Abstract

A new emphasis has been put on the role of the gastrointestinal (GI) ecosystem in autoimmune diseases; however, there is limited knowledge about its role in type 1 diabetes (T1D). Distinct differences have been observed in intestinal permeability, epithelial barrier function, commensal microbiota, and mucosal innate and adaptive immunity of patients and animals with T1D, when compared to healthy controls. The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse and the BioBreeding diabetes prone (BBdp) rat are the most commonly used models to study T1D pathogenesis. With the increasing awareness of the importance of the GI ecosystem in systemic disease, it is critical to understand the basics, as well as the similarities and differences between rat and mouse models and human patients. This review examines the current knowledge of the role of the GI ecosystem in T1D and indicates the extensive opportunities for further investigation that could lead to biomarkers and therapeutic interventions for disease prevention and/or modulation.

Introduction

The importance of the gastrointestinal (GI) ecosystem in shaping systemic immunity and in influencing autoimmune disease has become a major area of research (1–3). One such disease appears to have a GI link is type 1 diabetes (T1D), as serum antibodies to dietary cow’s milk protein are detected in patients with T1D and there is a strong correlation between Celiac disease (CD; an autoimmune disorder due to immune reactivity to foods containing gluten) and T1D (4, 5). The common mechanism is an alteration in GI barrier function, which allows food proteins/antigens to induce a mucosal and systemic immune response. New therapeutic options, such as fecal transplants, that can manipulate the GI ecosystem and influence subsequent immune responses are now in clinical use for Clostridium difficile infection and are under evaluation for multiple other diseases (6, 7). In order to evaluate the role of therapeutic manipulation of the GI ecosystem in prevention of T1D, the similarities of the GI ecosystem and the strengths, and weaknesses of the commonly used animal models (the non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse and the BioBreeding diabetes prone (BBdp) rat) must be determined.

The intestinal barrier is composed of multiple components, which together form a selective blockade. Small molecules and antigens can cross this barrier via the paracellular or the transcellular route. The paracellular pathway allows the passage of small molecules that are <600 Da. Patients with active CD have decreased expression of tight junction proteins (TJPs), which leads to increased paracellular permeability (8). Paracellular permeability is also increased in T1D and pre-diabetic patients (9, 10). The transcellular pathway allows for the passage of larger molecules, even whole bacteria, through epithelial cells (8). Typically only 0.1% of the original antigen transcytosed reaches the serosal compartment, highlighting the effectiveness of an intact intestinal barrier (11). Antigens that manage to avoid degradation in epithelial lysosomal compartments have the potential to be immunogenic (8, 11). This can be modeled in CD patients, as patients with active CD given a gliadin monomer will have detectable levels of the antigen in their serum, while patients with inactive disease do not (8, 12). Despite the strong correlation between T1D and CD/altered intestinal permeability, data from both the BABYDIET study and the TRIGR study concluded that altering the diet did not lower the incidence of T1D in the subjects being monitored (13, 14).

The paracellular and transcellular pathways are not the only components of the intestinal barrier that prevent small molecules and antigens from crossing the barrier. Other factors that contribute include the production of mucins and antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), innate and adaptive immunity, and the presence of luminal commensal microbiota. Mucins are complex glycoproteins secreted by epithelial cells that function to prevent antigens from reaching the epithelium by forming a physiochemical barrier (15, 16). GI mucus is composed of two layers: i) a thin sterile layer that covers the epithelial surface and ii) a thick outer layer that contains commensal bacteria (17). Damage to or alterations in the outer layer allows bacteria (commensal and pathogenic) to come into contact with epithelial cells, leading to inflammation (16, 17). Probiotic strains of bacteria, such as Lactobacillus plantarum, have been shown to be capable of inducing mucin production and therefore preventing pathogenic Escherichia coli from breaching the intestinal barrier (15). Along with mucin production, commensal microbiota are also essential for maintaining intestinal homeostasis through colonization resistance, preventing immunogenic antigens from reaching the epithelial barrier (18). The importance of a healthy microbiota can be seen in human subjects who have recently undergone a fecal transplant after suffering from Clostridium difficile infection. After fecal transplant the C. difficile bacteria is replaced with a normal microbiota and patient health is restored (7). It has been speculated that one way commensal populations are maintained and regulated is through the production of AMPs (19). These AMPs are the primary defense against pathogenic bacteria and allow commensal populations to remain in their niche.

With its high continuous exposure to commensal microbiota and food antigens, the ability of the mucosal immune system to respond in a dampened or regulatory manner to luminal antigens is essential. To achieve this homeostasis, dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and cytokines are all responsible for controlling the response of effector T-cells to commensal and food antigens that reach the intestinal barrier (20–22).

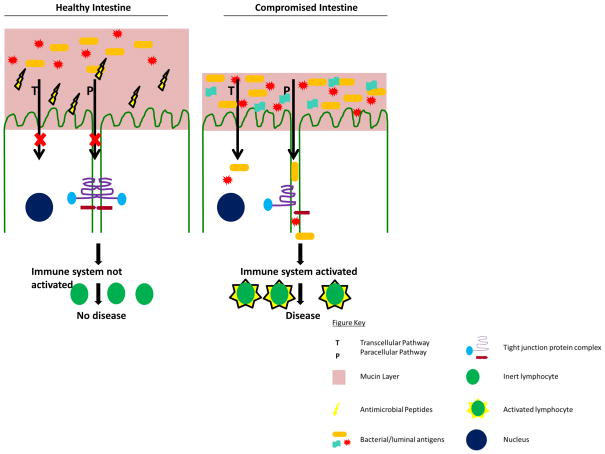

This review will explore what is known about these components and how alterations to them may lead to T1D in both human patients and animal models of the disease (Fig. 1). The NOD mouse and the BBdp rat models have a disease progression similar to humans, as they develop peri-insulitis, followed by insulitis, and subsequently diabetes (23, 24). Both models also have the same major histocompatibility complex polymorphism that is associated with T1D in humans and both have been reported to have a leaky gut, as is further described below (25–27). When using either the NOD or BBdp model it is essential to consider that effective therapies in these models have not translated to human treatments, but they still continue to reveal important insight into disease pathogenesis (28, 29).

Figure 1.

Intestinal homeostasis is maintained by a healthy microbial population, mucin layer, antimicrobial peptides, and tight junction proteins. Together these factors prevent or limit the exposure of bacteria and luminal antigens to the epithelium, which result in non-activated or tolerant immune system. In a diseased state when alterations are made to the microbial population, mucin layer, antimicrobial peptides, and tight junction proteins, bacteria and luminal antigens are able cross the epithelial layer. Once bacteria and other luminal antigens have crossed the epithelial layer the immune system is activated, leading to diseases, such as type 1 diabetes.

Intestinal Permeability

Altered intestinal permeability has been shown to play a role in multiple autoimmune diseases including CD and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (8, 30). The concept of a leaky gut has now been associated T1D, as patients with T1D and their relatives have more permeable guts than controls (4, 25, 31–33). In addition, both BBdp rats and NOD mice have an increase in intestinal permeability when compared to their respective controls (26, 34).

Permeability has been assessed in multiple ways in T1D animal models and human patients (Table 1). Paracellular permeability is determined by the pore size of TJPs, with different combinations of TJPs determining a large versus small pore size (11). Two groups of TJPs, the Claudins (Cldn) and Occludin (Ocln) are considered to be master regulators of permeability due to their ability to open and close paracellular junctions (25). The expression levels of TJPs can be determined by western blot and/or PCR and decreases in expression can indicate an increase in paracellular permeability (11, 26, 35). However, actual functional permeability can be ascertained by the lactulose (LA)/mannitol (MA) ratio, FITC-dextran serum levels, or bacterial translocation into draining lymph nodes. The LA/MA assay utilizes high performance liquid chromatography to measure the LA and MA in urine after oral administration. MA is a small sugar that permeates the barrier through a transcellular pathway, while LA is a larger sugar that permeates the barrier through the paracellular pathway (34, 36). The LA/MA ratio has been used in human subjects, where research has shown that diabetic patients have a higher LA/MA ratio compared to healthy controls (10). However, there are limitations to the LA/MA ratio, as the linear correlation is poor, as the correlation worsens as the molecular size of the solute increases (11). Like LA and MA, FITC-dextran is another sugar that can be used to measure paracellular permeability in the small intestine of animal models. FITC-dextran is a fluorescent sugar that is given by oral gavage or enema and will leak across the gut if the intestinal barrier is permeable. Another method to measure transcellular permeability is giving mice an oral gavage of bacteria and then removing lymph nodes and culturing homogenate on agar plates and counting colonies to determine actual bacterial translocation (27). One important caveat to any of these measurements is that they do not take into account gastrointestinal motility or the body distribution of the chosen tracer (11).

Table 1.

Alterations in Gastrointestinal Permeability in Patients and Models of Type 1 Diabetes

| Measure of Permeability | NOD | BBdp | Human |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactulose/mannitol (LA/MA) | N/A | Lower LA/MA ratio in BBdp rats that are on a diabetic resistant diet (36) | Higher LA/MA ratio in T1D patients compared to healthy controls (31) |

| FITC-dextran | Increased serum levels of FITC-dextran compared to NOR and C57BL/6 (25) | Not commonly used to measure permeability in BB rats | Not commonly used to measure permeability in human subjects |

| Bacterial Translocation | Bacterial translocation increased to MLN and pancreatic lymph node after C. rodentium infection in NOD mice compared to C57BL/6 mice (27) | N/A | N/A |

| Tight Junction Proteins (TJPs) | N/A | Lower protein expression of Cldn1 compared to Wistar rats (26) Inoculation with L. johnsonii increased mRNA expression of Cldn1, but decreases expression of Ocln (35) |

Increased mRNA expression of Cldn1 from intestinal biopsies of diabetic patients (9) Decreased mRNA expression of Cldn2 from intestinal biopsies of diabetic patients (9) |

| Zonulin | N/A | High levels of circulating zonulin precede T1D (38) Zonulin inhibitor lowers the incidence of T1D (38) |

Zonulin levels are elevated in T1D patients (9) Non-diabetic 1st degree relatives of patients with T1D have increased zonulin levels (9) |

A natural indicator of intestinal permeability is increased zonulin levels in serum (37, 38). Zonulin was first identified when Vibrio cholera was found to produce zonula occludens toxin (Zot). Zot was shown to interact with TJPs and increase intestinal permeability (37). A human analogue was identified named zonulin (also known as haptoglobin) and its effects are primarily in the small intestine (37, 39). The physiologic role of zonulin is still largely unknown, but it has been speculated that it may regulate fluid movement in the small intestine, specifically opening TJs to allow the secretion of water into the intestinal lumen, flushing away bacteria (40).

At 12 weeks of age NOD mice have increased intestinal permeability compared to the non-obese diabetic-resistant (NOR) and C57BL/6 strains of mice when using FITC-dextran as a measure of permeability (27). In the NOD mouse, microbiota can also lead to selective alterations in intestinal permeability. The administration of Citrobacter rodentium alters the transcellular pathway and leads to a higher bacterial translocation of C. rodentium to the mesenteric lymph node (MLN) and pancreatic lymph node (PLN) of NOD mice when compared to C57BL/6 mice (27). Both BBdp and BioBreeding diabetic resistant rats (BBdr) rats have lower levels of the TJP Cldn1 compared to non-diabetic Wistar rats, indicating a susceptibility to T1D is associated with increased intestinal permeability and a decrease in expression of the TJP, Cldn1 (26). In rats that have been inoculated with Lactobacillus johnsonii there is a higher expression (mRNA) of the TJP Cldn1 in BBdp rats that do not have diabetes compared to BBdp rats that do have diabetes (35). In contrast to the BB rat, limited data on human subjects shows an increase in mRNA expression of Cldn1 from intestinal biopsies of diabetic patients compared to healthy controls (9). The discrepancies in Cldn1 expression between BB rats and humans may indicate that the role of TJPs during the pathogenesis of T1D differs between species and requires further investigation.

In Inflammatory diseases of the gut, such as CD, patients have higher zonulin levels in their intestinal submucosa compared to control patients (41). Increases in zonulin have also been shown to precede the development of T1D in the BBdp rat (38). In BBdp rats luminal levels of zonulin increase between 20–70 days when compared to BBdr control rats or BBdp rats that do not go on to develop T1D (38). The effects of zonulin can be prevented with a zonulin inhibitor, which lowers the incidence of T1D by 50% in the BBdp rat (38). In humans, not only have zonulin levels been shown to be increased in TID patients, but levels are also elevated in relatives of T1D patients compared to healthy controls (9). One potential mechanism is that increased intestinal permeability allows antigens to drain into the PLN, where they could potentially activate lymphocytes that have access to the pancreas (42, 43). These activated lymphocytes could then cause β-cell damage leading to T1D. Regardless of species, current data suggests the importance of intestinal permeability in T1D and implies that exploration of potential therapeutics to decrease intestinal permeability in the pre-diabetic state may be worthy of future exploration.

Diet has been shown to reduce T1D incidence in animal models of the disease (Table 2) (34, 44–46). The effects of diet on permeability are still under investigation with some research pointing to a decrease in permeability, while other data points to no change in permeability (34, 36). A hydrolysed casein (HC) diet is able to restore intestinal integrity, as measured by the LA/MA ratio, while also lowering zonulin levels in the BBdp rat (36). HC diets lead to a 60% decrease in diabetes incidence in BBdp rats, when compared to BBdp rats on a control diet (34). BBdp rats on a HC diet have elevated levels of Cldn1 expression in the ileum leading to a reduction in permeability, this reduction in permeability may be increasing overall intestinal health, which leads to a reduction in T1D incidence (36). Unfortunately, the effect of diet on epithelial permeability in the NOD mouse or in human patients has not been thoroughly investigated. Importantly, alterations in the intestinal microbiota induced by dietary alterations need to be further explored in both animal models and humans, as it is clear that microbial components can have direct effects on the intestinal barrier.

Table 2.

Diet Effects on the GI Ecosystem in Models of Type 1 Diabetes

| Intestinal alteration | Diet Induced |

|---|---|

| Permeability | Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) from the bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates decrease colonic permeability in BBdp rats (48). Hydrolysed casein (HC) diet restores intestinal permeability, as measured by LA/MA, zonulin levels, and Claudin 1 levels in the BBdp rat. Diabetes incidence decreased by 60% in BBdp rats (34,36). |

| Antimicrobial Peptides and Mucins | HC diet in the BBdp rat up regulates the gene expression of the antimicrobial peptide (AMP) cathelicidin (CRAMP) (45). The plant based diabetes promoting (NTP diet) reduces mucins at a greater level in the BBdp rat compared to the BBdr rat (44). Probiotic VSL#3 increases mucin (MUC2) expression in the colon of Wistar rats and increases expression of the AMP, β-defensin 2 in Caco-2 cells (105,106). |

| Mucosal Immunity | Gluten based diabetes promoting diet, leads to a decrease in Tregs in the lamina propria of NOD mice (77). |

| Microbiota | The probiotic VSL#3 lowers the incidence of diabetes in NOD mice (104). Acidified and neutral H2O alters the microbiota in NOD mice and alters diabetes incidence (90,107). |

Past research has shown the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced by bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates in the colon can affect permeability (47). Permeability in the BBdp rat can be altered by direct administration of the SCFA, sodium butyrate, to rats between 10–23 days of age, leading to a decrease in distal colon permeability compared to control rats and a delay in the onset of diabetes (48). Butyrate is most likely altering TJPs as it has been shown to play a role in proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and maintenance of tight junctions in epithelial cells (48). However, in C57BL/6 mice, butyrate has also been shown to increase insulin sensitivity and therefore there may be several mechanisms playing a role in any impact of butyrate in T1D (48, 49). The ability of butyrate to delay or prevent T1D in NOD mice and humans requires further investigation.

Antimicrobial Peptides and Mucins

Additional factors that contribute to barrier function are mucins produced by goblet cells and enterocytes, and AMPs produced by enterocytes and Paneth cells within the intestinal tract. Human and rat neutrophils are also being capable of producing AMPs, while murine neutrophils cannot (50). Mucins are complex glycoproteins that protect mucosal epithelial cells either through steric hindrance, forming a physiochemical barrier, or through specific mucin-bacteria interactions (15). In the human, mouse, and rat intestine the majority of the secreted mucin layer consists of MUC2 or its equivalent, while MUC1, MUC3A/B, MUC12, MUC13 and MUC17, or their equivalents, are expressed on the epithelial cell surface (16, 51, 52). Goblet cells also produce a small peptide known as trefoil factor 3 or intestinal trefoil factor (TFF3/ITF) (52). TFF3 is thought to have the ability to increase the viscosity of MUC2 by stabilizing the mucin and thus helping to protect the epithelial cell surface (52). Interestingly TFF3 has also been shown to induce β-cell proliferation in rat and human islets (53). TFF3 is not the only trefoil factor that could potentially affect T1D. Trefoil Factor 2 (TFF2, also known as spasmolytic polypeptide) is secreted by gastric mucous neck cells and has been shown to induce β-cell proliferation in mouse islets (54). The interaction of trefoil factors with mucins in diabetes is still an unexplored area, but could represent a therapeutic pathway to alter disease incidence.

One main type of AMP is the defensins, which are cationic peptides that kill bacteria by disrupting the bacterial cell membrane. There are two main classes of defensins, α and β (50). α-defensins are primarily expressed in the small intestine by Paneth cells located in the crypts, but can also be produced by neutrophils and macrophages (55, 56). β-defensins are expressed by almost every epithelial cell in the small intestine and colon, but there is little expression in the crypts of the small intestine (57). In mice and rats these defensins are referred to as cryptdins (58). Both α and β-defensin expression have been shown to be attenuated in the ileum and colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, however the role of defensins in T1D is still widely unknown (59). One recent report has indicated that in patients with T1D a specific genotype of defensin β-1 may result in decreased defensin production (60). In addition, studies in the BBdp rat have shown that a HC diet (which lowers the incidence of T1D) upregulates the gene expression of another AMP, cathelicidin (CRAMP), in the ileum and jejunum (45, 61). In mice, CRAMP has been shown to regulate pathogenic C. rodentium colonization and in humans it regulates pathogenic E. coli, indicating that some of its effects may be via its ability to shape the luminal microbiota (61). Like the defensins, there is still much that is unknown about the role of CRAMP in the progression and pathogenesis of T1D. Inducing expression of CRAMP in human subjects using phenylbutyrate (PBA) represents a potential therapeutic modulator of the commensal microbiota that could be tested in T1D patients (62, 63). The importance of AMPs and mucins in shaping the microbiota is widely accepted, but their role in disease pathogenesis is still not understood. As research continues to uncover the role of the microbiome in T1D, AMPs and mucins will require further exploration as a potential area of future experimental focus.

When BBdp rats develop diabetes they have a lower number of goblet cells when compared to BBdr rats and BBdp rats that have been treated with L. johnsonii (which delays T1D development) (35). This indicates that mucins play a protective role in diabetes and may be lowering the incidence of disease and that specific strains of bacteria can alter mucin expression. When the Lactobacillus strains Lp299v and LrGG are co-inucbated with the colonic cell line (HT29), an increased expression of MUC3 mRNA can be detected in the HT29 cells (15). This increased MUC3 production then inhibits the adherence of pathogenic E. coli to HT29 cells (15). This inhibition of bacterial adherence can prevent bacterial antigens from crossing the intestinal barrier and activating the immune system, which could lead to an altered incidence of diabetes. BBdp and BBdr rats on a plant based diabetes promoting diet (NTP diet) also have reduced levels of mucins, with a more dramatic affect seen in the diabetic BBdp rat (44, 64). In addition, the importance of mucins has also been linked to the development of T1D in humans, as patients with T1D are reported to have a lower levels of lactate and butyrate producing bacteria, which leads to a decrease in mucin synthesis. This allows the intestinal epithelium and the mucosal immune system to be exposed to an increased number of luminal antigens (65).

Mucosal Immunity

Over 15 years ago, the observation was made that the jejuna of patients with T1D showed increased α4β7+ cells in their intestinal lamina propria, a sign of immune activation (66). Cells expressing these same mucosal addressins and integrins are components of islet-infiltrating T-cells, implying a link between the mucosal immune system and the pancreas (67, 68). Intriguingly, it has now been shown that the PLNs can sample not only self-antigens from the pancreas, but are also exposed to microbial products from the GI track (43). In addition, in young NOD-mice, T-cells with the most diabetogenic potential were primarily found in gut-associated lymph nodes (69). In a normal mouse (or human), there appears to be tight mucosal compartmentalization of microbial antigens by the mucosal immune system, which limits this systemic exposure (70). However, in animals/humans who have altered intestinal barrier permeability (T1D), the microbial products can freely cross the intestinal barrier and reach draining lymph nodes, including PLNs (71). This has been demonstrated in patients with T1D, where systemic immune responses to cow’s milk proteins have been observed (4).

In addition to these draining lymph nodes, there are two other organized lymphoid components in the gastrointestinal immune system, the lamina propria and intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) (72). It has been reported that a deficiency in IELs occurs prior to the onset of diabetes in BBdp rats and that neonatal thymectomy (which depletes both natural Tregs and IELs) in NOD mice accelerates diabetes (73, 74). Transfer of IELs into thymectomized NOD mice can prevent diabetes, indicating that these mucosal immune cells play a key role in maintaining tolerance to pancreatic antigens (73). Decreased numbers of Tregs in the lamina propria is a consistent finding in the small intestine of both patients with T1D and in NOD mice (75–77). However, it is unclear if this decrease is primarily in natural Tregs (derived from the thymus) or is also due to an inability to make induced Tregs. However, alterations in Treg populations are not the only mucosal immune abnormalities noted in T1D. Colonic T-cells express higher levels of both IL-17 and IFNγ and MLNs have increased Th17 and Th1 effector T cells (46, 75, 78). In addition, children with T1D have been shown to have upregulaton of Th17 cells in peripheral blood (79). However, the role of IL17 in T1D is controversial, as it has also been shown that BBdp rats that are rendered diabetes-resistant by treatment with L. johnsonni strain N6.2 have a Th17 bias (80). The GI ecosystem is a stable alliance between resident microbiota, immune mediators, and the epithelial barrier (72) and it is clear that diet and the environment can directly alter the microbiota. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain what effects are due to mucosal inflammation and what are secondary to altered composition of the resident microbiota.

Microbiota

Recent reviews have emphasized the importance of microbiota in affecting the disease incidence of T1D across species (35, 81–90). It was originally thought that germ free NOD mice developed diabetes at a higher incidence rate than mice with intestinal flora (91). However, recent reports have found that germ free animals develop T1D at the same rate as specific pathogen free (SPF) mice and that it is the presence of certain bacteria that is needed to prevent diabetes (75, 92). Multiple reports have reported alterations in the microbiota between healthy children and children with T1D (93–96). Human data has indicated that healthy subjects have a higher percentage of butyrate-producing and mucin-degrading bacteria from the generas, Prevotella and Akkermansia, compared to T1D subjects (65). This is in contrast to data in the BBdr rat that shows a reduction in mucin increases T1D susceptibility (44, 64). These different results regarding mucin levels may be explained by variations in commensal populations and differences in immune responses to antigens between diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Researchers have also followed children that are at a high genetic risk for developing T1D and shown that they have a decrease in intestinal microbiota diversity compared to controls (97). These children at risk for T1D also have an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes compared to age matched healthy controls (97). While observations in subjects who have T1D must be interpreted with caution due to the possible confounding effects of the disease itself, the observations from Giongo et al. suggest the composition of gut microbiota may play a role in development of autoimmunity and T1D (97).

In NOD mice, segmented filamentous bacteria (SFB), have been shown to co-segregate with diabetes protection in male, but not female, mice and cause a dominance of Th17 (IL-17 producing) cells in the small intestine lamina propria (98). The potential role of SFB in altering T1D incidence BBdp rats is still unknown, but data has shown that as these rats progress towards diabetes their percentages of circulating IL-17 producing T-cells increases compared to BBdr rats (99). Human patients with T1D have a higher number circulating IL-17 cells compared to recent onset and healthy control patients (100). Diabetic subjects also have a higher percentage of Th17 along with defective Tregs in their pancreatic lymph node compared to healthy subjects (101). Much like the BB rat, the SFB colonization status of patients with and without T1D has yet to be investigated, and information regarding the presence of SFB in the human GI track is limited (102). Although the role of Th17 cells in diabetes is not yet clear, varying levels of IL-17 amongst patients and control subjects, indicates that there is most likely a difference in SFB colonization (or in colonization of a similar microbiota that can induce IL-17 production) between healthy and diseased groups.

The impact of microbiota on diabetes incidence is evident in experimental models that have been treated with antibiotics. In NOD mice the incidence of T1D can be significantly lowered when mice are treated with antibiotics (89, 103). One of these antibiotics is vancomycin, which targets gram-positive bacteria. When administered to NOD pups at birth until weaning, vancomycin as expected, led to a depletion of gram-positive bacteria, but also surprisingly led to a depletion of gram-negative bacteria in the gut of the NOD mouse(89). The reduction of both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria leads to the emergence of Akkermansia muciniphila, which correlates with a lowering in the incidence of T1D (89). Similar effects of antibiotics on the incidence of T1D on the BBdp rat have also been reported (88, 104). BBdp rats given a combination antibiotic treatment of sulphamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and colistine sulphate to reduce gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria have a lowered incidence of T1D (88). The antibiotic-treated BBdp rats also have a reduced level of Bacteroides compared to rats that did develop diabetes (88). Although the microbiota was not examined, treatment of BBdp rats with the anti-staphylococcal drug fusidin also reduced the incidence of T1D in treated groups (104). Interestingly in humans treated with a variety of antibiotics it has been shown that their mucin profile resembled that of a germfree rat, which differed from the mucin profile associated with the presence of gut microbiota as shown by running mucins isolated from human subjects and germfree rats on electrophoresis gels and comparing banding patterns (105). It was speculated that antibiotics were altering mucin profiles by removing mucin degraders Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, and Bifidobacterium from the GI system and we speculate that this could be another contributing factor to antibiotics altering the incidence of diabetes (105).

The importance of specific commensal microbiota in the gut in the determination of T1D incidence has been most widely studied in the NOD mouse. The administration the probiotic mixture VSL#3 (which contains multiple species of bifidobacteria, multiple species of lactobacillus, and Streptococcus salivarius) to NOD mice lowers the incidence of T1D (106). NOD mice that are given VSL#3 have increased levels of IL-10 in Peyer’s patches, the spleen, and the pancreas, likely leading to suppression of effector T-cells in these areas (106). When administered to Wistar rats, VSL#3 also induced an increase in colon MUC2 expression, which could further explain the protective nature of VSL#3 in diabetes (107). VSL#3 also has been shown to increase human β-defensin 2 in Caco-2 cells and this increase in AMPs represents another possible mechanism by which VSL#3 helps lower the incidence of diabetes (108).

The use of antibiotics and direct administration of bacteria is not the only way to potentially affect the microbiota and alter the incidence of T1D. Two reports have now demonstrated that slight changes in the acidity of the drinking water can dramatically alter the commensal microbiota and the incidence of T1D in the NOD model (90, 109). One group has recently shown that NOD male commensal microbiota were generally shown to have higher levels of Firmicutes and lower levels of Bacteroidetes compared to NOD female mice (87). This difference in microbiota between male and female NOD mice resulted in a higher level of circulating testosterone in male mice, which correlates with a decrease in insulitis resulting in a decreased incidence of T1D in the NOD male mouse compared to the females (87). In the BBdp rat the incidence of diabetes can be lowered when L. johnsonii N6.2 is given daily to pups by oral gavage (35). The administration of L. johnsonii N6.2 results in an increase in mRNA levels of the TJP Cldn1 and decrease in Ocln. Along with alterations in TJPs, BBdp rats that are given L. johnsonii N6.2 have decreased levels of the inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, which indicates a shift in the mucosal and systemic immune response (35). It has also been shown that in BBdp rats that do not develop T1D there is an increase in Lactobacillus populations in the ileum (35). All of these results indicate that alterations in microbiota may have a significant impact on the incidence of T1D and imply that these types of manipulations deserve further study and may lead to therapeutic interventions in the future.

Conclusions and Future Directions

The available data from humans and animal models all indicates that altered intestinal permeability, barrier function, commensal microbiota, and mucosal immunity may contribute to the susceptibility and pathogenesis of T1D (Fig. 1). Alterations in intestinal permeability have been attributed to variances in TJPs in the BB rat and humans (9, 35). Low doses of butyrate in the BB rat can tighten tight junctions and have beneficial effects on T1D; however, it is not known if butyrate can alter TJPs in human subjects and NOD mice (48, 49). Further research into the therapeutic effects of butyrate or other SCFAs on disease incidence in humans and mice is required. Elevated zonulin levels have been directly linked to an increased incidence of T1D in humans and BB rats, but levels have not been measured in NOD mice. Investigating the role of zonulin in the NOD mouse will allow investigators to better understand its importance as a biomarker in human disease. The importance of intestinal permeability in all models of T1D is becoming more appreciated, but the use of controls with similar alterations in permeability, but no disease progression (such as the NOR mouse) are still underutilized.

The role of other components of the epithelial barrier in T1D still requires a great deal of investigation in both animal models and humans. AMPs need to be a major focus of investigation, as the importance of the microbiota in diabetes and other autoimmune diseases becomes more appreciated. In the BBdp rats increased expression of CRAMP is associated with a decreased incidence of T1D. Increases in β-defensins can be detected in Caco-2 cells after administration of the probiotic VSL#3, however it is unknown if the same effect would be seen in vivo when given to mice, rats, and humans (108). Although the role of AMPs in T1D is still unclear, mucins appear to play a major role in T1D disease development. Administration of VSL#3 in Wistar rats induces an increase in MUC2 in the colon of these rats and if increases in MUC2 are shown to be protective in diabetes, this may represent a possible preventative treatment (107).

Dysbiosis has been reported in humans with T1D and manipulation of the microbiota in animal models can have positive effects on disease incidence (87, 106, 108). The investigation of the role of hyperglycemia in modulating commensal microbiota will be required to better understand comparisons between bacteria from healthy and diabetic individuals. Research by Claudino, M et al. shows that hyperglycemia over a prolonged period does not significantly alter the oral microbiota in diabetic rats, but the effect on the intestinal microbiota requires investigation (110). The manipulation of microbiota in human subjects is an important avenue that will require future exploration for the prevention of T1D in susceptible individuals. In the US clinical trials have begun at the University of Pittsburgh examining the ability of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) to treat inflammatory bowel disease in patients ages 2–22 (clinicaltrials.gov). The emerging field of FMT may now allow for studies of this aspect of the pathogenesis of T1D in the near future (6, 7). In children who are at risk for T1D there is an increase in Bacteroidetes and a decrease in Firmicutes, but it is unknown if these shifts represent appropriate biomarkers to inform clinicians regarding which pre-diabetic human patients could enter into fecal transplant trials. To date, altering disease incidence through manipulation of the microbiota has not been attempted in pre-diabetic human subjects (97). An alternative to microbial manipulation in the treatment of T1D is the reversal of intestinal permeability through targeting of TJPs. Recently in mice the degradation of TJPs was inhibited using siRNA targeting ERK1/2, a downstream signaling protein of TNF-α (111). The use of siRNA may provide a viable treatment to reverse intestinal permeability in patients that are predisposed to T1D and lower disease incidence.

In summary, the direct cause of T1D is destruction of the pancreatic β-cells by the immune system. However, it is now clear that altered intestinal permeability, barrier function, and commensal microbiota may all contribute to the dysfunction of the mucosal and systemic immune system that is seen in the disease. The understanding of how the GI ecosystem influences the systemic immune system must be thoroughly mapped out in mouse and rat models, and in human subjects to adequately understand the mechanisms of T1D disease initiation.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Support: This study was supported in part by the NIH grant P01 DK071176, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant #36-2008-930, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of American Grant #26971, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Digestive Diseases Research Development Center grant P30 DK064400. Aspects of this project were conducted in biomedical research space that was constructed with funds supported in part by NIH grant C06RR020136.

References

- 1.Kamada N, Nunez G. Regulation of the immune system by the resident intestinal bacteria. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1477–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray K. Microbiota: Tolerating gluten--a role for gut microbiota in celiac disease? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:242. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaarala O, Atkinson MA, Neu J. The “perfect storm” for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57:2555–62. doi: 10.2337/db08-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luopajarvi K, Savilahti E, Virtanen SM, Ilonen J, Knip M, Akerblom HK, et al. Enhanced levels of cow’s milk antibodies in infancy in children who develop type 1 diabetes later in childhood. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:434–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00413.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuppan D, Hahn EG. Celiac disease and its link to type 1 diabetes mellitus. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism: JPEM. 2001;14 (Suppl 1):597–605. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.s1.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrof EO, Khoruts A. From stool transplants to next-generation microbiota therapeutics. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1573–82. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youngster I, Russell GH, Pindar C, Ziv-Baran T, Sauk J, Hohmann EL. Oral, capsulized, frozen fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2014;312:1772–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyman M, Abed J, Lebreton C, Cerf-Bensussan N. Intestinal permeability in coeliac disease: insight into mechanisms and relevance to pathogenesis. Gut. 2012;61:1355–64. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sapone A, de Magistris L, Pietzak M, Clemente MG, Tripathi A, Cucca F, et al. Zonulin upregulation is associated with increased gut permeability in subjects with type 1 diabetes and their relatives. Diabetes. 2006;55:1443–9. doi: 10.2337/db05-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosi E, Molteni L, Radaelli MG, Folini L, Fermo I, Bazzigaluppi E, et al. Increased intestinal permeability precedes clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2824–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menard S, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M. Multiple facets of intestinal permeability and epithelial handling of dietary antigens. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:247–59. doi: 10.1038/mi.2010.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumann M, Richter JF, Wedell I, Moos V, Zimmermann-Kordmann M, Schneider T, et al. Mechanisms of epithelial translocation of the alpha(2)-gliadin-33mer in coeliac sprue. Gut. 2008;57:747–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.136366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyerlein A, Chmiel R, Hummel S, Winkler C, Bonifacio E, Ziegler AG. Timing of gluten introduction and islet autoimmunity in young children: updated results from the BABYDIET study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:e194–5. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knip M, Akerblom HK, Becker D, Dosch HM, Dupre J, Fraser W, et al. Hydrolyzed infant formula and early beta-cell autoimmunity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:2279–87. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack DR, Ahrne S, Hyde L, Wei S, Hollingsworth MA. Extracellular MUC3 mucin secretion follows adherence of Lactobacillus strains to intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Gut. 2003;52:827–33. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linden SK, Sutton P, Karlsson NG, Korolik V, McGuckin MA. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1:183–97. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuckin MA, Linden SK, Sutton P, Florin TH. Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:265–78. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buffie CG, Pamer EG. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:790–801. doi: 10.1038/nri3535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, Chu H, Karlsson-Sjoberg J, Amir E, et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nature immunology. 2010;11:76–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann ER, Landy JD, Bernardo D, Peake ST, Hart AL, Al-Hassi HO, et al. Intestinal dendritic cells: their role in intestinal inflammation, manipulation by the gut microbiota and differences between mice and men. Immunol Lett. 2013;150:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nutsch KM, Hsieh CS. T cell tolerance and immunity to commensal bacteria. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:385–91. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mortha A, Chudnovskiy A, Hashimoto D, Bogunovic M, Spencer SP, Belkaid Y, et al. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343:1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallis RH, Wang K, Marandi L, Hsieh E, Ning T, Chao GY, et al. Type 1 diabetes in the BB rat: a polygenic disease. Diabetes. 2009;58:1007–17. doi: 10.2337/db08-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thayer TC, Wilson SB, Mathews CE. Use of nonobese diabetic mice to understand human type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39:541–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaarala O. Leaking gut in type 1 diabetes. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2008;24:701–6. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32830e6d98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neu J, Reverte CM, Mackey AD, Liboni K, Tuhacek-Tenace LM, Hatch M, et al. Changes in intestinal morphology and permeability in the biobreeding rat before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2005;40:589–95. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000159636.19346.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee AS, Gibson DL, Zhang Y, Sham HP, Vallance BA, Dutz JP. Gut barrier disruption by an enteric bacterial pathogen accelerates insulitis in NOD mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53:741–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roep BO, Atkinson M, von Herrath M. Satisfaction (not) guaranteed: reevaluating the use of animal models of type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:989–97. doi: 10.1038/nri1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brehm MA, Powers AC, Shultz LD, Greiner DL. Advancing animal models of human type 1 diabetes by engraftment of functional human tissues in immunodeficient mice. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a007757. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teshima CW, Dieleman LA, Meddings JB. Abnormal intestinal permeability in Crohn’s disease pathogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1258:159–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mooradian AD, Morley JE, Levine AS, Prigge WF, Gebhard RL. Abnormal intestinal permeability to sugars in diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1986;29:221–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00454879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arrieta MC, Bistritz L, Meddings JB. Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut. 2006;55:1512–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Groschwitz KR, Hogan SP. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.038. quiz 1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meddings JB, Jarand J, Urbanski SJ, Hardin J, Gall DG. Increased gastrointestinal permeability is an early lesion in the spontaneously diabetic BB rat. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G951–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valladares R, Sankar D, Li N, Williams E, Lai KK, Abdelgeliel AS, et al. Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2 mitigates the development of type 1 diabetes in BB-DP rats. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10507. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Visser JT, Lammers K, Hoogendijk A, Boer MW, Brugman S, Beijer-Liefers S, et al. Restoration of impaired intestinal barrier function by the hydrolysed casein diet contributes to the prevention of type 1 diabetes in the diabetes-prone BioBreeding rat. Diabetologia. 2010;53:2621–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1903-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W, Uzzau S, Goldblum SE, Fasano A. Human zonulin, a potential modulator of intestinal tight junctions. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 24):4435–40. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.24.4435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watts T, Berti I, Sapone A, Gerarduzzi T, Not T, Zielke R, et al. Role of the intestinal tight junction modulator zonulin in the pathogenesis of type I diabetes in BB diabetic-prone rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2916–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500178102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tripathi A, Lammers KM, Goldblum S, Shea-Donohue T, Netzel-Arnett S, Buzza MS, et al. Identification of human zonulin, a physiological modulator of tight junctions, as prehaptoglobin-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16799–804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906773106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fasano A. Physiological, pathological, and therapeutic implications of zonulin-mediated intestinal barrier modulation: living life on the edge of the wall. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1243–52. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fasano A, Not T, Wang W, Uzzau S, Berti I, Tommasini A, et al. Zonulin, a newly discovered modulator of intestinal permeability, and its expression in coeliac disease. Lancet. 2000;355:1518–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02169-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter PB, Collins FM. The route of enteric infection in normal mice. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1974;139:1189–203. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turley SJ, Lee JW, Dutton-Swain N, Mathis D, Benoist C. Endocrine self and gut non-self intersect in the pancreatic lymph nodes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:17729–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509006102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Courtois P, Nsimba G, Jijakli H, Sener A, Scott FW, Malaisse WJ. Gut permeability and intestinal mucins, invertase, and peroxidase in control and diabetes-prone BB rats fed either a protective or a diabetogenic diet. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:266–75. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-1594-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patrick C, Wang GS, Lefebvre DE, Crookshank JA, Sonier B, Eberhard C, et al. Promotion of autoimmune diabetes by cereal diet in the presence or absence of microbes associated with gut immune activation, regulatory imbalance, and altered cathelicidin antimicrobial Peptide. Diabetes. 2013;62:2036–47. doi: 10.2337/db12-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alam C, Valkonen S, Palagani V, Jalava J, Eerola E, Hanninen A. Inflammatory tendencies and overproduction of IL-17 in the colon of young NOD mice are counteracted with diet change. Diabetes. 2010;59:2237–46. doi: 10.2337/db10-0147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mariadason JM, Barkla DH, Gibson PR. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on paracellular permeability in Caco-2 intestinal epithelium model. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G705–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li N, Hatch M, Wasserfall CH, Douglas-Escobar M, Atkinson MA, Schatz DA, et al. Butyrate and type 1 diabetes mellitus: can we fix the intestinal leak? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:414–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181dd913a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Z, Yin J, Zhang J, Ward RE, Martin RJ, Lefevre M, et al. Butyrate improves insulin sensitivity and increases energy expenditure in mice. Diabetes. 2009;58:1509–17. doi: 10.2337/db08-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eckmann L. Defence molecules in intestinal innate immunity against bacterial infections. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:147–51. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000153311.97832.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holmen Larsson JM, Thomsson KA, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Karlsson H, Hansson GC. Studies of mucus in mouse stomach, small intestine, and colon. III. Gastrointestinal Muc5ac and Muc2 mucin O-glycan patterns reveal a regiospecific distribution. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2013;305:G357–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00048.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim YS, Ho SB. Intestinal goblet cells and mucins in health and disease: recent insights and progress. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:319–30. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0131-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fueger PT, Schisler JC, Lu D, Babu DA, Mirmira RG, Newgard CB, et al. Trefoil factor 3 stimulates human and rodent pancreatic islet beta-cell replication with retention of function. Molecular endocrinology. 2008;22:1251–9. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orime K, Shirakawa J, Togashi Y, Tajima K, Inoue H, Ito Y, et al. Trefoil factor 2 promotes cell proliferation in pancreatic beta-cells through CXCR-4-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Endocrinology. 2013;154:54–64. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cunliffe RN. Alpha-defensins in the gastrointestinal tract. Mol Immunol. 2003;40:463–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(03)00157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kaiser V, Diamond G. Expression of mammalian defensin genes. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68:779–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cunliffe RN, Mahida YR. Expression and regulation of antimicrobial peptides in the gastrointestinal tract. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:49–58. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0503249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Wilson CL, Parks WC, Selsted ME, Ouellette AJ. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:113–8. doi: 10.1038/77783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ramasundara M, Leach ST, Lemberg DA, Day AS. Defensins and inflammation: the role of defensins in inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2009;24:202–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nemeth BC, Varkonyi T, Somogyvari F, Lengyel C, Fehertemplomi K, Nyiraty S, et al. Relevance of alpha-defensins (HNP1-3) and defensin beta-1 in diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9128–37. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Iimura M, Gallo RL, Hase K, Miyamoto Y, Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF. Cathelicidin mediates innate intestinal defense against colonization with epithelial adherent bacterial pathogens. J Immunol. 2005;174:4901–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kulkarni NN, Yi Z, Huehnken C, Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH. Phenylbutyrate induces cathelicidin expression via the vitamin D receptor: Linkage to inflammatory and growth factor cytokines pathways. Mol Immunol. 2014;63:530–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chow JY, Li ZJ, Wu WK, Cho CH. Cathelicidin a potential therapeutic peptide for gastrointestinal inflammation and cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2731–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i18.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Courtois P, Jurysta C, Sener A, Scott FW, Malaisse WJ. Quantitative and qualitative alterations of intestinal mucins in BioBreeding rats. Int J Mol Med. 2005;15:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown CT, Davis-Richardson AG, Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, et al. Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25792. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Savilahti E, Ormala T, Saukkonen T, Sandini-Pohjavuori U, Kantele JM, Arato A, et al. Jejuna of patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) show signs of immune activation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116:70–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hänninen A, Jaakkola I, Jalkanen S. Mucosal addressin is required for the development of diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:6018–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Paronen J, Klemetti P, Kantele J, Savilahti E, Perheentupa J, Akerblom H, et al. Glutamate decarboxylase-reactive peripheral blood lymphocytes from patients with IDDM express gut-specific homing receptor alpha4beta7-integrin. Diabetes. 1997;46:583–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jaakkola I, Jalkanen S, Hanninen A. Diabetogenic T cells are primed both in pancreatic and gut-associated lymph nodes in NOD mice. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:3255–64. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Konrad A, Cong Y, Duck W, Borlaza R, Elson C. Tight mucosal compartmentation of the murine immune response to antigens of the enteric microbiota. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:2050–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Natividad JM, Huang X, Slack E, Jury J, Sanz Y, David C, et al. Host responses to intestinal microbial antigens in gluten-sensitive mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCracken V, Lorenz R. The gastrointestinal ecosystem: a precarious alliance among epithelium, immunity and microbiota. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:1–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Locke NR, Stankovic S, Funda DP, Harrison LC. TCR gamma delta intraepithelial lymphocytes are required for self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2006;176:6553–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Todd DJ, Forsberg EM, Greiner DL, Mordes JP, Rossini AA, Bortell R. Deficiencies in gut NK cell number and function precede diabetes onset in BB rats. J Immunol. 2004;172:5356–62. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Alam C, Bittoun E, Bhagwat D, Valkonen S, Saari A, Jaakkola U, et al. Effects of a germ-free environment on gut immune regulation and diabetes progression in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Diabetologia. 2011;54:1398–406. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Badami E, Sorini C, Coccia M, Usuelli V, Molteni L, Bolla AM, et al. Defective differentiation of regulatory FoxP3+ T cells by small-intestinal dendritic cells in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2120–4. doi: 10.2337/db10-1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ejsing-Duun M, Josephsen J, Aasted B, Buschard K, Hansen AK. Dietary gluten reduces the number of intestinal regulatory T cells in mice. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:553–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Flohe SB, Wasmuth HE, Kerad JB, Beales PE, Pozzilli P, Elliott RB, et al. A wheat-based, diabetes-promoting diet induces a Th1-type cytokine bias in the gut of NOD mice. Cytokine. 2003;21:149–54. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(02)00486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Honkanen J, Nieminen JK, Gao R, Luopajarvi K, Salo HM, Ilonen J, et al. IL-17 immunity in human type 1 diabetes. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:1959–67. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lau K, Benitez P, Ardissone A, Wilson TD, Collins EL, Lorca G, et al. Inhibition of type 1 diabetes correlated to a Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2-mediated Th17 bias. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:3538–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dunne JL, Triplett EW, Gevers D, Xavier R, Insel R, Danska J, et al. The intestinal microbiome in type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;177:30–7. doi: 10.1111/cei.12321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bekkering P, Jafri I, van Overveld FJ, Rijkers GT. The intricate association between gut microbiota and development of type 1, type 2 and type 3 diabetes. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9:1031–41. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2013.848793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vaarala O. Human intestinal microbiota and type 1 diabetes. Current diabetes reports. 2013;13:601–7. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0409-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zipris D. The interplay between the gut microbiota and the immune system in the mechanism of type 1 diabetes. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. 2013;20:265–70. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283628569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hara N, Alkanani AK, Ir D, Robertson CE, Wagner BD, Frank DN, et al. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes. Clin Immunol. 2012;146:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Atkinson MA, Chervonsky A. Does the gut microbiota have a role in type 1 diabetes? Early evidence from humans and animal models of the disease. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2868–77. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2672-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science. 2013;339:1084–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1233521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Brugman S, Klatter FA, Visser JT, Wildeboer-Veloo AC, Harmsen HJ, Rozing J, et al. Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the Bio-Breeding diabetes-prone rat. Is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia. 2006;49:2105–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hansen CH, Krych L, Nielsen DS, Vogensen FK, Hansen LH, Sorensen SJ, et al. Early life treatment with vancomycin propagates Akkermansia muciniphila and reduces diabetes incidence in the NOD mouse. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2285–94. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2564-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sofi MH, Gudi RR, Karumuthil-Melethil S, Perez N, Johnson BM, Vasu C. pH of drinking water influences the composition of gut microbiome and type 1 diabetes incidence. Diabetes. 2013 doi: 10.2337/db13-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Suzuki T. Immune-Deficient Animals in Biomedical Research. 1987:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 92.King C, Sarvetnick N. The incidence of type-1 diabetes in NOD mice is modulated by restricted flora not germ-free conditions. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Murri M, Leiva I, Gomez-Zumaquero JM, Tinahones FJ, Cardona F, Soriguer F, et al. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: a case-control study. BMC medicine. 2013;11:46. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mejia-Leon ME, Petrosino JF, Ajami NJ, Dominguez-Bello MG, de la Barca AM. Fecal microbiota imbalance in Mexican children with type 1 diabetes. Scientific reports. 2014;4:3814. doi: 10.1038/srep03814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Endesfelder D, zu Castell W, Ardissone A, Davis-Richardson AG, Achenbach P, Hagen M, et al. Compromised gut microbiota networks in children with anti-islet cell autoimmunity. Diabetes. 2014;63:2006–14. doi: 10.2337/db13-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kemppainen KM, Ardissone AN, Davis-Richardson AG, Fagen JR, Gano KA, Leon-Novelo LG, et al. Early childhood gut microbiomes show strong geographic differences among subjects at high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:329–32. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Novelo LL, Casella G, et al. Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. The ISME journal. 2011;5:82–91. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kriegel MA, Sefik E, Hill JA, Wu HJ, Benoist C, Mathis D. Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108924108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van den Brandt J, Fischer HJ, Walter L, Hunig T, Kloting I, Reichardt HM. Type 1 diabetes in BioBreeding rats is critically linked to an imbalance between Th17 and regulatory T cells and an altered TCR repertoire. Journal of immunology. 2010;185:2285–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bradshaw EM, Raddassi K, Elyaman W, Orban T, Gottlieb PA, Kent SC, et al. Monocytes from patients with type 1 diabetes spontaneously secrete proinflammatory cytokines inducing Th17 cells. Journal of immunology. 2009;183:4432–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ferraro A, Socci C, Stabilini A, Valle A, Monti P, Piemonti L, et al. Expansion of Th17 cells and functional defects in T regulatory cells are key features of the pancreatic lymph nodes in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60:2903–13. doi: 10.2337/db11-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yin Y, Wang Y, Zhu L, Liu W, Liao N, Jiang M, et al. Comparative analysis of the distribution of segmented filamentous bacteria in humans, mice and chickens. ISME J. 2013;7:615–21. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schwartz RF, Neu J, Schatz D, Atkinson MA, Wasserfall C. Comment on: Brugman S et al. (2006) Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the Bio-Breeding diabetes-prone rat. Is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia 49:2105–2108. Diabetologia. 2007;50:220–1. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0526-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hageman I, Buschard K. Antidiabetogenic effect of fusidic acid in diabetes prone BB rats: a sex-dependent organ accumulation of the drug is seen. Pharmacology & toxicology. 2002;91:123–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Carlstedt-Duke B, Hoverstad T, Lingaas E, Norin KE, Saxerholt H, Steinbakk M, et al. Influence of antibiotics on intestinal mucin in healthy subjects. European journal of clinical microbiology. 1986;5:634–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02013287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Calcinaro F, Dionisi S, Marinaro M, Candeloro P, Bonato V, Marzotti S, et al. Oral probiotic administration induces interleukin-10 production and prevents spontaneous autoimmune diabetes in the non-obese diabetic mouse. Diabetologia. 2005;48:1565–75. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Caballero-Franco C, Keller K, De Simone C, Chadee K. The VSL#3 probiotic formula induces mucin gene expression and secretion in colonic epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G315–22. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00265.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Schlee M, Harder J, Koten B, Stange EF, Wehkamp J, Fellermann K. Probiotic lactobacilli and VSL#3 induce enterocyte beta-defensin 2. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:528–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wolf KJ, Daft JG, Tanner SM, Hartmann R, Khafipour E, Lorenz RG. Consumption of Acidic Water Alters the Gut Microbiome and Decreases the Risk of Diabetes in NOD Mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62:237–50. doi: 10.1369/0022155413519650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Claudino M, Gennaro G, Cestari TM, Spadella CT, Garlet GP, Assis GF. Spontaneous periodontitis development in diabetic rats involves an unrestricted expression of inflammatory cytokines and tissue destructive factors in the absence of major changes in commensal oral microbiota. Experimental diabetes research. 2012;2012:356841. doi: 10.1155/2012/356841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bakirtzi K, Hoffman JM, Pothoulakis C. Silence Please!: siRNA approaches to tighten the intestinal barrier in vivo. Am J Pathol. 2013;183:1700–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]