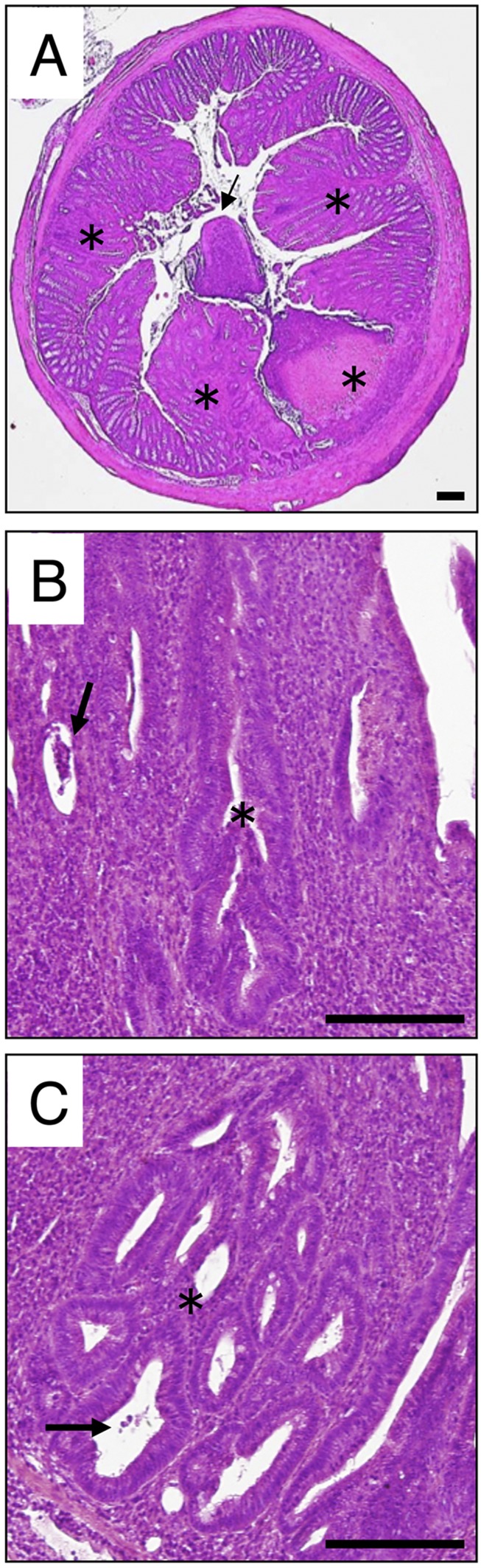

SAP-1 was previously shown to be localized specifically to microvilli of the brush border in epithelial cells of the small intestine and stomach of mice (18). Immunohistofluorescence analysis showed that SAP-1 is also localized at the apical surface of colonic epithelial cells in the mouse (Fig. 1A). In addition, immunoelectron microscopy revealed prominent SAP-1 staining at the microvilli of epithelial cells in the colon (Fig. 1B). In contrast, SAP-1 immunoreactivity was virtually undetectable in the colon of SAP-1–deficient (Sap1−/−) mice (Fig. 1 A and B), indicating that SAP-1 is indeed expressed in the microvilli of colonic epithelial cells. Not only intestinal immune cells but also IECs are thought to contribute to intestinal immunity (1). However, Sap1−/− mice up to 20 wk of age did not exhibit any sign of colonic inflammation, as judged on the basis of both clinical manifestations such as bloody stool or weight loss as well as histological examination (Fig. S1 A and B). We therefore crossed Sap1−/− mice with IL-10–deficient (Il10−/−) mice, a model of human IBD such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis (21, 22) and examined the impact of SAP-1 ablation on the severity of spontaneous colitis in these latter mice. We first monitored disease activity, which was scored on the basis of stool consistency, blood in the stool, and anorectal prolapse, in Il10−/− and Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice at 10, 15, and 20 wk of age. Disease activity in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice (male and female) at 10–20 wk of age was markedly increased compared with that in Il10−/− mice (Fig. 1C). In particular, the incidence of anorectal prolapse was greatly increased in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice compared with Il10−/− mice (Fig. 1D). The colon of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice at 20 wk of age showed signs of severe colitis, including pronounced thickening of the bowel wall, a shortened colonic length, and unformed or absent stools, compared with Il10−/−, Sap1−/−, or wild type (WT) mice (Fig. S1 C and D). Microscopic examination revealed that the thickness of the colonic mucosa in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice at 20 wk of age was markedly increased compared with that in Il10−/− mice (Fig. 1E). In addition, severe epithelial hyperplasia, crypt distortion, crypt abscesses, and microadenoma were apparent in the colon of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice (Fig. S2). The histological score for colonic inflammation was thus significantly greater for Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice than for Il10−/− mice (Fig. 1F). Finally, the survival rate of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice was substantially reduced compared with that of Il10−/− mice (Fig. 1G). Collectively, these observations thus suggested that SAP-1 ablation results in exacerbation of spontaneous colitis in Il10−/− mice.

Fig. 1.

Impact of SAP-1 ablation on development of colitis in IL-10–deficient mice. (A) Cryostat sections of the colon of WT or Sap1−/− mice at 6 wk of age were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies to SAP-1 (red) and to β-catenin (green). Nuclei were also stained with DAPI (blue). Boxed regions (Upper) are shown at higher magnification (Lower). [Scale bars, 100 μm (Upper) or 10 μm (Lower).] (B) Immunoelectron microscopy of the colonic epithelium of adult WT or Sap1−/− mice with antibodies to SAP-1. (Scale bar, 200 nm.) (C) Disease activity for colitis in 10-, 15-, or 20-wk-old Il10−/− (n = 35, 18, and 19, respectively) or Il10−/−Sap1−/− (n = 40, 24, and 24, respectively) mice. *P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney u test). (D) Incidence of anorectal prolapse in Il10−/− (n = 38) or Il10−/−Sap1−/− (n = 23) mice. (E) H&E staining of midcolon sections from 20-wk-old Il10−/− or Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. (Scale bars, 200 μm.) (F) Histological score for inflammation in the colon of 20-wk-old Il10−/− or Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. *P < 0.05 (Mann–Whitney u test). (G) Survival rates of Il10−/− (n = 36) and Il10−/−Sap1−/− (n = 24) mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments (A, B, and E) and pooled from at least three independent experiments (C, D, and G); means ± SEM in C, or are from one representative experiment (F; means ± SEM for a total of five mice for each genotype).

Fig. S1.

Characteristics of the colon of Il10−/−Sap1−/−, Il10−/−, Sap1−/−, or WT mice. (A) Sections of the colon of WT or Sap1−/− littermates at 20 wk of age were stained with Mayer’s H&E. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (B) Body weight of male WT or Sap1−/− mice at 20 wk of age. (C) Gross appearance of the colon from mice of the indicated genotypes at 20 wk of age. (Scale bar, 10 mm.) (D) The length (Left) and weight (Right) of the colon of Il10−/− and Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice were measured at 20 wk of age. Data are representative of two independent experiments (A and C) and are from one representative experiment [B and D; means ± SEM for a total of three (B) or five (D) mice for each genotype]. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t test).

Fig. S2.

H&E staining of cross-sections prepared from the midcolon of 20-wk-old Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. (A–C) Multifocal lesions (asterisks in A), exudates in the lumen (arrow in A), erosion with crypt abscesses (arrows in B and C), crypt distortion (asterisk in B), and microadenoma (asterisk in C) were observed. (Scale bars, 200 μm.)

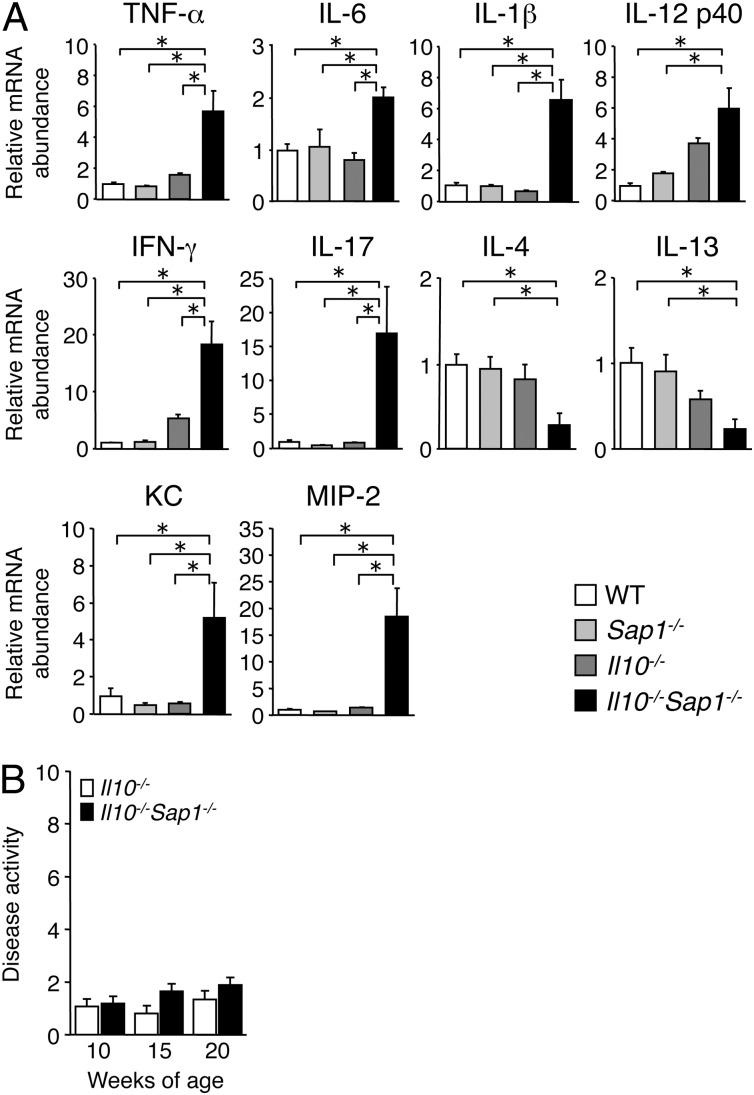

Consistent with the extent of colonic inflammation, quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis revealed that the amounts of mRNAs for proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-12 were markedly increased in the colonic mucosa of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice at 10 wk of age compared with those in Il10−/−, Sap1−/−, or WT mice (Fig. 2A). The abundance of mRNAs for interferon γ (IFN-γ) and IL-17, both of which are implicated in development of colitis in IL-10–deficient mice (22, 23), was also increased in the colonic mucosa of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice (Fig. 2A). Conversely, the amounts of mRNAs for the T helper 2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 were decreased in the double-mutant animals. The expression of chemokine genes such as those for KC and MIP-2 in the colonic mucosa was greatly up-regulated in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice compared with the other three strains (Fig. 2A). These results thus further suggested that SAP-1, together with IL-10, protects against the development of colitis. Commensal bacteria are implicated in the development of colitis in IL-10–deficient mice (21, 24). We therefore next examined the role of commensal bacteria in the exacerbation of colitis in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. Mice were given a combination of broad-spectrum antibiotics in drinking water beginning at 4 wk of age to deplete commensal bacteria. Such depletion largely prevented the development of colitis in both Il10−/−Sap1−/− and Il10−/− mice at 10–20 wk of age, with scores for disease activity in the two strains being similar (Fig. 2B). These results suggested that commensal bacteria are important for the increase in the severity of spontaneous colitis induced by SAP-1 ablation in Il10−/− mice.

Fig. 2.

Altered cytokine and chemokine mRNA abundance in the colon of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice as well as the effect of antibiotic treatment on colitis development. (A) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of cytokine and chemokine mRNAs in the colon of 10-wk-old WT, Sap1−/−, Il10−/−, or Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. The amount of each mRNA was normalized by that of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) mRNA and then expressed relative to the normalized value for WT mice. *P < 0.05 (ANOVA and Tukey’s test). (B) Il10−/− (n = 15) and Il10−/−Sap1−/− (n = 17) mice were treated with antibiotics from 4 wk of age, and disease activity for colitis was determined at 10, 15, and 20 wk of age. Data are from one representative experiment (A; means ± SEM for a total of five mice for each genotype) or are pooled from at least three independent experiments (B; means ± SEM).

Identification of Carcinoembryonic Antigen-Related Cell Adhesion Molecule (CEACAM) 20 as a Tyrosine-Phosphorylated Protein in the Intestinal Epithelium of SAP-1–Deficient Mice.

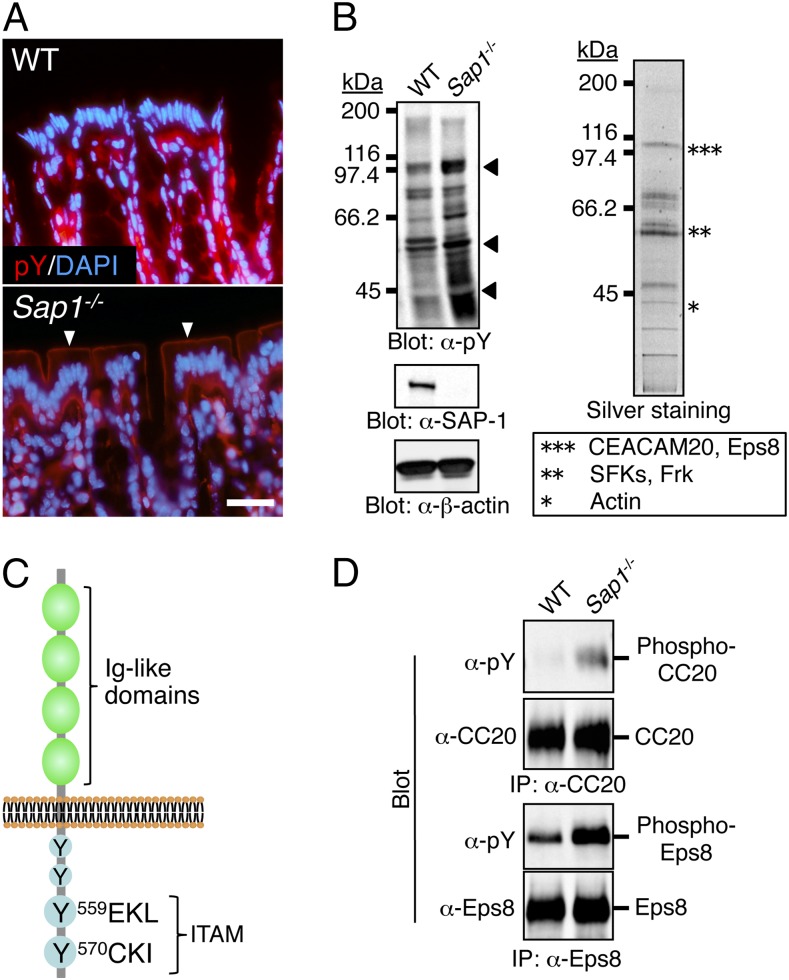

We further investigated the molecular mechanism by which ablation of SAP-1 exacerbates colitis in Il10−/− mice. SAP-1 was previously shown to inhibit the proliferation of cultured cells (19, 20). However, cell turnover, morphology of intercellular junctions, and paracellular permeability in the colonic epithelium did not differ between WT and Sap1−/− mice (Fig. S3). In addition, the number of goblet cells or Paneth cells, which are thought to protect against colitis by secreting mucus or antimicrobial peptides, respectively, in the intestinal epithelium did not differ between the two strains (Fig. S4). In contrast, immunohistofluorescence analysis with antibodies to phosphotyrosine revealed that staining was markedly increased along the apical surface of colonic epithelial cells in Sap1−/− mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 3A). Consistent with this observation, immunoblot analysis of isolated microvillus membranes from the small intestine with the same antibodies showed that the levels of tyrosine phosphorylation of several proteins (molecular sizes of ∼40 to ∼110 kDa) were increased in Sap1−/− mice (Fig. 3B). Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were affinity purified from the solubilized microvillus membrane fraction of Sap1−/− mice with the use of agarose beads conjugated with the antibodies to phosphotyrosine and were then visualized by silver staining of SDS/PAGE gels (Fig. 3B). Bands corresponding to ∼100-, ∼60-, and ∼40-kDa proteins were excised, enzymatically digested, and subjected to mass spectrometry (MS). Several peptide fractions were obtained for each protein band, and the molecular size of these peptides was determined by MALDI-TOF MS. Comparison of the determined molecular sizes with theoretical peptide masses for proteins registered in the nonredundant database in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBInr) indicated that the ∼100-kDa protein band contained CEACAM20 and epidermal growth factor receptor kinase substrate 8 (Eps8) (Fig. 3B). In addition, the ∼60-kDa protein band contained several Src family kinase SFKs (Lyn, c-Yes, Lck, c-Src, and c-Fgr) as well as the SFK-related protein Frk (Fig. 3B).

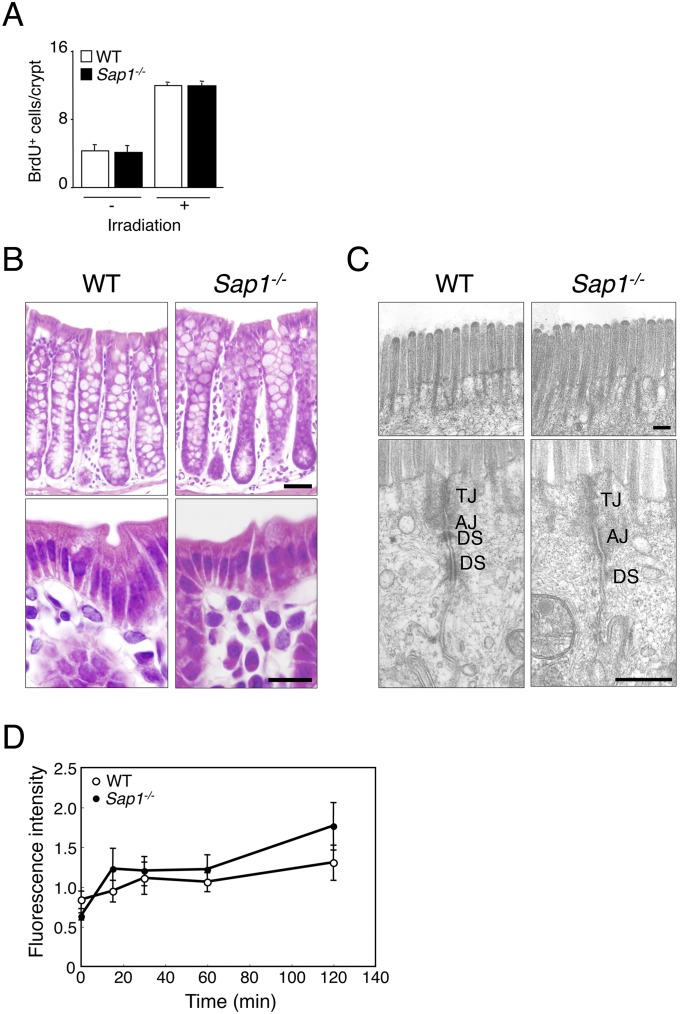

Fig. S3.

Turnover and morphology of colonic epithelial cells in WT or Sap1−/− mice and lack of effect of SAP-1 ablation on paracellular permeability of the colonic epithelium. (A) Colonic epithelial cell turnover in WT or Sap1−/− mice was assessed with a BrdU incorporation assay. Adult mice that had been subjected (or not) to irradiation (total of 10 Gy) were injected i.p. with BrdU (50 mg/kg), 2 h after which the colon was removed, fixed, immunostained with antibodies to BrdU and secondary antibodies labeled with Cy3, and examined by confocal fluorescence microscopy. The number of BrdU-positive cells in 12 crypts per animal was counted, and the average number per crypt was determined. (B) Sections of the colon of WT or Sap1−/− littermates at 10 wk of age were stained with Mayer’s H&E. The images show intestinal glands (Upper) or the epithelium (Lower). [Scale bars, 50 μm (Upper) or 10 μm (Lower).] (C) Transmission electron microscopy of the colon samples shown in B. Images of the microvilli (Upper) and of the upper region of cell–cell adhesion in the epithelium (Lower) are shown. AJ, adherens junction; DS, desmosome; TJ, tight junction. (Scale bars, 200 nm.) (D) Colonic paracellular permeability was measured with the use of an in situ closed-loop system. WT or Sap1−/− mice at 12–16 wk of age were anesthetized, and the colon was exposed by an abdominal midline incision. FITC-dextran with an average molecular weight of 4,400 (FD4) was injected into the lumen of a closed loop of the colon, and the fluorescence intensity of FD4 in plasma was measured at the indicated times thereafter. The paracellular permeability of the colonic epithelium did not differ between WT and Sap1−/− mice. Data are from one representative experiment [A and D; means ± SEM three (A) or four (D) mice for each genotype] and are representative of at least two independent experiments (B and C).

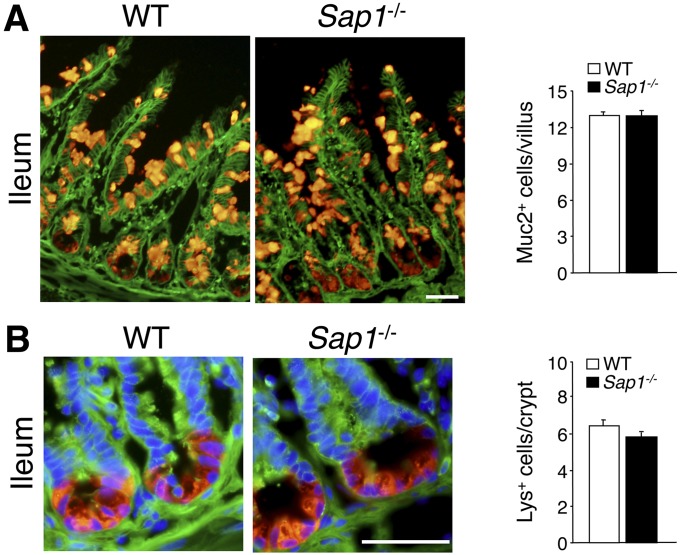

Fig. S4.

Lack of effect of SAP-1 ablation on the number of goblet cells or Paneth cells in the small intestine. Cryostat sections of the ileum of adult WT or Sap1−/− mice were subjected to immunofluorescence analysis with antibodies to β-catenin (green) (A and B) as well as with antibodies to Muc2 (red) (A) or to lysozyme (red) (B). Nuclei were also stained with DAPI (blue) in (B). (Scale bars, 50 μm.) The numbers of Muc2-positive goblet cells per villus (A) and lysozyme-positive (Lys+) Paneth cells per crypt (B) were determined, revealing no differences between the two genotypes. Quantitative data are means ± SEM for 32 (WT) or 26 (Sap1−/−) villi (A) or for 44 (WT) or 39 (Sap1−/−) crypts (B) from a total of two mice per genotype.

Fig. 3.

Identification of CEACAM20 as a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein in the intestinal epithelium of SAP-1–deficient mice. (A) Sections of the colon of 10-wk-old WT or Sap1−/− mice were stained with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (pY, red) and with DAPI (blue). (Scale bar, 20 μm.) Arrowheads indicate prominent staining for phosphotyrosine along the apical surface of the colonic epithelium in the mutant. (B) Microvillus membranes prepared from the entire small intestine of WT or Sap1−/− mice were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (α-pY), to SAP-1, or to β-actin (Left). Bands corresponding to proteins whose level of tyrosine phosphorylation was markedly increased in Sap1−/− mice are indicated by arrowheads. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins purified from a solubilized microvillus membrane fraction of Sap1−/− mice with the use of agarose-bead–conjugated antibodies to phosphotyrosine were fractionated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by silver staining (Right). The protein bands indicated by the asterisks were analyzed by MS. The ∼100-, ∼60-, and ∼40-kDa protein bands (***, **, and *) contained the indicated proteins. (C) Schematic representation of the structure of mouse CEACAM20 showing four Ig-like domains in the extracellular region and four potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites, two of which constitute an ITAM, in the cytoplasmic region. (D) Microvillus membranes prepared from the entire small intestine of WT or Sap1−/− mice were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to CEACAM20 (α-CC20) or to Eps8, and the resulting precipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis of phosphotyrosine, CEACAM20, or Eps8. Data are representative of three (A) or two (B and D) independent experiments.

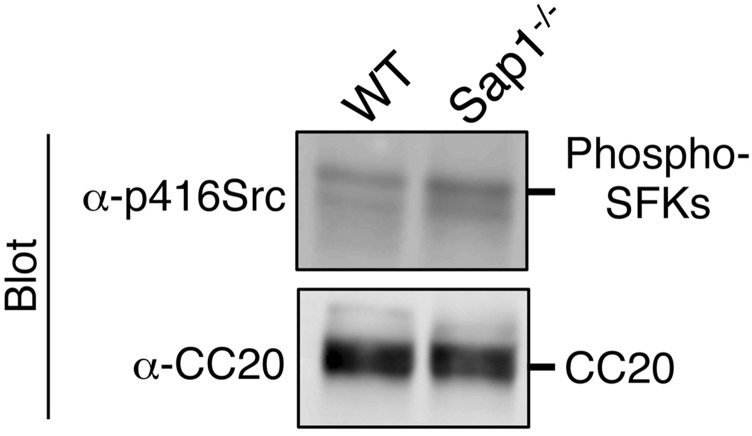

On the basis of its cDNA sequence, CEACAM20 is predicted to be a transmembrane protein that possesses four Ig-like domains in its extracellular region as well as four potential tyrosine phosphorylation sites in its cytoplasmic region, with the two COOH-terminal tyrosine residues (Tyr559 and Tyr570) and their surrounding sequence corresponding well to the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) (25) (Fig. 3C). Immunoprecipitation with antibodies to mouse CEACAM20 showed that the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of this protein was indeed increased in the microvillus membrane fraction of Sap1−/− mice compared with that apparent for WT mice (Fig. 3D). These results thus suggested that CEACAM20 is a substrate for the PTP activity of SAP-1 in the intestinal epithelium. In contrast, the phosphorylation of Tyr416 of c-Src (26) as well as the tyrosine phosphorylation of other SFKs in microvillus membranes did not differ substantially between Sap1−/− and WT mice (Fig. S5). The extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of Eps8 was also increased in microvillus membranes of Sap1−/− mice compared with that apparent for WT mice (Fig. 3D). However, given that the abundance of Ceacam20 mRNA, like that of Sap1 mRNA, was previously found to be highest in the intestine (18, 25), whereas Eps8 is expressed ubiquitously (27), we pursued the further characterization of CEACAM20 as a potential substrate for SAP-1 in the intestinal epithelium.

Fig. S5.

Lack of effect of SAP-1 ablation on tyrosine phosphorylation of SFKs in microvillus membrane fraction. (A) Microvillus membranes prepared from the entire small intestine of WT or Sap1−/− mice were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to phospho-Src family kinases (p416Src), or to CEACAM20. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Colocalization of CEACAM20 and SAP-1 in the Intestinal Epithelium.

We next examined the localization and function of CEACAM20. Immunoblot analysis of various mouse tissues showed that the abundance of CEACAM20 was highest in the small intestine and colon, being minimal or low in other tissues (Fig. 4A). This expression pattern of CEACAM20 is essentially identical to that of SAP-1 (Fig. 4A) (18). Immunohistofluorescence analysis revealed that staining for CEACAM20 was localized at the apical surface of the colon and largely overlapped with that of SAP-1 (Fig. 4B). Immunoreactivity for CEACAM20 was detected immediately above prominent staining for F-actin, likely corresponding to the terminal web (2), at the brush border of colonic epithelial cells (Fig. 4B). These results thus indicated that CEACAM20 is expressed specifically in microvilli of colonic epithelial cells, where it colocalizes with SAP-1.

Fig. 4.

Colocalization of CEACAM20 and SAP-1 in the intestinal epithelium. (A) Lysates of the indicated adult WT mouse tissues were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to CEACAM20 (α-CC20), and the resulting precipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the same antibodies (Left). Lysates of mouse stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon were also subjected to immunoblot analysis of CEACAM20, SAP-1, or β-tubulin (Right). (B) Sections of the colonic epithelium of 8-wk-old WT mice were stained with antibodies to CEACAM20 and to SAP-1, with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin for detection of F-actin, and with DAPI, as indicated. Boxed regions (Middle Right) are shown at higher magnification at Right. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (C) HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for SAP-1(WT) and Myc-epitope–tagged CEACAM20(WT) [MycCC20(WT)], or for mutant versions of each protein lacking the cytoplasmic region (ΔCP), as indicated, were lysed in a cell lysis buffer containing n-octyl-β-D-glucoside (ODG buffer) as described in the SI Materials and Methods section and subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. (D) HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for SAP-1(WT) and CEACAM1(WT) [CC1(WT)] were lysed in ODG buffer and subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. Total cell lysates were also subjected directly to immunoblot analysis. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

Coexpression of SAP-1 and Myc epitope-tagged CEACAM20 in HEK293A cells also revealed that the two proteins coimmunoprecipitated with each other (Fig. 4C). Such complex formation was also apparent when mutant versions of either or both proteins that lack the cytoplasmic region were coexpressed (Fig. 4C). By contrast, the association of SAP-1 with CEACAM1, another CEACAM family member expressed in colonic epithelial cells (28), was not detected in HEK293A cells overexpressing these two proteins (Fig. 4D). These results suggested that SAP-1 specifically interacts with CEACAM20 and that this interaction is mediated via the ectodomains of both proteins.

Tyrosine Phosphorylation of CEACAM20 by SFKs and Its Association with Spleen Tyrosine Kinase (Syk).

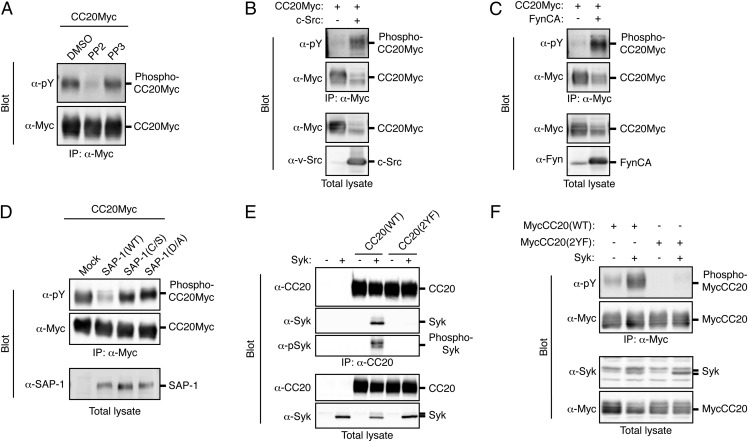

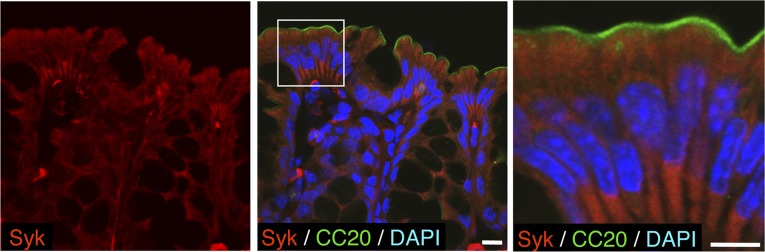

Given that CEACAM20 was identified as a potential substrate for SAP-1 and was found to colocalize with SAP-1 in colonic epithelial cells, we further investigated the properties of this protein. Consistent with the presence of putative tyrosine phosphorylation sites in its cytoplasmic region (Fig. 3C), we found that forced expression of CEACAM20 tagged with the Myc epitope in HEK293A cells resulted in tyrosine phosphorylation of the overexpressed protein and that such phosphorylation was prevented by treatment of the cells with PP2, an inhibitor of SFKs, but not by that with PP3, an inactive PP2 analog (Fig. 5A). In addition, coexpression of c-Src or an activated form of the tyrosine kinase Fyn together with CEACAM20 in HEK293A cells markedly enhanced the tyrosine phosphorylation of the latter protein (Fig. 5 B and C), suggesting that SFKs play a role in the tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20. Expression of SAP-1, but not that of its catalytically inactive mutants SAP-1(C/S) or SAP-1(D/A), reduced the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 in transfected cells (Fig. 5D). Incubation of tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 in vitro with a glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein containing the cytoplasmic domain of SAP-1 [GST–SAP-1(WT)], but not that with GST–SAP-1(C/S), resulted in its efficient dephosphorylation (Fig. S6), further suggesting that CEACAM20 is likely a substrate for SAP-1. The ITAM of CEACAM20 contains Y559EKL and Y570CKI sequences (Fig. 3C), which correspond well to sequences previously shown to serve when phosphorylated as a binding site for the SH2 domains of the tyrosine kinase Syk or SFKs (29, 30). Indeed, coexpression of CEACAM20 and Syk in HEK293A cells resulted in the association of the two proteins as well as in a marked increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of Syk, whereas a mutant of CEACAM20 [CEACAM20(2YF)] in which Tyr559 and Tyr570 are replaced with Phe failed to form a complex with Syk (Fig. 5E). A GST fusion protein containing the two SH2 domains of Syk also bound to tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20(WT) but not to CEACAM20(2YF) in vitro (Fig. S7A). In contrast, tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 failed to bind to c-Src or Fyn as well as to the SFK-related protein Frk (Fig. S7 B–D), the latter of which is highly expressed in the intestine (31). Furthermore, coexpression of Syk with CEACAM20(WT) [but not that with CEACAM20(2YF)] resulted in an increase in the level of tyrosine phosphorylation of the latter protein (Fig. 5F). These data thus suggested that tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 specifically binds to the SH2 domains of Syk and thereby activates this kinase, which in turn mediates the further tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20. Immunohistofluorescence analysis showed that Syk was indeed present in the cytoplasm of colonic epithelial cells (Fig. S8).

Fig. 5.

Tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 by SFKs and its association with Syk. (A) HEK293A cells expressing Myc-epitope–tagged CEACAM20 (CC20Myc) were treated with 10 μM PP2 or PP3 (or with DMSO vehicle) for 30 min, after which cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to Myc and the resulting precipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to Myc or to phosphotyrosine (α-pY). (B and C) Lysates of HEK293A cells transfected with an expression vector for CC20Myc together with either an expression vector for c-Src (B), an active mutant of Fyn [Fyn CA] (C), or the corresponding empty vector (B and C) were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis as in A. Total cell lysates were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to Myc (B and C), to v-Src (B), or to Fyn (C). (D) Lysates of HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis as in A. Total cell lysates were also subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to SAP-1. (E) Lysates of HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to CEACAM20 (α-CC20), and the resulting precipitates as well as the original cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to CEACAM20, to Syk, or to phosphorylated Syk (α-pSyk). (F) Lysates of HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to Myc, and the resulting precipitates as well as the original cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. S6.

Dephosphorylation of tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 by SAP-1 in vitro. Myc-epitope–tagged CEACAM20 (CC20Myc)-expressing HEK293A cells were treated with 100 μM sodium pervanadate for 5 min and then subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with antibodies to Myc. The resulting precipitates were incubated with GST, GST–SAP-1(WT), or GST–SAP-1(C/S) for 20 min at 30 °C and then subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to phosphotyrosine (α-pY) or to Myc. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. S7.

Tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 binds to the SH2 domains of Syk and no interaction of CEACAM20 with c-Src, Fyn, or Frk. (A) Lysates of pervanadate-treated HEK293A cells expressing MycCC20(WT) or MycCC20(2YF) were incubated with GST or a GST fusion protein containing the SH2 domains of Syk immobilized to glutathione-agarose beads, after which the bead-bound proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis with antibodies to CEACAM20 (Upper). The same amount of the lysates (input) was also subjected directly to immunoblot analysis (Lower Left). The purity of the GST proteins used in the assay was demonstrated by SDS/PAGE and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) (Lower Right). (B–D) Lysates of HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to Myc, and the resulting precipitates as well as the original cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with the indicated antibodies. All data are representative of three independent experiments.

Fig. S8.

Expression of Syk in the colonic epithelium. A cryostat section of the colon of a WT mouse was subjected to immunofluorescence staining with antibodies to Syk (red) and to CEACAM20 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The boxed region (Middle) is shown at higher magnification at Right. [Scale bars, 10 μm (Middle) or 5 μm (Right).] Images are representative of three independent experiments.

CEACAM20 Promotes Chemokine Production Through Activation of Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB).

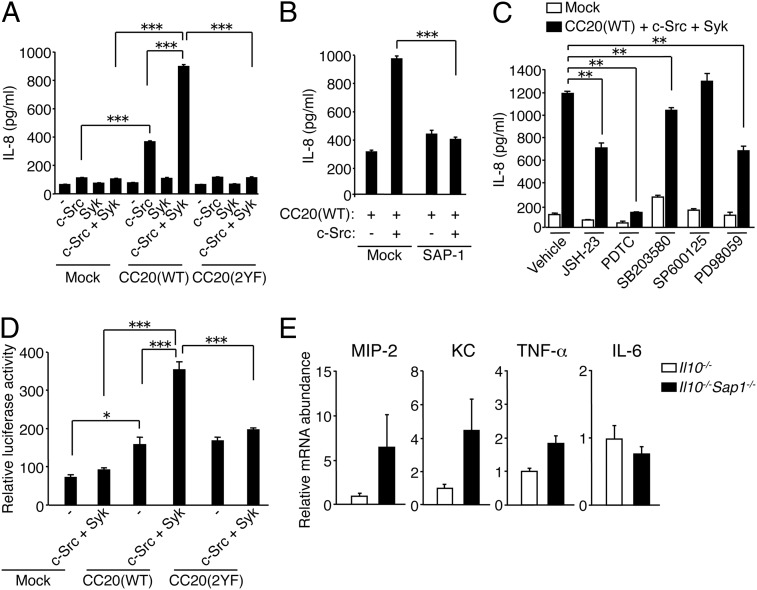

IECs contribute to the regulation of intestinal immunity by producing chemokines such as IL-8, KC, and MIP-2 that promote inflammatory infiltration, in particular that of neutrophils (13, 14). We therefore examined whether CEACAM20 together with c-Src and Syk might promote chemokine production. Forced expression of CEACAM20 with c-Src in HEK293A cells (which express endogenous Syk) (Fig. 5 E and F) resulted in a significant increase in IL-8 production compared with that observed in cells expressing either protein alone (Fig. 6A). This effect of CEACAM20 and c-Src was further enhanced by coexpression of Syk (Fig. 6A). By contrast, forced expression of CEACAM20(2YF) together with c-Src and Syk had no effect on IL-8 production (Fig. 6A). In addition, coexpression of SAP-1 markedly attenuated the increase in IL-8 production induced by expression of CEACAM20 and c-Src (Fig. 6B). These results suggested that tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 and its association with Syk in the presence of c-Src promote IL-8 production, whereas SAP-1 counteracts this effect.

Fig. 6.

CEACAM20 promotes chemokine production through activation of NF-κB. (A–C) HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were cultured for 24 h in the absence (A and B) or presence (C) of either DMSO (vehicle), NF-κB inhibitors (JSH-23 or PDTC), a p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580), a JNK inhibitor (SP600125), or a MEK inhibitor (PD98059). The concentration of IL-8 in the culture supernatants was then determined. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA and Tukey’s test). (D) HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins together with an NF-κB reporter plasmid and internal control plasmid were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA and Tukey’s test). (E) Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNAs for MIP-2, KC, TNF-α, and IL-6 in colonic epithelial cells isolated from 6- to 8-wk-old Il10−/− or Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice. The amount of each mRNA was normalized by that of Gapdh mRNA and then expressed relative to the normalized value for Il10−/− mice. Data are representative of three independent experiments (A–D; means ± SEM of triplicates for each condition) or are from one representative experiment (E; means ± SEM for a total of 10 mice for each genotype).

Activation of NF-κB and MAPKs downstream of Syk is thought to be important for production of proinflammatory cytokines or chemokines including IL-8 (32, 33). Indeed, treatment of HEK293A cells with the NF-κB inhibitors JSH-23 or pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate (PDTC), or with PD98059, an inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK), markedly attenuated the increase in IL-8 production induced by CEACAM20 plus c-Src and Syk (Fig. 6C). In contrast, treatment with SB203580 or SP600125, inhibitors of the MAPKs p38 MAPK and c-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK), respectively, had only a small or no inhibitory effect on such IL-8 production (Fig. 6C). Consistent with these findings, forced expression of CEACAM20(WT) [but not that of CEACAM20(2YF)] together with c-Src and Syk increased the expression of a luciferase reporter gene placed under the transcriptional control of NF-κB response elements (Fig. 6D). These results suggested that activation of NF-κB is important for promotion of IL-8 production by CEACAM20.

Given that we found that tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 and its association with Syk likely promote IL-8 production in cultured cells, we examined whether the expression of KC or MIP-2 occurs in the colonic epithelial cells of Il10−/− or Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice before the apparent onset of colitis. The levels of mRNAs for KC and MIP-2 in colonic epithelial cells isolated from the double-mutant mice at 6–8 wk of age (when the disease activity score was 0–2) were about four and six times, respectively, those in cells isolated from Il10−/− mice (Fig. 6E). In contrast, the amount of mRNA for TNF-α in the cells from Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice was increased only twofold relative to that for Il10−/− mice, whereas the abundance of mRNA for IL-6 did not differ substantially between the two strains (Fig. 6E). These results thus suggested that the expression of MIP-2 and KC tends to be increased in the intestinal epithelium of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice before the development of colitis.

SI Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Reagents.

A rat monoclonal antibody (mAb) to mouse SAP-1 was generated and prepared as described previously (18). Mouse mAbs to β-catenin and to Eps8 were obtained from BD Biosciences, and those to phosphotyrosine (4G10) and to v-Src were from Merck Millipore. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) to Syk (N-19 and C-20), to Fyn (FYN3), and to Muc2 (H-300) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse mAbs to Myc (9E10) and to CEACAM1 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and eBioscience, respectively. Rabbit pAbs to phospho-Syk and to phospho-Src family kinases (p416Src) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology and those to human lysozyme were from Dako. Rabbit pAbs to Frk and a rat mAb to BrdU were from Abcam. Rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin was from Invitrogen. Secondary antibodies labeled with Cy3 or Alexa Fluor 488 for immunofluorescence analysis were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch and Invitrogen, respectively. HRP-conjugated goat secondary antibodies for immunoblot analysis were from Jackson ImmunoResearch. PP2, PP3, JSH-23, PDTC, SB203580, and PD98059 were from Merck Millipore, and SP600125 was from Wako. Mouse mAbs to β-actin and to β-tubulin as well as FITC-labeled 4.4-kDa dextran (FD4) were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Mice.

Sap1−/− mice were generated as described previously (18) and were backcrossed onto the C57BL/6 background for four generations. Il10−/− mice (B6.129P2-Il10tm1Cgn/J) on the C57BL/6 background were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory and crossed with Sap1−/− mice. The resulting Il10+/−Sap1+/− offspring were crossed to generate Il10−/−Sap1−/− and Il10−/− mice for analysis. WT, Sap1−/−, Il10−/−, and Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice were maintained at the Institute of Experimental Animal Research of Kobe University or Gunma University under specific pathogen-free conditions. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Experimentation Committee of Kobe University or Gunma University.

Depletion of Gut Commensal Bacteria.

Gut commensal bacteria in Il10−/− and Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice were depleted as previously described (40). Four-week-old mice were treated with ampicillin (1 g/L; Sigma-Aldrich), neomycin sulfate (1 g/L; Nacalai Tesque), metronidazole (1 g/L; Wako), and vancomycin (500 mg/L; Wako) added to drinking water until analysis.

Generation of Rabbit pAbs to CEACAM20.

A cDNA fragment encoding the cytoplasmic region of mouse CEACAM20 (amino acids 485–577) was amplified by PCR and subcloned into pGEX-4T-1 (GE Healthcare). The encoded GST fusion protein (GST–CC20-cyto) and GST were then prepared as described previously (18). Rabbits were injected with GST–CC20-cyto, and the resulting pAbs to CEACAM20 were purified from serum with the use of columns containing GST or GST–CC20-cyto immobilized on CNBr-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), as described previously (18).

Histological and Immunofluorescence Analyses.

For histological analysis, the colon was removed from mice, washed with ice-cold PBS, and fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 2 h at room temperature. The tissue was then embedded in paraffin and sectioned at a thickness of 3 μm, and the sections were stained with Mayer’s H&E. For immunofluorescence analysis, the colon or ileum was fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS for 2 h at room temperature, transferred to a series of sucrose solutions [7%, 20%, and 30% (wt/vol), sequentially] in PBS, embedded in OCT compound (Sakura), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen sections with a thickness of 5 μm were prepared with a cryostat, mounted on glass slides, and autoclaved in Retrievagen A (pH 6.0) (BD Biosciences) at 110 °C for 10 min for antigen retrieval (41). The sections were then exposed sequentially to primary antibodies and labeled secondary antibodies as described previously (18). Fluorescence images were acquired with a BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus) or an LSM Pascal (Carl Zeiss) or FV1000 (Olympus) confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Electron Microscopy.

Transmission electron microscopy was performed as described previously (18). In brief, mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of sodium pentobarbital (25 mg/kg) and then perfused transcardially with 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Tissues were removed, immersed in the same fixative for 1 h at 4 °C, and then incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with 1% OsO4 in the same buffer. They were then dehydrated and embedded in Epon. For immunoelectron microscopy, tissue samples were fixed by immersion for 2 h at room temperature in PBS containing 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde. Frozen sections with a thickness of 10 μm were then prepared and processed for immunostaining with mAbs to SAP-1 and with Fab fragments of goat pAbs to rat IgG that were labeled with 1.4-nm gold particles (Nanoprobes). Signals were enhanced with the use of an HQ Silver Enhancement Kit (Nanoprobes). The sections were fixed again with 1% OsO4 and 0.1% potassium ferrocyanide and finally embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were prepared, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined with a JEM 1010 electron microscope (JEOL).

Clinical and Histological Assessment of Colitis.

Mice were monitored weekly for stool consistency, stool blood, and anorectal prolapse, and disease activity was scored as described previously (42). Stool consistency was scored as follows: 0 = normal, 2 = loose stools, or 4 = liquid stools. Blood in the stool was scored as: 0 = no blood as revealed with the use of the guaiac occult blood test (Occult Blood Shionogi II; Shionogi), 2 = positive occult blood test, and 4 = gross bleeding. Development of anorectal prolapse was scored as: 0 = no prolapse, 2 = prolapse evident only during defecation, and 4 = prolapse evident at all times. The total score for diarrhea, blood in the stool, and prolapse, ranging from 0 (normal) to 12 (severe), was determined. For scoring of colonic inflammation by histological examination, the entire colon was excised and divided into four segments consisting of proximal, mid, or distal colon and rectum, which were then immediately fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. Paraffin-embedded sections (3 μm) were stained with Mayer’s H&E, and a combined score for inflammatory cell infiltration, tissue damage, and crypt structure was determined in a blinded manner as described previously (42). Inflammatory cell infiltration was scored as follows: 0 = presence of occasional inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, 1 = presence of an increased number of inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, 2 = confluence of inflammatory cells extending into the submucosa, 3 = transmural extension of the infiltrate. Tissue damage was scored as: 0 = no mucosal damage, 1 = lymphoepithelial lesions, 2 = surface mucosal erosion, and 3 = extensive mucosal damage and extension into deeper structures of the colonic wall. Crypt structure was scored as: 0 = normal structure, 1 = occasional hyperplasia without depletion of goblet cells, 2 = hyperplasia with depletion of goblet cells, and 3 = distortion of crypts and the presence of crypt abscesses. Each segment of the colon was given a score based on the three criteria, ranging from 0 (no change) to 9 (severe), and the total score was calculated as the average of the scores from each segment.

Isolation of Mouse IECs.

Mouse IECs were isolated as described previously (43), with minor modifications. In brief, either the ileum or the entire colon was washed with PBS and minced into small pieces, and the minced tissue was washed three times with PBS containing 1 mM DTT and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in HBSS containing 5 mM EDTA and 0.1 mM DTT. The samples were vigorously shaken to detach IECs, which were collected by centrifugation at 800 × g for 5 min after removal of tissue debris.

Isolation of RNA and Quantitative RT-PCR Analysis.

Isolation of total RNA and quantitative RT-PCR analysis were performed as described previously (44), with minor modifications. In brief, total RNA was prepared from freshly isolated whole colon or colonic epithelial cells with the use of Sepasol RNA I (Nacalai Tesque) and an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 0.8 μg of isolated total RNA with the use of a QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen). The cDNA fragments of interest were amplified either with the use of a QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) and ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) or with Fast Start SYBR Green Master (Roche) and a LightCycler 480 (Roche). The amplification was analyzed with the use of either SDS 1.7 software (Applied Biosystems) or LightCycler 480 software (Roche), and the abundance of each target mRNA was normalized by that of Gapdh mRNA. Primer sequences (forward and reverse, respectively) were as follows: IL-1β, 5′-CAACCAACAAGTGATATTCTACATG-3′ and 5′-GATCCACACTCTCCAGCTGCA-3′; IL-4, 5′-GGTCTCAACCCCCAGCTAGT-3′ and 5′-GCCGATGATCTCTCTCAAGTGAT-3′; IL-6, 5′-TAGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC-3′ and 5′-TTGGTCCTTAGCCACTCCTTC-3′; IL-12 p40, 5′-TGGTTTGCCATCGTTTTGCTG-3′ and 5′-ACAGGTGAGGTTCACTGTTTCT-3′; IL-13, 5′-CTCACTGGCTCTGGGCTTCA-3′ and 5′-CTCATTAGAAGGGGCCGTGG-3′; IL-17, 5′-TTTAACTCCCTTGGCGCAAAA-3′ and 5′-CTTTCCCTCCGCATTGACAC-3′; TNF-α, 5′-CCCTCACACTCAGATCATCTTCT-3′ and 5′-GCTACGACGTGGGCTACAG-3′; IFN-γ, 5′-ATGAACGCTACACACTGCATC-3′ and 5′-CCATCCTTTTGCCAGTTCCTC-3′; KC, 5′-CAAGAACATCCAGAGCTTGAAGGT-3′ and 5′-GTGGCTATGACTTCGGTTTGG-3′; MIP-2, 5′-GGGCGGTCAAAAAGTTTGC-3′ and 5′-TGTTCAGTATCTTTTGGATGATTTTCTG-3′; and GAPDH, 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′ and 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′.

BrdU Incorporation Assay.

Whole-body irradiation and a BrdU incorporation assay were performed as described previously (40), with minor modifications. In brief, adult mice were subjected (or not) to x-irradiation (total of 10 Gy). At 3.5 d after irradiation, the animals were injected i.p. with BrdU (50 mg/kg) and killed 2 h later. The ileum or colon was fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde, transferred to a series of sucrose solutions in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, embedded in OCT compound, and rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen. Sections with a thickness of 5 μm were incubated for 30 min at 65 °C with 0.025 M HCl, washed with 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.5), and exposed consecutively to pAbs to BrdU and secondary antibodies labeled with Cy3. Fluorescence images were acquired with a fluorescence microscope or a confocal laser-scanning microscope. BrdU-positive cells in 12 or 40 crypts per animal were counted with the use of ImageJ software (NIH), and the average number per crypt was determined.

In Situ Closed-Loop System.

Paracellular permeability of the colonic epithelium was determined as described previously (45), with minor modifications. In brief, mice were anesthetized and the colon was exposed by an abdominal midline incision. A 2-cm closed loop of the colon was prepared by ligation with a silk suture after washing the lumen of the gut. FD4 (10 mg/kg) in PBS was then injected into the loop, and peripheral blood was collected at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 min thereafter and centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 5 min to obtain the plasma fraction. The fluorescence intensity of FD4 in the plasma samples was measured with the use of a fluorescence spectrophotometer (MTP-600F; Corona Electric).

Preparation of Microvillus Membranes.

Microvillus membranes were prepared from intestinal mucosal scrapings of adult mice as described previously (46). In brief, the entire small intestine was removed, flushed, and opened longitudinally. The mucosal villi were then scraped off with glass slides and homogenized with a Polytron disrupter (PT-2100; Kinematica AG) for 3 min at 4 °C in a solution containing 50 mM mannitol, 2 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.1), a protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich), and soybean trypsin inhibitor (50 μg/mL). After the addition of 1 M CaCl2 to a concentration of 10 mM, the homogenate was incubated for 20 min at 4 °C and then centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was then centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the pellet was collected as the microvillus membrane fraction for analysis.

Affinity Purification of Tyrosine-Phosphorylated Proteins from Microvillus Membranes.

Microvillus membranes prepared as described above were solubilized in SDS buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS] and then diluted 10 times with TNE buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100] containing 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin (10 μg/mL), and 1 mM sodium vanadate before centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was applied to a column that contained mAbs to phosphotyrosine (4G10) conjugated to agarose beads (Merck Millipore) and which had been equilibrated with TNE buffer. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins were eluted from the column with TNE buffer containing 0.1 M disodium phenyl phosphate, precipitated with 10% (wt/vol) TCA, and then subjected to SDS/PAGE followed by silver staining.

Mass Spectrometry.

Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins of microvillus membranes were identified by mass spectrometry (MS) as previously described (41). In brief, proteins visualized by silver staining after SDS/PAGE were excised from the gel and subjected to in-gel digestion overnight at 37 °C with trypsin (Promega) in a solution containing 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.0) and 2% (vol/vol) acetonitrile. The tryptic peptides were subjected to MALDI-TOF MS with an Ultraflex TOF/TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics). Proteins were identified by comparison of the peptide molecular masses determined by MALDI-TOF MS with theoretical peptide masses for proteins registered in NCBInr.

Expression Vectors.

Expression vectors for mouse SAP-1(WT), the catalytically inactive mutant SAP-1(C/S), the substrate-trapping mutant SAP-1(D/A), and the cytoplasmic deletion mutant SAP-1(ΔCP) were described previously (43). An expression vector for mouse CEACAM1 was kindly provided by N. Beauchemin (McGill University, Montreal). For construction of an expression vector for mouse CEACAM20(WT), a full-length cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR from total RNA of mouse (C57BL/6) intestine with the primers 5′-GAACTCATGGAGCTTGCTTCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCAGGCTGATGGGGTGATCTT-3′ (reverse) and then subcloned into pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). Expression vectors for CEACAM20 with an NH2- or COOH-terminal Myc-epitope tag (MycCC20 or CC20Myc, respectively) were constructed by PCR-ligation–PCR mutagenesis as described previously (47). An expression vector for the mutant CEACAM20(2YF), in which Tyr559 and Tyr570 are replaced with Phe, was also generated by PCR-ligation–PCR mutagenesis. For generation of an expression vector for a Myc-epitope–tagged mutant of CEACAM20 [CEACAM20(ΔCP)] lacking the cytoplasmic region (amino acids 1–461), the mutated cDNA was amplified by PCR with MycCC20 cDNA as a template and then subcloned into pcDNA3.1. An expression vector for porcine Syk was kindly provided by K. Sada (Fukui University, Fukui, Japan), and those for c-Src or an active mutant of Fyn (Fyn CA) were prepared as described (43). A full-length cDNA for mouse Frk was obtained from DNAFORM and subcloned into pcDNA3.1. For construction of expression vectors for GST fusion proteins containing the cytoplasmic region of mouse SAP-1 (amino acids 648–971) or the region of mouse Syk containing the two SH2 domains (amino acids 1–265), the corresponding cDNA fragments were amplified by PCR and subcloned into pGEX-5X-1 (GE Healthcare). The sequences of all PCR products were verified by sequencing with the use of an ABI3100 instrument (Applied Biosystems).

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HEK293A cells (Invitrogen) were cultured in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine. The cells were transfected with expression vectors with the use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblot Analysis.

Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then lysed on ice either in TNE buffer containing 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin (10 μg/mL), and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, or in ODG buffer [20 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5% (wt/vol) glycerol, 2% (wt/vol) n-octyl-β-d-glucoside] containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Nacalai Tesque) and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The lysates were centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis as previously described (18, 43). For preparation of lysates from mouse tissues, tissues were homogenized with a Teflon homogenizer on ice in TNE buffer containing 1 mM PMSF, aprotinin (10 μg/mL), and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The homogenates were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with rotation and were then centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants were subjected to immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

In Vitro Dephosphorylation Assay.

GST and GST fusion proteins containing the cytoplasmic domain of either SAP-1(WT) or SAP-1(C/S) were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified with the use of glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) as previously described (43). CC20Myc-expressing HEK293A cells were treated with 100 μM sodium pervanadate for 5 min and then lysed in TNE buffer, and the lysates were centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants (20 μg) were subjected to immunoprecipitation with antibodies to Myc, and the resulting precipitates were incubated for 20 min at 30 °C with 0.5 μg of GST or the GST–SAP-1(WT) or GST–SAP-1(C/S) fusion proteins in phosphatase assay buffer [20 mM Mes (pH 6.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA] before immunoblot analysis with mAbs to phosphotyrosine or to Myc.

Pull-Down Assay.

GST and a GST fusion protein containing the SH2 domains of Syk were expressed in E. coli and purified as described above. Pervanadate-treated cells were lysed in TNE buffer and centrifuged at 17,400 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The resulting supernatants (20 μg) were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C with either GST (1 μg) or GST–Syk-SH2 (1 μg) immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads in TNE buffer. The beads were washed extensively with TNE buffer, and the bound proteins were then subjected to immunoblot analysis.

Assay for IL-6 and IL-8 Production.

Transfected HEK293A cells were cultured for 24 h in fresh culture medium with or without JSH-23 (10 μM), PDTC (100 μM), SB203580 (10 μM), SP600125 (10 μM), or PD98059 (100 μM). The concentration of IL-6 or IL-8 in culture supernatants was then determined with the use of an ELISA kit (R&D Systems).

Reporter Assay.

HEK293A cells were transfected for 24 h with expression vectors for CEACAM20, c-Src, or Syk together with the NF-κB reporter plasmid pGL4.32 (Promega) and the internal control plasmid pRL-TK (Promega). The cells were then lysed and assayed for luciferase activity with the use of a dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and a luminometer (TD-20/20; Turner Designs). The activity of firefly luciferase was normalized by that of Renilla luciferase.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SEM and were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney u test or Student’s t test for comparisons between two groups or by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for comparisons among three or more groups. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with the use of GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software).

Discussion

We have here shown that ablation of SAP-1, a microvillus-specific PTP, exacerbated spontaneous colitis in association with up-regulation of mRNAs for various cytokines and chemokines in the colon of Il10−/− mice, whereas Sap1−/− mice did not manifest any sign of colonic inflammation. IL-10 is thought to suppress the functions of various immune cells in the intestine, thereby protecting against colitis (34). Ablation of IL-10 in mice thus results in colonic inflammation that resembles IBD in humans (21, 22). Depletion of commensal bacteria with antibiotics also attenuates the severity of colitis in Il10−/− mice (21, 24), suggesting the importance of such bacteria in this colitis model. We found that antibiotic treatment also prevented the exacerbation of colitis induced by SAP-1 ablation in Il10−/− mice. Our results thus suggest that SAP-1, in cooperation with IL-10, contributes to protection against the development of colitis.

We also investigated the molecular mechanism by which SAP-1 regulates intestinal immunity and by which ablation of SAP-1 exacerbates colitis in Il10−/− mice. We found that the extent of tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20, which is specifically expressed in IECs, was markedly increased in Sap1−/− mice. We also showed that tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 was efficiently dephosphorylated by SAP-1 in vitro as well as in cultured cells. Moreover, the expression pattern and localization of CEACAM20 overlapped with those of SAP-1, with both proteins being localized at microvilli of the intestine. Furthermore, SAP-1 and CEACAM20 were found to form a complex through interaction of their ectodomains in cultured cells, suggesting that both proteins physically associate with each other. Collectively, these observations suggest that CEACAM20 is a physiological substrate for SAP-1 in the intestinal epithelium.

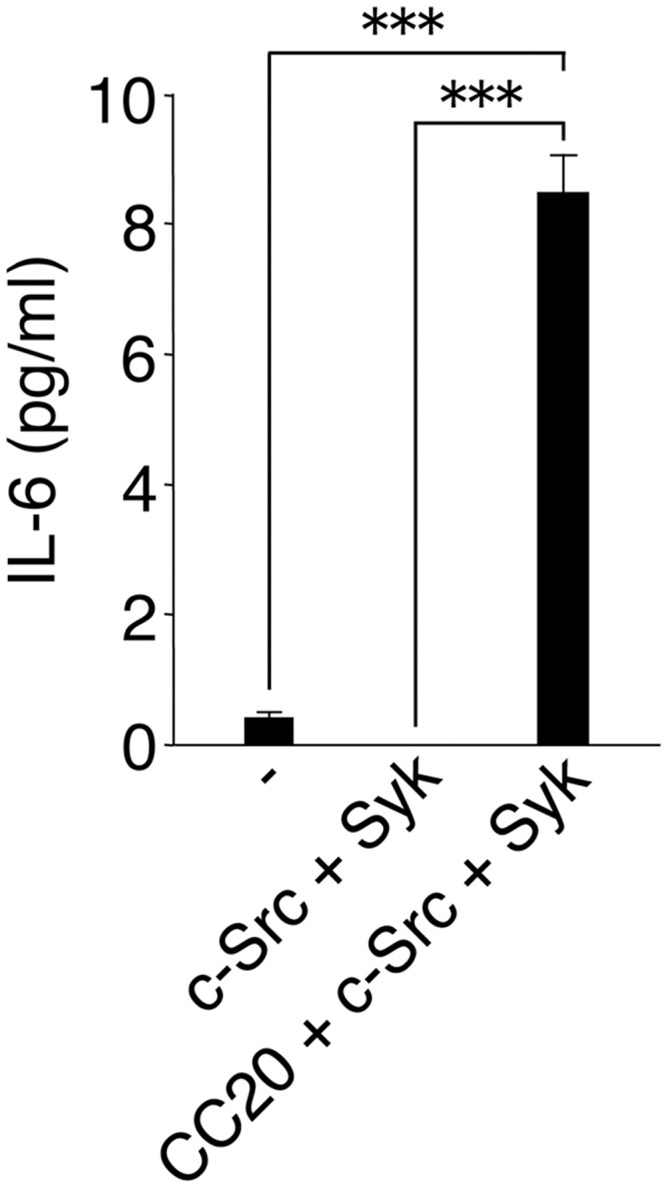

Given that we found that SAP-1 regulates intestinal immunity through dephosphorylation of CEACAM20, we also investigated the function as well as signaling downstream of CEACAM20. We found that c-Src promotes the phosphorylation of Tyr559 or Tyr570 in the COOH-terminal region of CEACAM20 and that Syk then binds to tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 through its SH2 domains. Such binding to CEACAM20 likely results in the activation of Syk and promotes further tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20. Finally, we showed that formation of the CEACAM20–Syk complex promoted the production of IL-8, likely as a result of the activation of NF-κB, in cultured cells. In contrast, forced expression of SAP-1 markedly attenuated the increase in IL-8 production induced by expression of CEACAM20 and c-Src, suggesting that SAP-1 counteracts the effect of tyrosine phosphorylation of CEACAM20 on IL-8 production. We have also found that forced expression of CEACAM20 together with c-Src and Syk induces the production of IL-6 in HEK293A cells (Fig. S9). CEACAM20 thus likely promotes inflammatory conditions in the intestine through its formation of a complex with Syk and the consequent production of chemokines and cytokines in IECs.

Fig. S9.

Forced expression of CEACAM20 together with c-Src and Syk promotes IL-6 production in cultured cells. HEK293A cells transfected with expression vectors for the indicated proteins were cultured for 24 h. The concentration of IL-6 in the culture supernatants was then determined. Data are means ± SEM of triplicates for each condition and are representative of three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001 (ANOVA and Tukey’s test).

Neutrophil infiltration into the intestinal mucosa is fundamental to the development and progression of IBD (35). The chemokine IL-8 is thought to play a major role in the neutrophil infiltration that is frequently associated with colitis lesions in individuals with IBD (35). Mice deficient in chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 2 (CXCR2), a receptor for the IL-8 homologs MIP-2 and KC, manifest a reduced susceptibility to dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis, another animal model of IBD (36). Conversely, transgenic mice that overexpress MIP-2 specifically in the intestinal epithelium manifest exaggeration of such colitis (14). The levels of mRNAs for MIP-2 and KC tended to increase in the intestinal epithelium of Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice before the development of colitis. The tyrosine-phosphorylation of CEACAM20 thus likely contributes at least in part to the development of colitis in Il10−/−Sap1−/− mice.

We found that the ectodomain of SAP-1 interacts with that of CEACAM20. Given that both proteins are localized at microvilli of IECs, they—and in particular CEACAM20—might also interact with commensal bacteria in the intestine. Indeed, the Ig-like ectodomain of another CEACAM family member, CEACAM3, which also contains an ITAM-like motif in its cytoplasmic domain, recognizes bacteria that express the Opa protein and thereby triggers phagocytosis and elimination of the bacteria by granulocytes (37). In addition, CEACAM5 and CEACAM6, which are expressed in human IECs, have been shown to function as a receptor for Escherichia coli isolated from the intestine of healthy individuals or IBD patients (38, 39). Similarly, commensal or pathogenic bacteria might contribute to the regulation of CEACAM20 function by interacting with the ectodomain of this protein at the microvilli of IECs.

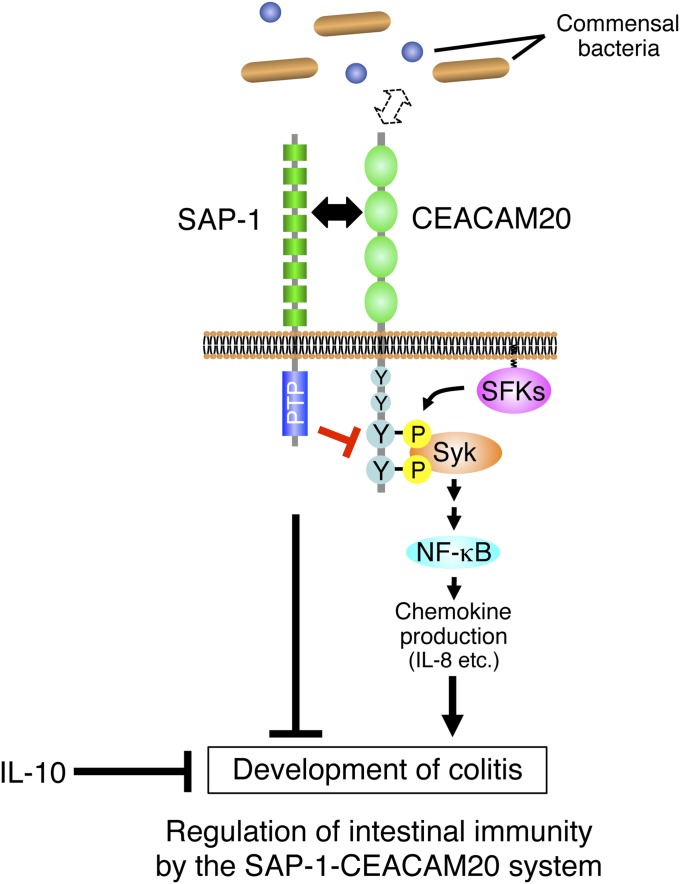

In summary, we propose a model for regulation of intestinal immunity by SAP-1 and CEACAM20 (Fig. 7). Further study will be required to elucidate whether mutations of the genes for SAP-1 or CEACAM20 are associated with IBD in humans. Nevertheless, these molecules are potential drug targets for the treatment of IBD.

Fig. 7.

Model for regulation of intestinal immunity by the SAP-1–CEACAM20 system. SAP-1 is a microvillus-specific PTP that together with IL-10 protects against the development of colitis. SAP-1 negatively regulates the function of CEACAM20 by mediating its dephosphorylation. CEACAM20 is also a microvillus-specific protein whose ectodomain likely interacts with that of SAP-1. It also possesses in its cytoplasmic region an ITAM, which is phosphorylated by SFKs and serves as a binding site for the SH2 domains of the tyrosine kinase Syk. The formation of a complex by tyrosine-phosphorylated CEACAM20 and Syk induces the activation of NF-κB and thereby increases the production of chemokines such as IL-8 and promotes inflammation of the intestinal mucosa.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies, reagents, mice, expression vectors, and detailed methods for gut commensal bacteria depletion, antibody generation, histological and immunofluorescence analyses, electron microscopy, clinical and histological assessment of colitis, mouse IEC isolation, RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR analysis, BrdU incorporation assay, in situ closed-loop system, microvillus membrane preparation, affinity purification and MS, cell culture and transfection, immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis, in vitro dephosphorylation assay, IL-6 and IL-8 production assay, reporter assay, and statistical analysis used in this study can be found in SI Materials and Methods. This study was approved by the Animal Care and Experimentation Committees of Kobe University and Gunma University.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Harada for the generation of Sap1−/− mice; N. Beauchemin and K. Sada for expression vectors; as well as K. Tomizawa, H. Kobayashi, Y. Hayashi, Y. Niwayama-Kusakari, M. Inagaki, and E. Urano for technical assistance. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas Cancer, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) and (C), a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B), and a grant of the Global Center of Excellence Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. This work was also performed with support from the Cooperative Research Project Program of the Medical Institute of Bioregulation (Kyushu University).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1510167112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Peterson LW, Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: Regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross MH, Pawlina W. Histology. A Text and Atlas With Correlated Cell and Molecular Biology. Ed 5. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 2006. pp. 102–121, 518–175. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laukoetter MG, et al. JAM-A regulates permeability and inflammation in the intestine in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204(13):3067–3076. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermiston ML, Gordon JI. Inflammatory bowel disease and adenomas in mice expressing a dominant negative N-cadherin. Science. 1995;270(5239):1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448(7152):427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouellette AJ. Paneth cell α-defensins: Peptide mediators of innate immunity in the small intestine. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2005;27(2):133–146. doi: 10.1007/s00281-005-0202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostaff MJ, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Antimicrobial peptides and gut microbiota in homeostasis and pathology. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(10):1465–1483. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramasundara M, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, Day AS. Defensins and inflammation: The role of defensins in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi KS, et al. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307(5710):731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaser A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134(5):743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Sluis M, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(1):117–129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heazlewood CK, et al. Aberrant mucin assembly in mice causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and spontaneous inflammation resembling ulcerative colitis. PLoS Med. 2008;5(3):e54. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung HC, et al. A distinct array of proinflammatory cytokines is expressed in human colon epithelial cells in response to bacterial invasion. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(1):55–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI117676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohtsuka Y, Sanderson IR. Dextran sulfate sodium-induced inflammation is enhanced by intestinal epithelial cell chemokine expression in mice. Pediatr Res. 2003;53(1):143–147. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200301000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Günther C, et al. Caspase-8 regulates TNF-α-induced epithelial necroptosis and terminal ileitis. Nature. 2011;477(7364):335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature10400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welz PS, et al. FADD prevents RIP3-mediated epithelial cell necrosis and chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2011;477(7364):330–334. doi: 10.1038/nature10273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matozaki T, et al. Expression, localization, and biological function of the R3 subtype of receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatases in mammals. Cell Signal. 2010;22(12):1811–1817. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadakata H, et al. SAP-1 is a microvillus-specific protein tyrosine phosphatase that modulates intestinal tumorigenesis. Genes Cells. 2009;14(3):295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2008.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noguchi T, et al. Inhibition of cell growth and spreading by stomach cancer-associated protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1 (SAP-1) through dephosphorylation of p130cas. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(18):15216–15224. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takada T, et al. Induction of apoptosis by stomach cancer-associated protein-tyrosine phosphatase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(37):34359–34366. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206541200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kühn R, Löhler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75(2):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berg DJ, et al. Enterocolitis and colon cancer in interleukin-10-deficient mice are associated with aberrant cytokine production and CD4+ TH1-like responses. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(4):1010–1020. doi: 10.1172/JCI118861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwakura Y, Ishigame H. The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1218–1222. doi: 10.1172/JCI28508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sellon RK, et al. Resident enteric bacteria are necessary for development of spontaneous colitis and immune system activation in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66(11):5224–5231. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5224-5231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zebhauser R, et al. Identification of a novel group of evolutionarily conserved members within the rapidly diverging murine Cea family. Genomics. 2005;86(5):566–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roskoski R., Jr Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure and regulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;324(4):1155–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tocchetti A, Confalonieri S, Scita G, Di Fiore PP, Betsholtz C. In silico analysis of the EPS8 gene family: Genomic organization, expression profile, and protein structure. Genomics. 2003;81(2):234–244. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zalzali H, et al. CEACAM1, a SOX9 direct transcriptional target identified in the colon epithelium. Oncogene. 2008;27(56):7131–7138. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Songyang Z, et al. SH2 domains recognize specific phosphopeptide sequences. Cell. 1993;72(5):767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90404-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Songyang Z, et al. Specific motifs recognized by the SH2 domains of Csk, 3BP2, fps/fes, GRB-2, HCP, SHC, Syk, and Vav. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14(4):2777–2785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thuveson M, Albrecht D, Zürcher G, Andres AC, Ziemiecki A. iyk, a novel intracellular protein tyrosine kinase differentially expressed in the mouse mammary gland and intestine. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;209(2):582–589. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mócsai A, Ruland J, Tybulewicz VL. The SYK tyrosine kinase: A crucial player in diverse biological functions. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(6):387–402. doi: 10.1038/nri2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau C, et al. Syk associates with clathrin and mediates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation during human rhinovirus internalization. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):870–880. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kole A, Maloy KJ. Control of intestinal inflammation by interleukin-10. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;380:19–38. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-43492-5_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keshavarzian A, et al. Increased interleukin-8 (IL-8) in rectal dialysate from patients with ulcerative colitis: Evidence for a biological role for IL-8 in inflammation of the colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(3):704–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buanne P, et al. Crucial pathophysiological role of CXCR2 in experimental ulcerative colitis in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82(5):1239–1246. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buntru A, Roth A, Nyffenegger-Jann NJ, Hauck CR. HemITAM signaling by CEACAM3, a human granulocyte receptor recognizing bacterial pathogens. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;524(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tchoupa AK, Schuhmacher T, Hauck CR. Signaling by epithelial members of the CEACAM family: Mucosal docking sites for pathogenic bacteria. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-12-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray-Owen SD, Blumberg RS. CEACAM1: Contact-dependent control of immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6(6):433–446. doi: 10.1038/nri1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118(2):229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohnishi H, et al. Stress-evoked tyrosine phosphorylation of signal regulatory protein α regulates behavioral immobility in the forced swim test. J Neurosci. 2010;30(31):10472–10483. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0257-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanazawa Y, et al. Role of SIRPα in regulation of mucosal immunity in the intestine. Genes Cells. 2010;15(12):1189–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murata Y, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of R3 subtype receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatases and their complex formations with Grb2 or Fyn. Genes Cells. 2010;15(5):513–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato-Hashimoto M, et al. Signal regulatory protein α regulates the homeostasis of T lymphocytes in the spleen. J Immunol. 2011;187(1):291–297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao Y, et al. Improvement of intestinal absorption of water-soluble macromolecules by various polyamines: Intestinal mucosal toxicity and absorption-enhancing mechanism of spermine. Int J Pharm. 2008;354(1-2):126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thompson JF, Buikhuisen WA. Protein tyrosine kinase activity and its substrates in rat intestinal microvillus membranes. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(2):370–379. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mori M, et al. Promotion of cell spreading and migration by vascular endothelial-protein tyrosine phosphatase (VE-PTP) in cooperation with integrins. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224(1):195–204. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]