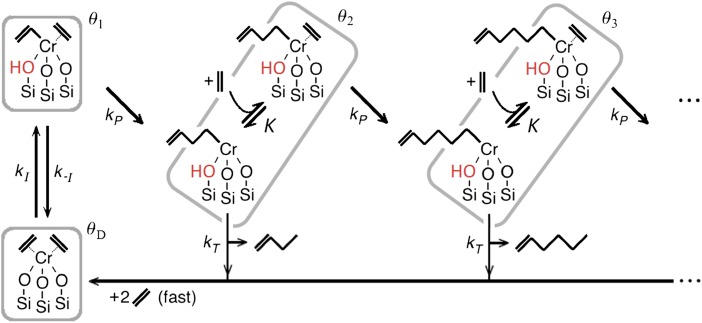

Delley et al. (1) propose a new proton transfer mechanism to explain the mysterious initiation mechanism (2) of the Phillips polymerization catalyst. The authors’ mechanism invokes dormant (D) sites and active Si(OH)CrR sites, as summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Initiation (I), propagation (P), and termination (T) steps in the mechanism of Delley et al. (1). The authors report standard free-energy changes and barriers for all steps except for the ethylene binding constant K, which lies in the range 0.1/atm < K < 10/atm, based on quantities from their paper and Supporting Information.

A combination of transition state theory, Delley et al.’s (1) density functional theory (DFT) results, and standard microkinetic modeling techniques (3) for the mechanism of Fig. 1 yield several testable predictions. DFT is not sufficiently accurate to predict absolute rates, but selectivities, molecular weights, and relative abundances can often be predicted more accurately because they involve ratios of rates. Relative abundances are particularly important because the evidence for proton transfer hinges upon the assignment of infrared (IR) peaks at 3,640 and 3,605 cm−1 to Si(OH)Cr–R intermediates (1). According to the proposed mechanism, the total abundance of these species is

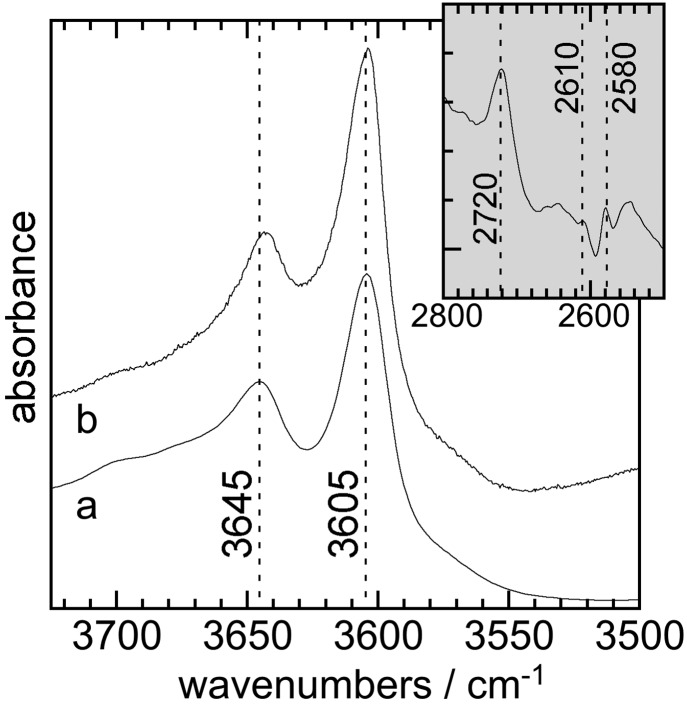

Because the proton transfer step is unfavorable and slow, the authors’ computed free energies predict , meaning the Si(OH)Cr–R sites would be extremely rare and therefore unobservable (1). To ascribe the predicted vanishingly small abundance to DFT error (typically approximately ±5–10 kcal/mol for B3LYP) would invoke uncharacteristically large errors, approximately 17 kcal/mol = kBT ln[109] at temperatures of catalyst operation (4). When ab initio calculations for a hypothesized mechanism result in such large discrepancies, it is useful to consider alternative mechanisms and interpretations of data. When polyethylene samples are sufficiently thick, the polymer itself shows bands at 3,605 and 3,640 cm−1 (5), which are likely two-phonon combinations of CH2 asymmetric stretching (2,883/2,919 cm−1) and rocking modes (721/731 cm−1) (5). We and others have observed these peaks after removal of Phillips catalyst and in polyethylene made with different catalysts (Fig. 2), as well as in paraffins of noncatalytic origin.

Fig. 2.

Transmission IR spectra of polyethylene thin films: (a) made by a supported catalyst Cr[CH(SiMe3)2]3/SiO2, after extraction of the catalyst with HF; and (b) made by a homogeneous catalyst, [(C6H3Me2)N = C(Me)C(NC6H3Me2)O-κ2-N,O]Ni(η1-CH2CMeCH2)(PMe3), activated by B(C6F5)3. The Inset shows the spectrum of deuterium-labeled polyethylene.

Another major issue involves the proposed termination mechanism. The proton transfer termination pathway is effectively the microscopic reverse of the initiation pathway (apart from vinyl vs. alkyl chain differences and steric effects of the polymer). Although the authors included a π-bound ethylene ligand to facilitate initiation, they omitted π-bound ethylene in the termination steps (1). Furthermore, the authors dismiss termination by β-H transfer, citing a large barrier to product diene release (see figure S8 in ref. 1). However, ethylene may assist in diene displacement after β-H termination. This alternative termination pathway is important because it would regenerate an Si(OH)CrH site that is ready to insert ethylene, and thus create a faster polymerization cycle. However, the dormant (D) state would still act as an off-cycle trap for vast majority of Cr sites.

In summary, Delley et al.’s (1) calculations do not support their interpretation of the new IR peaks as evidence for the Si(OH)Cr–R site. Moreover, the IR peaks are indistinguishable from peaks that are intrinsic to polyethylene. Further studies of alternative pathways and site geometries are needed to determine whether Si(OH)Cr–R sites can catalyze ethylene polymerization.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Department of Energy Basic Energy Sciences for support under Grant DE-FG02-03ER15467.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Delley MF, et al. Proton transfers are key elementary steps in ethylene polymerization on isolated chromium(III) silicates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11624–11629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405314111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDaniel M. A review of the Phillips supported chromium catalyst and its commercial use for ethylene polymerization. In: Gates BC, Knozinger H, editors. Advances in Catalysis. Vol 53. Academic; New York: 2010. pp. 123–606. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keii T. Heterogeneous Kinetics: Theory of Ziegler-Natta-Kaminsky Polymerization. Springer; Berlin: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey J. On the accuracy of density functional theory in transition metal chemistry. Ann Rep Prog Chem C. 2006;102:203–226. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen J, Woollett A. Vibrational spectra of polyethylenes and related substances. J Chem Phys. 1957;26(6):1391–1400. [Google Scholar]