Significance

Cortical neurons exhibit spontaneous activity without explicit external stimuli. Sensory stimuli not only activate specific populations of those neurons but can also silence other populations. However, it remains unclear whether neuronal silencing per se leads to memory formation and behavioral expression. Here, we used optogenetic silencing of a neuronal ensemble in the auditory cortex and found that mice exhibited a fear response to silencing that had been previously paired with footshock, and could find a reward based on the presence or absence of the silencing. These findings indicate that neuronal silencing per se, which is originally believed to be involved in neuronal modulation, is enough to elicit a cognitive behavior.

Keywords: fear conditioning, operant conditioning, optogenetics, neuronal inhibition, auditory cortex

Abstract

Sensory stimuli not only activate specific populations of cortical neurons but can also silence other populations. However, it remains unclear whether neuronal silencing per se leads to memory formation and behavioral expression. Here we show that mice can report optogenetic inactivation of auditory neuron ensembles by exhibiting fear responses or seeking a reward. Mice receiving pairings of footshock and silencing of a neuronal ensemble exhibited a fear response selectively to the subsequent silencing of the same ensemble. The valence of the neuronal silencing was preserved for at least 30 d and was susceptible to extinction training. When we silenced an ensemble in one side of auditory cortex for conditioning, silencing of an ensemble in another side induced no fear response. We also found that mice can find a reward based on the presence or absence of the silencing. Neuronal silencing was stored as working memory. Taken together, we propose that neuronal silencing without explicit activation in the cerebral cortex is enough to elicit a cognitive behavior.

Cortical neurons exhibit spontaneous activity without explicit external stimuli (1–3), which may not only increase, but also be suppressed, by sensory stimuli (4, 5). For example, auditory stimuli suppress a subset of auditory cortical neurons in a frequency-dependent manner (5). Synaptic inhibition in the cerebral cortex is fundamental for neuronal modulation (6), including gain control (7), response selectivity (8, 9), and synchronized activities (10, 11). Inhibition-based modulations may contribute to stimulus-driven behaviors and associative memories of sensory stimuli (12); however, it remains unclear whether neuronal silencing (i.e., a transient reduction in firing rates from their spontaneous level) by itself can serve as a memory trace and bring about behavioral expressions. In this study, we tested this possibility by optogenetically silencing auditory cortical neurons.

Results

Archaerhodopsin Expression in the Auditory Cortex.

To silence excitatory neurons in the auditory cortex, we injected an adeno-associated virus vector expressing archaerhodopsin (Arch) (13) under the control of the calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) promoter (AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP) into the auditory cortex of mice (Fig. 1A). Three weeks after virus injection, we observed robust expression of Arch-EYFP in the auditory cortex (Fig. 1B). We obtained whole-cell recordings from Arch-expressing neurons in auditory cortical slices and confirmed that green-light illumination induced an outward current and inhibited action potentials induced by depolarizing current injections (Fig. 1 C and D). To confirm the inhibitory effect in vivo, we recorded multiunit activities from the auditory cortex of the anesthetized mice. The overall firing rate was reduced by 29.2 ± 7.7% during green-light illumination (eight tetrodes from two mice) (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Green light illumination inhibits the activity of Arch-expressing auditory cortical neurons. (A) Mice were injected with AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP and implanted with optical fibers in the auditory cortex (Au). (B) Arch-EYFP expression in the auditory cortex. (C and D) Green light illumination induced an outward current (C) and silenced action potentials (D) in Arch-expressing neurons. (E) Green light illumination decreased multiunit activities in the auditory cortex of anesthetized mice. (Upper) Representative raster plots of one channel. (Lower) Average normalized multiunit activities. Paired t test with Bonferroni correction, Pre vs. Light ON, t7 = 3.8, *P = 0.0069. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Neuronal Silencing Induces Conditioned Fear Response.

We asked whether temporal silencing of auditory cortical neurons can be a conditioned stimulus (CS) in a fear conditioning. If this is the case, mice receiving pairings of footshock with the silencing should exhibit fear responses to the subsequent silencing alone. Three weeks after injection of AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP and implantation of optical fibers into the auditory cortex, mice underwent 16 pairings of footshock with green light delivery to the auditory cortex (Fig. 2A). On the next day, they (the Arch/paired group) showed robust freezing during light ON epochs (Fig. 2 B and C). The latency from the light delivery to freezing was about 1 s (Fig. S1). The mice receiving AAV-CaMKII-EYFP (control), instead of CaMKII-Arch, showed little freezing during either light ON or OFF epochs. To test whether neuronal silencing by itself leads to freezing behavior, we prepared Arch/unpaired group. Mice of this group received AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP and underwent an unpaired conditioning consisted of 16 temporally unpaired presentations of light delivery and footshock. In the test, Arch/unpaired group showed little freezing during either light ON or OFF epochs. These results indicate that the silencing of auditory cortical neurons can be a cue of memory formation and retrieval in a fear conditioning paradigm.

Fig. 2.

Mice learn an association between footshock and optogenetic silencing of auditory cortical neurons. (A) Mice received 16 pairings of footshock with green light delivery to the auditory cortex. (B) The Arch/paired group (n = 10) showed freezing behavior in response to the light delivery (Arch/unpaired group, n = 7; EYFP/paired group, n = 7). (C) Averaged freezing time during five light ON epochs. One-way ANOVA, F2,21 = 16.9, P = 4.2 × 10−5. Tukey’s test, Arch paired vs. EYFP paired, ***P = 2.3 × 10−4; Arch paired vs. Arch unpaired, ***P = 2.2 × 10−4. (D) Light delivery induced a conditioned fear response even 30 d after conditioning, which was extinguished by repeated light delivery (n = 8). Repeated measures ANOVA, F30,210 = 17.1, P = 2.0 × 10−41.

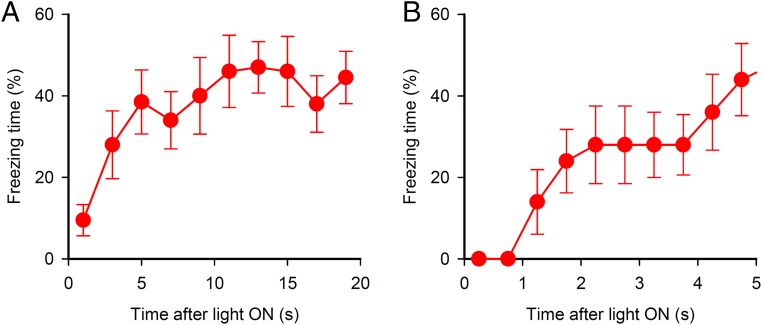

Fig. S1.

Freezing time of Arch/paired mice over light ON period. Freezing time during five CS periods was averaged. (A) Freezing time during the whole CS period. (B) Freezing time during 5 s from the start of CS. Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

The Valence of the Neuronal Silencing Is Preserved for a Long Time and is Susceptible to Extinction Training.

We next tested whether the association between neuronal silencing and shock is preserved over the long term. We prepared different mice receiving AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP, subjected them to paired conditioning, and tested freezing behavior responsive to the light delivery 1 and 30 d after conditioning. They exhibited freezing response during light ON epochs even 30 d after conditioning (Fig. 2D). This result indicates that an associative memory between neuronal silencing and shock lasts for at least 30 d.

One of characteristics of a conditioned stimulus is that a subsequent behavioral response to the stimulus is susceptible to conditions in which the prior stimulus was given. For example, a conditioned fear response to a tone, light or context that are paired with shock is extinguished by repeated presentation of the stimulus that is not accompanied with shock. Therefore, we tested whether the association between neuronal silencing and shock undergoes extinction. We subjected the mice that underwent 30-d test to an extinction training, where the mice received 20-s light delivery without shock 30 times a day over 4 d. The conditioned fear response to silencing was gradually attenuated, and mice showed little freezing in the fourth day of the extinction training (Fig. 2D).

Silencing of a Small Subset of Neurons Is Sufficient to Produce and Retrieve Fear Memory.

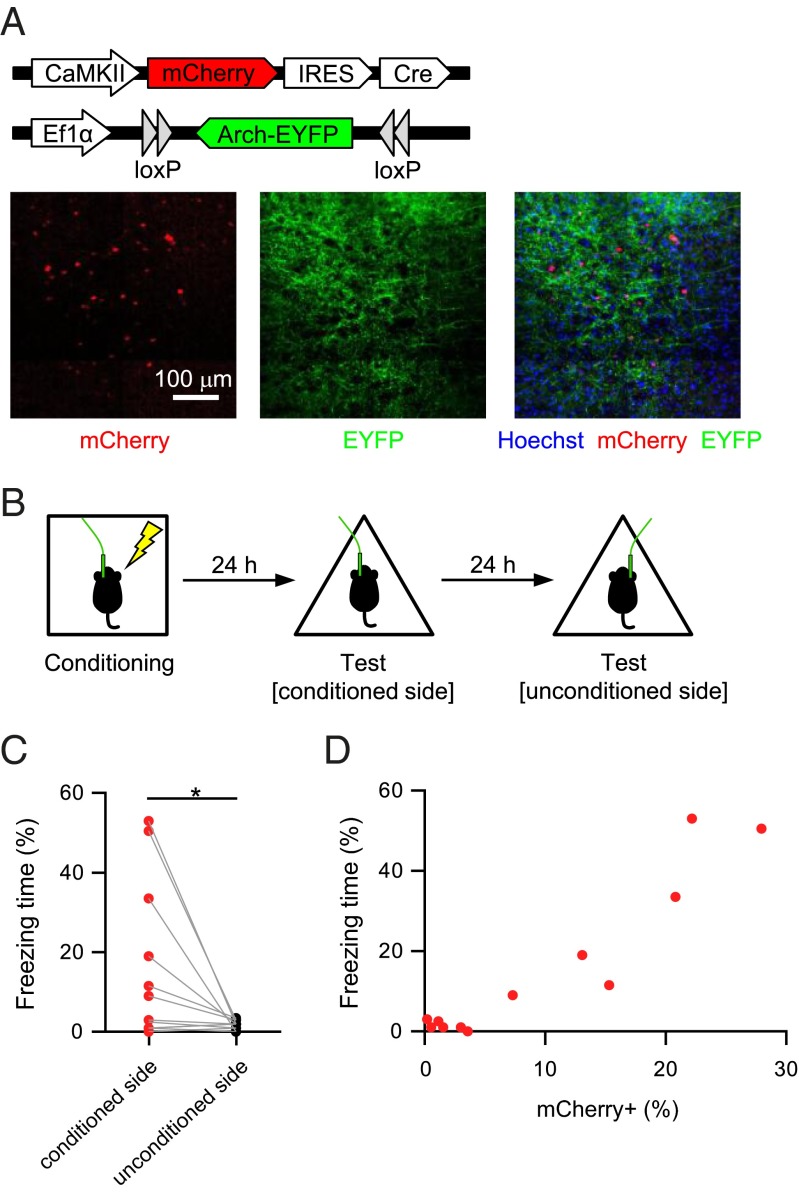

In the experiments above, a great number of auditory cortical neurons expressed Arch (Fig. 1B). Can silencing of a smaller number of neurons act as a conditioned stimulus? To test this possibility, we achieved a high level of Arch expression in a smaller number of neurons by coinjecting a low titer of AAV-CaMKII-mCherry-Cre and a high titer of the AAV vector encoding Cre-dependent Arch (AAV-Ef1α-DIO-Arch-EYFP) (Fig. 3A). Mice underwent 16 pairings of footshock with light delivery to one side of the auditory cortex (Fig. 3B). They showed freezing behavior in response to light delivery to the conditioned side, but not the unconditioned side (Fig. 3C). We examined the relationship between the freezing time in response to the light delivery to the conditioned side and the proportion of mCherry+ neurons (putative Arch+ neurons) in the targeted region (Fig. 3D and Table S1). Mice in which more than 5% of the neurons were labeled with mCherry exhibited freezing response to the light delivery (freezing time, 29.42 ± 7.88%; n = 6 mice), whereas mice in which fewer than 5% of the neurons were labeled with mCherry showed little freezing behavior (1.42 ± 0.45%, n = 6 mice).

Fig. 3.

Silencing of a small subset of neurons is sufficient to produce and retrieve fear memory. (A) Arch-EYFP expression in a small number of auditory cortical neurons. (B) Behavioral procedure for C and D. (C) Mice showed freezing behavior in response to light delivery to the conditioned, but not the unconditioned side. Each plot denotes the averaged value during light ON epochs (n = 12, *P = 0.033, t11 = 2.4, paired t test). (D) Relationship between the freezing time in response to light delivery on the conditioned side and the proportion of mCherry+ neurons in that area.

Table S1.

Number of transfected cells in the experiment for silencing of a small subset of neurons

| Freezing time, % | No. of mCherry+ cells | Total no. of cells |

| 0.0 | 20 | 554 |

| 1.0 | 6 | 386 |

| 1.0 | 13 | 432 |

| 1.0 | 22 | 456 |

| 2.5 | 6 | 516 |

| 3.0 | 1 | 468 |

| 9.0 | 37 | 499 |

| 11.5 | 58 | 391 |

| 19.0 | 71 | 528 |

| 33.5 | 87 | 422 |

| 50.5 | 114 | 410 |

| 53.0 | 107 | 483 |

Cells were counted in a 500 μm × 500 μm area below the estimated position of the optical fiber tip from two 40-μm-thick slices per mouse.

Mice Can Find Rewards Based on Neuronal Silencing.

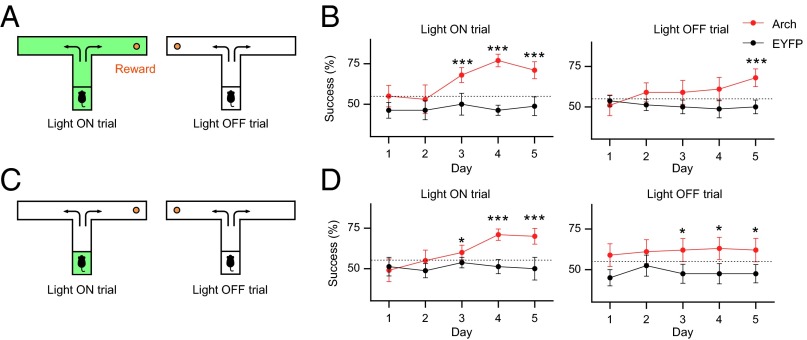

Operant conditioning is another type of learning task, in which individuals learn an association between a particular behavior and a consequence. We examined whether mice can use the information of neuronal silencing to find a reward in an operant conditioning paradigm. We placed a sugar pellet at the end of either arm of a T-shaped maze (Fig. 4A). The presence or absence of light delivery to the auditory cortex indicated the direction of the rewarded arm of the T-maze. The relationship between light delivery and the direction of the rewarded arm was constant within a mouse and counterbalanced. Mice receiving AAV-CaMKII-Arch-EYFP (Arch mice) or AAV-CaMKII-EYFP (EYFP mice) were exposed to 10 light-ON and 10 light-OFF trials per day. Mice received green light delivery to the auditory cortex throughout the light-ON trials. In the light-ON trials, from day 3, the Arch mice acquired reward with a higher success rate than the chance level of 50% (Fig. 4B). The success rate in the light-OFF trials also increased over days and reached a significant level on day 5. Because the EYFP mice performed the task at chance levels throughout the 5-d training (Fig. 4B), light delivery to the auditory cortex by itself was not enough to be a cue for the discrimination. These results indicate that mice can discriminate between presence and absence of neuronal silencing to find a reward.

Fig. 4.

Mice can find rewards based on optogenetic silencing. (A) Green light delivery to the auditory cortex indicated the direction of the baited arm of the T-maze. (B) Mice acquired the ability to find reward based on the presence or absence of optogenetic silencing (Arch, n = 10; EYFP, n = 8; ***P < 0.001 versus chance, Z-test for a proportion). (C) In Light ON trials, green light was delivered only at the start box. (D) Brief light delivery before the trial was sufficient for the mice to find the reward (Arch, n = 10; EYFP, n = 8; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 versus chance, Z-test for a proportion). Error bars indicate mean ± SEM.

Finally, we tested whether neuronal silencing can be stored as working memory. Mice that underwent the T-maze task described above were subjected to another 5 d of training, in which green light was delivered only in the start box for 10 s in the light-ON trials (Fig. 4C). The door was opened 3 s after the light delivery ended, and then the mice were allowed to choose either arm. In both the light-ON and -OFF trials from day 3, Arch mice exhibited significant success rates (Fig. 4D). The success rate of EYFP mice was comparable to chance levels over 5 d of training. These results indicate that brief neuronal silencing can be stored as a working memory and that mice can acquire a reward based on the working memory.

Discussion

In the present study, we used optogenetic silencing of a neuronal ensemble in the auditory cortex and found that mice exhibited a fear response to silencing that had been previously paired with footshock, and could find a reward based on the presence or absence of the silencing. The valence of the neuronal silencing was preserved for at least 30 d and was susceptible to extinction training. We also found that the neuronal silencing could be stored as working memory. These findings indicate that neuronal silencing without explicit activation in the cerebral cortex could lead to memory formation and behavioral expression.

Rebound excitation following inhibition is not involved in memory formation and retrieval driven by light illumination. Some studies suggest that optogenetic inhibition could be followed by rebound excitation (14, 15). Therefore, it might be argued that the excitation, instead of silencing, was associated with footshock in fear conditioning. However, this possibility is not the case because conditioned fear response was observed during light illumination but not after illumination. This result supports that neuronal silencing, but not rebound excitation, can be a cue for memory formation and retrieval.

Sensory information is likely to be encoded in inhibition of a subset of sensory cortical neurons, which can be used for a cognitive behavior. A previous study using single-unit recordings examined activity of auditory cortical neurons in response to a wide range of tone frequencies and found that tones suppress, as well as activate, a subset of those neurons (5). Their results suggest that different frequency bands of tone decrease different auditory cortical neurons. These findings indicate that auditory information might be encoded in not only activation but also inhibition of neuronal ensembles in the auditory cortex. However, whether the inhibition of those ensembles is used for information for a cognitive behavior was unclear. Therefore, in the current study, we tested whether the inhibition of those ensembles can be used for information for memory formation and retrieval. We found that mice receiving pairings of footshock with silencing of a neuronal ensemble exhibited fear responses to the subsequent silencing of the same ensemble. In addition, we silenced an ensemble in one side of the auditory cortex for conditioning and then examined fear responses to silencing of an ensemble in the other side of the auditory cortex. Silencing of the ensemble in the unconditioned side induced no fear response. Taken together, silencing of a specific neuronal ensemble in the auditory cortex could contribute to a behavior or perception driven by a specific sound.

Inhibitory interneurons in the auditory cortex probably silence neighboring excitatory neurons in a frequency-dependent manner and then contribute to behavioral expression. Indeed, parvalbumin- and somatostatin-expressing inhibitory neurons in the auditory cortex are well-tuned for frequency of tones (16, 17). Moreover, electrophysiological stimulation of putative inhibitory neurons in the somatosensory cortex affects behavioral responses in a mouse’s detection task (18, 19). Interestingly, stimulation effect of putative inhibitory neurons seems stronger than that of putative excitatory neurons (18). Therefore, auditory stimuli activate inhibitory interneurons in the auditory cortex in a frequency-dependent manner, which, in turn, inhibit their neighboring excitatory neurons, and this inhibition probably results in behavioral expression.

How do inhibited neurons convey information? Neurons generate ongoing action potential series even without explicit external stimuli (1, 2). Silencing of this spontaneous activity may be detected by the downstream neurons, and thereby may be decoded as a cue for memory formation and retrieval. The inhibitory interneurons in the downstream areas could be involved in detection of the silencing. Inhibitory interneurons in the basolateral amygdala (BLA) receive projections from the auditory cortex (20), and their inhibition on the BLA activity is involved in fear conditioning (21). Therefore, silencing of the auditory cortex could disinhibit BLA excitatory neurons via the inhibitory interneurons, and then this disinhibition might contribute to a cue for memory formation and retrieval. Although the role of inhibitory interneurons on appetitive learning remains less understood, inhibitory interneurons in the BLA, nucleus accumbens or ventral tegmental area might be involved in operant conditioning by neuronal silencing.

Comparison between behavioral effects of neuronal activation and silencing is interesting. Choi et al. showed that mice can detect ChR2 photostimulation of piriform neurons to elicit avoidance and appetitive behavior and that mice with fewer than 200 ChR2-expressing neurons failed to exhibit a behavior response to the photostimulation (22). In the current study, mice in which 37−114 neurons were labeled with mCherry in two 500 μm × 500 μm × 40 μm areas below the estimated position of the optical fiber tip showed conditioned fear, but mice in which 1−22 neurons were labeled with mCherry in the areas failed to show conditioned response. Given that the AAVs spread over longer than 400 μm (Fig. 3A), the required number of transfected cells for eliciting behavior is estimated to be at least 180 cells. Therefore, behavioral effects seem to require almost comparable number of silenced neurons to that of activated neurons. On the other hand, Huber et al. activated an average of 61 neurons (range 6–197) in the mouse primary somatosensory cortex by ChR2 photostimulation and showed that mice learn to detect the neuronal activation to obtain water reward (23). Thus, unification of behavioral task and target brain area will be helpful to precisely compare between the behavioral effects of neuronal silencing and activation.

In conclusion, we found that mice can report optogenetic silencing of auditory neuron ensembles by exhibiting fear responses or seeking a reward. Mice can also report that optogenetic activation of cortical neurons by avoidance and appetitive behavior (22, 23). Thus, stimulus-driven activation and inhibition of neuronal ensembles in the sensory cortex may together contribute a cognitive behavior. Further investigations into the effect of photoinhibition by different light intensity, duration, and delivery patterns on behavior and neuronal activity will be helpful to understand patterns of neuronal silencing available for perception.

Materials and Methods

Detailed experimental procedures are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Mice.

All experiments were approved by the animal experiment ethics committee at the University of Tokyo (approval number 24–10), and were in accordance with the University of Tokyo guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Adult male C57BL/6J mice (7–11 wk; SLC) were housed in groups of 3–4 and maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM), and provided with food and water ad libitum. Mice were housed individually after surgery.

Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors.

AAV5-CaMKII-eArch3.0-EYFP, AAV5-EF1a-DIO-eArch3.0-EYFP, AAV8-CaMKIIa-mCherry-IRES-Cre and AAV5-CaMKII-EYFP were purchased from the UNC Vector Core service (The University of North Carolina Gene Therapy Center).

Stereotaxic Surgery.

Mice were anesthetized using pentobarbital (2.5 mg/kg, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) and placed in a stereotaxic apparatus. The virus (1.0 μL per side) was injected into the bilateral auditory cortex (AP: −2.4 mm, LM: ±4.5 mm, DV: −3.0 mm) at a rate of 0.1 μL/min using glass pipettes. For expression of Arch in a small number of neurons in the auditory cortex, we bilaterally injected a mixture of AAV8-CaMKII-mCherry-Cre (0.02 μL per side), AAV5-EFf1a-DIO-eArch3.0-EYFP (0.5 μL per side), and PBS (0.48 μL per side). Glass pipettes were then left in place for 10 min and slowly withdrawn. Optical fibers [200 μm core diameter, 0.48 numerical aperture (NA), Thorabs], epoxied to ceramic zirconia ferrules, (Precision Fiber Products) were implanted bilaterally above the injection site (AP: −2.4 mm, LM: ±4.5 mm, DV: −2.7 mm). The optical fibers were secured to the skull using adhesive cement and a mixture of acrylic and dental cement. Behavioral and electrophysiological experiments were performed 2–3 wk after the surgery.

Fear Conditioning.

Fear conditioning was performed in a conditioning chamber (shape: square, wall: transparent, light: white, floor: grid). The chamber was cleaned with 70% ethanol before each session. In the fear conditioning for Fig. 2, mice underwent 16 pairings of 20-s green light delivery to the auditory cortex (561 nm wavelength, 9 mW output from fiber) with a 2-s footshock (0.6 mA), which coterminated with the light delivery in the conditioning chamber [intertrial interval (ITI): 60–120 s, total conditioning duration: 28 min]. Unpaired conditioning consisted of 16 temporally unpaired presentations of light delivery and footshock. In a testing session, the mice received 20-s light delivery five times (ITI: 40 s) in the testing chamber (shape: triangle, wall: white, light: red, floor: flat and white).

For testing remote memory and extinction of optogenetic conditioned fear, mice received 20-s light delivery 30 times per day on days 30–33. The averaged freezing time over every five light ON epochs was measured.

In the fear conditioning for Fig. 3, mice underwent 16 pairings of 20-s green light delivery to one side of the auditory cortex with a 2-s footshock, which coterminated with the light delivery in the conditioning chamber (ITI: 60–120 s, total conditioning duration: 28 min). On the next 2 d, mice received 20-s green light delivery five times (ITI: 40 s) to either the conditioned side or the unconditioned side of the auditory cortex.

Each session was video recorded for automatic scoring of freezing, according to a previously described method (24). Fear memory was assessed and expressed as the percentage of time the animal remained frozen, a commonly used parameter for measuring conditioned fear in mice. Freezing was defined as the absence of all movements, except those related to breathing.

T-Maze Test.

Mice were food-restricted to maintain 90% of their free-feeding weight throughout the behavioral test period to increase their motivation for food. Before the test, mice were habituated to the T-maze apparatus, consisting of a start (28 × 9 cm) and two goal arms (30 × 9 cm) with 15-cm-high walls, and sugar pellet rewards (TestDiet) over 3 d. In this habituation session, which was performed twice a day, mice were allowed to freely explore the T-maze for 5 min. Pellet rewards were placed at the T-junction and the end of each branch arm. On each test day, mice were imposed 20 trials that consisted of 10 Light ON and 10 Light OFF trials. The order of Light ON and OFF trials was pseudorandomly set, and repetitions of same-type trials were permitted a maximum of three times to avoid biases. The presence or absence of light delivery indicated the direction of the rewarded arm of the T-maze. The relationship between light delivery and the direction of the rewarded arm was constant within a mouse and counterbalanced. In Light ON trials, light illumination started when the mouse was placed on the start box of the T-maze. Ten seconds after light illumination, the door was opened so that the mouse could move and chose one of the T-maze arms. When the mouse chose the rewarded arm, it was allowed to eat the pellet reward until it was returned to the home cage. When the mouse chose the nonrewarded arm, it was blocked in the arm for 30 s and then returned to the home cage. Light delivery stopped when each trial ended. Light OFF trials were the same as the Light ON trials except for the light delivery. These sessions were repeated on 5 consecutive days. Three days after the above tests, the mice underwent 5 d of additional testing with transient light delivery. In this test, light delivery was presented only in the start box for 10 s. The door was opened 3 s after the light delivery ended. All other procedures were the same as those of the initial test.

Data Analysis.

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Tukey’s test after one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), repeated measures ANOVA, paired t tests, and Z tests were performed to identify significant differences.

SI Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry.

After anesthesia with diethyl ether, mice were transcardially perfused with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Brains were postfixed overnight, and subsequently transferred to successive 20% and 30% (wt/vol) sucrose dissolved in PBS. The brains were frozen, and coronal sections (40 μm) were prepared using a cryostat (HM520; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). EYFP was visualized with an anti-green fluorescent protein primary antibody (A-11120, 1:1,000; Life Technologies) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (A-11001, 1:1,000; Life Technologies). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst dye (1:1,000; Life Technologies).

Confocal Microscopy.

Images of auditory cortical neurons (2.3–2.5 mm posterior to the bregma, two slices per mouse) were acquired using a confocal microscope (CV1000; YOKOGAWA) at 20× magnification under an objective lens (NA, 1.3). Areas of analysis were z-sectioned in 1.6-μm optical sections. The region of interest was a 500 μm × 500 μm area below the estimated position of the optical fiber tip. Fluorescence images were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH). The nuclei in the auditory cortex were traced in the Hoechst channel using ImageJ software. Only cells that were presumptive neurons, with large nuclei stained diffusely with Hoechst, were included in the analysis. The traced regions were copied to a corresponding mCherry channel for analysis. The designation “mCherry positive (mCherry+)” was assigned to cells whose nuclei were entirely labeled with mCherry. Labels for mCherry were assigned by an experimenter blind to the behavioral conditions.

In Vitro Electrophysiology.

Mice were deeply anesthetized with diethyl ether and decapitated. Brains were removed quickly, and coronal slices (300 µm thick) containing the auditory cortex were prepared with a vibratome (VT 1200S, Leica) in ice-cold, oxygenated (95% O2/5% CO2) modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (mACSF) containing 222.1 mM sucrose, 27 mM NaHCO3, 1.4 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM KCl, 0.5 ascorbic acid, 1 mM CaCl2, and 7 mM MgSO4. The slices were then kept in a chamber containing oxygenated ACSF (127 mM NaCl, 1.6 mM KCl, 1.24 mM KH2PO4, 1.3 mM MgSO4, 2.4 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose). The temperature of the chamber was kept at 37 °C for 30 min and then returned to room temperature.

Slices were mounted in a recording chamber at 30–32 °C and perfused at a rate of 1.5–3 mL/min with ACSF bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed with glass microelectrodes (3–6 MΩ) filled with internal solution (135 mM K-gluconate, 4 mM KCl, 10 phosphocreatine-Na2, 10 mM Hepes, 4 mM MgATP, 0.3 mM Na2GTP; pH 7.2–7.3; 280–295 mOsm). Green light was emitted from a Mercury lamp (C-SHG-1; Nikon) and band-passed at 528–552 nm and illuminated through an objective lens. Maximal light power was 6 mW. Green light-induced currents were measured under the voltage clamp mode at a holding membrane potential of −70 mV. In an experiment for green light-induced inhibition of action potentials, 200 pA of current was injected for 10 s. Data were discarded if access resistance changed by more than 20% during an experiment. Data were sampled at 20 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz using an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments), DIGIDATA 1440A (Axon Instruments), and pClamp 10.2 (Molecular Devices). All data were acquired, stored, and analyzed using Clampex 10 (Molecular Devices), Clampfit (Molecular Devices), and MATLAB (The MathWorks).

In Vivo Electrophysiology.

Electrophysiological experiments from living mice were performed 7–8 wk after the injection of AAV5-CaMKII-eArch3.0-EYFP into the auditory cortex. Mice were anesthetized with urethane (2.0–2.2 g/kg, i.p.) and were fixed with a metal head-holding plate. A craniotomy (2 × 2 mm2, centered at the virus injection site) was made using a high speed drill and the dura was surgically removed. Two stainless screws were implanted in the bone above the cerebellum, served as ground and reference electrodes. An optical fiber (200 μm core diameter, 0.48 NA), epoxied to ceramic zirconia ferrules, was inserted into the craniotomized area at a depth of 200–600 μm at an angle of 20–27° toward the posterior direction in the sagittal plane, and an electrode assembly that consisted of four tetrodes was inserted into the same area to a depth of 600–950 μm at a speed of 10–30 μm/s. Tetrodes were constructed from 17 μm polyimide-coated platinum-iridium (90/10%) wire (California fine wire), and tetrode tips were plated with platinum to lower electrode impedances to 150–300 kΩ at 1 kHz. Eletrophysiological data were sampled using a Cereplex direct recording system (Blackrock). Unit activity was amplified and band-pass filtered at 600 Hz to 6 kHz. Spike waveforms above a trigger threshold (40 μV) were time-stamped and recorded at 30 kHz for 1.6 ms. After obtaining stable recordings of unit activity from the auditory cortex, a 10-s green light pulse (561 nm wavelength, 10 mW output from fiber) was delivered through the optical fiber at an intertrial interval of 180 s. After the recording, the recording device and the optical fiber were secured to the skull using adhesive cement for histological analysis. In the histological analysis, the mice were perfused transcardially with cold 4% PFA in 25 mM PBS and decapitated. The recording device and optical fiber were carefully removed from the brain 8–12 h after the fixation. The brains were coronally sectioned at a thickness of 100 μm. Recordings were included in the data analysis if the electrode position was involved in an EYFP-expressing area. Multiunit activity with an average firing rate of less than 3 Hz and waveforms longer than 200 μs were considered to be arising from putative excitatory cells and included in analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masanori Sakaguchi (University of Tsukuba) for technical advice on optogenetic experiments. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (25830002, to H.N.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas, “Mesoscopic Neurocircuitry” (23115101, to H.N.), “The Science of Mental Time” (26119507 to H.N. and 25119004 to Y.I.), and “Memory Dynamism” (26115509 to H.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1500869112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fiser J, Chiu C, Weliky M. Small modulation of ongoing cortical dynamics by sensory input during natural vision. Nature. 2004;431(7008):573–578. doi: 10.1038/nature02907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weliky M, Katz LC. Correlational structure of spontaneous neuronal activity in the developing lateral geniculate nucleus in vivo. Science. 1999;285(5427):599–604. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5427.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsodyks M, Kenet T, Grinvald A, Arieli A. Linking spontaneous activity of single cortical neurons and the underlying functional architecture. Science. 1999;286(5446):1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou Y, et al. Preceding inhibition silences layer 6 neurons in auditory cortex. Neuron. 2010;65(5):706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hromádka T, Deweese MR, Zador AM. Sparse representation of sounds in the unanesthetized auditory cortex. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(1):e16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72(2):231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pi H-J, et al. Cortical interneurons that specialize in disinhibitory control. Nature. 2013;503(7477):521–524. doi: 10.1038/nature12676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S-H, et al. Activation of specific interneurons improves V1 feature selectivity and visual perception. Nature. 2012;488(7411):379–383. doi: 10.1038/nature11312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang J, McFadden SL, Caspary D, Salvi R. Gamma-aminobutyric acid circuits shape response properties of auditory cortex neurons. Brain Res. 2002;944(1-2):219–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02926-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cardin JA, et al. Driving fast-spiking cells induces gamma rhythm and controls sensory responses. Nature. 2009;459(7247):663–667. doi: 10.1038/nature08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sohal VS, Zhang F, Yizhar O, Deisseroth K. Parvalbumin neurons and gamma rhythms enhance cortical circuit performance. Nature. 2009;459(7247):698–702. doi: 10.1038/nature07991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris KD, Mrsic-Flogel TD. Cortical connectivity and sensory coding. Nature. 2013;503(7474):51–58. doi: 10.1038/nature12654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chow BY, et al. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature. 2010;463(7277):98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature08652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura S, Baratta MV, Pomrenze MB, Dolzani SD, Cooper DC. High fidelity optogenetic control of individual prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons in vivo. F1000 Res. 2012;1:7. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.1-7.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith KS, Virkud A, Deisseroth K, Graybiel AM. Reversible online control of habitual behavior by optogenetic perturbation of medial prefrontal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(46):18932–18937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216264109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore AK, Wehr M. Parvalbumin-expressing inhibitory interneurons in auditory cortex are well-tuned for frequency. J Neurosci. 2013;33(34):13713–13723. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0663-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L-Y, et al. Differential receptive field properties of parvalbumin and somatostatin inhibitory neurons in mouse auditory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2014;25(7):1782–1791. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houweling AR, Brecht M. Behavioural report of single neuron stimulation in somatosensory cortex. Nature. 2008;451(7174):65–68. doi: 10.1038/nature06447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doron G, von Heimendahl M, Schlattmann P, Houweling AR, Brecht M. Spiking irregularity and frequency modulate the behavioral report of single-neuron stimulation. Neuron. 2014;81(3):653–663. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sah P, Faber ESL, Lopez De Armentia M, Power J. The amygdaloid complex: anatomy and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2003;83(3):803–834. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00002.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff SBE, et al. Amygdala interneuron subtypes control fear learning through disinhibition. Nature. 2014;509(7501):453–458. doi: 10.1038/nature13258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi GB, et al. Driving opposing behaviors with ensembles of piriform neurons. Cell. 2011;146(6):1004–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber D, et al. Sparse optical microstimulation in barrel cortex drives learned behaviour in freely moving mice. Nature. 2008;451(7174):61–64. doi: 10.1038/nature06445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nomura H, Matsuki N. Ethanol enhances reactivated fear memories. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(12):2912–2921. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]